Adam Mazur: Tell me more about the title of the show at the Arton Foundation, Phony Smile.

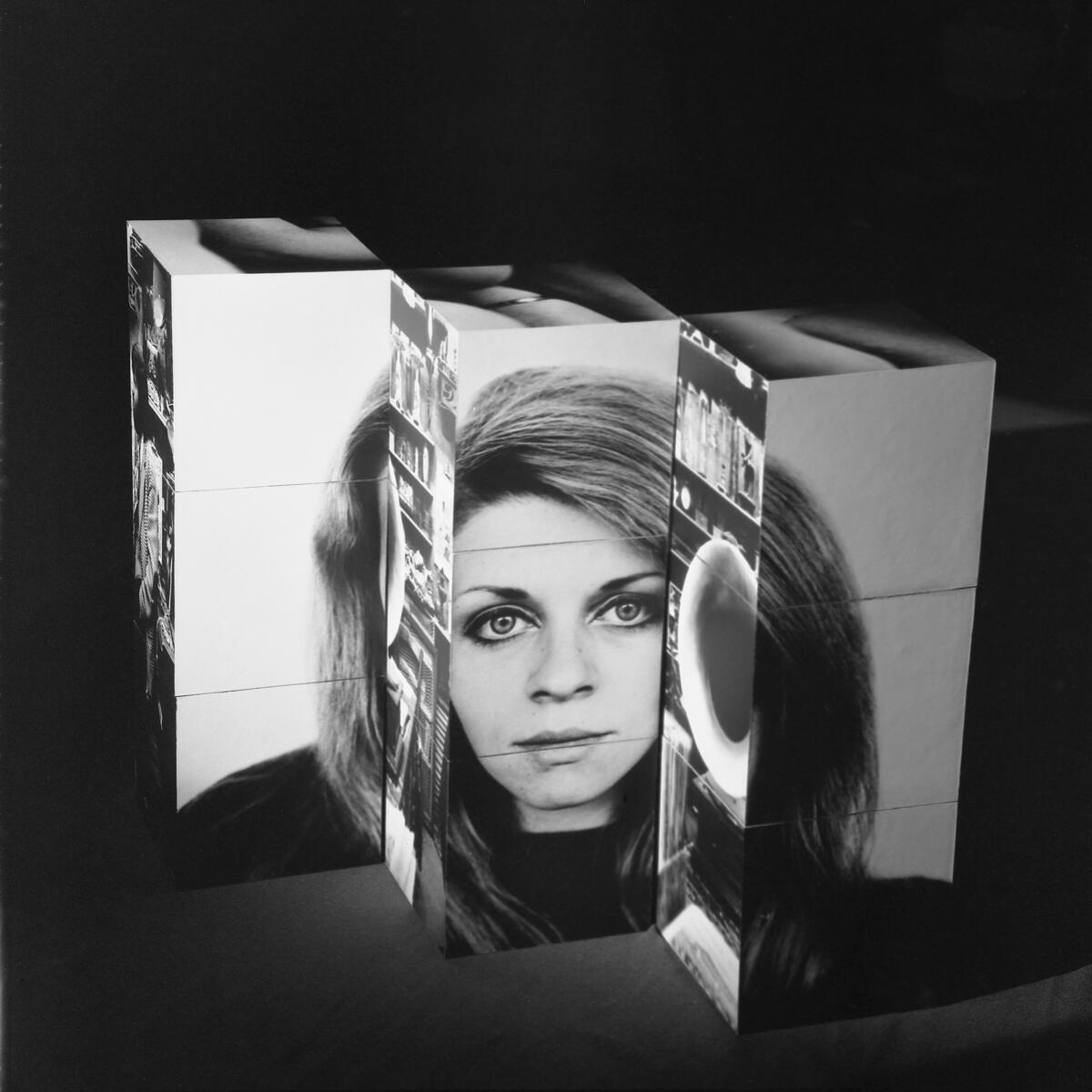

Sandra Križić Roban: The title of the exhibition is an intimate homage to Edita Schubert, an artist whose works appear in the exhibition, yet whose name is rarely mentioned in standard overviews of conceptual photography in Yugoslavia, or of photography in general. Primarily because, during the 1970s, which could be regarded as the height of conceptual art, Schubert was working in other media. However, her first significant photographic works appear in 1977. As for the title itself, it refers to stickers – more specifically, the two series titled Real Smile and Phony Smile – which the artist used to tackle the motif of self-portrait in an unusual, even unexpected manner. Employing the simple method of applying stickers in an exhibition, as well as public spaces, she problematised the theme that she has engaged since the start of her public appearances. The self-portrait, in the manner she envisions it, is always imbued with witty and self-ironic play, while, in these series, it implies a deconstruction of the notions of the original and the reproduction. By means of this piece, as well as in her work in general, Schubert literally expanded the field within which we often too literally place artistic practices. She used the so-called ‘low-cost’ material, that is, photocopies of photographs, which, among other things, examine the issue of reproducibility and the status of the original.

What would be so radical about the language used by artists you are researching and exhibiting?

The radical properties of this language should firstly be considered in relation to the local context and the position that this language attempted to claim, including photography. That is, regardless of the exact historical moment, there were great variations in the perception of the basic notions employed in photography. The artists who worked in the medium in the 70s and 80s – whose works are presented to the Polish public in this exhibition – opened themselves up to the introduction of intellectual concepts in photography through their work, thus radically diverging from the typical positions of modernism. Realising that this concept surpasses the choice of the medium, since the 1980s there have been efforts within the local community to change the dominant discourse about so-called art photography and photography used as a media by other artists, as it is often termed in institutional contexts. However, we should not disregard a considerable number of photographers who operated almost exclusively in the domain of photo clubs, as well as those who attempted to rise above amateur circumstances by joining some of the professional associations, such as the Photographic Section of the Croatian Association of Artists of the Applied Arts. Most of the photographers had amateur status but at the same time possessed an acute awareness about their own artistic accomplishments. Some of them earned their title of masters of photography mostly thanks to the number of international exhibitions to which they submitted their works. At the same time, criticism was perceived in a negative light, even personally, while any sort of deviations from the “golden standard” were met with particularly negative feedback, especially when the works in question came from artists who were not photographers and did not belong to any of the aforementioned groups.

Even though photography criticism was scarce, it is interesting to read a few openly hostile texts directed at the series of exhibitions titled New Photography and the idea behind the magazine Spot (1972-1978), which centred precisely on conceptual approaches to photography. This sharply polarised environment persisted for quite some time, and, even today some of the older colleagues do not regard conceptual photography as relevant in any way. Thus, this “radical” idiom, through which they question the established status of photography and/or advocate its change, is specific to a relatively small group of authors, willing to do away with the traditional functions of photography, its aesthetic, relationship to reality, etc.

You write about Croatian photography and its specific quality. How would it be related to Yugoslav heritage?

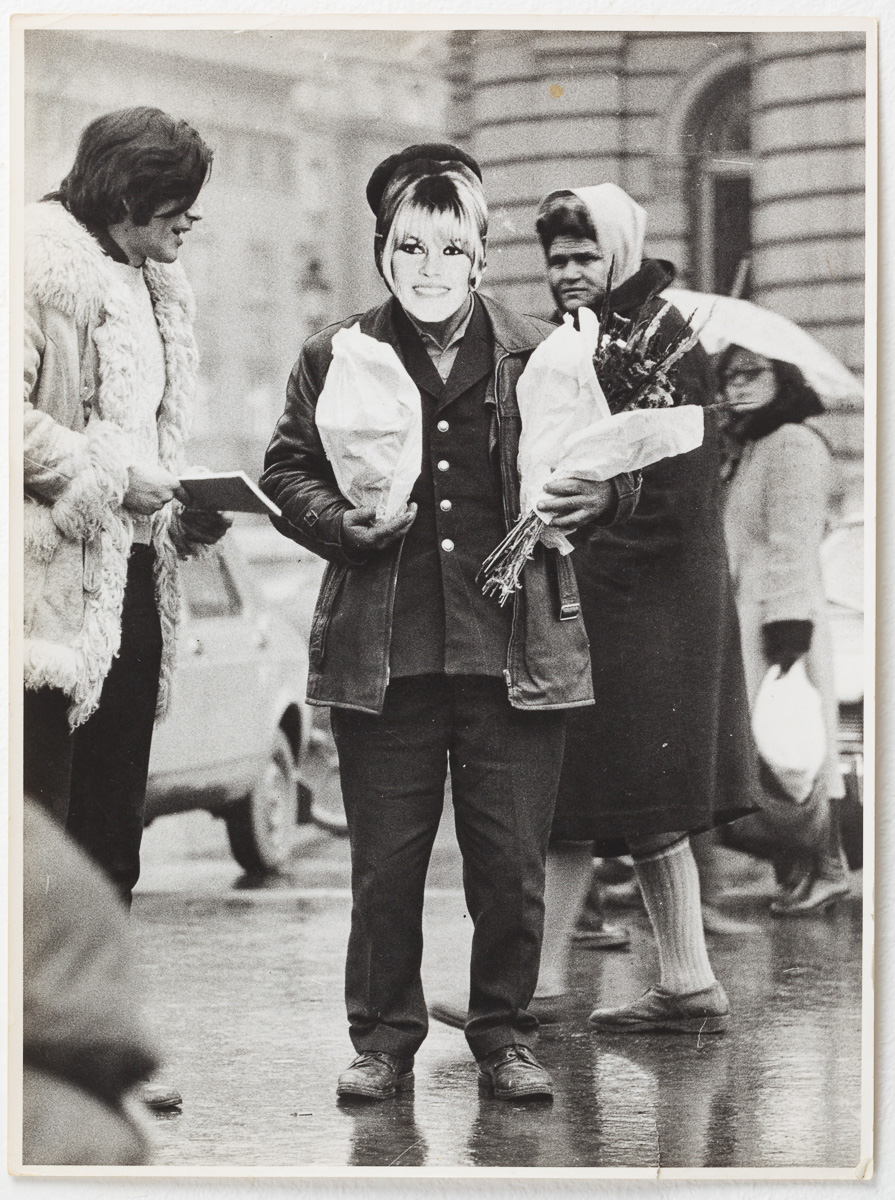

The greatest portion of material that I have researched is related to the circumstances in Croatia. The Serbian scene is equally important and should be examined further in a possible future overview. There were fewer participants actively working in the Slovenian scene, with the unmistakable exception of the so-called Maribor Circle. Certain aspects are discernible by observing the exhibition series titled New Photography, which was jointly organised by the Modern Gallery in Zagreb, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, and the Rotovž Salon in Maribor (the four exhibitions were held in 1974, 1976, 1980, and 1984). The critical, “non-aesthetic” photography was showcased precisely by these more progressively oriented institutions. here were also instances in which photography made an appearance in public spaces, mostly in Zagreb and Belgrade, especially in the case of photographic performance works by the Group of Six Artists, namely Željko Jerman (1949–2006) and Vlado Martek (1951). In addition, another important figure that should be mentioned is Tomislav Gotovac (1937–2010), who belonged to a slightly older generation andwho, on a symbolic level, connects the Zagreb and Belgrade scenes through a series of photographs and series, i.e. sequences, in which their essence follows the logic of a film frame.

Modest production conditions and the “disregard” with which the artist themselves treated the medium, to an extent influenced the opinion that this was not “proper” photography. It was not possible to fit it into any of the existing spheres, explain it or market it, all of which contributed to the isolation of this important body of work. Precisely for this reason, Spot magazine was crucial in lending visibility to the changes that marked the 1970s, since it promoted current and experimental works and visual explorations, which it tried to put into context with similar developments in different European countries. The way in which photographs published in Spot communicated with their readership speaks in favour of encouraging new possibilities, of employing and problematising the medium which was, among other things, used to try to critically examine the environment and the circumstances for survival of the progressive artistic context of photography. The selection of international authors belonging to different generations and employing diverse artistic expressions, with an early interest in the theoretical examination of multimedia artistic practices, in experimentation, such as generative photography, the use of Xerox and other ideas and directions of “new photography,” engendered a studious and uncompromising concept for the magazine. The composition of the magazine’s editorial board also revealed fourkey locations – Zagreb, Belgrade, and in addition to Maribor, Ljubljana, which were the centres of what we today perceive as the legacy of conceptual photography.

You are one of the founders of the Office for Photography. What is the concept behind this organisation?

We could say that it varies. We started out primarily as a website https://croatian-photography.com/ focused on promoting different photographic approaches. With time, we introduced the exhibition programme at Spot Gallery, which was named precisely in honour of the eponymous magazine. The programme, which has expanded with time, is organised at a private gallery space and often includes collaborations with other associations and institutions in Croatia, the region and beyond. At the same time we initiated our publishing house through which we have published monographs of several authors. Two years ago we launched the magazine Fototxt which publishes texts and conversations related to our exhibition programme or with artists with whom we collaborate or whose work we follow and support. We are also collaborators on several European projects, primarily because they have enabled us to perform further research for which we simply do not have the funds, whereas these initiatives have encouraged us to expand our own project programme at the national level. For quite some time our activities have far surpassed our human and spatial capacities; aimed at creating a space of conversation and examination of innovative and experimental practices primarily in the field of photography and related media. We organise workshops, panel discussions and talks, striving to make up for lost time in a context in which a central institution devoted to photography does not exist. And, where many things are at the mercy of neglect and loss, or, are models of arbitrary management that are completely counterproductive to any kind of knowledge development.

We know quite a lot about the historical importance of post-Yugoslav and Croatian photography. How would you describe the present day condition of this field?

The situation is much better since the establishment of the graduate programme in Cinematography at the Academy of Dramatic Art. I would say that for many generations this has come too late, but also, that the general forlorn state of affairs has to do with the indolence of the environment. However, thanks to different associations, as well as to certain public institutions, there have been some positive changes. Nevertheless, since a central institution – a museum of photography – does not exist, even we are sometimes not aware of all the initiatives in the field. Some of the artists have opted for international careers, which is perfectly understandable. I know that for many artists in this area, as well as the entire field of culture for that matter, things are not easy. The funds being invested in this sector are insufficient and artists often have to resort to commercial jobs, while their artistic work is left on hold. In addition, there are no commercial galleries that participate in international fairs, which is where it would be possible to come into contact with both private collectors and institutions, while for those of us who operate within artistic organisations this is impossible to achieve. It is a shame that on the national level, there is no system that could assist with the promotion as is the case, for instance, with the work of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute. “Small” nations and languages need a structural system of support, the encouragement of cooperation with foreign institutions, financial help for the translations of what we publish, etc. Without all of this, too much falls on the artists themselves, who, just like their older colleagues, find different ways of coping. Given the quality of a host of young and middle-generation artists, I believe that there is much room for improvement. In that regard we are happy that this exhibition has been recognised and has received support from the Ministry of Culture and Media of the Republic of Croatia, without which it simply would not have been possible.

Translation from Croatian into English: Andrea Rožić

Imprint

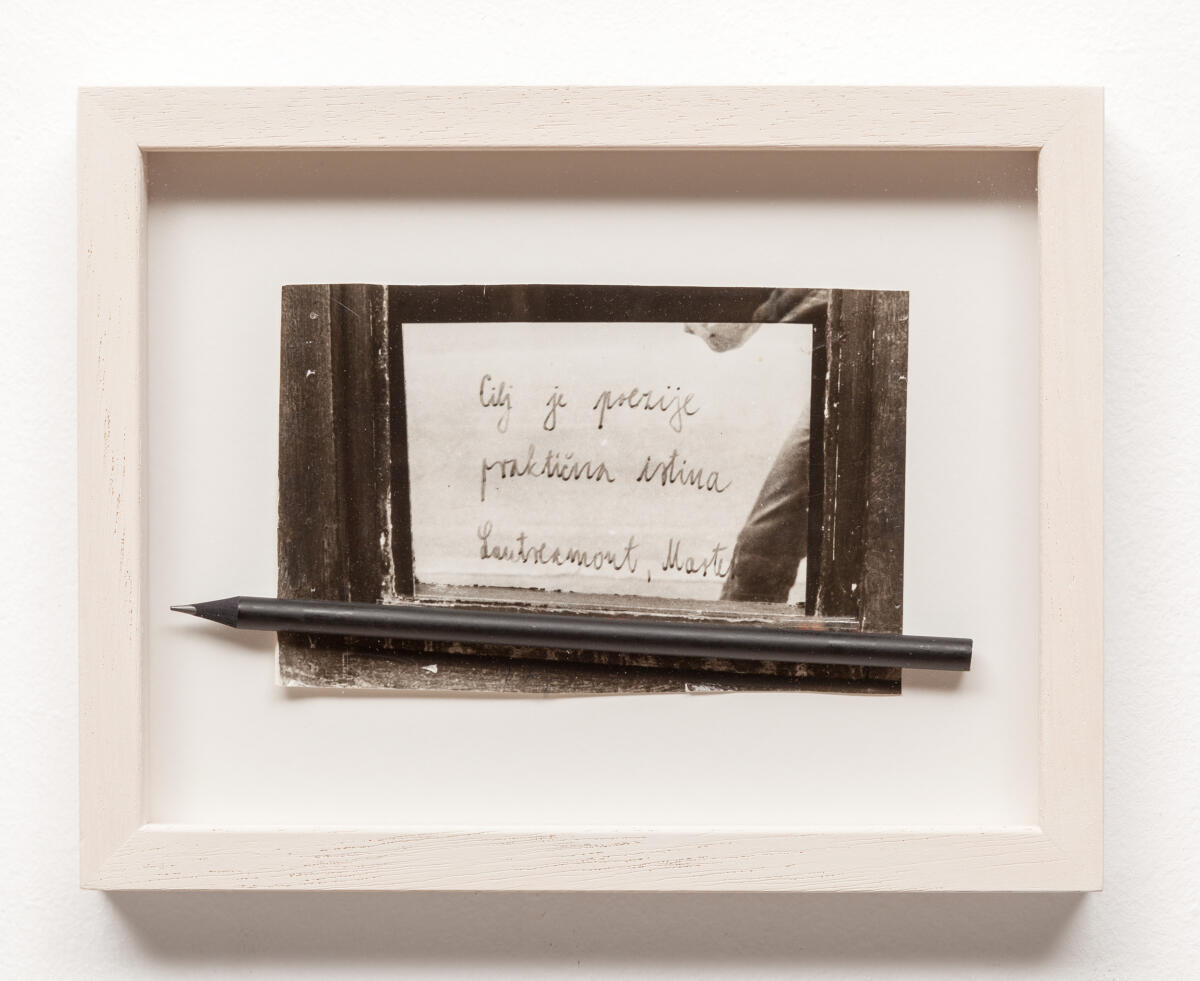

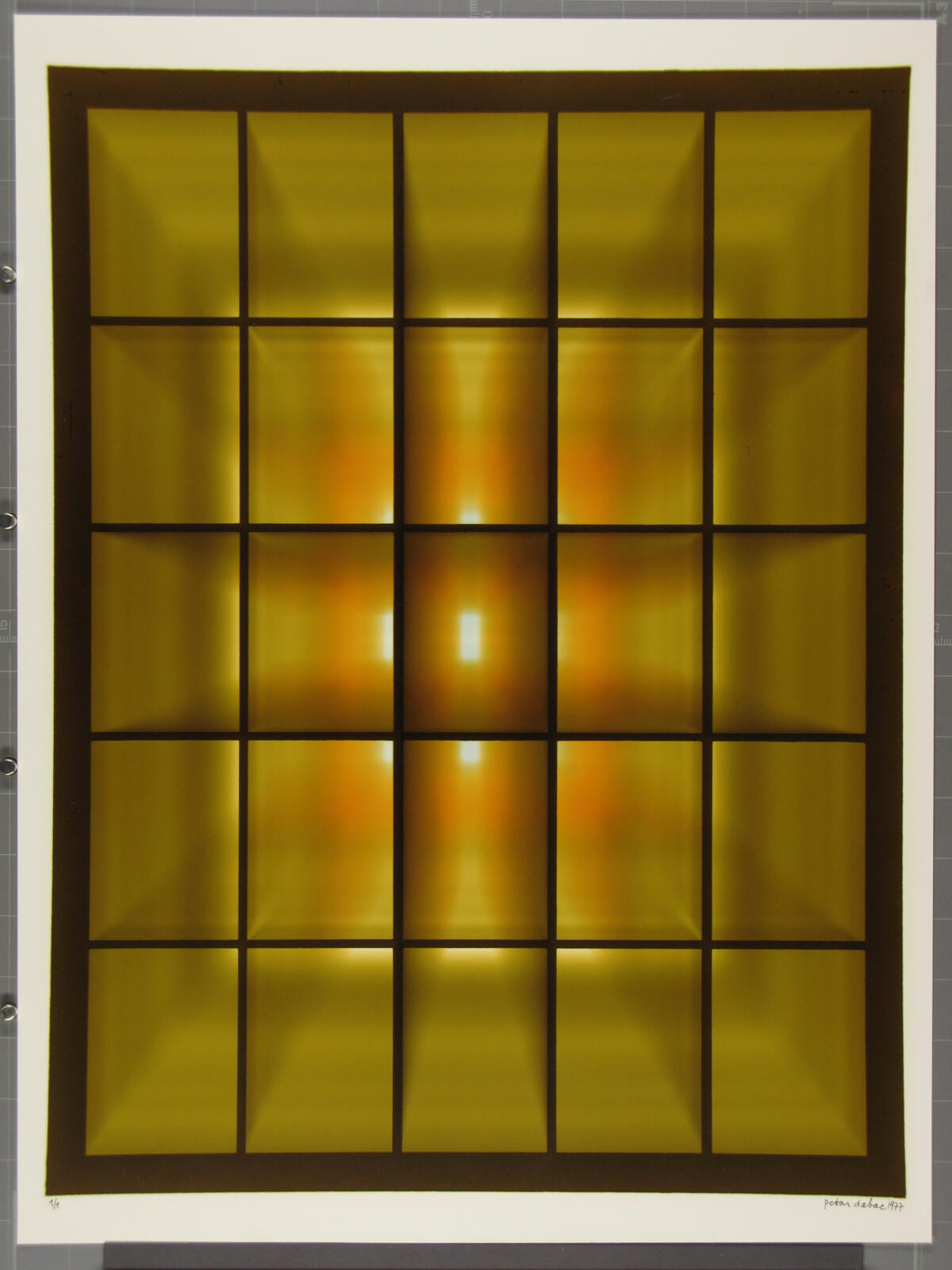

| Artist | Edita Schubert, Željko Borčić, Petar Dabac, Željko Jerman, Vlado Martek |

| Exhibition | Phony Smile |

| Place / venue | Arton Foundation, Warsaw, Poland |

| Dates | 17 January 2021 (opening) |

| Curated by | Sandra Križić Roban |

| Website | www.fundacjaarton.pl/ |

| Index | Adam Mazur Arton Foundation Edita Schubert Petar Dabac Sandra Križić Roban Vlado Martek Željko Borčić Željko Jerman |