Image 1: The Poland-Belarus border is over 400 kilometer long, formed by dense forests with swamps.

We are publishing the reportage prepared by Slovakian journalist Anna Jacková and photographer Michaela Nagyidaiová to highlight the manufactured crisis currently happening at the Polish-Belarusian border. We stand in solidarity with the victims and volunteers of this political catastrophe.

We head to the forest where three Kurdish boys are waiting for us. There may also be police, the army, or smugglers. One thing is for sure, no one is safe. Time is of the essence. A humanitarian crisis is occurring on the Polish-Belarusian border, testing the moral boundaries of its people.

An old country house close to the Polish-Belarusian border now serves as a base and warehouse for volunteers and activists providing aid in the forests. Five people, Agata, Kassia, Marek, Zuzana, and Wiktoria sit in the house in November 2021. They have decided to travel from different places and countries to the Podlasie region of Poland, where a humanitarian crisis has been unfolding since August 2021.

Every evening, the group evaluates how the day went and how they felt. Sitting at the table, Wiktoria interrupts the conversation: “Can you hear that? That’s the army.” Armored vehicles roar outside the window. They agree that the first intervention was successful, the second was not. When an intervention is a success it means that one group of volunteers or activists managed to locate migrants in the forests and give them at least a hot soup, tea, water, or dry clothes. The volunteers can’t do much more because they could face charges of smuggling. The police arrived during their second intervention, which is why it turned out to be an unfortunate mesh of events. Most likely, the migrants that were found there were taken back to the Belarusian side of the border by the police or border patrol.

Intimidation of activists and volunteers helping people in the forests has been occurring here for months. The more visible you are, the clearer target you become for the armed forces, which have been using aggressive methods when interacting with migrants, as well as the right-winged radicals based in Podlasie.

Poland has been breaking international humanitarian laws since the beginning of the crisis. A person who crosses the border without paperwork and applies for asylum is entitled to have his/her/their application assessed. However, volunteers regularly receive reports from migrants detained by Polish border guards, who were exported back to Belarus without having any assessment. The pushbacks are normally illegal, but the Polish government has found a way to circumvent the amendment, as explained in a report published by Grupa Granica, “According to the new Regulation, persons who have crossed the Polish border illegally are to be delivered back to the border, no exceptions are foreseen for people declaring they want to ask for protection under international law.”

Belarusian soldiers often use threat and force when moving people across the border back to Poland. Whole families, primarily from Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, are wandering through freezing forests and undergoing dozens of pushbacks. The Polish soldiers often divide them when exporting them back to the Belarusian side. The landscape of the more than 400-kilometer border is densely forested and swampy.

Image 2: We were staying in Hajnówka, approximately 15-20 minutes by car from the border with Belarus.

Image 3: A few years ago, the Polish production of HBO first screened the tv series crime hit ‘Wataha’ (The Border) about border guards from the Polish-Ukrainian environment. Actor Marek Kalita (portrayed on the image) then played the role of a prosecutor there. This time, however, we are talking about the Polish- Belarusian border, where he came to help as a volunteer. “My guilt grew so much that I had to do something about it,” says Kalita.

“I know that for a while in Poland, laws have not been applying to people in the forests. They have no rights, even though they should have them by law. Poland also violates

the rights of its citizens, because the government interprets the state of emergency in such a way that it does not allow journalists or humanitarian workers to enter the border zone. This is the paradox of the whole situation.”

Image 6: We head to the forest, where three boys from Iraq are waiting for us. There may also be police, the army or smugglers. One thing is for sure, no one is safe. Time is of the essence. A humanitarian crisis is taking place on the Polish-Belarusian border, testing the moral boundaries of its people.

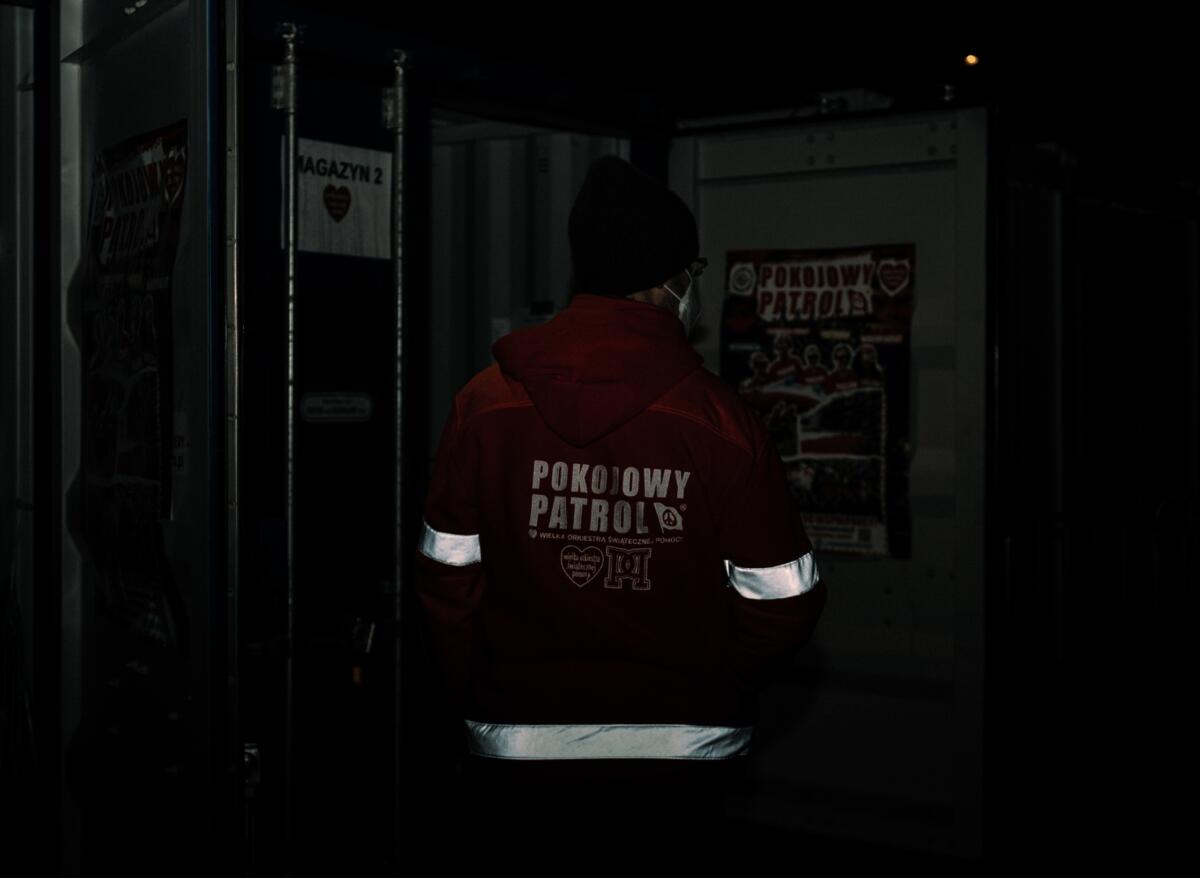

Image 7: Janek took some days off from his regular job in Warsaw to join Pokojowy Patrol for a few days.

Image 8: Pokojowy Patrol (Peace Patrol), a group of volunteers and activists based in Michalowo. They have been collecting items from sanitary products, tents, to shoes, warm clothes, or food – all of these items are being distributed to the people at the border during activist interventions. People from all over Poland have also been donating items and volunteers from all over the country gathered here to help out.

Local school has been letting Pokojowy Patrol work from their premises, giving them outdoor space for multiple containers full of items for people at the border. The volunteers from Pokojowy Patrol take turns in shifts but there is always someone there, day and night.

Image 9: Pokojowy Patrol (Peace Patrol), a group of volunteers and activists based in Michalowo. They have been collecting items from sanitary products, tents, to shoes, warm clothes, or food – all of these

items are being distributed to the people at the border during activist interventions. People from all over Poland have also been donating items and volunteers from all over the country gathered here to help out. Janek took some days off from his regular job in Warsaw to join Pokojowy Patrol for a few days.

Image 10: Mariusz from Pokojowy Patrol based in Michalowo. Pokojowy Patrol (Peace Patrol), a group of volunteers and activists based in Michalowo. They have been collecting items from sanitary products, tents, to shoes, warm clothes, or food – all of these items are being distributed to the people at the border during activist interventions. People from all over Poland have also been donating items and volunteers from all over the country gathered here to help out.

Images 11&12: Image captured in a small village of Bohoniki, where the Tatar community practicing Islam has lived for several centuries. As we walk through the village, there is a mosque right by the road, and opposite we see a Muslim pilgrim’s house.

There is silence everywhere. Parked cars stand on both sides of the

road, journalists with cameras and camcorders flicker everywhere. A small funeral van arrives, from which a small white coffin is being removed. Imam Aleksander Ali Bazarewicz prays, the funeral of a premature baby of 27 weeks takes place without parents, the mother is in critical condition in the hospital at that time.

Image 17: “There are a lot of right-wing extremists. A few of my friends have already received threatening messages. Some help people in the forests, others persecute them, “says Paulina (photographed here), who is a citizen of Bialowieza that has been declared as a part of “exclusion zone”, as it’s located very near the border (approximately 5 mins by car).

She speaks to us in the garden of the church in the town of Hajnówka, in front of which hangs a huge poster in support of police officers and soldiers stationed at the border with the popular hashtag #MuremZaPolskimMundurem that translates to “A Wall Behind the Polish Uniform”.

Paulina’s face is concealed using flash, for her safety and security.

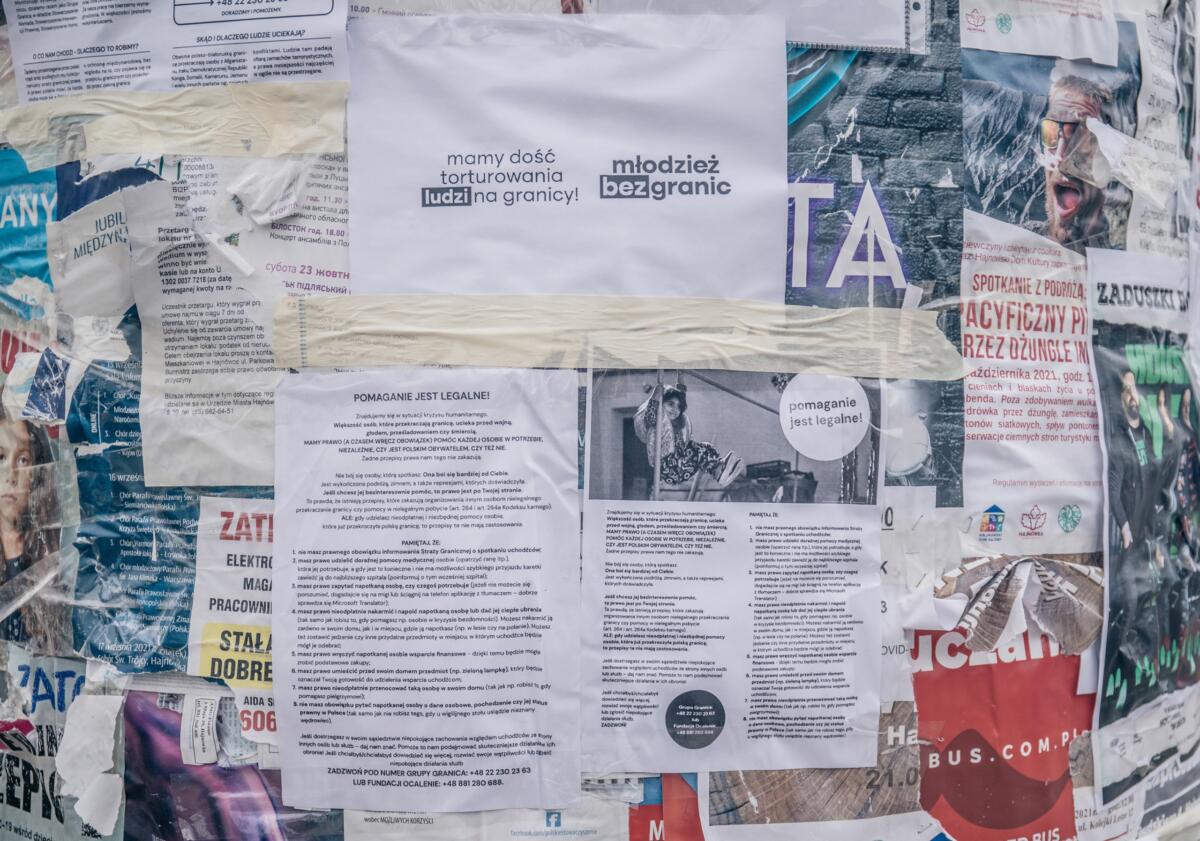

Image 18: Help is legal. This is one of the leaflets that we often saw within the border areas. Since the beginning of the crisis, Grupa Granica’s network of 14 non-profit organisations has been helping not only people in the forests, though also local people, who live in the exclusion zone or just in its nearby surroundings. Grupa Granica is made up of activists and volunteers.

Image 20: A car of the border patrol, which used to stop us multiple times during the day if we were getting too close to the exclusion zone. We were frequently asked to open the trunk and windows of our car for the patrol, other times we had to identify ourselves and answer what we were doing in the area and why we were there.

Image 21: Locals living within the exclusion zone have to identify themselves and show proofs of living/ working there to the border guards or police if they wish to leave or come back to the area. No one else is allowed to enter the zone.

The following reportage was written originally in Slovak by Slovakian journalist Anna Jacková, and was translated and photographed by Slovakian photographer Michaela Nagyidaiová for fjúžn SK.

To know more about what’s been occurring at the border, you can also check @salamlabpl, @grupagranica, @fundacjaocalenie.

The reportage was created with financial support from the European Union and The World Between the Lines initiative.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Author | Anna Jacková |

| Artist | Michaela Nagyidaiova |

| Title | Photo Story: Volunteers at the Polish-Belarusian border work in secret |

| Photos | Michaela Nagyidaiova |

| Website | www.michaelanagyidaiova.com/ |

| Index | Anna Jacková Michaela Nagyidaiova |