The world we live in is changing. Scientific findings about the global warming of Earth’s climate, collected for dozens of years, are now joined by our immediate experience with unprecedented weather fluctuations here in Europe, which are no longer the subject of traditional polite conversations, rather becoming a disturbing topic for society-wide discussion. We fear extremes like torrential rain, floods, heat waves and drought. Water, the key factor for the existence of life on Earth, plays a crucial role in all these questions. However, the transformations of global systems consist not only in the now undeniable global warming (which is currently advancing at critical speed) but are fundamentally related to the rapid decrease in biodiversity (i.e. the massive disappearance of species) and unprecedented chemical-physical processes contributing to the overall pollution of ecosystems. All these interrelated processes are strongly stimulated by human activities and the current development is provably heading to a collapse that is most likely to endanger the very existence of human civilization.

While the Interconnection: Bodies of Water exhibition is loosely based on the knowledge of these facts, it does not aim to deepen environmental anxiety and grief, nor does it strive to preachingly wag a warning finger or immediately document the manifestations of the environmental crisis we are facing today. Our approach is rather subtle, loosely drawing on the ideas of ecofeminism and hydrofeminism, as currently developed by Astrida Neimanis, Australian theorist and researcher at Sydney Environment Institute, and author of the book Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (2017). The main axis of the exhibition is the idea of interconnectedness, with water serving as a metaphor for this interconnection. As Neimanis reminds us: water, which constitutes approximately 80% of our body, its proportion being even higher in a number of animal and plant species, links us to all organic and inorganic things on this planet in a constant cycle, going in and out, blurring boundaries. As if every living species, every cell was an island in an endless sea which inevitably connects us all. While this connection is factual-material, it also generates a basis for a specific notion of subjectivity. Neimanis, whose thinking falls within the broader current of today‘s posthumanism, accentuates literal fluidity, the fluidity of the individual. Flowing – into me, in me, through me – means becoming.

From this holistic perspective, we are never separate from each other. As John Donne poetically put it: “No man is an island (…) Therefore, send not to know for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for thee.” However, in the concept of hydrofeminism, there is a mutual connection not only between people but also between other “bodies of water” including other organisms, rivers as well as global circulation systems. As Neimanis observes, while the total quantity of water on the planet is essentially constant, what changes is its distribution and quality; along with the quality of life. Water as such may still be here for thousands or millions of years. However, how long will our bodies be among the bodies of water?

Through visually outstanding and yet very distinct artworks, the Interconnection exhibition focuses on the motif of water as a condition of life, on the motif of the circulation, flow and merging of life forms, and figuratively on the search for an extra-human perspective which sees the human as a part of life rather than the highest life form in our ecosystem.

…

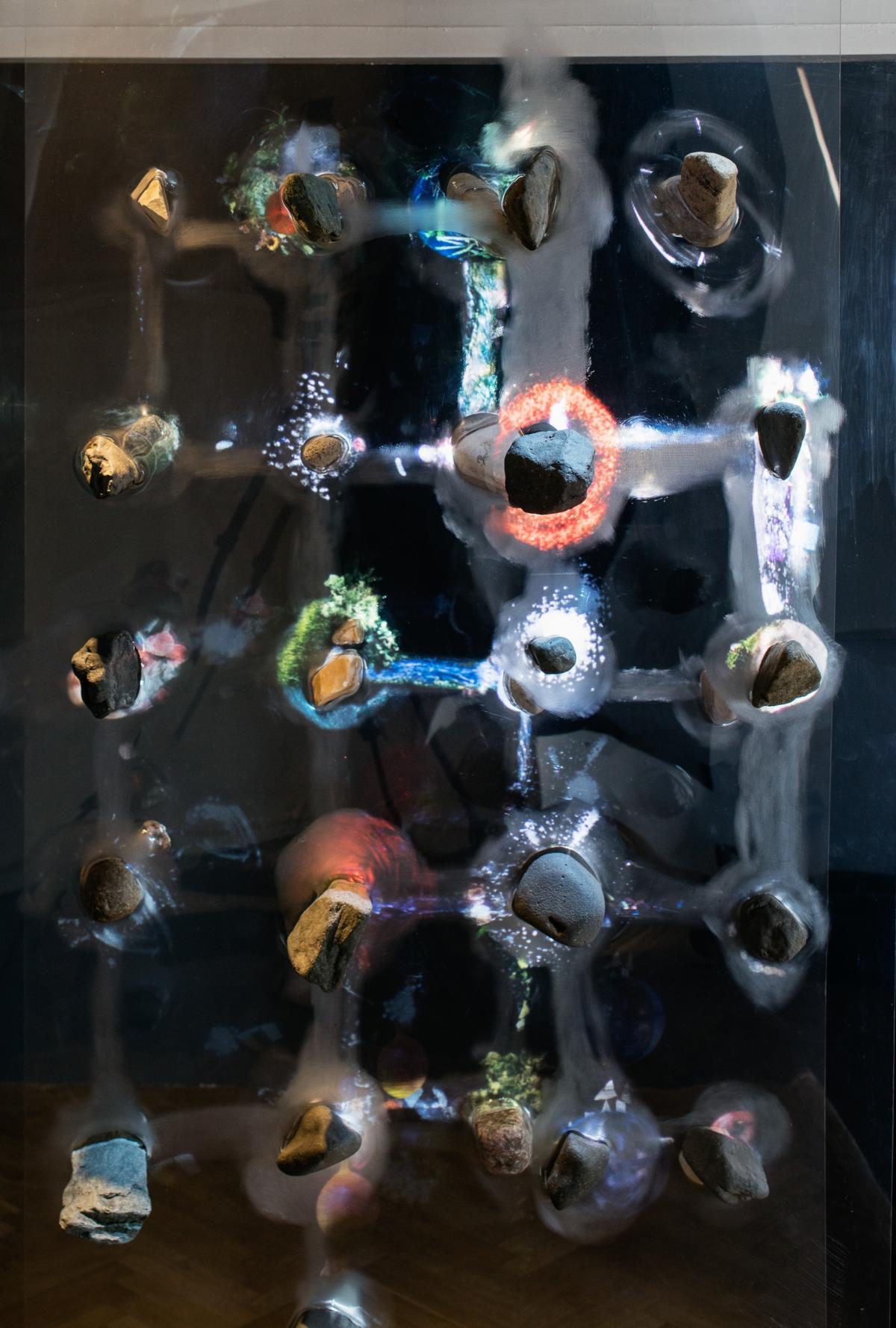

The technologically sophisticated and precisely rendered multimedia installations by Jakub Nepraš represent complex universes whose richness makes it almost impossible to be fully grasped by the viewers. Thus, they are an impressive metaphor of the complexity and interconnectedness of our own environment where separating nature and culture no longer makes sense. The video-sculpture entitled Meadow (2012) depicts the abstracted flows and exchanges between individual “nodal points” embodied by stones. Their configuration may remind of the schemes of chemical or molecular systems. Each stone represents a certain transformer recreating symbolical values and sending them to its neighbor in modified form. In the front lucite layer of the relief, transitory impulses circulate among the stones, having no lasting value for the community. The rear layer, on the other hand, shows more meaningful relationships reflecting the vitality and potential for the further development and life of the system. The stones on the meadow pass the baton, shouting each other down like crickets in the grass or birds in the treetops.

Universal interconnection is literally illustrated by Valko Chobanov’s painting A Beautiful View (2018), though through completely different aesthetic means. Rendered in cartoon style, the joyful natural scene translates the message of the exhibition into a language comprehensible even to a child in a disarming manner. A little girl and her colourful friend are not alone at the lake – upon a closer look, we can see more beings – the trees and the stones, even the sandy beach and the sky have a life of their own. It is a playful depiction of the animistic belief that both living and non-living entities, or even places, have a soul.

Pavel Sterec’s video essay Vital Syndicates (2016) created in collaboration with Tereza Stöckelová takes us to the world of medicine and biology through the speeches of several scientists. Discussions on parasites demonstrate the substantially collective nature of life. Our bodies are inhabited, or rather co-created, by millions of other organisms and the majority of genetic material which can be identified on the surface and inside “our” bodies actually belongs to someone else. However, as a matter of fact, we cannot live without these “others”. From a rather different perspective, we get back to hydrofeminism’s concept of the merging of various entities whose individual identity is always in a multiway relation with its surroundings; in a certain sense, the duality of me-my surroundings no longer plays a role.

Johana Střížková’s installation Colony SP03 (2018/2019) can be seen as a counterpart of Sterec’s video. In a three-hundred-liter aquarium, we can observe the symbiotic culture of vinegar bacteria and several types of yeast known as kombucha. It lives off the solution of sweet tea and becomes gradually fermented, producing a characteristic beverage popular in holistic medicine among others. The exhibition visitors can help themselves to the drink. While the main part of the kombucha colony can be seen growing on the surface, it permeates the whole solution like invisible mycelium. When drinking kombucha, we literally absorb the probiotic culture which then takes effect on our digestive system.

In her interdisciplinary work, often including natural elements like stones and corals, Nona Inescu explores the interaction between humans and other animal and plant species with which we share our living space. In her installations and photographs capturing the contact of the human body or man-made artificial materials with inanimate objects of natural origin, non-human bodies, we can feel the tension between the organic and the inorganic. Her work raises the disturbing question of what is really alive among the depicted objects and what was severed from our shared natural substance. Through the installation arrangement reminiscent of a display of luxury commodities such as jewelry or a tasteful showroom of exclusive nutritional supplements promising eternal youth, the artist directs the viewers‘ attention to the petrified coral from the Miocene epoch when the planet was still unaware of the danger it would face one day due to one of the animal species which was yet to evolve. The view of this object, an animal, a plant and a stone in one which is dozens of millions of years old, gives but a faint memory of the time when human existence as we know it today – unlike many other organisms we now tend to see as subordinate to us – was not a thing at all.

The abstract, dreamy watercolors of Karolína Rossí seem to literally embody the water element in its variability and multiformity. The splotches and blurred outlines of organic shapes, splattered around the entire gallery space, remind of water surfaces, water animals or even cells and primordial life forms with their changing shades of blue, green and grey. Thus, the metaphor of a drop of water and the living organism literally gains visible outlines here. Despite being depicted in static two-dimensional paintings, water retains its liquidity in Rossí’s paper collages.

What would a fish song sound like if these silent animals could express themselves through singing, and what would they sing about? Catherine Biocca‘s anthropomorphic installation Marine IV (2019), where a fish is not only singing but also simulating the gallery visitors admiring the displayed artworks, brings an unexpected connotation in relation to the real visitors. The cute fish voice sings about essentially human experiences that cannot be experienced by fish – cheerful conversations and beautiful beach walks, addressing the present visitors by conversation questions as its equal. The notion of togetherness and interspecies equality, crucial for hydrofeminism, is unexpectedly and amusingly put into practice, and it is upon the viewers to realize how they feel in this newly established relationship.

The fragile installations of Maria Nalbantova, continuing her solo exhibition Weather Forecast (2018), are a lyrical stylization of the natural processes that transcend us. They are “bodies of water” on a macroscopic scale: hydro-geological processes and manifestations of weather and climate. The assemblage entitled Disaster depicts the events leading to flash floods, experienced by the artist herself, in a nutshell. The blurred drawing from the artist’s sketchbook – a product of invention and chance at the same time – became a by-product of the floods. The object Red Rain alludes to “blood rain”, a phenomenon reappearing in India, Sri Lanka and South Europe among others. The red hue of the rain is probably caused by the spores of a certain type of algae surviving in the air; however, there were also hypotheses claiming that the phenomenon is of extraterrestrial origin, proving the existence of life in the universe. In any case, water – in the form of rain – is again seen as a mediator between different spheres.

Tabita Rezaire’s video Deep Down Tidal (2017) approaches flows and interconnection from yet another angle. In her proclamative essay, the artist, who has dealt with post-colonial criticism and the rehabilitation of non-western knowledge and spirituality on a long-term basis, addresses the oppressive nature of the Internet whose transmission is materialized in a network of submarine cables repeating the trajectories of colonial powers, especially the slave trade. Thus, the water environment plays the role of a mediator here as well. However, in the second part of the video, the artist thematizes water as a vital element whose distribution is (similarly to data and information) unequal, telling of global social differences. Thus, she brings us to a stance which is also present in hydrofeminism: water, like other common possessions, needs to be shared and taken care of. She brings us back from the all-embracing planetary interconnection to particular environmental, economic and primarily political questions.

The ambiguous figure of The Ferryman (1996/2019) with human and animal attributes, sitting in a motionless kayak on the non-existent surface of an empty pool, combines a number of moments accentuated individually in the other works of the exhibition Interconnection. The poetic and playful language of Petr Nikl gave rise to a sculpture that may make us smile at first glance, however, after longer observation, it may easily make a depressing impression instead. Its face, as if hidden behind an expressionless mask, may stir a sense of empathy on the one hand – when we become fully aware of its loneliness, both literal as it is situated outside the inner gallery space, and figural due to the obvious non-belonging of this being which has no place either in the human or in the animal world. However, at the same time, The Ferryman can also be seen as a sinister harbinger about to take us to the future. What will it be like with respect to the advancing depletion and contamination of water? So far, the answer to this question still lies at least partially in our hands.

…

The Interconnection: On Bodies of Water exhibition is the second output of the long-term project Islands: Possibilities of Togetherness launched in 2019 by Jindřich Chalupecký Society, a platform for Czech art in international context. Bringing together a number of partner organizations from various countries, the project addresses the coexistence and mutual relations and ties between individuals and collectives on a general level. The Interconnection exhibition at the Swimming Pool gallery wants to bring attention to the level of coexistence and collectivity that is broader than the human one. Therefore, the exhibition takes a planetary, interspecies perspective which will run through the entire Islands project in themes like sustainability, ecology, utopia vs. dystopia, ethics, communication and symbiosis.

Imprint

| Artist | Catherine Biocca, Valko Chobanov, Nona Inescu, Maria Nalbantova, Jakub Nepraš, Petr Nikl, Tabita Rezaire, Karolína Rossi, Pavel Sterec, Johana Střížková |

| Exhibition | Interconnection: On Bodies of Water |

| Place / venue | Swimming Pool, Sofia |

| Dates | 28 July – 4 August 2019 |

| Curated by | Veronika Čechová, Tereza Jindrová |

| Photos | Tomáš Souček |

| Website | swimmingpoolprojects.org |

| Index | Catherine Biocca Jakub Nepraš Johana Střížková Karolína Rossi Maria Nalbantova Nona Inescu Pavel Sterec Petr Nikl Swimming Pool Tabita Rezaire Tereza Jindrová Valko Chobanov Veronika Čechová |