The Most Memorable Year: Highlights of 2020

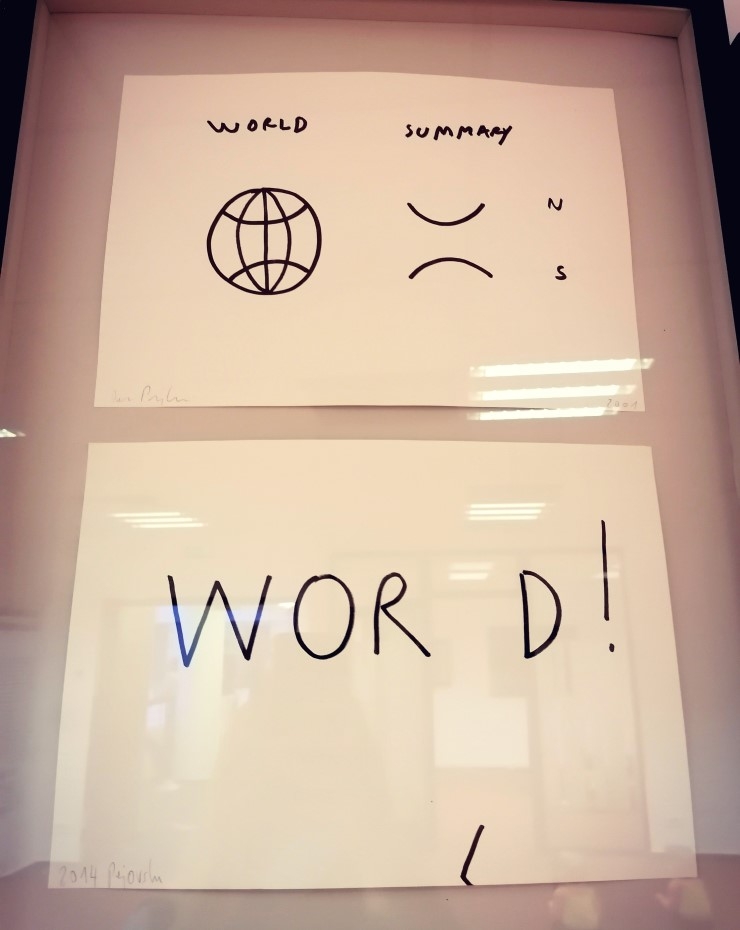

Piotr Sikora | Czechia

Instead of writing a typical 2020 summary I’ve taken it upon myself to write a letter to Santa Claus. For the record, Santa isn’t anymore this boring boomer consumer daddy dressed in red but a glam drag superstar vegan wearing nothing but a second-hand pink robe and fighting for climate neutrality – GO SANTA!

Dear Santa,

I’m writing to you feeling like I’m a little boy again, an angry little fellow filled with anxiety and tension that boil within oneself right before erupting into long and annoying puberty.

But where are my manners! I hope you’re doing great Santa, fighting for the cause, smashing the patriarchy and queering Xmas. Not to mention you’re such a great performer – at least as inspiring as the House of Garbage in Plastics, true glamour, chapeau bas! Having said that, I’d like to kick off with my first wish – please let the daddies from the Czech Visual Art Academy (Česká akademie vizuálního umění) find their true destiny and become the next drag superstars! So much potential is being wasted on prizing the obsolete concepts of art awards – thanks Absolute! they are fading away – and bringing to life yet another boys club. Once they become true emancipated queens – please Santa, please! – make them join the Feminist Institution collective, yes the same one which was applying for the director’s position at the National Gallery and eventually have became a collective member of the advisory board of the NGP. Speaking of the NGP – here comes my next request – make Alicja Knast the greatest directress of the biggest Prague-based institution. Please allow her to turn this dubious place into a cozy home-like place and a blast of a gallery providing more shows such as the Kurt Gebauer retrospective and less gestures such as getting rid of all records of Adam Budak’s unforgettable Moving Image Department (shame on you NGP!).

There is plenty of work to be done and I’d be silly to think it can be solved without the special forces of your top quality helping goblins which are currently engaged with Plato Ostrava.

Santa, could you add to the Czech vocabulary a new idiom, an embarrassment of riches? It would be very helpful in describing the supersized support coming from the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Labour into the art scene this year. It’s unavoidable to say that the way the surplus of money was distributed was wrong – focusing rather on the support for institutions and neglecting help for the actual cultural producers – artists, art professionals – who were left in the lurch. Still, all of the bigger, smaller, and medium places that animate culture in the Czech Republic were able to apply and got support – counted in millions of korunas – not to mention the ministry is announcing more and more support. The question is for how long will the embarrassment of riches last?

Santa, bring me some of the most exciting books published last year: Milk and Honey by Kateřina Olivová, allow me to try some of the water from the moon, make Dolly Parton make a farewell anthem for corona and cancel once and for all ‘-ova’ from Czech female names.

OK here comes the last one – Santa, I know I’m asking for a lot but is there a slight chance to make the Ciocia Czesia initiative, supporting the Polish womens’ protest, grow as big as the heretic hussites did in the 1400s and plunder into the Polish territory, getting once and for all rid of the rotten clergy and kidnapping members of the ruling party. YES I demand abortion of the Polish goverment now!

And last but not least, Santa, please save us from more: webinars and zoom conferences, take away dinners, stupid right-wing conservative goverments and their patriarchal structures, pointless podcasts, beers in plastic cups and online exhibitions! Make this world more queer and more livable than in 2020 please.

Your always and forever Piotr a.k.a Miss Summer

***

Oleksiy Radynski | Ukraine

The editors of BLOK have asked me to name this year’s highlights ‘without grumbling’, focusing instead on ‘only the best stuff’ that happened in 2020. While the tendency for positive thinking at the end of this disastrous year is understandable, I must admit a total impossibility to follow the editors’ guidelines. It would be utterly irresponsible to seek for any glimmer of hope in a situation when the global pandemic has in fact offered a mere excuse, a logical rationale to foster the tendencies that were already destroying Ukrainian art before 2020 hit.

Well before we were told to go into lockdown, art spaces – independent and commercial alike – were already shutting down at increasing pace, forced out by the not-so-invisible hand of the market. Well before we’ve first heard of social distancing, this notion had in fact been practiced in the exhibition halls of numerous art institutions whose audience had become so scarce that the virus would simply not be able to spread in their premises. And well before self-isolation became a norm, the collectivist spirit of a previous decade had already given way to a profound atomization, polarization and dissolution of art communities. 2020 was, then, not so much a disruption of artistic life, but a rather fitting summary for a decade full of extraordinary enthusiasm, dreams and delusions that gradually gave way to depression and degradation. If there’s any potential for hope still, it should come in the form of a decisive break from the delusions that have defined the artistic processes of the last decade.

I’m therefore submitting my humble summary of 2020 in Ukrainian art under the well-known motto ‘the worse the better’. Each of the grotesque events outlined below are important not because they are so outrageous, but because they’re all helpful in dispelling the misconceptions that’s been stifling artistic life for some time now. The sooner this happens, the sooner the new beginning will become possible.

I.

The PinchukArtCentre fired its entire department of guides in an act of collective punishment for their attempt at unionizing. This happened shortly before the opening of the Pinchuk Prize exhibition featuring, as usual, a number of ‘notoriously leftist’ young Ukrainian artists (two of them withdrew their works from the exhibition).

This event marks the perfect ending to a long period in Ukrainian art defined by an illusion that collaboration with authoritarian, oligarchic institutions is still able to open up new possibilities for debate and social transformation. Instead, contemporary art has become a perfect tool in persuading that black is white, truth is lies, capitalism is democracy, and so on. It’s hard to imagine a more devastating satire of this state of affairs than a bunch of art students getting fired for their demand of a slightly less precarious position in their job of explaining leftist artworks to the audience of an oligarch-led institution.

To make things worse, the curators of PinchukArtCentre launched a public attack against the fired guides, presenting their institution as a vulnerable victim of a well-coordinated attack by the media and the all-powerful unions (all this in a country where unions have no real influence whatsoever, as they are widely seen as redundant relics of ‘socialism’, while the influence of oligarchs like Pinchuk himself is immense). The good news: even a powerful institution like this can be thrown into a profound crisis by a couple of media-savvy art students.

II.

The Malevich Prize had no women artists on its short list for a second year in a row. This time, the choice has finally caused the organizers some trouble, with the male finalists publicly chastising the selection committee for their gender-insensitive decisions.

The irony of the situation: this prize had been established by the Polish Institute as part of a far-reaching endeavor by the Poles to spread the ‘Western values’ in a backward Ukrainian society. In the meantime, a curious reversal had occurred: Poland itself has descended into a nightmare of the new Dark Ages, epitomized in this year’s court ruling that forces Polish women to give birth to defective fetuses. The increased sensitivity around the Malevich Prize is also due to the fact that its jury now includes the neo-fascist Piotr Bernatowicz, a new director of the CSW Zamek Ujazdowski (the institution that originally co-founded the prize).

Ukrainian artists have been long taught to look up to ‘Western’ art institutions as beacons of professionalism and perfection. The crisis of the Malevich Prize and the downfall of numerous Polish art institutions are an ultimate reminder that the quality of institutions is not defined by their geographical position or the scale of their funding. It is defined by their politics.

III.

The debate around the Babyn Yar Memorial in Kyiv has been reduced to a social media shitstorm of epic proportions, with no positive solution in sight. The situation was triggered by the appointment of Ilya Khrzhanovsky, a Russian experimental filmmaker and the author of the infamous DAU project, as the artistic director of a memorial that’s currently planned by the private investors from Ukraine, Russia, and Israel. For the eight decades that have passed since the mass shooting of hundreds of thousands of Jews and other minorities in Kyiv’s Babyn Yar, the place has seen almost no signs of commemoration – barring a small number of kitschy and makeshift monuments that have proliferated in recent years.

The arrival of Ilya Khrzhanovsky, with his grotesque ideas (most of them became known from a leaked memorial concept that its author claims to be merely an early draft), created a perfect storm in an already polarized and inflamed society. An unbelievable coalition of pro-Western liberals, conservative Jewish organizations, anti-semitic nationalists and outright neo-Nazis had united in a campaign demanding Khrzhanovsky’s resignation, and an end to the project of a private memorial. The real problem with this campaign, however, is that it actually helps Khrzhanovsky’s project get more legitimacy and credibility while discrediting his critics as hysterical xenophobes.

It’s true that the memorial project itself should be questioned from top to bottom, both in terms of its politics and aesthetics. Its funding sources and decision making processes are extremely obscure, and Khrzanovsky’s ideas of ‘immersive performance’ on the subject of mass shootings and the use of private visitor data to ‘personalize’ the exhibition experience are utterly insensitive, at best. Still, as long as the project’s loudest critics are most concerned with the issues regarding Khrzanovsky’s citizenship and nationality, this kind of ‘public debate’ serves as a perfect spoiler that distracts attention from what’s actually most problematic in this project.

As a result, no one even remembers that the whole memorial project was launched by none other than Kyiv’s notorious mayor, Vitaliy Klichko, who makes no secret of his plans to ultimately transform the city into a concrete jungle covered with gated housing estates. In the meantime, Babyn Yar and the vast green area adjacent to it is one of Kyiv’s last frontiers, still untouched by commercial construction. In the eyes of this city government, the emergence of an ‘innovative’ memorial is nothing but a pretext to finally cover this difficult area with housing towers, with some of them already under construction. Contemporary art has been instrumental in gentrifying all kinds of places on Earth, but Babyn Yar is en route to becoming the most exotic of those, by far.

Is there another lesson to be learned from this bitter story? Yes. As long as our crucial public debates take place on a ‘platform’ provided by Facebook, Inc., they will all sooner or later descend into shitstorms, trolling and shaming – simply because this is what this platform is actually designed for. A mass exodus is urgently needed.

***

Gergely Nagy | Hungary

Where is the state?

Culture, art and politics in 2020 in Hungary

Needless to say that in Hungary, like in lots of other countries elsewhere, almost every major event in the contemporary art scene was cancelled or delayed in 2020. Not everything though, for example, Time-wasting, the oeuvre exhibition of one of the most important contemporary artists, Balázs Kicsiny at Debrecen’s MODEM. The presented works were a set of installations which show the tragic absurdity and a certain ironic heroism of the existence we all know well in this region I guess.

OFF-Biennále Budapest (OFF), the largest independent art event originally scheduled to April and May of 2020 had to be rescheduled to Spring 2021. But despite the hiatus, OFF gained international attention two times in 2020. First when ruangrupa invited OFF as an organization to the team of documenta15, and second when at the end of the year, ArtReview’s Power 100 was revealed with the initiator of OFF, Hajnalka Somogyi on the list.

This is also a signal showing that in Hungary, the cultural field is irrevocably polarized now: we have official and unofficial culture, two different galaxies. The government supported, ideological, and politically loyal art is imperceptible to the rest of the world while the products of the counterculture, or unofficial culture, are very much visible. At the same time the disproportionality is enormous at home: OFF (which does not apply for any public funding in Hungary and stays away from the state-funded art infrastructure) runs on practically no money and does not have a single mention in the so called “public service media”. Just like many other smaller or also bigger art initiatives in Hungary, it exists in a parallel reality, which is closer to the consensual reality of the international art world. There is a whole sphere of arts and culture that is not represented on the level of the institution and remains hidden for the vast majority of the Hungarian people. It’s almost like it was in the times before 1989.

The atmosphere of the early 80’s has sneaked back in many ways during the pandemic: borders closed, armed soldiers patrolling the streets and the government (ie. the party) rules by decree. Unlike in many other European countries, in Hungary, the government did not provide direct aid to the people who lost their income. Orbán’s Hungary is not a welfare society but a “workfare society” as he says, and in a labor-based system it is unacceptable to give anybody money for free. Therefore independent artists, gallerists, art organizers, and arts workers could not get anything. There was some indirect help though things like tax easement and certain businesses got financial aid in order to keep their employees – but it does nothing to help freelancers, does it? In the meantime, the Hungarian National Bank (MNB) started a huge program in order to build up a contemporary art collection and spent at least 4 million euros in the galleries, buying hundreds of art works from some of the biggest names in Hungarian modern and contemporary art. MNB purchased the works through a company established by the bank but today, in this country, it is almost impossible to tell if the money that such a company spends is still public money or something else. A change in the constitution in December redefined the phenomena of public money: “Public money is the revenue, expenditure, and due of the state.” Are the companies and foundations established by state institutions still part of the state?

A certain privatization process is going on in the field of art. In 2020 the government changed the status of every employee in publicly-funded cultural institutions, museums, galleries: they are not public servants anymore and are “put out” on the job market. There is no protection for cultural workers, the state does not take any responsibility.

Privatization went further in higher education as well. Art universities also became subjects of these fundamental changes, which caused the biggest act of resistance in 2020 (and also from, 2010). Students of SZFE (University of Theatre and Film Arts) occupied their university buildings on the 31th of August and locked out the members of the new board of SZFE appointed by the government. The state turned its back on the university, gave it to a foundation led by a board of private persons – all of them 100% loyal to Fidesz, the ruling party. The students kept the building for more than 70 days, organizing and managing the education by themselves, no courses or classes were cancelled, though at some point the new board formally banned (!) education in any form at SZFE. #freeszfe became not only a buzzword but a whole movement, with big demonstrations and large street performances which supported the students who left the buildings only due to the pandemic situation but still keep up the resistance now in virtual space.

They won the battle against the board – at least in the eye of the public. But will they win the legal battles as well? Is there anything left in the ruins of the legal state in Hungary? 2021 will tell.

***

Anna Karpenko | Belarus

When remembering 2020, it is hard to mention anything essential that is not the fundamental shift that began in August 2020 after the so-called presidential elections in Belarus.

There are three main points that I will now focused on:

- Horizontality and community. There was a slogan that appeared in the first days of the peaceful protests: “We hadn’t known each other till that summer”. Faced with the enourmous level of violence and torture from the state, the Belarusian people joined their struggle together in a strategy of small steps. They gathered for local activities in neighbourhood courtyards to drink tea, to play with children, to hold philosophical debates or theater shows. All these simple, everyday activities have been absent for the past 26 years under the regime; people would sit in their kitchens to discuss politics or in most cases, not pay attention to politics at all. But since August 2020 every simple element of life has taken on additional meaning – it has become a part of the political and public sphere. Now, you don’t know if you will make it back home from a trip to the supermarket on Sunday. Because you can easily be detained by masked, unknown people who check your phone.

- Appropriation of the art realm by non-artists. This can probably be seen as one of the most essential characteristics that describes what has happened with the local art scene. On the one hand, when we all went to the streets to participate “every day” in peaceful protests, identification was eliminated in the division between professional and amateur. The creative splash that took place during the peaceful Belarusian protests showed an enormous quantity of objects, slogans, and installations released as artistic statements but not belonging to professional artists. On the other hand, the artistic community joined together only once to make an action behind the doors of the “Palace of Art” in Minsk to show their dissent with the unimaginable tortures and violence that has and is still occurring in detention centers and prison cells within the first days of the protests. Many artists like Nadia Sayapina, Maxim Yasinski, and Helen Hil were detained and spent from 2 to 15 days in these cells.

- “Nothing is there” (Нiчога няма) – is the title of Belarusian artist Alexey Lunev’s 2009 work. It was first shown in 2009, a year before the 4th so-called elections of Lukashenko in Belarus. That was a reaction to and a bright metaphor for the area which we now find ourselves in Belarus. When there was an underdeveloped institutional sphere there were no possibilities for artists to be exhibited, to participate in large international shows, to ask for financial support (there weren’t any non-governmental foundations which supported art). The only place where artistic statements could be free from censorship was the Gallery of Contemporary art Y. In October 2020, the Gallery owner, Aliaksandr Vasilevich, was detained for the second time and a criminal case had been developed against him. He is still in prison for his civil position and is one of 169 officially recognised political prisoners in Belarus. In October 2020 it was announced that Y Gallery ceased its existence.

We are back to the situation of 2009 but will never go back to the life we lived before. We keep going forward on our path to freedom.

To know more about Belarusian protests: https://www.instagram.com/highlightbelarus/

To support Aliaksandr Vasilevich: https://solidaritywithalexander.com

***

Corina Apostol | Estonia

In a year of unpredictability, the Estonian art scene continued to survive and at moments to thrive, enjoying a relatively sheltered position compared to the rest of Europe, with most institutions remaining open for the bulk of the pandemic.

Before the pandemic took hold, the year began on an exciting note: the Estonian exhibition at the 59th Venice Art Biennale (now slated for 2022) will take place in the Rietveld Pavilion in the Giardini, at the invitation of the Mondriaan Fund. While Estonia itself has been exhibiting at the event since 1997, as a “young nation” it cannot build its own pavilion inside. This unexpected switch highlighted how certain countries are excluded from being in the center of the biennale. The winning proposal for Venice, a project curated by the author featuring artist Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi, “Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance” is inspired by botanical artist Emilie Rosalie Saal‘s watercolors and paintings of tropical plants, proposing a multifaceted view of colonial history. Also notably, the symposium “Prisms of Silence,” curated by art historians Margaret Tali and Ieva Astahovska took place at the Estonian Art Academy before the lockdown, convened a variety of international speakers to analyze the silences about WWII, its aftermath and the Soviet era in order to explore how they could offer productive ways of understanding present social change.

Despite the lockdown on cultural life in Estonia last spring, several incredible artists, activists, and thinkers presented art projects that drew attention to some of the most pressing issues in their context. Flo Kasearu’s “State of Emergency” (KUMU) drew attention to museum invigilators’ new daily routines, Jevgeni Zolotko’s “Silent” (Tartu Art Museum) focused on the suppression and existential and political ideas, Britta Benno’s “Ruinenlust Lasnamägi” (Hobusepea gallery) imagined a bizzare, dystopic Tallinn that seems frighteningly present, Ede Raadik’s “The Best You Can Ever Be” (Tallinn Art Hall) looked at violence against women and the politics of care – to mention just a few. Cultural venues ventured more into the digital realm to connect with their audiences. A notable initiative by the Tallinn Art Hall, a virtual platform for exhibitions was developed, building on existing and accessible tools and processes—cinematography, interactivity, and web applications.

The Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia (EKKM), which was threatened with eviction after over 13 years of operating on the grounds of the Tallinn Creative Hub foundation (Kultuurikatel), launched an international campaign of solidarity. After receiving widespread support, the renowned artist-led initiative convinced the Tallinn City Government and Kurtuurikatel to keep operating in the historic premises that are slated for renovation. Tallinn Art Hall also received major support from the Ministry of Culture to renovate its modern functionalist building dating back to 1934.

However, other important artist-run initiatives such as Kraam, an artist-run space and free shop based in Tallinn closed their doors due to heightened gentrification and lack of state or private support. While artists in Estonia were offered crisis relief and support measures to defray the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns, independent cultural producers at times felt the information was quite fragmented and excluded certain categories. The questions of who has access to support and what blind-spots state measures exist became ever more important during the crisis. Recently, the Center for Contemporary Art Estonia, Estonian Artists’ Association, Estonian Contemporary Art Development Center, and activist and art worker Airi Triisberg, have joined forces to offer crisis consultation to better navigate the emergency situation.

***

Anastasia Vepreva | Russia

I will immediately make a reservation that I do not even pretend to conduct an all-encompassing analysis and will rather quickly jump through several points of my memories of this strange year, of which I was lucky enough to become a part of. The importance of which, in my opinion, is enormous and without denial of the contribution of others. The covid year, although it canceled a number of events, nevertheless did not completely paralyze the situation. Underground initiatives, as before, survived against all odds, and now they continue to do so.

The approach to the creation of exhibitions has changed in an interesting way. “Anti-festival of Mutations” (St. Petersburg) curated by the group Chto Delat has assembled a stellar cast of artists, using, among other things, the method of delegated creation of a work, when artists interpreted or repeated (by agreement with the author) in-situ, the work of another artist. HOMECOMING (Arkhangelsk – Curator: Kristina Dryagina), thanks to the online format, was able to acquaint people with the works of northern indigious peoples found in the Arkhangelsk archive – and thus mark a new turn in decolonization.

The new St. Petersburg gallery – Little Blue Wandering Cabin – made a series of solo exhibitions with which the viewer could individually and safely contact by visiting a changing booth that migrated around the city. Also, in spite of everything, two blockbusters managed to open – NEMOSKVA (Manezh, St. Petersburg), which claims (not without scandals) to cover and represent various regional artists, and the Second Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art (Moscow), which put the idea of corruption at the head, inviting the previous participants – the first triennale artists to recommend participants for the second edition – without any curatorial ambitions.

Separately, I would like to note two art groups from St. Petersburg, balancing on the edge between art and music, that have distinguished themself this year. One of them is the fem-punk duo “Krasnye Zori” who released a long-awaited video for the song Zemleroika, while others – the interdisciplinary cooperative “Techno-Poetry” released a new album “The Apocalypse is Unavoidable” as well as several clips. A special event was the launch of mockumentary – a series that talks about the St. Petersburg underground culture using several examples of local bands and their fascinating speculations about their possible future successes.

An interesting work with space, knowledge, and theory was done for the Assembly space by the collective of dance artists Valya Lutsenko, Anya Kravchenko and Marina Shamova – in a series of walks called “What is actually going on?”

Also, several initiatives / events raised issues of precarity, labor solidarity, and burnout of art workers, which have become aggravated during the quarantine period. N I I C H E G O D E L A T, the St. Petersburg group, continued the World Without Labor biennale, which took place simultaneously online and offline, and the League of Tenders convened another retreat-congress on the Black Sea, at the residence of the ZIP art group in Anapa. Also in Moscow, a Fem-dacha was launched for burned-out fem-activists, where they could rest in caring for each other.

Especially, it is worth noting the work of self-organized media that covered the activities of (not only) local communities – for example, the editors of the KRAPIVA journal who were clearly outlining their turn towards decolonization and organized a large performative conference in which the issues of knowledge production and its value for a particular community were raised.

***

Mike Watson | Finland

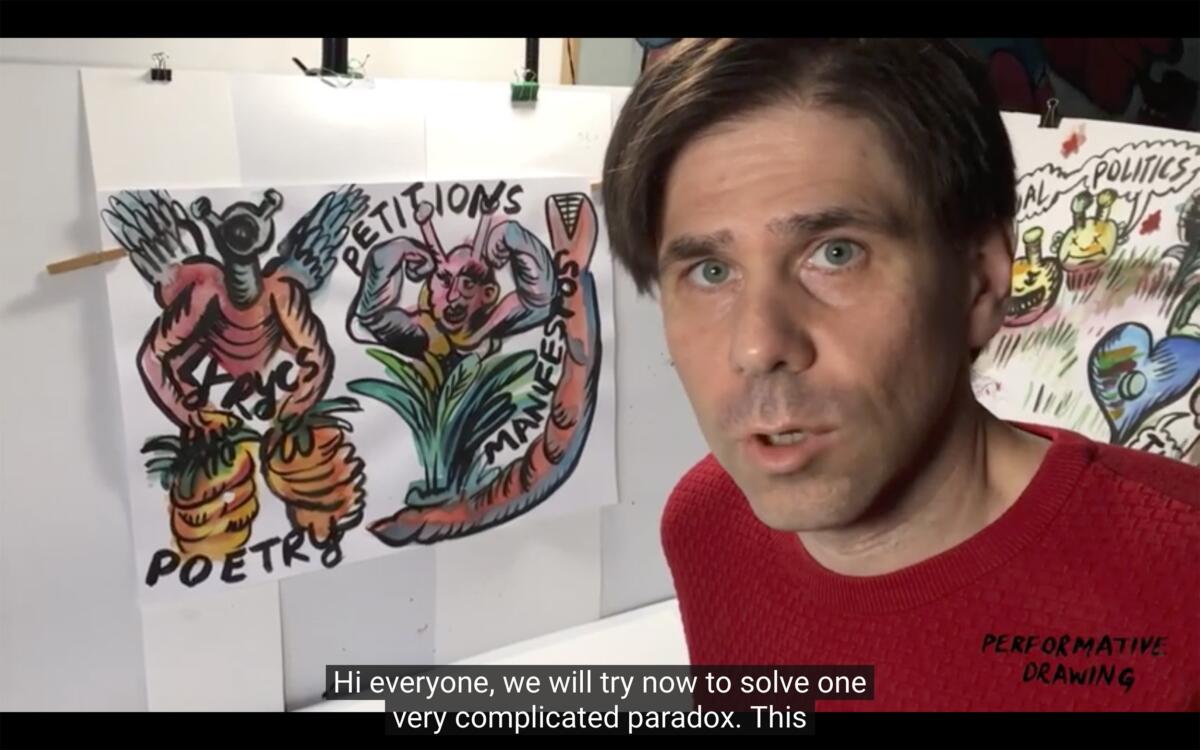

2020 was very nearly the year that wasn’t. Lockdown led to the cancellation of most planned contemporary art events forcing us freelance writers, artists and educators online. For me, the most convincing artist-made online projects have been conceived as 2-D screen based media, rather than seen as a substitute for the ‘in real life’ museum experience. These include Rean Raedle and Vladan Jeremic’s Performative Drawing, a YouTube channel where the multimedia arts duo based in Belgrade produce Bob Ross style painting tuitions with a left-wing message. Camera angles, speech patterns and format all mimic the famous TV painting tutor, while themes range from Ecology to Žižek and Hegel, to Adorno’s Culture Industry. The channel began in May 2020 during lockdown but is a continuation of the artists’ ongoing collaboration around social issues.

Another artist who made the transition to YouTube is Austrian filmmaker Oliver Ressler, whose video installations have for decades been featured in museums, galleries and biennials. Ressler has since July 2020 been uploading his back catalogue to YouTube. While conceived for art spaces, these videos are essentially documentaries and the free online format allows their messages to be seen potentially by anyone. Videos such as The Visible and the Invisible and Leave it in the Ground will allow a wide audience to benefit from Ressler’s exposure of the exploitation of natural resources for capitalist gain.

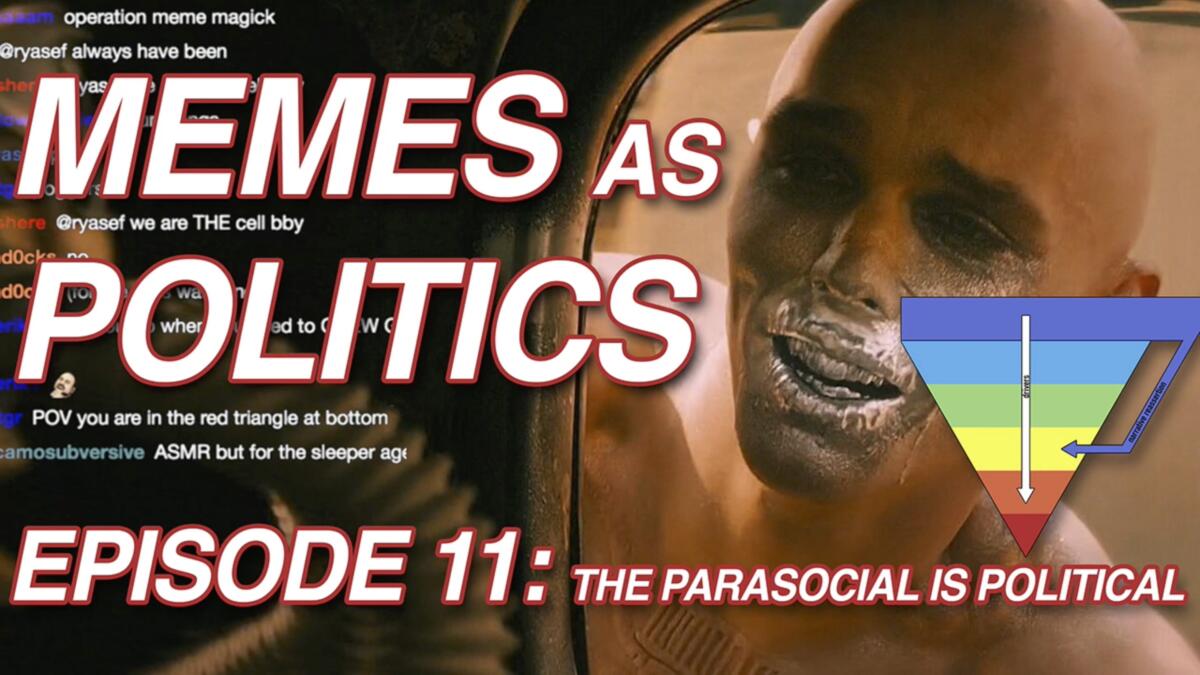

Finally, Joshua Citarella, artist, twitch streamer and Instagrammer is a latecomer this year to YouTube, having set up his account in December. Citarella is a US artist who has grown as much online as in art spaces, taking to twitch to analyse memes, contemporary art and left-wing YouTube videos. Usually ahead of the game, his YouTube account promises to be a hub for the crossover between the realms of art and meme-making in 2021 — a year in which we hope to see a return to business as usual in the arts, as much as a deepening of the quality of online contemporary art initiatives.

***

Ivana Rumanova | Slovakia

In 2020:

- At the end of October, due to the anti-pandemic measures, the Slovakian government enforced a curfew, with the exception of the somehow absurd interval between 1 a.m. – 5 a.m. To express support with the „To jest wojna” movement, the anonymous citizens of Bratislava used this interval to cover the Polish institute with banners, posters and candles. These were taken down in the morning of course by the employees of the Polish institute but new signs of support appeared the following nights. This subversive „processual exhibition“ was for me a great example of how to take the current limitations of what can be done in public space into play. All the more so as the „politically and socially engaged“ art and cultural institutions, situated on the very same square, remained silent.

- APART collective opened a new venue in the Petrzalka neighborhood which proclaims itself to be openly antifascist and feminist. It is situated in the civic-amenities part of a block of flats (former stock), and a huge common terrace provides access to it. The terrace is a remnant of the modernist concept of „vertical cities“ in which different activities were supposed to be taking place on different city-levels. Terraces connecting the block of flats were intended to create a zone of meetings and interactions for pedestrians and random passers-by. For an artist-run space the terrace is not only a great spot for a cigarette and a small talk, but this direct situatedness in a „vertical city“ could be a permanent reminder of its own complicity in gentrification. The first show „Gaming the Aftermath“ curated by Diffractions Collective and APART opened on 11 December.

- Anetta Mona Chişa and Lucia Tkacova installed a statue representing Karl Marx’s large intestine (The Gut, 2020) in Chemnitz that is proportional to his huge bust (7,1 m), the largest one in the world occupying a representational spot in the very same city. It is hard to imagine a more „Marxist“ commentary to the fact that public space is being occupied by the authoritative heads: The microbiome monument represents the work of milliards of anonymous organisms; instead of rationality, it points out the function of the involuntary muscles that are beyond our control, it spreads out horizontally in the park without any platform, serving as a bench or children’s playground. Marx’s head thus finally got its dialectic complement.

- Spolocnost Jaromira Krejcara was founded with the aim to save the Machnac sanatorium (Jaromir Krejcar, 1932), one of the greatest examples of functionalist architecture in Central Europe. Despite the fact that it was proclaimed a national cultural monument in 1995, the building has been passed from one shell company to another which has left it in a state of a ruin. One of the considered strategies of the Spolocnost Jaromira Krejcara to protect Machnac is its expropriation, which would create an important precedent in the Slovak context.

- It might sound like a cliché, but the current pandemic crises have re-opened the hibernating debates on solidarity platforms for precarious workers in arts and culture. As such it does not guarantee anything, but there’s already a shift producing, among other things, the notion that terms such as „trade unions“ slowly stop being perceived as archaic or vulgar.

***

Julius Pristauz | Austria

That this year was not the one for anybody at all seems to be somewhat clear. However turbulent it might have been for all kinds of cultural spaces, from museums to independently run places, it appears that local galleries and fairs struggled specifically. Fighting financial uncertainty, restrictions, and repeated sudden closures as well as some internal problems within the association of Austrian commercial galleries in general, one can only hope for a little more harmony and a stronger sense of community in 2021. Nonetheless, in the manner of “always looking on the bright side of life”, you can find below a short, subjective, chronological summary of a few highlights from the bumpy ride that was this past year in the Austrian art scene.

Nicole Gravier’s Photoromans: Mythes & Clichés at Ermes Ermes in Vienna left a lasting impression. In this series of collages on photographs (all produced between 1976-1980), the artist beautifully criticizes prevailing concepts of femininity and domesticity. Making use of the narrative structures of a photo novel, Gravier asks subversive yet definite questions about gendered dynamics, especially exciting if one considers that these series have their roots in Italy of the late seventies, shortly after a law on divorce was passed and right when one for abortion was first agreed on.

The Kunsthaus Bregenz (KUB) continued their bright picks of relatively young artists for another year: Following an impressive showcase of Raphaela Vogel’s extensive sculptural multimedia installations, the first exhibition of the year at KUB was conceived by similarly young and ambitious American artist Bunny Rogers. In her exhibition Kind Kingdom, the artist staged macabre scenes dealing with the mediated immediacy of death as well as with public forms of mourning. Unknowing of what lay ahead, this show truly hit the mark.

Currently on view and therefore closing the year for KUB is another great choice, artists Jakob Lena Knebl and Ashley Hans Scheirl. The shooting star couple will also realize Austria’s contribution to the postponed Biennale D’Arte Di Venezia 2022. A promising show as well as a pavilion to look forward to.

Non-performative diversity and sufficient discussions surrounding structural and intersectional critique are still lacking within the Austrian scene, especially at an institutional level. However, we would also like to be hopeful in that regard. With the collective WHW taking over the role as directors of the Kunsthalle in Vienna, the scene is to expect more political art and some opposing positions to a previously very commercially-coined canon. The collective’s first exhibition … of bread, wine, cars, security and peace which also served as a kind of mission statement at times could feel crammed and slightly chaotic. Still, navigating one’s way through this extensive show was equally rewarding and refreshing as it was challenging. Clearly focusing on content rather than aesthetic decisions, a few pieces stood out in particular, making up for some less reasonable decisions in regards to display and position within the space. Spatially separated from the rest of the exhibition, the must-see immersive video installation Mission Accomplished: Belanciege by Giorgi Gago Gagoshidze, Hito Steyerl & Miloš Trakilović playfully compares tendencies and mechanisms of the emancipation of an image, found in both fashion and politics. Other highlights in the show included drawings of de- and reconstructed bodies by Selma Selman as well as the presentation of almost forgotten works by Austrian avant-garde artist Anne Marie Jehle.

While artist Melanie Ebenhoch also presented work in the inaugural exhibition at the Kunsthalle, she simultaneously opened her first solo exhibition at gallery Martin Janda which offered a more precise insight into the painter’s practice. Making use of references that are closely tied to the history of film, Ebenhoch takes a critical turn on these influences by means of adopting some of them within her own motives, composition, and particular choice of colours.

As the year progressed and many events faced various restrictions and endless hours of reconsidering and rescheduling have been spent, to the point where great spontaneity and a willingness to work against the odds were needed.

Quite fittingly, during Vienna’s gallery festival CuratedBy, the exhibition AS TIME WENT ON, A RUMOUR STARTED at Gianni Manhattan challenged some prevalent (mis-)conceptions about the structure and organization of time and our distorted perceptions of such during this pandemic. In addition to pieces by Mire Lee and Guillaume Maraud, artist and curator James Lewis got his audience chattering by further including an unauthorized contribution in the form of a YouTube video of electronic music superstar Aphex Twin. Serving as a good reminder that sometimes less is indeed more, the three pieces in this exhibition all looked at continuity, rhythm and repetition in their own right, proposing different readings of the relation of time and space in a currently exceptional state.

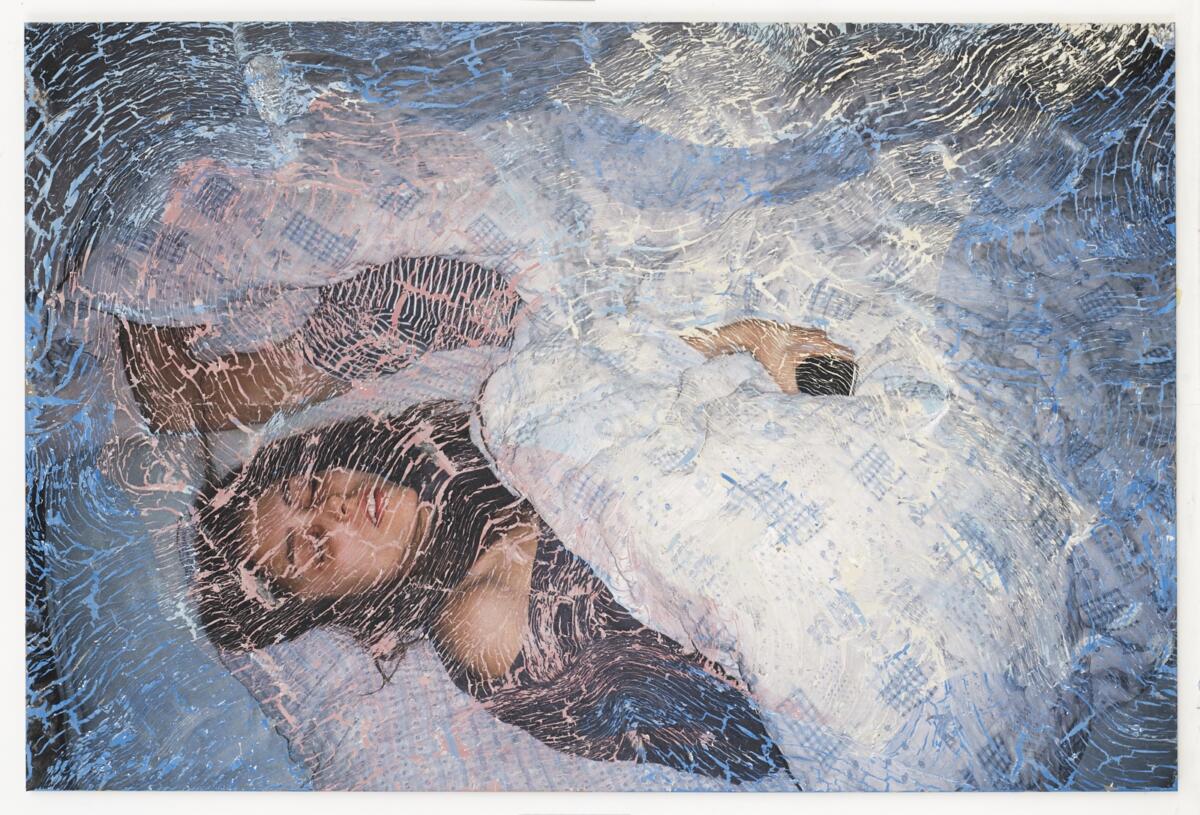

Another standout during this episode of slight commotion in the capital’s scene was an exhibition simply called Curl. The solo presentation by recently graduated Yong Xiang Li was not officially part of the gallery festival’s program and awaited its visitors in a second showroom upstairs at gallery LAYR. Featuring see-through closet-like towers with delicately painted canvases on top of them as well as a poetically atmospheric video work in the window of the space, this show felt like an adventurous dream and tender awakening at the same time, mixing feelings of desire and contemplation of the fact that for now we’re forced to rest.

In terms of building alternative structures, two projects managed to impose a strong DIY mentality despite all difficulties brought upon cultural workers this year. The critically acclaimed festival steirischeherbst’ for example turned into Paranoia TV, a specifically developed online format that collaborated with national radio and media platforms, presenting a diverse program of screenings, talks, and other interventions instead of physical exhibitions.

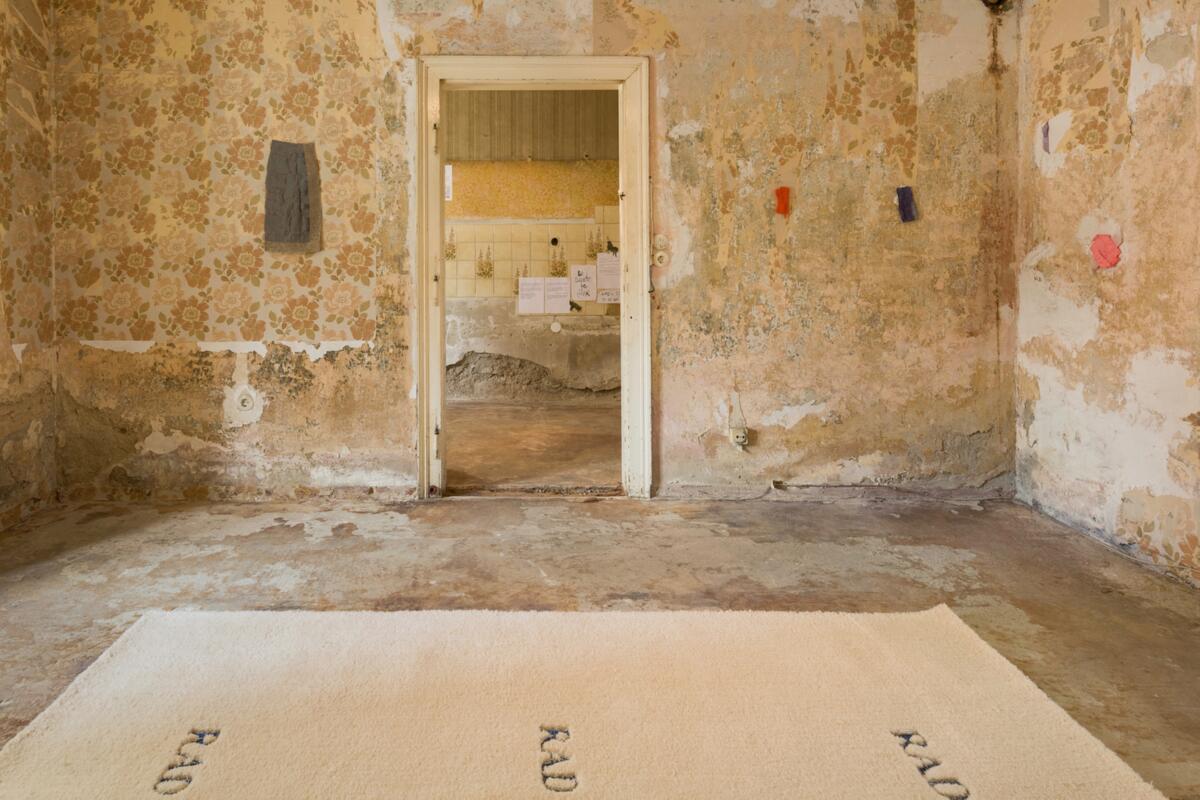

Opposing the currently and somewhat agitated Austrian fair landscape is the new not-for-profit initiative Haus Wien, which has originated from a group of people affiliated with Vienna’s independent scene. Having conceived their first edition late this September, the project presented a diverse selection of artistic expressions, selected by a jury and curated on-site at a former residential building in one of Vienna’s outer and more working-class districts: Simmering.

Especially worth mentioning are the shared room of curator Tom Leo Engels opposing the works of Hana Miletic with vintage photos by Teenie Harris presented by EXILE, Angelika Loderer’s Space between a kiss, an animated video work by Philipp Ulman in the furthest down basement space of the building as well as the works of Albin Bergström and Laurids Oder right next door.

Concluding this 2020 round-up is a recommendation to go visit the exhibition ANDY WARHOL EXHIBITS: a glittering alternative at mumok once it reopens. Curator Marianne Dobner and exhibition designer Spilios Gianakopoulos did an amazing collaborative job on the marvellous glass displays in which early Warhol works on paper are iconically lighted, held up by magnets. Focussing on a less known episode of Warhol’s oeuvre as well as restaging some signature exhibitions, this showcase excites amateurs and art professionals alike.

Ones to watch:

Wonnerth Dejaco – The new gallery in Vienna’s first district has presented a strong first show by Georg Petermichl and is picking up on mostly local artists, providing a platform for new voices and new discussions within the regional commercial scene.

Kevin Space – After relocating to their new space just around the corner of the previous one, the team of curators behind Kevin Space continues to provide some of the most exciting and carefully put together independent exhibitions found in the capital.

Kunstverein Schattendorf – Their group exhibition Ballast Palast curated by Goschka Gawlik and Siggi Hofer looked like a real delight and the remote countryside location of the exhibition space is particularly appealing. Eager to see more!

***

Vanessa Gravenor | Germany

In Berlin, the culture sector has been particularly hit with the shutdown of museums and an almost moratorium on public events since March. Within these limitations, institutions have had to rethink ways of connectivity in order to resuscitate an industry that once relied on presence and assembly as its modus operandi. Some of last year’s highlights included self-organized initiatives that work outside of traditional institutional structures, while other virtual offerings expanded what we think of as being local. My own viewership and consumption of art has been tampered by the pressures of the times, a damp introspection, and a contemplation on the bounds of screen-based spectatorship.

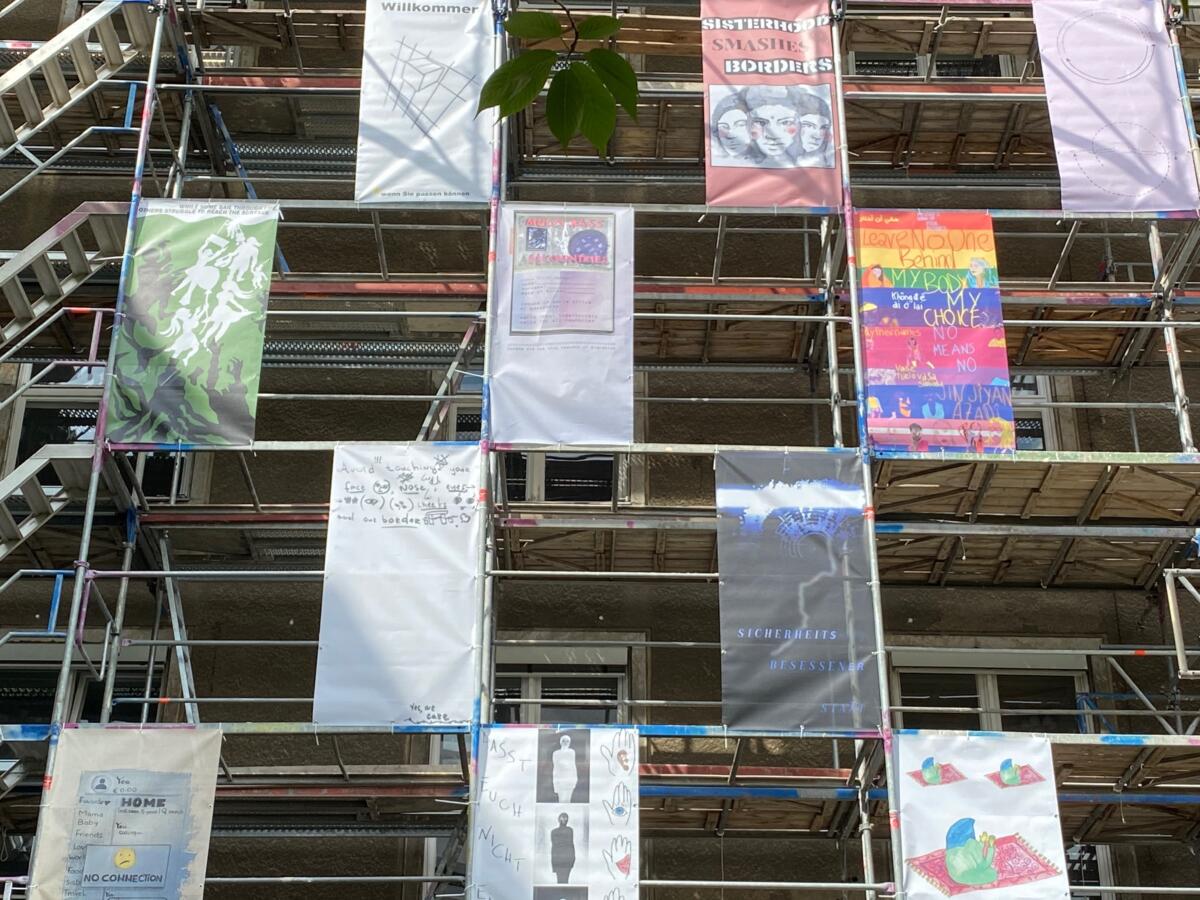

Self-Organized Initiatives: “The Economy of Borders”

Organized and curated by Marina Naprushkina and Joulia Strauss, “The Economy of Borders, We Lost Our Soft Soul by Crossing the Borders” commissioned 37 artists to respond to the pandemic and the crisis. Alongside the new isolation in April, the initiative responded to the closure of the European Borders to those seeking asylum, the abysmal conditions in refugee camps, as well as considered its consequences on women often tasked with care work. Of the 37 artists, many had migrant backgrounds and themselves had sought asylum, like the collective The House of Women for Empowerment & Emancipation, a platform for women refugees and feminist activism. The initiative, which I participated in as an invited artist, consisted of some 50 posters that were hung on the façade of a district town hall in Berlin. In order to assemble, which was prohibited in Germany at the time, the vernissage was instead a registered protest outdoors where different participants read stories sent from people detained in camps, attesting to the ongoing state of precarious life, made all the more so by the pandemic.

Online Stream: Aphasia 3 (2019) by Jelena Juresa

While 2020 felt like the future, built on a narrative of capitalist progress, was fully canceled, this year was also a time to consider pasts and the unequal presents they have founded. Among such works that meditated on these traumatic pasts and the continued silence surrounding them was Aphasia 3, a three-chapter film series by artist Jelena Juresa that I saw online at Bi’back, a project space in Berlin focusing on topics related to post migrant and post-colonial perspectives, and aashra, an online program part of Ashkal Alwan in Beirut, Lebanon.

The work takes its name after a phenomenon featured in Ann Laura Stoler’s book Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Stoler characterized the silencing of France’s colonial past in contrast to amnesia that has typically been used as a metaphor in characterizing the effects of war or genocide. Aphasia is a systematic loss of words, a forced forgetting that has political dimensions. In Aphasia 3, we see a seated woman, journalist Barbara Matejčić, alone in a dance hall. She describes the club scene in Belgrade in the 90s during the Yugoslavian Wars and then recounts a present-day confrontation with a perpetrator of a war crime, a soldier famously photographed kicking a corpse, who now plays in Belgrade’s nightclubs. The work questions the apathy of the audience to identify this perpetrator, and the phenomena of disidentification necessary to go on with life after the war. Ivana Jozić then performs a chilling choreography that vacillates from embodying the guise of the club goer, the DJ, and the gesture in the photograph. All gestures together reveal a brutality that would otherwise not be evident if not for the collapse of the three into one.

Exhibition: “The Invented History” at Kindl

Curated by its new artistic director, Kathrin Becker, “The Invented History” reinstated the topic of the archive and artistic fabrication of historical forms by bringing back pivotal works by Akram Zaatari’ Faces to Faces (2017) and Yael Bartana forged archeological ruins of weapons, titled R.I.P, with the specs of each gun after. The standout work was Jean-Ulrick Désert’s work Negerhosen2000 / The Travel Album (2003/07), which consists of photo documentation of the artist’s performance tour of Germany where he dressed in lederhosen. In contrast to the black or brown leather of this traditional/national folk costume, the artist chose leather that mimics Caucasian skin. As a black man, the artist, through trickster juxtaposition, questions the country’s folklore, and the invisible colonial and racism embedded within forms and practices.

“Unlearning” “Radical Care” “Plants”

Some topics that arose frequently during the last year were unlearning, care, or musing on botany.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, who exhibited and spoke at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) this fall and KW this winter, discussed the unending potentialities covered over by the imperialist project.

Radical Care by edna bonhomme in her podcast Decolonization in Action, specifically the episode “Finding Pleasure in the Age of Corona” with Lee Richards and Camille Barton, two queer decolonial activists, their practices of healing marginalized communities, and combatting anti-blackness.

The radical potential for botany at The Institute for Endotic Research in In Weaving Shared Soil with Luiza Prado de O. Martins and Milena Bonilla and their discussion on Rosa Luxemburg’s study of plants while she was imprisoned.

***

Krisztián Gábor Török | Hungary / UK

This short entry, rather than collecting highlights, serves as an opportunity to summarise some thoughts I gathered from a series of experiences in the last nine months. Two months ago, I watched an online roundtable conversation where the audience asked a question, can we take further anything from the months we learned from the online sphere? I am not here to cherish the digital image, but I would be a fool to ignore how the last nine months affected my thoughts on the necessity to be together.

I quickly found myself in online reality through the reading group organised by tranzit.sk and the curator Borbála Soós. The program was an addition to the postponed exhibition Ecologies of the Ghost Landscape The Word for World is Forest curated by Soós. We were reading and discussing texts on the ongoing climate crisis and wilder ecology. This occasion was the first time during the pandemic where I experienced the potential that these online meetings have, in bringing together cultural practitioners from different localities. In this space, the group lifted contemporary ethics applied in art discussion to a more diverse patient area of multiple points of view. The next realisation was when I visited the physical exhibition in July. The artworks became just another set of opinions, complimenting the web of thoughts I learned through fellows from the reading group. Our collective learning and sharing experience destabilised the exhibition format’s hegemonic structure, creating a more horizontal layout with the preliminary reading group.

Parallel to this, I became involved in the Hekler Assembly, a transnational peer learning group. The Assembly Reading Groups ran from May through July and discussed various topics from collectivity to practising self-instituting. Hekler was something I could count on during the most challenging months of separation. It gave me the chance to host my own reading group while also pushing my limits with the difficulties of being together in online rooms, due to time zone difference, loss of attention, or just online exhaustion.

The summer easing of restrictions brought a temporary sense of normality and a break from the online reality, and inspired a revelation about the necessity to be physically together during the 5th Minitremu Camp organised by Monotremu (Laura Borotea and Gabriel Boldis). For those who are not familiar with Minitremu Art Camp, it is a camp in Transylvania for high school where invited contemporary artists host workshops to teach critical thinking through contemporary art in an informal setting. I attended the camp as observer, participant, and sidekick to Laura and Gabi. As the photographer of the tender images here and my ally during the camp, Andrei Becheru wrote to me, it would be impossible to describe with a photo, or in my case with few words, the feeling of being physically together this year, almost like a temporary family. All those who were present created an intimate space and affective fiction, made up of not only the workshops, a self-organised party in the courtyard of B5 studios, long night conversations, shared meals and many more unnoticed moments of sharing space. The closeness and intimacy that Minitremu art camp brought to me still fuels me on the darkest lonely days in the end of this year.

Autumn came and we were forced back to our screens, it was a shock after the summer days of supposed normality. However, my participation with my collaborator Daniel Godínez Nivon in an online laboratory Re–Directing East x Empathic Pedagogies: Future Intimacies, curated by Marianna Dobkowska, at CCA Ujazdowski Castle, running from October until the middle of November, brought me a new revelation about the online sphere. The residency was meant to run offline, but the pandemic redrew its plan and focus. The laboratory’s goal became to use educational tools to gap physical isolation between the group members in Mexico, Poland, Costa Rica and Berlin. The exercises done by the group was an explosion of imagination, where the Zoom meeting room became just a means of communication. We had to stop seeing each other through pixels and relied on the intimacy of sounds and the potential of imagination, something that drew us closer to one another. Opposed to the stark reality of those in Warsaw, with me included, after the Tribunal decision on the 22nd October, the still ongoing Strajk Kobiet, our digital group became a form of care and escape from the troubles of reality. On one occasion, we imagined ourselves in our own hands or embodied the dreams of others. The image here shows a moment from our shared online choreography, dancing together to Meredith Monk through typing.

Marlies De Munck and Pascal Gielen in their short recently published book NEARNESS: Art and Education after Covid-19, compares people to works of art and how they lose their aura in the Benjaminian sense, what they call ‘nearness’. In dialogical or socially engaged art, this notion is hardly reproducible by the floating heads in an online call. As Minitremu presents the necessity to be together will be enormous after the pandemic ends. However, when we go back to real-life events and workshops, as the laboratory shows, we have to take all the experiences learned and fueled with this burst of imagination, to learn to relate to each other and rethink how we used to create intimacy and closeness.

***

Joanna Warsza | Poland / Germany

This unforgettable year, 2020, was marked by a perpetual split between isolation and social upheavals, between the endless immobility of Zooms and the uplifting agility of the Black Lives Matter or Polish Women’s Strike rallies. And somewhere in between the digital and the analogue, alongside the sinking of the busts of slave traders, what has become more and more apparent is the asymmetry between the privileged and the rest, and the need to dismantle a colonial, patriarchal, Eurocentric and Western-centric mindset. In Eastern Europe this reality is even more complex because we inhabit a state of ‘coloniality without colonies’, ‘self-colonisation’ and the va-et-vient between inferiority, superiority, and neo-nationalist drive.

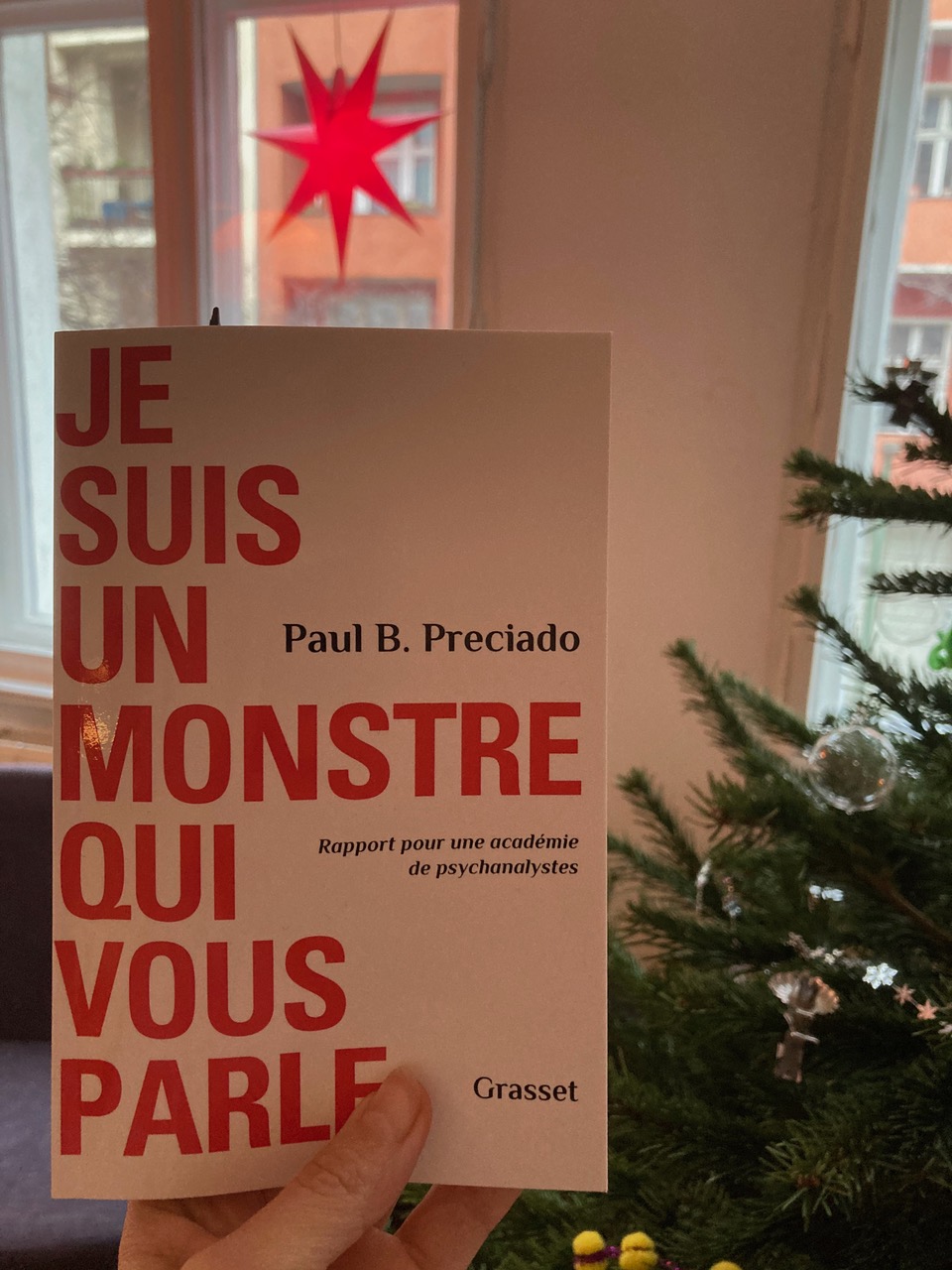

Some of the invaluable companions in these processes are for me the philosophers, artists and public intellectuals, such as thinkers Paul B. Preciado, Ewa Majewska or Achille Mbembe; art historian Bénédicte Savoy and the economist Felwine Sarr; writer Oxana Timofeeva; artists Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Janek Simon, Nora Al-Badri, Edona Kryeziu, Michael Rakowitz, Ulf Aminde, Zorka Wollny and the curators of the 11th Berlin Biennale. Taking on the minority perspective, they concoct the affirmative strategies in which feminism, participation, AI or technology function beyond their representation as a means of survival. Meanwhile the term ‘biennale of resistance’, has gained new momentum thanks to the East Europe Biennial Alliance.

I was also inspired by those whom I call, after Stuart Hall, ‘familiar strangers’: Yuriy Biley, Yulia Krivich and Vera Zalutskaya, artists, curators and initiators of ZA*ZIN (*foreign artists and artists living in Poland); Maciej Zaremba’s autobiography as a reminder that one should rather learn about our shames not victories; or the writings of Kosovar anarcho-intellectualist Sezgin Boynik. Unfortunately there were many pandemic victims – a unique space of coexistence in Paris, La Colonie, led by Kader Attia and his family, had to close. And an inspirational and generous curator Marion von Osten, as well as anthropologist David Graeber sadly left us far too early.

It was also an unusual year in which, just as in childhood, one could again follow the change of seasons. It was a year in which art, more than ever, became for me a form of recovery, a way to overcome isolation and a negotiator of interdependencies. At the height of the pandemic in the spring, together with Övül Ö. Durmusoglu, a curator-friend and a neighbor, we organized an exhibition in the windows and balconies of our Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood. Die Balkone will now become a cyclical event raising questions about translocal solidarity in the international Berlin art community. I spent the summer with Cabinet Magazine editor Sina Najafi, collecting and editing the e-mail correspondence of our late friend Warren Niesłuchowski, and preparing an exhibition about his homelessness by birth and choice, currently on view at the Foksal Gallery Foundation in Warsaw. Also finally we had two books released: A Reader on Alexandra Kollontai, a Russian feminist and activist who first introduced abortion rights which was co-edited with Michele Masucci, Maria Lind and our students at the CuratorLab at Konstfack University in Stockholm, as well as Synthetic Folklore, our monograph on Janek Simon’s work.

The autumn of the patriarch has arrived – writes Paul B. Preciado, a process of upcoming paradigm shifts where so many asymmetries, structural violence, daily extractions on all levels have to be deconstructed and swapped for planetary relations. Art and especially public art can be helpful and necessary in these knotty processes. There will be lots to do and undo.

***

Maja and Reuben Fowkes | United Kingdom

2020 was an incredibly challenging year for contemporary art from the lockdown of the spring to the stop/go of coronavirus regulations that were a nightmare for institutions and even more disruptive for artists, with shows cancelled, postponed or installed in empty venues. Film and media based practices had a distinct advantage as the artworld switched online, exhibitions turned into screening festivals and everyone adapted to the novelty of virtual openings, curatorial tours and art conferences convened from someone’s bedroom. At its best this felt close to the initial intentions of the East European net.art movement of the early 1990s that saw the potential of new technology to make art more geographically-just, democratic and accessible. However, more often such online encounters were a partial and disheartening experience. Although the virtual turn enabled new kinds of disembodied mobility that made it possible to participate in art events in Kraków in the morning, Prague in the afternoon and London in the evening, it deprived us of the liquidity of social interaction.

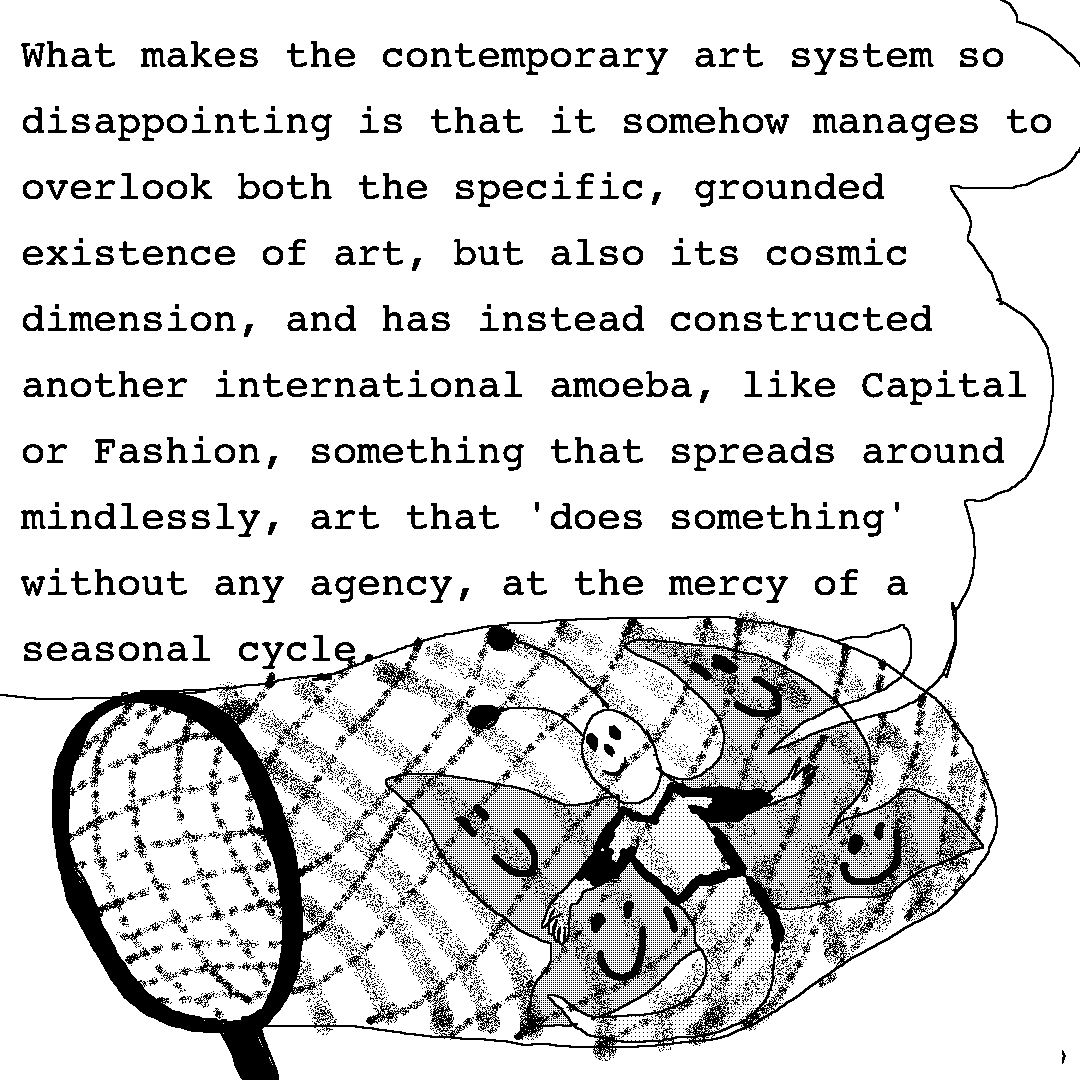

Expecting the focus of global concern to be on the now postponed COP26 Climate Summit in Glasgow, UK institutions devised an appropriately topical exhibition programme for 2020. However, the Hayward Gallery’s Among the Trees, the Royal Academy of Art’s Eco-Visionaries and Camden Art Centre’s The Botanical Mind turned out to be examples of the inadequacy of apolitical curatorial approaches to the natural world that steer the discussion away from the systemic roots of ecological crisis in extractive capitalism and colonialism. The shortcomings of such exhibitions were exposed by the pandemic itself, the causes of which are inseparable from the environmental factors of climate disruption, habitat destruction and industrial agriculture.

Were it not for travel restrictions, we would have liked to see the Riga Biennial RIBOCA2: and suddenly it all blossoms curated by Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel, which explored ways of inhabiting the world in light of the new circumstances, as well as The Penumbral Age: Art in the Time of Planetary Change, curated by Sebastian Cichocki and Jagna Lewandowska at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, which we could only experience in its online variant. Equally, Manifesta13 in Marseilles was very much overshadowed by the pandemic, but hidden within its fragmented format were a number of compellingly conceived projects. It was a real treat therefore to see Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics curated by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel at ZKM in Karlsruhe, making it for us the standout exhibition of 2020. With a strong presence of research based and social practices, the exhibition delved into the entangled social, political, ecological and geological spheres of the planet, including investigating humans as hosts to a myriad micro-organisms, bringing a timely understanding of the symbiotic realities of terrestrial life.

Back in January, the grassroots platforms Keep in Complex and Migrants in Culture organised at Raven Row in London an activation day for migrants, people of colour and allies in the cultural sector, with a strong voice of artists from Eastern Europe, including Alicja Rogalska and Bojana Janković. Days before the beginning of the Brexit transition, concerns were shared over the increasing precarity and uncertainty facing European artists in the UK and the implications for the non-profit cultural sector of the hostile environment. In the face of a nationalist cultural agenda based on reviving imperialist fantasies and a shallow corporate rebranding of global Britain, the artist Kathrin Böhm called for a ‘meaningful internationalism’ based on solidarity and cooperation. With the period of actually existing Brexit about to begin, these questions are as pertinent as ever, not least for East European art and artists in the UK.

***

Anna Remešová | Czechia

So many things have happened behind the closed walls of art institutions in the Czech Republic this year! For almost five and half months, no one could visit any exhibition, library, or archive, yet there are still events to talk and gossip about.

We have new directors! One entirely new: Polish curator Alicja Knast will start in the National Gallery Prague this January. It matters a lot because we have been waiting for a new director for more than one year. In the meantime, the interim director of the NGP, Alena Anne-Marie Nedoma, has managed to get rid of the Jindřich Chalupecký Award, the educational department, and the nice café on the ground floor. Oof, what more?! The second director is not-so-new: Magdalena Juříková won the open competition for the directorship of Prague City Gallery, which is not as closely observed as the National Gallery but still of great importance in the local contemporary art scene. Unfortunately, the re-election of Juříková, who has run the gallery since 2012, won’t bring any changes, which is a pity because the gallery, with the potential of such a great 20th century art collection, really needs it.

Talking about the Prague City Gallery, the initiative tranzit.cz prepared for their gallery’s space the first edition of the Biennale Matter of Art, which was entitled “Come closer”. Luckily for the biennale, in July and August, it was possible to literally come closer, so it was probably the only big art event where we could actually see anything or meet anyone in person. The biennale is part of the East Europe Biennial Alliance that builds crucial spaces for cultural (and political) opposition to the nationalist and conservative governments of the Eastern European countries. The Czech Republic still holds quite a liberal position in this region, but this could all change with the upcoming economic crisis. And as we have seen throughout the year, culture was the last area the Czech political representatives thought of (visual artists were even excluded from the financial support).

What I really enjoyed

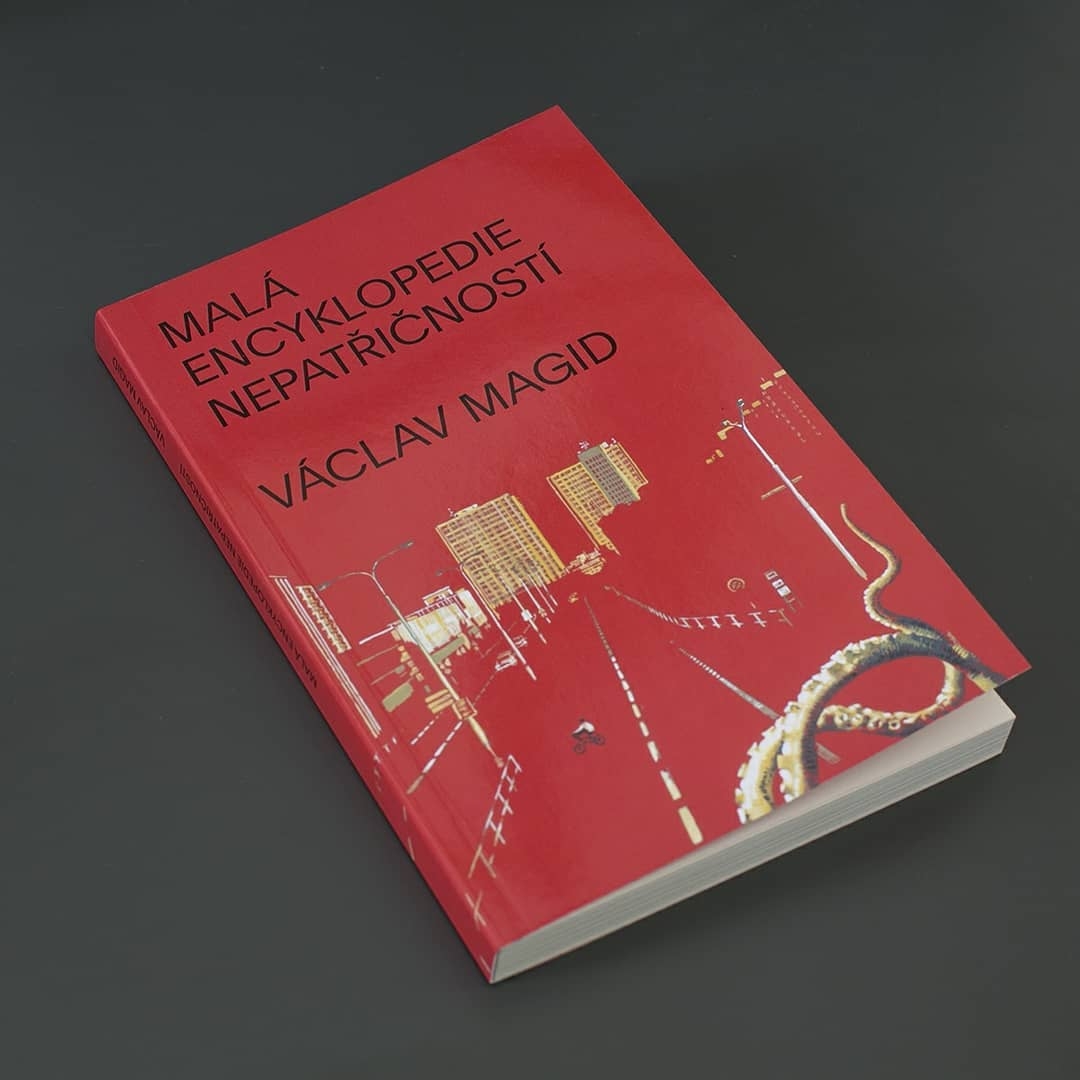

Among the students of the Faculty of Arts at Charles University, there emerged a new initiative called Decolonization which aims to start a discussion on the revision of university education with regard to Czech colonial complicity. Questions on decolonizing the collections and expositions of the art galleries and museums will be more and more frequent in the following years, and it’s good to see that there has already been at least some initial debate on this topic. Among other things, I enjoyed the collection of short videos selected for the Other Visions competition, curated by Tina Poliačková and Lumír Nykl, which takes place every year as a part of the festival PAF Olomouc. The fairytale and gloomy atmosphere of the artworks were a good fit for an end of the year full of insecurities and anxieties, the curators succeeded in gathering contemporary visual images of something that we could call post-human collectivity. The last picks will be books – both very different, one is the Malá encyklopedie nepatřičností (Small Encyclopaedia of Inappropriateness) by Václav Magid which is a brilliant assemblage of anecdotal events of the late-capitalist society, and the second one, Dějiny českých dějin umění 1945–1969 (The History of Czech Art History 1945–1969) by Milena Bartlová, a long awaited research result rehabilitating the post-war art historian institutions, personalities, and methodologies developed under the regime of Czechoslovakian state socialism.

***

Sylwia Serafinowicz | United Kingdom

View from My Home Office

Racism – Sexism – Homophobia. Recognise the Connections

This year served us an explosive mixture of fear, frustration, excitement and hope. For many of us it was an opportunity to look inside ourselves and spend more time with our own work and thoughts, that is why my account of 2020 is such a personal one. An unexpected halt to the usual ways of work and leisure forced upon me (and the rest of the world) new ways of working, connecting and caring for others. Soon, I learned to appreciate a surge of zoom talks and seminars that effectively connected thinkers across the oceans and led to a global exchange of information, frustration and rage (in the aftermath of deaths of Belly Mujinga, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and many others). In the Polish context, the collective Syrena revived the memory of Maxwell Itoya, a merchant who died at the hands of the police at the 10th Anniversary Stadium in Warsaw in 2010. This new form of connectedness allowed the marches in defence of Black lives to spread faster and for protests in support of LGBT+ and then women’s rights in Poland, to gain unprecedented attention from the international media.

As Keith Piper remarked, by the end of May, when we were all completely ‘entrenched in the idea of the danger of outside spaces, young people decided that racism is a bigger pandemic.’[1] For me, and I am sure for many others, the decision to go outside and protest, meant compromising the security of the loved ones in our bubble. On the 13th of June, Black Lives Matter marches in London clashed with far-right counter-protesters, who travelled to London to ‘defend the monuments’ (a reaction to the toppled Edward Colston statue in Bristol, a slave trader commemorated as a philanthropist). The same day the a/political team, including myself, circled Parliament Square, Whitehall, the Home Office and the US Embassy, with a message to the government from collective Democracia, saying ‘Enjoy the Collapse’. The statement was displayed on a mobile advertising screen and later projected onto the Bank of England; while an image of a riot policeman was projected onto the Houses of Parliament and the Royal Courts of Justice (work titled Silence, 2018 – 2020). It was as much a response to governmental indifference to the issues raised by the protests, as it was a reaction to broader negligence highlighted by the inquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire and the Windrush scandal.

Thanks to Biennale Warszawa, we projected the image of a riot policeman silencing the passers-by again in Warsaw in the week preceding the second round of the presidential election, which largely focused on anti-LGBT+ propaganda. Silence was a warning for the strengthening of authoritarian rule and more violence to come. The collaboration with Biennale Warszawa, involving the above mentioned collective Syrena with their brilliant A Brief History of Violence 1989 – 2020, led to the exhibition We Protect You from Yourselves and culminated in a webdoc weprotectyoufromyourselves.com, looking at police response to protests. While I was experimenting with digital storytelling (shoutout to Filip Wesolowski), Karol Radziszewski used the medium of painting to record the defining moment of the summer protests in Warsaw. His Detention of Margot, 2020, depicts the activist, a founder of the Stop Bzdurom collective, in the moment of their brutal arrest on the 7th of August. The work feels like a crucial addition to his previous paintings from the series Poczet, 2017, which are Radziszewski’s own selection of Polish history-makers, some of them actively erased from the public memory due to their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Reality Stranger than Fiction

The pandemic pushed the boundaries of reality and by doing so, made fiction feel more probable. In June I saw the game The Last of Us Part II. Branded as a post-apocalyptic vision, its depiction of abandoned urban infrastructure felt eerily familiar when I visited the freshly reopened Luton airport a month later while travelling to Poland. Some of this new reality was also compellingly captured in 2 Lizards by Orian Barki and Meriem Bennani, a series of animations set in a COVID-stricken New York City. It channelled the anxiety and other familiar experiences of lockdown like nothing else I have seen, through its animal protagonists, which includes a cat voiced by Cady Chaplin, who plays a nurse at Lenox Hill Hospital who tells her story. I followed all episodes on Bennani’s Instagram.

The 2019 HBO series Watchmen once again proved fiction to be an effective platform to think about the here and now. Featuring Regina King, it depicts a fictitious (but to what extent?) race war in America. Significantly, the creators based the series in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the site of the 1921 massacre of the Black population at the hands of a white mob. The events unfold around a Klu Klux Klan robe found in a closet of a local police chief. Judging by Andres Serrano’s exhibition Infamous, presented at the end of October at Fotografiska, New York, there are many similar robes left in closets across America. Serrano presented photos of racist objects available for purchase on the internet, including KKK hoods, postcards of lynchings, products with racist labels, a paper shooting target depicting a Black man. It’s a method he has explored before using merchandise and paraphernalia from the Trump campaign. I cannot recommend highly enough Serrano’s talk with Dr. David Pilgrim, historian and curator of the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University on collecting and working with these objects.[2]

Against Gravity

In Plain Sight was a project that managed to defy the odds of this year. On the fourth of July weekend, the crew, comprised of a coalition of 80 artist-activists led by Cassils and rafa esparza, in collaboration with an impact team, a PR team, and a documentary film crew, commissioned a fleet of skywriting planes to spell out messages, written by the artists and activists, over for-profit, privately-run immigration-related infrastructures (paid by taxes) across the US. The planes flew over eighty sites, which included detention centers, immigration courts, borders, sites of former internment camps, and other related landmarks, leaving messages that the artists hoped could be seen by detainees from their windows. The artists had to overcome numerous obstacles, ranging from the logistics of organising a large-scale intervention during a pandemic, to convincing some of the Trump-supporting pilots to get the planes off the ground. All locations and messages were recorded on https://xmap.us, a project website where visitors can locate the proximity of their closest detention facility and make a donation to Detention Bond Funds. As the website explains: ‘Detained immigrants sometimes have the opportunity to be released on cash bond – which is like bail – while fighting for immigration cases.’ IPS successfully fundraised and changed people’s lives. The mission statement of this intervention stressed that ‘the liberation of the immigrant, LGBTQI+ and Black communities are deeply bound together’ and are necessary work for ‘a just and free world’.

From a badge that reads ‘Racism – Sexism – Homophobia. Recognise the Connections’ seen on my friend Les’s Instagram profile, to the IPS testimony, a message of solidarity, is the one I will carry into 2021.

[1] Ghost Town. Sylwia Serafinowicz in conversation with Keith Piper and Drillminister: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec-EiaPohsk

[2] See: Obsessing About Race: A Conversation about Collecting Racist Objects. https://www.fotografiska.com/nyc/event/online-obsessing-about-race-a-conversation-about-collecting-racist-objects/

***

Valentinas Klimašauskas | Lithuania

The online year of protests and memes

“All I dream is summer 2021” – we have all seen multiple posts like this on social networks.

However, 2020 was not postponed, as some of us had hoped for. The year 2020 was altered and corrupted by that creature which can’t even be called a microorganism. The term technically does not include viruses, which are classified as non-living. The infective agent is a piece of code which is capable of copying itself and typically has a detrimental effect such as corrupting the system or destroying data while also corrupting itself, copying into new strains, changing the existing power relationships into something completely different; something we are still trying to grasp, something we will find ourselves coded into much later, but hopefully before it’s too late. This year we had enough time to realise (I was personally in quarantine 4 times) that it’s the year of transformations, not a year of deep-freezing, a suspended status quo.

So what hints do we have from 2020, what strains and trends are here to stay?

In my quarantined experience, 2020 was the year of memes, global protests, and strong online presence, maybe even e-dominance (or e-vents, e-conversations, online programs). In other words, it was about new, open-ended and easy to share digital or hybrid aesthetics (memes, e-solutions, e-talks), expressing the suppressed and interiorised quarantine-radicalised angst in demonstrations, public events and gatherings. Covid was often exploited as a political instrument. In Lithuania, the politics of virus control was used to get more media presence and to temporarily raise the ratings of the ruling party. However, they still lost the elections, which also coincided with Lithuania having the world’s highest rate of infection, with a daily average of 98.6 new cases per 100,000 residents over the past week (during Christmas 2020).

A SHORTLIST OF EXHIBITIONS AND OTHER EVENTS

- “Splitting the atom”

CAC Vilnius and the Energy and Technology Museum, curated by Ele Carpenter and Virginija Januškevičiūtė

In this context, it seemed that the usual institutional exhibitions that took place in the no longer safe interiors of kunsthallen and galleries, lost their momentum, at least for now. For example, I was really waiting for “Splitting the atom”, an exhibition about the nuclear age, a topic which has been triggering the sociopolitics in the region to atomise, to fuse nuclear-reaction and start splitting public imagination and debates. The context is super heavily enriched and radioactive. Think of the Chernobyl disaster, also the TV series, which was filmed in Vilnius. Think of the Ignalina power plant which also had the same Chernobyl-type (RBMK) reactors, which was decommissioned as a condition for Lithuania to enter the EU. Think of its nuclear waste – most of the radionuclides in the spent nuclear fuel emit alpha particles and have a long half-life, so it will take several hundreds of thousands of years for spent nuclear fuel to become non-hazardous. Or think of Astravec Nuclear Power (Belarus), located 45 km to Vilnius, which is being instrumentalised by Lukashenka to hold his power. The geopolitical, ecological, speculative, artistic (a great artists list could be another example), and other lists of reasons why this exhibition is/was important are endless and very relevant, but the exhibition did not seem to receive the public attention it should have garnered under so called normal – it’s not easy to start forgetting using this old-fashioned word – conditions.

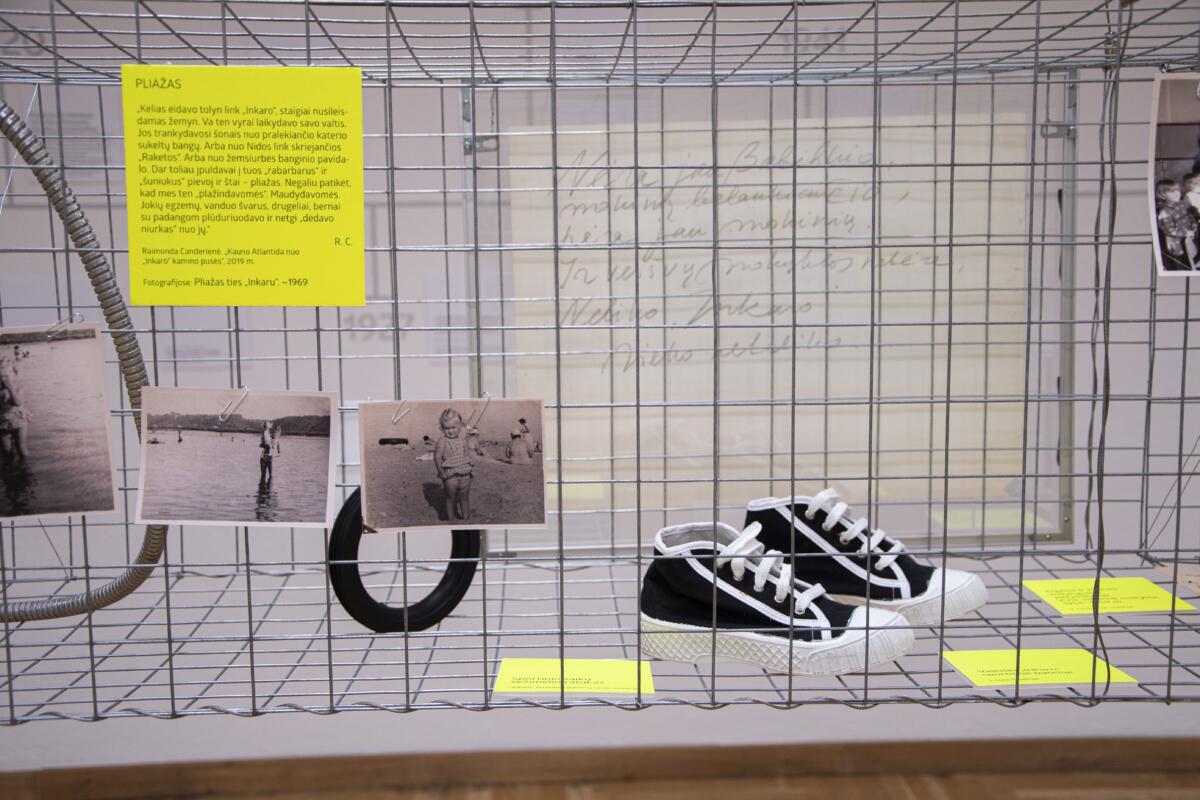

- “The great industry: “Inkaras” factory”

Kaunas Picture Gallery, Kaunas

Until 24 04 2021

Curated by Auksė Petrulienė

It’s a generous exhibition about the “Inkaras” factory where, during Soviet times, they produced now legendary sneakers, among other things. The exhibition continues as a series of shows dedicated to local industrial heritage and the employees of the factory. Its narrative has been created together with the former employees of the “Inkaras” (“Anchor”) factory, artists, and public activists – a round of applause and NYE fireworks to its curator Auksė Petrulienė.

For more info click here. - Swallow

Welcome to a new, doorless space in Vilnius: Swallow. The title of which, as the legend says, was inspired by looking at the sky. Located in a larger cultural hub Sodas 2123, Vilnius, it recently opened its non-doors with a second exhibition “Blueish”, by the duo Beatričė Mockevičiūtė and Gintautas Trimakas, curated by Audrius Pocius. Exhibition documentation has become more important than ever before; I only experienced this exhibition from its documentation, which was a beautiful balance of the coming light absorbed on photo paper (G.Trimakas) and its refractions in the installation (Mockevičiūtės).

For more photos click here. - Robertas Narkus, “The Board”

Robertas Narkus‘s solo exhibition “The Board” at Vartai gallery (curated by Neringa Bumblienė) was another pretty photogenic exhibition that looked like it was conceived to be photo-documented, to be perceived by looking at its documentation of some already photo-documented avatars and office landscapes.

For the exhibition documentation click here.

PROTESTS:

In the context of the global Black Lives Matter and women’s rights protests, the Belarusian demonstrations are exceptional because of their peaceful and poetic nature (not to mention the extremely brutal treatment of protesters). As artist and researcher Olia Sosnovskaya commented in a conversation:

“Peaceful Resistance and the Power of Poetic Dissent”,“humour and satire has always been part of the anti-state resistance in Belarus. Which seems quite natural, if one listens to the President’s statements: they are often absurd. This tendency to some extent also reflects the situation, when direct opposition to power is dangerous, so people try to be inventive in the ways of resistance. At the same time, the current state power itself is very ceremonial and its visual manifestations are omnipresent. So performativity and poetics of the ongoing protests could be indeed seen as an effort to re-signify the space, both physically (with red-white-red flags, for example, which now serve as anti-Lukashenko and not really nationalist ones) and symbolically. It is also very important that this poetics is not only reactive — just reacting to state propaganda — but it goes further, producing its own gestures. This time laughter also seems a regenerative gesture to me. After the despair, horror and mourning of the post-election state violence, people recollect their energy again and manifest: “we are not afraid anymore, we laugh at your face”. This is the liveness which resists violence and repression. Police brutality deprives you of dignity, and I see these poetic resistance tools as a way to restore one’s agency.”

More on trolling Lukashenka: “Every day, General-Frost helps the Belarusian revolutionaries”

In Minsk, people are painting or freezing the national white-red-white flag into the ice on the frozen Svislach River – in defiance to the ongoing repression.

- “Arresting Images, Arrested Bodies”