Joanna Sokolowska: Where do you come from as an artist? Your work is full of references to various cultures, philosophical and spiritual systems. Could you tell us your most important inspirations?

Jacek Zachodny: I come from the land of coincidences, travel, curiosity, wandering, observing the world, meeting interesting people. People who have created something. As a young man, I had this longing to become such a person. From childhood I also liked to work with my hands and create my own worlds. I didn’t like the stimulation of the outside world – the oppression – the adult world. Although important was the influence of my father, who wanted to travel the world terribly, and lived in such times when this was limited or impossible. As a result, there was a gigantic library of books about the whole world in the house. I grew up on them.

Your studies at the State Higher School of Visual Arts in Wrocław came at a time of great upheaval: the fall of Communism, the beginning of the transformation. Your first works were paintings in the style and energy of the “new wild”, which was popular in the 1980s. Although you have been painting ever since, you soon developed a versatile and multimedia approach, creating video works, performances, installations, sculptures made of any material, social actions, and writing books. How did this come about?

In the beginning there was indeed a fascination with Neue Wilde, in fact I wanted to study in Düsseldorf under A.R. Penck. Only by the time I had arranged the papers, he had already abandoned that university, and all that [Neue Wilde] energy was already running out. It was a terribly difficult time. In Wrocław we had this group called Karuzela Braders, we did three exhibitions at the beginning of the 90s which ended with some kind of scandal and police intervention. We were young and wild. As a young person I suffered terribly, wanting to express myself. I tried to write something, poetry of course…all in all it was somehow so natural to do this. Art school was a totally accidental situation because I had already studied archaeology. I went to art school because I was persuaded by a friend who knew I was writing something. And it used to be that all of it (music, set design, action, performance) was contained in art studies. Now it seems to me more separated through specialisation. Perhaps I owe something to the state of those times, that in the area of one exhibition or one action, to be the whole package of experience – sound, performance and action – with people joining in. I fell in love with the academy at that time because it was a time of revolution. It was 1988, when all the universities in Wroclaw went on strike to protest against the communist regime. I was active in the strike committee. As we carried out the strike, we lived in the school. It was an amazing time. The school was a totally living organism – pulsating, evolving, social. It was the kind of place you wanted to be. We had 24-hour studios. I could go in at two in the morning if I wanted to. It was about becoming an artist holistically.

But how do you go about transforming your ideas and inspirations further into concrete works? Could you talk about your process and working methods?

Artistic languages appear and sometimes disappear, and I try them out in order to express what interests me. For example, glass used to be present, especially in Wrocław.

Did you really work in glass?

Yes, I used to make glassworks – I experimented, I made large forms, various objects and installations, and then I abandoned it.

What happened next?

I wanted to make moving images, because glass is a solid after all. To learn the language of video was painstaking work, it required a gigantic amount of consultations. I often learn from others, looking for tips. Now there are tutorials of various kinds, but there is no tutorial like a person who is a specialist in a particular field. It’s different with performance. It’s such a dessert for me, a gift from life. I do it rarely, maybe once a year, when I feel the physical need to do it.

During our talks in Krzyżowa you repeated several times that art is a way of communicating with the world, and that you choose the means according to the message. So could we talk about the most important messages you want to convey to others?

Like every human being, I have my own construction of the world within me. The impulse is often born when dissonances arise in the clash between this imaginary world construct of mine and reality. The dissonance is usually some terrible thing like war. Because, according to my observations, we are all family in the world. I understood a long time ago that these bonds apply to all beings, including non-human beings, and everyone and everything deserves respect, some form of understanding, to be given a chance. When I experience assaults on this notion, that’s when I also react very strongly.

Your reactions, however, often manifest in a quiet and profound way, working in the areas of energy, meditation, the subconscious; their temporality goes beyond the present. You often inscribe the history of human life, of passing and death within the larger cycle of natural processes. The video series “Stories (Stories)” from 2007 is a good example.

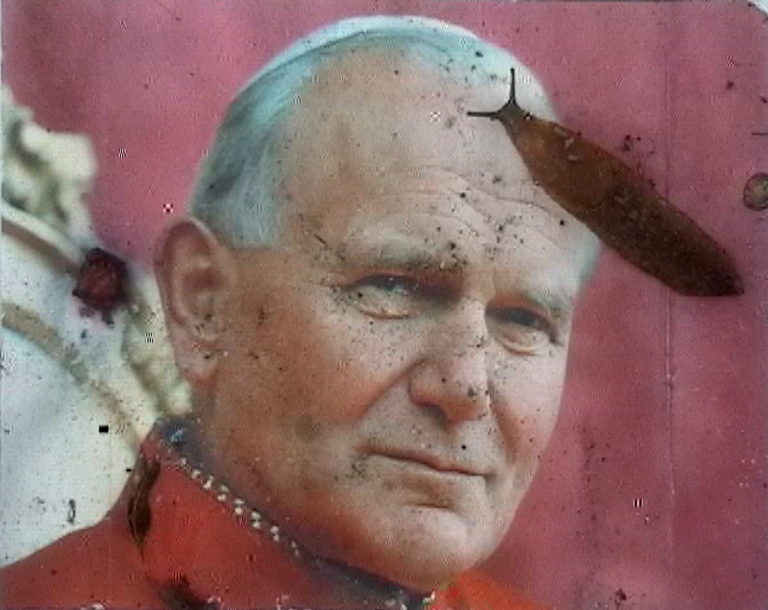

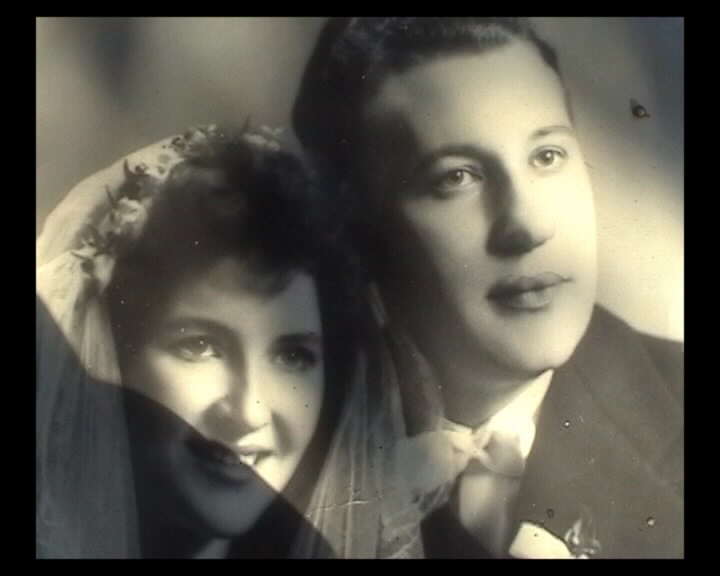

This series was created in a kind of limbo, when I had a lot of free time and began to perceive time differently through this experience. At the time, I was having such a local period, focusing on where I was living my everyday life. I noticed that when someone in the neighbourhood died, the heirs would erase that person’s entire life, throwing everything they had into the bin. And so stories about people falling apart, folding up, falling apart again and folding up came about. The starting point was a found wedding photo. I saw people with a twinkle in their eyes, in good moment. And then their life was over and now it was all in a container. The second part was created with a photograph of the pope [John Paul II]. I put these photographs outside, where they were exposed to changing weather conditions and the actions of various creatures. For several months I recorded the changes taking place in acceleration. At the end, nothing is left but a grey-brown abstract image. The video was looped: upon reaching the end of the decay cycle, the image becomes ‘rebuilt’ anew. The result was a philosophical work, about what happens to our emotions and ideas, about the cycle of life, death, rebirth. It was intended to be a triptych: ‘Faith, love, hope’. The last one – ‘hope’ – was to register the national flag that I had placed over the cat’s entrance to my house. The cat even put a mouse on it once. The photographs and the flag were thus subjected to unexpected interactions and transformations in the open air. I wanted to witness how the initial ideas behind these objects lost their original meaning and morphed into something else…beyond human control and values.

In this work, as in many others, you touch on what we tend to repress in Western culture: entropy, death. In the course of making “Death XXI”, for many years you conducted a series of conversations about the passing of time with people you met during your travels and acquaintances close to you. What did you want to find out? Why did you get involved in this work to such an extent?

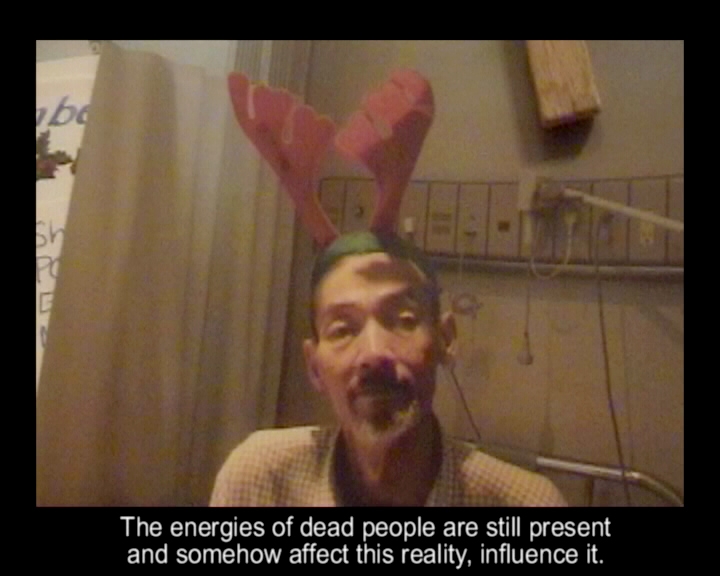

I feel that all my work is another stage in the expansion of mindfulness, and that the themes somehow appear on their own as the work develops. Before starting this work, I had my first experience of a loved one’s death, I was holding their hand… Soon after this I left Europe for the first time in my life and found myself in Asia. This journey lasted several months and was like a hallucination. In India, I found myself in a culture that treated death as in Breughel’s paintings: somewhere someone dies in a hut, here a bird flies, there a child cries and someone else rejoices. You can witness the whole thing. I don’t want to glorify this civilisation, but thanks to it I discovered that everything can function side by side and not in secret or isolation. I ended up interviewing about 100 people from different cultures about death. I was so obsessed that my friends thought I wanted to commit suicide. I wanted to contact as wide a spectrum of people as possible. The youngest person was about 14 and the oldest 93. I reached out to prisons where I interviewed people incarcerated for murder. I also went to a hospice. Being close to death wasn’t a link or goal, I also talked to people in full health, in their prime, happy with their lives, to people who were so-called simple and so-called complicated. I questioned people from Poland, India, and France. I asked about colour, about fear, about ideas of what comes after, whether there is something there, about transition, about personal stories, for example, whether someone witnessed death or had the impression of dying. I gathered a great variety of human thought, but it was impossible to build a definition as I believed in the beginning. After going all the way I came to the zero point that actually death is everything and nothing. It turned out to be everywhere. But I went to another level of mindfulness. And now, as I walk through the neighbourhood, or I’m in the woods, I hear different voices, voices of tragedy. I know that something is happening, that someone is killing someone, that there are dead slugs lying under the bushes, or an ant has just attacked a grasshopper. Just as there is a lot of life, there is a gigantic amount of death, more or less in similar proportions, right?

So let’s move on to the next path of expanding consciousness, which is your relationship with various non-human life forms.

It’s obvious to me now that we’re in the same wheelbarrow. I even like to imagine such a wheelbarrow with people, bears, mice in it… then the world seems full to me. Even in this room, although we don’t notice it, there are so many lives. That being said, I also experience the tragedy of the world… I’m not even talking about hunting anymore, but such a basic truth that there are dead – murders, death – everywhere. People erect monuments, altars, and memorials to themselves all the time. We do not have enough of these symbols for animals.The idea of an altar of animal sanctification came to me. I built such an altar (“Animal Altar/Sanctifications”, 2017) in a beautiful location on Tamka Island in Wrocław, overlooking the Oder River. I gathered various animal images in it, juxtaposed them with halos and other symbols of worship, and burned incense. I wanted to create an altar as if for my loved ones.

The sense of the commonality of life and death with animals in relation to the conditions of life on Earth accompanied you in your work “Drought” (2018) which was presented in Finland.

I don’t know if you know, but Finland’s ecosystem is extremely fragile and vulnerable to the threat of drought. Despite the abundance of water and forests, the soil is arid, shallow, and acidic. All it takes is a few dry seasons and it turns into a desert. That’s why I decided to create a desert garden there, a place of meditation where you can feel the cycles of nature beyond the human life cycle. From the moment of its creation, the garden changes under the influence of weather conditions, the planting of new random plants, or erosion, until finally nature takes over completely. I have collected animal bones from roadsides in addition to gravel and branches. While looking for things to collect I found out about someone’s family heirloom – a bag with the horns and shoulders of a hunted reindeer – through local colleagues. When I got it, I felt the presence of these animals, their gaze and breath. I used one of the bones for the installation and took the others into the forest and scattered them, giving them back to where they belonged, which was appreciated by my assistant, originally from Sami people.

Could you reflect on the role of rituals in your work? When and why did you start using it in the language of art? In which cognitive systems do you move?

You know what, I’ve never had any doubt that some other worlds are breaking through somewhere. And rituals sanction them, socialise them. A shocking experience was my first trip outside of Europe which was in 2004. I was in a difficult state, having witnessed the death of someone very close to me and then a week later, leaving Europe alone for the first time, travelling over land with very little money. All this together created a hallucination and the omnipresence of religion, demons, rituals, sacred places, participation in sacred rites. Meetings with teachers allowed me, against all odds, to keep some remnants of reality in the crazy world around me.

Do you by any chance aspire to be a shaman, taking us (the art audience) to other worlds? The kind of worlds that, here in Western cultures, we are afraid to touch, like the worlds of death, of spirituality?

This is how I perceive art in general, that it is a portal to other worlds. Sometimes you can open the door for a while, sometimes they collide. I don’t know if it can be said that way, but for me real art is about expanding consciousness. I’m surprised that people give up on art so easily, because it can be a path to self-development. It’s also very difficult. In my case, there is a lot of agony in the creative process, sometimes it’s unbearable.

And do you think at all about your place in the social world? How do you feel as a white male in today’s art world, which since your youth, has become more sensitive to inequality and privilege based on gender, race…. A lot of your work has been realised during your travels among people who don’t have the right to move freely and observe the lives of other cultures as you can. How do you deal with this?

I haven’t processed that. In my youth I myself stood in queues for a visa to West Berlin. I travelled illegally, by hitchhiking, without money, and I also worked physically abroad. I know that feeling.

But now it has changed.

When I travel, I feel that I blend in easily. For example, in Turkey or Iran, people asked me for directions in their languages. My whiteness, I feel, is only becoming fully noticed outside the Indo-European world.

I’m not just referring to your specific experiences, your interactions with people, which I assume were fair. I’m talking about your political and social awareness of your current privilege.

I think I have that. After returning from non-European travels, I was always devastated to hear people complaining about various problems. I think everyone in life should try to break out of their own culture. I don’t know what I can do with my gender, my skin colour, my background. I don’t feel like I’m privileged in some horrible way. Being an artist, I’ve had periods in my life when I didn’t know how I was going to survive the next day. I think I understand and respect people who have some basic problems. I have always wanted my work to be a transfer of ideas, to bring different cultures together through it and to build understanding.

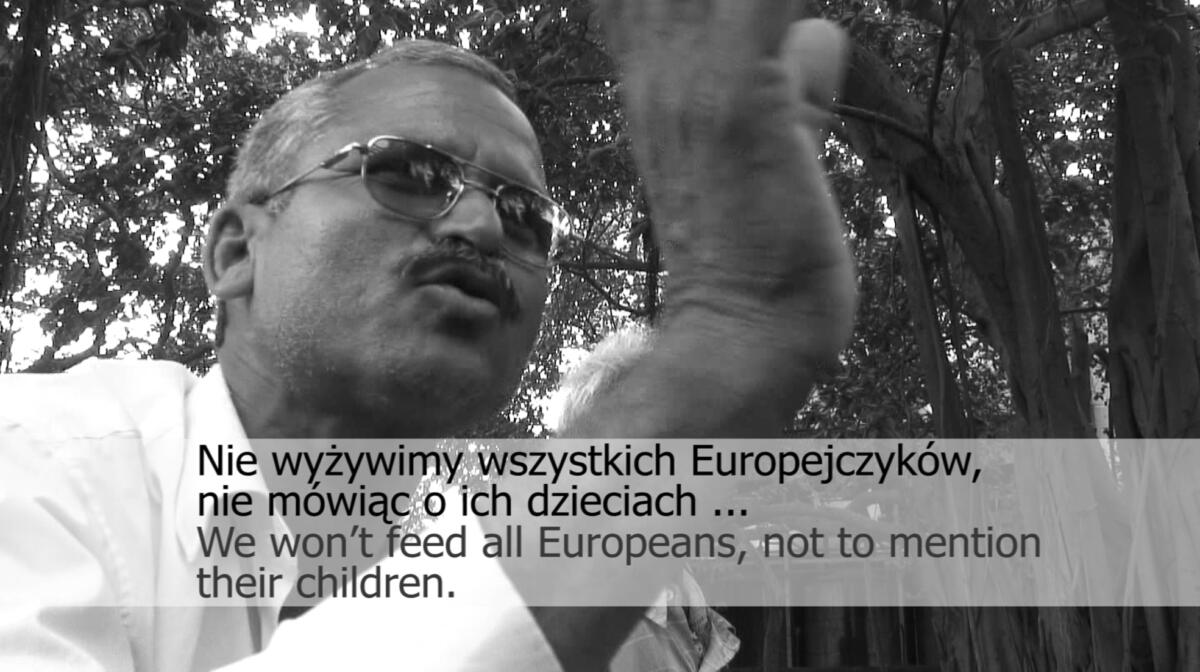

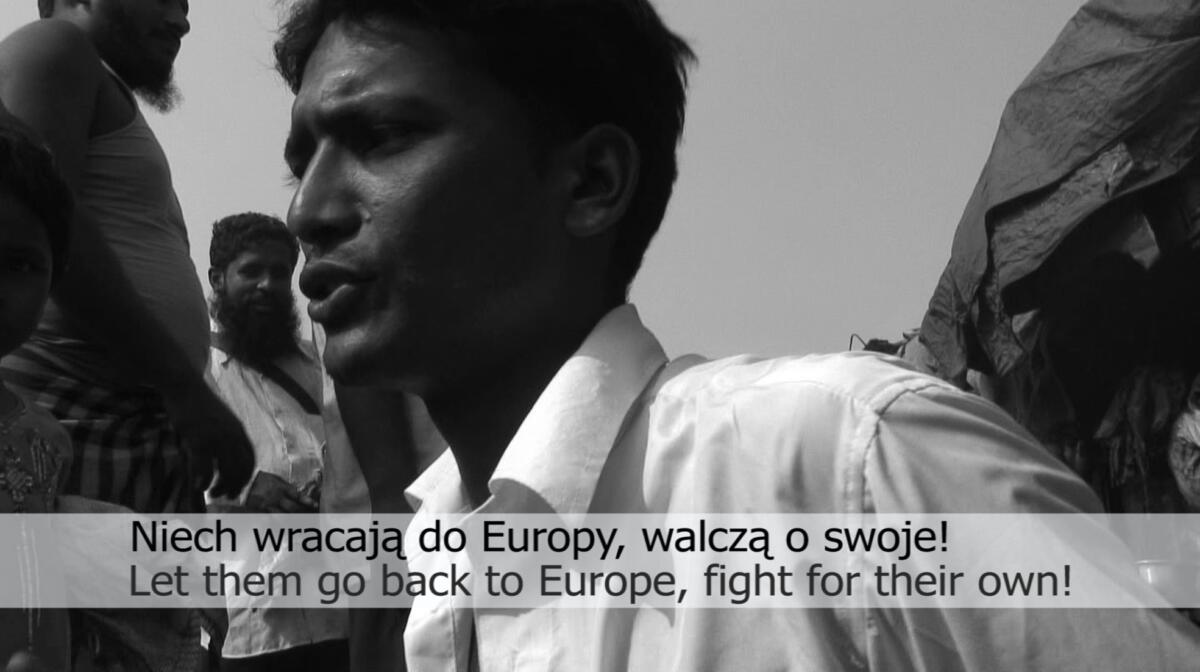

And you confronted racist prejudices directly in the video “Go Back to Europe” (2016).

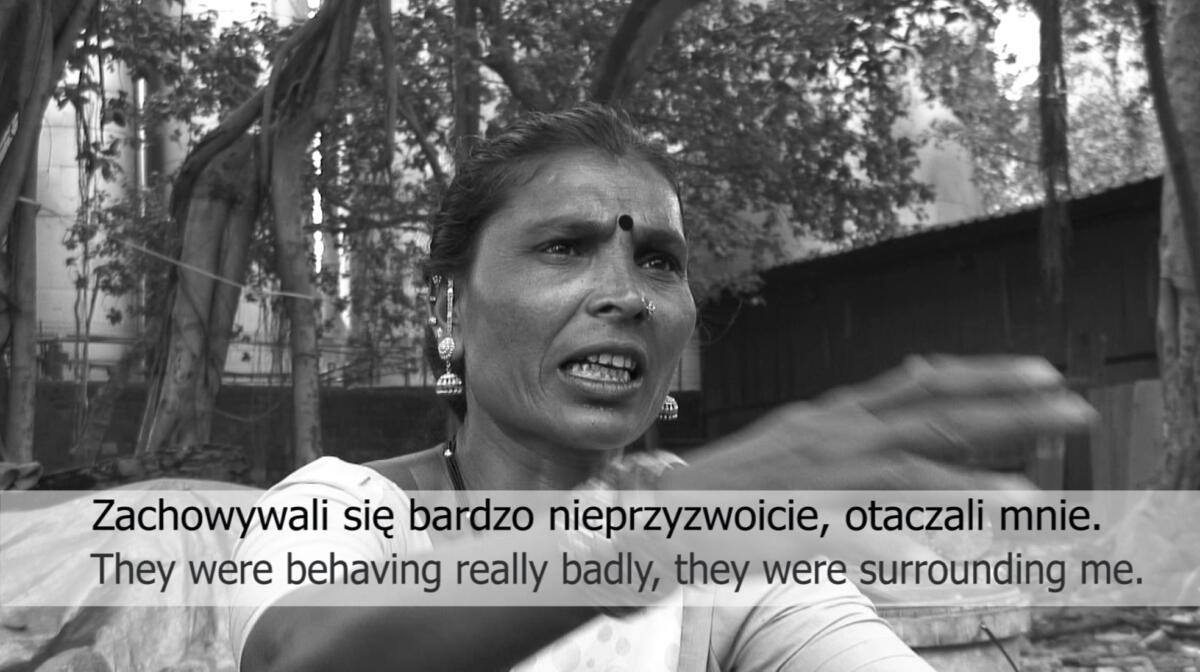

I don’t know if I had the right to do it as a white guy, but I felt I wanted to react to the so-called migration crisis around 2015. During the war in Syria, when millions of people were trying to get out, to save themselves, there was an increase in right-wing attacks on refugees almost all over Europe. In addition to the hatred, there was a lot of fake news, like refugees burning buses, running around with knives… In response, I used video cuttings from various projects involving people from India. I have re-edited these materials by adding a fake translation, visible in the captions, to their original statements in local languages, e.g. Hindi. These texts reflect racist prejudice, but this time, directed towards whites. It is as if these relationships are reversed. The Indian people speak about the problem with European migrants who had to flee because of some crisis or disaster.

What were the reactions to this work?

The film was shown in many places abroad, in Poland, even in the prison in Oława. The reactions were mixed. Some people were disturbed, some believed it was fake, some wanted to discuss racism.

Your books and stories are also embedded in your experiences of travelling in Asia. They do not fit squarely into either the Polish imaginary or the Western postcolonial idiom; they deal with more universal issues.

My book “Elektryka duszy” (Electrics of the Soul) is based on my experiences in India. Through writing I tried to understand the world in which beliefs, myths, rituals are something real. I wanted to explore the question of the stratification of reality into different worlds. The book is not a travelogue, of course. But I was confronted with a problem of classification in the Polish literary market, and I heard that the book did not fit in. It is not travel literature. So what is it? Because how can the protagonist just be, say, Ahmed, who is neither Polish nor Western, who has his own life and goals. I like writing, but art gives you more freedom than the literary world.

Tell us about the work you made at the Krzyzowa residency. From what I can see, you are also reacting to dissonance here, time from a planetary scale.

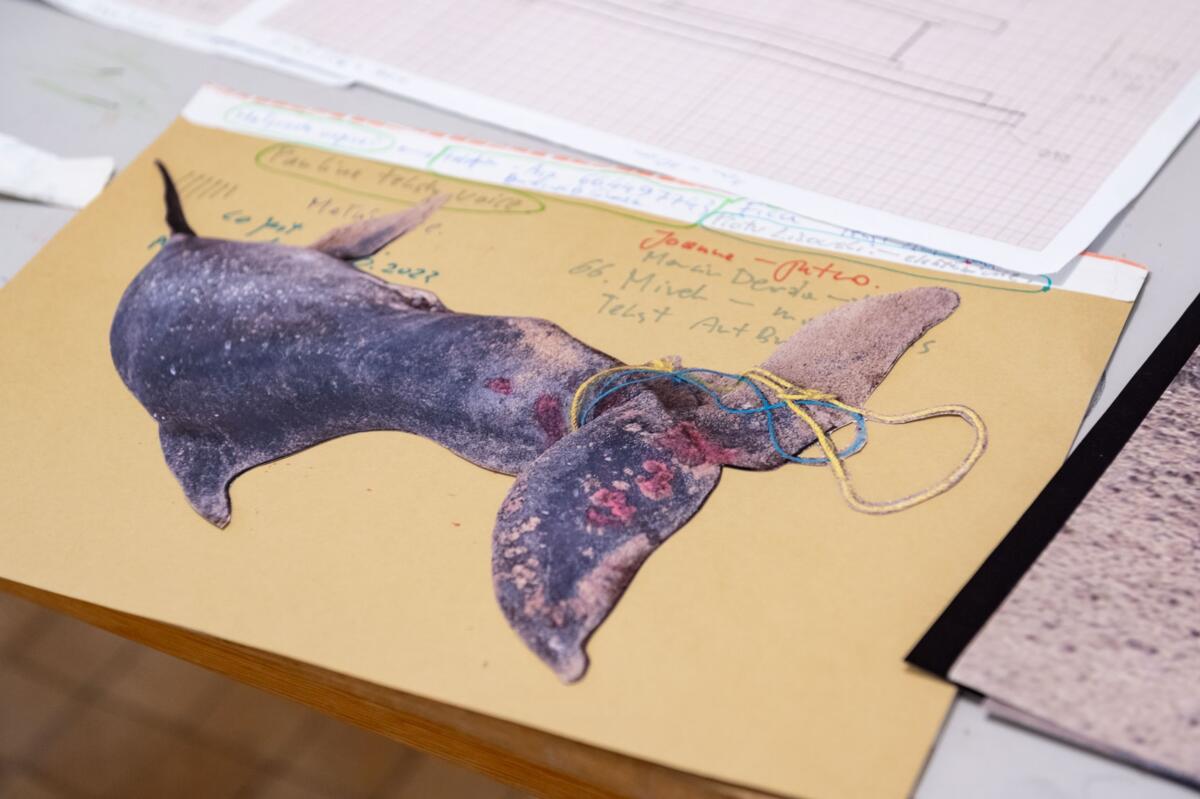

I am working on a fragment of a solo exhibition at 66p in Wrocław. In it I will focus on the inevitable, profound change, the breakthrough that awaits life on Earth. It will be about such a strange state of limbo, about the transition to another dimension of the whole Earth, about the gap between eras and the anxiety felt in many parts of the world. It is a time associated – as it most often is in history – with revolutions, wars and disasters, changes of ownership. For some, it means the apocalypse.

What specific works will appear in the exhibition?

The centerpiece of the exhibition will be a crater made of various waste from civilization. It is a symbol of the moment of impact, a time of chaos, of destruction. It will be a many-metre-high structure with a path to the centre. Above the crater I want to suspend a large, tangled, luminous object with neon. Maybe it’s light emitted from some already new world, and we are a fraction of a second after the change, or just before. I want to leave that open. Another element will be a new altar. It will symbolise the fall of certain ideas, religions, and the need for new beliefs and redemption. The altar will sanctify the martyr of the future, not a human but a dolphin. The dolphin sculpture will be created from silicone in a large, realistic scale. I want it to look fleshly. This figure will appear in relation to the extinction of dolphins in the world, especially now, in the Black Sea, but also with a specific, single experience. When I saw the body of a slain dolphin dumped on the beach by the ocean, it was unimaginable to me that we are such a species that cannot coexist even with such close creatures. In addition to this, I plan to make a large mandala made up of target sights, as if from weapons used to kill other people and animals. There will also be projectile-like objects that are supposed to be a bit like totems and a bit like brightly coloured candies.

The subjects will be accompanied by a video projection. I shot the footage in the Canary Islands. Before that, I was in Ukraine. And in that paradisiacal place I couldn’t tear myself away from the information about the war in Ukraine and my friends there. I had a sense of guilt, of dissonance. How was I supposed to feel calm, safe and relaxed when my friends were experiencing something terrible? I edited the video from some of the most beautiful, wildest views I encountered. It’s a meditative image of a world without people, some kind of dystopia. When there is a brief flare on the horizon, disturbing sounds begin to emerge, from the space of war. During my time in the islands there were catastrophic fires, shortly afterwards there was a huge earthquake in another place close to me, Morocco. All this was present within me.

And did the environment of Krzyżowa, the social space of the place, the educational programmes, have any influence on your work?

Thanks to the large studio space and my focus on the work, I was able to plan the objects for the exhibition and their placement very carefully. I also felt very satisfied doing a workshop with young people, although I was stressed about whether I could handle it. After talking to the educators, I decided that I would do a workshop on communication. I wanted the participants to realise that there is a huge amount of non-verbal lines of communication that we don’t use on a daily basis. I first introduced them to my work at Art Brut gallery in Wrocław, where I support artists with disabilities. These people often have very limited means of communication, for example they might not speak or they may have poor vision or may not be able to move freely. After the show, I suggested to the young people in Krzyżowa that they try to introduce themselves, to express themselves without words and their intentions towards the world or against something negative. Everything was super understood. A lot of works were created in total, some people did two each. We finished with a ritual, hung these works on the tree and that’s how the cult tree was created. I didn’t base it on any specific methods. The important thing was honesty, exchanging energy, and being in touch. We also talked about what the artist does. Maybe I encouraged someone to take this path? I confessed that it’s scary, that you often don’t know what you’re doing, and that it’s hardcore, but it’s freedom.

About the Konrad and Paweł Jarodzki International Artists-in-Residence Programme.

Imprint

| Artist | Jacek Zachodny |

| Place / venue | The international Konrad and Paweł Jarodzki artist-in-residence programme at the Krzyżowa Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe |

| Dates | 2023 |

| Index | Jacek Zachodny Joanna Sokolowska Konrad Jarodzki Krzyżowa Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe Paweł Jarodzki The Konrad and Paweł Jarodzki International Artists-in-Residence Programme |