Top 10: Art in Central Europe 2017

Top 10 Ukraine

Oleksyi Radynski – Filmmaker, Essayist

Ukrainian Filmmaker and Anti-Fascist Activists Remain in Russian Prison

Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov and anti-fascist activist Sasha Kolchenko are still in a Russian prison. They were sentenced to 20 and 10 years respectively on made-up charges of planning terror attacks in Crimea during the Russian military occupation of the peninsula in the spring of 2014. Sentsov and Kolchenko were jailed by an Orwellian show trial which was meant to suppress any resistance to the Russian annexation of Crimea and foster the fake notion that, the “total majority of the Crimean population supports Russia.” For the development of Ukrainian art, it is extremely important that an artist was picked as one of the scapegoats by the Russian security services (which, in 2017, finally started to jail Russian filmmakers, as well).

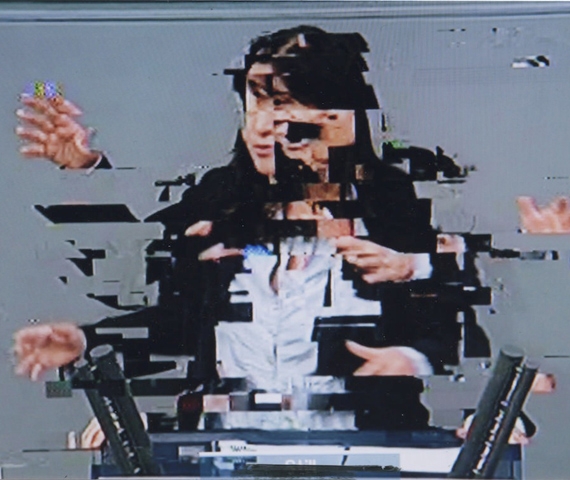

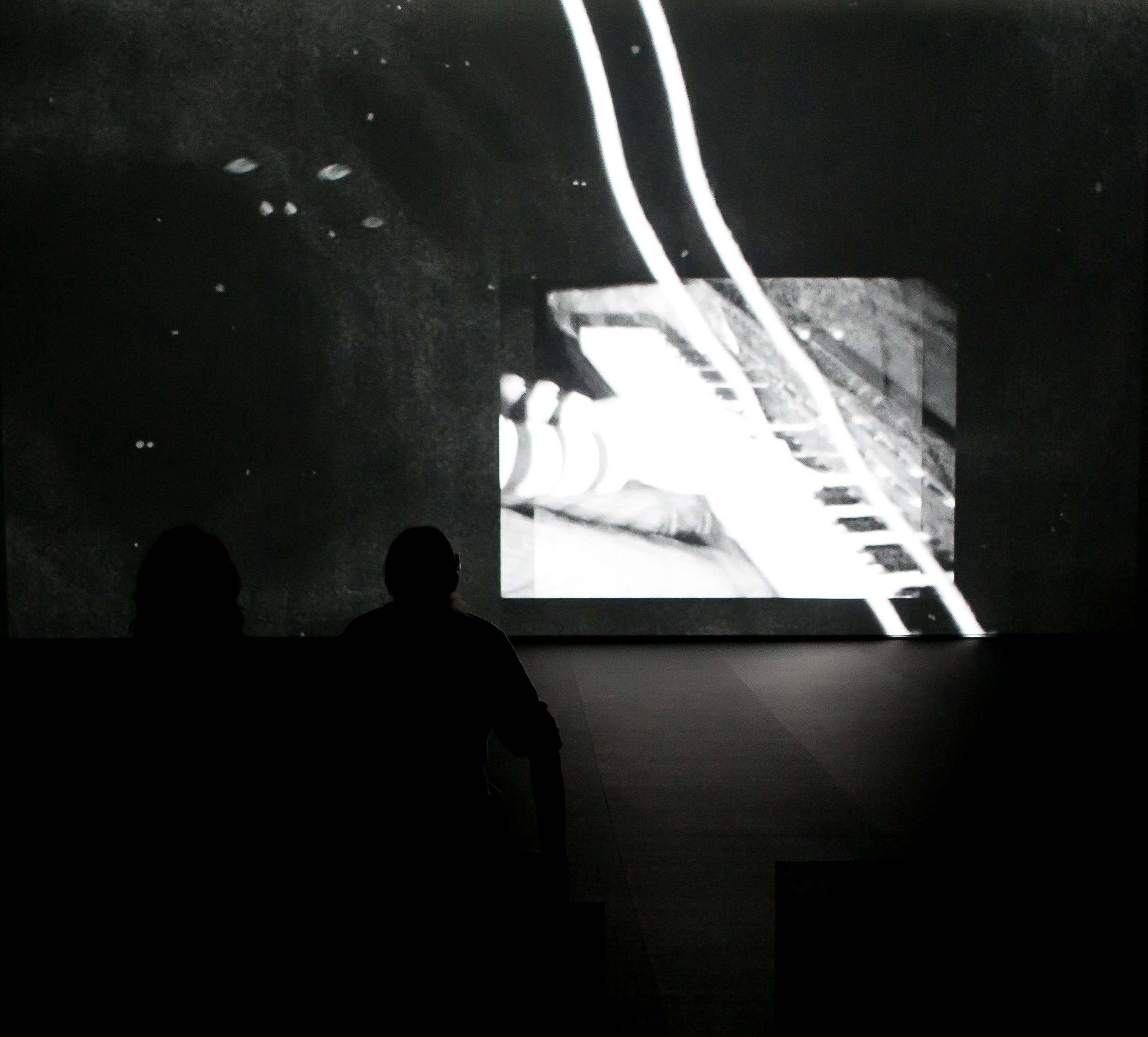

Boris Mikhailov’s Parliament Series at the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

The conceptual photographer who created one of the most influential bodies of work from 1970-80s in the Soviet Union has long been ‘out of joint’ with contemporaneity–especially since his emigration from Ukraine to Germany in the 2000s. In the Parliament series, he has finally delivered a precise and devastating commentary on the globalized media environment we all live in. In this new work, Mikhailov photographs the debates in the German parliament as seen on a TV screen, distorted by satellite noise and other technical glitches. The result is an uncanny mixture of abstract and figurative images, what Mikhailov himself calls, “the assault of suprematism on reality,” depicting the ongoing collapse of political representation. In fact, it is not about Boris Mikhailov finally catching up with the current political reality, but vice versa, it is about Western society more and more resembling the so-called ‘years of stagnation’ in the socialist bloc, an era so brilliantly represented by Mikhailov in his own era.

Vova Vorotniov Walking 1,000 KM from the Polish-Ukrainian Border to the Donbass Region of Eastern of Ukraine

Vorotniov was carrying a piece of coal dug up in his hometown of Chervonograd, part of the Lviv-Volyn Coal Basin, to a local museum in Lysychansk, a coal-mining city not far from the current frontline. This five-week-long action, followed live by Vorotniov’s audience on social media, was at the same time an exercise in experimental ethnography, a commentary on the Ukrainian internal colonialism and the East/West divide, and an apogee of Vorotniov’s own practice of walking as artistic work.

Soshenko33 Collective (Anna Sorokovaya and Taras Kovach) Became the First Artists from Ukraine Ever to be Invited to Participate in documenta

As a response to this invitation, they, in turn, invited a group of fellow artists to create a collaborative artwork in Kassel, together with a local grassroots collective called Tokonoma. This process-based collaboration resulted in an ironic commentary on the all-pervasive idea of ‘participatory’ or ‘collaborative’ work itself. The artists have jointly constructed a fully operative shower cabin in an art space, which significantly improved their own living conditions during their stay in Kassel.

The Cynocephali of Donbass by Liya Dostlieva

For this ongoing series, the artist, who is originally from Donetsk, accepted requests from those who were born in the Donbas region of Ukraine to produce their portrait in a form of a doll with the head of a dog. This refers both to the ancient Greek myth claiming that the territory now known as Donbas was populated by Cynocephali, or people with dog’s heads; and to the current Ukrainian othering of Donbas and its dwellers, many of whom had to move to other regions of Ukraine as internally displaced persons, fleeing war.

Gradual Re-discovery of the Oeuvre of Florian Yuriev

Florian Yuriev is an abstractionist painter who developed his own synaesthetic theories back in 1950s, the last project he undertook before turning his attention to architecture, creating the famous ‘Kyiv Flying Saucer’ building, which was supposed to house the synaesthetic theater for the ‘music of color,’ but ended up housing the KGB-backed Institute of Information. In recent decades, Yuriev has abandoned architecture and turned instead to violin-making. In 2017, his ‘Flying Saucer’ building came back into the spotlight due to attempts to turn this modernist landmark into a shopping mall. The building became the main venue for the 2017 Kyiv Biennial, and also sparked a civic resistance movement under the hashtag #savekyivmodernism.

Stick Apart by Maria Plotnikova

Participants of this collective performance connect their bodies with wooden sticks and try to move around as a group for as long as possible, inevitably losing all their connections in the process. The result is an impressive image of network and alienation, potency and helplessness. This piece, performed at Maidan square in Kyiv, was seen by the jury as deserving of the main prize at the Biennial of Young Art in Kyiv this year.

Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics, a Photobook by Yevgen Nikiforov

For this project, the photographer has documented hundreds of Soviet-era mosaics all over Ukraine. Some of them are among the most outstanding forgotten artworks of the Ukrainian twentieth century, and many of them are now under threat of destruction due to barbaric laws on ‘decommunization.’

Frost, a New Film by Sharunas Bartas, Shot in War-Torn East Ukraine

Although this work formally belongs to film industry rather than contemporary art (it stars Andrzej Chyra and Vanessa Paradis, among others, and was premiered in Cannes), the unique filmmaking style of Bartas undoubtedly places Frost among the most important artworks produced in Ukraine this year. As always, Bartas in this film merges documentary observation and immersion into the filmed environment with arranged situations and subtle intrusions by professional actors. In Frost, he observes a Lithuanian couple that goes on an obscure journey to the war zone, creating a film about war spectatorship and the unavoidable failure to represent war.

Svitlograd by Alina Yakubenko

This mockumentary is based on a Soviet-era unrealized project to merge the three industrial cities in the Donbass region into a futuristic agglomeration Svitlograd (The City of Light). In her video, Alina Yakubenko reinvents this project by imagining the artistic gentrification of the three depressed post-industrial cities that were supposed to comprise Svitlograd. This is a timely critique of artistic industry and ‘creative economy’ now surging in Ukraine, which are trying to heal the deeply entrenched social disasters by providing illusionary privileges for the selected participants of the so-called ‘creative class.’

Top 10 Latvia

Santa Mičule – art critic, editor of Echo Gone Wrong

A Look Back at 2017 in Latvian Art News

This year the most striking events in the Latvian art world were associated with various cultural, political and institutional decisions and actions. In contrary I’d like to begin with the Purv, which was awarded to a group of artists — Krišs Salmanis, Anna Salmane and Kristaps Pētersons — for their work Song (curator Šelda Puķīte). The Purvītis Prize is the most prestigious art award in Latvia, the winner receives around €30,000, an impressive amount of money considering the modest budget assigned to Latvian culture in general. In 2017, the prize was awarded for the 5th time and rather delightfully to a winning art project that many considered to be a very brave selection. In previous years, the prize had received a lot of criticism for focusing on overtly traditional and museum-like art practices. Song is an ironic sound installation supplemented with musical performances exploring the traditions of the Latvian Song Festival, which to this day remains dominated by 19th century values of national patriotism.

LOW Gallery and 427 Gallery Continue to Make Waves

LOW Gallery was launched in the spring by artist Maija Kurševa and has become an important art place for non-commercial projects. Together with Kaspars Groševs’s 427 Gallery, they round out some of the rare artist-run art spaces in Riga, offering a creatively autonomous view on Latvian and European contemporary art. Both galleries are open to experimental new trends instead of simply exhibiting the same tired formats over and over again. Despite the activities of these two galleries, there still remains a distinct lack of professional alternative art spaces in Riga. [Sadly, in late December, only a week before the end of 2017, 427 gallery got news from the State Culture Capital Foundation in Latvia that it will no longer support the gallery in 2018. In response, the gallery has launched an Indie GoGo campaign to raise funds to support it’s yearly operating budget into 2018, featuring an auction of works donated by the likes of Jaakko Pallasvuo and Bora Akinciturk. – eds.]

Skepticism Continues to Haunt the 1st Riga Biennial Set to Take Place in 2018

At the start of the year, the Riga Biennial Foundation announced that the first Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art will be taking place in 2018. The renowned curator Katerina Gregos has been appointed as its first curator and organizers have vowed to promote artists from the Baltic States internationally through this event. However, the response from local professionals has so far been skeptical, with some speculating that the motivation behind the decision to invest private fundings into a biennial relatively new and unconnected to the Latvian art world. In addition, further doubts have been raised about the organizers’ knowledge of Baltic art, thus eliciting associations with a colonial approach whereby a large art event is thrust into a public space without any regard for the local specifics.

Feminism Makes a Splash in Latvia

Several art projects inspired by feminism emerged this year, much to the delight of myself and other local cultural practitioners. The exploration of gender issues is still considered a taboo subject in Latvian art, often met with incomprehension even by art professionals. Although it might be an exaggeration to call what happened this year a new wave of feminist art in Latvia, numerous projects in 2017 reflected on what Judith Butler famously called “gender trouble.” Thus raising hopes that one day this theme could become a legitimate (i.e., demanded) subject in Latvian art. Among these projects was one by Ingrīda Pičukāne, an exhibition called The Red Room dedicated to the menstrual cycle; the exhibition featured an accompanying zine called Samanta, which focused on the issue of body-positivity. In addition, two exhibitions curated by Jana Kukaine, entitled I Touch Myself and Goddess Ex-Machina, as well as a programme of exhibitions and performances at Tartu Art House curated by Šelda Puķīte, featured artists Margrieta Grietiņa and Mētra Saberova.

Changes to the State Culture Capital Foundation Allocate Money from Vices to Support Culture

The Ministry of Culture announced significant changes in relation to the State Culture Capital Foundation and the way it operates this year. The changes are a return to a previously applied financial model that ensures 3% of excise duty from alcohol and tobacco, as well as 10% from lottery and gambling, will be allocated to financing culture. In the long term, hopefully, this model will lead to increased budgets for cultural projects, which in turn will enable the Foundation to remain autonomous from the decisions of politicians and the effects of an unpredictable Latvian tax system. The State Culture Capital Foundation currently has a €9 million budget and despite the steady annual increase, this amount is still considerably less than in the other Baltic States.

Studija Shutters Leaving a Gaping Hole in Latvian Art Criticism

This year marks the end of Latvian visual arts magazine Studija, which means there will no longer be a professional Latvian language publication dedicated to visual arts and culture. From now on, only information about this field will be available through mainstream media. Furthermore, the Normunds Naumanis Annual Art Criticism Award took place in early 2017 and it didn’t have a single nomination from the field of visual arts. It would seem, as such, that art criticism in Latvia is undergoing a severe crisis, which in the long term could lead to a complete de-professionalization in this field.

Miķelis Fišers in Venice

This year the Latvian Pavilion in Venice was curated by Inga Šteimane and featured the work of Miķelis Fišers. The exhibition What Can Go Wrong highlighted the absurdity of the current political climate we are experiencing in Latvia today, underscoring the dystopian sense of our era by combining new age codes of thinking with the aesthetics of horror and fantasy fiction. Art critic Valts Miķelsons described the installation style as “Damien Hirst light,” an apt description if there ever was one.

You’ve Got 1243 Messages Draws Widespread Praise

The exhibition You’ve Got 1243 Messages curated by Kaspars Vanags, Zane Zajanauska and Diana Franssen was definitely a highlight of 2017, in fact, perhaps one of the years best (note: it’s still on view until 4 February 2018) The exhibition focuses on life before the internet and accentuated analogue artefact culture, various creative forms of private communication and items proceeding the virtual age. This informatively and artistically dense exhibition is a rare example of an art event that can be interesting for a wide audience and is highly appraised by the art professionals as well.

Zuzeum Flops, Leading to Widespread Criticism by Art Professionals in Latvia

Whereas the title of the worst exhibition of the year should be bestowed on “TOP of the Top,” which demonstrated superficial selection methods and lack of professional criteria in displaying artwork from the Art Collection of Jānis and Dina Zuzāni, and its forthcoming private contemporary art museum, Zuzeum. For instance, artwork from this collection was grouped in futile categories such as the “coolest, “most expensive” or “largest.” The Zuzāni Art Collection is the major and most substantial private art collection in Latvia, its acquisitions can contest even a national museum, which is why this superficial and anti-intellectual approach towards the future museum, as well as its own collection, shocked many of the art professionals in Latvia. One can only hope the completed Zuzeum project will offer more thorough and well-researched shows.

ABLV Charitable Foundation Announced as Winner of the Corporate Art Awards 2017

And finally, the ABLV Charitable Foundation has been announced as the winner of Corporate Art Awards 2017 in the category XXI Century Art Patron. The Foundation has established itself as a vital supporter of Latvian art and in addition to pledging continuous support to various art events, it is also sponsoring the development of the Museum of Latvian Contemporary Art that is scheduled to open in 2021. During the last few years, the Foundation has supported over 340 projects in total, providing co-financing of more than €4 million.

Top 2017 Slovakia

Jana Németh – Denník N

Nová Synagóga in Žilina

In early 2011, owner of the modern New Synagogue designed by famous architect Peter Behrens, a Jewish community in Žilina started to look for a new tenant to occupy the space. NGO Truc sphérique, the founder of the cultural center Stanica Žilina – Záriečie, decided to do something very courageous. Together they started an ambitious project restoring the New Synagogue and revitalizing it for cultural purposes. In 2017, they have nearly completed all renovations and have opened their doors for public talks, exhibitions, meetings, and art exhibitions. Doing so, they proved that even crazy things are possible if there is a will and vision to go beyond what is expected.

Nová Cvernovka

For almost ten years, many artists, designers, and architects were occupying the old and closed factory in the city center. During these years, they have created a unique atmosphere through cooperation. However, the factory recently got a new owner — private developer YIT who forced them to move out. Each of them could have simply found their own place after the forced eviction, but they came up with a novel solution: to form a new cultural and creative center where they could all continue to work alongside each other. With help from the regional government, they found an old school building that they were able to renovate into more than forty studios. Today Nová Cvernovka boasts an impressive cultural programme and 150 people work and occupy the new location.

Slovak National Gallery

The Slovak National Gallery is undergoing a large reconstruction, meaning that the exhibition space of the institution is now severely limited. However, each of the exhibitions held in 2017 was great. Year by year, the Slovak National Gallery is getting better and more attractive to a wider audience. What’s even more important is that as a public institution, it plays a significant role in society with a very clear attitude even to controversial topics in our history.

Exhibitions of Painter Erik Šille and Sculptor Štefan Papčo at Kunsthalle Bratislava

The story and administration of the Kunsthalle in Bratislava is a bit complicated, however, the exhibition space is one of the most generous in Bratislava. I am very glad that painter Erik Šille and sculptor Štefan Papčo got the opportunity to exhibit their artworks on the large scale that it offers.

Východoslovenská galéria Košice

The reputation of East(ern) Slovak Gallery in Košice, one of the largest public galleries in Slovakia, was desperate three years ago after their search for a new director nearly came up empty. Fortunately, artist and co-founder of independent gallery HIT, Dorota Kenderová, was not discouraged by the possible complications and different administration of a public gallery with a very limited budget. It is evident that after only two years her tenure is a success. The gallery is preparing good for a wide audience and has become a relevant spot for contemporary artists, curators and the local community as a whole.

A Lauded Book about Architect Vladimír Dedeček Comes Out

Today, we are facing the largest construction boom in modern history in Bratislava. Now, we are deciding, what is our city going to look like in the future and talking about the history and architecture from the previous decades is very important in this debate. Vladimir Dedeček, famous architect working mostly in 60s, 70s and 80s, is yet one of the most controversial architects of our history and his work still shapes the public debate about modern architecture. The book (consisting of two books actually) edited and written by Monika Mitášová and co-authors reveals the complexity of urban planning, architecture and the whole interpretation of Dedeček’s buildings which are still very significant in Slovakia. Without books like this, we can not move forward.

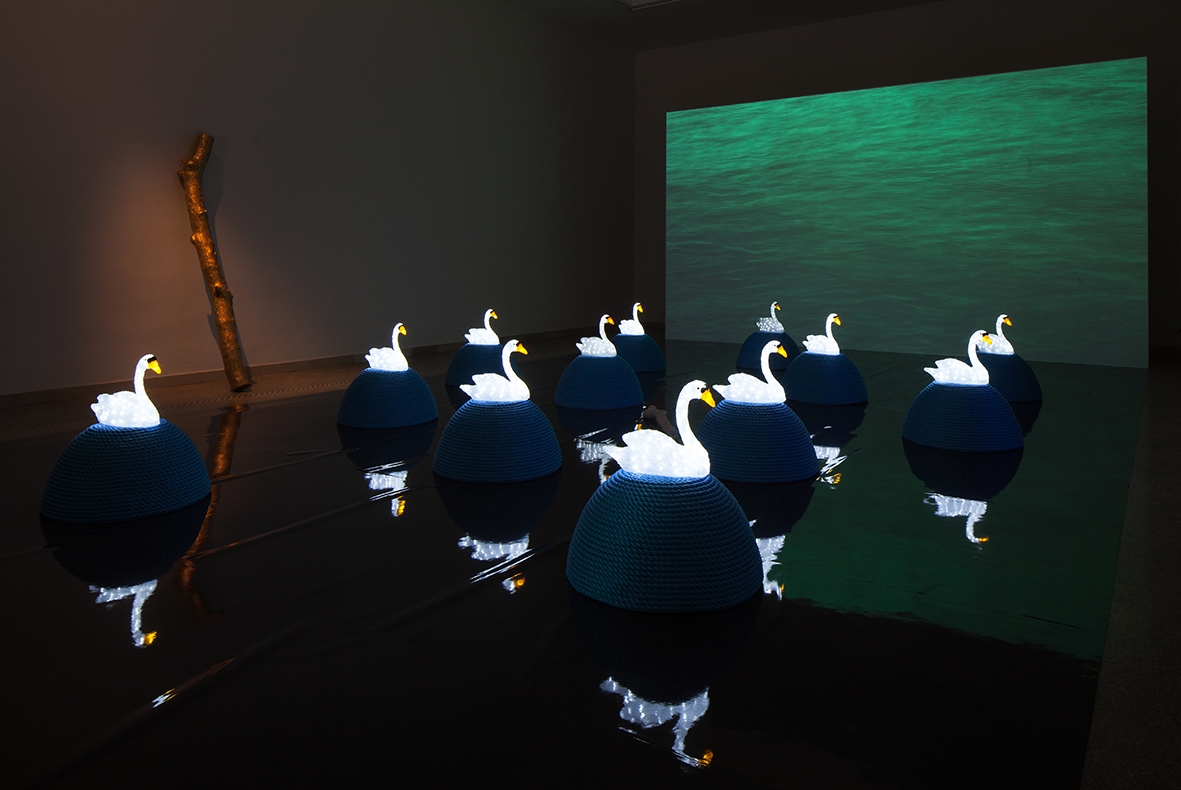

Jana Želibská Representing the Czech and Slovak Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

National pavilions are sometimes in the shade of the main exhibitions, but the installation with the title Swan Song Now of woman artist Jana Želibská (*1941), who is an important representative of action and conceptual art, was the good one. She deserved this opportunity and did the installation with the grace and sense of irony.

Czech Republic in 2017: A Look Back on a Busy Year

Anna Remesova, editor of Artalk.cz

Protests Erupt to Save a Brutalist Building in Prague, A Legacy of the Communist Era

The top events of the year are not always fun and positive, some of them could be alarming, too. That’s why I decided to include in this list the protests against the demolition of the Transgas building, a unique brutalist architectural complex whose design features, such as exposed gas pipes, refer to the national gas importer and transport company delivering gas during Soviet times. The building is now under threat of demolition after a recent decision by the Ministry of Culture refused to name it a cultural heritage site. After the Praha Hotel and Central Telecommunication Building in Dejvice, it is an architectural monument of the Communist regime that Prague wants to wipe from its memory.

An Exhibition on Queer Theory at Meetfactory Gallery

In the Czech Republic, it’s actually very rare to see an exhibition or an art piece based on queer theory, so it was with great pleasure I had a chance to visit the Empire of the Senseless, held at Meetfactory Gallery, which was dedicated to fog, darkness, otherness, senses and feelings. It featured fantastic works by Laboria Cuboniks, Kathy Acker, M Lamar and more, curated by Boris Ondreička.

Kateřina Šedá’s Participatory Projects

This year Kateřina Šedá rippled the art waters twice. Once with a guide through the Roma district in Brno (Brnox – A Guide to Brno’s Bronx, published in 2016), second with her Ukrainian project: Made in Slavutych which was finished this year and provided visibility in the media and in the art world to the topic of Ukrainian migrants and workers in the Czech Republic. Her participatory projects are very ambivalent and therefore make evaluations difficult, generating instead a lot of difficult discussions, awarded the Architect of the Year Award for her efforts in 2017.

Tereza Stejskalová Brings Much Needed Institutional Critique

Tereza Stejskalová organized a series of seminars and readings under the project called “Feminist (art) Institution,” which brought important questions on accessibility, self-reflexivity and inner structures within Czech art institutions to the fore. With the help of many feminists from the Czech Republic and abroad, Stejskalová wrote a Code of practice and invited institutions to participate in it.

New Books Help Shed Light on Cultural Niches in the Czech Republic

A few great books were published this year, among them Apocalypse Me by Jan Zálešák and anthology Filmmakers of the World, Unite! edited by Tereza Stejskalová. Also, the Atlas of Spontaneous Art, dedicated to Art Brut and Folk Art in Czech cities and villages, edited by Pavel Konečný and artist Šimon Kadlčák, was of note. This nicely compiled guide consists of extraordinary art pieces that are free from the market or contemporary artistic practices.

Digitization of Important Czech Archives

Moravian Gallery in Brno made its collection accessible via a new website. It is a step forward in the right direction in helping to open the institution towards accessibility. Another project initiated by Ester Krumbachová, a screenwriter, and director of Czechoslovak New Wave cinema, helped promote the digitization of its archives. The platform ARE prepared an exhibition at Tranzitdisplay Gallery (which is up until 21 February 2018), with her works and pieces from contemporary artists, a conference dedicated to Krumbachová’s life and work, and they are also digitalizing her personal archive which will soon be available.

The City of Prague Ratifies New Policy for Supporting Public Art

In April, the Council of the City Prague ratified the “percent for art policy,” which means that 2% from the budget of each development project commissioned by the city will be deduced to funding and installing public art. This project means a breakthrough for cultural initiatives in the city, while at the same time raising concerns about the quality of future art pieces because of the lack of expert and public discussions.

PLATO Gallery Continues To Develop Interesting New Formats

Some of the art institutions, like PLATO Gallery, are changing their operations. As an experimental “Office for the arts,” PLATO Gallery operates in a provisional space until renovations are complete on a new building they are set to occupy in a few years. Another institution offering progressive and short-term programs, and playing with the format of the exhibition in ways that many other art spaces do not, is Display. Their curators, Zbyněk Baladrán and Zuzana Jakalová, created a series of “multilogues” that consist of talks, events, performances, and discussions avoiding the “one-voice” and the all too often didactic and authoritative format of classic shows.

A Slew of Promising New Galleries and Spaces Emerge

Karlin Studios, INI Gallery and A.M.180 Gallery all moved to new spaces this year. Set between the Žižkov and Karlín districts in Prague, this area promises to become an interesting hub for arts and culture in 2018. A new gallery in Letná opened in 2017, too, called Kurzor Gallery, operated by the Center for Contemporary Art. Kurzor Gallery offers one-year contracts with independent curators who can prepare a series of exhibitions based on their interest and research.

Czech Art Awards Go To Well-Deserving Artists

This year’s awards went to very well-deserved artists. The prize-winner of the prestigious Jindřich Chalupecký Award (for artists younger than 35 years), went to Martin Kohout, whose sleepy and gloomy video, Slides, was recognized by the jury. Artist of the year went to Zbyněk Baladrán, whose influential career was also recognized by the jury, and rightly so. Finally, Tomáš Pospiszyl was awarded the Věra Jirousová Award for established art critics. Here’s to hoping next year the laureates will be all women!

Hungary and the Illiberal State of Cultural Affairs That Was 2017

Gergely Nagy, editor-in-chief for Artportal.hu

This past year in Hungary we have transitioned into perhaps the most illiberal state in all of the EU. Year after year there has not been much to cheer about, which means I could not select only positives into my top 10. Therefore, it’s not a top selection, rather a bottom and top selection. And it’s not even 10. I started to count the good things happening in my field, namely contemporary visual art, and I could hardly recall any. I decided to do a plus and minus entry, reviewing some of the most absurd and bizarre instances of cultural progress and regress in Hungary in 2017. On the minus side, I look back at a few things that show the absurdity and dangerousness of the current situation. While on the plus side, I try to show that there is still an art community here that is capable of doing great things. Take a look, and let’s hope for the best in 2018!

Pros

OFF-Biennale Budapest

The second edition of OFF was the biggest event in the progressive art field this year. Over five weeks, more than a hundred events, exhibitions, screenings, performances, and talks took place. Over 30,000 people attended this year, a success by any measure, all of this without state funding or the support of state-run art institutions. But OFF is not about the numbers and facts, it’s about the effort put in by the collective body that is the independent art scene there. This year had a special thematic focus and a title, Gaudiopolis 2017 – The City of Joy, referring to a children’s republic that, for a brief moment, existed in Budapest after the Second World War, showing an example of how to build something from the brink of ruins. Talking about joy during the post-war era was no easy task, but today it becomes more than a provocation: it becomes a sign of life, giving everyone in the scene a huge lift.

Hajnal Németh’s Leopold Bloom Award

Leopold Bloom is the main character in Ulysses, the infamous novel by James Joyce. His name is perfect for this art award, which is funded by an Irish entrepreneur who lives in Budapest and who loves contemporary art. Every two years there’s an application process and an international jury decides the winner. This year, the Bloom Award went to a visual artist who was brave enough to discover unconventional areas in visual art. Németh was recognized by the jury for experimenting in music and pictures. In 2015, at OFF-Biennale, she presented an opera that was just as strong musically as it was visually. Now she’s re-writing famous pop songs, recording and performing them with an approach that is visually quite artistic. She has been living in Berlin since 2002, but every time she appears in Budapest she leaves behind works that make you think.

Theatre Under House Arrest

Episodes from the History of Dohány Street Apartment Theatre (1972-76)

(Trapéz Gallery, Budapest)

A small gallery exhibits a series of photos about a group of people who did something unexpected under the pressure of the political situation in the 1970s. The story started at a decisive moment when an experimental theatre group was expelled by the authorities from a remote cultural center where they rehearsed and performed in Budapest. By 1972, the group had moved to a big flat located at 20 Dohány Street, where they started something they called “Apartment Theatre.” Together they lived and worked under conspiracy, but opened for those who were seeking events and connections to the art and political underground of the city. By 1976, the whole company left after they were expelled again — now not only from their place, but from the country, and this time for good. Like other artists and political dissidents in the frozen atmosphere of the mid-seventies, they were also handed a one-way immigration passport. They emigrated to Paris, and after to New York, where they first checked in to the Chelsea Hotel, only to find an empty three-story building with a big shop-window on the opposite side of West 23rd Street. This became The Squat Theatre, the home of the company and one of the most inspiring art venues in NYC at the time, where performances and concerts took place in its rooms and in the famous shop-window. These were mostly for those who were willing to look for something unofficial and informal. In an exhibition of their work at Trapéz Gallery in Budapest, images from their formative years in the Dohány Street apartment by Péter Donáth and Géza Kovács are displayed. In this context, the group’s work appears more like a series of art performances rather than experimental theatre. Meanwhile, it shows how a magnificent alliance of people came together with a strong commitment but also with a spontaneous and rather haphazard strategy. In times of repression, private space can be a choice: a shelter, a workshop, a free zone or a meeting point. No wonder that Trapéz felt it’s time to remind us to the group’s amazing story.

Night Blindness by Marcell Esterházy

(acb Gallery, Budapest)

In an exhibition that will surely be regarded as a highlight of his career, Marcell Esterházy presents strong and beautiful works at acb Gallery in Budapest. The show comes to terms with the past of his family and the death of his father, Péter Esterházy, who died in 2016, and was probably one of the most influential writers of recent decades in Hungary. As an opinion maker for lots of people in the country, he had a sense of care and intellectual humor mixed with panache and attitude. Marcell’s exhibition sought to do something with the objects found in the family house and also some of the belongings of his father. In the end, the exhibition ended up looking like an immaterialized and deeply personal set of works. With the wooden books crafted of the tree cut out of the family’s garden, and shaped exactly the size of the volume of books written by Péter, the metal structure of the shapes of the apartments Marcell used to live in and the old dusty black T-shirt found in the attic, the exhibition that transformed into an object I likened to the Shroud of Turin.

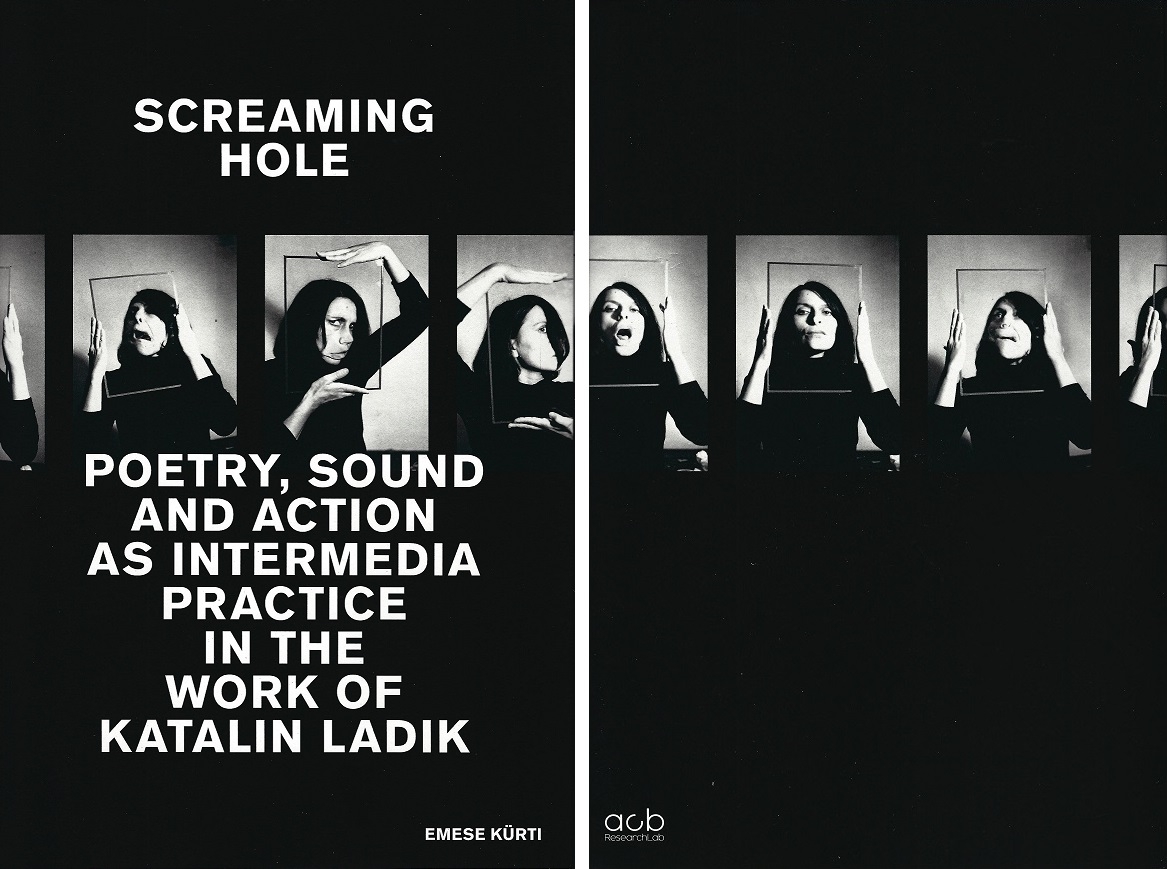

Rediscovery of Dóra Maurer and Katalin Ladik

The rediscovery of artists in Eastern Europe has been one of the most interesting and important developments in recent art history, perhaps none more obvious than in the work of Katalin Ladik, whose works were presented this year at documneta 14 in Kassel and Athens. Starting her career as an actress in the 1960s in former Yugoslavia, Ladik was a brave performer who used her naked body and voice in her works. She became one of the founding members of a strong feminist avant-garde performer scene in the region. The photos of her performances provide fantastic documentation, but also capturing the spirit of her age. In the 1990s only a chosen few knew who she was, but with time has come notoriety. A similar trajectory has befallen artist Dóra Maurer, a widely acclaimed visual artist during her own time but someone who fell into obscurity at the mid-way point in her career. Now 80, she has become an international superstar and cause célèbre.

Minuses

Dismantling the System of Cultural Heritage Management

This is an example of how the illiberal state is functioning and also a tragic process. Though it is a difficult issue to discuss here, the 140-year long history of institutionalized cultural heritage protection and management has ended in Hungary. This past September, an open letter published by professionals of the cultural heritage management department, and also a long article was written by art historian Pál Lővei, appeared in the cultural weekly ÉS, which accurately summarized how the government has effectively dismantled the institutions behind cultural heritage protection, and the likely damages this will cause in the future.

New Rules Against NGOs

The latest modification in the legislation requires non-governmental organizations (NGOs) receiving foreign donations to label themselves as “supported from abroad.” They have to register and also use the label in every public appearance. The government said it is only about transparency so there is nothing to worry about. But the financial resources of NGOs in Hungary have already been transparent: the tax office knew everything and most of the NGOs made public their list of supporters. The law obviously has an impact on the work of art organizations, too. Needless to say, OFF-Biennale also had to register. It’s, of course, the Russian way, a subtle version of the “foreign agent” label that Putin’s government uses for the same NGOs and it’s all part of the anti-Soros campaign… While no one really knows what the next step will be, we are all pretty worried about these new regulatory burdens affecting independent cultural practitioners and institutions.

Artists Declared to Be a “Threat to National Security”

In 2017, a weird series of events showed the state’s adverse reactions to autonomous art. Just to randomly name a few: the state-run “public service” media (which is much like propaganda media these days) like M5 cultural TV channel, did not have a word about what the progressive and critical art scene has produced so far. They picture a totally different art life instead, one in which everything is smooth and nice. The director of the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna banned two artworks by Borsos Lörinc on the opening night of a group exhibition this past June. She never saw these two paintings and was only informed that the artists are playing with the national colors. In fact, in this series of paintings, the artists use black covers on the stripes of the national flag. These are just little stories that show the atmosphere of fear and suspicion currently taking place in the cultural sector. In September, the government declared that two theatre directors as a “threat to national security.” One of them, Márton Gulyás, is an activist, while the other, Árpád Schiling, is an artist with strong political views, and it is likely due to the fact they often demonstrate and organize actions that they were labeled as a “threat.” The declaration was part of the government’s narrative that envisioned this “hot autumn” with violent unrest on the streets of Budapest. The propagandists of the government desperately wanted to point out scapegoats in advance and smartly push them into the role of rebels. However, nothing happened on the streets this autumn. What happened was that the ruling powers crossed a red line again with using verbal weapons directly against individual citizens, many of whom were only exercising their rights to free speech.

Good and Bad on the Romanian Contemporary Art Scene in 2017

Cristina Bogdan, Revista ARTA

- Geta Brătescu at the Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennial – the long due triumph of a revered artist, whose work was properly showcased by the curatorial team headed by Magda Radu. If the Venice Biennial can be used somehow correctly to the advantage of the participants, then worldwide institutional legitimation is definitely the best outcome one can expect – especially if the artist has a body of work which no longer needs questioning and she was also previously an artworld darling, lacking perhaps just this dimension of national representation to become an international household name. An outcome I am just starting to appreciate is that such level of appreciation turns the Romanian artist into an artist, a model difficult to replicate by everyone on the scene, yet desirable if it functions as an incentive to overcome self-colonization, the main scourge of the region.

- Alexandra Pirici ruling the art world, with appearances at every important art event/space of 2017. You can read an interview with her in Revista ARTA in which it is clear that her highly sophisticated blend of political awareness and emotional intelligence is a potent response to current challenges faced by contemporary artists.

- The changes in the Fiscal Code at the end of 2017 affecting independent workers by passing the entire responsibility of the payments of health & pension taxes onto them and away from the employer. The long-term result is the precarization of those working independently (artists, theatre people, but also agricultural workers or taxi drivers), who might choose not to pay their contributions and thus lose the right to health care and state pension. The changes target those with low and medium income, whilst those with high earnings are not too affected. What is properly disgusting is that these neoliberal changes are implemented by a so-called social democrat government. The proper response of the scene is to syndicalise, despite the refusal of the government to allow the creation of unions and syndicates by those who are not employed with a fixed contract. To be continued.

- Issue 3 is coupled with the gradual disappearance of fixed and proper spaces for the independent art scene: by the end of 2017, one can perhaps count 5 important, active and regularly visited such spaces in Bucharest, with venues previously offered by the Artists Union to long-term curatorial & research initiatives being recovered in order to showcase “decorative arts”. By contrast, the flourishing of independent art spaces in Cluj, with witty initiatives such as the pop-up gallery Aici Acolo, can still bring a smile upon our tired faces.

- The constant collaboration between Studio B5 in Târgu Mureș and Magma Contemporary Medium in Sfântu Gheorghe, which over the past couple of years has brought some of the most quirky projects to the fore: anything from intelligent workshops for kids, to playful group shows with unexpected themes and tasks assigned to the participating artists. Especially relevant since the two spaces are located in a region which, despite it boasting a rich cultural life, is otherwise promoted at a national level only for issues related to (fabricated & instrumentalized) ethnic trouble.

- The curatorial programs at Salonul de Proiecte, Tranzit București, Tranzit Iași, ODD, Kinema Ikon in Arad, as well as the public programming at Macaz – as a curator working in different capacities with all of these spaces and knowing them rather intimately, I have to say they are the reason why sweating on the Romanian scene is still fun and makes any sense.

- Marshalling Yard at MNAC (The National Contemporary Art Museum) – one of the laziest takes on showcasing a collection I have ever seen: it basically amounted to clearing the dusty basements (long overdue for a renovation) and chucking all the junk on the ground floor of the museum, where it awaits visitors without any proper explanation, contextualization or even interest. None of the works are properly accessible, however many visitors tend to move pieces around and take selfies with a couple of large pig statues or portraits of the Ceaușescus (since the guards are never aware of what is happening in the labyrinthic space). All this in the context of the museum NOT displaying a permanent collection, NOT having any policy on acquiring contemporary works, and generally NOT showing any sign that it intends to take its history – and the history of Romanian art in general – seriously.

- Since We’re Talking About Mountains, Mihai Iepure-Gorski’s show at Sandwich, brought a smile – call it a rictus – on every local (regional?) artist’s face.

- Art for the People? at The National Art Museum (MNAR), or, how to waste an excellent and much-needed opportunity to discuss the history & legacy of Socialist Realism by allowing historians to curate the show. If MNAR has become known for one thing, then it must be the backward style in display and the curating which manages to obscure almost entirely the research work going into the exhibition. As it is obvious in the interview conducted by Valentina Iancu with curator Monica Enache, the show as conceived by the curator-researcher would have been much more efficient as a book (and in fact, the catalog is a rare and useful tool). Given the importance of the MNAR collection, we are eagerly awaiting the day when they decide to invite curators and perhaps even a team of exhibition designers to work alongside researchers and so-called custodians; perhaps then we will actually start using the museum as tool and not just see it as some obsolete educational attempt designed with no audience in mind.

- Mircea Nicolae turning to art criticism – finally, I can read something else than Revista ARTA.

And a coda: I am still not sure whether the epochal split inside the Paintbrush Factory in Cluj, previously set as the paradigmatic case of artistic entrepreneurship in Romania, is a good or a bad thing – from Bucharest, one cannot properly tell if the issue was money, principles or some sort of existential boredom. In any case, it has made us aware of potential artistic scenarios in the savage times of late capitalism.

TOP 10 Belarus

Tania Arcimovič, editor of pARTisan Magazine

Ruslan Vashkevich, Pass By!

In the spring of 2017, Ruslan Vashkevich brought together a group of blind people to test the malleability of contemporary art for all categories of people. Under the guidance of Vashkevich, they drove across Europe with a final destination in mind, the eponymous Venice Biennale, where rich palaces, modern museums, unique collections, as well as all sorts of gastro-pleasures were awaiting them. The graphics of one of the blind participants, Zarina Lysenkova, were exhibited in the Old Masters Gallery in Dresden, while on their way many improvised exhibitions took place that drew lots of attention. Afterwards, Vashevich’s project was shown during the Moscow Biennale consisting of photo and video documentation combined with artworks by Zarina Lysenkova.

Masha Svyatogor, Kurasoushchyna, My Love

April 6-19, 2017

CECH culture space

Works by Masha Svyatogor are about her complicated relationship with her Belarusian urban roots and cultural environment. She tells her story through personal photographs – childhood pictures, images of her parents and friends, scenery of Minsk’s featureless panel buildings and ponds. Something very typical becomes extraordinary when the subject attributes meaning to her reflections. The artist’s memories of childhood give her food for thought, one that moved us because of how it perfectly that translated into images her thoughts on bare display.

Kryly Khalopa Theatre, Brest Stories Guide Project

The focus of the multimedia project Brest Stories Guide is anti-Semitism and the destruction of Brest Jewish community in 1941-1942. Brest Stories Guide is a project at the intersection of art, tourism and cultural heritage preservation, the result of the co-work of about twenty people, including historians, the experts from Jewish organizations, as well as the best actors of Brest theatres. That makes the project both an innovative tourist and art product and a reliable source for studying the city history.

Minsk. Nonconformism Of The 1980s, NON-Party: the Catalogue’s presentation

March 29, 2017

Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art

Minsk. Nonconformism of the 1980s is the catalog of pARTisan Collection project, which became a result of the same exhibition held two years ago. For the first time, the exhibition presented unique photo and video documents pertaining to Belarusian Informal Art movement, active during the 1980s. The NON-Party became a breeding ground for legendary artists who were heroes of this epoch. Together with Belarusian Climate art group’s Artur Klinau the show repeats a version of a legendary performance he gave in 1989 called Overman’s Spring Song.

NAMES

Collective exhibition

May 11-25, 2017

Korpus Cultural Centre, Minsk

September 15 – October 15, 2017-

Art Space, Viciebsk

October 19 – November 19, 2017

KH Space, Brest

Curated by Anna Karpenko and Antonina Sebur

Artists: Andrei Liankievich, Masha Svyatogor, Sergey Shabohin, Kiril Demchev, Olia Sosnovskaya, Maxim Yasinsky, Hutkasmachnа art group, Alexander Vasukovich and Darya Tsarik, Siarhiei Hudzilin, Antonina Slobodchikova.

10 artists worked for six months with the heroes of the Imena/Names online magazine, which took the form of a series of stories about people’s lives in public. The artists worked with their heroes directly, which often seemed like they were leaving their comfort zone and overcoming cultural stereotypes. It was also the first project that involved several famous Belarusian contemporary artists who helped destroy the stereotypes about inclusion in art.

Anton Sarokin, The Past Is Still Not Over, The Future Has Already Not Come

Solo exhibition curated by Inha Lindarenka and Maria Yashchanka

20 July – 6 August 2017

Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art

Anton Sarokin researches the combinational potential of widely available audio and video materials using found footage from recordings of personal archives, artifacts of pop culture, digital trash, field recordings, and memes, assembling them and creating, in effect, a kind of digital montage. Working as an editor, designer and activist, Sarokin studies what the past can tell us about the present and, indeed, the future. Through research and experimentation with the different media, he uncovers hidden meanings contained within them. In assembling them, he supplements and amplifies them against one another, and mutating them into new forms in the process.

Ostrovets of Culture

Exhibition project about another future of the Belarusian nuclear power plant in Ostrovets

August 23 – September 09, 2017

Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art

Artists and activists involved in the exhibition: Bazinato, Anna Volk (Belarus / Czech Republic), Anastasia Dorofeeva, Oleg Ivchenko (Russia), Veronica Ivashkevich, Anastasia Kozlenok, Valentina Kiseleva, Vladimir Kunz (Russia), Sofia Sadovskaya, Lana Semenas, Irina Suhiy, Max Tref (Belarus / Czech Republic), Victoria Kharitonov, Anna Chistoserdova, Sergei Shabohin, Mila Shidlovskaya, Martha Shcherbakova.

This year artists, architects, and environmentalists decided to appropriate a Belarusian power station, effectively creating and imagining different future possibilities. Ostrovets of culture is a station of science, art, and ecology, which opened on the site of an unfinished nuclear power plant in Ostrovets. Activists went there to create an alternative future in which they believe and want to show us that another future is possible.

Мonth of Photography in Minsk

September-November 2017

Minsk, Hrodna, Brest, Lyntupy

Art director Andrei Liankievich

The Мonth of Photography in Minsk is increasingly one of the most important photo events in the country. Run by a group of artists and managers, this year it presented 16 exhibitions set across 10 venues in a total of 4 Belarusian cities and towns. The program included 11 workshops, lectures and presentations in which foreign and Belarusian speakers were invited to think about the theme of Collectivization.

Mikhail Gulin I Could Do That!

Solo exhibition

November 2 – 26, 2017

Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art

This exhibition was a kind of retrospective of Mikhail Gulin’s actions of the past 12 years. The viewer will see many contextual projects done only once but, in addition, categories of time and place central to the artist’s work were also on display. Working on the street, one can see a strong sense changing political and social conditions. The time of realization is significant, central to understanding the works. For example, when in 2008 he held a performance I’m not gay, the theme of the rights of the LGBT community did not exist in exhibition spaces in Minsk. Thus, 6 years later, the Gulin’s range and diversity of works seemed more relevant than ever.

Ў Gallery Of Contemporary Art Changes Its Location

The Great Epoch Of Belarusian Alternative Culture Has Ended

In November of this year, the legendary Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art moved from praspiekt Niezaliežnasci 37A to another location in Minsk. Next year, the gallery plans on setting up a new location at vulica Kastryčnickaja 19. During many years, this place was one of the most important cultural meeting points in Minsk.

Lithuania: Year in Review

Virginija Januškevičiūtė, Deputy Director at the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) in Vilnus

- Stains and Scratches by Deimantas Narkevičius at the National Gallery of Art, which opened just a couple days before the year came to a close (and will last until February 25, 2018), was to my mind the most important exhibition in Vilnius. It won my heart for the exhibition design by Gintaras Kuginis, we now have an incredibly inspiring place to return to for the next couple months.

- Alvin Lucier’s I am Sitting in a Room (1969) performed at Odeion in Athens, among so many other great encounters during d14 was — for me — composed of.

- PhD dissertation by the artist Darius Žiūra presented at the Vilnius Academy of Arts, a large chunk of which was translated to English and published as an essay How it All Began, in the 2014 catalog of his exhibition SWIM published by the CAC.

- Bill, the new magazine that is pure beauty put together by Julie Peeters.

Deimantas Narkevičius. Stains and Scratches. 2017. Courtesy Deimantas Narkevičius and National Gallery of Art, Vilnius. Photo: Gediminas Savickis

- Lapham’s Quarterly. Did you expect this when you approached me…? Last year more than ever I found things in magazines, or perhaps I just found more magazines, and this is where I need to add — most probably because of my journey of guest-editing the upcoming issue of The Happy Hypocrite, upon the invitation of Maria Fusco, the Bookworks and with Elena Narbutaitė.

- South magazine.

- Jason Dodge and Paul Thek at the Schinkel Pavilion in Berlin. I arrived just when all the works were moved together to the lower level, paintings on newspaper hung above all the trash that took an incredible amount of human effort to get to where it was and what it was.

- Geoffrey Farmer in Venice.

- Radio Athenes.

- The launch of the new issue of F.R. David at Tenderbooks in London, an understated and meticulously staged meditation on preparation and human error.

A look back on a very “Polish” Year

Karolina Plinta & Piotr Policht, editors of Szum Magazine and Blok Magazine

A “Polish” Year in Poland

The year 2017 in Poland was defined by two words: Polishness and feminism. The first, somehow oddly connected to government policy took the form of several exhibitions devoted to the phenomenon of Polishness. In March, at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre of Contemporary Art, there was an exhibition called Late Polishness. Forms of National Identity after 1989, curated by Stach Szabłowski and Ewa Gorządek. The curators had big ambitions, including in the show a vast array of objects including those from the visual arts, film, but also theatre and documentation of performance. The show was strongly criticized from a feminist point of view by art critic Karol Sienkiewicz, but also by Ewa Toniak in Szum, mainly because of its conservatism and its gargantuan size, that saw a total overloading of the exhibition in rooms with works shown badly. But still, this was a more liberal show. A real conservative exhibition opened in Warsaw this past May called Historiofilia. Art and Polish memory, curated by Piotr Bernatowicz and organized by National Center for Culture, an exhibition bringing together Polish right-wing artists. A strong critical character of the exhibition started a discussion in Poland, albeit mostly in right-wing newspapers, as to whether there is even such a thing as ‘right-wing critical art’ in Poland. Last, but not least, this bizarre ‘Polish Year in Poland’ ended with a feminist version of “Late Polishness” in an exhibition called Polish Women, Patriots, Rebels, curated by Izabela Kowalczyk in the Arsenał City Gallery in Poznań. Unfortunately, this show also did not get many good reviews either, proving that left-wing art can be just as bad as right-wing art.

Shocking Polishness In The Theatre

A play called The Course directed by Oliver Frljić at the Powszechny Theatre in Warsaw also laid bare the widespread theme of ‘Polishness’ in 2017. It was planned by the director to be a deliberately controversial show – a spectacle including scenes of a blow-job unto the former Pope, John Paul II, and a scene of cutting the Holy Cross with a chainsaw, forms of provocation that nearly always work in Poland. The show was quickly criticized by right-wing pro-Catholic circles leading to crowds of protesters who gathered in front of the theater before each show, brilliantly playing with Polish hypocrisy.

Selfie-Feminism and #metoo

In the western media selfie-feminism is a hot topic, so it’s been only a matter of time for it to enter Poland. The whole thing started with Zofia Krawiec’s selfie-feminism manifesto, published in Szum this past January. Krawiec did not have to wait long for reactions – while some praised her column, others laughed, and others criticized it vociferously. Including Agata Pyzik, another feminist art critic, who accused Krawiec of peddling ‘false politics’ and self-centeredness, narcissism and promoting soft-porn aesthetics. An exhibition on feminism called Ministry of Internal Affairs. Intimacy as Text curated by Natalia Sielewicz opened this year at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, while a smaller, but still cool exhibition called The Power of Friendship opened at lokal_30 gallery, this one curated by Tomek Pawłowski, a rising star in the Polish art world. Sadly, the subject of feminism this year ended with a stupid quarrel about Iza Kowalczyk’s exhibition in Poznań, and also a Polish version of the #metoo campaign, during which two left-wing journalists were accused of harassment and even rape. It pleased all conservatives and right-wing populists alike but also triggered a broader discussion about procedures in Poland applied to those accused of crimes – whether they should be investigated or whether accusations of sexual assault are enough to warrant a conviction? Opinions on this subject are divided, but as it turns out, the discussion about it has become complicated with emotions on both sides.

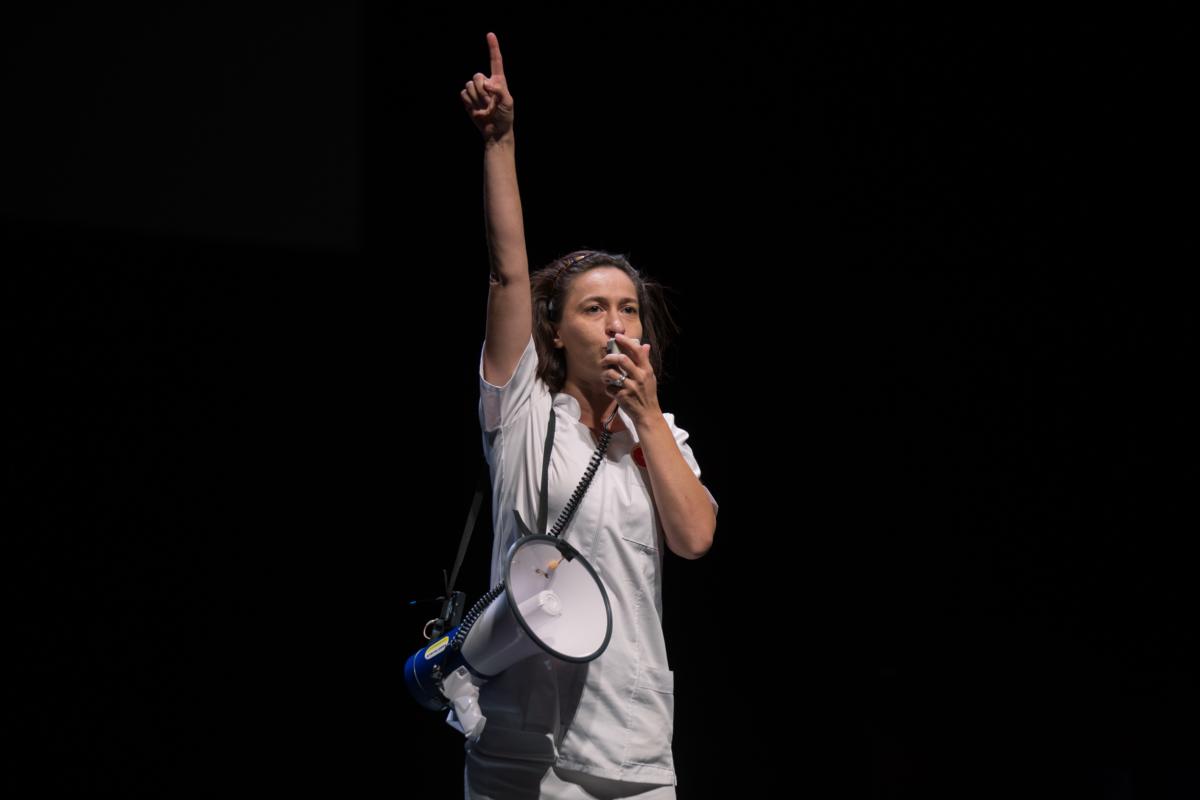

Dominika Olszowy

A few years ago, performance in Poland was associated with something outdated and discredited, but now we experience a kind of renaissance of this genre – a generation of young choreographers conquers theaters and galleries, but visual artists are doing just as well. This year I even enjoyed more performances prepared by visual artists, like Dominika Olszowy, who has prepared some interesting performances this year. In the past, Olszowy usually worked with a team – she co-created a feminist rap duo called Cipedrapsquad, and also a motorcycle gang of artists, named Horsefuckers Moped Club. She is also a creator of an ephemeral gallery SANDRA, showing mostly female artists. In 2017, she mostly worked alone, but with very good results – during summer, in the National Gallery Zachęta, she showed the performance Ego Trip – and it was witty, lyrical and flirting with theatrical tools. She also had, together with young painter Cezary Poniatowski, an exhibition True Romance in Zona Sztuki Aktualnej – a gallery in Szczecin, which was transformed by them into a romantic grotto. In September, she opened her first individual exhibition at the Municipal Art Center (MOS) in Gorzów, which is her hometown. One part of the exhibition was the office of a coffee fortune teller, which foretold the future of coffee grounds. Now she is working as director of Performance TV (PTV) in Centre of Contemporary Art Ujazdowski and, needless to say, we are all waiting impatiently for the first episodes of this artistic TV!

Potencja

Jacek Kuroń’s famous saying “Don’t burn the committees: set up your own” is true for artists as well. Among those who did are three young painters from Kraków: Karolina Jabłońska, Tomasz Kręcicki and Cyryl Polaczek. Together they formed a group and established a gallery named Potencja. 2017 was a big year for them: Potencja organized several shows and had their first group show in Warsaw, in Raster gallery. Even though Kraków is the second biggest city in Poland, it’s gallery scene is rather small so instead of waiting for appreciation to come, Potencja started their own thing. Jabłońska’s, Kręcicki’s and Polaczek’s paintings are playful and intelligent, and they also create a space for equally interesting artists to show their works; amongst others Martyna Czech, a promising young painter given her first solo show in Potencja. Its activity is also a part of the new wave of proliferating artist-run spaces all around Poland, one of the most uplifting phenomena in Polish art world recently.

The Museum on the Vistula

The struggle to preserve the heritage of socialist modernist buildings continues in Poland. One of the victims of local developers was the former temporary location of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, the Emilia Pavilion. Built in the 1960s as a commercial pavilion in which furniture was sold, the building was located in the very centre of Warsaw, close to The Palace of Culture and Science, but finally, in the first half of 2016, the museum had to leave the pavilion which was soon after demolished to make place for yet another corporate building (the construction site still stands empty though). The date of the planned opening of the target building was delayed once again, but last spring the museum moved to yet another temporary location – a pavilion on the banks of the Vistula river. This transition seems to be not only physical but somehow symbolic as well. In a location perfect for Sunday afternoon strollers, MSN seems to focus more on education and entertainment, rather than a critical approach to timely sociopolitical issues. It started the new chapter of its history with a surprisingly classical exhibition dedicated to the figure of mermaid, Warsaw’s symbol, after which came a series of historical exhibitions from the one dedicated to Oskar and Zofia Hansen, two Polish modernist architects, to the one about connections between visual arts and rave culture. The museum also ran a contest for artists to design a piece that would cover its shiny new snow-white pavilion. The winner was Sławomir Pawszak who covered the building with his typical, colorful, decorative abstract painting which is also symptomatic for the turn in museum’s program.

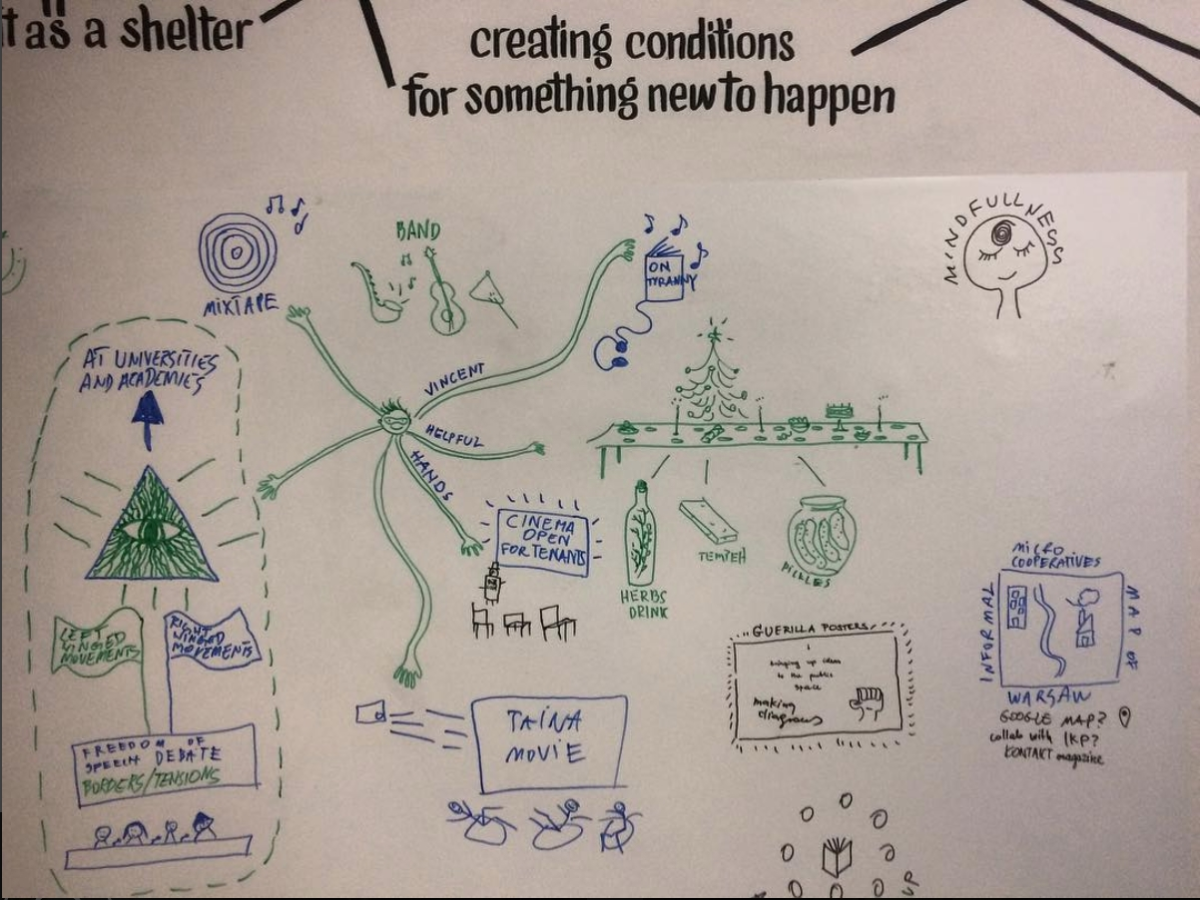

8. Young Triennale in Orońsko

There is a lot of contests for the young artists in Poland right now. Yet, not everyone is willing to participate in a rat race for prestige in the stiff institutional framework. Three young curators, Tomek Pawłowski, Romuald Demidenko and Aurelia Nowak, decided to reflect on this framework within the eight edition of Young Triennale in Orońsko, which they curated. Organized by the Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko, an institution located in a complex of buildings and a park basically in the middle of nowhere, i.e. a small picturesque village in central Poland, the triennial was a minor event couple of years ago. Last year, instead of curating yet another standard exhibition showcasing some works by selected young artists, the new curatorial team decided to completely change the formula of the triennial, proposing a week-long symposium. The exhibition consisted only of documentation of the events that took place during that week; in fact, in the beginning, there was supposed to be no exhibition at all. The whole idea could be seen as a revival of a tradition of symposiums organized in communist Poland by artists, critics, and curators, mostly in the late 60s and 70s in the western part of the country. Back then, these were a response for the lack of proper public institutions focused on contemporary art, and these were the places where the most important debates were held, including the birth of Polish conceptual art. Today, this dusty old formula turned out to be surprisingly fresh because of the exact opposite situation – an ossification of the large institutional machine that has become more of a hindrance than an opportunity for young artists.

Year of the Avant-Garde

In 2016, soon after the ultra-conservative Law and Justice party won a majority in the parliamentary elections, the art world froze in horror when none of the four major contemporary art museums received any money (literally – not a single penny) for their collections. After a while, the decision was changed and some money granted, nevertheless one thing was clear – the new government could cut funding for visual arts at any moment. In 2017, a group of people led by Jarosław Suchan, the director of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, came up with a simple yet clever idea to organize a special program for the symbolic 100th anniversary of Polish avant-garde, to rethink its history and its place in the discourse of national heritage. It comes as no surprise that the government loves celebrating everything connected to national history so as such, the Year of the Avant-Garde was a huge success. However, there were quite a few exhibitions that really moved the discourse forward (most of them in Muzeum Sztuki itself, like Superorganism. The Avant-Garde and the Experience of Nature), and the whole thing from a year’s perspective seems like a missed opportunity. And this year might be even a bit harder to survive – now instead of the avant-garde we’re celebrating a 100th anniversary of Poland’s independence…

(#)Heritage

Speaking of heritage – one of the institutions that do not need to worry about the ministry of culture’s discontent is the National Museum in Kraków. It’s highlight exhibition last year, curated by the museum’s deputy director for academic affairs, Andrzej Szczerski, was called #heritage and presented a very smug take on this historical narrative, showing curious objects from the museum’s collection to illustrate how conservative approaches to Polish history have played out. The hashtag in the title didn’t make it any more modern, quite to the contrary, the exhibition was mocked by the team of organizers of a queer culture festival called Pomada, with artist Karol Radziszewski in the lead. This year the festival’s main exhibition was also entitled Heritage (this time without a hashtag) and housed in a small rented space in the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw. Without state funding, relying on their own commitment and crowdfunding money, organizers of Pomada made a show composed of art pieces and lots of extravagant artifacts (like writer Jacek Dehnel’s walking stick), managing to quite effectively broaden the discourse on the history of Polish queer culture.

Adrift Further East: Dispatches from 2017

Curator and critic Dorian Batycka reflects on 2017, a year that saw him pivot away from Western Europe in search of aesthetics less familiar…

January – Singapore

2017 started off with an interesting trip to Singapore for the tenth edition of the Singapore Biennale. To my surprise, it was a stimulating experience, my first in the Asian city-state. Though Singapore is often depicted as a state with rampant censorship, to my surprise all of the curators and artists I met there were more than willing to speak frankly with me about the challenging issues they face. Many of them opened up and shared with me very personal details of how life within the former British colony is changing, including how contemporary art from the region is slowly starting to form a crucial pillar of public debate, often in spite of overt forms of government control. The year started off with a lesson: that in places where regimes actively practice censorship, there are nearly always people working towards and willing to bravely circumvent it.

February – Lombok, Indonesia

Psirputih is a Pemenang-based egalitarian nonprofit organization located in North Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. The group focuses on bringing emerging forms of media literacy, art and sociocultural studies to the small island community. This past February, Psirputih hosted about a dozen or so artists and writers (myself included) who presented work at the center. Among the most interesting discoveries for me was a collective called LifePatch, a citizen-led initiative at the intersection of art, science and technology, with members from across Indonesia and abroad, all of whom I discovered have a varied approach to digital media: including one project that hooked up sensors to an active volcano that could be accessed remotely, translating the frequencies of the movement of the tectonic plates into audio.

March –Prague, Czech Republic

Ai Weiwei gave some monumental justice to the refugee crisis this past year, perhaps none bigger than the massive rubber boat installation at the National Gallery in Prague. You’ve got to hand it to Ai, he’s certainly not afraid of confronting the world’s most urgent social issues, even, and perhaps in spite of, all the criticism he gets for it.

April – Athens, Greece

I discovered Artists at Risk in Athens as a collateral event outside documenta 14, where they set up a pavilion showcasing work by Pınar Öğrenci, Erkan Özgen and Issa Touma. Artists at Risk is best defined somewhere in between a human rights organization, a residency and a curatorial platform. The mandate of the organization is to provide a safe-haven for artists who face an acute political threat, often simply for artistic activities. Founded by Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolsky, two curators and cultural programmers with extensive international experience working with politically engaged art, Artists at Risk works towards facilitating safe passage into “AR-Safe Haven Residencies” with a focus on long-term projects, thereby bringing a sense of stability back to the lives of artists.

May – Moscow, Russia

What’s a trip to Russia without a splash of cultural censorship? This past May, I spent time in Moscow during which I covered the arrest and detainment of Kirill Serebrennikov, director of one of Moscow’s largest theaters, the Gogol. And yet, the discovery of Simon Mraz, an Austrian cultural attaché based in Moscow, rounded out my experience quite well. An enigmatic curator and collector with a penchant for oddball artists, Mraz’s residence, which doubles as a salon for showing his expansive collection, is located only a stone’s throw from the Kremlin, where he shows a bevy of artists often overlooked (or censored?) by official state institutions.

June & July – Riga, Latvia & Tallinn, Estonia

A three-week residency at kim? in Riga brought me immediately after to Tallinn in Estonia, where I began to connect the dots of a little-known area of research called “Baltic Postcolonialism.” Over the course of my Baltic drifts, I started to wonder about how other post-Soviet bloc countries are starting to re-define their relationship to the former imperial center. Questions that I imagine will remain critically important for me into 2018 and beyond.

August – Sokołowsko / Białowieża, Poland

Ewa Partum’s black umbrellas outside the Brehmer Sanatorium during the 7th International Festival of Ephemeral Art in Sokołowsko was a definite highlight for me this summer. The work took an original quote from street protests that erupted in Poland in 2016, during the popular struggle for women’s rights. “You will take away our freedom of decision, we will take away your power,” the work read.

In Białowieża, I visited protesters who remain in a fierce battle with national authorities and private logging companies struggling to protect one of Europe’s last remaining ancient forests. The forest is a UNESCO heritage site, which I got to see first hand, and where artists have taken to using creative forms of civil disobedience to disrupt the loggers. Solidarity!

September – Istanbul, Turkey

My two weeks in Istanbul were supposedly spent covering the Istanbul Biennial, but mostly chilling at the “trap spot,” an emerging artist-run center in Beyoğlu called OJ, hanging out with Fred Wilson, whom from afar I discovered looks remarkably like the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato, drinking way too much Rakī, schmoozing till the morning, and seeing some incredible art. I love Turkey and the energy there, it’s really too bad the government is so fucked up.

October – Warsaw, Poland

Gotong Royong. Things We Do Together opened at the Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art this past October. I got to develop a few new works including Kineticoin (2017) (together with Scott Horlacher) for the show, which is basically an experimental cryptocurrency and blockchain for plausible art worlds. In addition, I put together a performance series one of which was called (-̮̮-) 2GETHER, featuring Justin Francis Kennedy, Lara Joy Evans, Kasia Wolinska and Ashiq Khondker. The exhibition closes January 28th, so there is still time to check it out if you’re passing through Warsaw.

November – Krakow, Poland

Bunkier Sztuki put together a fantastic show called New Region of the World curated by Anna Bargiel and Olga Stanisławska. The exhibition took up the subject of colonization in the global south, but in a way that felt timely and necessary, especially given the mounting unease over rising specters of nationalism in Poland today. The show featured few newly commissioned pieces, albeit did present a fairly thorough overview of artists who have tackled variable dimensions of postcoloniality over the past several decades. I sincerely hope to see more exhibitions in Central and Eastern Europe that take up the challenging, yet necessary, theme of postcolonialism.

December – Kielce, Poland

Firmament Festival an intimate small two-night experimental music festival in Kielce, southern Poland. The free festival this year featured two acts I found superb, Mert + Ter and ambient downtempo artist PTR1.