If I had the strength I would publish all of my works that I consider interesting, but that’s not possible.

– Edward Hartwig[1]

The work of Edward Hartwig—fascinating, rich, multifaceted, fitting into successive streams but also original—ensures him a special position in the history of Polish photography. His impressive, over seventy years of artistic activity can be counted in tens of thousands of negatives and prints, hundreds of exhibitions and press articles, but also dozens of authorial photographic albums which had a combined print run of nearly half a million copies.[2] In terms of the number of publications, Hartwig places within the absolute top of photographers active in the second half of the twentieth century, not only in Poland but throughout Central Europe.[3] And it is those publications that to a decisive degree contributed to his mass popularity.

Library

Until recently photography books were not the object of special interest among researchers of the history of photography, but artists and collectors are beginning once again to appreciate their qualities. They require particular attention in the case of Edward Hartwig, who not only declared many times his attachment to this format, but was also the author of at least a few canonical photo books. Publications like Fotografika[4] are standalone works of art, with a specific structure, content, cultural context and reception. They often have a greater significance for the authors’ work and career than exhibitions or individual photographs. This was also the case for Hartwig. From the mid-1950s, work on successive photo books imparted a rhythm to his activities. As he said, “I make albums often at the cost of my own creative work. I simply want to leave a trace of myself behind.”[5] Hartwig’s exhibitions, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, served to lay the ground for issuance of photo books, although it sometimes happened that the publications preceded the exhibitions[6] or became a part of them, as in the case of the individual exhibition at Zachęta in Warsaw in 1979, at which “eighteen authorial albums” were presented alongside the photos.[7]

All of this shows that Hartwig understood perfectly the importance of the photo book as a modern medium. For him it was a natural form of expression, combining ideally with a characteristic element of his photographic craft: graphic transformation, cropping and re-editing of negatives (often after many years). As he explained:

Constructing an album is always a fascinating adventure for me and great fun. I lay out a pair of pictures on the floor and think, this doesn’t fit. I reach for the archive, make an enlargement, swap them out and check whether I’m right or not. Time serves as a certain judge, as emotion dissipates and the intellect does more work.[8]

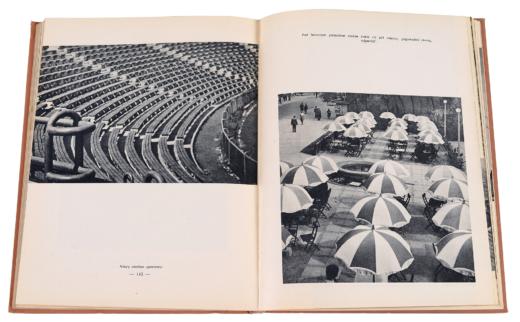

Edward Hartwig, ‘Lublin’, Sport i Turystyka, Warsaw 1956

Critics and historians, but also Hartwig himself, linked this exceptional method with his youthful fascination with painting and his two years of study at the Graphic Institute in Vienna in the 1930s. Another key aspect of his Vienna experience is mentioned less often. As Hartwig recalled:

When I came to Vienna, the first thing they did was send me to the library. They ordered me to see and examine everything, and somehow come to terms with it. There I saw all the American albums. I saw so many different things you can do in photography.[9]

The artist’s mature manifesto, Fotografika, would not appear until a quarter-century later, but maybe the first artist in Polish history to consciously and consistently employ the medium of the photo book was born in that Vienna library.

Politics and art

The first printed photo books appeared in the late nineteenth century, driving out, thanks to new printing technologies, the previously popular album publications with pasted original prints. This change meant lower costs and higher print runs, which allowed photo publications to become part of the modern mass visual culture. At first they contained primarily landscape, documentary and journalistic photography. It was only in the 1920s, in Europe and the United States, on the wave of modernist and avant-garde explorations, that the formula for the photo book was transformed into a full-fledged, individual artistic expression.

The first fully authorial book of Hartwig’s was the impressive album Lublin from 1956, published by Sport i Turystyka (…). It contained an eclectic set of photos from pre-war and post-war times. Most of them depict the Old Town, which in the propaganda plan was supposed to serve as the hallmark for the rebuilding of the city.

Tadeusz Rząca, a creator of autochromes who exploited the possibility of duplicating colour photographs in print, may be considered a precursor of explorations of this type in Poland.[10] His only photographic album, strongly inspired by Young Poland painting, appeared in 1920 and for the next half-century remained the only full-colour Polish photo book.[11] The brochure edited by Aleksander Minorski Dola i niedola naszych dzieci (Our children’s fortunes and misfortunes)[12] was of an entirely different nature: a unique example of socially engaged photography, in formal terms close to the rhetoric of the avant-garde. Unfortunately, due to a decision by the sanitation authorities, nearly the entire print run was pulped. The no less legendary book by Henryk and Janina Mierzecki, Ręka pracująca (The working hand), was an original combination of explorations in modern photography with scientific research on dermatology.[13]

After the Second World War, the need for photographic publications grew dramatically in Poland, mainly due to the propaganda apparatus, producing at first flyers and brochures, and sometimes books and impressive albums, legitimizing the new political and social order and documenting the process of rebuilding the country. Even if the hard rhetoric of these publications raised doubts, particularly among photographers with pre-war experience, the demand they created gave photographers a solid opportunity to earn a living—not to be despised during the difficult post-war period.

One of the beneficiaries of this situation was Edward Hartwig, who in 1947 became a founding member of the Association of Polish Art Photographers (ZPAF)[14] and four years later moved with his family to Warsaw. Photos by Hartwig and his wife Helena illustrated a number of popular propaganda publications,[15] including the group album Ziemia rodzinna (Family earth), issued by Nasza Księgarnia, which specialized in literature for children and youth.[16] This was the first longer publication for which Hartwig was responsible for selecting and arranging the photos (most of which were by him). Landscape photos in a pictorial manner, supplemented by poetic works, predominate.

Hartwig’s contacts with publishers resulted in the mid-1950s in the first titles illustrated entirely with his own photographs. A brochure about Lublin was issued in 1954 by Sport i Turystyka, a publishing house the artist was to cooperate with for the next forty years.[17] A year later, Sztuka[18] published two documentary and landscape collections of his photos: Lublin. Stare Miasto (Lublin: The Old Town)[19] and Łazienki (on the royal park of that name in Warsaw). These were not full-fledged albums, but portfolios wrapped in a dust jacket, comprising a dozen or so loose sheets with reproductions, along the lines of old graphic and photographic folios.

The first fully authorial book of Hartwig’s was the impressive album Lublin from 1956,[20] published by Sport i Turystyka in a cloth cover with a photographic dust jacket and full-page reproductions. It contained an eclectic set of photos from pre-war and post-war times. Most of them depict the Old Town, which in the propaganda plan was supposed to serve as the hallmark for the rebuilding of the city. Romantic shots of Old Town alleys with painters posing at their easels, following the pictorial “misty” convention, were accompanied by dynamic shots of post-war builders on scaffolding. There are also graphic rhythms of snow-covered roofs and geometrical compositions of garden-café umbrellas, i.e. more modern shots heralding a new, thaw-era photographic idiom. Lublin was Hartwig’s first exercise in composing foldouts, a practice on which he would base future albums, including the crucial Fotografika. So we find here a foretaste of later fully authorial art books, but also further publications of a landscape nature, largely subordinated to schemata imposed by state publishers. 1957 saw the release of Kazimierz nad Wisłą,[21] which launched a series of albums devoted to cities and regions around the country.[22] Some of them would be reissued in new editions by the author, and their print runs, from 15,000 to 30,000, were typically about three times greater than for Hartwig’s purely artistic publications.

Edward Hartwig, ‘Lublin’, Sport i Turystyka, Warsaw 1956

Landscape albums, whose production expanded for good in the mid-1950s, became a characteristic format for post-war visual propaganda. They filled Polish bookstores, Empik clubs, and libraries, becoming—alongside the inseparable bouquet of carnations—a popular workplace commemorative gift. Initially there were photographically interesting titles—apart from Hartwig, Franciszek Myszkowski,[23] Henryk Lisowski[24] and Andrzej Brustman[25] should also be mentioned—but the format of the albums quickly underwent standardization in content, layout and the convention of the photos. They usually presented the most significant landmarks of the city or region, followed by documentation of new socialist development projects: schools, housing estates, and industrial plants. Hartwig broke with that cliché in a successful volume devoted to the Pieniny mountains[26] and in an album on Warsaw, issued in the 1970s.[27] The latter opened with an impressive sequence of photos, made using the wide-angle fisheye lens fashionable at that time, depicting the newly completed architectural complex known as the Eastern Wall.

Hartwig’s involvement in mass tourism-oriented production (his photos were also published on postcards by the state monopolist, Ruch) obviously had an economic subtext, but the artist also pointed to other motivations: “I discovered that photography offered a certain independence,” he explained. “And I didn’t want to be dependent on politics, influences or interests. … I was always interested in the landscape.”[28] Despite his claim that he was pursuing themes free of political conditions, Hartwig sharply differentiated landscape photography from his artistic practice:

I was sometimes accused of departing from “pure photography.” But such pure photography can occur only in albums like Lublin or Pieniny, where I present pictures reporting on nature, and not interpreting it. In an album I’m not allowed to interpret the Acropolis, but at an exhibition I can convey my most outlandish vision.[29]

This peculiar pragmatism of Hartwig’s, generating for him extensive work with landscape documentaries and creative photography, did not betray opportunism, but a specific understanding of photography as a primarily practical field. Hartwig more than once stressed that he chose the profession of a photographer first for economic reasons, and discovered its artistic potential only with time.[30]

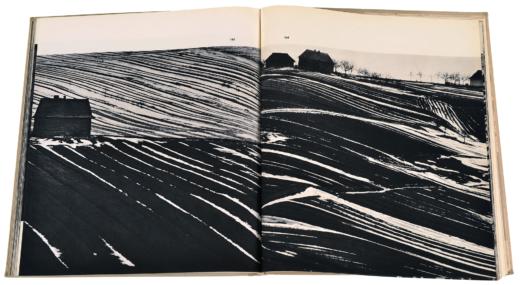

Edward Hartwig, ‘Rhythm of early Spring’ in ‘Fotografika’, Arkady, Warsaw 1960

Fotografika

It is the fully authorial art books that constituted the second and much more intriguing stream in Hartwig’s publishing practice. At the end of 1960 his most important book appeared: Fotografika (Photographics), the first and for a long time only fully authorial, programmatic artistic statement in Poland in the medium of a photographic album. It arose out of a wonderful concatenation of circumstances: the specific historical moment, new technical possibilities, and last but not least, the creative competencies and unusual intuition of the author. If we can credit his recollections, the book arose in an atmosphere of enthusiasm and spontaneous elation shared by both the artist and the publisher. Hartwig created the mock-up of the book after his return from the Paris show Fotografika, probably in the summer of 1959.[31] The book included photos shown at the exhibition as well as new ones made during Hartwig’s foreign journeys, among other places to Paris, Italy, Yugoslavia, and Brussels, where he visited the world’s fair Expo 58. “I thought people would find it interesting,” he commented years later. “I felt a little obligated to do it, because people didn’t travel outside the country much in those days.”[32]

Essentially, Poland had experienced a brief euphoria connected with the political thaw and liberalization of cultural life following the events of Polish October in 1956. Art, frozen by the episode of social realism, quickly made up for lost time, and artists travelled a lot, caught up in the whirl of modernity and taking advantage of the boom on the other side of the Iron Curtain. On the pages of Fotografika, which is a document of this revival, Polish landscapes interweave with views of modern Western architecture. Twenty years after his studies in Vienna, Hartwig returned to the European salons.[33] As he stressed many times, the book brought him international popularity and led to numerous international exhibitions: “If I later had some exhibitions in various countries, it was thanks to that album. I am very grateful to it for that. And when they greeted me at the airport, somewhere where they didn’t know what I looked like, they would hold up that album.”[34] It must have been an unusual sight—like the book itself. On the Polish publishing market of that time, it stood out not only for its content, but for its editorial flair: a cloth binding, an impressive dust jacket, specially prepared paper,[35] but most of all the non-standard, large, nearly square 32×28 cm format. A symbol of the global ambitions of the author was the flyleaf, with emblems of the international salons and shows from 1955–1958 in which, it may be inferred, he took part.

Fotografika exudes the spirit of the thaw. This is manifest not only in its cosmopolitan aura, but in the characteristic iconography. The album opens with a sequence of a dozen or so portraits of girls and young women in the style colloquially referred to as kociaki (“pussycats”),[36] which Hartwig, falling in with the poetics of the grotesque popular at the time, juxtaposes with the countenance of a dog, the expressive, wrinkled face of an old man, or a face drawn in the snow covering a chopped tree trunk. The next sequence is devoted to the graphic and rhythmic qualities of modern architecture and luminous etchings of urban nightlife. Next we see Old Town alleys in shots alluding to the aesthetic of neorealism,[37] followed by foldouts in a spirit of artistic bricolage, with views of film sets, theatre prop rooms, flea markets, artists’ studios, and scenes from urban life in painterly shots. They smoothly segue into a sequence of stage shots—fragments of drama and ballet performances. The album is crowned by an extensive set of landscape studies, most having undergone strong “graphicization,” which somewhat unexpectedly in this modern rhythm of images contains several shots of traditional “rural types.” Fotografika presents various genres of depiction: portrait, nude, landscape, still life, and abstraction. It comprises a kaleidoscope of themes, a visual journey through various fields of the cultural landscape, not necessarily semantically coherent but full of artistic vitality.

“Constructing an album is always a fascinating adventure for me and great fun. I lay out a pair of pictures on the floor and think, this doesn’t fit. I reach for the archive, make an enlargement, swap them out and check whether I’m right or not. Time serves as a certain judge, as emotion dissipates and the intellect does more work.”

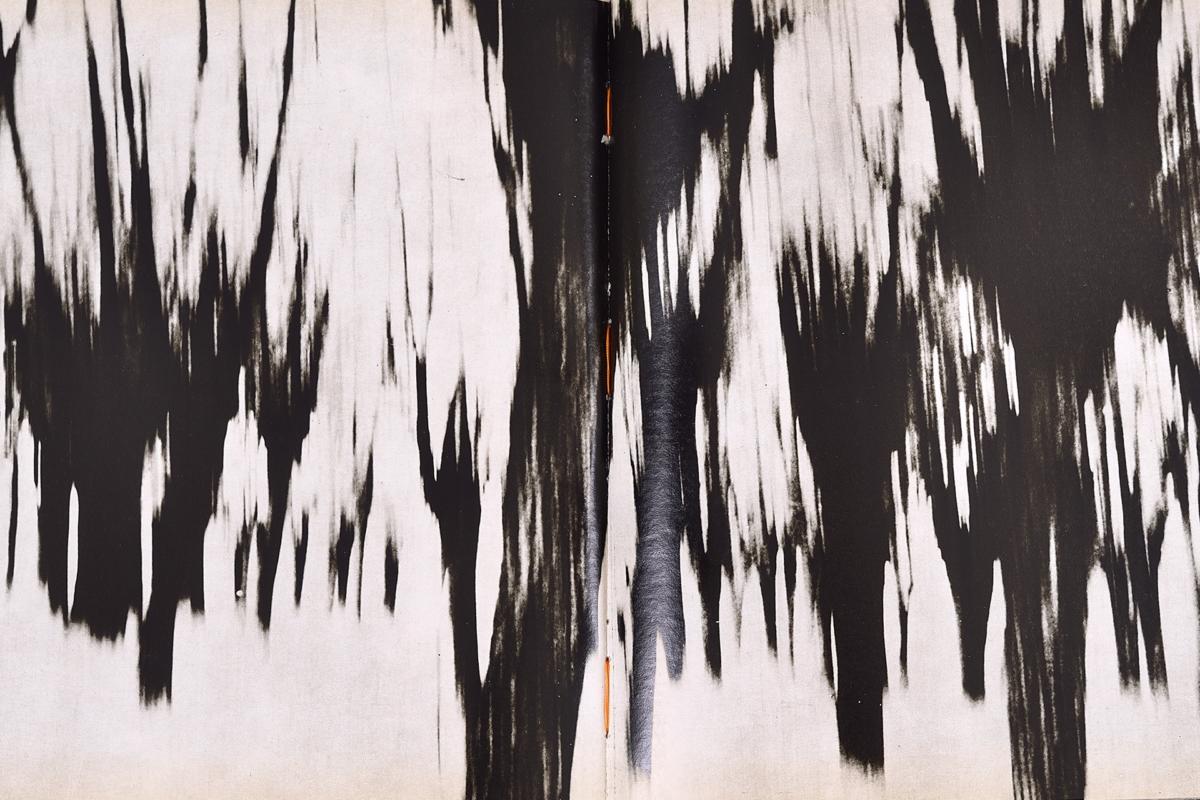

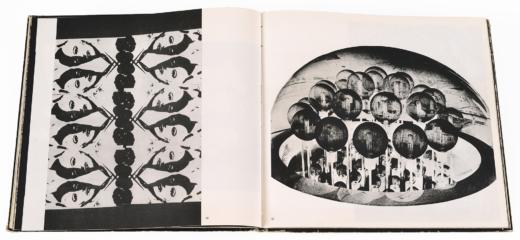

The fundamental structural principle of Fotografika is the rhythm of “photographic suites.” This is how Hartwig referred to the pairs of photographs spread across foldouts, occupying all or nearly all the surface of the page. These suites, of which there are ninety-four in the book, have their own titles hinting at the author’s intentions (e.g. Femina, Poziomy i piony (Horizontals and verticals), Tragedia lalki (Doll tragedy), Abstrakcja (Abstraction), Oko (The eye) and Rytmy przedwiośnia (Rhythms of early spring)).[38] These suites, close in technique to photomontages,[39] build tension and determine the characteristic poetics of Fotografika. Exploiting the peculiarities of the medium of the book, Hartwig submits his images to artistic confrontations. He contrasts the portrait of a schoolgirl dressed in fine black-and-white stripes with the rhythm of dark fence palings against a winter landscape. The face of a girl seen through her long, flowing blond hair is juxtaposed with the view of a ski slope sliced by ski tracks. A plane-tree trunk is spliced with the blank wall of a Paris tenement building, covered by patches of old plaster. These clever, often non-obvious associations are not just a play of form, content and meaning. Behind them lies a special method of viewing reality: a modernist eye seeking abstract visual structures in bodies, houses, and landscapes. This is the essence of Hartwig’s vision: the image recorded on the negative is the raw material for further work in the darkroom and a quest for advanced artistic effects.

The author subjected the photos published in Fotografika to a range of postproduction treatments. The simplest of them was cropping, which often drastically altered the original meaning of the shot. The radicalism of these operations can be traced by consulting photos known from other publications or collections. For example the photo Malarnia (Paint shop, no. 69 in the album) presents a headless and armless torso of a female mannequin and a dancer standing beside it—the dancer also “decapitated,” especially for the purpose of this publication.[40] An even more interesting example is the photo titled Wakacje–Polska (Vacation–Poland, no. 173), depicting a group of children running along a path through the fields between trees. Another shot cropped from the same negative, known from private collections, reveals a tall roadside cross standing in the foreground. But the cropping did not always entail such significant choices bordering on self-censorship. It was usually a natural operation used to obtain a satisfying effect in a single photograph, but in the suite was used to achieve an effect in the foldout. Hartwig often returned to the same photos, or even completed montages, and reworked them. Fotografika, which he continued to prize years later,[41] became for him a kind of living archive from which he drew not only inspiration, but also specific photographs, published in new variants or croppings.[42] The second edition of the album, published just two years after the first, already contains a number of changes in the arrangement of the foldouts and in the selection of individual photos.[43]

Edward Hartwig, ‘Femina’ in ‘Fotografika’, Arkady, Warsaw 1960

Another treatment emblematic of Hartwig’s work at that time was “graphicization” of photographs through strong dialling up of the contrast, often until obtaining an entirely black and white image. This effect achieved sharpness through the use of rotogravure, which at the time was the basic technology for printing photography in Poland. It was characterized by deep blacks and strong contrast. As Hartwig recalled, “I abandoned halftones and made photographs in black and white. This was a novelty, and in rotogravure it became even more spectacular. People were shocked by my ‘graphic’ vision, and often asked whether this technology was specially applied.”[44] He explained his inclination toward flat, graphic compositions by his fascination at that time with the poster, which since the early 1950s had enjoyed a reputation as the freest and most creative field of art in Poland and played the role of an export good of Polish culture.[45] But the point in Fotografika was not so much to make the pictures poster-like, but to “iconize” them—abstracting the flat motif from the illusionist photographic image.

This studied formal agenda was also the ideological message of Fotografika. For Hartwig, the essence of the photographic art was the subjective processing of reality, patterned on the practice of graphics or painting. He intended the title of the album as a synonym for artistic photography, i.e. photography rejecting utilitarian functions to rely on the processing of an image of reality exposed on a roll of film. Hartwig accurately sensed that the neologism fotografika, introduced into Polish in the late 1920s by Jan Bułhak, still had great semantic potential. At the same time, the word conveyed in the simplest possible way the essence of his method: “photo graphics.” Inter-media artistic games of this type, exploiting issues of rhythm, movement and space, were a hot topic of the visual arts at the turn of the 1960s. With his vision of photography—graphicized, close to the grotesque and abstraction—Hartwig fit perfectly within the contemporaneous canon of modernity.

The allusion to Bułhak, from Wilno (now Vilnius), the founding father of Polish artistic photography and author of another volume titled Fotografika, published in 1931,[46] was undoubtedly a carefully considered gesture but not commented on. Bułhak’s book was primarily a programmatic text, not very extensively illustrated with photographic works. Hartwig, who by then had already distanced himself from Bułhak’s attainments,[47] entirely rejected Bułhak’s pictorial manner and redefined the artistic agenda of photography in the spirit of late modernism. This updating of Bułhak’s neologism smacked of expropriation, and from then on it clung to the name of Hartwig, the leading photographer of communist Poland.[48]

Although the reviews of Fotografika—the exhibition and the book—were far from unalloyed enthusiasm, with time Hartwig’s album attained the status of a cult publication, cited in the recollections of successive generations of photographers.[49] It became the touchstone for the following projects by the artist, but also for a growing group of “photo-graphists.” Against the background of the very modest publishing output in Poland at the time, Hartwig’s work was a total sensation, in terms of both artistic ambitions and editorial panache. It can only be compared to Jan Styczyński’s album Koty (Cats) published the same year—artistically appealing but carrying an entirely different specific gravity.[50]

The fundamental structural principle of Fotografika is the rhythm of “photographic suites.” This is how Hartwig referred to the pairs of photographs spread across foldouts, occupying all or nearly all the surface of the page. These suites, of which there are ninety-four in the book, have their own titles hinting at the author’s intentions (…). Close in technique to photomontages, they build tension and determine the characteristic poetics of Fotografika.

Fotografika was also quite exceptional in an international context. Authorial albums, like those with artistically advanced processing of photographs, were few and far between at that time. Scattered examples from Japan,[51] Switzerland,[52] and Hungary[53] are somewhat later than Hartwig’s book. It does, however, perfectly suit the agenda for “subjective photography” (Subjektive Fotografie) popularized in the 1950s by Otto Steinert. This German amateur photographer, lecturer and curator used this term to refer to artistic photography that takes up formal experiments and rejects verism in favour of individual expression and graphic effects—exactly the sort of photography practised by Hartwig. The celebrated albums Subjektive Fotografie[54] and Subjektive Fotografie 2,[55] compiled by Steinert, were the forerunners of Fotografika. They had a similar thematic scale and visual quality, as well as similar foldouts relying on artistically intriguing and semantically arranged photos. It may be assumed that Hartwig was quite familiar with this concept and particularly its materialization in Steinert’s albums. The methods of subjective photography were eagerly applied in other publications, such as Almanach fotografiki polskiej (Almanac of Polish photography),[56]an annual published from 1959 under the auspices of ZPAF. Steinert’s own publications also took the form of an almanac—a precisely composed collection of pictures by many photographers. But Hartwig created his Fotografika all on his own. Perhaps even selfishly, as the ideas realized there—his own and those observed elsewhere—could have been successfully shared among a large group of subjective photographers.[57]

My Land and Greek land

Two years after the first edition of Fotografika, and alongside the second edition, appeared the second authorial book by Hartwig, Moja ziemia (My land).[58] The artist, only just manifesting his access to cosmopolitan modernity, expressed in this volume his surprising affinity for a Bułhak-like approach to native photography. “Showing the beauty of my own country was an outright patriotic duty,” he recalled years later. “I alluded to the impressionists and tried to carry over some of their experiences into my frames. I rose before dawn to take pictures of the fogs, the sunrises, the fields and trees.”[59] Moja ziemia marked a return to the formula of the landscape album, as elaborated back in the 1930s[60] and grasped eagerly during the era of socialism. In his focus on the theme of the landscape, it recalls the earlier Ziemia rodzinna edited by Hartwig. The classical narrative, arranged in order by the seasons of the year, alludes in turn to the impressive album Cztery pory roku (The four seasons), prepared “for export,” which also included a few photos by Hartwig.[61] Despite the somewhat modernized artistic idiom, Moja ziemia was far from the boldness of the foldouts in Fotografika. At the same time, the minimalist layout, the absence of captions under the photos, the author’s introduction and the literary foreword by the poet (and the artist’s sister) Julia Hartwig all suggest that this is a purely artistic statement. In his introduction, the artist referred to the origins of his practice: “Ever since I began photographing, I have photographed the Polish landscape.”[62] Hartwig thus displayed in Moja ziemia a more conservative side to his artistic personality. The inclusion of a few shots of tractor farmers working the fields—an emblematic motif of social realist iconography—may in turn be read as a slight bow to the state publisher, not very glaring in the context of the whole work.

Cover for the ‘Almanac of Polish Photography’ 1960

An interesting counterpoint to the studies of the native landscape was the album Akropol (Acropolis),[63] an unorthodox impression from a visit to the most important Athenian hill, produced together with Tadeusz Sumiński and published in 1964 by Arkady.[64] The living documentation of ancient ruins, with interesting closeups, shots from a worm’s-eye view, strongly contrasting effects of light and shadow, is interwoven here with partly anecdotal and partly reflective observation of tourist traffic. The photographers’ artistic aspirations contrast with the erudite text by Kazimierz Michałowski, the distinguished archaeologist and classicist. This encounter between photographer and scholar ultimately gave rise to a series of similar albums shot in the following years by Andrzej Dziewanowski, still cooperating with Michałowski. Akropol remained Hartwig’s only publication devoted entirely to his numerous foreign travels.[65]

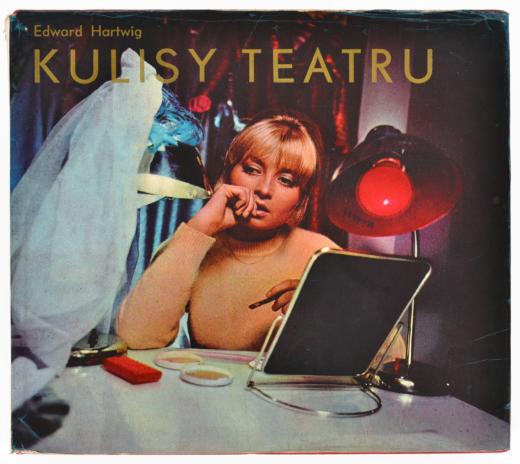

Backstage

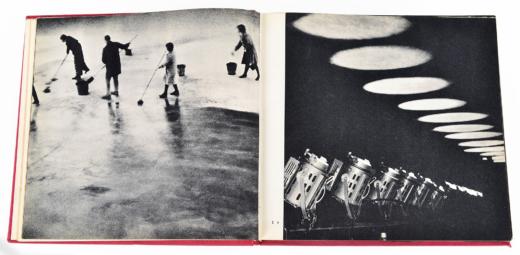

Hartwig’s second most-famous book, Kulisy teatru (Backstage),[66] appeared a decade after the programmatic Fotografika. Since the early 1950s, when Hartwig moved to Warsaw, theatrical photography had constituted the basic, and apparently entirely satisfactory, source of the artist’s livelihood. This occupation also had an important personal subtext, as theatrical photography was also pursued before the war by the artist’s father, Ludwik Hartwig.

Edward Hartwig varied his ongoing work documenting shows with his peregrinations around the titular backstage, to the dressing rooms, rehearsal studios, and, particularly appealing for him, the set workshops.[67] The fruit of these excursions was a book with a handy nearly square format,[68] containing 227 black-and-white photos divided into four thematic sections: scenography; directors and actors; ballet and pantomime; and puppet theatre. Each of them has its own dynamic and is a type of photographic study. The photos, one per page, with nearly iron consistency adhere to the layout imposed by the graphic designer (with a bleed at the outer edge of the page and a small margin on the inner side). All of the pictures have captions, typically identifying the location and the characters. The result was a broad panorama of Polish theatre of the 1950s and 1960s. Hartwig intentionally refused to focus on a single specific theatre, director or show, as in the book the creator of the theatre was to be not the director or the stage designer but the photographer. The theatre became a theatre of photography, photographic staging, a world apart. And indeed, in communist Poland theatre was an enclave of limited freedom—for the theatre artists and the photographer accompanying them. Kulisy teatru is thus an expression of this situation, but also a propagandistically convenient advertisement for blossoming socialist culture.

But the formula of an informational document was alien to Hartwig. Kulisy teatru is a type of subjective, contemporary, and in places experimental, artistic photo-reportage. Alongside triumphal portraits and genre scenes there are still lifes, closeups, graphicizations, and nearly abstract records of the play of light and stage motion. The book is dominated by the faces of actors and theatre people, giving the whole a humanistic, nearly Steichenesque[69] expression—this is after all the family of the theatre viewed from the wings, at moments of exaltation, ordinariness, and small drolleries. Hartwig strives here to avoid pathos and rapture at the celebrity side of acting. It’s not surprising that Kulisy teatru has joined the canon of contemporary literature on this theme.[70]

Edward Hartwig, ‘Kulisy teatru’, Arkady, Warsaw 1969

Photographic themes and variations

The agenda of Hartwig’s photographics is closed out, nearly twenty years later, by two books released at the same time by two different publishers: Tematy fotograficzne (Photographic themes)[71] and Wariacje fotograficzne (Photographic variations).[72] They approach Fotografika in photographic conception and in the composition of the albums. They are decidedly more modest in format and length, but maintain a similar, nearly square shape. They are dominated by strongly processed works: the familiar inversions and contrasting black/white compositions with eliminated halftones, as well as illuminated photomontages and enlargements made from two negatives at the same time, creating an interesting effect of interpenetration. In the Wariacje album, more interesting in editorial and printing terms, figural motifs predominate, including theatre, ballet and pantomime scenes. There is also an extended sequence of female nudes. “Theatre is in some sense an artificial creature,” Hartwig commented. “And I soaked up this beautiful and wonderful artificiality, and under that influence made this album. Wariacje fotograficzne is unreal situations created by me. I am making my own theatre.”[73] Meanwhile, in Tematy diverse motifs interweave without any clear dominant theme. It is his first publication in an explicitly retrospective strain, opening with the transcript of a discussion in which Edward Hartwig recounts to Julia Hartwig the tracks of his life and artistic career.

Both books were published in the late 1970s, a time when creative, subjective photography had clearly begun to lose steam. While Zofia Rydet’s extended series of photomontages Świat wyobraźni (World of feelings and imagination) appeared in 1979, Rydet herself had begun work a year earlier on her groundbreaking Zapis socjologiczny (Sociological record), the work that set a new direction for artistic photography in Poland. The 1970s were also a decade of intensive experiments in the field of conceptual photography, by Andrzej Lachowicz, Natalia LL, and others. But first and foremost, after Karol Cardinal Wojtyła’s election as pope, the political climate in Poland changed, and laboratories of pure art began to empty out. Politics, which Hartwig had tried to steer clear of, unexpectedly arrived on his doorstep uninvited. The censors made drastic changes to Wariacje fotograficzne in the preparations for printing. The album, designed with graphic artist Czesław Wielhorski, was supposed to be of a photographic/literary nature, and fragments of texts and poems selected by Julia Hartwig were to be printed on sheets of tissue paper separating the photographs. As Edward Hartwig recalled:

At that time a group of intellectuals had signed a list to the Sejm on the constitution. My sister signed it too. Then the publishing house withdrew all of the texts and her name when the book was already at the printer’s. Without my knowledge. I tried to intervene, but they told me that the order came from on high, and the album would not appear with those texts. And they inserted an introduction—which was in fact interesting—by Kira Gałczyńska. I even deliberated for a while whether to give up on the whole venture, because it was a great unpleasantness for my sister. But it happened as it happened.[74]

Ultimately, graphic motifs abstracted from the photographs were printed on the tissue sheets. As a result of these difficulties, but also due to the political and economic crisis of the 1980s, Hartwig lost his publishing momentum.

Edward Hartwig, ‘Kulisy teatru’, Arkady, Warsaw 1969

Poland in colour

Hartwig’s oeuvre was based on black-and-white photography. Relatively late, not until the 1990s, the artist began to discover the potential of colour photography. It is true that he published colour photos in his landscape albums in the 1970s, but, as he recalled, this was due to pressure from the publishing houses, which were trying to catch up to global standards, usually with unconvincing results. Hartwig’s first publishing project carried out mainly in colour was Kwiaty ojczystej ziemi (Flowers of the native land)[75] in 1983. The book had an atypically tall and narrow format, which combined with the poor quality of the colour reproductions meant that Hartwig’s photos—landscape studies, including numerous shots of wildflowers—did not come across persuasively. The interesting graphic design by Jolanta Marcolla, an artist affiliated with the stream of conceptual art, did not help. The sequences and repetitions of small illustrations she concocted did not entirely suit Hartwig’s photos, which generally worked best on a large scale. The photos were again accompanied by poetry.[76] It was no doubt due to his youthful artistic fascinations that Hartwig returned to the idea of combining photographic images with literature. In his Lublin days he has moved in circles of painters and writers, later maintaining these contacts in part via his sister Julia.[77] With time these expedients, probably arising out of an ambition to ennoble photography as a young artistic medium,[78] degenerated into a rut.

After 1989 Hartwig returned to the theme of the Polish landscape. The impressive album Polska Edwarda Hartwiga (Edward Hartwig’s Poland)[79] arose in happily altered realities—in politics but also in publishing and printing. The demand for a new form for elegant albums, executed now by private publishers, coincided with experiments taken up by Hartwig with colour photography. This book was composed of black-and-white landscape photos from various periods of Hartwig’s creative work, but also contained a few vivid foldouts with his latest colour photos, which were printed to bleed on the edges and, though not numerous, set the rhythm for the whole work.

The true summation of the artist’s long path was two themed albums, Wierzby (Willows) and Halny (Mountain wind). They are divided by time and printing possibilities, but joined by a focus on a selected theme of the landscape and by the poetics and distinct symbolism of expressive black-and-white photographs.

Towards a self-portrait

Near the end of his life Hartwig eagerly returned to his earliest photographs—“misty” landscape studies, pictures of old Lublin, Kazimierz and surroundings. He prepared albums devoted to them which were ultimately published by the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press, which cooperated intensively with the artist in the late 1990s.[80] Until then, Hartwig’s photos from the 1920s and 1930s had not been widely published in book form, so apart from their sentimental value these albums also filled out Hartwig’s creative CV.

But the true summation of the artist’s long path was two themed albums, Wierzby (Willows)[81] and Halny (Mountain wind).[82] They are divided by time and printing possibilities,[83] but joined by a focus on a selected theme of the landscape and by the poetics and distinct symbolism of expressive black-and-white photographs. A few pictures from the Halny series had appeared for the first time in Wariacje fotograficzne, while willows, an emblematic element of the Polish landscape, were a fixed motif in Hartwig’s oeuvre. As he wrote:

I could even compare myself to a willow. It is a tree that could in all facets suggest my personal, private and artistic experiences. You can befriend a willow. You can talk with a willow. I think that any befriended willow may be a synthesis of my personality, my life’s course. Entering a willow would eliminate for me so-called “unnecessary journeys.” I have come to believe that here, ready to hand, next to us, close by, are such fascinating things, simple, everyday, unnoticed by many.[84]

Wierzby, a concentrated and exhaustive photographic study of this species of tree, includes landscape studies, expressively captured details, as well as jogged frames close to abstraction. Some of the photos date to before the war. As the statement by Hartwig quoted above suggests, this album may be regarded as the final and extreme fulfilment of the agenda of subjective photography. The photographer approaches identification not only with his own work, but, through a radical artistic processing of the selected motif, also with the photographed fragment of reality.

Halny is Hartwig’s last authorial, thematic book. It is thus easy to ascribe to it the nature of a personal valediction, particularly as it employs an already well-known photographic idiom. It is nonetheless a distinct and original work, and unfairly neglected. The narrative is divided into prologue, part one, part two, and epilogue. This structure, not typical of Hartwig’s books, builds suspense and further submission to the fleeting and invisible phenomenon of the wind. Between frames depicting shaken tree limbs are photos of roadside crucifixes, which introduces the cultural context of the Podhale region to a story of nature, thus fuelling its symbolic eloquence. As is usually the case with Hartwig, the narrative is built from pictures taken at different places and times, but nonetheless is captivating in its suggestiveness and density. Halny stands out from the many landscape albums not only for its artistic culture, but for its original theme: surprisingly, the legendary Tatra wind, reaping its harvest in trees and people, has not attracted a very extensive photographic literature. As the culmination of Hartwig’s forty-year publishing practice, this theme resonates especially strongly.

Edward Hartwig, ‘Wariacje fotograficzne’, Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, Warsaw 1978

Radical and applied photography

As I mentioned, Hartwig rejected the artistic idiom of Jan Bułhak’s photography. He was nonetheless his conscious successor in terms of the professionalism of his artistic practice: broad promotion of his work, participation in salons, exhibitions, and industry publications, but also engagement in production of albums, which he regarded as a duty of a modern photographer. In his Fotografika Bułhak devoted much space to the issue of the unsatisfactory level of print reproduction of photographs in Poland.[85] This problem, all-too current under post-war conditions, also caused many disappointments for Hartwig, who understood well that in the twentieth century the book had become one of the basic media for popularization of art. It appears from the end of the 1950s that work on successive albums was more important for him than a number of other obligations. In the press reports from Hartwig’s exhibitions away from Warsaw there is repeated mention of the disappointment that the artist did not take part in the opening or in the preparations for the exhibition.[86] When asked about his creative plans, he generally mentioned the themes of the upcoming books he was working on at the time.[87] This is not surprising. The medium of print gave him the possibility of graphicization, contextualization and re-editing of his pictures. These new tools of artistic expression freed him from the limitations of the negative and the camera,[88] which—in a radicalized version of Bułhak’s view—he deemed a necessary evil.[89]

Photography books, until recently marginalized, have finally achieved recognition, as Hartwig correctly sensed they would, as a full-fledged form of artistic expression, independent of exhibitions or collectors’ prints. They have also become an important subject of research. It is only when we examine Hartwig’s oeuvre through the prism of his books that we clearly perceive the various dimensions of his work: radical, artistic, but also opportunistic, measured by successive landscape albums compliant with the official rhetoric of the visual propaganda of the Polish People’s Republic. His most important book, Fotografika, helped him redefine himself at the age of fifty. In it he achieved a level of photographic editing probably unmatched by any of his exhibitions. He created in it a modern agenda for artistic photography: a canon of themes and techniques characteristic for himself, some of which could only be realized in print. He became the patron of this agenda, and later its devoted hostage.

The text comes from the book Fotografiki, published by Fundacja im. Edwarda Hartwiga, edited by dr Marika Kuźmicz.

[1] E. Hartwig, Tematy fotograficzne (Photographic themes) (Warsaw 1978), p. 12.

[2] Bibliographies of Edward Hartwig’s book publications are found in catalogues of his various exhibitions and on Wikipedia. Hartwig himself used the term “authorial book” (książka autorska) loosely, and the bibliographies also include works he co-authored, or for which he authored only the photographs or some of the photographs.

[3] See Ł. Gorczyca & A. Mazur, Fotoblok. Europa Środkowo-Wschodnia w książkach fotograficznych (Photobloc: Central & Eastern Europe in photographic books) (Kraków 2019).

[4] E. Hartwig, Fotografika (Photographics) (Warsaw 1960).

[5] I. Wojciechowska, “Świat w obiektywie” (The world in a lens), Słowo Polskie, 21–22 April 1979.

[6] For example the album Wierzby (Willows) from 1989.

[7] W moim świecie 1930–1978 (In my world 1930–1978), exhibition catalogue (Warsaw: CBWA Zachęta, 1979), p. 2.

[8] E. Hartwig, “Psy czy koty? Fotografia czy fotografika? Kolor czy…?” (Dogs or cats? Photography or photographics? Colour or…?), interview by A.B. Bohdziewicz, Format 1997 no. 24/25, available online at <fototapeta.art.pl/fti-ehabbf.html>.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Rząca even founded his own publishing house, Autochrom, which released a series of colour postcards from his Kraków autochromes. His views of the Tatras, Kalwaria Zebrzydowska and areas around Kraków were also reproduced by other publishers of postcards during and immediately after the First World War.

[11] Tadeusz Rząca, Malownicza Polska. Ziemia krakowska (Colourful Poland: Kraków lands) (Lwów n.d., c. 1920).

[12] Dola i niedola naszych dzieci (Our children’s fortunes and misfortunes) (Warsaw 1938); see also A. Mazur, Historie fotografii w Polsce 1839–2009 (Histories of photography in Poland 1839–2009) (Kraków 2009), pp. 177–178.

[13] Henryk Mierzecki, Ręka pracująca. 120 tablic fotograficznych (The working hand: 120 photographic plates) (Warsaw 1939).

[14] ZPAF has borne that name since 28 June 1952. Before that, from 10 February 1947, it operated as the Polish Association of Art Photographers (PZAF).

[15] Pictures by Hartwig are found among works by other photographers in albums such as Nasz sport. Na dziesięciolecie Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej (Our sport: At the tenth anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic) (Warsaw 1954); Nach der Arbeit (Warsaw 1954); MDM. Marszałkowska 1730–1954 (Marszałkowska Residential District: Marszałkowska Street 1730–1954) (Warsaw 1955); Nowa Warszawa w ilustracjach (The new Warsaw in illustrations) (Warsaw 1955); A. Brzezicki, Siła, radość, piękno (Strength, joy, beauty) (Warsaw 1955); Kultura Polski Ludowej. Wybór fotografii z lat 1945–1955 (The culture of People’s Poland: A selection of photographs from 1945–1955), (Warsaw 1956).

[16] E. Hartwig, Ziemia rodzinna (Family land) (Warsaw 1955).

[17] E. Hartwig, Lublin (Warsaw 1954).

[18] The Sztuka publishing house, founded in 1953, specializing in artistic album publications, was transformed in 1957 into Wydawnictwo Arkady. Many of Hartwig’s most important albums were published by one or other of these houses.

[19] Hartwig described the struggles with the creation of this publication in Fotografia magazine, see E. Hartwig, “Dlaczego Lublin?” (Why Lublin?), Fotografia 1955 no. 8, pp. 10–11.

[20] E. Hartwig, Lublin (Warsaw 1956).

[21] E. Hartwig, Kazimierz nad Wisłą (Warsaw 1957).

[22] E. Hartwig, Kraków (Warsaw 1964) (subsequent editions 1969 and 1980); E. Hartwig, Pieniny (Warsaw 1966) (2nd ed. 1971); E. Hartwig, Warszawa (Warsaw 1974) (2nd ed. 1980); E. Hartwig, Żelazowa Wola (Warsaw 1975); S. Morat, T. Papier & G. Rajchert, Łowicz (Warsaw 1975); E. Hartwig, Lublin (Warsaw 1983); E. Hartwig & E. Hartwig-Fijałkowska, Kazimierz Dolny nad Wisłą (Warsaw 1991); E. Hartwig, E. Hartwig-Fijałkowska & D. Saulewicz, Spotkania z Chopinem (Encounters with Chopin) (Warsaw 1995).

[23] F. Myszkowski & J. Wegner, Nieborów (Warsaw 1957).

[24] H. Lisowski, Żelazowa Wola: miejsce urodzenia Fryderyka Chopina (Żelazowa Wola: Fryderyk Chopin’s birthplace) (Warsaw 1955).

[25] A. Brustman & J. Iwaszkiewicz, Sandomierz (Warsaw 1956).

[26] E. Hartwig, Pieniny (Warsaw 1966).

[27] E. Hartwig, Warszawa (Warsaw 1974).

[28] E. Hartwig, “Olśnienia i fascynacje” (Illuminations and fascinations), interview by J. Wójcik, Rzeczpospolita, 10 October 1994.

[29] Edward Hartwig. Interpretacje część III (Edward Hartwig: Interpretations part III), exhibition catalogue (Toruń: Galeria Fotografiki Prezentacje, 1968), p. 3.

[30] “I painted a little, but it’s hard to sell paintings. I became permanently connected with photography when I fell in love. I had to start a family, live on my own account. The prose of life.” Hartwig, “Olśnienia.”

[31] Hartwig’s exhibition at the Société Française de Photographie, organized in cooperation with ZPAF, was a repeat of the earlier show Fotografika at Zachęta in Warsaw in February and March 1959.

[32] Hartwig, “Psy czy koty?”

[33] The first edition of Fotografika appeared in three language versions: Polish (10,200 copies), English and German (total of 3,200 copies). According to Hartwig, the foreign-language versions were distributed by a Dutch agent who bought up the rights to the foreign editions of the album. Hartwig, “Psy czy koty?”

[34] Hartwig, “Psy czy koty?”

[35] Ibid.

[36] The thaw-era fetishization of the image of the young woman has a broader context. See Ł. Gorczyca, “Krok w nowoczesność. Kultura wizualna PRL w latach 1955–1960” (A step toward modernity: Visual culture of the Polish People’s Republic 1955–1960) (master’s thesis, Institute of Art History, University of Warsaw, 1996), pp. 72–88.

[37] R. Lewandowski & T. Szerszeń, eds., Neorealizm w fotografii polskiej 1950–1970 (Neorealism in Polish photography 1950–1970) (Warsaw 2015).

[38] The list of titles was printed on a foldout sheet at the end of the volume, so readers could consult it while viewing the photos.

[39] Hartwig worked on juxtapositions of photos, pasting pairs of prints next to each other. Such montages are retained in the artist’s archive. These include variations known from Fotografika, but also ones that were never published—either rejected or prepared with a view to future publishing projects. See Fotografia kolekcjonerska. 15 edycja (Collectors’ photography, 15th edition), exhibition catalogue (Warsaw 2015), pp. 38–39.

[40] This photo was published in a fuller frame and under a different title, Tancerka (Dancer), in another of Hartwig’s books. Z. Pękosławski, Edward Hartwig (Prague 1966) (no. 29).

[41] Even in the mid-1990s Hartwig claimed, “Fotografika is my ‘impresario.’ To this day it stands the test of time. Most of the photos there, but not all, are works that are continually fresh.” E. Hartwig, “Hartwig o sobie” (Hartwig on himself), interview by Małgorzata Mach in Edward Hartwig, exhibition catalogue (Kraków: Muzeum Historii Fotografii w Krakowie, 1995), p. 11.

[42] For example, a portrait of a mime from the first edition of Fotografika (no. 116) returns in the second edition in a narrower crop (no. 118), and later, even more strongly cropped, in Kulisy teatru (no. 65).

[43] The second, revised edition of Fotografika, with a new dust jacket, a plain flyleaf, worse paper, and somewhat different arrangement of foldouts, appeared in 1962. Hartwig stressed that Fotografika was the only album of his accepted by the publisher without corrections (Hartwig, “Psy czy koty?”). We may suspect, however, that the changes in the second edition were at least partly forced on him. This applies in particular to the beginning of the album: in place of the original sequence of portraits of girls there are photos of the Warsaw Old Town and other views of historic architecture.

[44] Hartwig, “Hartwig o sobie,” p. 11.

[45] It cannot be ruled out that these statements contained a certain element of personal sentiment. Hartwig was friends with one of the founders of the Polish poster school, Józef Mroszczak, whom he met in the 1930s during his studies in Vienna.

[46] J. Bułhak, Fotografika. Zarys fotografji artystycznej (Photographics: An outline of artistic photography) (Warsaw 1931).

[47] This distaste, probably still underlain at that time by considerations of ambition, reached back to the pre-war years. Recalling his first exhibition in Lublin in 1929, Hartwig suggested that Bułhak showed up “uninvited.” Hartwig, “Psy czy koty?” Elsewhere he admitted frankly, “I don’t value Bułhak the artist very highly, but I recognize his great merit as an inspirer. … I did not imitate the style of his works.” Hartwig, “Hartwig o sobie,” p. 4.

[48] Adam Mazur writes in detail elsewhere in this volume on the essence of Bułhakian photographics, the post-war fate of this notion, and Hartwig’s reception of it.

[49] The artist and critic Jerzy Olek recalled that he received Fotografika from his colleagues for his eighteenth birthday. J. Olek, “Po prostu Hartwig” (Simply Hartwig), Nurt 1989 no. 6, p. 36.

[50] J. Styczyński, Koty (Cats) (Warsaw 1960).

[51] Y. Yoshioka, Yasuhiro Yoshioka (n.p., 1963).

[52] R. Mächler, Paesaggi di Donna (Milan 1965).

[53] G. Lörinczy, New York, New York (Budapest 1972).

[54] O. Steinert, Subjektive Fotografie (Bonn 1952).

[55] O. Steinert, Subjektive Fotografie 2 (Bonn 1955).

[56] In the introduction to the first Almanach fotografiki polskiej, Zbigniew Pękosławski wrote: “The arrangement of the photographs in the almanac is not accidental: the sets of neighbouring photographs were thought through to achieve an additional artistic effect, and often also an intellectual effect. When viewing the pairs of photos, it is worth pondering the reasons for their association. They will typically be artistic considerations, for example affiliation of textures and qualities, striking use of contrast, or the like. But we will also find anecdotal links, philosophical reflections, or for a change, a jocular or grotesque element.” Z. Pękosławski, introduction, Almanach fotografiki polskiej 1959 (Almanac of Polish photography 1959) (Warsaw 1959).

[57] An immediate derivative of Fotografika, and confirmation of its innovative character, was Hartwig’s small booklet published in Prague as the twenty-eighth volume in the series Artistic Photography. It contained a number of the same photos and shared a similar kaleidoscopic atmosphere. Publication in this series, which had previously featured such masters of the photographic art as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Nadar, Werner Bischof, Paul Strand, Brassaï and Alexander Rodchenko, must have given Hartwig particular satisfaction. See Z. Pękosławski, Edward Hartwig (Prague 1966).

[58] E. Hartwig, Moja ziemia (My land) (Warsaw 1962).

[59] Hartwig, “Olśnienia.”

[60] See A. Zieliński, ed., Góry wołają. Wędrówka z obiektywem od Olzy po Czeremosz (The mountains call: Travels with a lens from the Olza to the Cheremosh) (Lwów 1939).

[61] B. Bałuk & S. Bałuk, eds., Cztery pory roku (The four seasons) (Warsaw 1955).

[62] Hartwig, Moja ziemia, p. 5.

[63] K. Michałowski, Akropol (Acropolis) (Warsaw 1964).

[64] Hartwig photographed the Acropolis during a stay in Greece connected with an exhibition of his.

[65] In the 1960s, Hartwig worked on an album devoted to Yugoslavia, at the invitation of a local publisher, but the work was ultimately never published. See E. Hartwig, “Tematy same do mnie przychodzą” (Themes come to me on their own), Magazyn Gazety 1997 no. 17, p. 24.

[66] E. Hartwig, Kulisy teatru (Backstage) (Warsaw 1969). The preparations for this publication lasted nearly ten years. An announcement of a planned album with theatre photographs was placed on the jacket flap of the first edition of Fotografika. The book was released in three editions (1969, 1974 and 1983).

[67] In this sense Kulisy teatru is proof of how unusually prolific Hartwig was. From photos made in the wings (as it were) of his routine, gainful employment, a full-fledged work was created, intended to reveal this field of the photographer’s activity, yielding nothing in its autonomy and creativity to Fotografika (which in any event contained a series of shots from the artist’s work at theatres).

[68] Wydawnictwo Arkady published ambitious photographic albums in this format in the 1960s. See A. Bogusz & A. Chojnacka, Barwy i rytmy Śląska (Colours and rhythms of Silesia) (Warsaw 1969); E. Kupiecki, Warszawa. Krajobraz i architektura (Warsaw: Landscape and architecture) (Warsaw 1963).

[69] See E. Steichen, The Family of Man, exhibition catalogue (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955).

[70] See T. Mościcki, “Nowe światy starego mistrza” (New worlds of an old master), Teatr 2003 no. 12, p. 69.

[71] E. Hartwig, Tematy fotograficzne (Photographic themes) (Warsaw 1978).

[72] E. Hartwig, Wariacje fotograficzne (Photographic variations) (Warsaw 1978).

[73] Hartwig, “Psy czy koty?”

[74] Ibid.

[75] E. Hartwig, Kwiaty ojczystej ziemi (Flowers of the native land) (Warsaw 1983).

[76] The selection of poems was made by Ludmiła Marjańska.

[77] Her literary introductions to the albums were also intended to impart an artistic expression to the whole.

[78] In this sense Hartwig was an engaged heir of Bułhak’s efforts.

[79] E. Hartwig, Polska Edwarda Hartwiga (Edward Hartwig’s Poland) (Warsaw 1995).

[80] See E. Hartwig, Lublin i okolice. Wspomnienie (Lublin and surroundings: Recollections) (Lublin 1997); E. Hartwig, Mój Kazimierz (My Kazimierz) (Lublin 1998).

[81] E. Hartwig, Wierzby (Willows) (Warsaw 1989).

[82] E. Hartwig, Halny (Mountain wind) (Lublin 1999).

[83] Wierzby, with its black cover of synthetic canvas and raw offset printing on unrefined coated paper, is an interesting document of the decline of Polish printing in the waning of the communist era. But this rawness, once again, does not harm the author’s works, which are expressive, contrasting, and graphic in nature.

[84] E. Hartwig, “Wierzby i fotografia” (Willows and photography), interview by P. Białek, Stolica 1989 no. 33, p. 21.

[85] Bułhak, Fotografika, pp. 150–157.

[86] See “Ciekawa fotografia” (Interesting photography), Słowo Ludu, 28 February 1961; K. Łyczywek, “Fotografika Edwarda Hartwiga” (Edward Hartwig’s photographics), Kurier Szczeciński, 8 April 1973.

[87] See “Na warsztacie—teatr, Kraków, Pieniny i… Akropol” (At the studio: Theatre, Kraków, the Pieniny, and the Acropolis), Kurier Lubelski, 23 March 1963.

[88] Hartwig, “Hartwig o sobie,” p. 10.

[89] According to Bułhak, the distinction between applied and artistic photography consisted among other things in the method of treatment of the negative: “Now the negative has returned to its proper, more modest role, becoming only a point of departure for further interpretation of the image, personal and artistic.” Bułhak, Fotografika, p. 169.