When in 2017 we started doing our ambitious and extensive research on the history of Belarusian photography, we knew the result would not be presented in the form of a coherent, completed and smooth narrative where periods follow one another with rational inevitability. The vision of the history of Belarusian photography as a discontinuous, discrete phenomenon had been introduced by Valery Lobko long before our research started. He emphasized there had been no single narrative, and the latter was given ex post facto, retrospectively, resulting from nostalgia for a big history, “If <…> we take into account only creative photography, there you come across very discrete, disconnected periods totally lacking any linear development. I personally believe that this whole history is the history of creative photography — and I can try to prove it — since the post-revolutionary period to the present day — it has featured completely separate and disconnected existence with frequent long breaks.”[1]

In Belarus there have been no published books on the history of Belarusian photography – neither a comprehensive encyclopedia which would fully present this phenomenon nor a crucial number of albums or analytical books on selected Belarusian photographers.[2] Nevertheless, it is safe to say that the way of speaking about Belarusian photography has been formed. That is the history of Belarusian photography has not been thoroughly documented, but there are already its unambiguous and precise outlines with different viewpoints and a general concept of the narrative of the history of Belarusian photography: the hierarchy of events has been traced, the list of main and secondary names – defined, as well as their roles. It appears that we need not so much a reflection on Belarusian photography and its history but detailed and good publications, books and albums about individual photographers, directions or significant events. Thus, for example, regarding the history of the 1970s, the reproduction of the phrase “Minsk is a photographic Mecca” often occurs in our discourse. However, this phrase itself is not problematized or subjected to detailed analysis, we do not research other geographical points where, probably, photographic events of no less importance took place.

The study of a conventional narrative of the history of Belarusian photography and its critical analysis reveal that the structure of such a narrative, the core network of concepts, the scope of significant and insignificant events are developed in two ways.

The first can be related to the inner attempts to understand one’s own place in the narrative. It refers to the construction of the history of Belarusian photography in the late 1970s–1980s, first of all, by the members of the photo club “Minsk” with Yuri Vasilyev, Yevgeny Kozyula, Valery Lobko, and later Vladimir Parfenok among them. They were not only describing contemporary photography, but were trying to understand it in the historical context.[3] Thanks to their efforts, Belarusian photography was conceptualized and got its place in a global narrative for the first time. In terms of historiography, it was a breakthrough in the understanding of Belarusian photography, but the narrative itself was not perfect due to the involvement and interest of its creators. It was not an analytical, scientific approach, but rather an approach of practitioners eager to inscribe themselves into a wider context. In such descriptions we often face the same problem: photographers keep mentioning only Minsk photography, significantly reducing the importance of communities and events that took place in other cities. The second way emerged in the late 1980s–early 1990s and was formed by an external vision. Due to the “opened borders,” creative exchanges, first between Minsk and Moscow, and later between Minsk and Scandinavia (Sweden, Denmark, Finland) came into play. Young Belarusian photographers started to participate in exhibitions and youth exchanges and, as a result, Belarusian photography drew the attention of foreign curators and art critics. Meanwhile, Belarusian photography was singled out as an autonomous school in the context of post-Soviet photography.

Thus, the Finnish art-critic Hannu Eerikainen speaks about Valery Lobko, the graduate of Studio-2 and Studio-3, as about a representative of “Minsk School of Photography”,[4] formed on the outskirts of the Soviet Union. At the same time, it is worth mentioning that this is an opinion of an external observer who was not involved into the complicated internal context. If photography was of interest to foreign curators, it was labelled as anti-soviet, political and destroying “the great soviet utopia.” The photos of Belarusian photographers (such as Vladimir Parfenok, Sergey Kozhemyakin, Valery Lobko) were published in international journals, for example, in “Foto & Video”, etc.

That is why the concept of “Minsk School of Photography” is formed from the outside. Afterwards, this concept is locally appropriated by the local field and is used to legitimize its own value. And in 2013, “ROSPHOTO” bought the archive of Belarusian photography and called it “Minsk School of Photography”,[5] which means that the concept had already been recognized as a phenomenon of Belarusian photography. However, such a way of description is also problematic, since it is formed only around Minsk and, in fact, presents a colonial narrative of Belarusian photography.

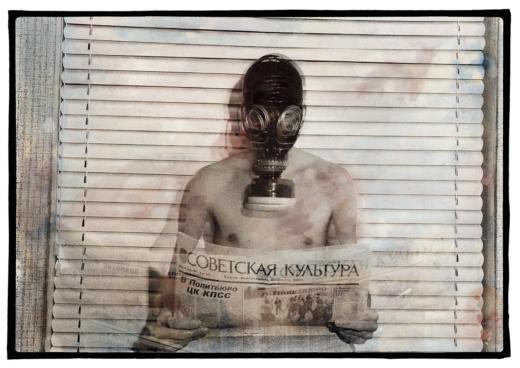

V. Parfenok, from the series ‘Persona non grata’, 1988

As researchers, we did not intend to be between Scylla and Charybdis and mediate between the self-description of the 1970–1980s and the colonial definitions of the 1980–1990s. We deliberately left the existing canons of speaking about Belarusian photography out and concentrated more on analyzing the very phenomenon of the history of Belarusian photography. The idea was not to include all the photographers in this book, but to explore the concept of “Belarusian photography” itself.

Similar to any other phenomenon, Belarusian photography is not isolated. It is included in a wider political, social, economic context and constructed within it. As Valery Lobko rightly pointed out, “Prominent authors, in fact, cannot come out of the blue — it requires conditions and potential figures.”[6] We assumed that photographers and their photographs are not the result only of inner efforts. The personalities of photographers were shaped by the time they represented and broad socio-political, economic, ideological context they lived in. Moreover, the photograph itself, perhaps, like no other medium of art, is most sensitive to technical changes and technological innovations. Therefore, instead of recounting the epochs and stages, we wondered what way we could choose to approach the history of Belarusian photography. What reasons do we have to consider these discontinuous, scattered fragments as the history of Belarusian photography? What can we do to make sure that the concept of “Belarusian photography” will not become a fixed form and turn into an ideology?

Thus, the book starts with Аlexey Bratochkin’s article and it is not specifically dedicated to Belarusian photography, but rather to the problem of how we can approach the analysis of historical material, and how this approach defines our current vision. This article serves as a peculiar prism through which we view the concept of Belarusian photography trying to avoid a non-reflective look. While refusing a linear, connected, comprehensive interpretation of the history of Belarusian photography, we introduce several entry lines that, we believe, are important and shape our vision throughout the study.

Although the lines are set in historical perspective, they are not necessarily interconnected. These 5 lines allow us to look more extensively at the history of Belarusian photography and concentrate not so much on the enumeration of significant events and facts but on the reflexive perception of the very phenomenon of “Belarusian photography.”

5 ENTRY LINES TO THE HISTORY OF BELARUSIAN PHOTOGRAPHY:

PEOPLE

This section presents the analysis of activities and the description of people who, as we see it, have contributed greatly to Belarusian photography and influenced it in two ways – infrastructurally and aesthetically.

#infrastructure_person – a person responsible for the establishment of structures and institutions influencing the development of Belarusian photography.

#another_vision – photographers who have transformed the language of the medium, changed and broadened normative understanding of photography.

Definitely, when introducing these people, we did not aim to describe them as one single school or period, however, in one way or another, their work has formed the very concept of “Belarusian photography” and made it visible. Unfortunately, the book volume has not allowed us to include all the photographers who made their mark in the history of Belarusian photography. Moreover, we have narrowed our research in order to focus on the phenomenon of Belarusian photography. We hope the results of our work will arouse more interest in photography and stimulate a further in-depth study of significant figures and movements.

EVENTS

This entry line is based on the key events and directions related to Belarusian photography at one time or another. Generally, these events are interconnected neither conceptually nor aesthetically, but, at the same time, they do not have cause-effect relationships. However, in our opinion, it was especially those events to boost the transformation, development and even the outburst of the photography movement. Their description will enable us to better understand the way a particular photography or event were inscribed in a wider context.

INCLUSION OF THE EXCLUDED

There is a central idea of our research. It was crucial for us to go beyond the limits of the accepted canons of Belarusian photography and analyze names and events which for a variety of reasons were excluded or remained on the sidelines. While analyzing a period of amateur club photography, the necessity of such a technique became especially evident – the results of this study were presented at the exhibition “59/82. Belarusian photography open data” during the festival “The Month of Photography in Minsk” (2018). The search for forgotten or excluded names, events, movements, most commonly, was conducted in two directions — geographical and gender. Due to various circumstances, the way of talking about Belarusian photography can be viewed as men- and Minsk-centric. Therefore, now we are paying greater attention to the analysis of names and events taken place in the Belarusian regions. This approach was especially important for the period of the amateur club photography, when Grodno, Mogilev and Gomel, along with Minsk, played a significant role in it. The gender perspective has also proven to be the key one for the analysis of Belarusian photography. While applying the gender-sensitive perspective, we were able to find out those important female names that had remained on the margins of history, for example, those of Valeria Barkhatova, Irina Sukhy, Svetlana Balashova, Nataliya Dorosh and others. We also tried to explain why Belarusian photography lacked female names and how the excluding processes were evolving. The results of this study have been presented in Anna Karpenko’s research article “Woman with a camera”.

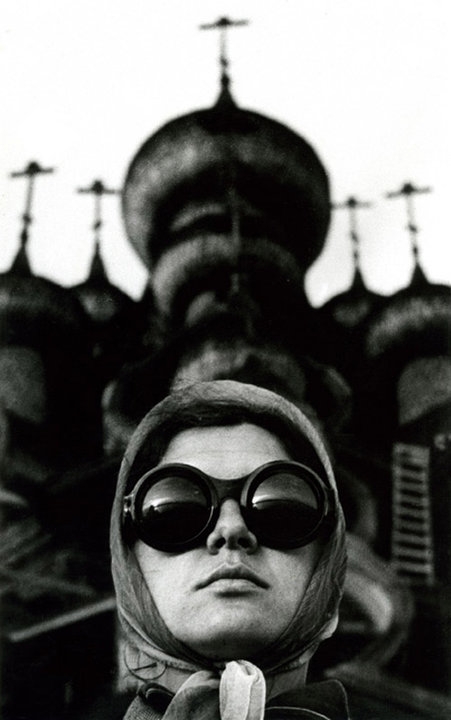

Y. Vasilyev, from the series ‘Kizhi’, 1971

COMMUNITIES AND ASSOCIATIONS

Photography is not an isolated phenomenon, and it usually develops along with the establishment of a sustainable infrastructure. The latter requires a photography community – like-minded people identifying themselves as such. The study of the emergence of such communities, the establishment of infrastructure around them and the search for a new language of the medium is also one of the key points of this book. Thus, the idea of community and association, which is repeatedly articulated throughout the history of Belarusian photography, is the main axis of our research. These kinds of communities and associations were found in the period of the 1920s – at that time, promoting the development of avant-garde photography. The rise of the amateur movement was also connected with the foundation of the first Belarusian photo club in 1960 that made photography open to the public. The establishment of educational studios in the 1980s and training of young photographers led to the emergence of an entire movement known as the “new wave of Belarusian photography.” The given examples demonstrate how important it is not to interpret Belarusian photography based on individual photographers’ efforts, but to view it as a whole considering the establishment of certain structures and associations as a significant factor for the formations of key personalia of Belarusian photography.

In terms of this strategy, it seemed important for us to show why these communities and associations become catalysts for transformation and development of Belarusian photography, on the one hand, and – on the other hand – to analyze the reasons why they keep on disintegrating, failing to create stable and long-term institutions like a photography museum or an academy. Olga Bubich has reflected on this topic in her article.

PHOTOGRAPHY ANALYSIS

There is a constituent part of this book and it is aimed at semiotic interpretation of images. Photography, as mentioned above, is closely connected with some political, social, business or ideological context. The context, in turn, influences the role photography plays in society and the form it takes. This interconnection is clearly traced through the documentary and club photography of the 1960s. The difference between the media and the statuses of these two photography types shaped not only different styles, but also objects and themes of photography. Documentary photographs were printed in newspapers and journals reflecting the official ideology and position. Its vision correlated with Soviet government pathos and illustrated the five-year plans achievements. Among the topics photographers chose themselves, there were usually large construction projects, specific cityscapes, portraits of important political and cultural figures and top performers. The photos of everyday scenes were usually staged and noticeably retouched. Amateur, not professional photography was marginal in its functioning and free to choose themes and means of expression. Therefore, amateur photographs of the 1960s capture a lot of everyday, insignificant scenes, in comparison with staged portraits, such as the city bustle, nature, etc. In a nutshell, photography is affected by broader contexts, that is why we wanted to give the reader the keys to understanding and deciphering these contexts, and also to show how the latter shape the image. Semiotic analysis is vital because it provides us with an opportunity to see and analyze the photograph itself. Therefore, in addition to individual photographs analysis, the book presents Olga Shparaga’s article where the way different photographs fit into history and become canonical, or at least significant, is described.

This approach allows us not just view photographs as “good/ bad”, “excellent/poor”, “captivating/unpleasant”, but also find other ways of interpretation, implying the search for answers to the questions about how images were taken or what context influenced them, etc.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that to make this book, we have invited not only experts in the field of photography, but also researchers, philosophers and historians who are not directly associated with the media – although, generally, articles on particular people or events were written by field-related experts. For example, articles on people and events of the photography of the period prior to the 1920s were written by Nadezhda Savchenko, one of the eminent researchers in this sphere. The history of the amateur club movement was described by Darya Amelkovich. And we have turned to Olga Bubich for the analysis of contemporary photography.

We have also brought in researchers who represent a wider context: for example, an article about the “Nova” Gallery was written by Vitaly Shutsky; a researcher and art critic Tania Arcimovich prepared an article about the group “Belarusian Climate”; a curator and art manager Sophia Sadovskaya made an article about Irina Sukhy. The section “Analytics” contains the research pieces of Alexey Bratochkin, Olga Shparaga, Aleksei Borisionok, Anna Karpenko, Olga Bubich and Nadezhda Savchenko.

Such a multidisciplinary team of this book has enabled us to explore Belarusian photography from different perspectives, analyze various contexts that have a great influence on it and go beyond a traditional way of talking about it.

The text first appeared in the book The history of Belarusian photography, ed. Hanna Samarskaya, Antonina Stebur. – Biruliškės, Kauno r. : Kopa, 2020.

[1] V. Lobko. The history of Belarusian photography. A talk with Irina Bigda. – Hanna Samarskaya’s personal archive, 2008

[2] Although there are several initiatives dedicated to the publication of individual albums and the periods of the history of Belarusian photography. For example, “pARTisan” albums series includes a few issues dedicated to photographers (I. Savchenko, S. Zhdanovich), since 2017 the collection of albums of Belarusian photographers has been published by “The Month of Photography in Minsk”.

[3] Yuri Vasilyev’s article “From the history of photography in Belarus. Traditions and trends of development” can be named as the quintessence of this approach (from the collection of articles of the International Scientific and Practical Conference “Photography in the art space” (Minsk, Belarusian State Academy of Arts, 2008).

[4] Т. Еskola & Н. Ееrikajnen. Toisinnakijat. SN-Kirjat, Helsinki, 1989.

[5] In 2014 the exhibition “Minsk School of Photography. The 1960s-2000s” was held by “ROSPHOTO”.

[6] V. Lobko. Meetings the legends [znyata.com] – Access: http://forum.znyata.com Viewed 23.06.2019

Imprint

| Author | Hanna Samarskaya, Antonina Stebur |

| Title | The history of Belarusian photography |

| Index | Aleksei Borisionok Alexey Bratochkin Anna Karpenko Antonina Stebur Darya Amelkovich Hanna Samarskaya Irina Sukhy Nadezhda Savchenko Nataliya Dorosh Olga Bubich Olga Shparaga Sergey Kozhemyakin Sophia Sadovskaya Svetlana Balashova Tania Arcimovich Valeria Barkhatova Valery Lobko Vitaly Shutsky Vladimir Parfenok Yevgeny Kozyula Yuri Vasilyev Аlexey Bratochkin |