‘Works of Heart (1974–2022)’ by Sanja Iveković

Works of Heart (1974–2022) begins with Sanja Iveković’s heartbeat and her breathing (or, more precisely, with the documentation of two of her performances, Inaugurazione alla Tommaseo [Opening at the Tommaseo], 1977, and Nessie, 1981). The exhibition is retrospective in nature. At the same time, like the pulse of her heart, Iveković works here and now, just as throughout her career she has been an active protagonist in the unfolding of history. Her works are a chronicle of the last two decades of the former Yugoslavia, followed by Yugoslav wars and the transition from socialism to wild capitalism in Eastern Europe, largely won by mobilizing national sentiments and traditional values. Her recent works, however, take a critical and engaged position on the current state of Europe. Sanja Iveković’s art wants to leave traces in reality; it has a performative power that strives for gender equality, anti-fascism, emancipation of collective memory, and solidarity.

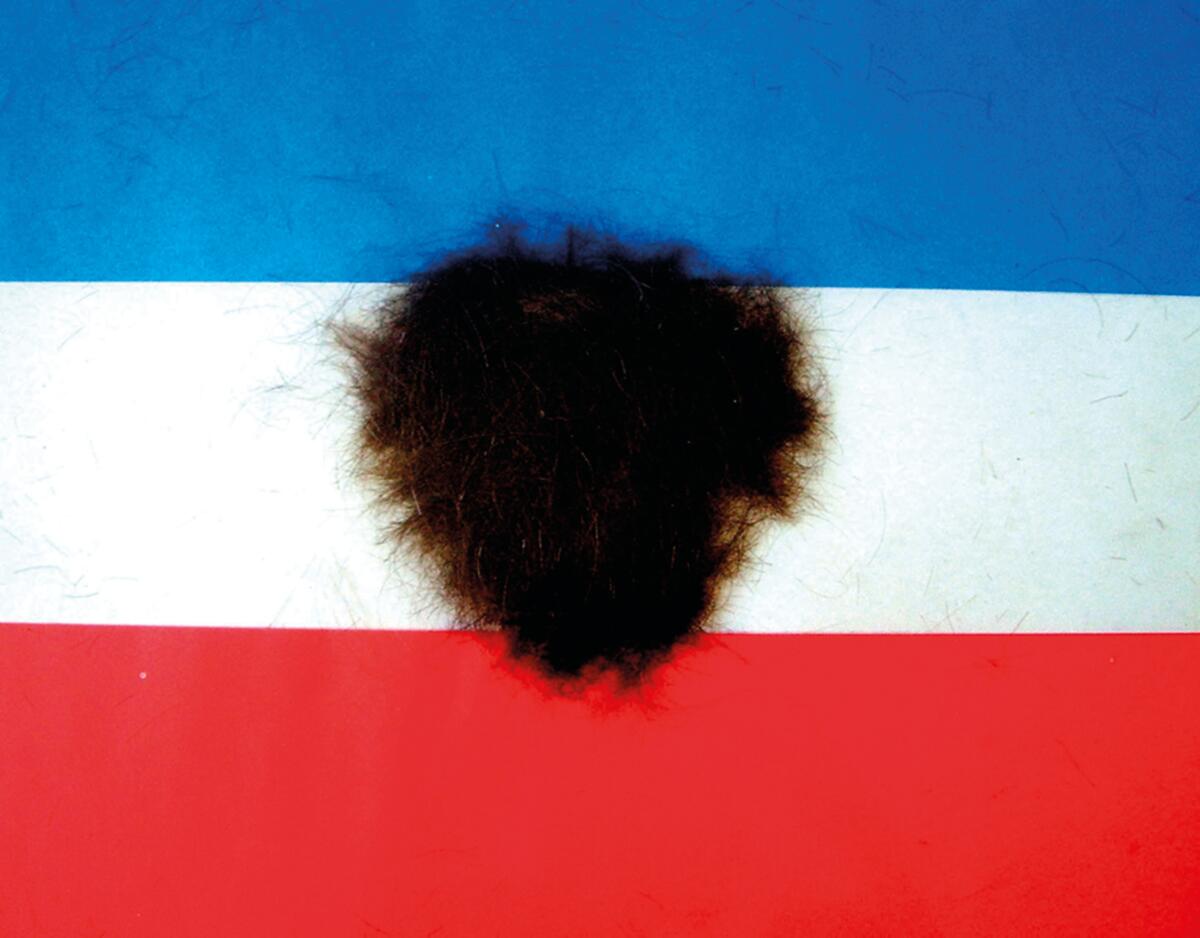

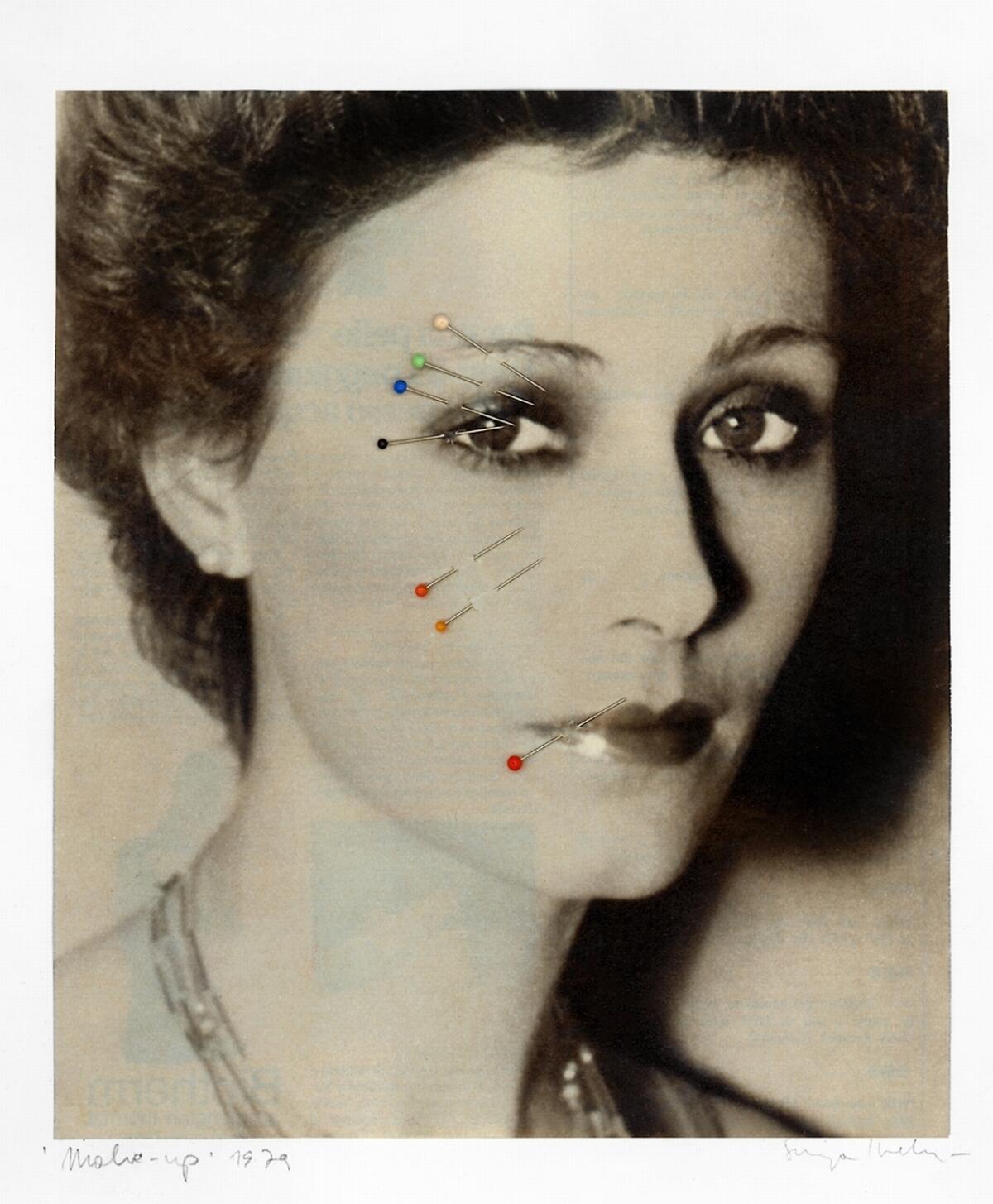

Iveković came of age as an artist in the 1970s in socialist Yugoslavia, a time when abstract male modernism dominated as official art. She resisted „universal” modernist truths from her particular female position, with her own body settling in her performances and videos. In doing this, she did pioneering work in Yugoslavia and beyond. She was also one of the first to approach politics from a feminist position and to strike at the myth of originality by collaging and cutting through newspapers and magazines. This is how her engaged art came about at a time when ideological propaganda had already abandoned socialist realism and was using modernist abstraction in the anti-fascist and World War II monuments that are internationally recognized today. In the former Yugoslavia, her art unmasked both ideological communist and consumer propaganda, or rather what is stereotypically considered ideological and associated with autocratic regimes and the apparent non-ideology of the market itself.

This was done with the help of mass propaganda media and iconography, which she tries to strip of all its constructed meanings. Thus, among other things, her art becomes a tool to look into the empty signifiers that viewers have yet to fill with meaning. That is why her works remain alive—they address us with a media image that has not changed significantly with the passing of time, and, at the same time, demand that we invest our current experience in them. Despite the great social upheavals of the last half century, the media still counts on our narcissism, escapism, and traditional gendered social roles. Iveković propagates a different truth by using the same media, sometimes even by directly incorporating her art into existing magazines and newspapers or into national television programs. In interpreting Iveković’s use of propaganda methodology in her art, we can refer to Jonas Staal, who talks about how different types of power result in distinct forms of propaganda—oppressive and emancipatory.[1] Staal studied different types of propaganda to develop himself as a contemporary emancipatory propaganda artist, to act in service of our collective competence and awareness in building a new world. From the very beginning, Iveković’s art has revealed how different forms of propaganda work, while she herself has become an activist artist who is able to use the power of art for emancipatory purposes.

The activist side of Sanja Iveković’s artistic production is characterized by the direct exchange of experiences and mutual learning, something the US-American activist and theorist Lucy Lippard would call a feminist “intimate kind of propaganda”, which is characteristic of artistic practices based on meetings, different physical encounters, and direct relationships.[2]

Sanja Iveković’s art practice also shows how, at least until recently, Western art magazines operated according to the system of inclusion and exclusion. In the photomontage Women in Art – Žene u jugoslavenskoj umjetnosti [Women in Art – Women in Yugoslav Art] (1975), the artist adds her drawings of Yugoslav artists to the photo portraits of Western women artists published in Flash Art magazine, and thus “includes” the depicted invisible artists in the international art system. Boris Groys says that art from Eastern Europe was excluded from the dominant art system because it was associated with the idea that in socialism all art is about ideological propaganda. But, as he writes, the methods of ideological propaganda are characteristic of Western art, which propagates its power to the masses at major exhibitions and biennials.[3] Contemporary art is, in its own way, the propaganda of Western democracy, which, at least seemingly, allows for the coexistence of different concepts of power. The existing art system seems to take care of the autonomous power of contemporary art, while paradoxically subordinating it to the power of the market. The question is: to what extent can art avoid being trapped in a dominant system and how much can it really change society? Today, Sanja Iveković, like many other artists, draws attention to excluded histories and marginalized social groups. But the inclusion of the hitherto excluded paradoxically only strengthens the existing art or any other system. Sanja Iveković seems to be aware of all these pitfalls, as she is constantly trying to increase the visibility of the unseen, but on the other hand, she is trying to keep it opaque; by never trying to codify the invisible in her works, it exists as the invisible power of the real, as something that does not always have a recognizable identity. The neglected and abused women in her works become visible through their stories, but not through their identities. Just as Iveković was critical of socialist society, today she is critical of capitalist society, but her critique doesn’t propose a new ideological or marketing story. On the contrary, with her emancipatory propaganda, she constantly points to the gaps in the existing methods of oppressive propaganda and thus propagates the real, that which, according to the theory of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, cannot be depicted nor verbalized.

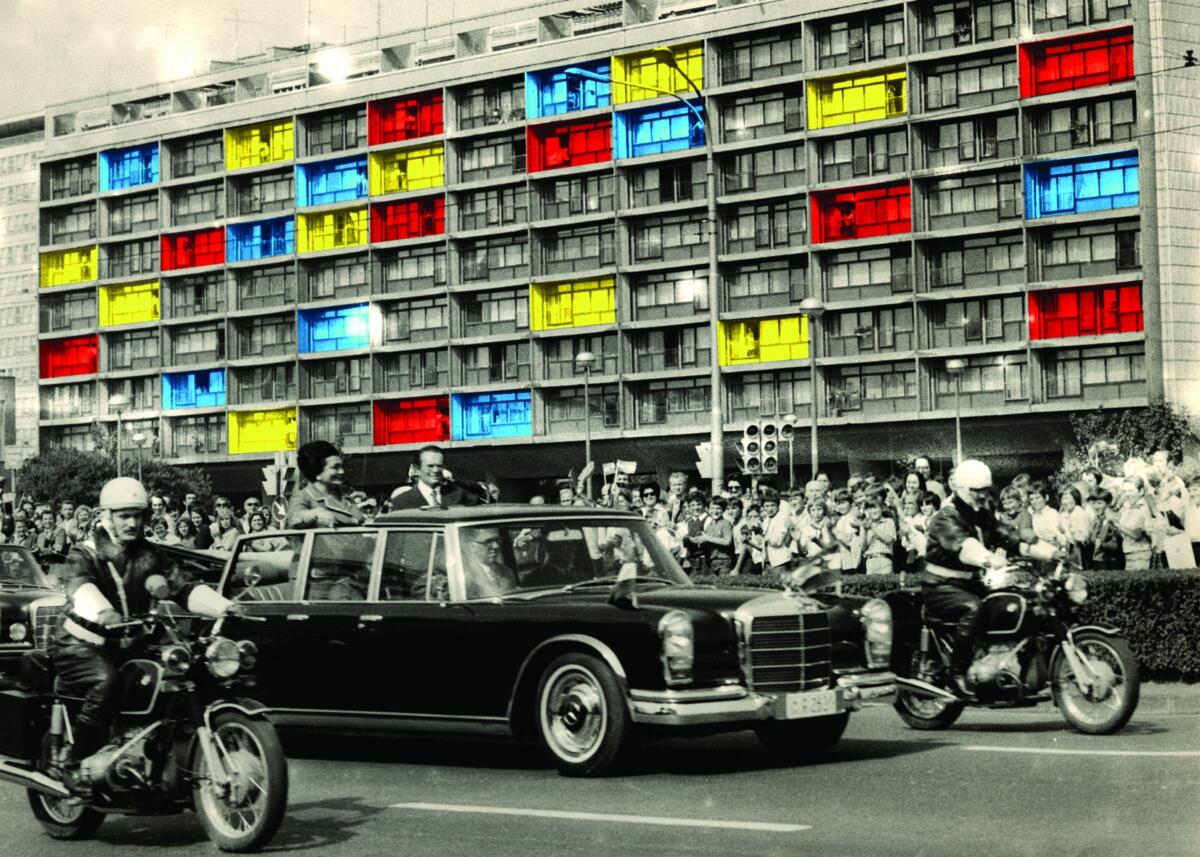

In 1975, when Iveković made her iconic work Dvostruki život [Double Life], consumerism, individualism, and competition had already replaced socialist values based on the cult of work and solidarity. Yugoslav society had been living a double, schizophrenic life, somewhere between socialism and the market economy, between ideology and reality. Iveković started working during the transition from a society of discipline to a society of control, and, with her dual structure of work, she proves that there has long been no difference between public and private. Hidden behind the concrete parapet of her balcony in the now legendary performance Trokut [Triangle] (1979), she was counting on surveillance, expecting to be spotted by a police officer surveying Josip Broz Tito’s parade, which was taking place on her street at the time. In her interventions in the media, in her collages, videos, photo-graphs, and performances from the 1970s and 1980s, Iveković reveals the paradoxes of socialist society, which she considers a society of conflicts and which she follows even after the fall of socialism. As is evident from her work, these conflicts were not resolved in the 1990s upon the dissolution of Yugoslavia. On the contrary, they have only intensified since then. In the 1990s, a war broke out in the territory of the former Yugoslavia, fueled by nationalist sentiments, and patriarchalism returned to the public sphere. Violence against women in both public and private spaces was growing. In view of all this, Sanja Iveković increasingly took an activist position in the 1990s and worked directly with survivors of violence and the organizations that serve them. In 1998, she began work on the long-term Ženska kuća [Women’s House] project, which has been implemented in collaboration with numerous women’s organizations that run shelters for abused women in different countries. Out of this grew the Ženska kuća (Sunčane naočale) [Women’s House (Sunglasses)] (2002–ongoing) project. Both are collaborative projects of intimate propaganda dealing with violence against women, involving workshops and close collaboration with women’s shelters and survivors of violence, which appear in the gallery context with posters, postcards, videos, and installations.

Through her activism, two principles of Iveković’s work become increasingly evident: the deconstructive, which unmasks how oppressive propaganda and its mechanisms of manipulation work and what interests stand behind it; and the constructive, which empowers women, who thus become the subject of their own lives. Her art becomes a safe territory where survivors of violence dare to tell the truth without fear. Emancipatory propaganda is present in both of her two modes of working: one intended for the broad audiences and often made for public space; the other, in direct work with women and their organizations, which function as intimate propaganda. And in many of her works, these two methods are intertwined within the same project.

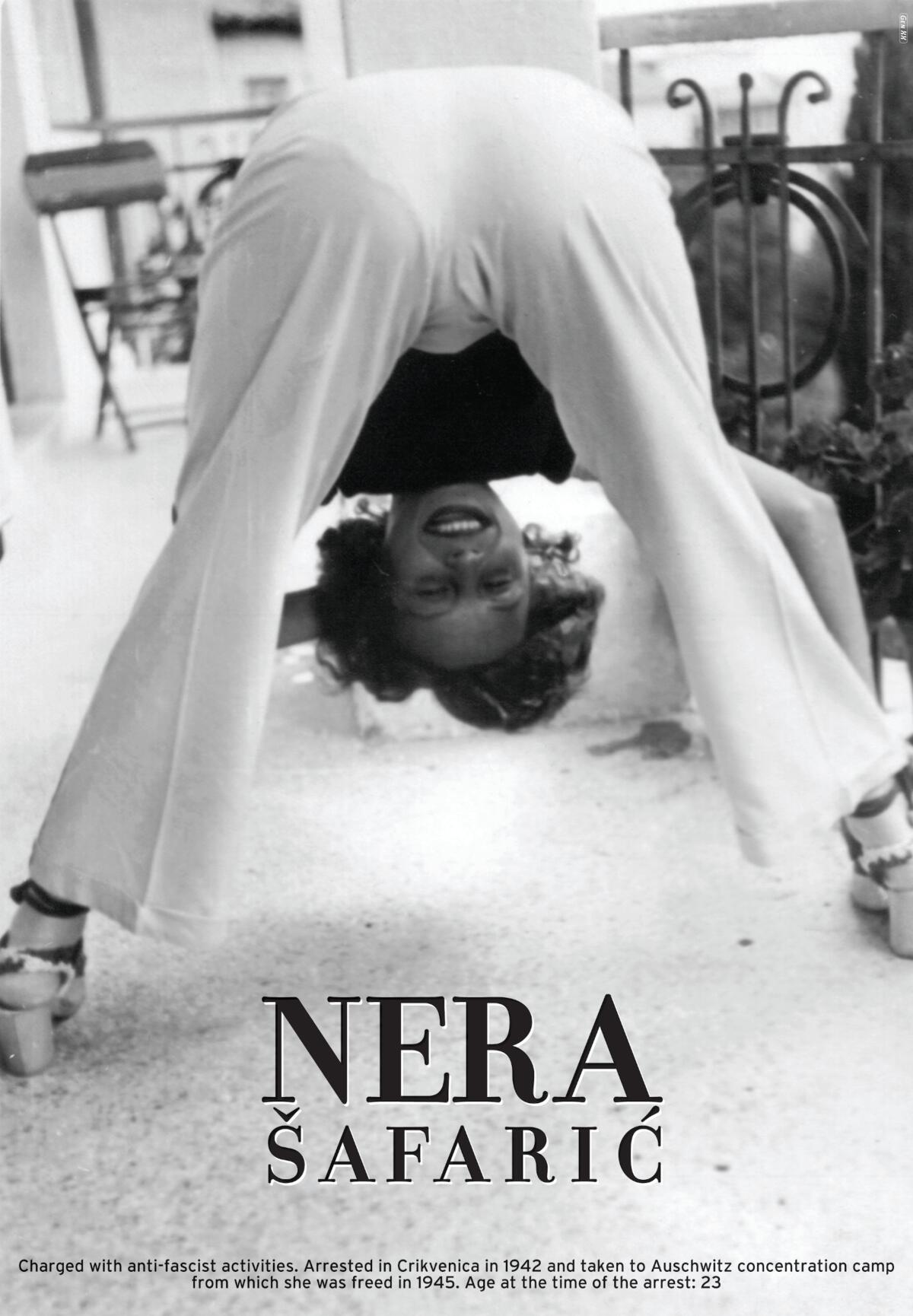

With her works, Iveković builds different narratives, the narratives of those who were expelled from history: anti-fascist heroines, refugees, Romani and Sinti. Her iconic work Gen XX (1997–2001) appropriates the presentation of famous fashion models in the media to spread knowledge about women who fought against fascism in Yugoslavia in World War II. In 2005, in the small Austrian town of Rohrbach, she re-enacted the situation represented in a photograph showing Romani and Sinti waiting to be transported to a concentration camp. The Rohrbach Living Memorial project (2005) refers to the absence of memorials dedicated to those Romani and Sinti who were victims of the racist policies of the Nazi regime and its extermination program in Austria.

Her works try to return the forgotten and repressed to collective memory, and Sanja Iveković works similarly with her own personal memory. The Works of Heart (1974–2022) exhibition is also about “me and my mother”. The mother-daughter relationship is the subject of some of the works in the show, but this personal dimension of her retrospective can also be misleading, as this “me” is constantly placed in the context of modern media and is thus cynical about the very existence of an authentic self. In the performance that the artist prepared for this exhibition in collaboration with dancer and choreographer Mitja Obed, she stages a dance that deconstructs stereotypical ideas about the mother-daughter relationship but also about performance as a medium. An important part of this project is the book of poems by her mother Nera Šafarić-Iveković, who is also one of the heroines of Gen XX and who was arrested as a young communist in 1942 and taken to Auschwitz. The title of one of her poems is Jao si ga onome tko se boji duhova [Woe betide anyone who is afraid of ghosts], which could be associated in the context of this exhibition with loss, disappearance, and unrepresented, erased histories.

Works of Heart (1974–2022) talks about the crises of today: refugees, pandemics, and indirectly touches on the current war in Europe. The title of the exhibition is based on her work Works of Heart (2001), which includes a page from The New York Times that juxtaposes an image of the 1994 Sarajevo market massacre and an advertisement for a woman’s necklace with a heart-shaped pendant. Similarities can be observed in the media today, as the war rages in Ukraine.

Sanja Iveković’s art practice proclaims that we must face the real of today’s Europe. In 2006, during the Austrian presidency of the EU, she made a poster portraying a mummified Lenin with the inscription “Achtung, Europäer! Wir Kommen!” [Attention, Europeans! We are coming!]. So who is coming to Europe today? Time and time again, we come ourselves, we, who as we are, have never left. That is to say, we see ourselves in the new-comers, we project our own discomfort and fear of the unknown onto those who come to us from elsewhere. With her art, she advertises the real: that which is never said in ideological or commercial propaganda and is hidden in the gaps of the dominant symbolic order. At a time when our world is dominated by various conflicts of oppressive propaganda, it is important to establish alternative channels of emancipatory propaganda. Contemporary art, such as the art of Sanja Iveković, can play a big role here.

Zdenka Badovinac, curator

The text was originally published in the exhibition guide accompanying the exhibition “Sanja Iveković. Works of Heart (1974–2022)” curated by Zdenka Badovinac at Kunsthalle Wien. You can read the extensive exhibition guide here.

[1] Jonas Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019)

[2]Staal, Propaganda Art, p. 118.

[3]Boris Groys, Art Power (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), p. 8.

Imprint

| Artist | Sanja Iveković |

| Exhibition | Works of Heart (1974–2022) |

| Place / venue | Kunsthalle Wien |

| Dates | 04.10-12.03.2022 |

| Curated by | Zdenka Badovinac |

| Index | Boris Cvjetanović Kunsthalle Wien Marko Ercegović~ Mitja Obed Rada Iveković Sanja Iveković Zdenka Badovinac |