‘Speak in Order That I May See You Or Whistle And I‘ll Come To You’ at Christine König Galerie

In the musical creative process, the text of a poem provides, so to speak, a stimulus to awaken emotions or moods that had been there before, waiting for the release of expression. The texts have to fulfill certain musical requirements, but, more important, they must be able to stimulate, but are unable to fully express those emotions. The text has, as some composers say, to be spacious or “roomy,” not satiated with music. If it is not capacious in that sense, the composer has no possibility of expressing and expanding himself. Richard Strauss occasionally remarked that some of Goethe’s poems are so “charged with expression” that the composer has “nothing more to say to it”.

A Plea

On things that are not visible and not audible

The plea expressed in the title sets in motion a paradoxical mechanism that claims to be able to uncover the visible through the sonorous. As if the mute visage is not enough to truly see; to see beyond the apparition into the things for themselves – as they are when no one is looking. It is no wonder that the plea came from a psychoanalyst. It has a characteristic structure that while seeming to be a simple statement, upon further inspection reveals more possibilities of uncovering what is hidden. Theodor Reik used the sentence in a book that largely addresses the meaning hidden behind melodies that are obsessively occupying the thoughts and are forcing the obsessed to conform to the rhythm and repeat, either by singing, humming or otherwise play backing the piece. Today we know them as so-called ear worms – a notion that while Reik was writing his contribution to psychopathology of music in 1950s, was still not invented.

The title of this exhibition is taken from an essay by Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe on Reiks theory of subject: “But it is perfectly clear: while listening is privileged to the extent that it is necessary to consider it as more (or less) than a metaphor for analytic comprehension, it is nonetheless the case that, speech being finally mimic in nature and referring back to a more primitive gesture, listening is quite simply seeing. “Speak a little so that I can see you.”” All areas are being mixed in a constant movement that is referred to as catacoustics – the study of reflections of sound (the specular enters the picture for a reason). It can be perceived as a spatial relation that by the reflections of voices locates a certain relation in flux – an exhibition of voices, images and objects.

Lacoue-Labarthe ends his essay abruptly with a poem by Wallace Stevens that might become a motto signifying some of the qualities this exhibition wants to achieve:

The self is a cloister full of remembered sounds

And of sounds so far forgotten, like her voice,

That they return unrecognized. The self

Detects the sound of a voice that doubles its own,

In the images of desire, the forms that speak,

The ideas that come to it with a sense of speech.

The old men, the philosophers, are haunted by that

Maternal voice, the explanation at night.

They are more than parts of the universal machine.

Their need in solitude: that is the need,

The desire, for the fiery lullaby.

The Melody

On the musical structure of subjects

Reik’s ear was open not only to the meaning of speech but also to the details revealed by the melodies, rhythms, dynamics and tempos of utterances. This organ was practiced and turned into an interpretation machine while performing an act of auto-analysis. In 1925 Karl Abraham –an analyst whose influence on our protagonist was along with Freud the strongest – passed away and Reik was asked to prepare a speech for his funeral. Almost immediately after these two messages arrived his thought started to be disrupted by a recurring passage of the last part of Scherzo – the fifth movement of Mahler’s 2nd Symphony – Aufersteh’n. The text, based on a poem by Friedrich Klopstock, deals with resurrection. It took Reik almost 25 years to fully realise why he kept singing these words: “Rise again, yes, rise again, Will you My dust, After a brief rest!”. The simplest solution would be that the death of a friend and teacher awakened his belief in eternal life. That was not the case. In fact Reik needed to dig deeply into the story of Mahler who came up with the idea of the final movement while being present at the memorial of von Bülow – a patron who saw the young composer as a talented conductor but hated his music. Aufersteh’n was then a moment of mourning but also of a personal triumph. Mahler the composer was rising to eternal fame while his elder friend and teacher was being buried. The relation based on a quartet composed of von Bülow – Mahler – Abraham – Reik enabled the latter to seize and see clearly the mixture of grief and bliss that was triggered by the news of death. This compound remained unspoken – voiced only in memories of music and abstract text from the previous century until the whole relation was reconstructed. Music is at the foundation of the autobiographical impulse and its persistence allows oneself to write the self in the face of death and agony. The same spark of knowledge by learning to listen can be traced here: “So many things happen by bringing to light what has long been hidden. Lilting betwixt and between. Between what? Oh everything. Take your microphone. Cross your voice with the ocean.”

The Heroine and the Heroines

On things that are solitary while surrounded by other things

Yet another scene. A stage. Ophelia and the Words by Gerhard Rühm is a special play. One that is produced by reduction. All the other actors had left and Ophelia found herself in an impossible situation – she speaks in front of emptiness. The second layer is being created by the words (nouns and verbs) that are being isolated from her utterances and are being delivered in reversed order so that “Doubt” from her first line “Do you doubt that?” is being presented at the very end. The sonic stage is filled with objects and actions she brings to being by speaking. Rühm presents this as an act inspired by the stage design fashion of the day when the play was written about which Jean Paris wrote: “a tree what a forest, a big stone a rock face, and to capture the imagination, a note showed the place of the action.” In the film version of the piece they are brought as props being delivered either as words or as images. As the death of Ophelia is only reported by other people in the play, her demise is completely left out of Rühm’s staging.

Ophelia lives for eternity among words, sounds and images. American poet Susan Howe touched upon something similar when reflecting on her own practice and observed: “If you are a woman, archives hold perpetual ironies. Because the gaps and silences are where you find yourself.”

Another playwright who sought at first to reduce the text of Hamlet ended with a short but original play based loosely on the original drama. The part of Ophelia in Hamletmachine by Heiner Müller bears curious similarities. The heroine speaks: “Yesterday I stopped killing myself. I am alone with my breasts my thighs my lap. I rip apart the instruments of my imprisonment the Stool the Table the Bed. I destroy the battlefield that was my Home. […] With my bleeding hands I tear the photographs of the men who I loved and who used me on the Bed on the Table on the Chair on the Floor.” (the heroine appears also in the part entitled Scherzo, which resonates in an uncanny way with the finale of Mahler’s composition). Ophelia is surrounded not by people but instead by objects that she chooses to enlist. Moreover a certain sense of eternity is introduced by the recurrence of suicidal acts. The Loop, one of the objects that Atkinson speaks for can add: “Circles, echoes and clockwise revolutions, you will come back to where you belong.”

This repetitiveness as an element of social reproduction of models is present in a rendition of Ophelia in Zorka Wollny’s performance Ophelias. The artist gathered and choreographed a number of actresses who played the character from Hamlet in Poland. Different attitudes and spirits were manifested presenting together a resource on the history of interpretations of women’s madness. The work is treated by Wollny as a ‘theatre ready-made’ – a structure that was already around, that she pulled together to present the whole range and diversity as well as reproducibility by repetition of social roles.

The stage and props

Things that are half-way in one area while the other end is somewhere completely different

The exhibition comes to the stage which was cleared of everything except for the voice of the heroine. Away went the stage design and all the written words. We are left with the weakest element that one can hang onto – the ever-changing voice. The call was answered by two other voices: Susan Howe and Félicia Atkinson. All women have speech peculiarities: Atkinson whispers, Rühm’s Ophelia is an automatophone that delivers the part in an impassive voice and Howe is uttering parts of words on the verge of stuttering. The three radio pieces rebuild space. In Rühm’s Ophelia the noises and environmental sounds are recreating the long-gone stage design and props. In the piece by David Grubbs and Susan Howe we can hear birds and sounds recorded at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum where parts of Howes poems were written. Atkinson builds space on bass and distortions.

The three voices tell fragmented stories that prevent one form filling the gaps. “A story told is not a story read. It supposes a community. Orality, or more precisely, oral transmission, reaffirms listening as relational process. The narrative function mobilised by it is ultimately nothing but the fulfillment of the relational modality of listening. […] Listening projects and assembles phantasms and imaginary worlds that are established far away, only to be actualised in the intimate confines of the auditor.” This is another plea – one that is directed to the listener to recreate relations. After all the rests and gaps in the text form room for music. The text should be “able to stimulate, but are unable to fully express those emotions.” Susan Howe could add: “Somewhere I read that relations between sounds and objects, feelings and thoughts, develop by association; language attaches to and envelopes its referent without destroying or changing it – the way a cobweb catches a fly.” By imagining a cobweb outstretched in the room we could almost see how sonic waves are setting up a momentary networks of fragile connections. Catacoustics is a metaphor how voices reflect in the works on paper gathered in the room even if Atkinson claims that: “The stage is not a mirror, not a crib, not a graveyard, not a battle field, because there is no stage.” Rühm’s photomontages are pointing directly at the basic methodology: a montage of previously distilled parts. The drawings of Atkinson are partly collages, partly poems, that remain in a fragile balance not descending into any slot. Howe’s collage poems are the reworking of other writers fine pieces of works. She describes them as knots (we are again not so far away from catacoustics): “Quotations are skeins or collected knots. “KNOT, (n, not …) The complication of threads made by knitting; a tie, union of cords by interweaving; as a knot difficult to be untied.” Quotations are lines or passages taken at hazard from piled up cultural treasures. A quotation, cut, or closely teased out as if with a needle, can interrupt the continuous flow of a poem, a tapestry, a picture, an essay; or a piece of writing like this one. “STITCH, n. A single pass of a needle in sewing.”

The Performance

On the actions we only glimpse through images and words and sounds

All the pieces on paper can be seen as performance instructions, or quite simply notations. Structures that want to become other structures. Atkinson creates the drawings as a side effect of musical composition. She is not only channeling the words by male authors, but is opening herself to become a mouthpiece for the non-human: the sweater, the dice, the abstraction. She is a medium that gives voices to those that are voiceless. A piece of wood reflects on that: “I am a piece of wood. I lay in the ground and I don’t speak for myself, meaning, someone is speaking for me.” Another of these entities – the paper – describes how this process affects it: “Don’t burn me. Recycle? Anyway I feel the drawing and the handwriting on me, like I was carrying the weight of a strange whisper.” Her voice is usually whispering for a reason: “Whispering is a way to get inside your ear. It’s a feminist approach also to me. Whispering is a way to get inside, to take territory. To melt the inside with outside. It’s also a bit queer. It’s folding poles, making things less binary. It’s making knots and loops, like a snake, a silk scarf, or a river.

I whisper because I like to be close to the recording device I am using, usually my telephone. I whisper also because most of the time I record in my bedroom and I don’t want anyone to hear what I am doing.” The whisper offers another kind of intimacy. The voice sounds as if there is just one recipient and you are not sure if you are the one or you are just interrupting a strange ceremony. Whisper finally allows the things to materialise, but only partly as if a certain secret or timidity prohibits them from fully forming.

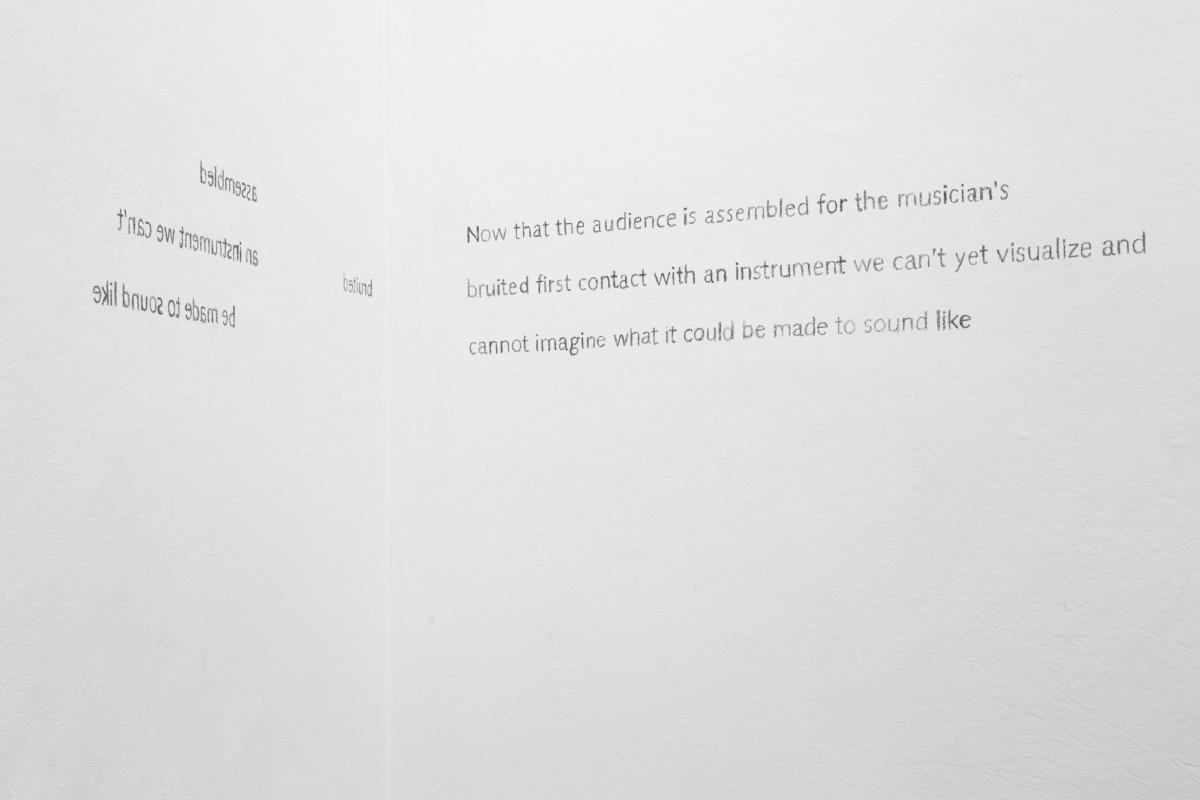

David Grubbs, Howe’s partner in musical explorations is also an author of a lengthy meditation on musical performance. His poem entitled Now that the audience is assembled is a surreal and funny but also intense restaging of a lot of affects that occupy the person presenting herself and her work to a gathering of people. The resonances between what we are dealing with here are clear: the performer is a woman, that reads a composition written by a man in order to present the best rendition of a really complicated piece whose first instruction is to: “Compose a gesture that can be repeated.” The stage filled with a heap of rubble from which the performer is extracting her instrument is a scene of a number of actions by different characters (composer and page turner included) that are exaggerating every choice that the performer makes into cosmic proportions. Partly science fiction, partly accurate to the facts and affects, this narrative becomes a detailed testimony of sweet and terrifying nature of exposing oneself before audience. Moreover, the medium Grubbs is using is quite simply an ekphrasis – a description of visual event in literature. Parts of the narrative gain a second moment in the exhibition as they are brought back as drawings on the walls. They are:

Now that the audience is assembled for the musician’s

bruited first contact with an instrument we can’t yet visualise and

cannot imagine what it could be made to sound like

and

With breath held, I could have you expelled.

En-

counterpoint

of two opposing breaths. In the absence of feedback, however quiet, the audience resumes the exercise of breathing as one. One breath for now after the last and after the next. A hush, a wave, a sequence, a series, and

o

no longer listening within a sound. Within an interior now voided. Within an interior now forgotten. The wave crashed. The curl ripped. The rip had it, had had having had it. With breath following breath, with breath hocketing breath, audience and musician encounter one another as airily unvoiced instruments.

Waves of organised breaths are forming the frame for performance. Moreover, the frame is filled with mirror as the wall drawings are composed of two parts mirroring each other’s yet they do not form perfect reversed copies – there are other fragments of the same sentences on both sides. This plays with the catacoustics metaphor as the voice reaches different spatial points at different pace and moment. Hence the mapped environment has diverse densities. Again on another level the words of Howe are helpful to comprehend the structure: “Listening now, it’s as if a gate opens through mirror-uttering to an unknowable imagining self in heartbeat range. When we listen to music we are also listening to pauses called “rests”. “Rests” could be wishes that haven’t yet betrayed themselves and can only be transferred evocatively.”

The Return to Things and Words

On the materialised and vocalised relations

The last room leaves space for words and objects as final products of the process. Toni Schmale calls her sculptures following Donald Winnicott transitory objects. She defines them as: “Transitory objects are the first possessions outside of oneself – they are at the same time “me and not-me”, a connection between inner and outer realities. It is the object loaded with context and meaning, which is used as a tool that makes the separation from “the good-enough mother” possible. I understand the “mother” to be the first connection to the outside, separate from gender and ability to reproduce. This being at a point in time when there is no distinction between the inside and outside – everything is me.” They are machines devoid of manuals, they speak of abstracted sadism and conforming body to the social constructions. The violence is present but not voiced or exercised. They are clean and unused. The process of producing them is brought back in the sketches. Schmale selects among the drawings to press some of them in concrete, thus fulfilling the circle: imagining a mechanism and its potential influence on body, executing the outcome and then returning to the creative process and closing it with a concrete plate. A strange kind of notation. One that leaves nothing to perform in accordance with the score. They are more describing relations than creating them, nevertheless just like words, they are indispensable for creating them. They serve as words described by Howe: “Words are visually concrete and tangibly audible. A poet surrenders with discipline to the sense of sound, sight, ideas, and rhythm in conjunction. Single words and sentence clusters directly affect involuntary memory. Involuntary memory is lucid, pre-verbal, soothing.”

Also Atkinson needed to come beck to basic relations through the act of voicing objects. She confessed: “I wanted to come back to Le Parti Pris des Choses. I needed this attention to objects. In this digital, image-oriented world, whats the experience of describing a thing in depth, with only words, without image? I tried to consider this material as dark matter I would soak and fall into, a slow typhoon, using on one hand, Alice in Wonderland’s method, in which she swirls in the underground and on the other hand, the avant-garde collage method, in which I would deconstruct the text and move words like pawns in a chess game.” Howe could add: “Each collected object or manuscript is a pre-articulate empty theatre where a thought may surprise itself at the instant of seeing. Where a thought may hear itself see.”

The Imp

On the labour of stitching together

Ophelia made to utter the words written by a male author and to stage madness for his pleasure has an interesting double in the world of Susan Howe’s poetry: Tom Tit Tot. The imp that promised to do ordered by the king weaving work for a girl. In return she would be carried away by him if she cannot guess his name by the end of the month. By chance the imp is heard saying: „Nimmy nimmy not. My name’s Tom Tit Tot.” The girl uses the name and the imp disappears having done his job. The work has been done by others. What is important it to piece them together in a new way. To stitch them together so that they begin to mean anew, just like another object voiced by Atkinson: “I mean something. Or maybe I don’t mean anything. I am the resurrection of the SPACE and I am the resurrection of TIME.” But the objects do mean, they can be reread through the recomposition. Howe is writing about the moment when the words and their constellations open to new text as if the work that has to be done is a work of foretelling: “STICH-O-MAN-CY, Divination of lines or passages of books taken at hazard.” The roll of dice leading to understanding. The instrument is permanently broken. A quartet relation reconstructed. And then the imp is gone.

Imprint

| Artist | Félicia Atkinson, David Grubbs, Susan Howe, Gerhard Rühm, Toni Schmale, Zorka Wollny |

| Exhibition | Speak in Order That I May See You Or Whistle And I‘ll Come To You |

| Place / venue | Christine König Galerie, Vienna |

| Dates | September 13 - October 13, 2018 |

| Curated by | Daniel Muzyczuk |

| Website | www.christinekoeniggalerie.com |

| Index | Christine König Galerie Daniel Muzyczuk David Grubbs Félicia Atkinson Gerhard Rühm Susan Howe Toni Schmale Zorka Wollny |