The Best and Worst of Art in Central Europe in 2019

Karina Kottová and Piotr Sikora (Czech Republic)

Not so boring anymore

The year 2019 on the Czech art scene was with no doubt one of the most turbulent in the recent half of a decade. While new institutional and artistic modes of operations were in progress, the process of dismantling the old order couldn’t be carried out without conflict. In this rough time, the ideal of kinship has been largely preached but mostly exercised within separate groups allied through a shared understanding of the world and one suggested approach to it. The year was dominated by protesting, cancelling, firing, fighting, but also accepting, attempting, reassembling. The artistic milieu was truly all but boring.

Fight for the National Gallery

In spring 2019, the director of the National Gallery Jiří Fajt was dismissed from his office by Minister of Culture. Supposedly for economical reasons, the most outstanding of which was a self-approved contract for a high financial bonus. Directors of international art institutions reacted immediately in a letter addressed to the Minister in support of Fajt, in which they were indicating his achievements. Similar support was received from within the Czech scene, but here the paths have already begun to diverge. The more critical locals were quite aware of the real nature of affair at the National Gallery, which certainly could not be judged from the pimped-up exhibition photos. Rather than defending Fajt, the more radical fraction opposed the way the director was dismissed, in fear of further political interventions in the cultural milieu to come.

Finally, the minister resigned, and a second temporary director of the National Gallery is already in place, resorting to rather not temporary measures – such as dismissing the former chief curator Adam Budak. The competition for the new director should be announced soon, while hopes for the long-awaited transformation of the institution remain rather moderate.

Dollarz Euroz Jenniez

The discussion on the ethics of financing art entitled “Money, or Life?” initiated by the Feminist Art institutions in collaboration with Artalk.cz and Artyčok.tv, which took place in the fall, was definitely one of the most thought-provoking talks, that Prague’s art scene encountered last year. Everyone seemed to be quite pleased with the fact that different fractions could finally meet to critically assess and happily agree and disagree on things they did not remember exactly afterwards, as no one dared to record the event.

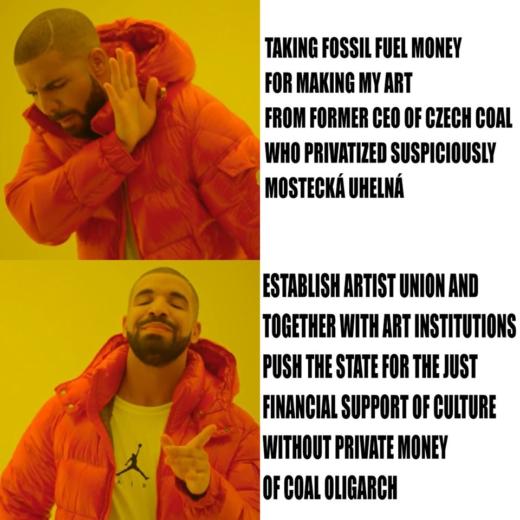

studio without master https://www.facebook.com/Atelierbezvedouciho/

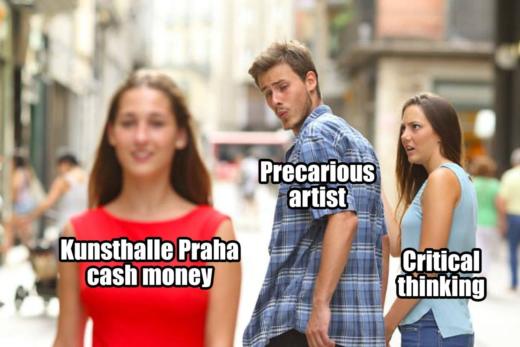

The atmosphere of discussion was significantly escalated by the fact that private investors with problematic backgrounds recently proceeded from collecting art towards exhibiting it in newly established institutions. The opening of Kunsthalle Praha, founded by the family foundation of a former coal baron, gave impetus to a re-evaluation of what does the term “artwashing” mean in Central and Eastern Europe. Another impulse was the launch of the Telegraph Gallery in Olomouc, based on the resources obtained from the bailiff’s business of itsner as well as the large art collector Robert Runták.

Questioning the ethics of feeding art with wealth made on poverty or fossil fuels also reanimated the debate about the already long-standing banks and their controversial policy. To sum up, the general impression could be demonstrated with a brilliant quote by the theoretician and curator Hana Janečková: “If you want to support art, close down your dirty businesses and give us your money!”

studio without masterhttps://www.facebook.com/Atelierbezvedouciho/

Protesting hard

Writing open letters, dropping, grumbling, revolting before the Ministry of Culture, on Letná park, or at significant coal-fueled plants became a regular activity of many.

Every month a different type of protest was organized, some of which were quite successful, and some fairy contra. The most recent letter was in defense of Adam Budak, as the manner in which he had been dismissed left rather bitter impression. With another note, the rector of the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design was addressed. The reason of this protest was disregarding the choice of the open call board of trustees to select artists Julie Béna and Markéta Magidová as the new chiefs of the Intermedia studio, after self- igniting head of the studio Jiří David.

“Today I feel a bit like this girl, the one that you fuck but that you don’t really want to introduce to your family“ – as Béna stated. The artists Sláva Sobotovičová and David Fesl were cancelled hard after a performative ceremony for the Věra Jirousová Award for art critics. The corresponding anti-awards accent slipped from good satire to unfortunate insensitivity when the category “Whiner of the Year” quoted Facebook statuses of artists or curators who shared conflicting personal experiences, such as assault.

The whole debate about artwashing debate created quite a fruitful context for artistic responses, from the uninvited “wild 90s” opening event at the Kunsthalle Praha, through wrapping Telegraph Gallery with execution stickers, to creating a website mocking the J&T Bank Art Index. The only protests everyone seemed to be joining were those against our beloved prime minister, “the purest lily” Andrej Babiš.

You cannot hide dirty money behind a painting protesting Telegraf Gallery funded by bailiff business

Gestures of Solidarity

Despite all the struggles, we must point out at least a few things that triggered more sensitive kind of emotions. One of the best events we had the pleasure to participate last year was WOODS. Community for Cultivation, Theory and Art, a small-scale symposium at the edge of a forest in Orlické Mountains, organized by the Institute of Anxiety.

A part of the forest was bought by the organizers in order to restore its natural biosphere. The accompanying symposium not only theorized the perspectives of the (decolonized) nature, but also allowed its participants to socialize with the environment and with each other in a way the urban creatures rarely encounter.

photo. Stan Baranski 2019 @ WOODS. Community for Cultivation, Theory and Art

Another moving event was carried out by the artist Magdalena Kwiatkowka, who created a temporary shelter for female and transgender homeless within INI Project, entitled Magdalena’s Laundry after Irist facilities for maladjusted women. She turned the project space into a place for gathering, cooking, organizing workshops for the public, and celebrating Christmas.

Andreas Gajdošík, winner of the last edition of the Jindřich Chalupecký Award, decided to renounce the residency in New York to avoid flying, and offered himself to share both his monetary award and residency with all the nominees. The gesture sadly had a bitter aftertaste caused by the inscription on his T-shirt, which boldly offended Sláva and David, which he mentioned earlier. The year was certainly not boring, nor was it black and white.

Supposedly exceptional shows that we’ve missed in 2019

Piotr Sikora:

– Treat Me Like Trash, Cause That’s All I Am by Adrian Altman at SPZ Gallery in Prague

– Work on The Future by Pavla Sceranková and Dušan Zahoranský at FAIT Gallery in Brno

– Jindřich Chalupecký Award 2019 at the Moravian Gallery in Brno

Karina Kottová:

– Loop Infinity Down to Side by Markéta Magidová at Futura in Prague

– Marie Lukáčová: Moréna Rex & Jiří Žák: The Incantation of the Real at the CCA Prague

– Isotonic Songs by Pavel Příkaský a Miroslava Večeřová at Fotograf Gallery in Prague

Exhibition we really, really liked in 2019

– Horse and Britches by Julie Béna and Romana Drdová at Drdova Gallery in Prague

– Drop Dead Funny at House of Arts in Brno

– Eva Kmentová: Woman in the Sun & Eva Koťátková: Woman in a Box at Hunt Kastner Gallery in Prague

– Installation For a Theatre on Mars by Than Hussein Clark in collaboration with CPWH at Plato Ostrava

– Distress Over Parliament at Lítost Gallery in Prague

Anna Karpenko (Belarus)

In November 2010, the collective exhibition “Opening the Door? Belarusian Art Today” was opened at Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius, representing the works of Belarusian artists living abroad (Marina Naprushkina, Aleksander Komarov, Lena Davidovich, Maxim Tyminko, Oleg Yushko, Oxana Gurinovich and others).

In the introductory article to its catalog, Kęstutis Kuizinas, the director of the Lithuanian Center for Contemporary Art, who was the curator of the exhibition, left the question “Are the doors to the contemporary Belarusian art really opening?” un-answered. Similarly the questions about its actual existence were suspended, as well as the answer for the question: why this inconsistent Belarusian art community with some of its members living outside Belarus and others remaining in the country, was so careful and straight in articulating socio-political statements.

December 2010 left no doubt about the answer to the question about the readiness of the Belarusian community to make political compromises. On December 19, 2010, thousands of people came to the central square in Minsk to protest against the results of the “next” “fair” presidential elections in Belarus. The protest was brutally dispersed. Hundreds of people were imposed administrative and criminal penalties, were beaten and dismissed from their jobs.

In 2011, the exhibition “Opening the Door? Belarusian Art Today” was opened at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw. It presented the works of contemporary Belarusian artists, which cannot be shown in any Belarusian state art institutions.

The list of contemporary Belarusian artists whose works I would like to mention in the following text is very subjective. It contains the names of those who may not be so well known in Poland, Lithuania, Germany and other European states, unlike other Belarusian artists who have long been living outside the country. Moreover, I also wanted to mention collective exhibition projects which would allow to better understand topics and problems that are currently being dealt with by the Belarusian “inner” field of art.

Jura Shust NEOPHYTE/Solo Show

7-29 November 2019

«Ў» Gallery of Contemporary Art (Minsk, Belarus)

The “Neophyte” project of the artist, designer, graphic artist and researcher Jura Shusta looked like an enchanted acid forest – a place where, according to Belarusian traditional culture, one had to look for a magic fern flower that would guarantee its owner happiness and happiness.

In the present context, these searches relate to hunting drug hideouts. Article 328 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus provides for an excessive penalty for trafficking in narcotic and psychotropic substances, but in most cases punishing adolescents and young people, and not the main figures responsible for the entire industry. Over the past few years, the “Mothers-328” movement has been active in Belarus aiming at improving legislation and combating real drug trafficking.

In 2019, Shust signed an exclusive contract with “Fragment Gallery” (Moscow).

Vitebsk artist Kirill Demchev can be described as the most consistent young avant-garde apologist in Belarus. His project “Nevidivism”, which is defined by the artist himself as a stage that follows Malevich’s Suprematism, was perhaps the only project of institutional and art criticism carried out in Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art. (for more details, see A.Stebur’s article on http://statusproject.net/en/stebur-diomchev/ )

In 2018, after the official opening of Museum of the History of the Vitebsk Folk Art School, associated with UNOVIS movement (ironically, established in Marc Chagall Street), it became institutionally inviolable and closed to politically unreliable experiments. Avant-garde ideas, raised in the 1920s in the midst of protests and free expression, were enclosed in a linear exposition with the museum turning into a mummy, in every possible way protecting and isolating itself from contemporary art.

Kirill tried to fight this mummification. However, the artist did not manage to hold his performance in Museum of the History of the Vitebsk Folk Art School, he was given a more neutral space of the Contemporary Art Center at Lenin Street instead.

Incredible transformations of Suprematism in today’s Belarusian realities were also shown by Maxim Shved in his film “Pure Art”. A graduate of A. Wajda School of Film Directing, Maksim, together with the artist Zakhar Kudzin and Łukasz Czajka explores the unique phenomenon of “housing associations art”. Every day, Belarusian public utilities employees walk around the city with buckets of paint covering any political slogans, tags and forbidden national symbols with suprematist squares. The film trailer is available on http://listapad.com/programm/natsionalnyy-konkurs/dokumentalnoe-kino/pure-art/

The issue of horizontal interaction and institutional criticism is addressed not only in individual artwork, but also in entire projects and spaces, such as, for example, “The Shed” by the Brest artist and curator Volha Maslouskaya – widely known in Poland as a member of “Bergamot” collective. In 2017, on the territory of her private house and backyard, Olga made her old and dilapidated barn open to the public as a space where contemporary art in its most diverse forms could be exhibited without being subject to risk of censorship. The condition of the barn keeps deteriorating over the years, its roof leaks and no one repairs, reconstructs or patches it. The shed can be compared to contemporary Belarusian art, which often develops in parallel and opposition to state programs intended only for exposing “the only legitimate”type of art.

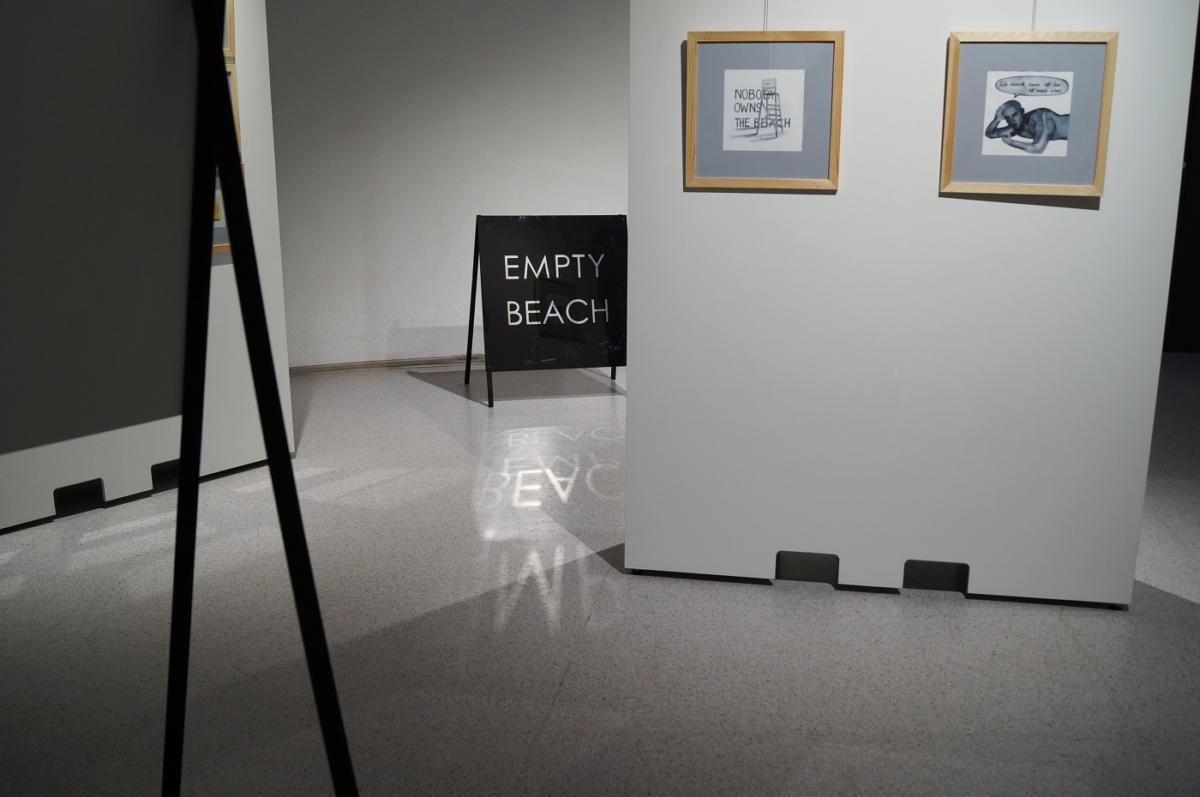

The issue of right to self-expression and free movement of one’s body and physicality beyond all borders is critically interpreted in the solo exhibition project “Closer, than Paradise” by the young Belarusian artist Alesia Zhitkevich. For decades a famous nudist beach around the so-called Minsk Sea has enjoyed a reputation of a holiday destination not only for nudists, but also for all free-mind people. However, since it was regularly supervised by local police during last year and people relaxing there scattered, it was eventually closed.

The confrontation of the state with sexuality, the physical and the political, invisible violence and the right to freedom, people in iron helmets armed with batons and naked vulnerable bodies is ironically expressed in the slogan “Attention! Nudist beach”.

One more representative of the young cohort of contemporary Belarusian artists is Uladzimir Hramovich, who implemented several projects in 2019. One of them was made in a form rare for the local context – a tribute to an artist of the past generation. The project supposed interaction with the graphic artist Gennady Grak. The exhibition, entitled “Follow the White-Black Line”, showed linocut and graphics of this classic representative of the Belarusian graphic school, who found himself in a marginal position with his works not shown by the state institutions for many years.

Also noteworthy was the individual project of activist Uladzimir Hramowicz related to his official status as a “cultural worker”. In 2015, the President of the Republic of Belarus signed the so-called Decree On Preventing Social Dependence (later called the “Parasites Law”) obliging jobless citizens to pay a tax.

Almost all the representatives of culture not officially employed by state institutions (from film directors and writers to artists and curators) were included in this category. In 2018, after having received a corresponding letter informing him of his status of “parasite”, Uladzimir Hramovich decided to directly contact the Ministry of Culture with a request of granting him the status of “an artist”.

Hramovich’s socio-artistic gesture significantly commented on actual working conditions of people involved in art and culture in Belarus.

The issue of precarious work and working conditions and tension between “creative class” and “real economy” was also a main point of Michail Gulin project “Social role” when the artist offered the audience to try on real clothes and attributes of workers on Kastrychnickaja street – a place which has become a space gathering people from creative industries (“Hipster strasse”) scrubbing all traces of former plants.

“Work Hard. Play Hard” is a long-lasting international horizontal art project that provides a rare example of the issue of creative work in the conditions of current market and new forms of collective practice becoming not only an object of criticism, but also a way of existence http://workhardplay.pw/en/about.html

According to the ideological originators of the project: “Work hard. Play Hard “is a collective self-organizing platform dealing with issues of knowledge production, cooperation, work, leisure, technology and acceleration through various performative, participatory and discursive formats.

The four permanent members of the working group Olia Sosnovskaya, Dina Zhuk, Nikolai Spesivtsev and Aleksei Borisionok strongly emphasize that they are neither its authors nor organizers, because since 2016, the “authors” of the project are everyone who joins a series of different practices and events from collective meditations to analytic discussions and readings held within one week.

This is a rare example of self-organized collective practices localized in Belarus and bringing together an international art community.

An example of another project carried out beyond institutional boundaries is the international photography festival “The Month of Photography in Minsk” (www.mfm.by ), initiated in 2014 by the Belarusian photographer Andrei Liankevich. In 2019, it was dedicated to major historical transformations. This year’s curator Antonina Stebur divided the conceptual part of the exhibition into three categories: social choreography addressing the way physicality as a social category manifests itself in historical narratives (the famous project of the Lithuanian photographer Romualdas Požerskis “The Baltic Way” shown at the festival provided a vivid illustration of this phenomena); history re/deconstruction and gaps. For the first time in the framework of the festival, a portfolio review was held with such experts as Krzysztof Candrowicz, Simon Menner, Arnis Balcus, Emmanuelle Halkin, Clara Chalou and Olga Bubich taking part in it as reviewers.

In May 2019 at Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art “The Beyonders. Other Histories of Belarusian Art” (curated by Sophia Sadovskaya and Anna Karpenko) exhibition was presented to the public. The exhibition was the result of 1-year’s research of the state of contemporary “outsiders art” in Belarus and was for the first time featuring Viktor Kruglyansky’s collection – the only one in Belarus elaborated by the psychiatrist. From 1962 to 1998 he was collecting the works made by patients of the psychiatric clinic, among whom the names of famous Belarusian artists appeared.

I would like to finish this list with the project “Social Marble” created by the Belarusian artist Sergey Shabohin (currently based in Bialystok and well-known in Poland) in partnership with the philosopher Olga Shparaga and “tranzit.at” http://at.tranzit.org. The installation, first shown in Minsk and then in Berlin, updated the issue of social mythology, while evolving in two directions: as socialist myths, rooted in Belarus, and democratic myths, which turn out to be a self-adhesive film imitating marble – contrasting with the social material of marble of the past era.

I am writing this text in December 2019 in Minsk and the streets of the city are again crowded with active Belarusians protesting against the forcible “deep” integration of Belarus with Russia, which threatens to actually absorb the independence of the state through the creation of the so-called supranational organs, the single currency, etc.

In the early 2000s-2010s, the independent Belarusian art community was active and open in expressing its views on socio-political issues, which could be seen at the above-mentioned exposition “Opening the Door? Belarusian Art Today”. Are we ready for open and radical art and civic statements today? The question remains open, just like the one posed by the Lithuanian curator Kęstutis Kuizinas in 2011, “Are the doors really opening”? or maybe they are closing forever…

Marina Oprea (Romania)

In the last year of the decade, the Romanian art scene fought more than ever for its survival. With reputable art initiatives having to abandon their headquarters and become nomad due to evictions or lack of funds, the sense of local uncertainty seems only to deepen.

The community seems more fragmented than ever, with everyone being too self-sufficient to notice this lack of continuity in the implementation of independent artistic initiatives. But not everyone has lost hope of finding more efficient and lasting solutions that can change the community for the better. And amid all the bad, there are still people and projects worth celebrating.

The Ministry of Culture doesn’t know the first thing about culture

Artistic protest in front of the Ministry of Finance

Since its establishment in 2005, the National Culture Fund Administration has funded thousands of initiatives throughout Romania and has become their only source of income for many. However, in 2019, the main source of funding for most of the independent sector lost 30% of their annual budget, turning over 70 cultural projects adrift. Many expressed their outrage via artistic protests in theaters and cinemas throughout the country, with artists like Dan Perjovschi and Suzana Dan forming a resistance group that aims to come up with some kind of counter measures for situations like this. A meeting with the minister revealed what we already knew: the state couldn’t care less about the current cultural climate and the hardships of cultural workers.

Nevertheless, for many of us this served as a wake-up call, demonstrating once and for all that this NGO based program for receiving funding is not only extremely hard to navigate due to the intricate bureaucratic demands but also does not allow entities to make any kind of profit. Moreover, the AFCN could cease to exist at any moment, demanding for a more viable alternative and, above all, working together.

The end of an era: The Paintbrush Factory is officially closing

Formerly known as the most spectacular art center in Romania, hosting up to 29 spaces for galleries, artist studios and dance and theater halls, The Paintbrush Factory is sadly closing down exactly 10 years after it first opened. Some say it was inevitable: years ago, a major rift between the organizers divided the once renowned center into two separate entities that did not get along at all. Since then the building itself has been slowly emptied out and taken over by office spaces, thus returning to its default function of a factory. Yet the artists and galleries that called the factory their home are hopeful and are determined to see this end as a new beginning.

Adrian Ganea the rising star of digital art

Adrian Ganea ‘If a tree were to fall’

In recent years a new generation of artists based in Cluj is on the rise, interested in new media arts and especially digital art, as a response to the ongoing local transformations and signs of a total shift of generations. Among the newcomers, Adrian Ganea stands out with his interesting new approach, mixing different mediums to showcase an incredible range of skills and perspectives. With a training in stage design, his works aim to enact the production of fiction, often reflecting on its increasing automation. His practice ranges from designing scenography to programing CG simulations and composing videos. Lately he’s been experimenting with creating AI environments and dancers that interact with real people performing live, which he has presented in several shows, locally and internationally, in 2019. The end of the decade has marked Romania’s interest for the newer trends in digital art, with initiatives like spam-index.com, a website for mapping Romanian artists that fall under the wide spectrum of digital practices, fore-fronted by Ganea and his peers. Adrian’s promising future ventures are worth keeping an eye on.

Art Encounters Biennial: a different approach

Timișoara was sure to prep up for its upcoming title as 2021 European of Capital Culture with a new approach to the Art Encounters Biennial, arguably the city’s most prolific contemporary art event. Instead of the usual four months of activities, 2019’s edition was extended to the entire year and to focus on the less visible actors of art production: curators, producers, scholars, teachers and students were all brought to the forefront. Beyond the usual (and quite good) gallery exhibitions, numerous sights in Timișoara hosted workshops, collective, screenings and, among other things, a curatorial school focused on building networks, which was also extended to Cluj-Napoca. The Biennial included artistic interventions around town, public tours and other commendable cultural endeavors. All these were possible with the help of many young volunteers who worked countless hours, often without training and guidance and with little pay. It’s about time that we also address what happens in the backstage of ample art events and acknowledge and properly reward the thankless work of volunteers.

Minitremu Art Camp: already practicing a better society

Minitremu Art Camp, photo. Monotremu

Here is a lovely initiative that should be applauded for its alternative and wholesome approach to art education. The brain-child of art group Monotremu (Laura Borotea and Gabriel Boldiș), the camp takes place each year at a different location, in the middle of nature, and is open to local and international teens with a passion for contemporary art. Some of Romania’s most important artists and curators are invited to hold workshops and pass down their knowledge and resources to future generations. At Minitremu, participants don’t just learn about art, but also about the importance of having the right mindset, building a community and looking out for each other. In turn, the invited guests can also glimpse new models of communication and fresh alternatives to old practices. Artworks produced by the Minitremu campers were later presented through various exhibitions, including one at the Art Encounters Biennial.

The Mihai Oroveanu collection

The Photographic Archive and history with a small h_ – An exhibition by Alexandra Croitoru Special guest – Cristina David, photo. Stefan Sava

In recent years Romania has seen an ever-increasing rise in attention towards archive studies, visual or otherwise, across all layers of contemporary artistic practice. One of the more notable such projects is The Photographic Archive and History: Memory and Research, with its starting point the vast photographic collection amassed over five decades by late art historian and curator Mihai Oroveanu, which offers rare glimpses into the country’s turbulent past. Initiated in 2018 by Salonul de Proiecte with the aid and input of Anca Oroveanu (the current holder of the archive), it was only in 2019 that the interdisciplinary and multi-layered approach made a greater impact. Preoccupied not only with the mere digitization of an important archive, this effort also included four successful art shows (three solo oriented shows in Bucharest and a student based collective show in Iași), along with public presentations and international colloquiums. Accompanying all these activities is the dedicated site for the Mihai Oroveanu Image Collection which functions as an effective research platform and dissemination source for a selection of images. That being said, it’s important to clarify the strong hold the collection has on the local artistic scene. Oroveanu’s passion for photography, both as a respected practitioner and collector, along with his unfortunately unrealized intention of setting up an institution dedicated towards the study and practice of the medium are well known. It’s understandable as such, in the eyes of the active photographic community especially, that the attention and care for such a relevant photographic archive, which was always known but never really available for exploration or study before, were long-due.

The allegedly stolen and auctioned works of Geta Bratescu

Geta Bratescu “Jeu des formes” 2009

After passing away in late 2018, The Grate Dame of Romanian conceptual art left behind an ample body of work which has unsurprisingly caught the imagination of the art market, sparking some controversy. Just last summer, the auction house Artmark, the largest in Romania, announced an auction event containing several works by Geta Bratescu that are allegedly stolen. Teodor Bratescu, the artist’s son, claimed he noticed the missing works back in 2017, but he chose not to call an investigation because he did not want to subject his mother to police inquiries and overall stress at that time. He did however notify the authorities once the works were up for sale, but this apparently led to nowhere. The auction was carried out as scheduled and Bratescu’s works were sold at a hefty price, with Artmark’s disclaimer that the origin of the items they sell is not their concern. Unfortunately, this disinterested attitude towards preserving the legacy of an artist is what ultimately leads to fragmented collections and important pieces that go undocumented and risk being lost forever.

Celebrating kinema ikon, the oldest artistic collective in Romania

Interventions – Electric Brother, Kinema Ikon at Rezidenta BRD Scena9, Photo. Vlad Catana

Speaking of longevity and legacies, on the bright side of things, kinema ikon is an art group that dates back from the 70s and is still dynamic and significant today. On the eve of their 50th anniversary, several exhibitions were organized around the country, with a prominent event in Bucharest, a 1970/2020 film retrospective curated by Călin Man, the group’s coordinator since the 90s. The exhibition hosted by Rezidența BRD Scena9 incorporated older re-contextualized cinematic works, fun interactive experiences with VR and mesmerizing installations. A variety of accompanying events took place correspondingly, including a workshop for children. kinema ikon, or ki, is the synonym for new media in Romania. Their extensive portfolio includes experimental cinema in the 1970s and 1980s, video art, new media in the 1990s, soundscapes, installations, post-internet art and everything else. Countless members of the group are artists, composers, graphic designers, architects, writers and people from different backgrounds who have united for one purpose: experimenting with the latest available technology. They are now scattered all over the country and abroad, but each member, old and new, is constantly contributing to the development of collective ki awareness.

Roma Futurism: Roma witches are gaining recognition and visibility through art

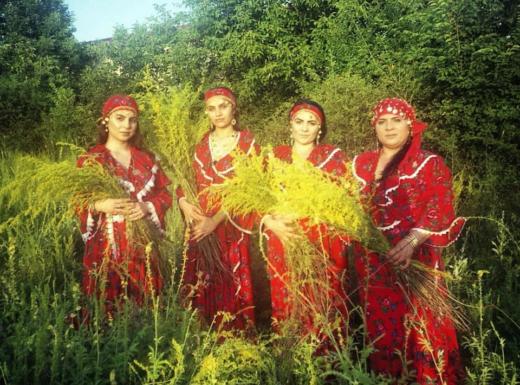

‘Roma Witches’ by Virginia Lupu

Mihaela Minca and her family have a long-standing tradition of witchcraft in their family that has been passed down from generation to generation. And now, with the help of artist Virginia Lupu who documented their lives for the past two years in an attempt to demystify magical and occult practices within the local context, the Roma witches have become prominent figures of the cultural scene, being fully embraced into the art world. In 2019, they held a two-day workshop in Bucharest where they made an incursion into their beliefs and practices. The Minca coven of witches (Mihaela, her daughters, Ana and Casandra, and her daughter-in-law, Beatrice) coupled with art theorist Valentina Iancu, Romani actress Mihaela Drăgan and Virginia Lupu shed light on the Romani magic crafts and discussed them in the broader context of feminist practices and Roma activism. In the current socio-political climate of nowadays, the rise of neofascism, the policy of forced evictions and displacements, anti-Romani manifestations, and increased vilification of Romani people in the face of the economic crisis has made the need for establishing Romani public voice more urgent than ever before. Roma women’s place in the world has been uncertain for centuries, and the endeavors like this one offer a platform for expressing the voices and experiences of the Romani people.

Ioana Păun takes political theater to new heights

‘153 seconds’ by Ioana Paun, Photo. Florin Bondrila

Playwright and activist Ioana Păun has been making documentary theater for years now and is known for her incisive and direct approach towards the subjects she chooses to discuss. In late 2018 she debuted a play entitled ‘153 seconds’, based on the memorable accident of fire that destroyed Colectiv club, in its wake in the autumn of 2015, bringing about many fatal victims. Taking on such a delicate subject was a bold yet successful attempt of Păun to elaborate the analysis of this tragedy and emphasize the significance of current social issues that contributed to its emergence. Based on survivors’ accounts, ‘153 seconds’ consists of a series of vignettes performed by a collective group of actors that revise the classic view on dramatic events by not establishing individual characters. The performers work in an ensemble and, with the use of energetic music, light effects and simple yet effective props, offering a dynamic, lucid and vivid view on the systematic socio-political problems that torment Romanian society. As ever, Păun’s shows are always penetrating, vigorous and thought-provoking. The play was presented during the tour around Romania in 2019 and has received favorable reviews, reviving older discussions and generating new ones. Nowadays, Ioana Păun is touring Europe with her latest work, The Birth of Violence, and one of her older pieces, Genetically Modified Organisms, as part of Europalia and The France-Romania Season.

Adomas Narkevičius (Lithuania)

It is difficult to see past the brilliant Sun & Sea trio Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė & Lina Lapelytė this year. And that is not because of the Venice Golden Lion and the subsequent accolades. Sun & Sea: Marina wasn’t as self-assured, didactic and totalising in its presentation as many other exhibits in Venice this year. Its slowly unfolding indeterminacy, quietness and sensitivity allowed life to actually seep into the work. There ‘life’ does not stand simply as an affirming, emancipatory, naive force. This could be read into it too, however, the poignancy of Sun & Sea was felt in little details: the artists’ children perform, coming in and out of their roles; a dog barks over everything; the performers are visibly tired while singing beautiful solos on endless fatigue; the artists themselves substitute the performers on the set. At times it felt as if all that was so unstable, that Sun & Sea might just break down just like… you know where this is going…any one of us, the market, the planet.

Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė & Lina Lapelytė’s opera-performance did not pretend to be impervious to the reality outside Marina Militare or detached from those who devised and performed it. And so, it stood out as a subtle, fragile yet powerful collective voice.

Curators

Artists taking matters into their own hands. Run by artists and/or independent spaces such as Editorial, Lokomotif, Monto’s Tattoo, Autarkia as well as one-off projects (public programs, exhibitions, conferences, reading groups, etc.) initiated by artists or cultural agents that do not define themselves as curators was definitely the most exciting part of Lithuanian art life in 2019. These self-initiated processes rendered the art scene lively and self-reflective despite institutional fatigue on one hand and on the other hand the lack of fresh curatorial voices, spaces and perspectives. Nevertheless, it can be argued that their contours were beginning to take shape in 2019. That gives hope that 2020 will bring about bolder curatorial gestures and consistently, coherently curated spaces.

Exhibition

‘XVII century’ group exhibition, curated by Laura Kaminskaitė and Robertas Narkus, Autarkia, Vilnius

Run by artist Robertas Narkus from its inception in late 2016, the so-called artist day-care centre Autarkia was known as the project space in Vilnius that does not really carry so many projects, at least, exhibition projects. This seemed partly due to the former canteen being not ideal for presenting artworks in the conventional format of an exhibition.

In that case, the ‘XVII century’ exhibition this Summer by artists Laura Kaminskaitė and Robertas Narkus certainly defied expectations, inviting over 60 artists from at least 3 different generations, exploring wildly different realms. It was a bold departure from the white-cube photogenic demands, distorting predictable constellations of artist names and dominant display modes, at least locally. It could also be read as a tongue-in-cheek response to multiple Lithuanian art institutions embarking on megalomaniac retrospective exhibitions this year.

It came to be a laid-back exhibition presenting the unusual or previously unseen works of known and also not so recognised figures. It did nudge the works together hence the spatial limitations. Nevertheless, physically crowded, they still left room for each other to breathe in. ‘XVII’ century’ disrupted prescriptive canonizing narratives, such as those of ‘the art of the present’; ‘of the past’; ‘signature style’ and half-truths about its own fitness or laziness as an ‘institution’ run by artists. And one can salute to that.

Venue

Kaunas Artists’ House is an example of an institution that is able to achieve so much even with limited resources with open-minded, professional leadership at the helm and a team of local activists, artists and educators coming together. It reopened in 2018 yet this year was when KAH really flourished by introducing a thematic international residence program, disadvantaged youth education program, a series of queer film screenings, concerts, discussions and talks.

Managerial know-how and a clear-cut vision of grassroots political and social engagement are two phenomena which for a long time seemed to be mutually exclusive in Lithuanian cultural landscape. Thus, it is exciting to see KAH dismantle this false dichotomy.

One has to mention other spaces producing wildly different yet splendid programs in 2019 such as Editorial, Lokomotif, Monto’s Tattoo. The new complex titled Sodas 2123 housing artist studios, gallery spaces and concert venues was opened at the end of the year and it is something to have an eye on in 2020.

Disappointment

Institutional Fatigue. The case of ‘The Sweet Sweat of the Future’ exhibition at the National Gallery

The slow decline in significance (one could say, latent tiredness) of two major institutions of the Lithuanian art landscape – the National Gallery and Contemporary Art Centre has been exposed this year by the proliferation of smaller independent spaces, mostly run by the artists themselves along with a few considerable private initiatives coming to the fore. Namely, MO Museum maintaining a firm foothold in terms of popularity after its opening in 2018 and several private foundations increasing their visibility and importance through proactive participation in this field.

Read symptomatically, it can be argued that both the current necessity of artist-run spaces and the success and public appreciation of private museums is due to the Contemporary Art Centre and the National Gallery being unable to formulate their respective counter-arguments and visions clearly or mediate them to potential audiences. It is a pity as strong public institutions are essential as ever: for the artists themselves, as safe havens of experimentation and criticality as well as being fundamental for writing more nuanced local art histories that evade monolithic or market adjacent vantage points often produced by the privates.

More specifically, The Sweet Sweat of the Future was an opportunity for the National Gallery to write exactly those kind of histories of Lithuanian art of the last 40 years. However, among other issues with the show, it skipped a whole generation of leading artists who created innovative post-conceptualist work between the 00s and early 10s, among them Darius Mikšys, Gintaras Didžiapetris and many others. In addition, its treatment the youngest generation of artists was equally strange, their works scattered around the space largely without a guiding motive or argument.

That the last 40 years in Lithuanian art necessitated a curatorial text of barely 3 short paragraphs did not help clear up the misunderstanding. These mostly consisted of umbrella catch-alls on our precarious futures; artistic visions of possible futures; urgency in times of political confusion in the West that we all have read in curatorial statements so many times over the last few years.

In 2019, independent spaces were able to seize what is most exciting about Lithuanian art at the moment – that is – vibrancy and intense co-existence of extremely different perspectives on what it should be. In the meantime, when private initiatives captured the imagination of wider audiences, the Lithuanian scene needs big public institutions to rethink and reconfigure themselves – and fast. They should once again take up the responsibility to be a bastion of stability and integrity, since small spaces are always fragile and private competition seems to be keen to tell us a simplistic, instrumentalised story of what Lithuanian art can be and do.

Santa Hirsch (Latvia)

This year, for the very first time, the Latvian national pavilion in the Venice Biennale exhibited a project that was a solo exposition by a female artist Daiga Grantiņa (first time when a female artist participates alone, not in a duo with a male artist or group shows as previously) and the main Art Prize in Latvia, The Purvītis Prize 2019, went to female artist Ieva Epnere.

In recent years, the Purvītis Award has been mainly dominated by male artists, except for the first year in 2009, when it was received by Katrīna Neiburga, but afterwards there almost no female artists were selected even between eight final nominees’ list. Although I’m very aware of the problems related to gender inequality troubling other Eastern European countries and their art hierarchies as well, I want to highlight these two representative achievements that are especially significant in Latvian art scene, mainly because these questions have been widely disregarded and sometimes hysterically avoided as trivial, even in art circles that define themselves as progressive.

In this context I must note puritanical mass hysteria in social networks and mass media that was caused by two students of the Latvian Academy of Arts (Ance Vilnīte & Elīna Semane) kissing performance at the ‘Academy of Arts’ exhibition in Latvia. Such reactions serve as a reminder that art should stand outside and/or against generally accepted values and norms, censorship and philistinism that currently dominate in right-wing countries.

State salaries for artists have been announced, starting from next year and giving seven artists (not researchers and curators though) a chance to receive prizes in amount of 800 EUR (average monthly wage in Latvia) per month for 12 months. This may seem like one small step in the global social security system for employees (or insecurity) It might seem one small step in global terms of art field’s workers’ social security (or insecurity) system, of the artistic sector, but this is a big step and great news for Latvian art professionals, because governmental support for visual art has been poor and private patronage explicitly conservative and almost nonexistent.

In this respect, art making was slowly becoming an expensive hobby even for the most recognized and successful Latvian artists. I hope that these new grants will finally bring back some fresh, intellectually and aesthetically daring, independent ideas in stagnating Latvian art scene.

‘Arsenāls’, the largest permanent exhibition hall in Riga, will be closing for a renovation next year. Other large scale halls are too eclectic and qualities of their programmes are often unpredictable, meaning that Latvian art scene is left with no proper, permanent exhibition space that could host wide contemporary art group shows. A lack of exhibition space opportunities correlates with a lack of curators that can work with discursive artistic practices and themes that are broader and more complicated than a retrospective. Irregularity can’t be fully supplied with contemporary art festivals that take place once or twice a year and mostly are forced to operate with too humble budget to gain international success. The same correaltion can be observed in solo exhibitions as well, Latvian artists are forced and after all accustomed to work and think in small-scale projects that lack funding and space. As a successful exception from 2019 Katrīna Neiburga’s anthropological project “Hair” at Kim? Contemporary Art Centre can be named.

Finally cultivation of regular performance art scene is developing in Latvia. This year Performance Art Festival “No New Idols” was presented by Sculpture Quadrennial Riga and Riga Performance Festival “Starptelpa” took place as well. Furthermore, performative, process-based installation “Off Spring” by artist Linda Boļšakova took place in December in gallery Alma, presenting a rare example of intellectually and emotionally subtle eco feminist art practice in Latvian art scene – what might have become a cliche in global art context, often comes as an exception in Latvia. This time a stunning exception.

The Curatorial Studies programme has been taking place in the Art Academy of Latvia for the first year – hopefully this study program will finally bring changes to the role of curator in Latvian art hierarchy, where curator is mostly seen as a manager or someone who just writes a text for the exhibition, not an important creative force that helps to contextualize ideas, practices etc.

6Although Latvian art processes in 2019 has been moderate and boring, some interesting voices can be spotted among the youngest generation of artists. Naming just a few: parody biennial MABOCA (Madona Bunch of Cool Art) was organized by artist collective GolfClayderman in a small town Madona, Jānis Šneiders’ exhibition “Place” (gallery Look), Amanda Ziemele’s exhibition “Quantum Hair implants” (Kim?), Linda Boļšakova’s “Off Spring” (gallery Alma), artists Annemarija Gulbe and Santa France, both of whom have received Grand Prix at JCE biennial, works and artistic interventions by Vika Eksta, Elīna Vītola, Ieva Kraule-Kūna. These and some other artists who started their careers recently give hope that “something good is going to happen”, despite overall stagnation.

Miroslava Urbanova (Slovakia)

This year on the Slovak art scene was anything but boring. At least two positively memorable anniversaries had been celebrated: the 30th anniversary of the velvet revolution that pushed the institutions to reflect on the topic of freedom and the relationship between art and politics and the 70th anniversary of the Academy of Fine Arts and Design (AFAD) in Bratislava with the inauguration of the new headmistress Bohunka Koklesová. The cultural scene is growing, becoming more inclusive, decentralizing itself across the regions, where interesting events and exhibitions take place – from contemporary art spaces such as EQO in Spišský Hrhov, through Diera do sveta in Liptovský Mikuláš to multi-genre festival Medzihmla in Lučenec. It was a year of remarkable collaborations within and beyond visual arts bubble.

Stojíme pri kultúre!/ We stand by culture!

What began as a student initiative of the AFAD in Bratislava to support endangered status of Kunsthalle Bratislava as an (in)dependent institution, slowly became the platform to facilitate the broader dialogue between the cultural workers from over 120 Slovak cultural institutions and the Slovak Ministry of Culture, currently led by the nominee of SMER-SD Ľubica Laššáková. Stojíme pri kultúre!/ We stand by culture! started petitions, organized protests and opened public discussion with the representatives of the Ministry of Culture. Mrs. Laššáková´s vision of culture in general favors the support of the folk culture and had significantly reduced the budgets of major cultural institutions.

Furthermore, in case of the funding of marginalized groups by the Ministry of Culture came this year to the marginalization of the LGBTQ+ (despite of that and fortunately, e.g. the zero year of the festival of transgender culture took place this year at A4 in Bratislava). Standing by culture means to take action when the idea of culture begins to solidify into a vague form of what is perceived by conservative politicians as national.

Kapitalks

The engaged newspaper Kapitál (established in 2017) went beyond the printed issues with the discoursive format of talks – Kapitalks that invites local and international guests to discuss topics as postsocialism, sexuality and intimacy, sports, education or mental health. It does so during the festivals or within the thematic exhibitions and broadens the awareness, posits new points of view and rises intellectual level of the discussions about the given topics.

Zlaté časy/ Golden Times

Was the year 2019 golden time of the Gallery of Jozef Kollár in Banská Štiavnica? For visitors keen on contemporary art for sure. The curator Mária Janušová and the artist Lucia Tkáčová prepared for the regional gallery in the formerly famous mining city such programme that changed its sleepy character of tourists´ reservation into a lively cultural hotspot with interesting lectures, screenings and exhibitions, especially during the peak of the season in the summer.

Petržalka Gallery Weekend

Four independent spaces for art and culture can be nowadays found in the biggest residential district of Bratislava – (in)famous block of flats jungle Petržalka – namely HotDock, Temporary Parapet, Photoport and LOM. They established and organized for the first time the format of the gallery weekend in Bratislava – Petržalka Gallery Weekend with the ambition to awake the interest of a broader public and local community, accompanied with gallery weekend newspaper. I found their newspaper at my favourite burek bakery months after the end of the event. Long live Petržalka art spaces!

Anna Daučíková: Work in Progress: 7 situácií/ 7 situations

This year’s must-see was (and in 2020 still is) the solo exhibition Work in Progress: 7 situácií/ 7 situations of the pioneer of intermedia, feminist and queer art in Slovakia – Anna Daučíková at the Slovak National Gallery. After the exhibitions of Jana Želibská, Denisa Lehotská and female sculptors from the 1950s onwards pays this exhibition tribute to the important female representative from the local art scene that is well-known beyond Slovak borders. The exhibition is not a retrospective of the artist, but rather an attempt to take a look at her previous and current works as open, still in progress, presented in collaboration with other artists and guests.

Ekológia túžby/ The Ecology of Desire of the finalists of Oskár Čepan Award 2019

After last year´s restart – the zero year of the Oskár Čepan Award for Young Artist – is this year definitely a strong one. The international jury chose five distinctive finalists – Ján Ďurina, Milan Mazúr, Dávid Koronczi, Erik Sikora and Gabriela Zigová. The exhibition Ekológia túžby/ The Ecology of Desire (curated by Václav Janoščík) at the Eastern Slovakian Gallery in Košice presents their latest works and artistic programs in general in both comprehensible and elaborate manner and is worth to visit.

Slovak artists represented at the art fair Vienna Contemporary

Art fairs became one of the most powerful exhibition platforms with curated sections and accompanying program. During this year’s nearest renowned art fair – Vienna Contemporary were very well represented Slovak artists. After this year’s closure of Krokus Gallery remained on the Slovak artists in my opinion only three internationally relevant private contemporary art galleries capable of representing Slovak artists abroad – two of them were present at Vienna Contemporary: SODA Gallery and Zahorian & Van Espen. SODA showed in the curated section Explorations works of neo avant-garde artists such as Milan Adamčiak and Michal Kern. Zahorian & Van Espen exhibited works by contemporary artists, among them Jaroslav Kyša and Štefan Papčo. Jiří Švestka Gallery from Prague devoted the whole booth to Katarína Poliačiková. In the Focus: NSK State in Time of the curator Tevž Logar was included Ilona Németh.

Collaborations of the architect Jakub Kopec

The exhibition project Vedúca skamenelina/ Index Fossil at the New Synagogue in Žilina (curated by Ivana Rumanová), the 70th anniversary exhibition of the AFAD Y at the Umelka Gallery in Bratislava (curators: Barbora Komarová, Ľuboš Kotlár, Miroslava Urbanová), one gallery year Zlaté časy/ Golden Times at the Gallery of Jozef Kollár in Banská Štiavnica (concept by Mária Janušová and Lucia Tkáčová) or a new playground on the spot of the former cemetery in Leopoldov (together with Klára Zahradníčková and Tomáš Džadoň, awarded with CE.ZA.AR 2019) are some of this year’s collaborations of the Czech architect Jakub Kopec (currently teaching at the AFAD in Bratislava) and aforementioned art practitioners – artists, curators, other architects. Kopec’s proposals and interventions are typical of their technical sobriety, diversity and simplicity combined with impressive effects, high utility and low maintenance. They prove that collaboration with an architect through realizing exhibitions and not only can be beneficial not only in the sense of re-building and accentuation of the space, but by highlighting its various social functions.

Retelling (his)stories by female illustrators

In contrast to the wave of conservatism concerning abortion rights and repeated rejection of Istanbul agreement by Slovak lawmakers, there were nice homages to independent womens’ contribution to Slovak society, especially in cooperation with talented illustrators. In 2019, the first female president of Slovak Republic Zuzana Čaputová was elected and her success story was immediately illustrated within the project Svetlo pod perinou/ The light under the bedsheets. Later, the illustrated book Kvapky na kameni/ Drops on the stones was published – it unfolds 50 stories of brave Czech and Slovak women. Since 2016, a powerful generation of female illustrators contributes to the feminist newsletter Kurník, which also this year gave space to interesting voices – e.g. to the researcher Zuzana Maďarová to retell the story of the velvet revolution – with the focus on the role of women in it. They use the power not only of words, but also that of pictures in its best sense.

Gergely Nagy (Hungary)

About pluses and minuses in 2019 in Hungary

I am not too good at listing things and compiling “best of” rankings. What’s more: the situation in my country really does not make it easy for anybody to put together lists of this kind. Publicly funded art institutions almost entirely lost their autonomy and professional decision making processes, so when we are reviewing their exhibitions we do not always know what we are actually reviewing. The compromises they made? We are not able to talk about exhibitions and institutions because we always find ourselves talking about the circumstances instead: political positions, lack of opportunities, lack of funding, boycotts and anti boycotts.

In the country’s ever-changing (rather ever worsening) political situation it is a huge effort not to miss the blurring boundaries between the regime’s territory and “our” territory, between independency and collaboration, between staying out and giving in.

So when we say “this was the best exhibition in Hungary in 2019” then we probably say: this was the only institution which could defend its autonomy successfully enough to make something good. Or: this was that artist who has been compelled to make the minimum amount of compromises to carry through his or her concept.

Let’s not forget: we are talking about a country from where the government pushed out the highest ranked university forcing it to operate somewhere else. Where the government simply cut off the research institutions from the body of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences only to control them. Where the state budget gave 9 billion HUF to the MMA (Hungarian Academy of Art) for its loyalty and being uncritical, and only 20 million to the SzIMA (Széchenyi Academy of Letters and Arts) as a punishment for its critical views and membership. Where the government media is regularly leading hate campaigns against independent artists. Where the government simply swiped gender studies out from the universities. Where the ruling party attempted to end the 26 years long history of NKA (National Cultural Fund of Hungary), that used to be the biggest autonomous project-funding initiative in the field of arts and culture.

Let me not to continue this.

There was an art project this year that reminded us to the times when the institutions could deliberately choose artists to work with. When artists could consider larger formats because they could get support from institutions. This was The Blue Room by the artist group Tehnica Schweiz. The group (Gergely László lives in Berlin, Péter Rákosi lives in Budapest) started a project in 2017, which resulted in two exhibitions in 2019 presenting an installation and a film.

The “Blue Room” itself is the main hall of a synagogue in Tata, a small town 70 km’s from Budapest. After the Holocaust – the death of 400 thousand Hungarian Jews –, in the towns where almost every Jewish inhabitant were deported from and killed, the disused synagogues were closed and abandoned or sometimes turned into storage spaces. Or – like in this case – inherited by the local museum. This room of the Tata synagogue in 1977 became an exhibition space of the Museum of Fine Arts’ late 19th century plaster copies of antique sculptures. In 2018 the collection was moved away from this 18th century building to be exhibited somewhere else.

“The blue room” installation and video, 18 min, photo Peter Rakosi, tehnica schweiz

Tehnica Schweiz filmed the whole process of dismantling and moving and then moved in the copies of the copies: the students of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design produced small porcelain copies of the plaster sculptures. Tata’s Jewish community had a legendary figure, Mór Fischer who once was the founder of the famous Herend porcelain factory. The associations are countless. Showing the excellent pieces of the ancient Greek and Roman art in the spiritual home of a community which was killed. Showing human bodies in a space where this was not allowed according to the rules of the religion. Moving in and out. Trying to reproduce the reproduction using a noble material instead of an ephemeral one. Questioning and rethink the space and the cultural heritage on multiple levels.

The exhibition consisted of the video footage – with wonderful soundtrack with Greek and Jewish themes – and the installation. It was shown in Tata synagogue as well as in a damaged former Christian church turned into exhibition hall in Budapest’s Kiscelli Museum. Needless to say, placing the synagogue into the church was also a significant gesture here.

The Blue Room was not only an outstanding project. But also turned the attention towards the context. Normally, these kinds of projects, taking years to accomplish, using different media, difficult technologies and backed by several institutions would not be exceptional. But here and now we are not used to artworks that are imagined and planned in a larger scale, having the time for a proper research and professional work, reflecting our past and present times from a certain perspective that only contemporary visual art can have.

When critical art is marginalized, there is chance that soon the art production itself will be marginal and insignificant as well.

Indrek Grigor (Latvia)

Please do not get me wrong, there were quite a few interesting and noteworthy events and exhibitions in 2019. But. And it’s not like I have really dwelled into annual roundups, to look for inspiration. But from the few Estonian 2019 art tops that I had a glance on, I discovered rather as a surprise for myself, that for example the Venice biennial was mentioned only in the context of the Estonian pavilion and the Lithuanians. The latter I suspect first of all because they won the golden lion. In conclusion, it seems then, that there were more impressive events than usually, but they were evenly distributed. So instead of telling you for example about the great program of the Tallinn Photo Month, I will point out two exhibitions by classics, which took place in Tartu.

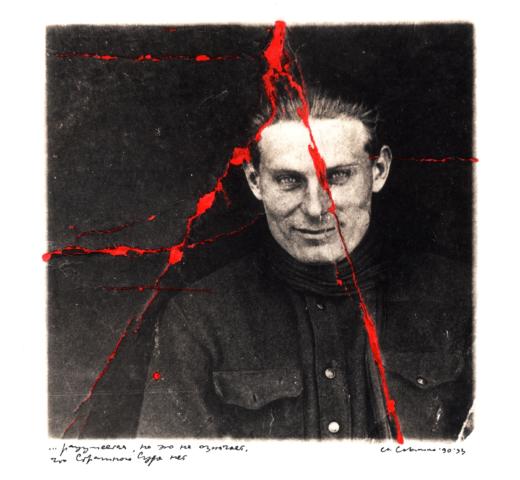

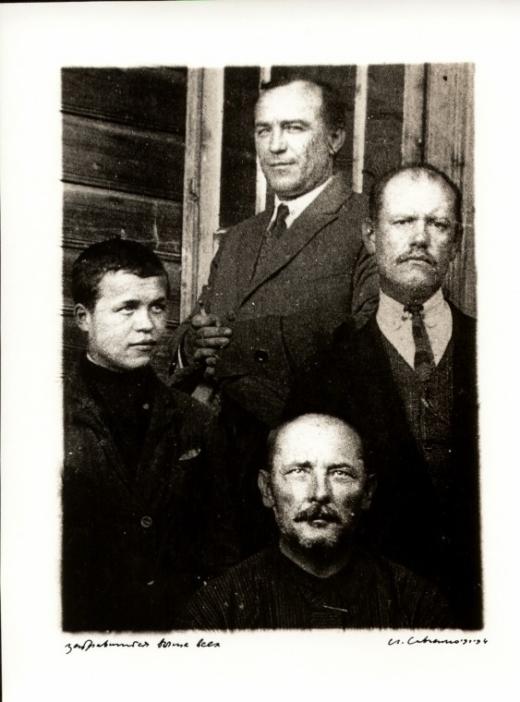

Igor Savchenko. “See kes jõudis ära oodata oma prao. Muidugi. …mist pole olemas”

Igor Savchenko “See, kes on tõusnud teistest kõrgemale”

Professor Peeter Linnap, who these days is first of engaged into publishing books on the History of Estonian photography, decided to pep up the exhibition program of the Pallas University of Applied Sciences gallery in Tartu and contacted some old friends in this matter. As a result of this the gallery hosted in spring a remarkable exhibition of works by the Belarussian photographer Igor Savtšenko. Which was followed in autumn by no other than Martin Parr. The latter exhibition was accompanied by a small deliberately low-fee publication, which I guess Parr was right when he said, raised in prize the moment you bought it. It’s a shame I didn’t.

Parr displayed a series of photos he had shot in the early nineties whilst working in Finland and making trips to the newly independent post-soviet republics. It was the time when Parr’s The Cost of Living was making its rounds around the world, stopping in 1992 also in Tallinn. Those the material Parr shot back then in our region had a similar approach as the Cost of Living that had just made him into an international superstar. But there were of course local particularities, to how consumption looked like in the Baltics in the early nineties as compared to the middle class in Great Britain, it must have felt like a curved mirror to Parr. But the same goes for how both of Parr’s exhibitions have been perceived in Estonia. In 1992, in the midst of deficit, nobody could really relate to the criticism of consumption Parr’s The Cost of Living was transmitting. And now 25 years later, instead of looking at Parr’s photos from back then as a documentation of changing times, the locals delved into nostalgia.

Martin Parr “A4”

Martin Parr “Banaanijärekord Tallinnas” 1992

Igor Savtšenko, whose collection of the most famous series in his portfolio proceeded Parr’s exhibition, got, as one can expect, lesser attention. But what unites the two authors is their relationship with Estonia. Having participated in one of the most important exhibitions in the history of Estonian art life The Saaremaa Biennial in 1995 which was co-curated by the same Peeter Linnap by whom Savtšenko was now again invited to Estonia. Whereas the works or at least the topics overlap. But the weird thing is, that when with Parr one could feel that he has initiated and lived through a revolution. His has brought a change in to the perception of what documentalism is. To the extent where many others and me do not even anymore understand the need for his justifications of depicting the life of ordinary people. He has lived through a brake I the state of mind, which makes him at times sound lie a veteran. Savtšenko’s on the other hand with his cut out family albums, altered memories and play with the basic characteristics of the photographic medium – time and light – is as topical today as he was in the early nineties.

Sorry, I cannot think of a real moral in this story. Let’s just call it an observation of the year.

Oleksiy Radynski (Ukraine)

Venue of the year: the Kmytiv Museum of Soviet Art

In an art museum housed in a Brutalist building that towers over a decrepit village of Kmytiv, 100 kilometers West of Kyiv, a series of exhibitions were organized by Yevgeniya Molyar and Leo Trotsenko of the DENEDE collective, and curated by Nikita Kadan.

With Oleksiy Radynski

This museum, built in the middle of nowhere in the 1980ies by a local party official, boasts a significant collection of Socialist Realism. These Soviet-era treasures, which gained new significance in an era of Ukrainian ‘de-communization’, were revisited by the curatorial team by combining the archival works with contemporary pieces. If anyone ever thought that ‘de-communization’ was somehow a liberal idea and not an instrument for fascist hegemony, they were proved ultimately wrong by the far-right backlash against this project, which took truly phantasmagoric forms.

Still, the attacks on this exhibition series must not eclipse their unique content, which included, among many others, the wrks by Anatoliy Belov, Alla Gorska, Ilya Kabakov, Lada Nakonechna, Vlada Ralko, Sean Snyder, Volodymyr Vorotniov, Florian Yuriev etc.

Event of the year: Oleg Sentsov and Sasha Kolchenko released from Russian jail

Crimea-based arthouse filmmaker Oleg Sentsov and antifascist eco-activist Sasha Kolchenko were illegally held in Russian prison camps after they were kidnapped by the Russian secret service during the military invasion of Crimea on 2014. For more than 5 years, artistic and activist communities were struggling for their release. In September this year, this campaign became an unexpected success when Sentsov and Kolchenko were released in a prisoner swap between Russia and Ukraine. Sentsov’s new film, based on his directorial notes sent from jail, is going to premiere at the Berlinale in February 2020.

Artist of the year: Florian Yuriev

Just a couple of years ago, very few people knew of the existence of this conceptual artist, theorist, violin maker, and architect. When Florian Yuriev’s architectural sum total – Kyiv’s famous UFO building – came under attack by the developers who wanted to turn it into a shopping mall, Yuriev was finally rediscovered. Now, he is experiencing something of belated fame. This year, Florian Yuriev had celebrated his 90th birthday and had his first solo retrospective at the National Art Museum of Ukraine, while battling both a severe form of cancer and the stupidity of state officials who still cannot resolve the fate of his architectural masterpiece. He is also a subject of two documentary films currently in production (full disclosure: I’m directing one of those).

Failure of the year: Manifesta (not) in Kyiv

This year, Kyiv has become the European capital of cultural destruction, with three iconic cinemas shut down and handed over to wealthy developers, and a number of other cultural spaces (including commercial galleries) wiped out of the city center by skyrocketing rent prices. The city government decided to shroud its all-out attack on cultural institutions in the mirage of global art industry: by inviting Manifesta to organize one of its next editions in Ukraine’s capital. Miraculously, Kyiv (a city that currently can boast not more than three venues suitable for presenting) was included in a short list, where it ultimately to Kosovo’s Pristina. And rightly so.

Anna Remešová (Czech Republic)

I think 2019 was a good year for the art scene in Czech Republic. There was a lot of collaboration across fields and disciplines, few cultural institutions in two biggest cities – Prague and Brno – initiated coalitions that were demanding the climate emergency declaration and dozens of other art and cultural institutions and organizations joined their appeals. Even if the city councils haven’t declared anything yet people in those institutions had to start to think about their daily practise, how they behave, what they do with the waste and overproduction of the program etc. The possibilities of the necessary ecological transformation of the institutions have become a huge topic. And it’s not only the museums and galleries but also art academies where student initiatives and collectives (such as Eco-cell AVU or UMPRUM in the climate emergency) have emerged.

The businessmen Petr Pudil and his bodyguard (in the middle) talking during the event Washing Kunsthalle organized by initiative Studio without Master against the activities of Kunsthalle Praha founded by The Pudil Family Foundation. June 16th 2019 in Prague, photo. Denisa Langrová

“Logistics Landscape” show curated by Kateřina Frejlachová, Miroslav Pazdera, Tadeáš Říha, Martin Špičák in VI PER Gallery Prague, 13/2–6/4/2019 photo. Peter Fabo

Installation view of the Carnations and Velvet show in Prague City Gallery, curated by Sandra Baborovská, Adelaide Ginga, 30. 4 – 29 9 2019, photo: Tomáš Souček

UMPRUM Academy of Arts Design and Architecture in Prague, Photo. UMPRUM v klimatické nouzi (UMPRUM in the state of climate emergency) Facebook

Few oligarchs opening their art centers and galleries had to face the protests of art students. Namely the former coal baron Petr Pudil with the first art event of his Kunsthalle Praha (it should be fully opened in 2021 in the centre of Prague) or Robert Runták, the head manager of the bailiff company, during the opening of his art centre Telegraph in November.

I observe with enthusiasm the book edition called .txt which Display, APART collective and Kapitál newspaper jointly produce because they focus on super important topics. There were three small anthologies so far: Iné telá (The Other Bodies), Neviditeľná staroba (The Invisible Old Age) and Klimatická kríza (The Climate Crisis). Regarding the curatorial work I enjoyed a lot all the shows in VI PER Gallery this year. I have just realized that it is probably the only one gallery where I regularly see each exhibition. This is definitely not the case of the National Gallery and its program which is in a deep deep crisis because of the dismissal of the director Jiří Fajt, curator Adam Budak and the chaos it evoked. The only chance is that this crisis will lead to a change or reform.

Probably bit unexpectedly (but I am a very bad exhibition visitor) as a well-done show I would like to mention the Carnations and Velvet about the revolutions in Czechoslovakia (1989) and Portugal (1974) in the Prague City Gallery because it learned me a lot about the fluidity of the revolutionary symbols and political beliefs. From all the anniversary events of the year 2019 I enjoyed it the most. And the best art piece of the year? Most likely Magdalena Kwiatkowska’s project at INI Gallery which offers a temporary substitution of a community place for homeless women from the Jako doma NGO who had to move out from their space at Florenc. Sometimes there is place for art, sometimes not, I guess that’s nice about the galleries.

Anna Łazar (Poland)

Feminale in Bishkek

Feminist Biennale of Contemporary Art at the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts in Bishkek, “Nourishers Economic Freedom” is the slogan of the first Feminale organized by curators Altyn Kapalova and Zhanna Araeva that has been dedicated to 17 migrant women, mostly from Kyrgyzstan, who died in a fire at a printing house, where they worked in Moscow in 2016. Women’s art is revolutionary and dangerous, so Feminale was censored and the director of the museum forced to resign. The Kyrgyzstan`s Ministry of Culture -seems to have habits similar to our Polish MoC. In a gesture of solidarity, artists from various countries published works on feminist thread #SupportFeminnaleBishkek #феминале #savekyrgyzfeminnale #nakedinart #соскиугрожаютгосударству #этовыугрожаетемиру. -On the other hand the ‘International Forum for Contemporary Art’ initiated by Sabina Shikhlinskaya over a decade ago in Baku took place again this last September, called “MAIDEN TOWER. To be a Woman” without anyproblems. On this occasion even a mural – with, Oh no! visible non-heteronormative sex characteristics, was created! It is not easy overall, but to paraphrase the slogan of the Komuna Warszawa it is time to admit: Feminism is.

Not only “Revolt of the Deaf”

They were talked about, represented, involved in projects, their world was observed, adapted to imagination of complementarity until finally they were -noticed and spoke -with their own voice. Daniel Kotowski’s performance “I have a duty” on the 97th anniversary of the murder of President Narutowicz, ” Rebellion of the Deaf” by Bogna Burska, “The Show” of Theater 21 in Zachęta Gallery and “One gesture” by Wojtek Ziemilski in Nowy Teatr brought original, strong poetics, important social recognitions and the story of the politics of deaf people defined by themselves.

Polish and Ukrainian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Roman Stańczak’s „Flight” and Open Group “Shadow of the Dream” seem complementary.The plane is a sculptural object, permeated, accessible to the gaze and enclosed in the exhibition space, controlled by the gesture of one artist versus the shadow of the plane, the lack of an object, shedding light on the gray zone of informal influences in art. Inclusion instead of selection, i.e. an invitation to the Ukrainian pavilion at Venice Biennale of all willing artists who apply alone versus properly organized competition and compromise. Tu-154 crash in Smolensk and Malaysia Airlines 17 near Hrabowy. The inverted object lies very close to utopia – not the place. Eliteity( ? Elitism) versus egalitarianism. One highlights the other.

The legacy of the Soviet Culture

The focus on USSR legacy I-in the arts has long been limited to avant-garde movements, connected with the international currents of the beginning of the 20th century, headed by Bauhaus. For a few good years now, gaze at arts during communism has been more reflective, which is visible – in the activities of the DE NE DE group, that studies the cultural heritage of the early 20th century : monumental art as well as museums in the Ukrainian villages and towns. This year, the curatorial project of Mykyta Kadan with Jeheniya Molyar at the Museum of Fine Arts in Kmytiv (created in the 80s on the initiative of a retired military man, who took delight- in art while working as a civil defence instructor at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg), was really electrifying. The curatorial project referred to universal education, modernization, society, war, national liberation movements, human body and privacy as well as the artist’s figure, art as such and became a base of the new permanent exhibition of the Museum in Kmytiv. Everything is in the negotiation field between artists, museum staff, local and central authorities. Anyway, apart from the series of exhibitions we are dealing with the civic acceptance of the need to take care of the cultural legacy of the Soviet period-in the context of the country that a) is poor, b) is currently -overwhelmed with the war with Russia, c) =is occupied, as always ,with – brokering deals with the oligarchs, d) last but not least, steadfastly denies all Soviet legacy as foreign, oppressive and -nonexistent. In addition, it is a practical decentralization of cultural capital and the activation of provincial communities.

Babi Badalov on “Today we are going to invent the nations” exhibition in Kmytiv Museum, fot. N. Dyachenko

Bik van der Pol in Ujazdowski Castle

I – found the exhibition “Far Too Many Stories to Fit into so Small a Box” -at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw not only as a story about the -suspious status of works from the collection, their various oddities or neglections, but also about the fact that the change of the political system promotes freedom, experimentation, and ecstasy, thanks to which contemporary art has made such a thrilling experience. The more global art structures that are closely tied t to the art market are installed in Poland, the more petrified the art space, as t calculations of long-term profits and losses are made. Understanding is greater, risk is less likely. I recently read the book “As many years as Polish People’s Republic or 45 years since Tuesday” by former director of Ujazdowski Castle published in 2015 and I think that I would love to see an exhibition, a film or read a book that would show the CCA in a broader social and political context -of those processes Poland. We already have a myth outlined, as well as its deconstruction, so what is truly needed now is a large research team and a long-term project around the history of the Castle .The Castle has earned it.

Kiki Smith “I am a wanderer” in Oxford

The artist’s magnificent retrospective -at Modern Art Oxford, built with a sense of humour and universal breath, is also a critical observation of universalism and a testament to the beautiful history of her artistic choices. Kiki Smith’s intellectual challenges are – inviting a dialogue, despite their enormous craftsmanship they are not hermetic, and encourage a viewer’s partnership with the artist’s -gaze at cultural history. Smith says: ‘We are interdependent with the natural world… our identity is completely attached to our relationship with our habitat and animals. I make things from images that catch my attention.”

Five-year Biennale in Oslo

The first edition of the Oslo Biennale was – labeled the anti-Venetian. Scheduled -every (?) five years, it focuses on social and political issues and is certainly anti-spectacular. Events are unspectacular, scattered and not the objects but the processes are at the center, including situations that have not occurred. For example, Jonas Dahlebrg’s project is about how his idea of commemorating the victims of Utøya Island was -never realized. The artist had thought about cutting through the island. Interestingly, one of the most important counterarguments to his idea concerned ecology. Katja Høst proposed a series of postcards taking a position in the defense against the destruction of the brutalist Y-Blokka building with decorations by Pablo Picasso and Carl Nesjar, which is not only a great example of modernism, but also a monument to the government of the Norwegian Social Democrats.

Katja Høst / osloBIENNALEN © 2019

Vanessa Gravenor (Germany)

Disappointments—Déjà vu