Ewa Borysiewicz: How are you doing? I imagine you have an intense time behind you and a lot of work ahead as well?

Jósefina Alanko: I’m doing very well. Indeed, it’s quite busy at the moment. Since the award, a lot of people have been contacting me. I had numerous studio visits, and I started preparing a new series of paintings for the solo show at STRABAG Artlounge. It’s scheduled to open on January 11th, so a not too distant future. I’m already in working mode.

In the artist’s statement you sent me, you described your process as stretched out in time: it takes weeks or even months for a painting to materialize. I’m wondering, how do you prepare for an exhibition? Do you already have an idea how it will look?

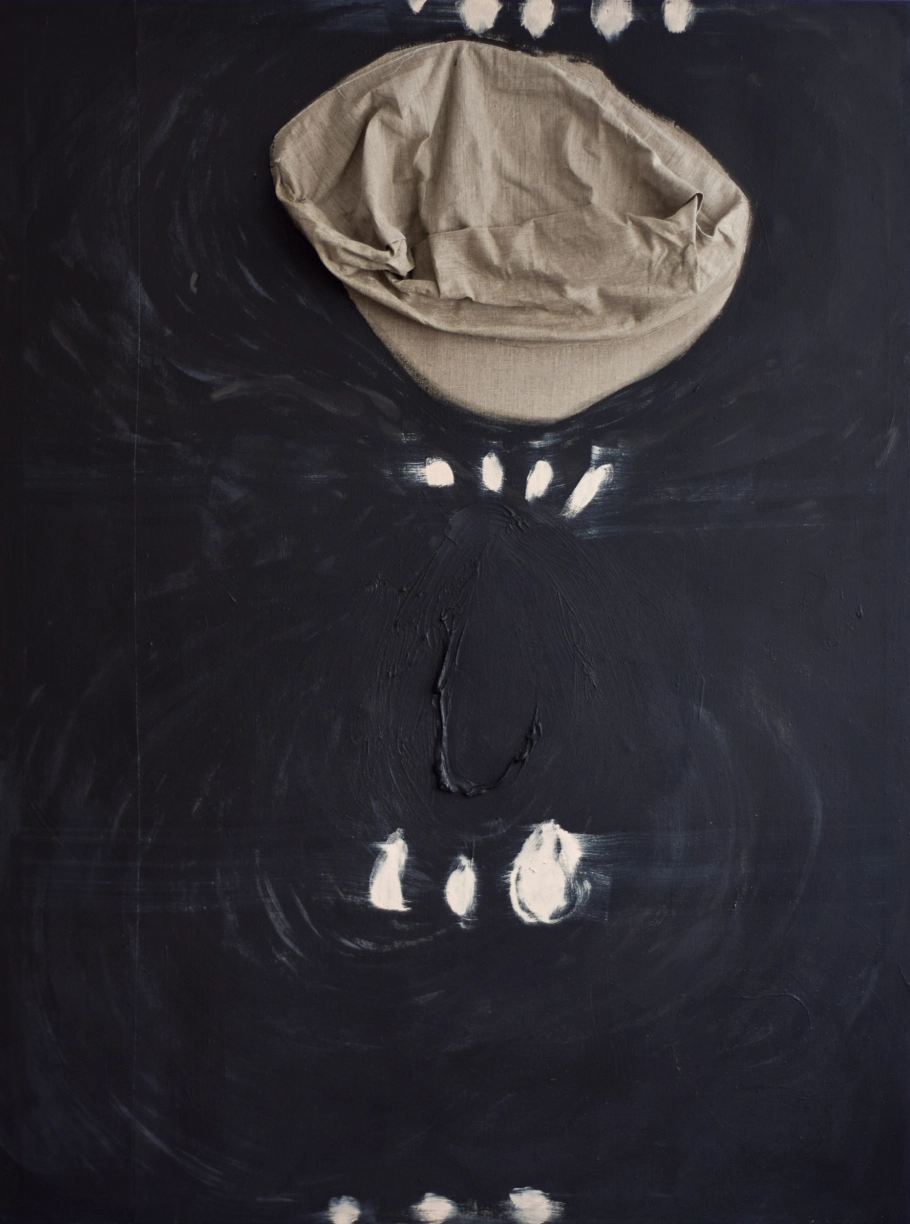

Yes, I now have quite a clear vision of what I want to do, but of course, it still is and will be evolving. For example, today I think I finally decided on the title of the exhibition. It might change, but I have a sense of direction, an approximation of a goal I want to go towards. I’m already building these works – “Propaganda from Nature” and “Gold is ashes (on my feet, on your feet) n°1”– which you may see behind me “Propaganda from Nature”. I’m sure that some of them will come to STRABAG. They’re quite complex in the sense that they have a lot of layers and are constructed from a wide variety of components.

It’s interesting that you referred to your painting process as “building”. Can you tell me more about the layers and the materials that you incorporate in your work?

„Building” best describes what I do. Some materials that I use need to dry and this takes time. I use a lot of layers of paint in my work, but I also use transparent paper, – when you cover it with water or a medium, it becomes translucent, shiny, almost opal-like – and elements made of melted, reshaped plastic. I also apply water-based glue: I dry its surface and blow air inside, it’s transparent, you can see through it. It creates a pocket, a pouch, like the ones I make of fabric – they’re in dialogue with each other. The shape of the fabric – apart from the obvious associations – may mean a lot of different things to different people. So the title of my upcoming show – I prefer not to disclose it yet – will connect nature, femininity, wisdom, power, and an alternative, counter-patriarchal definition of energy. In my work I wish to point towards this different way of relating to the world, which is completely lost at the present moment. And I think it’s one of the reasons why we are living in such catastrophic times.

Can you tell me more about how you define nature for yourself? We humans tend to project our way of thinking onto things, nature included, so I wonder how do you imagine the “nature of nature” so to say? What is its modus operandi, what goals does it have?

I think about it from the perspective of a person coming from Finland. I grew up in a small village, next to massive forests. And I think it left a mark on me. I really feel nature is way bigger than us, unimaginably bigger. It’s not something you can contain in a national park, it’s something so immense. It can be terrifying as well. Even though nature is often romanticized, for me personally, it’s very raw, brutal: survival is paramount.

I’m not a religious person, but I did entertain the idea of nature being some sort of a God. I have a lot of appreciation for nature, and I think in general, humans need to be more respectful towards it. We tend to see it as a resource, and it’s acceptable to take from it without any reciprocation. My cultural heritage is Karelia. This is an old culture, where especially elderly women were contacting nature, spirits of dead ancestors, through singing and poetry. And this view of nature is very close to me, the fact that there’s a visible and invisible aspect of it.

About the visible and invisible: I have a sense that you work very much like a medium. When you choose the materials for your works, by bringing them to the studio, you detach them from their natural environment, or context, and free them from the burden of reality, the need to be useful in a very concrete way. And then — through listening to them and determining their true character — you give them a new purpose, a new future. I’m wondering if you can see yourself in this reading. I am curious about how you discern the inner nature of the material you use, from a projection, where what is inside is misunderstood as coming from the outside?

Already at the stage of selecting the material, color, paint, anything really, I use a lot of intuition and select what is resonating with my mental image of a future painting. Like this wood glue I mentioned: it’s used to connect wood pieces, but then I take it to my studio and it’s not wood glue anymore: it becomes an instrument through which I say what I want to say. There are purely sensual qualities of the material that I appreciate – the touch, the smell of raw linen. It’s a very fleeting quality I would like to bring forth, like air or water, things that are hard to grasp.

And then of course, the next stages of the process have very intuitive, unconscious parts. It continues on its own without my help or control: I normally have some kind of obsession going and I follow it, I let it be in charge. And intuition is the reason why I select certain materials, why I work the way I do. I draw and write constantly. I do it every day, and I think this is what makes my thinking clearer. This way you dispose of a lot of mess that clutters your mind, so it emerges purified.

I suppose it requires a lot of faith in oneself and the creative process. But from what you said, this is also hard work, right? I mean, in order to gain this insight, this trust towards yourself, you have to strive hard towards knowing yourself.

And there’s a lot of failure involved too, constantly. There are days when things don’t work out. It’s unrealistic to expect that everything always goes well. There’s a lot of times I struggle with the work, where I am stuck solving one problem. Sometimes my writing is not making any sense and I feel I’m at a standstill with my drawings. But not giving in and working constantly is key. Even if my progress is slow, I still try. And I usually overcome my impasse. Things start flowing again. You encounter new problems and overcome them continuously.

Do you have a fixed work schedule?

I usually wake up quite early, at 7 am, and I start working almost immediately, at 8 am. First, I’m going through emails and then I draw and write – mornings seem the best time for this. And then I paint, which I continue as long as there is daylight. I’d say I work quite a lot, but I try to rest to balance it out: it’s crucial for artists to take care of themselves.

One more question about nature, related to the need for rest and our bodily limitations. I’m wondering how you define yourself as an element of nature, having in mind the definition you brought up earlier? What’s the part in you that you can also find in nature?

I feel my nature is my calling, the thing I’m called to do. In my case it’s making art. And then, of course, a bit more simple way to answer this question is to say that I am a part of nature, because I’m here now and one day I’m not. That’s why it’s important to enjoy the time we have. I think life and death are something that binds us to nature to a great extent.

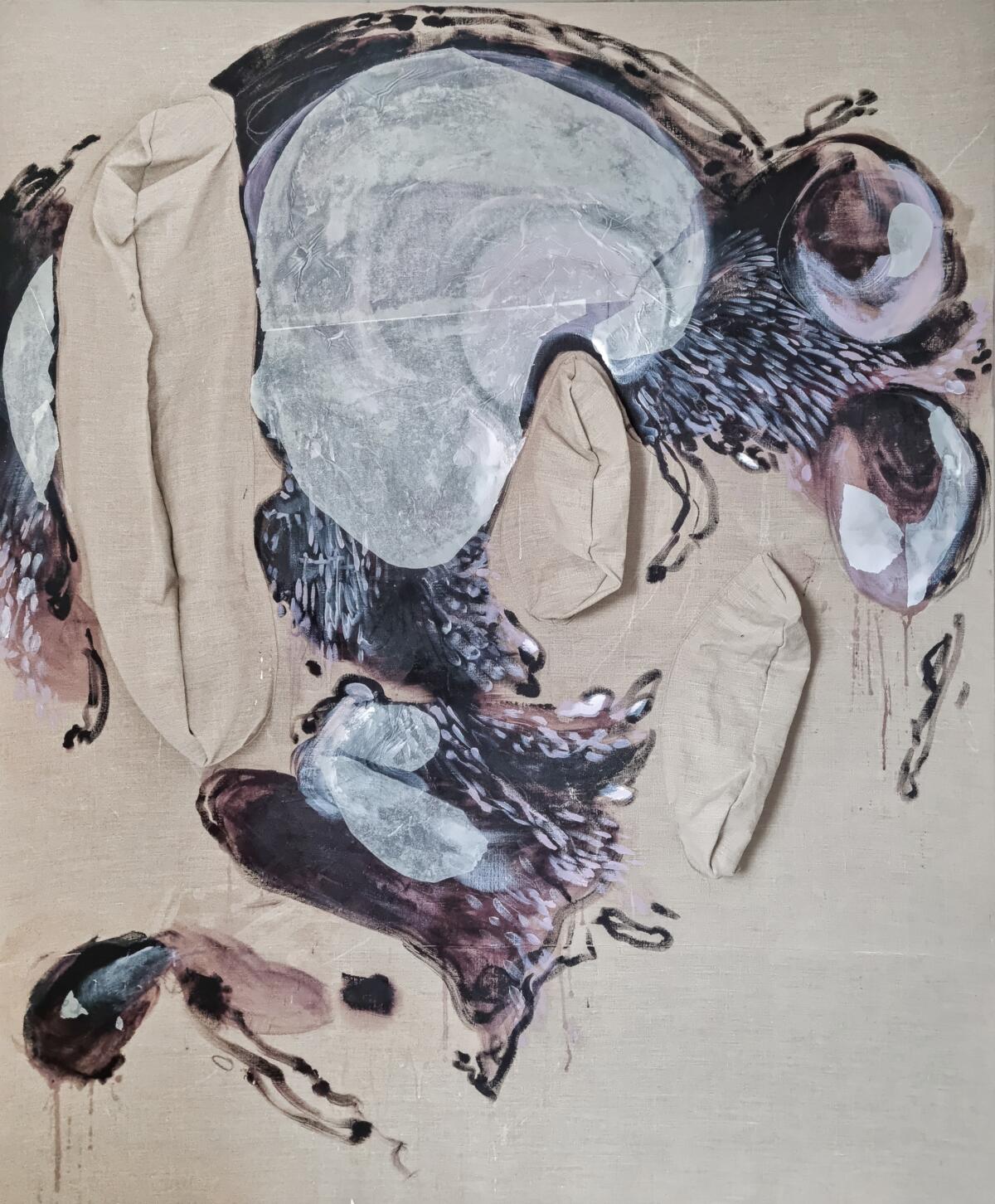

I suppose this connection can be observed in „Birth after Death”, one of your works from 2021. It’s a beautiful piece: the cold pink fleshy impastos set against gray and blueish patches of paint, at times resemble a wintery landscape and the next moment a fungi-like organism.

Obviously, the work is about biorhythms and the process of entropy. But I also wanted to emphasize that nothing goes to waste – including what’s left of you. In my paintings I deliberately hint at the idea that since we can clearly see the cycle of life operating within the realms of plants and animals, we can assume that we, humans, are also subject to this cycle.

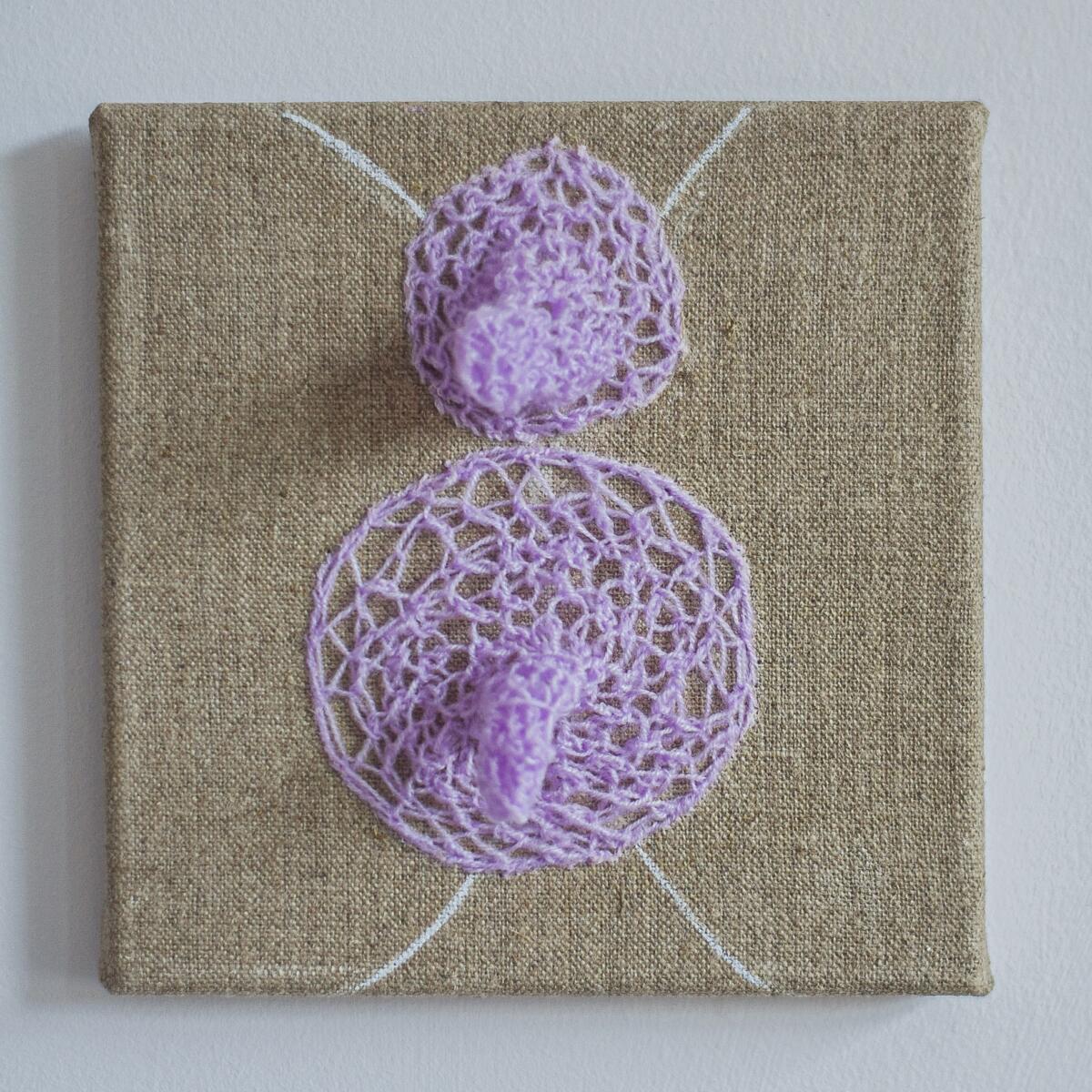

This cold pinkish, almost lilac tone pops up quite often in your work, right? „Mammal anatomy” – a tiny canvas adorned with a crocheted, nipple-like ornament – is a good example of this.

Yes, this one I made in Paris last summer, during the Cité Internationale des Arts residency. It was actually my brother’s child, a 5-year-old, who came up with the title. He had just learned how to identify a mammal: it’s an animal that has a nipple. Simple as that. For me, the lilac color is a metaphor for how we, humans, are part of the environment, a larger, heterogeneous structure. It’s not the shade of human flesh, it’s colder, it feels a bit off, like something between organic and inorganic.

This might relate to your “World Eggs” ceramic series you started in 2020. When I saw the images of the eggs exhibited in a large number at Art_Inkubator in Łódź, it made me think about the almost endless set of possibilities within the limitation of medium and size you chose for the objects, and the core shape that is repeated. And of course, this notion of birth and rebirth is encapsulated by and in the egg. When I look at your paintings, I imagine them as being depictions of the inside of these egg-shaped vessels, like if the world that you created on the paintings’ surface is somehow bent and enclosed in this globular form.

The theme of death and birth constantly reemerges in my work, but in the „World Eggs” series I am referring to the story of how the world is born according to Finnish mythology. We have this national epos – originated in Karelia – called „Kalevala”. It played a significant role in our culture. And in this story, the world emerged from seven eggs. This is what I enjoy in both painting and ceramics: observing the chemical reactions between various substances and media, watching the opportunities these interactions can generate; I have this tremendous need to test things. For the “World Eggs”, I made my own glaze mix and experimented with the glazes a lot. And sometimes I joke that if I weren’t an artist, maybe I would be a chemist.

I think this series may be a way to bring hope to myself. I’m very worried about climate change and the condition of our environment. In Northern Europe the temperatures are increasingly extreme. During the winter: -30 °C, -35 °C, summers are extraordinarily hot, like 35 °C. You can also notice how many animals have disappeared. There’s less birds, there’s less bugs, less everything. Nature in general is suffering. Maybe this theme of birth – the thought that maybe something new will rise out of this crisis – helps me cope.

The ceramic eggs in the series have always had the same core shape, resembling dinosaur eggs. Did you have a particular type of egg in mind when you were designing the mold?

I didn’t have a particular reference in mind when designing the mold. The first egg was done by hand. The height, the weight, they felt right in my palm. So it’s my own shape in every sense of the word.

The relationship between your body and the first egg seems almost demiurgic to me. I think I now understand the connection between this series and a hope for a better world.

I think many artists occupy a similar demiurgic position, in the sense that you can create whatever you want. There’s no limitation to that. I think that’s a part of being an artist, a part of art. And it’s the best thing about it.

And how do you think about your work’s influence on the world, its agency? Do you imagine a concrete purpose for it?

No, it’s not what I’m trying to achieve. But through art you yourself change; I think it helps me become myself more. And simply being yourself is already quite a radical thing to achieve. And it’s very inspiring to just be yourself. Of course it can cause tensions, frictions. But sometimes it may evolve into a community. But for sure, it’s something revolutionary.

I imagined that the agency of your work is somehow connected to healing.

It is, it’s related to my Karelian heritage. Some of my family members were these poet singers and their role was to heal. They went from house to house and sang people’s pain away. And the Keralian language – its structure and vocabulary – was specifically connected to this practice. The language disappeared when the Winter War – a war between Finland and Russia – started in 1939. Then Karelia was split in half; since then one half is in Russia, the other in Finland. My family lived on the side that now belongs to Russia, and they needed to escape the war. When the Karelians came to Finland, they had to cope with stigma; since the Karelian language sounded similar to Russian, and because of the war, people hated Russians. So then my grandmothers stopped using the language. My parents and I, we don’t speak Karelian anymore. But now the war trauma has been worked through to a certain degree and people are starting to learn Karelian once more. And perhaps Karelian culture can reemerge: I believe if you don’t know your cultural roots, they have been hidden from you, stolen or destroyed, it can break you; damage even entire generations. I was thinking about what part of this knowledge of my grandmothers can still be left in me. Do I carry something like this as well? Could I somehow follow my cultural legacy, even though it’s very much gone already? Perhaps my belief in the healing property of art is what connects me to my past.

And do you plan to learn Karelian as well?

For sure, it’s one of my dreams. But right now I’m learning German. It’s already my seventh language after Finnish, English, some Swedish, Spanish, and French. So it’s weird that I ended up picking up so many languages, and I’m not even very good at learning them, because I have dyslexia!

But you mix them quite confidently in the titles of your works!

I do, for example, „La evolution” is part French, part English. It’s interesting to think of “evolution” as feminine, how you expect things to be born from a female gendered body and so on. Whenever I notice something useful in a language, an expression or a fragment that fits my work, I use it without much hesitation.

But when do the titles come up? At the very end of the work, when you’re done with a painting, or do you have it in the back of your mind during the painting process?

I have two ways to approach this. I either have one title under which I will make a series and add numbers. When I work under one title it’s almost as if I’m editing a film. It becomes a theme, a subject and the subsequent pieces in the series are materializations of what I can say on that particular subject. But the title usually doesn’t come to me during painting. It’s a parallel process, it may take weeks, months. Titles have a very big role to play in viewing an abstract work, so it takes time, one has to be very careful.

I would love to learn more about the series entitled “I Ate the Honey Honeybirds Collected”. It’s a very narrative title when compared with your other ones.

This title is sourced from a book by Mika Waltari, a Finnish writer, author of „Sinuhe the Egyptian”. He had an extensive knowledge of the culture, but had never been to Egypt. The book is set in antiquity and Sinhue, the main fictional protagonist – among other historic ones like the pharaohs Amenhotep III, Echnaton, Tutankhamon, and Queen Nefertiti – retells the story of his life and how his biography entwines with the history of the nation and its rulers. And there’s a sentence when he describes a meeting between members of two very distinct civilizations. One gives an account of how he and his fellow countrymen keep birds and eat the eggs they lay. And then the other one describes his home, where birds collect honey and the residents of this country eat the honey the animals gathered. This dialogue shows how something that sounds very weird – nonsensical even – to one person, can be the other person’s reality. And yet they have to inhabit the same time and come together on the same ground. Just like the many different materials and shapes that meet on a single plane of a canvas.

Do you already feel the difference in how the world is structured differently through different languages?

Yes, definitely. I think it has very much to do with how people are. And even based on self-observation, I can relate to the research stating that your personality changes depending on the language you speak. Even your body expressions can be different. And surely, as a Finnish native speaker I change when I switch to English. In Finnish I’m more poetic I think; I tend to go around things. It’s great to know the language, for me it implies a unique way of being open to somebody else’s experience.

You picked up several languages, did you by any chance discover some unique characteristics of the Finnish language? You said that you’re a more poetic person when you speak Finnish, but how does it relate to the other languages that you know? My native language is Polish and for me, Polish when compared to English for example, is a more contemplative, passive language. There’s a lot of adjectives. I feel that English is more focused on verbs and action. How would you personally define the specificity of the Finnish language?

This is my feeling as well, Finnish has a lot more adjectives when compared to other languages I learned. Maybe I can describe things better in Finnish than in English, but I feel like in English there’s just not enough words. It’s lacking some expressions. And just the way you speak Finnish is poetic. But the most significant thing is that we don’t have a gender in our language. We don’t have a „she” or „he” referring to anything. You approach a being without this burden of gender-related presuppositions. And this is something I think is interesting and creates a different relationship, perhaps a more humble one, for both humans and non-humans. It’s weird to me to observe how gendered the world is, because in my mother language it’s not. And you start to see it as one of the many ways to describe the reality around you: a possibility, not a necessity.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Jósefina Alanko |

| Place / venue | STRABAG Artaward International |

| Website | www.strabag-kunstforum.at/home-en/ |

| Index | Ewa Borysiewicz Jósefina Alanko STRABAG Artaward International STRABAG Kunstforum |