Oliver Ressler is a multimedia artist based in Vienna whose work blurs boundaries between art and activism, aiming to bring to light different kinds of alternatives for the economy or society. At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, Ressler brings together his entire body of work focused on climate breakdown, for the first time.

The Croatian audience is not so familiar with your work. If you had to present it in a few words, what would they be?

I am an artist and filmmaker who carries out works on economics, racism, climate breakdown, forms of resistance and social alternatives. The show at MSU comprises films, a multi-channel video installation, a large-scale drawing, a painting, photographic works, lightboxes, banners and sculptural pieces. I am an artist who works closely with social movements.

The title of the exhibition presented at MSU, Zagreb is Barricading the Ice Sheets. How does one barricade the ice sheets?

The title Barricading the Ice Sheets refers to the enormity of what the climate movement faces and the scope of what it sets out to do. To barricade ice sheets as they melt is physically impossible. But the movement is attempting something historically unprecedented, because the planet has never in recorded human history confronted so absolute of a threat. The title, with its semi-surreal quality, points to the enormity of the stakes. In the heart of the exhibition at MSU we see a 6-channel video installation; each projection focuses on a central event of mass civil disobedience in the context of the climate justice movement. Grouped around this major piece on blockades of open-pit lignite mines, coal harbors, and airport expansions are several films that establish a space for what the theorist and activist Marco Baravalle in regard to my work has described as “the non-cinematic time of organization”.

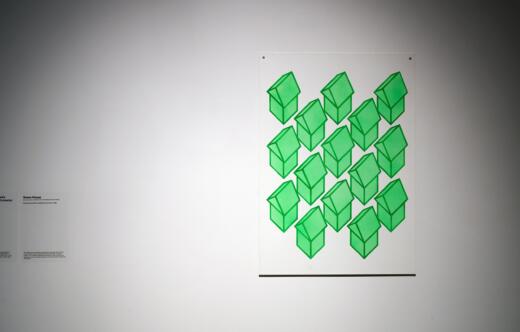

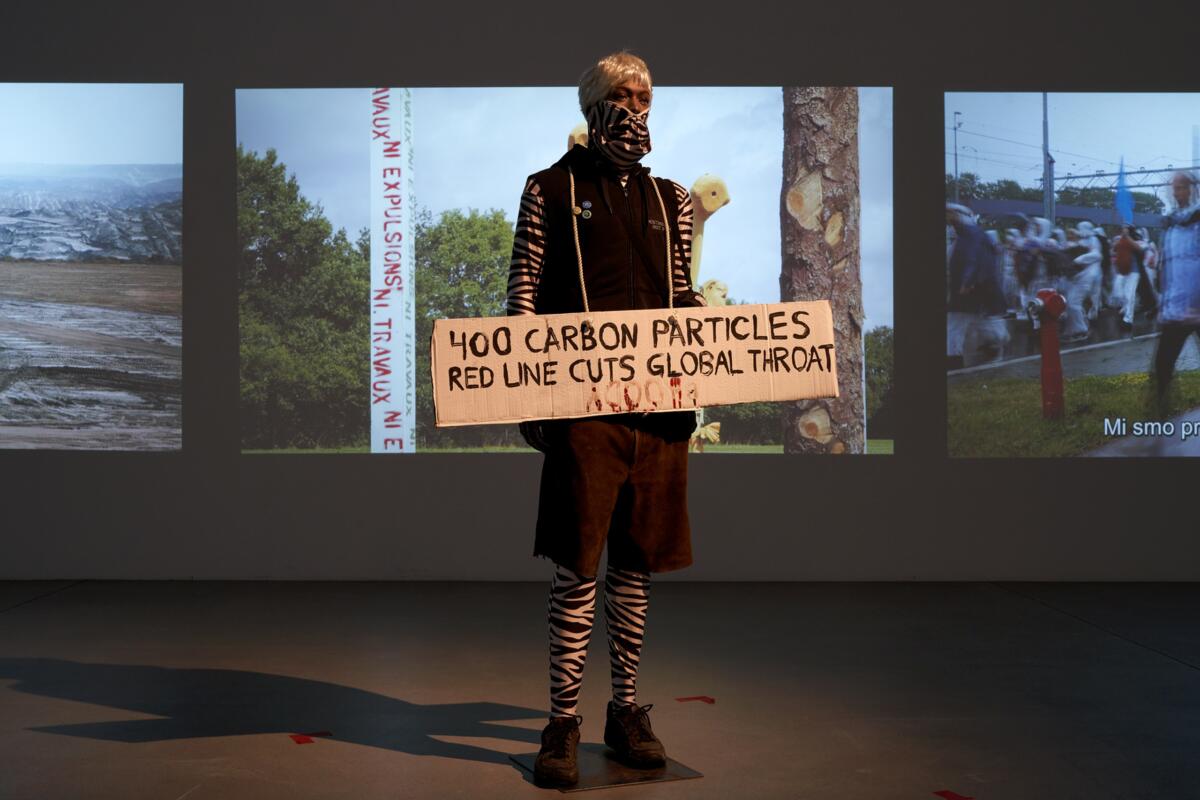

Oliver Ressler, “Barricading the Ice Sheets”, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2021. Photo: Boris Berc. Courtesy of the artist; àngels, Barcelona; The Gallery Apart, Rome

The aforementioned project was supported by the Austrian Science Fund. Can you please tell me more about the scientific side of the project?

Climate breakdown affects all dimensions of life, and the counter-movements apply many different tactics, so the research method also requires a correspondingly broad scope. My research is based on my experience in those factions of the climate movement, which act outside electoral politics and the UN framework of climate negotiations. As “global warming” is truly a global phenomenon, this research has necessarily been an international engagement. My personal connections with an international network of protagonists central to the climate movement, is an essential prerequisite for the body of work presented at MSU. My work can be seen in the genealogy of “militant research” where the researcher rejects the idea that something such as a “neutral” position exists.

The specificity of some of your videos is that you actually shoot meetings of different activists, for example climate meetings. I would call this decision “a director’s statement.” Why this statement and why is the documentary touch so important to you?

My artistic production involves the recording and documentation of assemblies and work meetings of social movements. I consider this important because through it we can experience how these central actors in the fight against climate disruption organize and act. Within the exhibition, an example for this artistic strategy, is the film Not Sinking, Swarming which is based on recordings of a preparation assembly for a blockade of a city highway in Madrid. A different strategy is applied in the 38-minute film Barricade Cultures of the Future, and the related shorter piece Overturn the Present, Barricade the Future. Both bring together protagonists of the climate justice movement who all have a background as artists. This open-ended but carefully considered approach allows us to deepen our understanding of the relation between art and climate activism, or what Nato Thompson described as “the creative and productive unity of art and activism”.

In which way do you connect to the activists when filming them, and how does the symbiosis of your art and activism manifest?

Over the years I have established a large international network of people who believe in what I am doing. I usually contact these people in order to get access to certain situations that might be inaccessible for other people, or to help connect me to other specific people.

For some time I have been personally unsure whether my artistic work relating to activism should be described as activist work or indeed whether I should be seen as a participant of these movements at all. Was I an activist by virtue of this activity, or was I rather a sympathetic observer positioned in solidarity with the object of research? I still have no definite answer to this question, partly because my practice of varying strategies between one project and the next could generate different answers in each particular case. But I have received an answer many times over from activists and movement participants when presenting and discussing my work both within an “art world” context and outside it. Social movement activists have repeatedly told me that they regard me as part of the movements because of the way I approach my work. They see my work as wholly unlike that of even the most personally sympathetic journalist, whose reporting is bound by a professional code of “neutrality” to eliminate all trace of such sympathies. Whether “neutrality” is epistemologically possible at all in politically contested matters is doubtful to say the least; what is beyond doubt is that “neutrality” or “impartiality” in hegemonic media organizations means compliance with political precepts which are held to be self-evident.

Oliver Ressler, “Barricading the Ice Sheets”, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2021. Photo: Boris Berc. Courtesy of the artist; àngels, Barcelona; The Gallery Apart, Rome

Is it possible for an artist to live what she/he preaches nowadays? How do you tackle this problem?

Usually the people driving SUVs and flying to distant holiday destinations three times per year don’t participate in the blockades of the infrastructure of fossil capitalism. But for strategic reasons I would propose we shift the discourse a bit away from personal responsibility (which of course exists) and to put our attention to where the largest parts of the emissions are being generated. Only 100 transnational corporations are responsible for 70 per cent of carbon emissions. In addition, fossil fuels are still heavily subsidized by our nation states. These are the things that need to be our most urgent targets. We need more than just different consumer behavior. In order to tackle the fossil fuel capital-driven climate emergency we need to attack the structures of this rotten system.

A lot of your oeuvre is made in the medium of film and video. Can you tell me about your process of film-making?

There isn’t a recipe for how I carry out a film. There are films that require a lot of research and fundraising before I can start to produce and there are others that require only a small amount of preparation. When I participate in mass civil disobedience actions with a small camera, with some luck, the films develop just in front of my eyes as an involved observer. In these cases, the more time-consuming work is to order and contextualize the recorded material in the editing process. For these pieces I usually film on my own. In other films, primarily when I document larger assemblies or groups of people speaking in front of the camera, I work with a group of people. Also, there are different forms of films that emerge from these recordings. Some are based solely on the spoken words of the people in front of the camera. For other films I write the narration, often in collaboration with Matthew Hyland. I have made films that are 1.5 minutes long and others that are nearly two hours long. Some films were completed in 3 months and others have taken me years. The work is much more diverse than it might appear.

Oliver Ressler, “Barricading the Ice Sheets”, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2021. Photo: Boris Berc. Courtesy of the artist; àngels, Barcelona; The Gallery Apart, Rome

Not only are you an artist but you are also a curator. How do you connect your curatorial practice with the artistic one?

I already had visibility as an artist when the first curators started asking me if I might be interested in curating shows myself. It was never my plan to do it, but it is maybe a good possibility to share the research and networks I established and to make them accessible in the format of an exhibition. I curated a section on the alter-globalization movement for the Taipei Biennale in 2008, by that time I had already carried out several films on the theme. Together with Greg Sholette I co-curated a cycle of exhibitions on the financial and economic crises, which was also the topic of several of my art works and solo exhibitions. Both my artistic and curatorial work is research-based. In certain periods I work on artistic and curatorial projects at the same time, the work overlaps and at least during the working process there does not appear to be such a big difference from a practical level. The exhibition I curated most recently just closed a few weeks ago at the Museumsquartier in Vienna, it was a show about artists who consider themselves as part of the climate justice movement. The exhibition shows a wide range of strategies and approaches to how artists become active within the movement. It is the first international exhibition to attempt something like this, and so it received a lot of attention. It will be traveling next year to Cyprus and Ecuador.

What was it like to set up the exhibition at MSU and what are your plans for the near future?

It was an amazing experience to combine, for the first time, all of the works I carried out on one theme – climate breakdown – in this large-scale exhibition. The 59 exhibited works span the period from 1994 to 2021. It was a fantastic experience to work on this with curator Leila Topic, who was very supportive throughout the year-long preparation process of the exhibition.

I am always working on several works at the same time that are in different stages of production. I am currently working on a film about Europe’s longest-lasting tree-top occupation in the Hambacher Forest (for ten years now around one to two hundred people have lived in this forest near Cologne, Germany, preventing its planned destruction by clear-cutting), for which the editing was completed only a few days ago. I handed the film off to a musician to work on the sound. I am also preparing a film for the upcoming Biennial of Casablanca, for which production has already been delayed a few times due to the pandemic. And I am following the protests and blockades against a four-lane highway plan for Vienna. This process took a major shift in the past few days as the City of Vienna instructed a lawyer to send around 50 letters to individual activists, organizations, and two traffic experts from the Technical University, in an attempt to intimidate participants in the blockades and other outspoken critics of the freeway scheme. I was one of the recipients of the intimidation letter, which of course disrupted all my plans and work commitments last week. Amnesty International Austria described these letters as a “SLAPP” lawsuit, making strategic use of the courts to discourage activists and critics. In terms of exhibitions, Barricading the Ice Sheets will be presented in various configurations of solo exhibitions at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.), Berlin; Tallinn Art Hall, Tallinn; and The Showroom, London, in 2022.

***

The interview was conducted on the occasion of the exhibition Barricading the Ice Sheets at Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb which was on view from November 30th 2021 until February 6th 2022.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Oliver Ressler |

| Exhibition | Barricading the Ice Sheets |

| Place / venue | Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb |

| Dates | 30.11.2021 - 06.02.2022 |

| Curated by | Leila Topić |

| Photos | Boris Berc |

| Website | www.msu.hr/en/ |

| Index | Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb Neva Lukic Oliver Ressler |