After Instagram removed and restricted posts related to the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem during the escalated military conflict in the Middle East this summer, Facebook employees quickly apologized for what they had done. Based on the correspondence of the company’s employees, the censorship was carried out on “enforcement errors,” since several banned organizations have in their titles the term “Al-Aqsa” (الأقصى). At the same time, hundreds of photos were flooding Instagram at the location of Gaza City, testifying to the ongoing violence. Among those taken by people on the ground, there are also photographs published for propaganda purposes. Among them, pictures that represent the incredible cruelty and horrors of war.

A striking example is a picture in which a child washes the floor from fleshy blood. Unfortunately, I have not found the source of this photograph which may also indicate a manipulative component of this image. It turns out that the documentary nature of the picture is not as essential as a strong image, which is supposedly capable of awakening emotions in a person—from aggression to humanism and back.

There are many examples of manipulation of images in contemporary media history—publication of such brutal and violent content is one of them. For example, photographs from some places are replaced by others, like the “battle of words and images” that occurred during the war in Donbas. These kinds of posts come not only from media accounts or bots but also from real people who post unverified or shocking content because they want to draw attention to problems in their regions, or to show their political confidence.

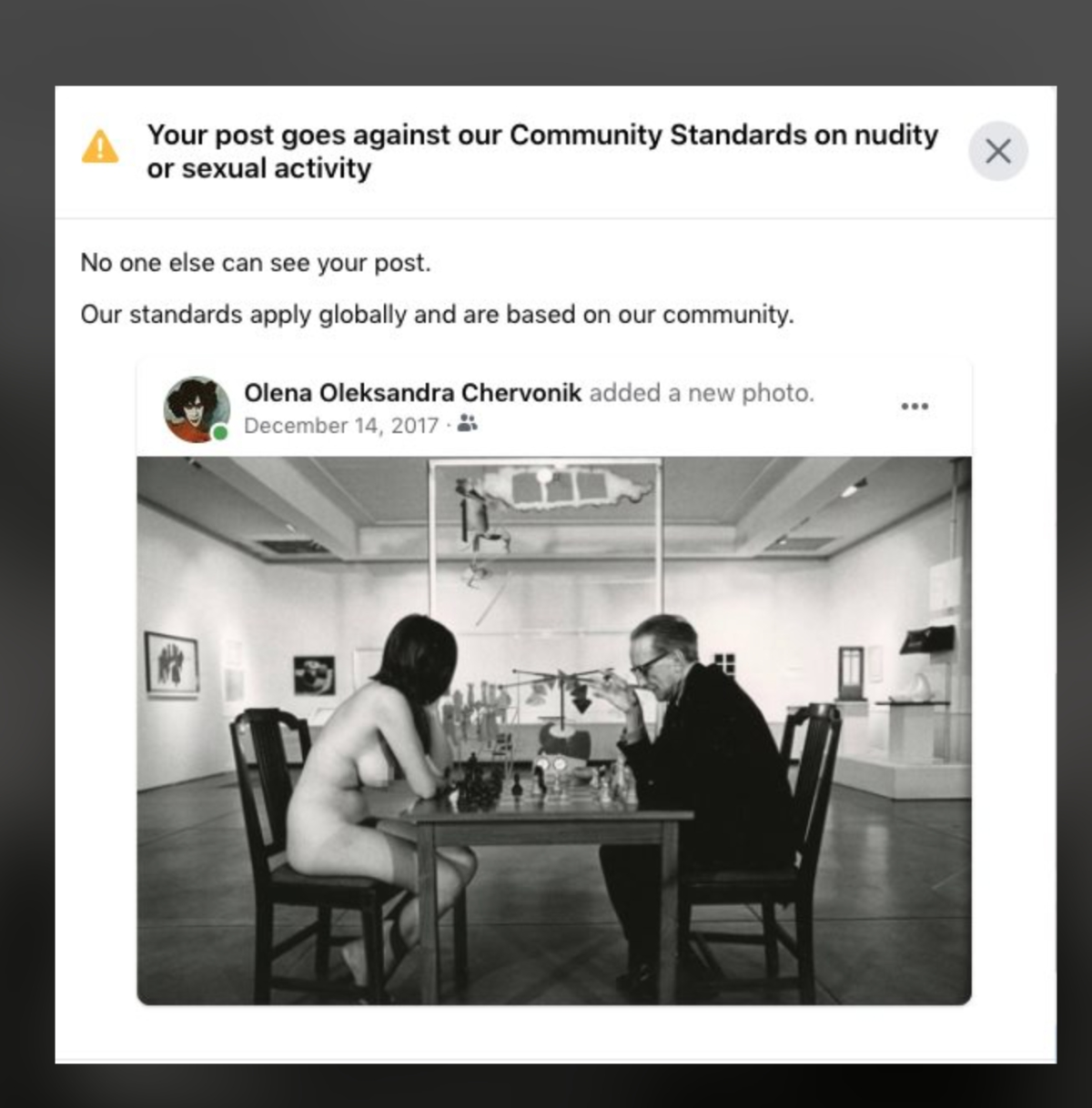

In the fight against manipulation and propaganda, as well as for protecting children and teenagers from low-quality content, Instagram took on the responsibility of creating a filter and warning people about violence or any kind of horrific content. However, it is ironic that Instagram, which has functionally included in its algorithm the “sensitivity” function, which involves using a blur filter on images of a sexual or violent nature, does not apply this algorithm to these aforementioned images. Nevertheless, I can give many examples of when this filter was used in my feed. For example, my colleague from Moscow, who switched from journalism to astrology, made a post with a voice of violence from the protests in Russia this summer. Over this sound, she adds a text where she asks the police not to murder people in the streets: she asks for non-violence. Nevertheless, Instagram immediately blurred this post, even though it was against the violence. Alternatively, for example, posts by young activists, who promote animal protection, are also censored. Paradoxically, posts in defense against a different form of violence are censored. Still, at the same time, direct violence, blood, death, and portraits of rapists remain in the public domain without any censorship. These are just a few examples of such censorship. Many artists and photographers face this problem, publishing their artwork aimed at criticizing violence, or dedicated to the topic of the body politics, femininity, feminism, LGBTQIA+ content, advocating for abortion, etc. Again, many photographs of violence, war, real pornography, and death still exist in the public domain. Users claim their content to be “evidence” of violence, which means they have an excuse for what they broadcast.

When I interviewed war correspondents this summer, I asked them a question: why do people post other people’s photos of violence and aggression? One of my interlocutors argued that in this way they want to protect themselves, attract public attention to the violence and tyranny, and in fact, the most terrible image is the strongest cry and prayer for help. As if the cruelty in the photograph creates fear and aggression, thanks to which people begin to act. So, I argue, is there a hierarchy of horrible images? What is “sensitive content”, or do we rather love our in-sensitivity? And what is more important, does our sensibility need to be protected by anyone?

In her book The Monarchy of Fear (2018), Philosopher and Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago, Martha Nussbaum argues that political choices and decisions are always based on emotion. I can add that today we’re even more vulnerable. I conducted my interviews mainly with female photographers, as I was interested in the role of gender in work as a war photographer. I also asked about self-censorship. It turned out that all the respondents said that they filmed even the most violent shots, but they chose never to publish them. Why did they take them, despite the fact that they knew they would never show anyone? On the one hand, it’s because of protection. For example, photographer Heidi Levine mentioned that she uses the camera to protect herself from that terrible reality, and then can show the pictures in court for justice if needed. Perhaps it was the same argument that was used by Lee Miller, who shot the horrors of World War II for Vogue magazine, and who could not publish and show the enormity of the images to anyone. After the war, she stopped taking pictures altogether and kept the photographs from prying eyes. Following all these examples, I can’t say that all these women photographers lost their sensibility, on the contrary, it testifies to the powerlessness of a person before the tragedy of which they are witnesses.

In an interview, documentary photographer Aline Manukyan, who filmed the war in Lebanon from 1984-1990, said that she felt the impossibility of sympathy at some point. In 1989, she came to Armenia to film a story about how people were rebuilding their lives after the earthquake. However, she realized that she “needed a big dose of tragedy to feel anything.” She compared the situation to taking drugs when after each intake, the thirst to increase the dose increases.

But if photographers are witnesses, newspaper readers and social media users do not always see the events with their own eyes, even if they watch the live broadcast of the tragic events that happened “in that moment”. Why do the readers want to see the pain exactly at that tragic moment? Does it really help us to develop empathy, and/or be ready to act?

It is difficult to calmly look at the image of a crying child or a mother who lost her family in war. Today, contemporary media is full of visual documentary evidence of wars: violence, hatred, and tyranny have taken different forms and have firmly entered our lives. We see this in the movies, in the mass media. We live in an era of different kinds of wars. Furthermore, even if we do not face them personally, it still has a tremendous visual experience. Nevertheless, does this mean that all this makes us more sensual and humane? Or are we just used to violence and did not notice it, even on our social media feed?

The issue of visibility is crucial here. Symbolic partial censorship of violence is just a corporate performance “protecting” its users from inappropriate content. Removing access or partially censoring it does not solve the presence or absence of violence in our lives. Things like this can lead to partial blindness when we, like moles, lose sight of ourselves in our underground disciplinary tunnels. So, we need to ask the question, not what we see, but why can we not see something? Do we limit ourselves from violence, thereby fencing ourselves off from uncomfortable topics?

In A Passion of Ignorance (2020), Slovenian philosopher, sociologist, and legal theorist Renata Salecl explores the human desire for ignorance. She argues that this desire is not new for culture, but what is radical compared to our past is that “people are united not in closing their eyes to the truth but rather by their ignorance of what the truth is”.

In other words, the creation of protective filters against violence speaks of a desire not to take responsibility for decisions and opinions, and ignoring the violence allows a person not to act against it. If a person’s decision is dictated by his fear of facing a problem and social insecurity, then corporations, in turn, use filters for political and commercial manipulations. Today, the Internet and social networks are the largest data and visual archives which are changing in real-time. These archives are replenished with a variety of materials, both due to the activity of the users themselves, and thanks to special political technologies. Among the biggest challenges of our time are two issues: content curation, mentioned by Michael Bhaskar in his book Curation: The Power Of Selection In A World Of Excess (2016), and the idea of a ‘new memory ecology’, used by Andrew Hoskins in his article Media, Memory, Metaphor: Remembering And The Connective Turn (2011). How do technologies and the Internet affect our memory and the visual culture of the time? For example, by searching the Google image archive, it is easy to identify certain visual patterns that exist now in media and the Internet. The search function and other tools on the site are built by logging and analyzing individual and popular requests. Search results may vary from time to time, but mostly the image will be a slowly evolving picture of internet users’ interest in a given topic. Through algorithms, they decide which content is useful and relevant to a person, and which is not. These preferences are formed not only on the basis of unique human needs but also on the basis of the company’s internal policy and its loyalty to partners. That is, a search query about the same military conflict, even from the same computer, but in opposite countries, might be different.

On the one hand, photography will never give a complete picture of what is happening, and it will never give an understanding of how it was in real life. Therefore, it is easy to manipulate, generalizing the information shown in the picture. On the other hand, photography can create an image that can help us feel the experience and immerse us in the circumstances we have never been. Authors can record events, but the media will exploit emotions—fear and hate.

The paradox of today’s new sensibility lies in the fear of truth and reality. However, what we should be afraid of does not cause our emotions. We silently consume violence as content. We silently agree when this violence is partially censored for the appearance of working in an ethical field. But does it give us these coveted ethics?

Once American writer Susan Sontag asked how we feel when we look at someone else’s suffering. Now the answer is probably pretty obvious. In response to this question, philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler noted people’s selective compassion. But, now we risk avoiding reality altogether, without a choice of who receives our empathy, or how we try to sort out conflicts, and make commitments to advocate civil rights. And the main thing is to know in advance what emotions we are expected to experience when scrolling a news feed or reading entertainment content, or perhaps what is more important—to not feel anything.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Index | Kateryna Iakovlenko |