Introduction

This article presents the conclusions of research into Belarusian art criticism and art journalism, conducted by a group from the European Education and Research Centre (Vilnius) in 2022 and 2023. We have decided to focus on art criticism and journalism because of their importance in the field. Art critics and art journalists are proactive players involved in structuring and demarcating the arts. They document, archive, and “highlight” a range of vital artistic events and phenomena, while creating and maintaining discourses that offer more than simply “feedback” for artists. Using explanatory models and symbolic markers, they can shape the art field and determine the image of Belarusian art for audiences at home and abroad.

We feel that this role of art critics and art journalists has been systematically devalued in public discourse and research on the Belarusian arts. As a result, art criticism and journalism in Belarus are little-studied, often invisible aspects of the art world, reduced to a servile, subordinate, even menial function. We propose to examine the scope of art criticism and journalism more broadly, as we regard art critics and journalists as actors not only on the Belarusian art scene, but also in public space. This is because art critics and journalists work to reveal the meanings, values, and concepts that creators have embedded in their works and exhibitions. They strive to provide “translations” from the language of art and initiate wider audiences into pondering and discussing art works and their underlying social reality models and issues. Art critics and journalists operate in public space via thematic or generalised publications in the media, social media, specialised press, and catalogues. In Belarus, they are as visible as sociologists, philosophers, political scientists, and experts from adjacent fields. Additionally, many art critics work in those professions in parallel to their arts and humanities activities.

Our study confirms the hypothesis that art criticism, curating, research, and artistic activities often overlap among players in the Belarusian art field. This makes it impossible to conclusively position critics as coming from “outside” or “above” artistic practice. After all, their activity is flexible, fluid, and they are fully entitled to move around within the field, express their opinions, and take up various roles and positions. In that respect, art critics and journalists have possibly the greatest communication potential of all actors on the scene. That flexibility and ability to raise thematic/challenging discussion topics even attracts artists, who occasionally dabble in art criticism themselves.

As mentioned above, art critics and journalists are also important in the public eye due to their inherently responsible role as mediators with a symbolic ability to map out cultural trends. Of course, myriad factors mould the discourse on culture and the arts, including education, experience, and each writer’s own attitude to the socio-political context. So, to comprehend the specifics and ongoing role of Belarusian art criticism and journalism, with all their problems and contradictions, we must delve into the very existence of the Belarusian art field. We must examine its structure; how it functions; the segments into which it has been divided at various times; its predominant discursive strategies, and why they have prevailed. We need to outline the historical context of our research, since it directly affects art criticism and journalism, and contemporary art in Belarus. We will also explore the links between the Belarusian socio-political context and artistic discourse, in line with the subject of our research: the influence that socio-political context has had on Belarusian art criticism and journalism, and how it has affected content, values, discourse, and infrastructure.

This is highly relevant, for several reasons. Firstly, Belarusian art criticism and journalism have never been researched in this way. Secondly, the Belarusian art world and society have both faced unprecedented challenges in the past three years, following the 2020 protests in Belarus and Russia’s war in Ukraine. Every aspect of life in the country is governed by a strict hierarchical pyramid, and the public sphere is harshly regulated by restrictions, censorship, and oppression. Due to all of these factors, this text is written from the standpoint of our study group, not personally. We have also avoided direct quotes, so as to guarantee the confidentiality of our interviewees.

The first section of our research is an analytical discussion of the state art press, and individual articles from both state and independent print and online media. The second section sets out to study the experiences and musings of art critics, interviewing writers who have covered the Belarusian arts for various publications. We felt compelled to go beyond personal preferences and attitudes to present the broadest view of people’s experiences and opinions regarding art criticism.

Our research consisted of interviews with 19 people (14 women, 5 men), who write or have written professionally about the Belarusian arts. There were no formal restrictions on the regularity, amount, or genre of texts due to the specifics of Belarusian media and the lack of art-related publications (another key area of this research). Our interviewees had written for state or independent publications, or both. We also established that – due to the structure of the Belarusian art field – our interviewees felt that being an art critic was more of a role than a profession (discussed in more detail below). Consequently, our interviewees write about art while doubling as artists, curators, public intellectuals, journalists, etc.

“Convenient” art criticism and journalism

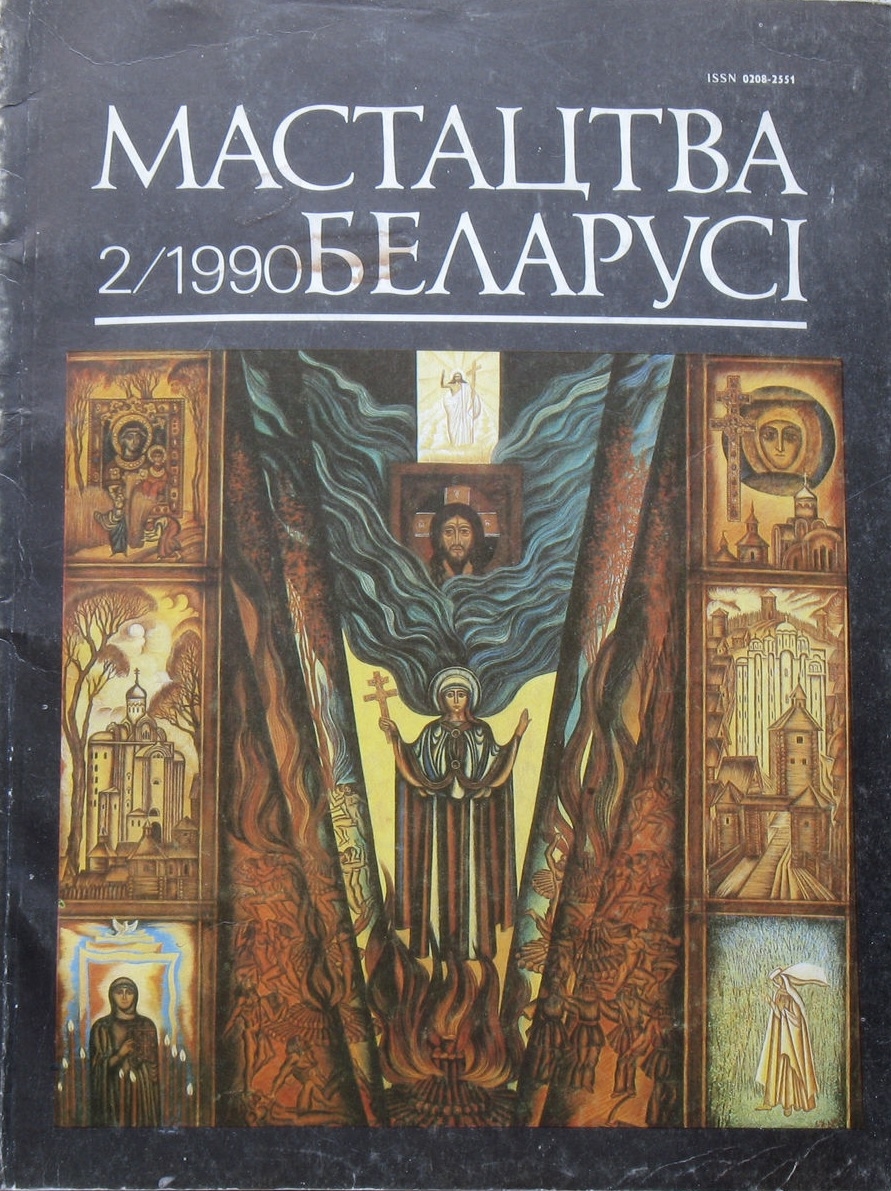

In order to discuss the specifics of Belarusian art criticism and journalism, we should provide some historical background. Prior to the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, the former Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) had several arts publications whose general tone defined what “ought to be” said and written about art. For example, the magazine Mastactva Belarusi (later shortened to Mastactva), published monthly since 1983, and the weekly newspaper Literatura i Mastactva, since 1932. Both are organs of the Byelorussian Ministries of Information and Culture and the pro-state Writers’ Union, which dictate their ideology. They both transmitted a Soviet artistic discourse full of Communist propagandist rhetorical devices for the collective socialist utopia, expressed in clichéd journalese. One typical Mastactva Belarusi article from the 1980s reads: “The fine arts – with which I am directly concerned, being a painter and a department head at the BSSR Ministry of Culture – are currently on the front lines of the battle for people’s hearts and minds”.[1]

The artists and events discussed in 1980s’ BSSR art publications were selected for their allegiance to state institutions, and if they toed the official line. State publications and their writers would shun artists who were non-conformists and/or whose works were in tune with world trends. The same applied to artists marginalised by state institutions for not accepting “orders” from above.

In the 1980s, Mastactva Belarusi considered Belarusian art within the geographical context of the Soviet Union, where the Moscow art world was held up as the reference for all Soviet art. One interviewee remarked that, during the BSSR period, it was only possible to defend an arts thesis on topics relating to folk art. If a student wished to defend art history and/or theory, their topic had to be approved in advance, and/or their thesis had to be defended in Moscow, Leningrad, or Kyiv. This was another example of how dependent and provincial the BSSR was in the 1980s, even in terms of “state management” of the arts and artistic discourse.

Judging by the articles in Mastactva Belarusi and Mastactva, one might think the instruments for analysing Soviet art works were limited to formal descriptions of method and searches for metaphysical subtexts or patriotic, ideological messages. These texts never took an interdisciplinary approach or analysed the context in which works were created. The writers never adopted a critical stance or applied any critical theories (gender, neo-Marxist, post-colonial, institutional, etc.). Their discourse primarily revolved around concepts such as genius, talent, creators, continuity, exquisite mastery, colour or graphic composition, etc. Such texts were brimming with superlative adjectives, poetic metaphors, ideological clichés, and long lists of artists’ services to the country, in a style that could be termed lyrical-ideological pathos. Here are a few typical linguistic constructions from 1980s’ publications: “a historical-revolutionary painting”, “unrepeatable works”, “expresses the human spirit”, “glorifying the Belarusian landscape in its spring attire”, “the ideological-professional level of creators”, “the formation of a new humanity”, “a harmonically developed, socially relevant personality”, “creating an aesthetic environment”, “the burgeoning of the nation’s soul”, “a symphony of national artistic cultures”, “eternal, spiritual self-expression”, “fraternal Eastern Slavic nations”, “a fruit of the spiritual life of the national character”, “accordance with their inner world”, “depth of ideas”, “the historical-spiritual culture of the nations”, “landscapes filled with pristine purity”, “the search for inner artistic integrity and harmony”, and so on.

In those days, art critics and journalists would analyse and describe art more as a visual phenomenon that existed merely to endorse the country’s ideological trajectory and patriarchal, authoritarian values. Publications contained advertisements and descriptions of works and exhibitions, accompanied by verbose ruminations, yet avoided referring to contemporary world trends and were never interdisciplinary. Typical titles of art-related texts are a vivid illustration: “Harmony of the material and the spiritual”, “[Ideological] appeal and image. Notes on the condition of visual agitprop”, “Figurativeness and realism”, “When you look at the world with love”, “Of my dreams war has stripped me”, “Art must please both the artist and others”, “National art and schools”, “We are building Communism”, “Educating our creative successors”, “The bronze wings of victory”, “Reviews of artistic ideals”, “The living breath of nature”, “Unearthing talents”, or “The high tribune of art”.

Up until perestroika, Belarusian art publications cultivated a discourse that left no room for problematic issues, since – officially – the society had no such problems. It resulted in harmless, “convenient” art, art criticism and journalism; the kind that never sparked debates, discussions or questions, and required no audiences, diversity, or personal interpretations. Soviet writings on art produced a homogeneous, unvarying, authoritarian discourse that excluded all possibility of expressing alternative points of view.

“Intuitive” art criticism and journalism

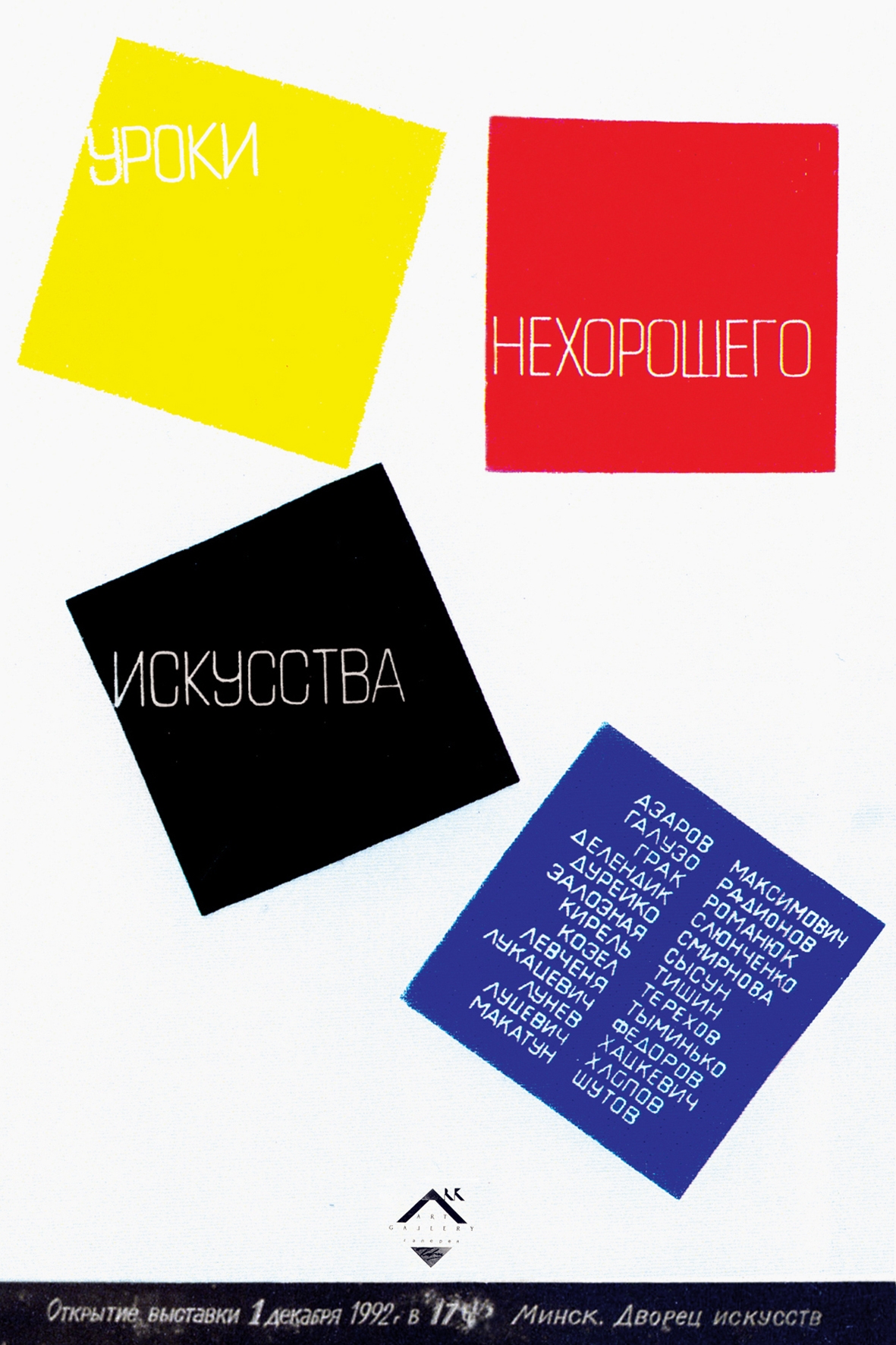

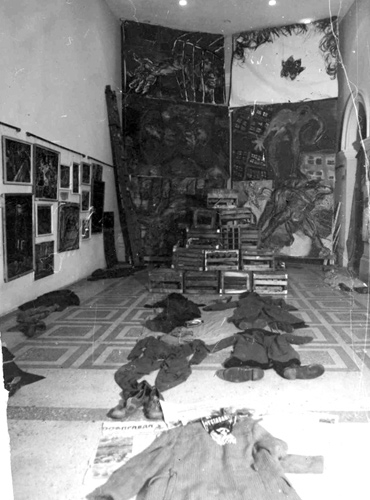

Before the collapse of the USSR, however, a more active alternative art world emerged in the mid-1980s. New artistic practices and collectives started to appear and break with tradition, e.g., the Nemiga-17 and Byelorusskiy Klimat art groups in Minsk, and Solyanye Sklady in Vitebsk. After the USSR crumbled in 1991, the country underwent more profound changes that also affected the arts. Formerly “inconvenient”, non-conformist artists were able to organise large exhibitions and performances, e.g., Artur Klinau’s apartment exhibition in 1984, or the Bad Art Exhibition in Minsk, curated by Igor Tishin in 1992, etc.

Once the USSR had broken up, foreign donors, such as the Soros Foundation, offered the country support for numerous cultural projects, including the Belarusian arts. Minsk’s first contemporary art gallery, Sixth Line, opened in 1991, thanks to the plans and efforts of young Belarusian curators and artists (founders Viktor Petrov and Ales Taranovich; directors Alena Doroshevich, Irina Bigday and Egor Yermakov; curator Olga Kopyonkina; etc.). Sixth Line gave the Minsk independent art scene opportunities to develop, and similar exhibition spaces opened in other cities. For instance, apart from Solyanye Sklady in Vitebsk, a group of artists led by and Vasiliy Vasilev launched the independent In‑formation exhibition project in 1994. These alternative, non-state venues became hubs for a new artistic community, and the very first lectures and debates on contemporary art were held there (although the term “contemporary art” was not yet in use).

In the 1980s and early-1990s, most Belarusian artists, critics and journalists’ understanding and mastery of the language of contemporary art were guided by intuition, as there were no institutions capable of providing relevant education. Some interviewees who were writing about art in the 1990s were aware that the critical lexicon, approaches, and methods of the time were outdated and inapplicable to contemporary art. Here is an example of that “obsolescent” discourse, taken from an article by I. Koronevskaya, attempting to describe new Belarusian art processes using Soviet newspaper clichés: “In recent years, traditional (‘museum’) art forms have been supplanted by innovative ones, such as performance and installations, which have grown out of scenography and the decorative arts. Not only have they hijacked the ascribed functions of painting and sculpture, they have also harnessed the ‘high arts’ for their own ends by actively incorporating features from those genres, and resolutely continuing to conquer ever-new positions in the artistic process, which feels the need to be enriched with new means of expression”.[2]

To partially compensate for their lack of terminology and education in contemporary art criticism and journalism, our interviewees would actively share and translate foreign art magazines. In their opinion, even most of the specialised universities and institutions for art professionals were incapable of providing an education in contemporary art criticism or practice, as the teaching staff did not possess the relevant knowledge and competence. The only exception our interviewees mentioned was the European Humanities University, which opened in Minsk in 1992.

So, the country found itself in an incongruous situation in the 1990s. Although changes were underway in the arts and culture, alongside political and economic freedom unheard of pre-1991, with foreign foundations and investors willing to develop Belarusian culture, no radical changes occurred in art criticism and journalism. No important, lasting non-state publications capable of generating and promoting a new artistic discourse ever appeared, and the issue of modern educational standards for art criticism, art journalism, and contemporary art was never addressed. Publications which had inherited the Soviet artistic discourse tried to reformat themselves and write about new Belarusian art (which they termed “innovative”). Their articles included “contemporary art”, but were marred by ignorance of the subject and its terminology. Nevertheless, from 1990 onwards, the number of references to governmental edicts and the ideological agenda in Mastactva Belarusi and Mastactva decreased, and its writers actually began to consider the role of artists. After the mid-1990s, articles on foreign arts and photography were widespread. New terms appeared (e.g., “performance”, “installation”, “conceptual art”), together with translated texts by foreign critics (e.g., A. D. Coleman and Cleanth Brooks). Official publications regularly raised the issue of renewing Belarusian culture, and sought to understand why its national features had been eroded: “Due to the protracted dominance of the theory of the merging of nations, and the language dying out, the culture has lost its national basis, especially its inter-generational, ethno-cultural connections. Use of the Belarusian language has dwindled, leading to reduced interest in folklore, national arts and crafts. […] So far, this debelarusification process is unstoppable. Belarus is clearly more denationalised than any other Soviet republic”.[3]

So, one could say that, despite articulating vital issues, using new terminology, and printing translated foreign articles, none of the state art publications of the 1990s ever shook off the Soviet artistic legacy. Their texts resembled essays, containing formal approaches and descriptive elements intermingled with a literary component. Art texts were interspersed with numerous advertisements, stories and interviews about artists’ lives, and articles on historic artists. Meanwhile, the themes of World War II, spirituality, and Soviet traditions never went out of fashion. In short, there were no truly independent art publications throughout this period.

The space for potentially developing culture, the arts, and art criticism is “reset”

Unfortunately, despite the evolving socio-political situation of the late 1990s, arts initiatives and activity were in decline, along with the development of Belarusian contemporary arts.

This was due to several factors. Firstly, the state’s desire to revive the paternalistic Soviet societal model, regulate all areas of society, and banish private initiative and foreign influence. By the late 1990s, the foreign foundations supporting cultural and social projects had been expelled from the country, alternative exhibition spaces were closed down, and the number of private educational institutions was cut. Paltry state subsidies for culture and the arts were reserved for selected “convenient” actors and institutions, to bolster the monotonous political agenda. During this period, Artur Klinau (a Belarusian artist, creator, and editor-in-chief of the journal pARTisan) devised a concept of specific “partisan” tactics – adopted by Belarusian artists as the only possible means of survival in an environment where artists are simply not in demand.[4]

Secondly, the alternative and official (state) art scenes in Belarus were contrasted in the 1980s and 1990s. The former was represented by abstract painting, photography, and one of the most widespread new art forms – performance; the latter was represented by traditional art forms. Thirdly, although unofficial arts and culture were developing, there was no well-balanced contemporary art world with the relevant artistic practices and professionals. Our interviewees remarked on several negative points that “reset” the art scene: many independent artists moved abroad in the late 1990s; a lot of writers resigned from state art publications; and there were no independent art publications, and very few exhibition venues.

All the above left the dominant “Soviet legacy” art publications ploughing on with no radical shift towards contemporary critical discourse and content. Our interviewees felt that this was due to the inability to institutionalise art criticism and journalism, stagnation in the arts education system, and the unreformed, inert publications themselves.

The early 2000s – the era of enthusiasm

By 2004–2006, the independent Belarusian arts had almost vanished from public view. In alternative art circles, this period was dubbed the “reset”, characterised by a lack of variety and notable events in the art space, with the alternative segment sorely under-represented. There were also very few art critics and journalists to record, describe, and analyse the processes occurring in the art world, including unofficial, so-called “inconvenient” art. Browsing through the state art press of the early 2000s, the chosen themes were “harmless”. Critical texts on independent art hardly ever circulated to a wider audience, leaving the next generation of art audiences and activists unable to learn about Belarusian contemporary art – past or present – from those publications. This information “reset” made Artur Klinau’s “partisan tactics” an essential means for the independent art scene to exist and maintain active communication.

So, from 2004 onwards, this seemingly invisible, “partisan” existence grew into a tangible struggle for symbolic artistic capital between the state and alternative camps. The private Podzemka gallery in Minsk (directors Anna Chistoserdova and Valentina Kiselyova) was crucial during this period. It helped consolidate the unofficial art scene, provided opportunities for art curators, and stimulated contemporary Belarusian artistic and critical activity, serving as a venue for contemporary art exhibitions, seminars, and discussions. In 2009, the Podzemka project expanded into the alternative Ў Gallery for contemporary art, a major hub that would attract a wide range of art professionals and audiences for the next decade.

The increasingly active alternative art scene also spawned a variety of independent media. The pioneering journal pARTisan (founded by Artur Klinau in 2002) was devoted to contemporary Belarusian independent culture and arts. Numerous related publications appeared between 2008 and 2015, including the online magazine Novaya Evropa (culture and arts section), the Art Aktivist portal, and the leading photography portal ZНЯТА. These boosted the development of Belarusian art criticism and journalism, bringing them increasingly up to date.

Thanks to their enthusiastic, professional editors and founders, and their focus on contemporary art journalism and criticism, these websites and publications were the first to publish articles on vital issues surrounding the art scene and market in Belarus and worldwide. A few sample titles demonstrate the scope of themes covered by the non-state media: “Notes on the 55th Venice Biennale”, “Sit and watch. On the possibility of cultural capitulation”. “Official cultural policy in Belarus, 2013. What will it be like?”, “Personal: on radical art”, “Artists in Belarus confined within their own little world”, “Marina Naprushkina: when people not only realise, but also shout out loud that the emperor has no clothes on”, etc.

Independent publications popularised the concept and aims of contemporary art, writing about socio-political themes and how art can be interpreted not only formally, but also from feminist, post-Marxist, or post-colonial viewpoints, for example. They also published lectures and summaries of open discussions and round-table meetings. Another vital aspect was the publication of translated and original articles by foreign art critics and journalists.

Thus, one can say that the arts and the language of criticism in Belarus expanded and developed from around 2006, and new art critics and journalists found a space to express themselves via independent publications and portals. Unfortunately, the education offered by arts institutions and journalism faculties never evolved, so new writers either came from other humanities disciplines (philosophy, history, sociology, cultural studies, etc.), or had to learn as they went along. Alternative art criticism and journalism certainly developed in the country thanks to people who had been educated abroad, which enhanced the contemporary art discourse of independent publications.

The growth, development, and consolidation of the unofficial art scene (including art criticism and journalism) demonstrated just how distinct it was from official, pro-state art. During that period, the main task for artists, curators, and independent critics was to implant Belarusian alternative art into the region’s art history. Meanwhile, official media rhetoric continued to ignore numerous unofficial art events. The term “contemporary art” was widely misconstrued, as the public tended to understand it chronologically, not in terms of content, which led to many artists being excluded from the annals of Belarusian art history. That distinction was explored in a major, wide-ranging project, Zero Radius. Art Ontology of the 00s, which ran from 2011 to 2013. Curated by Ruslan Vashkevich, Olga Shparaga and Oksana Zhgirovskaya, it analysed Belarusian contemporary art between 2000 and 2010, and resulted in an exhibition and the first-ever analytical book on Belarusian contemporary art. Meanwhile, the monthly Vitebskiy Kvadrat was published in 2015, focusing on the non-conformist, independent art scenes in Vitebsk and Minsk from 1997–2000.

The Gendernyy Marshrut portal proved crucial for discussing gender issues in all walks of life (including the arts). Important alternative photo art projects (such as Photography Month and the regular World Press Photo exhibitions in Minsk) allowed audiences to broaden their knowledge of contemporary photography. There was also a gradual trend towards decentralising contemporary art. For example, the Kryly Khalopa independent cultural centre in the regional city of Brest.

One might say that increased activity in the alternative arts, new independent publications and online platforms, and the first research into Belarusian contemporary art finally allowed the country to define its contemporary art field. The alternative scene emerged from the underground and acquired a wider audience. Independent artists, critics, and curators could no longer be excluded from Belarusian art history. Our interviewees felt they had played a dual role as art critics and journalists in those days. Some regarded themselves as “chroniclers” and “archivists” on a mission to document artistic events and popularise art. Others stressed the importance of analysing and criticising art in order to articulate the context and outline current artistic trends.

A second “reset”?

We called the period prior to 2015 the era of enthusiasm, when the independent art scene put maximum effort into reinforcing its symbolic capital. Yet its position was still unstable, as it simply lacked funds and infrastructure in the struggle against state dominance. At some point, everyone connected to the independent arts faced the same questions: Should they remain visible and centralised, but always be left out of the wider art discourse as a result? Should they allow themselves to be censored for exhibitions and state publications? Should they work for meagre honoraria, or seek other means to achieve their goals?

Consequently, from 2000 to 2015, the Belarusian arts were still dependent on state policy, and their various segments remained unconsolidated. As the philosopher and researcher Olga Shparaga remarked: “Otherness is also disregarded – especially ‘Other’ artists, but also critics and audiences […], which renders solidarity in the ‘art field’ impossible, meaning it will have no chance to assert its autonomy from the state”. “In Belarus, the collapse of the socialist cultural model did not result in the demise of Soviet institutionalised, centralised management (via the Ministry of Culture), the Artists’ Union, or even the state commissioning system”.[5]

Once again, the independent sector was stuck on “pause”, but can it be called a “reset”? The sheer enthusiasm that had been invested in bringing Belarusian contemporary art up to date and keeping it active proved insufficient. Its activity tapered off due to a shortage of funds and institutional resources. The lack of alternative press, independent galleries, and a developed art market all curbed artistic diversity. Formerly active media (Novaya Evropa, pARTisan, Art Aktivist) closed down, and the photography portal ZНЯТА was sold.

After 2015, the independent sector began to fragment, splintering into mini-groups engaged in different tasks. These communities are varied and rarely collaborate on joint projects. The sector has also become decentralised. Our interviewees mentioned several reasons for this: emotional “burnout” on the alternative scene due to a lack of symbolic and financial support; no state or commercial funds for unofficial art; a shortage of human resources; and the fact that contemporary art and criticism are not taught at professional educational institutions.

This precarious situation for independent artists, curators, and art critics is a serious problem for the Belarusian arts in general. Without regular support from major players (the state and business), they are on shaky ground, with no guarantees. The lack of exhibition space and art publications has led to a negative, competitive atmosphere that favours the official art world. Art has been severed from business, so professional artists, curators, and critics are marginalised and forced to exist from “project to project” and “commission to commission”, or to combine their artistic identity with other gainful employment. Another vital aspect is gender inequality: there are at least twice as many women writing about art than women artists. Many of our female interviewees noted that even the alternative art scene exhibits a form of hierarchy. Male artists often regard the work of female critics as secondary and inferior to that of male artists.

As the alternative art scene grew weaker, the rhetoric of state publications continued to support “convenient journalism”, applying censorship to avoid discussing “problematic” artists and burning issues. Some interviewees described how state publications even censor European artists (according to a blacklist of countries) and any comparative analysis of Belarusian and foreign art. Despite the censorship, however, in recent decades state publications have also run articles on art events that dealt with socio-political problems. According to our interviewees, when covering such events, writers were obliged to swap the word “political” for “social”, for example. They also remarked that editors had lists banning certain artists, any overtly political, religious or pressing social issues, and all mentions of sex and LGBTQ+. Consequently, since writers could never be sure which of their articles would make it past the censors, they went into self-censorship mode when writing about “undesirable” topics.

Official publications deploy two types of censorship: top-down (from the editors) and bottom-up (self-censorship). No independent media editors have ever imposed such restrictions, but almost all their writers have resorted to self-censorship, in the form of milder wording, intended to shield independent art professionals and institutions.

Starting from around 2015, independent writers began to actively appear in various foreign art media, publishing texts on both world and Belarusian art. This is an important trend to promote Belarusian independent art and bring it into the global art arena.

Information on the independent art world still needs to be compiled and archived, since official publications have ignored its activities, and it risks being erased from Belarusian art history. Several major online projects were set up to counteract this. The constantly updated online platform Kalektar,[6] for example, which features lists of Belarusian artists, curators and critics, plus glossaries, lectures, photographs of works, exhibition reports, and articles. It was founded by the Belarusian artists Sergey Kiryushenko and Sergey Shabokhin, with curator Aleksey Borisyonok: “We created the platform primarily due to our dissatisfaction with the state of Belarusian contemporary art, and its relative invisibility in the Eastern European and international context. We have currently amassed a wealth of material which will be used to create a public-access archive of Belarusian contemporary art. This is vital, not only to save another period of artistic development from being doomed to oblivion, but also as an example of resisting the excesses of state cultural policy”.[7] The Shklo platform, devoted to contemporary Belarusian photography and visual arts, was founded by Yuliya Volchek and Maksim Sarychev, but has been inactive since March 2021. Significantly, it was based on Facebook and Instagram, with posts in English, which helped the Belarusian alternative art scene break free and open up to the global context.

Research and archiving was also the goal of Antonina Stebur and Anna Samarskaya’s Historyja Belaruskaj Fatahrafii (2019), and Anna Karpenko and Sofiya Sadovskaya’s Biazmezhniki (2020) on inclusivity in Belarusian art. Although both books were based on years of research, they are now unfortunately publicly unavailable due to conflicts within the art scene, as well as the political factor.

Another important symptom of this period was that, since unofficial art critics and journalists had nowhere to present their in-depth critical texts, several of them launched their own art blogs on social media and YouTube.

Although the above initiatives were clearly vital, they were unable to sustain the same level of interest in contemporary art as in 2004–2015. Another key factor is that the alternative sector is poorly consolidated, hermetic, and lacks financial support from the state or business (owing to the absence of political and economic freedom in the country).

On the other hand, judging from past experience (especially “partisan” survival tactics designed to preserve the unofficial art community), this “pause” may also be a way out in this unpleasant situation. The fact that the independent sector is decentralised and fragmented is possibly safeguarding it from constant censorship, attacks, and the scrutiny of state institutions.

“You understand why…” – post-2020

The socio-political situation in Belarus following the crackdown on the 2020 protests threw the country and its cultural environment into gradual decline. Independent galleries, cultural hubs, and music venues have closed down, e.g., Ў Gallery, Kryly Khalopa, the Korpus centre, and the club Graffiti. The country is sliding back towards Soviet practices, with new ideological departments being set up in state institutions, and all cultural exhibitions, lectures, concerts, shows, etc. at all venues nationwide now subject to state monitoring.

Nowadays, the art scene has been “purged” of “undesirables”. Many artists, curators, critics, and art experts have been forced to emigrate for political or safety reasons. Their work abroad is often linked to the socio-political processes in Belarus and the war in Ukraine, but adapted to suit the local scene in their new host countries. However, their activity is largely unknown to wider audiences (in Belarus and abroad), due to the censorship and lack of independent art publications. Scanty media coverage of the Belarusian arts both inside and outside the country limits the picture of artists’ and curators’ activities, wherever they are based. This is detrimental to the alternative arts sector, which is physically scattered over a range of countries, and poorly interconnected.

Exhibitions are now held at official venues in Belarus, and sidestep any socially relevant issues. After the closure of several exhibitions in 2021–2022, the independent sector has reverted to operating in “apartment” conditions, like in Soviet times. For their own security, curators and artists now avoid making openly critical remarks, so censorship and self-censorship are increasingly applied in the cultural field.

Our interviewees commented that the present level of censorship in the media and culture in general is unprecedented in the past 30 years. Mastactva magazine, the last remaining arts publication in Belarus, has also been dismissing employees. The interviewees remarked that the “Aesopian language” typical of non-conformists during Soviet times is now more relevant than ever. The cliché “You understand why…” (as used by institution administrators when firing staff, removing works from exhibitions, or redacting/banning texts) has almost become a meme.

But the fact that Belarusian art “archives” exist (albeit with no dialogue or discussion element) means that independent art history is at least being preserved and added to, which is essential to prevent further information gaps. In turn, by continuing to write for foreign publications, journalists and critics can ensure that Belarusian independent contemporary art stays on the global agenda. One might say that the Belarusian alternative art scene of 2023 is in “preservation and standby mode”, underpinned by a dynamic tension between competing trends of activism and degradation. The low-profile yet regular activity currently taking place has every chance of accelerating in the future, as the art scene anticipates a qualitatively new outlet for its pent-up energy.

[1] V. Urodich, “Vokrug garmonii materialistichnogo i dukhovnogo”. Minsk: Mastactva Belarusi No.2, 1986, p.4.

[2] I. Koronevskaya, “Obrazno pro nadezhdu”. Minsk: Mastactva, No.8, 1995, p.13.

[3] Y. Voytovich, “Voprosy zvuchat kak nabat”. Minsk: Mastactva Belarusi, No.12, 1990, p.3.

[4] “Made in Belarus: konets ‘partizanskogo dvizheniya’”. pARTisan, journal of Belarusian contemporary art, https://partisanmag.by/?p=3292.

[5] O. Shparaga, “Demokraticheskiy potentsial kul’turnykh praktik v usloviyakh avtoritarizma: sluchay Belarusi”, Postsovetskaya publichnost’: Belarus’, Ukraina. Sbornik nauchnykh trudov. Vilnius: EHU, 2008, p.182.

[6] Kalektar, research platform for Belarusian contemporary art, https://kalektar.org/ru/events/

[7] “Zapustilsya portal o sovremennom belaruskom iskusstve Kalektar”. Kak tut zhit’, https://kaktutzhit.by/news/kalektar