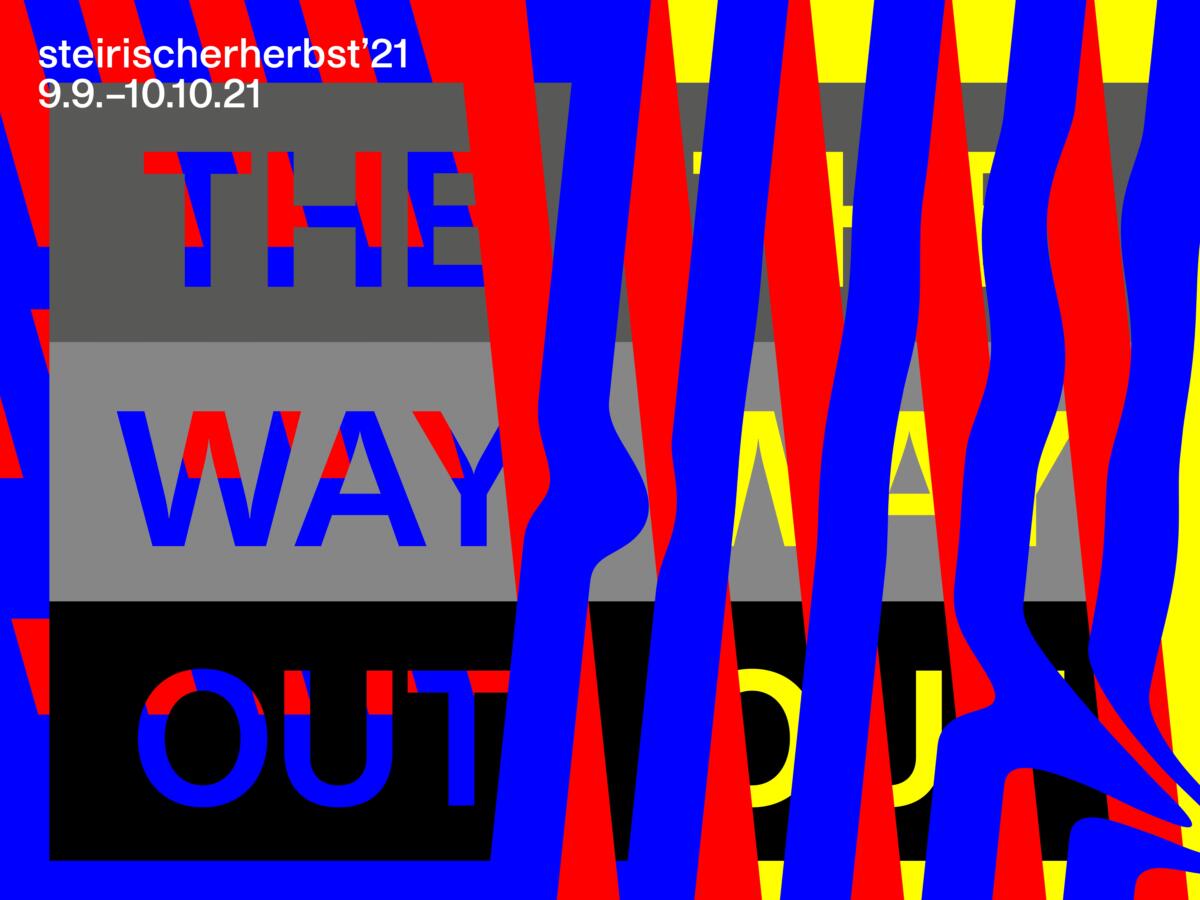

Based in Graz and borne of the need to counter nationalist cultural initiatives, steirischer herbst, now in its 54th year, has retained a motif of social and political hyper-locality and an historic European avant-garde approach to art and the everyday. Each annual edition is newly themed to reflect the tenor of the times, this year being The Way Out, an obvious metaphor for any number of crises for which we’ve found ourselves embedded in 2021, namely the hackneyed break from the sterility of the institution and white cube, favoring instead “aesthetically non-sterile environments, to risk the direct competition with street noise, visual pollution, and political dirt”[1], not to mention the pandemic-inspired need to limit indoor happenings. This years’ edition has included 33 artists/collectives, a parallel program, an education program, a literary festival (Out of Joint), a music festival (musikprotokoll) and STUBENrein, a literal festival within the festival.

During the conversation New Ecology of Exhibition-Making, held on the opening weekend of this month-long festival, some of the most in vogue questions about contemporary art were addressed. Moderator David Riff aptly reminding us early on of the exclusionary history of the European avant-garde and how access— to knowledge, to space, etc.— is a privilege that is the bedrock of Western contemporary art. And so within this context, Riff posed three core questions: what kind of new metabolic conception[2] is needed and how does an art institution today fit into the larger social metabolism, can we think beyond a neoliberal paradigm of care, and how can we address the rift between the digital and the real as we change our experience of engagement (travel restrictions, borders, etc.)? Over the course of two hours, panelists Sabina Sabolović, Anetta Rostkowska, and Matteo Lucchetti shared their collective experiences and proposed various possibilities: what if there was a proportionate reduction in the number of exhibitions staged at major institutions? What if it was half as many and they were twice as long, favoring the channelling of energy and resources into deeper, more nuanced conversations that could be broached by a broader audience, offering the potential for more meaningful and theoretically more diverse engagement? And, at that rate, what if artists weren’t being constantly asked to make new works (which is a criteria of participation in steirischer herbst), but if we found value in the re-contextualization of existing works, within new sites and communities and global (and local) conversations? What if curatorial, directorial, institutional appointments were five, ten, or fifteen years instead of one, two, or three? These propositions all feel exciting in this moment of global exhaustion and transformation from a pre-COVID world into whatever this current era is. But, will we actually build this new world or just wait it out a little longer until the booster vaccine is available and we can slink back into the routines that we’ve now become nostalgic for?

The evening before that roundtable, I stood in front of the installation by Marinelle Sanitore, Assembly, which sits just in front of Graz Hauptbahnhof. The lace-like, carnivale-esq light displays, or luminaire, read “I WANT A NAME LIKE FIRE LIKE REVOLUTION IO DI ME FARO UNA RIVOLUZIONE” and “AT THE HEART OF OUR EXPANSION IS THE CAPACITY TO BE VULNERABLE”. Set together facing one another I can’t help but feel like I’ve entered into a parallel universe where Jenny Holzer has been reborn as an electrified baroque scenographer. I welcome the flamboyance and bourgeois opulence as a casual observer, not as a transient or precarious body that might be the more expected audience passing through this arterial mouth of the city. Inadvertently amplifying this boundary are the metal barricades haphazardly creating a perimeter around the works as part of the COVID protocol the festival was charged with keeping. As I approached them, they transformed into a backdrop for a pair of security guards casually circling the sculptures. Wearing rather typical navy colored, double-stitched poly uniforms, complete with logos and holsters, all seemed normal until we hit the headgear, which had been grossly exaggerated, like a crossbreed between a traditional officer’s cap, a satellite, and a sombrero. It was impossible not to laugh. Once positioned between the Sanitore works, they pulled out twirling ribbons— the kind seen in competitive gymnastic routines— striped neon green and navy, echoing police barricade tape. As they casually walked amongst us, waving their ribbons, you couldn’t help but lose yourself in the absurdity. Another version of the performance continued in a nearby public park commonly utilized by migrant families; this time the guards were on horseback, engaged in a looped processional, which was guarded by an actual security team. Walking, stopping, turning, waiting; turning, walking, stopping, the cycle was performed for about half an hour.

Opening steirischer herbst ’21, Europaplatz, Graz, Marinella Senatore, Assembly (2021), installation, photo © Johanna Lamprecht

The play between reality and the absurd is an incredibly poignant, delicately balanced criticism set forth by Kasearu who presents a commentary on the increase in policing of public spaces in Austria, and the theater of it all. From here it is an easy leap to the seemingly global militarization of police, which is a physical, psychological, and social threat that Kasearu plays with gently and with point-blank accuracy. We laugh at the Disorder Patrol because the performers look ridiculous, and it feels good to be able to do this safely and with some distance. It is an apt reminder of the performative nature of wielding power over a people. Here the king is transformed into the jester using his own tools wielded by his own hand. This past year, many Americans and Poles (and Belarusians, and Chinese, and Burmese, and…) faced abuses of power with a particularly public unabashedness. I observed Kasearu’s performance and all others as a white American woman who has bore witness to and who has benefited from the racism, systemic oppression, and brutality experienced by and perpetrated unto non-white Americans. I also observed this performance as a woman who lives in Poland, who has witnessed first-hand the sanctioned violence that has been deployed in an effort to silence dissenters of this political regime.

Carl Pope Jr., The Bad Air Smelled of Roses, 2004-ongoing Exhibition view HALLE FÜR KUNST Steiermark Photo_ © kunst-dokumentation.com

Kevin Jerome Everson, Recover, 2021 Exhibition view HALLE FÜR KUNST Steiermark Film: Courtesy of the artist trilobite-arts DAC, Charlottesville; Picture Palace Pictures, NY Photo: © kunst-dokumentation.com

At Halle für Kunst Steiermark, which is included in the Parallel Program of steirischer herbst, Curator Cathrin Mayer continues this thread that is extended from Kasearu’s work through the presentation of two Black American artists, Kevin Jerome Everson and Doreen Garner, and The Study Room, a physical and digital discursive space featuring multiple artists which bridges the two solo exhibitions. The collective works of Everson were stunning in their pacing and composition; his interest in painting evident through the abstraction and textures of his landscapes and subjects, which range from gardens at night to city streets to family homes to solar eclipses. Everson’s work hinges on perspective; the protagonists are his family or close relations, in the film Cardinal, we see his niece craning her neck to gaze at birds through a set of binoculars. We are watching the watcher, who in fact, watches nothing because her magnifiers are props cast in bronze and painted black, rendered useless for their intended purpose. Cardinal was made before Christian Cooper became a household name through the actions of Amy Cooper (unrelated), who decided to wield her white power in Central Park in 2020. I leave this exhibition with questions of how politics of people and place move across oceans and into sites that have their own raw, contentious, and unresolved histories that still, today, continue to determine value, perspective, position, and opportunity. And how these stories and traumas are woven together and worn on and beneath the skin.

Doreen Garner, THE PALE ONE (detail), 2020 Silicone, urethane foam, pearls, Swarovski crystals, barbered wire, hair weave, fluorescent light, aluminum, steel, 153 x 91 x 113 cm Exhibition view HALLE FÜR Kunst Steiermark, Graz, 2021 Courtesy the artist and JTT, New York Photo: © kunst-dokumentation.com

As participating artist Mounira Al Solh pointed out, Graz as a city is a bit of a white cube already, which undoubtedly complicates attempts at subversion. In Western art history there is a historic discord between public space, the art that occupies it, the institutions and bodies that build it and pay for it and the people that exist around it, and despite the festival’s goal of confronting this, there were several quite straightforward perpetuations. One of the more glaring examples of this was the Simone Weil Memorial, a staged memorial site located on a sidewalk by Thomas Hirschhorn. The artist spent time observing how the site functioned as a thruway and was inspired to contrive a memorial to an obscure philosopher/activist that feels un-ironically theatrical; tokenizing gestures of real pain, suffering, love, aching, anger, and loss that provokes the construction of actual spontaneous memorials. In contrast, as part of the Parallel Program and located just up the street from Memorial is Annenstrasse 53, which provides one of the few moments of real critical tension in all of the festival-related encounters and experiences. As a space/collective/proposition, Annenstrasse 53 emerged in December 2020 and continues to consciously maintain its liminality both in its organizational structure and mode of operations. The space is defined as a learning space that asserts the idea of becoming a student – how to learn and how to be learned in all its uncertainty. By unravelling standardized and oppressive structures that emerged with colonialism, Eurocentrism and Americentrism, forced acculturation, fascism, and capitalism, ”Annenstrasse 53,” conceptualizes and practices exhibiting as a continuous, open-ended process, where cross-reading generates novel thoughts and debates, as something that is thought beyond temporal and spatial closure.[3] For steirischer herbst, they presented Films for a Free Palestine—Sequence III, a series of films and conversations selected by Daniella Shreir. They ask their audience to recall recent Palestine solidarity actions in Austria, and how the violence of expulsion and war acts can be reflected upon, locally.

Mounira Al Solh, Things My Neighbour Could Say as She’s Watching the Sunset (2021), poster in public space, Graz. Photo: Johanna Lamprecht

Referencing Bob Dylan’s 1967 All Along the Watchtower in her opening speech, four-time Director and Chief Curator Ekaterina Degot proclaims the joker and the thief to be inspirators of sorts, as the ones that can find their way out. In the roundtable Competing with Public Space, in reference to the ritualization of our everyday routines, the power of mystery and curiosity, of the unexpected, and the possibility that exists in moments of provocation became a point of focus. In the teaser for the operatic performance Conversations: I don’t know that word … yet by Dejan Kaludjerović in collaboration with Marija Balubdžić, Bojan Djordjev, and Tanja Šljivar, interviews conducted with children on the topics of social and geographic politics, economics, etc. are sampled, abstracted, remixed and performed by adults. At times funny and others heartbreaking, it was a sobering reminder of how early our conceptions begin to take hold and shape our vision and paths. But as well, it was also laden with the brightness, awkwardness, and the potential that exists when all possible paths still lie ahead for the choosing.

There is a sense of playful criticality that is cast over the net of steirischer herbst; a twisting and skewing and repositioning that separates the political gestures here from the meme-making and abject violence that also somehow qualifies as art in this moment, which is being championed by the fascist regimes that this festival was first designed to combat a semi-centennial ago. And after reading my love letter from Paul B. Preciado, I pause:

I do not love you because you are male or female, or because you are not. I do not love you because of the color of your skin. I do not love you because of the shape of your body or your ability to walk on two legs. I do not love you because you are healthy, or because you are a promoter of wealth. I do not love you even for your ideas. I address you as a living, mutant, irreducible entity. This is how I desire you: in mutation.[4]

Dejan Kaludjerović in collaboration with Marija Balubdžić, Bojan Djordjev, and Tanja Šljivar Conversations_ I don’t know that word … yet (2021), opera performance, photo_ Mathias Völzke

For some of us, this question of the way out is a thought experiment while for others it is life or death, without will or control. What do we take away from all of this in a moment when bodies are being pushed back and forth across borders, when some simply have no way out? How do we live responsibly, ethically, and with generosity of spirit? How do we make and experience art in this climate, when mutability is afforded to only those who have a way out? I have no idea. But it does make me wonder if the way out is in fact only another way back in.

[1] “The Way Out to Art? A Polemical Introduction” https://www.steirischerherbst.at/en/program/2346/the-way-out

[2] referencing John Bellamy Foster’s term ‘metabolic rift’ as a continuation of Marx’s work on the relations between humans and nature, and the divide that is exposed by capitalist production

[3] statement provided by Dr. Rose-Anne Gush of Annenstrasse 53

[4] Preciado, Paul B. “To All I Will Love”, 2021, steirischer herbst, Graz, Austria

Imprint

| Artist | Yael Bartana, Uriel Barthélémi, Sophie Bernado, Sophia Brous, Faye Driscoll, Samara Hersch, Lara Thoms, Žiga Divjak, G.R.A.M., Felix Hafner and ensemble, Thomas Hirschhorn, Hiwa K, Dejan Kaludjerović, Marija Balubdžić, Bojan Djordjev, Tanja Šljivar, Flo Kasearu, Paul B. Preciado, Die Rabtaldirndln, Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping, Peter Schloss with Grupa Ee, Tino Sehgal, Marinella Senatore, Hito Steyerl and Mark Waschke, Lars Cuzner, Stefanie Sargnagel, Pia Hierzegger, Nicholas Grafia & Mikołaj Sobczak, Heimo Halbrainer and Joachim Hainzl (CLIO), Nilbar Güreş, Hans Haacke, Horst Gerhard Haberl, Li Ran, Boris Mikhailov, Amanullah Mojadidi, Dana Sherwood, Mounira Al Solh, Piotr Szyhalski, Rosemarie Trockel |

| Exhibition | steirischer herbst 21' |

| Dates | 9.9.–10.10.21 |

| Curated by | Ekaterina Degot, Henriette Gallus, Christoph Platz, David Riff, Dominik Müller, Mirela Baciak, and steirischer herbst team |

| Website | www.steirischerherbst.at/en/ |

| Index | Kathryn Zazenski sterischer herbst |