This conversation was held on Zoom and has been edited for clarity.

Andreas Werner: Okay… Do you hear me?

Ewa Borysiewicz: Yes, I think it works… First of all: how are you?

I’m fine. Back from holiday, from Croatia.

Where did you go in Croatia?

Korčula, one of the islands in the South of the country. The last six months were fairly busy: I had a big exhibition at Kunsthalle Krems[1], then a solo show at the KRINZINGER[2], and now, the main STRABAG Artaward…[3] The pace was overwhelming. Don’t get me wrong: I was – and still am – very glad about all this, but I needed some rest. Korčula was a perfect place to relax, swim and reflect on what has actually happened this year. Thanks to this moment of pause I could appreciate all these events and do some reading.

What did you read? In one of the interviews, you mentioned an interest in science fiction.

True, I usually read science fiction literature, but now I’m back to Leb wohl, Berlin (Goodbye, Berlin, 1939) by Christopher Isherwood. It’s a German book about a period I am interested in – the 1920s in the German capital – and the main subject of the novel is the behavior of the people during that time. I’m fascinated by the architecture from that period, the one depicted in Metropolis and other expressionist movies. So, I was researching Berlin of this era and wanted to learn how people live in this particular architectural context.

What did you find out? What part of the reading was relevant to your research?

I focused on the relationship to a place, the context influencing one’s everyday life. I was curious to understand how this expressionist urban setting and the often-romanticized belle époque morphed into this disgusting nazism in the end. How very slowly, almost imperceptibly, it progressed. Step by step, always a little further into this horrifying direction. And for the people living there and then, it was not a sudden change, right? „Now we are this, and next – we are something else”. It was a gradual process. And for sure, some people realized the ominous nature of what’s happening in Berlin or in Germany. But I have the impression that most of the population was ignoring the reality surrounding them, as if daydreaming. And when they woke up, it was already too late. I was born in East Germany and grew up in the DDR, so my interest in these processes is self-evident.

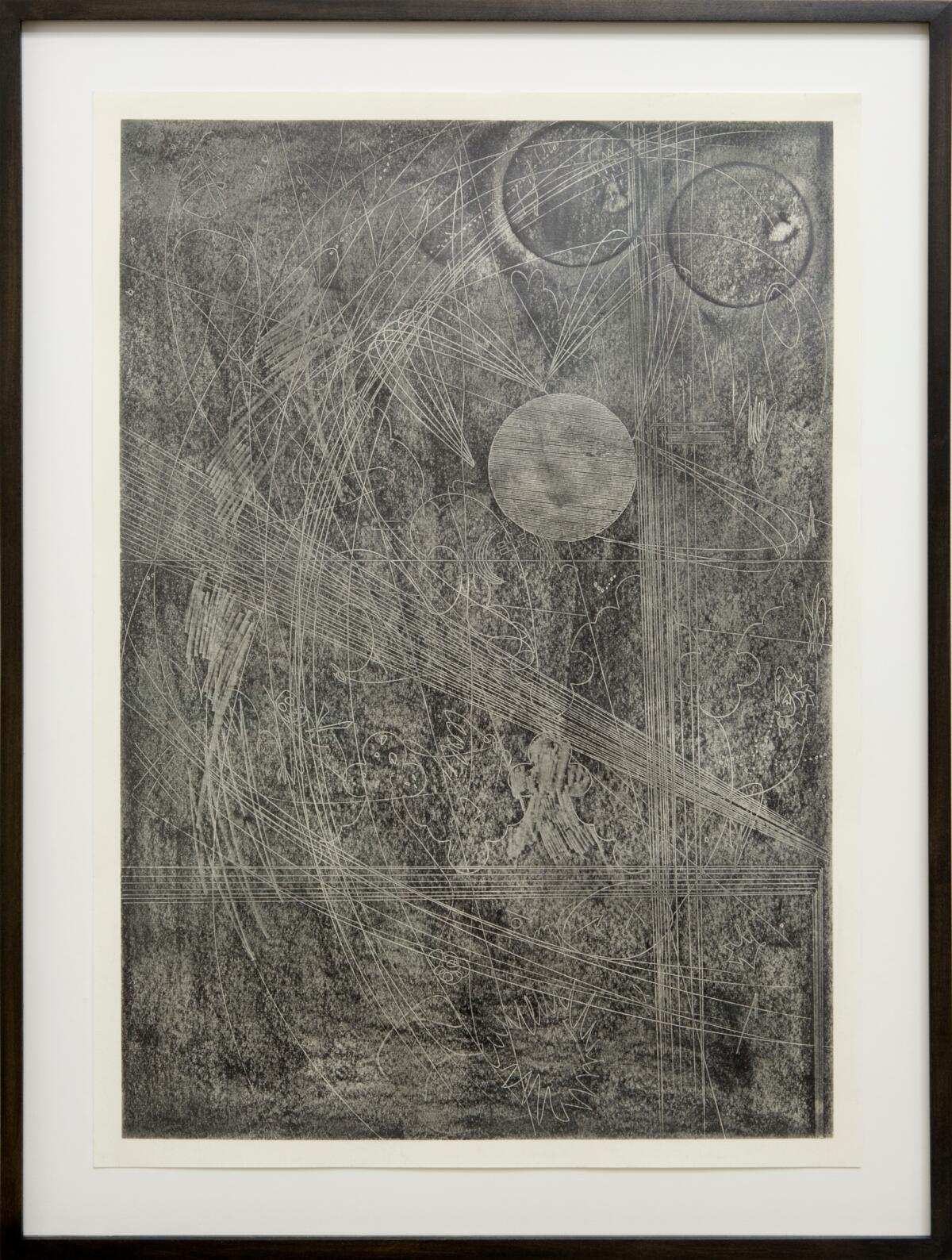

Your fascination with architecture is quite visible in your work, especially in the drawings done with a graphite pencil.

Yes, that’s true. I’m particularly keen to explore the ways in which architecture – the art of designing facades and solids – have an influence on people. What do these silent edifices communicate? All buildings convey a concrete meaning… When you walk around in a city you can sometimes sense what they want to tell you, giving you hints on the inner workings of a culture they are representing.

And when you draw your… I don’t know how to refer to them – perhaps „temples”, or “constructions” works well – do you imagine a function for them? Are they meant to be inhabited or are they more like monuments that are supposed to carry a certain message into the future, reproducing a fixed vision of a past?

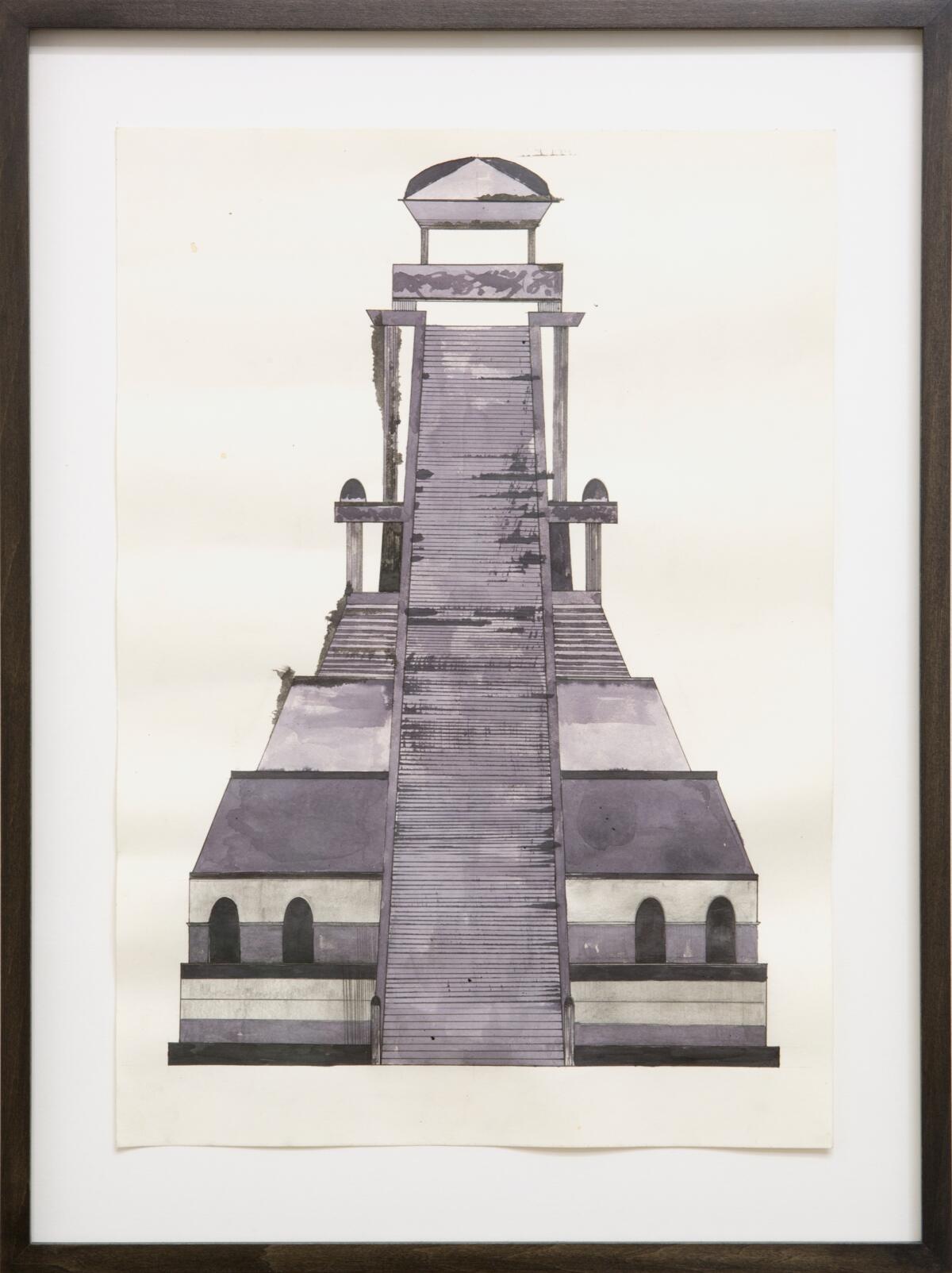

It’s a good question. At the very beginning they reminded me of robots or mausoleums. And the longer I worked on them, they became temples. You’ll notice that in the drawings, there are no human beings around, no witnesses, no users. You just see those relics, traces of a lost culture. And you can’t really put a time stamp on them, for all I know they can be a year or a thousand years old, like panoramas of ruins of a past or a future civilization.

I find the combination of anthropomorphic and architectural characteristics of the structures you depict very curious. Could you tell me something more about it?

Yes, absolutely, both robots and buildings come from a human perspective, they have a human view of the world in their roots. I had a moment of enthusiasm towards the early stages of space travel, my drawings from back then resembled rockets and spaceships. I researched the story of Wernher von Braun, the German aerospace engineer who fled to the U.S. after the Second World War. His new supervisors – although they knew about his personal involvement in the Nazi Party and his rocket discoveries used by the Nazi German military – allowed him and encouraged him to work for the American army. These layers of “knowing but not asking”, the overlapping of convenient silences and “practical” ignorance, resulted in a certain aesthetic which was then transferred from one civilization to another. This problematic layer allows for societies to work. So, my “rockets” acquired anthropomorphic characteristics, perhaps because of a connection between individual and collective history.

This reminds me of my visit to an archeological site. Fritz Krinzinger, the husband of my gallerist, was one of the people responsible for the digs in Ephesos. He showed me around, and thanks to him, I learned a lot about the ancient Greek and Roman societies, how they built their societal and urban structures, and had a chance to witness what has now remained of those once impressive complexes. I think I managed to incorporate this experience into my work. The constructions I depict began to combine some aspects of places of worship, spacecrafts, and human-like figures. It’s an uncanny mix. I don’t like to specify their function; I enjoy the uncertainty. You, the viewer, can see quite clearly that a drawing depicts an edifice of sorts – but you can’t say what it is exactly.

Right. Most of your work is black and white, which adds up to the mystery behind the structures you depict. Also, most of your work is done in graphite, a material that’s a very close cousin of coal. Since you mentioned growing up in a city covered in carbon dust, I was curious if there is a “Freudian” reason for this choice of medium?

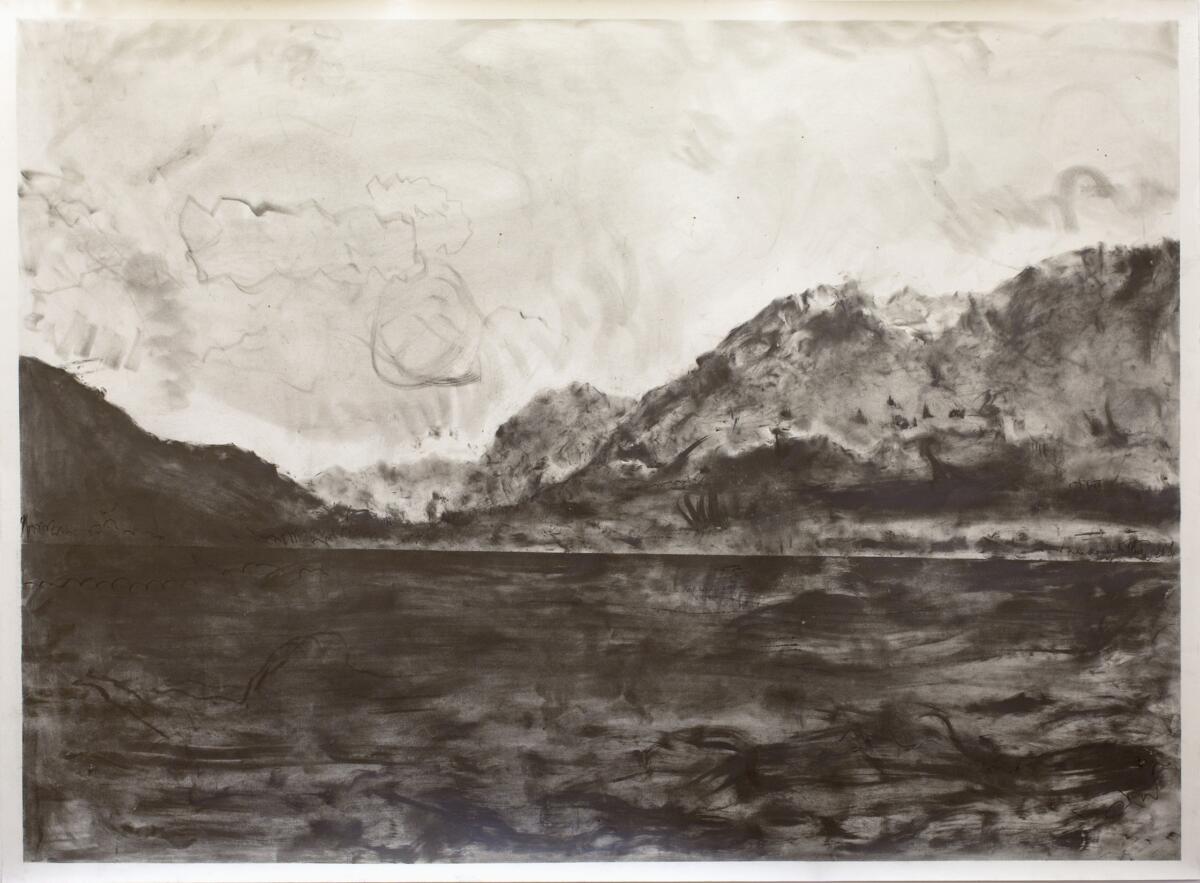

I was thinking about this too. I was born in Merseburg an der Saale, close to Leipzig. It was one of these industrial cities of Eastern Germany, manufacturing petrochemicals. I also remember the coal mines in the region and that the Saale, the river, was black because of the dirt. At that time, nobody thought of the damage done to the environment, the factory managers pumped out the waste from the petrochemical plants directly into the water. The river was just black, practically dead. Everything was covered in ash. When I think of it now, it’s a terrifying memory, but as a child I thought it was somehow painterly, picturesque even. A melancholic grey landscape symbolized the coexistence of beauty and danger, the destruction accompanying man’s inventiveness.

The „romantic beauty of ruins” and all that!

Haha, yeah. I consider this extensive German painterly tradition of Romanticism and landscape painting – like in the works by Caspar David Friedrich – as one of my main sources of inspiration. And his landscapes are vast, wide, and there are usually no human figures around, just this awesome view. During my studies I was very interested in the Romanticism period in the arts since it happened during the peak of the industrial revolution in both Germany and Great Britain. I imagine that back then everything was full of dirt, coal, noise, full of this blackness. And Romanticism was like a reverse side of this process and painters set on depicting these sublime sceneries that did not really have an equivalent in reality. It was just imagination. And this discrepancy, the contrast of what one wants to see and live in, and the conditions in which one actually lived, interested me a lot. One can say that my enthusiasm for spaceships has its origin in Romantic landscape painting.

Right. Romantic landscapes also meant to convey or illustrate certain sentiments.

Absolutely. In the end one can call it escapism. We don’t want to see what reality is, so we make up our own, better world.

I’m wondering whether it also connects to a sense of feeling like a tiny, insignificant part of the environment. Almost like a mistake, an aberration.

Perhaps. Like I said, Romantic landscape painting was concurrent to the time of the first industrial revolution. This passage from the Bible: „Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the Earth, and subdue it”, make the world your own, bend it to your rules, this was the prevalent idea at that time. The Earth was perceived as an instrument, not as an ecosystem.

In contrast, some of today’s science fiction literature advocates for considering our planet as an ecosystem. I was recently re-reading Stanisław Lem’s Solaris. He was way ahead of his time – he wrote this book 60 years ago – the main protagonist of the book is the titular planet, a mysterious whole, a living, gigantic and empathic organism, interacting with the human crew of a space research station.

But coming back to the XIXth century: at the same time, the artists depicted nature as a great, incomprehensible phenomenon, cosmos, God, the higher power, whatever you call it. It might be interpreted as a reaction to this „everything goes as long as it’s progress” mentality of the industrial revolution.

This might relate to this recto/verso interpretation: I was very curious about the titles you use. Most of them are very poetic – like a starlit or moonlit dome reflects (2019), the glittering reaches of the flooded lake (2019), or I feel like my soul has turned into steel (2018) – their meaning is fluid, ungraspable, contrasting with the solidity of the edifices they accompany. How do you come up with the titles and what kind of meaning do they have to you?

I don’t want to use titles that would hint at the meaning of the work too strongly. In the end, you as a viewer should discover it for yourself, and ask yourself what you feel in relation to the work, what associations do you have. During a residency in Ireland, I read a lot of British and Irish poetry. One library threw away a bunch of books by Wilde, Heaney etc. and I was lucky enough to have the possibility to buy them all and send them to Vienna, where I now live. They are now stored in my studio. The procedure of picking the titles is intuitive – I read the poems, observe my drawings, and sometimes I find a line that fits perfectly.

all I believe that happened there was vision (2019) illustrates that well. The phrase suggests a scene happening in a dream, a nightmare perhaps, and a menace hidden behind a black parabolic-shaped door positioned in the center of the drawing. It somehow reminds me of the Alien film series and the designs by H.G. Geiger, who also mixed the organic with inorganic in his work.

I love old sci-fi movies. I started with Fritz Lang’s Metropolis – the mother of all science fiction – and then came Solaris, Blade Runner, Alien… When you watch Blade Runner, you notice that the dystopian 2019 Los Angeles, is a modern equivalent of the ancient city of Babylon – human hubris and fantasies about omnipotence prevail. And the architecture itself resembles the one constructed by ancient societies – it seems that the distant future and the ancient past collide and merge. Also, when researching Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Inca or Mayan constructions, you suddenly realize that they all look similar, they are governed by the same basic rules, the same archetype.

All architecture was made by humans, we’re the same species, we must have something in common!

Sure, human beings have a shared basic idea of what a building should be and the purpose it should serve. Castles, temples, halls, whatever. There is a recurring idea, an idea that every society has developed without communicating with one another.

So, what you’re doing is a collage of these architectural archetypes.

Yes, mixed with strange science fiction elements. The various visions of the future – the optimistic one from the 50s, the apocalyptical one from the 80s and on – this is also what interests me. As you know, science fiction was a very popular genre in the Soviet Union, also because it was a way to criticize the present without naming the culprits explicitly. Describing the structure of a society in a galaxy far, far away, you could articulate very concrete criticism about the issues closest to you.

I agree. This makes me wonder if this remark can be applied to your work as well? Is there something you would like to criticize, condemn, or point out?

I was born in East Germany and then I grew up in Austria, Vienna (my mother is from Germany, my father is Austrian). Until I was five, I lived „behind the Iron Curtain” so to say. And then in West Berlin or in Vienna, coming from the East as a kid, I was amazed by the amounts of goods in supermarkets, the lights, the all-present advertisements, the abundance. It was like a different world. And only from a time distance can I see the problematic foundations of the current neoliberal system. The 90s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the “American way of living triumphed”, were an extreme version of an “anything goes, everything is possible/ available” attitude. A party like there’s no tomorrow, or no responsibility towards tomorrow. The problems we’re facing today, their roots can be traced to that period. And now the youngest generation is wondering if they can still live on this planet. In German you say that „we are racing toward the abyss”.

And we’re going full speed.

Yeah, but is there a solution? There does not seem to be an answer to this question, at least for now. Science fiction movies from the 70s, like Star Trek or Star Wars have this optimism in common, a belief that the future will be a better place. A romantic idea that we will all enjoy a peaceful life in extraterrestrial colonies. A beautiful fantasy. When you look at contemporary science fiction, they are mostly dystopian, their starting point is a conviction that “it’s the end, it’s over now”. The view of the future in science fiction changes completely within these 30 – 40 years. My explanation for this was that it connects to the end of the Cold War, the two sides of the curtain merging into one and the careless euphoria that followed – this big Wall Street party included – and now we must face the consequences.

So, that’s the critical aspect in my work. But I also need to stress that I am not an educator. This is how I understand my drawings, but the viewers should find their own interpretations and reach individual conclusions.

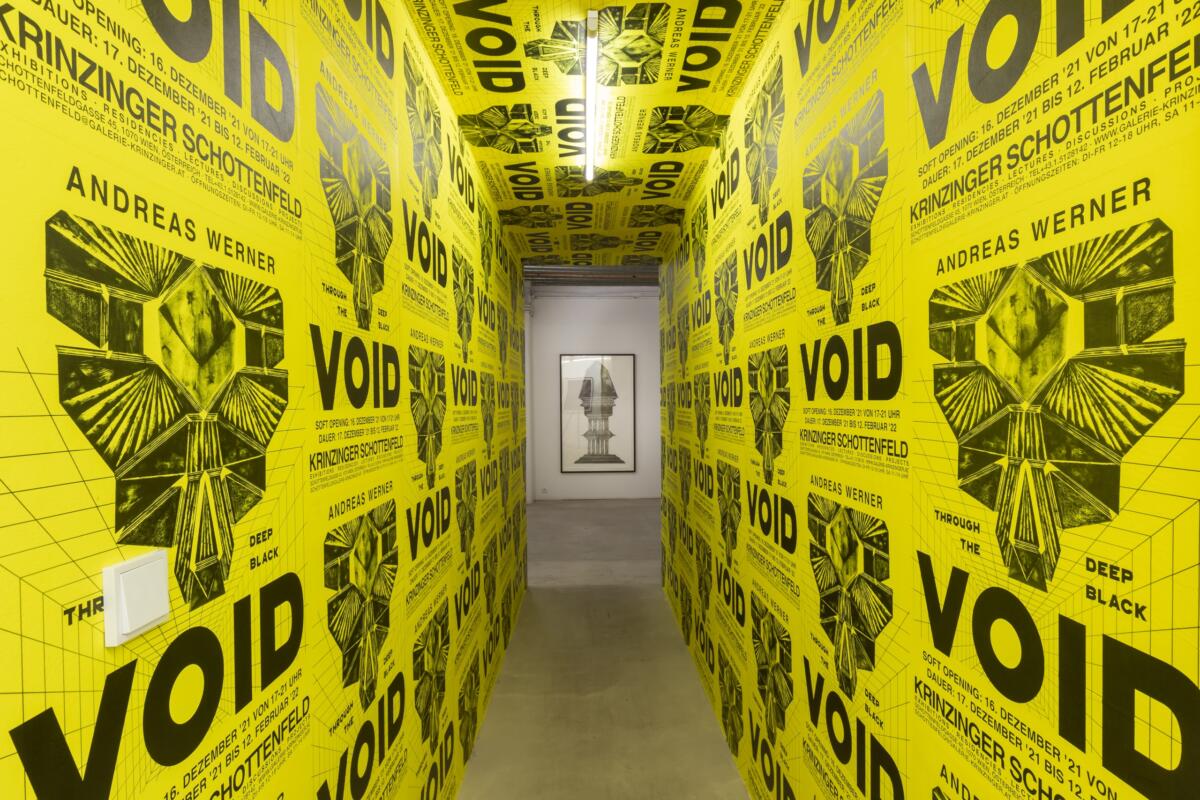

One of your recent shows, THROUGH THE DEEP BLACK VOID in KRINZINGER SCHOTTENFELD had a very 90s ambiance!

Yes. It was built upon a contrast between this sacrosanct white cube feeling and the unaccountability and carelessness of a 90s rave party. The posters announcing the show at entrance, covering the gallery walls quite densely and their color – acidic yellow plus fluorescent green – gave an overall impression of uneasiness and disorientation.

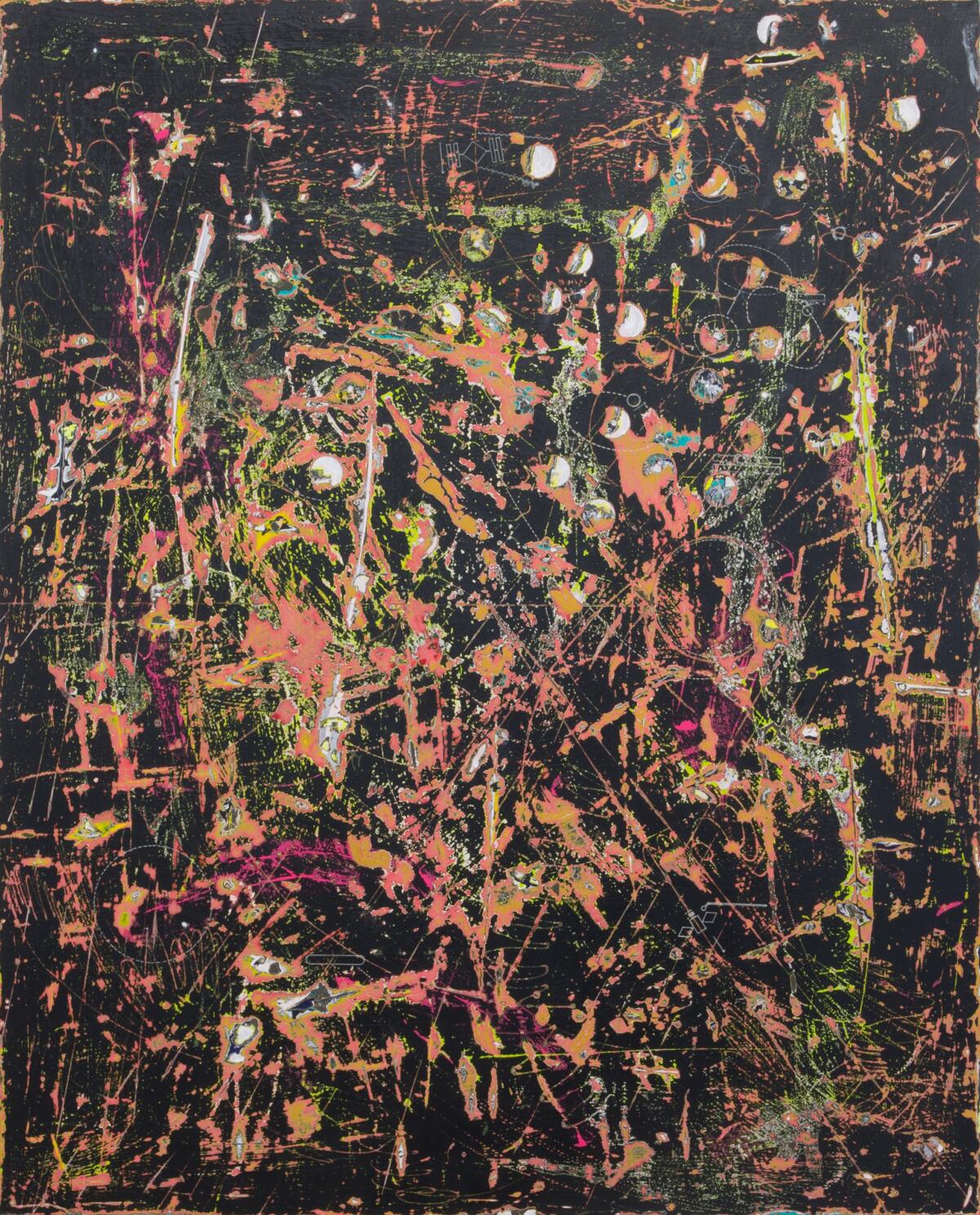

I wanted to ask you about one painting series in this exhibition, the Raumroute (2019). Could you explain the creative process behind them?

This might relate to the “layering” we were talking about. I started imposing one drawing onto another, covering one wooden surface with 30, sometimes 40 layers. And then I applied one wood printing technique and scraped pieces of the coating from the panel. As a result, little lines and spots of color started appearing, creating a final, abstract composition.

It’s a very “archeological” method.

There definitely is a connection. Archaeology is captivating, poetic even – people working on archeological sites remove one tiny layer of dust, a centimeter of dirt, which sometimes equates to 500 years of human history. It’s like digging up time. You move back, layer by layer, deeper into the history of mankind.

It must be fascinating to observe how the surface of these Raumroute works changes.

And it develops its own beauty in the end. I usually have an idea of what I want to do, but I can’t control the process fully, this technique is almost impossible to master. So the works have their own logic and perhaps, agency.

There’s also another emergent trend in science fiction, the one based on quantum physics and the multiverse theory. Reminds me of the escapism we discussed a couple of minutes ago.

I agree. Some things may be improved or fixed, but only in those alternate universes. The one we live in is broken beyond repair. The optimism, the enthusiasm, the carelessness is gone. I am not sure that now, a utopia – like the one represented by the Enterprise spaceship, traveling through the cosmos in search of new worlds – could be conceived and portrayed in a film or book. That’s over. Nobody would produce something like this today.

Maybe the present is so incomprehensible, so hard to grasp, that you can’t think about the future anymore. Discovering new things about the here and now and understanding the mechanisms happening right now might be the new science fiction in a way.

Right, the present feels surreal enough. Half a year ago, nobody would think a war in Europe would occur again. I am well aware of what’s happening, I know the death, the blood, the suffering are real, but I cannot comprehend it nevertheless.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

The STRABAG Artaward International is one of the most highly endowed private art prizes for painting and drawing in Austria. In 2022, an open call for the STRABAG Artaward International was announced in Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Austria. The prizes were awarded by Thomas Birtel, CEO STRABAG SE, on 9 June 2022 in Vienna.

The exhibition, with the works of Andreas Werner, the main prize winner, and the four recognition award winners could be seen at the STRABAG Artlounge from 10.6.-19.8.2022. A catalog will be published to accompany the exhibition. In September 2022, all award-winning artists will have a solo exhibition at the STRABAG Artlounge gallery space in Vienna.

In 2023, in a gesture of solidarity, the STRABAG Artaward International organizers will accept applications from Ukrainian artists in addition to those from Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Austria.

[1] Andreas Werner, Kunsthalle Krems 20. 11. 2021 – 03. 04. 2022, https://www.kunsthalle.at/en/exhibitions/25-andreas-werner, last accessed: 15.08.2022.

[2]THROUGH THE DEEP BLACK VOID, KRINZINGER SCHOTTENFELD, Vienna, 16.12.2021 – 12.03.2022, https://www.galerie-krinzinger.at/exhibitions/41055/through-the-deep-black-void/about/, last accessed: 15.08.2022.

[3]https://www.strabag-kunstforum.at/assets/Uploads/Webansicht-Artaward-2022-Katalog.pdf, last accessed: 15.08.2022.

Imprint

| Artist | Andreas Werner |

| Index | Andreas Werner Ewa Borysiewicz STRABAG Artaward International |