When I was 5 years old, I began to think about death. Later, in my teens, thoughts about non-existence went beyond a simple childish interest, they almost uncontrollably captured the space of my feelings. At any given moment, especially before going to bed, I could be suddenly seized by some very special existential yearnings. The fear of death and the passage of time washed over me with particular force during my trips to Minsk, where I went mainly to watch theatrical performances. I remember Minsk from my childhood like this: red velvet and plaster mouldings of the Stalinist Empire style, wide avenues and an almost physical feeling of the inevitability of death. Many years passed before I found an explanation for my childhood sentiments, and so thanks to words and various cultural images, the feelings subsided. Benjamin Cope, a researcher of Eastern European urban spaces, described Minsk as a city engulfed by the ghost of Marx – manifesting as visual signs of a bygone era in the form of monuments, bas-reliefs, street names that have lost their meaning in contemporary capitalist reality, and which, nevertheless, cannot be overlooked in the space of Belarusian cities[1]. Perhaps it was living among the specters of socialism and the Second World War that led my childish imagination to intense reflections about the transience of human life and to some uncanny melancholy. At the exhibition When The Sun Is Low, The Shadows Are Long at Galeria Arsenał in Białystok, the familiar, but distant feeling of the proximity to nothingness again made itself present. It was a disturbing and a bit pleasant flashback, like a return to something close, but long forgotten.

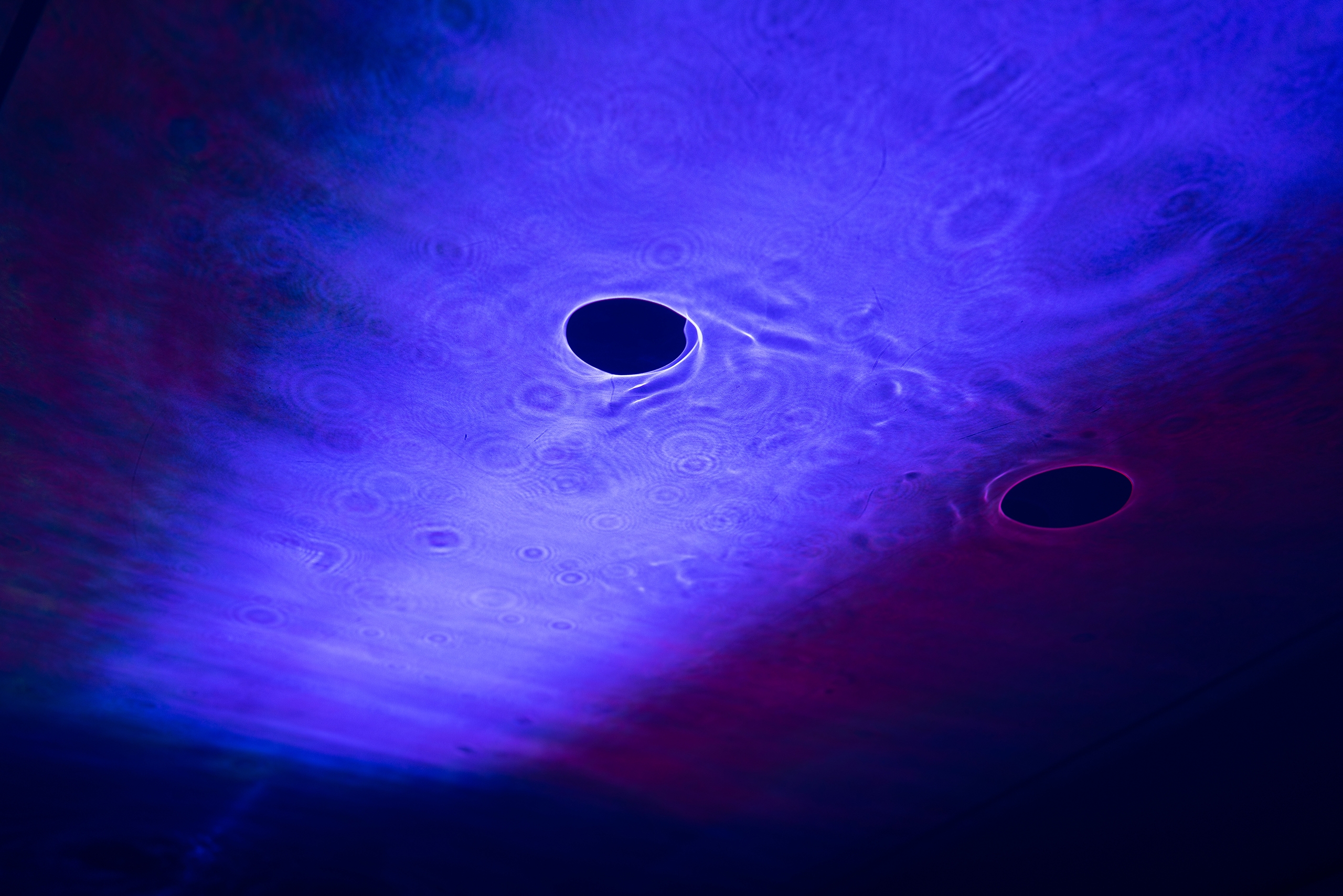

Perhaps the creation of an inexplicably unsettling atmosphere was a deliberate curatorial gesture. Trying to define “the space named Belarus, which is crumbling into many identities[2]”, the curator of the exhibition, Anna Karpenko, has collected a number of works illustrating its various sides. One of the key themes was the fascination of artists with outer space, and its visualizations, creating a sense of transcendence. Thus, the starting point of the exhibition is the iconic work “The Evil Spirits” by Jazep Drazdovič, an artist, poet, and philosopher of the first half of the 20th century who famously authored his own unique, and amateur, theory of cosmology. The kinetic installation “ER=EPR” by Evelina Domnitch and Dmitry Gelfand shows the gravitational waves discovered in 2016 by researchers from LIGO laboratory, which appeared when two black holes collided in space. In her video performance “VOID”, Irina Anufrieva directly connects the concepts of emptiness and suffering. In the words of the curator, “VOID is a place of dance, wherein muteness is the only possible language of resisting death.[3]” The dancer’s body performs the non-material pain that remains in the memory of a person who has suffered physical violence. Unfortunately, violence and torture carried out in Belarusian prisons are an integral symbol of today’s Belarus, and the trauma caused by these atrocious acts lives in the minds of all Belarusians, even those who have not experienced it personally. The fortitude, endurance, and at the same time cosmic flight of mind illustrated by the works mentioned above reminded me of the Kantian starry sky above and the moral law within. The 2020 Belarusian protests are remembered for images of people taking off their shoes to stand on benches in the crowd or stories of protesters building barricades and then cleaning up the streets. The protests were peaceful despite the blatant violence instigated by the authorities. Combining the metaphors of resilience in the face of pain and openness to the unknown (future, present, past – all these three dimensions are invariably disturbed under authoritarianism) served as an illustration of one of the sides of the Belarusian identity.

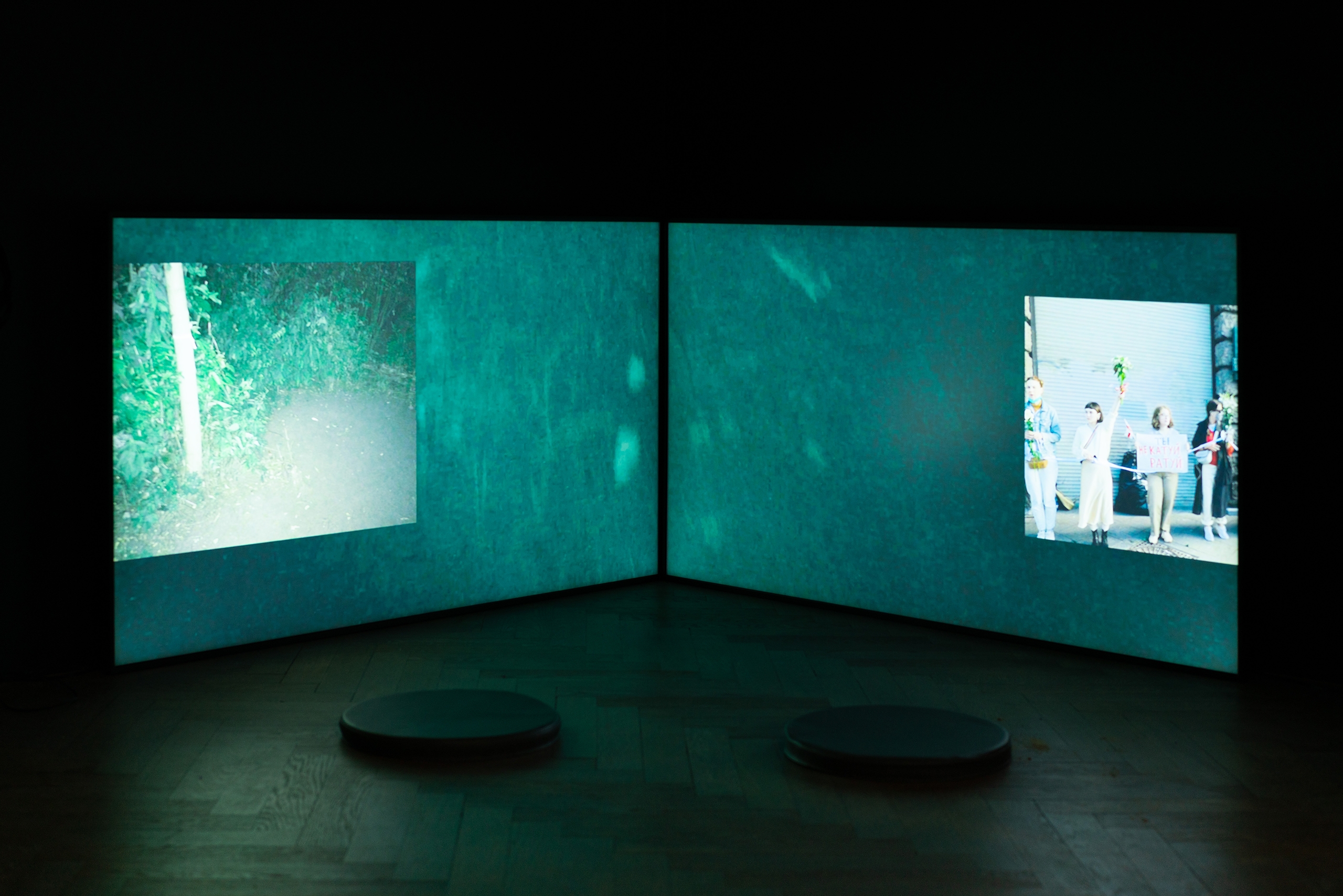

The choice of the works presented in the exhibition was also determined by the curator’s interest in the concept of borderland ethics, described by the Belarusian philosopher Ihar Babkou. In his opinion, “The borderland extends on both sides of the border, and its topological status is paradoxical: the borderland acquires a certain integrity through the fact of its own separation, i.e. through the dynamic event of separation, meeting and transition of Own and Foreign, or One and Other”[4]. In the video “Borders and Time. The Uncertainty of Borders”, Jan Helda documented the crossing of the Polish-Belarusian border along the Augustów Canal, in a place where this can only be done by driving a boat or kayak. The work speaks to the conventionality of borders of states and, at the same time, their enormous influence on the inhabitants of the border areas. Zhanna Gladko also crossed a certain border in the water. Overcoming her many years of bathophobia (fear of depths), on the day of the winter solstice 2020, the artist dived into the Baltic Sea, which became for her a symbol of a ritual connection with the element of water. Video documentation of this process was presented at the exhibition along with an installation in the form of a starry sky in the work “Reality Will Manifest On Its Own”. In both works, the border is read not only as a physical site, but also as a metaphor for the liminal. The border separates not only geopolitical subjects, but this world from another: for example, in folk Orthodox beliefs, the frontier between worlds must be crossed on a boat driven by the Archangel Michael or the Apostle Peter. The space “between” has a special meaning for Central and Eastern European post-colonial theory. Maria Todorova notes that the countries of Central Europe and the Balkans are often described as being located “between West and East”, with “East” being a relative concept[5]. At the same time, that “being in between” is often interpreted by outside (mostly Western) observers in a negative way.

Jura Shust, Evergreen, 2022

double-glazed unit, metal, wood, resin, glass, paper,

matches, digital video, 3’30” (looped)

Karpenko tried to emphasize the positive meaning of the borderland as a place that accepts ambiguity, that mixes categories and concepts. It is difficult to disagree with the fact that the historical peculiarity of Belarus as a place located between the Western and Eastern empires finds reflection in identities of contemporary Belarusians. However, taking the concept of the borderline beyond time and history can be dangerous: it can lead to a conviction that the state of being “in between” is a natural and integral feature of the territory of Belarus (which opens the possibility of questioning the sovereignty of the state). Analyzing the Belarusian identity, it is important to remember that every historical moment brings people unique experiences, visual examples of which would be interesting to consider. Unfortunately the exhibition only strongly refers to the timeless ideas associated with the space of the border. The weakness of this approach could clearly be seen in the installation “Evergreen” by Jura Shust, where fragments of a massive tree, illustrating an ancient Belarusian forest, which in local myths and legends is a portal to the other world, were connected with pictures of refugees arriving in the border area between Belarus and Poland. It felt as if these tragedies are something natural for this forest, as if the death of refugees is a specificity of the forest and not in fact the result of the atrocious actions of Lukashenko and Putin, the dictators who have implemented this plan as a way to “intimidate” EU countries. The neighboring kinetic work by Anna Sokolova, which created a spectacular illusion of never ending movement through abstract black and white shapes, only intensified this feeling of the timelessness of this situation.

Karolina Plinta, in her review for SZUM Magazine, referred to Karpenko’s curatorial strategy as escapism[6]. In her evaluation of the survival strategies presented in the works of some artists, she even saw a warning meant for Poles, demonstrating what happens when people’s freedom is taken away from them. She based this assessment on the work of “A Diary of Breath. The Mimicry of Lungs” by Olga Sazykina, who counts the rhythm of her breath and transfers it to paper. I would say this gesture means something different for the artist: it is about courage of being and manifesting her presence as something valuable. After all, Sazykina’s work also contains a story about the importance of artistic practice as a way to research and depict human existence in different conditions, which is not so obvious in today’s capitalistic digital reality which reveals all the weaknesses of the western art field.

To understand the peculiarity of the point of view from Belarus (through Belarusian optics), one must clearly understand the context, or have a special sensitivity. In my opinion, Karpenko, having chosen quite successful works to illustrate Belarusian identity, failed to contextualize them. Without understanding the context, many works can seem quite secondary in their form and in their references to conceptualism. However, the same logic that Piotr Piotrowski described in regards to the Eastern European avant-garde works here. According to Piotrowski, this avant-garde cannot be evaluated within the categories developed in the West. If abstraction in the West referred to formal questions, abstract art in f.ex. the Polish People’s Republic was first and foremost a form of protest and confrontation with the dominant Soviet iconography, and thus it is impossible to compare one-to-one works coming from different contexts, using commonly known criteria of evaluation, since they have a different artistic, social and political meanings[7].

So how could the works be better contextualized? For example, by showing how artists are accustomed to working in Belarus. In my recent conversation with artist Lesia Pcholka, she mentioned that the difference in the functioning of artists in Poland and Belarus is that in Poland, institutions perform a supportive function for artists, providing infrastructure, organizational assistance, etc. In Belarus, however, in order to become an artist, you first need to learn how to become that institution for yourself. The practice of Siarhiej Leskiec serves as a great example in this context. Leskiec, who – for a decade – has been documenting the tradition of healing with whispers and the whisperers themselves. This archaic phenomenon of the Belarusian woodlands survived Christianity and Soviet times but is disappearing now. The photographer performs the duties of a whole scientific or ethnographic team. He records what will soon probably become completely inaccessible, and if it were not for him, would be consigned to oblivion. Unfortunately, Leskiec’s entire project was represented in the exhibition by one single photograph, which makes it nearly impossible to understand the significance of his work without prior knowledge. Conversely, there was an apt decision to create a decolonial context by showing Władysław Strzemiński’s book “Theory of Vision” next to the painting of Zahar Kudin, who suffered from glaucoma and developed his own method of work which he called “Neuro-art”. Both artists shared the experience of living under extremely hard political circumstances and despite this, were able to develop highly meaningful ideas for the canon of abstract art.

Karpenko tried to change how Belarus is usually perceived from the outside perspective: as an extremely sad, almost “nowhere” place, by showing interesting sides of local identity, the strength that is hidden in small, monotonous gestures, and the hybridity of meanings. The work “Shared Secret” by Aliona Pazdniakova is dedicated to the popular children’s game of secrets, where children place various objects, considered by them as beautiful and meaningful, under glass in a hole dug in the ground. Later, the glass is covered with sand and the “secrets” are shown only to trusted friends. The artist included in the video different people from different contexts, and asked them if they had some secrets of their own. Of course, most of them said that they didn’t have anything to hide, but Pazdniakova rather highlights the fact that hiding secrets and verifying the dependability of others is something learned at a very young age by children of Soviet and post-Soviet countries. In my childhood, the game of secrets had an additional aspect that was not shown in the video: different children’s groups hunted each other’s secrets, and when they would find them, they would destroy them. It was especially important to keep the “secret” safe, and there were a lot of different ways to take care of them. The skills developed in childhood by Belarusians born up until the 90s are practiced to this day, including the will to invent new ways of partisan protest both offline and online. The desire to struggle for freedom of expression was also reflected in the work “Mandrake Gardens” by Sergey Shabohin who compared the differing definitions and manifestations of illegal gatherings in the parks in Minsk and Berlin. The work “Sew on Your Own” by Ala Savashevich recalled outdated Soviet practices in the Belarusian education system that have caused a lot of trauma in people. Alexander Adamov’s game of tag was a good illustration of the impossibility of grasping together in one clear picture an identity, which is based on so many contradictions.

When the Sun is Low – the Shadows Are Long touched upon many interesting and important topics related to the Belarusian identity, past and present. However, while the core works were focused on mysticism and transcendence, and were well connected, the other works focusing on different important issues were scattered, placed in corners, and did not resonate with each other in meaningful ways. I deliberately did not start this text with the most important question: does it make sense to organize exhibitions of artists united, first of all, by their national identity? I appreciate the fact that Anna Karpenko tried to explain such a need by setting a very specific topic, concerning the identity of people united by the experience of being born in or continuing to live in the territory of Belarus. The task was ambitious, especially because of the fact that the Belarusian question is constantly marginalized in foreign political and cultural discourse, but the exhibition itself showed that generalization does not serve the representation of complex ideas well.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1] Бенджамин Коуп

ПРИЗРАКИ МАРКСА:БРОДЯ ПО МИНСКУ ПО СЛЕДУ ДЕРРИДА, in: Белорусский формат: невидимая реальностьб Eвропейский Гуманитарный Университет, Вильнюс 2008

[2] Адвечны шлях, лодка, у якой мы плывём: Ганна Карпенка пра выставу ў беластоцкім Арсенале і беларускім пражыванні свабоды: https://reform.news/306205-advechny-shljah-lodka-u-jakoj-my-plyvjom-ganna-karpenka-pra-vystavu-belastockim-arsenale-i-belaruskim-prazhyvanni-svabody

[3] When The Sun Is Low – The Shadows Are Long, exhibition guide

[4] Ігар Бабкоў, ЭТЫКА ПАМЕЖЖА: ТРАНСКУЛЬТУРНАСЬЦЬ ЯК БЕЛАРУСКІ ДОСЬВЕД, https://knihi.com/storage/frahmenty/6babkow2.htm

[5] Maria Todorova, Bałkany wyobrażone, Wydawnictwo Czarne, Wołowiec 2008

[6] Karolina Plinta, Walka o oddech. „Gdy słońce jest nisko – cienie są długie” w Galerii Arsenał w Białymstoku, Magazyn SZUM: https://magazynszum.pl/walka-o-oddech-gdy-slonce-jest-nisko-cienie-sa-dlugie-w-galerii-arsenal-w-bialymstoku/

[7] Piotr Piotrowski, Awangarda w cieniu Jałty. Sztuka w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej w latach 1945-1989, Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, Poznań 2005

Imprint

| Artist | Alexander Adamov, Irina Anufrieva, Bazinato, Evelina Domnitch / Dmitry Gelfand, Jazep Drazdovič, Zhanna Gladko, Jan Helda , Siarhei Hudzilin, Zahar Kudin, Siarhiej Leskiec, Masha Maroz, Aliona Pazdniakova, Anton Sarokin, Ala Savashevich, Olga Sazykina, Sergey Shabohin, Jura Shust, Anna Sokolova, Władysław Strzemiński, Masha Svyatogor |

| Exhibition | When The Sun is Low - The Shadows are Long |

| Place / venue | Arsenał Gallery in Białystok |

| Dates | 01.04.2022 - 13.05.2022 |

| Curated by | Anna Karpenko |

| Index | Ala Savashevich Alexander Adamov Aliona Pazdniakova Anna Karpenko Anna Sokolova Anton Sarokin Arsenal Gallery in Białystok Bazinato Evelina Domnitch / Dmitry Gelfand Irina Anufrieva Jan Helda Jazep Drazdovič Jura Shust Masha Maroz Olga Sazykina Sergey Shabohin Siarhei Hudzilin Siarhiej Leskiec Vera Zalutskaya Władysław Strzemiński Zahar Kudin Zhanna Gladko |