Ewa Borysiewicz: I have been thinking about this a lot myself, and this is one of the reasons I wanted to talk with you, since it’s difficult to find an answer alone – the art world is changing, and it seems to me that these changes are not for the better. The Polish art world is becoming more and more ossified, more conservative, there is a huge and painful institutional turn to the right. On the other hand, one can observe a commercialization – to a caricatural degree even – of artistic position. I was wondering how you act and work, in the art field in the face of these processes, is there a way not to give in to these processes. Have you managed to find a path of your own in this situation, or are you still looking for one?

Katarzyna Różniak-Szabelska: It is true that with the takeover of more public institutions by the right-wing government, we have found ourselves in a trap in which the art market and commercial galleries are sometimes presented as the alternative. And it would be a dangerous situation to let the logic of market-driven entities exclusively decide the direction of art. As for me personally, when I started to work in the field of art I had to go through various places. I started in a commercial gallery, knowing however that art dealing won’t be a satisfactory path for someone with beliefs like my own. Later, I worked in the Collection Department of the University of Arts in Poznan, where in turn I was surprised by its extremely conservative structure.

For the past three years I have been a curator at the Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok, which is a municipal institution. This position seems to provide opportunities to resist both the commercialization of art and right-wing pressures. Because so far – at least at the level of institutional or municipal decisions – Arsenal remains unaffected by the conservative turn. Which is not to say that we don’t face it in a broader context.

I understand that for the institution, exposure to the conservative tendencies is discernible not so much in the administrative spheres, but in the wider field of public debate.

Yes. That, in any case, is my experience. We are forced to deal with the backlash from the right-wing press and conservative groups. Their actions are calculated to intimidate contemporary art institutions and their employees and are often well organized. My first such experience was working with Matthew Post (as Post Brothers) on the exhibition “In the Beginning was the Deed!”[1]. The project took as its starting point the history of insurrectionary anarchism in Bialystok around the 1905 revolution. With statements both anti-capitalist and allied to the LGBTQ+ movements, and with a focus on radical strategies of struggle, it provoked strong opposition from conservative circles. Right-wing organizations filed notices of possible crime with the prosecutor’s office, so we had to testify before the police. The right-wing media waged a long and stressful campaign against the institution. In consequence, the gallery employees received offensive phone calls and faced a serious social media crisis. Fearing physical attacks, we had to hire additional security, and eventually the city sent a police patrol that circled the gallery every hour. Quite an absurd performance for a show dealing with police violence!

This reaction was centered around the work of Karol Radziszewski?

That’s correct. The historical context of this exhibition emerged from the fact that at the beginning of the 20th century, Bialystok – a city of workers, undergoing merciless modernization – gave birth to the most radical fractions of anarchism worldwide, including groups like „Chernoe Znamia”, that believed in violence as the only way to fight injustice. Therefore, the need of the oppressed for revenge, as well as their agency, were important dilemmas problematized in the show. That’s why, together with Matthew, we wanted to present “Fag Fighters” by Karol Radziszewski. The project, started in 2007, depicts a fictional gay guerilla in a pink balaclava, humorously embodying right-wing fears and stereotypical perceptions about the transgressions of the gay community, which, according to some right-wing fantasies, carry out sexual assaults on straight men. For the show at Arsenal, the artist – originally from this city – updated the installation with documentation of assaults by both hooligans and city residents that occurred during the first Pride March in Bialystok in 2019. This footage was integrated into the work in a way thatsuggested that these attackers would bethe targets of the Fag Fighters. On the one hand, the work gives a lot of power and agency to the excluded group. On the other hand, in a laboratory space of an art institution, the need for revenge of the oppressed community could also be worked through without embodying it in real life, allowing difficult emotions to be processed and understood.

Obviously it is difficult to function in a reality that negates leftist values, but it was also a very constructive experience, one that showed that contemporary art spaces can be important not only for artists or a narrow milieu of art professionals, but also for the city and its inhabitants, even more so on the periphery. We received thanks from young people who were afraid to walk around the city on their own since the march. They appreciated our courage for being so blunt about discrimination in Bialystok. It made us realize just how little systemic support is available here, and how big it automatically (and quite unexpectedly) made the role we suddenly occupied in the city’s public debate.

You were able to take a stand as an institution, but I imagine the backlash was also felt personally by the individual members of Arsenal’s team.

Yes. It can be said that resisting the conservative turn was a challenge for the whole team in this case, but it is worth noting at the same time that we were enabled to do so by working from the position of a city institution. However, I also think a lot in this context about the phenomenon of self-censorship. Current debates in Poland or reports, such as those prepared by AICA[2], deal with events that have taken place publicly. Meanwhile, I think every institutional director or curator, after leading a team through such trauma, thinks twice before taking on another “controversial” project, and asks themselves whether they have the strength to go through all these consequences again, or whether they have the right to burden their employees in this way. We are still lacking truly efficient inter-institutional support networks or effective procedures for acting in emergencies like these. I guess we will never know the extent of intimidation and its effects on institutional programming.

But just so we’re clear: I don’t want to idealize public institutions. For sure, they are not free of hierarchy or the problems that result from these structures. But at some point, you have to choose the position from which you’re going to act. Discussions about the non-institutional organization of art spaces may sound attractive, but often overlook the financial aspect of such activities. To be honest, with no other type of income or economic security, I find it hard to imagine working totally outside the existing system. So, I must choose to believe that public institutions with stable funding and the ability to reach a wide audience still offer opportunities to influence their environment and public debate through art. As long as we remember that their internal practices should be aligned with the declared values.

Looking at the exhibitions you’ve put together – I’m referring to “Deschool!”, the solo show of Alicja Rogalska, or the aforementioned „In the Beginning Was the Deed!” – they are attempts to relate to the place in which they are located, and secondly, and perhaps more importantly, in their very core they have some kind of potential for change outside the gallery space. When you plan an exhibition, do you have any specific expectations about the outcome?

I’d like to answer your question about locality first. Indeed, this has been a key reference for my work in Bialystok. Podlasie’s peripheral location, in the context of a borderland, of its historical multiculturalism (in opposition to the contemporary popularity of nationalist sentiments in the region), revolutionary history or its proximity to the last primeval forest in Europe, makes it a place from which we can learn a lot. I believe an art institution can and should be a place that generates knowledge based on various local experiences.

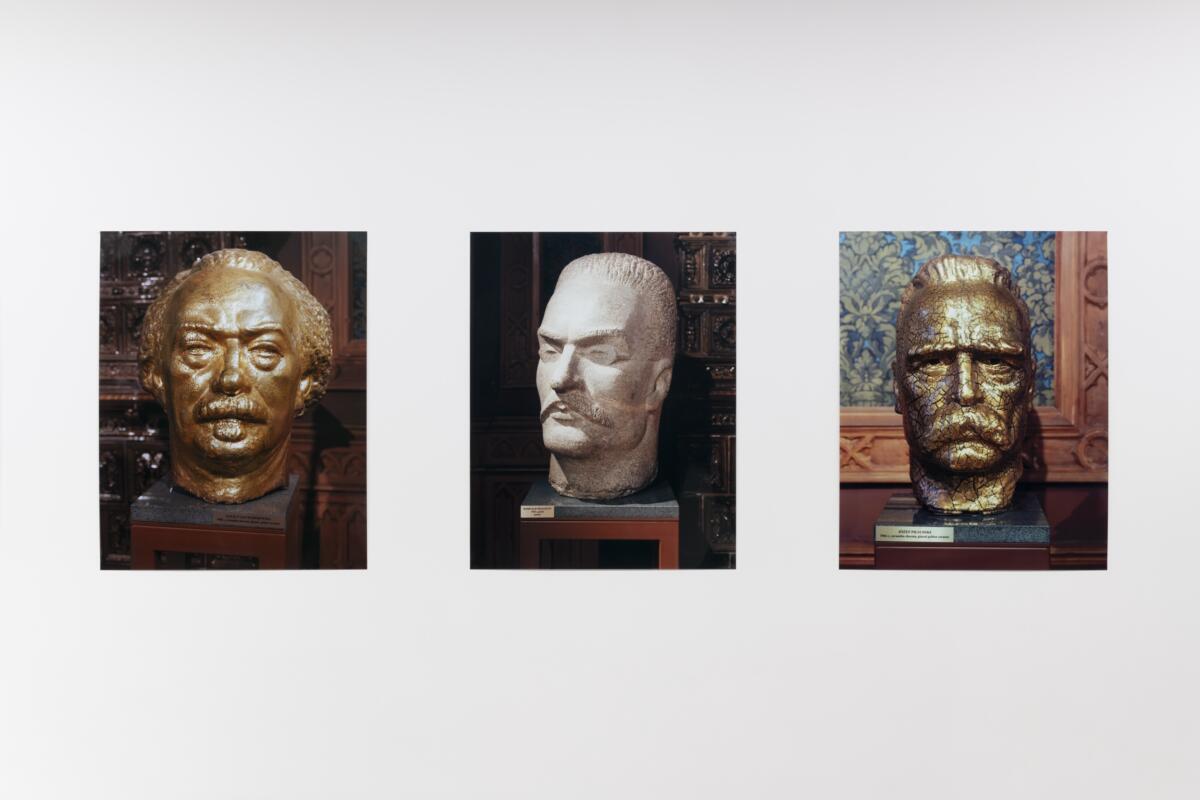

Constructing local histories and identities has been recently addressed in the exhibition of a Czech photographic duo Lukáš Jasanský and Martin Polák[3]. In 2019, they produced a series of photographs resulting from an accidental visit to the Alfons Karny Sculpture Museum in Bialystok, an institution that presents the artistic oeuvre of the portrait sculptor who was born here. The museum features his “Gallery of Great Poles”.

One of the most interesting things I’ve read about the relationship between historical multiculturalism and contemporary nationalism in this city is a text by local sociologist Katarzyna Sztop-Rutkowska, who used the term “folder multiculturalism”. According to her, though in every tourist folder the statement: “Białystok was and is a multicultural city” appears, the common story of Bialystok still lacks specific figures or events that would clearly describe (or represent)this multiculturalism. Both the results of surveys of Bialystok residents’, regarding their consciousness and the way official histories of the city are written or depicted in public space, marginalize the stories of the city’s non-Polish residents. The same goes for most public institutions. The exclusive subject of the project entitled “J/P/K Jasanský Polák Karny”, are frontally photographed busts from the Alfons Karny Museum collection. But while reminiscent of records from a museum inventory, the series maintains an aura of objectivity, while also presenting humorous elements and the artists’ distance from heroic narratives. The presentation of this project in Bialystok, however, was also meant to question the construction of local identity and the role that institutions play in this process. How does a city, created by Jews, Poles, Belarussians, Russians, Germans and Ukrainians, decide to set up a museum with a “Gallery of Great Poles”?! And how does this translate into contemporary attitudes towards people of other nationalities?

Art can critique stagnant narratives, but it can also build representations of overlooked histories, pointing to their potential for creating a better future. Within “In the Beginning Was the Deed!” Matt and I had the opportunity to restore the revolutionary history of the city. The beginning of the 20th century is – in the official narrative of the city and the local Historical Museum – a period of prosperity and time of industrial boon. Nowhere is there any mention of the mass multicultural labor movements active in Bialystok at the time. For the first time, through the project, local activists were able to combine this history with their present-day struggles. We have initiated research into the as-yet unwritten chapters of the history of Bialystok anarchism, calling at the same time for global solidarity. And I can see this from the reception of our exhibitions, that in those moments when we touch upon local problems and are not afraid to talk about them, we have the strongest impact on the audience closest to us.

Then again, I understand “the local” also in the broader context of Central and Eastern Europe. This is also why I always imagined working here at some point, even before any real opportunity ever came up. Thanks to Monika Szewczyk’s consistent strategy of cooperation with artists from Ukraine and Belarus, Arsenal is a valued and recognized institution in these countries and establishing further relations is easier. Last year I was able to organize an exhibition of the young Ukrainian artists and filmmakers, Yarema Malshchuk and Roman Khimei[4], which was dedicated to relations between different generations of Ukrainian citizens and residents of the various regions of the country. An undertaking even more important in the context of the influx of Ukrainian newcomers, who were forced to flee to Poland after the full-scale Russian invasion commenced.

The courage to address issues present in one’s vicinity reminds me also of one project you organized in the city space, I mean the performance by Public Movement in May 2022[5].

I like going back to this day. It consisted of subjects that organize our conversation: locality, the agency of art, and collectivity. In fact, Public Movement call themselves a “collective research body”. Their day-long action was put together by Dana Yahalomi and Nir Shauloff, after their visit to Bialystok, during which we spoke with city guides, local activists and migration researchers. “One Day” was a result of this investigation. Multiple performances activated the city’s historical axis, drawing attention to its existing memorials and proposing new forms of commemoration in public space. At the Monument to the Heroes of the Bialystok Region – a place of importance for right-wing circles, standing on the grounds of the former Jewish cemetery – adorned today with the words “GOD”, “HONOR”, “HOMELAND” and “INDEPENDENCE”, together with the local youth, the performers created the word “FRAGILITY” out of jute, with which they then shared as they traversed the city space. The day ended with it being burned against the backdrop of Bialystok’s main cathedral.

However, the main part of the action was centered around the humanitarian crisis occurring on the Polish-Belarussian border[6] and the welcoming of Ukrainian newcomers on the Polish-Ukrainian border. In the main square of the city, members of Public Movement were recreating choreographies of evacuation: of moving bodies of the strangers, lifting them, dragging, holding, supporting and caring for them. The audience became an integral part of the process, as both the object and the subject of these activities, protecting each other’s bodies. The action involved both activists from the Polish-Belarusian border and people from Ukraine who had recently settled in the city. They all brought their own experiences. This event was particularly important because the humanitarian crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border is taking place just 50 kilometers from Bialystok, and life in the city is flowing as if nothing has changed. Public Movement’s action made the crisis visible in the heart of the city. That day, art became a tool to trigger empathy, flowing from the surprising knowledge about acting together in an emergency that human bodies seemed to possess independently of our awareness. Confronting oneself with these instinctive reactions of one’s own body was a very powerful experience, evoking honest and deep responses. The artists wrote that Bialystok was performing its alternative political self in the streets that day. Some call that a “pre-enactment”. Once again, questions were also raised about existing representations of history and the values they represent in public space, and alternative forms, words, and actions were proposed, linking them to the most acute contemporary crisis, at the core of which are today’s reactions to non-European newcomers.

Operating in the field of art in the context of such a cruel humanitarian crisis is particularly difficult for me. On the one hand, we cannot not talk about it. And on the other hand, each time we take up this subject it too easily raises the risk of capitalizing on suffering, which we try to avoid by focusing on collective processes rather than by producing objects.

Which would not change much eventually, the problem gets „passed on” in an easily consumable, static form. I would like to ask you about how you imagine or define the agency of art in these circumstances? Or the agency of the exhibition as a medium in general?

I enjoy working with artists who initiate and engage in communal, collective processes, just like Alicja Rogalska, an artist from the region (born in the village of Wszerzecz near Lomza). In “Instead of Sighing We Turn to Singing”[7], her recent exhibition at Arsenal, we have presented her works created within the last decade in cooperation with different communities around the world. Most of them were connected by singing – as a way of telling stories and reclaiming agency. The Georgian Polyphonic Choir, the Women’s Choir from the Hungarian village of Kartal, members of the Union of Street Musicians in Jakarta and the folk singing group Broniowianki from Mazovia, who have collaborated with Alicja over the years, sing about the injustices they face today – inequality, economic exploitation, and difficult living conditions. The processes initiated by the artist help in the search for the collective voice of specific communities, often using traditional folk songs with new, modernized lyrics that have been created together. Alicja also took part in the 2022 residency organized by us in cooperation with the House of Culture and Nature in Teremiski[8], near Białowieża, where she met activists working on the Polish-Belarussian border. Together they prepared an evening of caroling performed during the opening of the exhibition. In the context of the humanitarian crisis, we sung regional carols that mention hospitality and exchanged personal stories about Christmas generosity. I felt that again, we managed to create an authentic moment. And this is one possible answer to your first question about ways to avoid the commercialization of art and the role of the artist – to support not only the production of art objects, but the facilitation of these kinds of collective processes and encounters, forging new bonds, and encouraging commune. Such activities also reinforce the agency of art which then directly affects the participants in the art processes, enabling them to understand that their problems are systemic, and they can take collective action to try to combat them. But I also don’t think it’s the only right direction for art… I still believe in art’s role in storytelling and creating meanings that organize or influence the way we think of the world when we encounter and experience it.

Regarding the exhibition as a medium: I like to consider an exhibition as a kind of process happening over time, where the outcome is not given in advance. As something that is not a closed structure, where everything has already happened at the moment of the official opening.

This was the case of the „Deschool!”[9] exhibition, from what I remember. On the one hand, you outlined a concrete issue and worked on the core subject of the show, that the artists addressed. On the other hand, through the duration of the show, a weekly collective activity took place that proposed alternative modes of learning and discussed them together with the public.

Exactly. This exhibition presented works based on artistic research on the problems of higher education in the arts in the region. The show featured works by the duo Little Warsaw, Martina Smutná, Lada Nakonechna, R.E.P., and Weronika Zalewska, among others. They talked about conservative, hierarchical structures and ways of teaching, patriarchy, the destructive and exhausting power of competition and individualism among students, the commercialization of art education, its lack of responsiveness to contemporary problems or learning from historical student revolts. At the same time, the exhibition showcased art collectives using alternative educational methods as part of their practices. The Nowolipie Group, Kem Collective, Problem Collective, and Mothers ArtLovers were not only presented in the exhibition, but also activated it on a weekly basis by implementing their experimental alternative educational strategies based on non-hierarchy, collectivity, community processes, fun, and pleasure. Thanks to that we could co-create the whole project with the artists and audience.

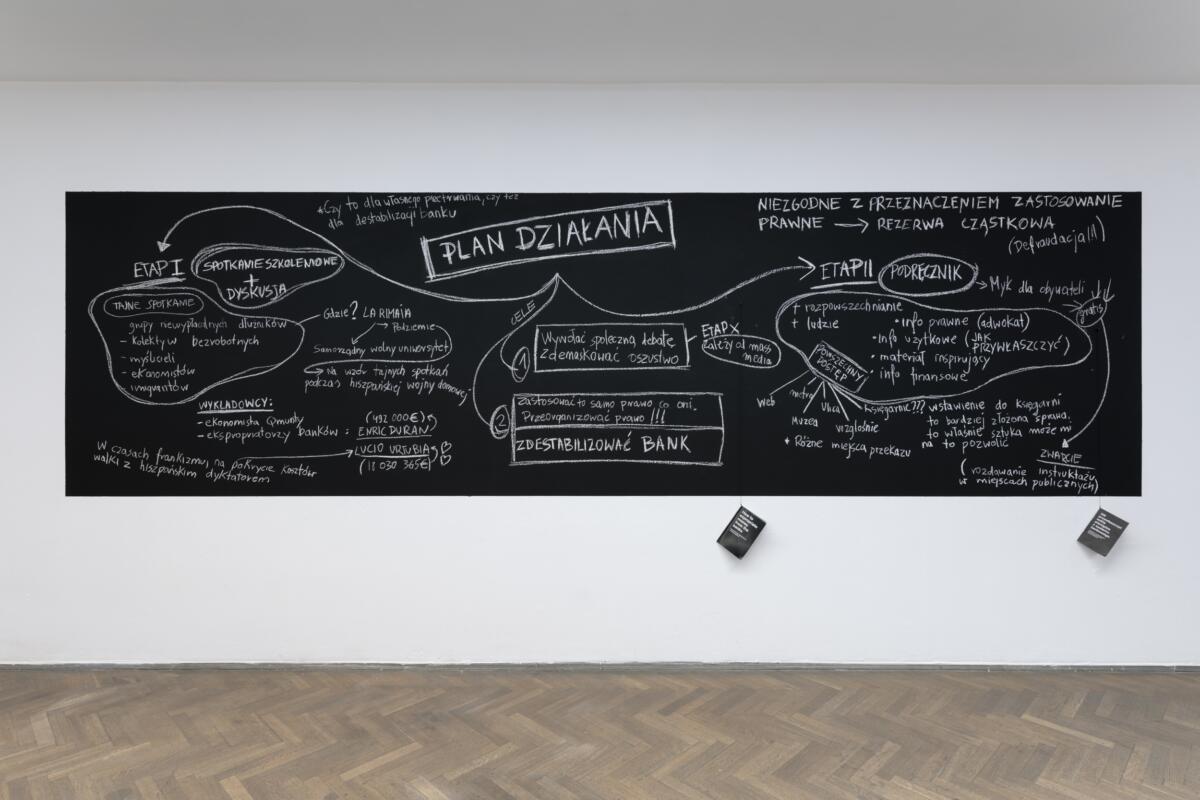

Together with Post Brothers we worked in a similar fashion for “In the Beginning Was the Deed!”, where too, in the center of the exhibition, we created a common space named the „revolutionary birzha” („revolutionary exchange”). It was a reference to a historical space on Suraska Street in Bialystok, where workers used to meet to exchange literature, discuss ideas and sing revolutionary songs. The „birzha” in the exhibition space was filled with materials we found about Białystok’s anarchist past, which the public could copy and learn from. It was also a meeting space where we could connect historical events with the contemporary political reality. The community created through this process prepared a walk through revolutionary Bialystok for the finissage of the show.

But, while I believe that focusing on processes – including from the perspective of the exhibition as medium – strengthens the agency of art, and to some extent, opposes its commercialization, I also still have faith in traditional art media and the exhibition medium itself. Works rooted in artistic research or those that emphasize storytelling within described projects were proof of this. I also remember, for example, that Anna Hulačová’s “Alienbees, save us please!”[10] was appreciated by the Youth Climate Strike in Bialystok for the complex meanings and concrete ecological narratives it engaged with in the most extraordinary and captivating forms.

You have a very intense year behind you, but I suppose that encounters like those described motivate you to continue working.

Yes, moments of establishing authentic relationships within artistic processes are very motivating for me. I believe art is a place for collective conversation, reflection on the state of things and a space where you can discover ways in which the world can be changed. My other source of support comes from the freedom that the institution and its director Monika Szewczyk gives me in creating shows, the engagement of the audience and encouragement from friends who make up this small but very interesting artistic community of Podlasie. I am deeply grateful to my ever-supporting husband and critically-engaged artist Tytus Szabelski-Różniak, who has a highly reliable ethical compass, to Matthew Post, the curator and enthusiast who initiated “In the Beginning Was the Deed!” and invited me to co-create the project, to the great artist and caring person Iza Tarasewicz and perhaps our closest friend, curator Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew. They all genuinely care about both the region and art and are always willing to engage in new ventures. I can always count on their honest and insightful feedback.

I wanted to ask you about how you see the role of the curator, but I think you’ve already answered that question to a certain degree. It seems to me that the curator for you is not such a separate genius figure who orchestrates from behind the scenes. You talk quite candidly about the fact that you discuss your ideas with friends or people you trust. I understand that in the same way you talk to artists, you treat them as partners.

Of course, and for me it has never been any different. An exhibition is a conversation between many people, objects, conditions, discourses and processes, with whom the curator cooperates and mediates. I would be surprised to see a different attitude from curators of my generation. It’s fundamental to work with the artists on an equal basis, and a partnership with the gallery team is also vital. It’s necessary to remember that an exhibition is not made by only the efforts of artists and curators – but that there’s a lot more people involved. If I may, I would like to mention at least some of those whose names rarely appear in public. At Arsenal, it is particularly important for me to work with the technical department. I have never operated on a budget that would allow me to hire an exhibition architect, so most of the solutions are worked out in long discussions between the artists and technicians Maciej Zaniewski and Kacper Gorysz. I would also like to mention Jarosław Trojan, who recently passed away and is going to be missed by his co-workers for the years to come. He worked at the gallery for 40 years and was not only a guide for the next generation, but part of the spirit of the place. Then there is Ewa Borowska, who works on projects in the publishing department. It is thanks to her efforts that we have just released the Polish edition of a book about Bialystok anarchists, after a long and thoughtful translation process[11]. There is Gabriela Owdziej from the PR department, Justyna Kolodko-Bietkal, Iza Liżewska, and Katarzyna Kida from the education department, as well as the drivers, people working as coordinators (I am especially grateful for the help of Ewa Chacianowska), writing grants, accounting, and exhibition guides: all of them co-create or facilitate the creation of exhibitions at Arsenal, and mediate existing ones.

Yes, I agree with you. Physical work is often less valued as compared to, let’s say, „creative” activities, or work with ideas. Did you also learn lessons from these exhibitions for yourself personally, did they also affect you in a certain way? How and if working with artists influences you?

I learn a great deal with each exhibition. I guess we all work through ourselves in one way or another in the art field and the subjects of exhibitions I work on are usually also personal for me. But if I had to point to one specific example from recent months it would probably be Martina Smutná’s criticism of the exhausting competitiveness and overproduction in the art field. Her paintings dealing with the subject, which we presented during “Deschool!”, were highly relatable to me at the time. I realized that I needed to work less intensively and spend more time taking care of myself and my human and non-human loved ones (hello to Tytus and to our dog Ściółka!). I am now trying to put that into practice.

What are you working on in 2023? What are you looking forward to?

This year I am mainly working on a group exhibition, which opens on the last day of June in the historic building of the former Power Plant in Bialystok. It will present contemporary works relating to the modernization of the countryside: the industrialization of agriculture, electrification, and the contemporary and future consequences of these processes. It is important that the core narrative of the show will mainly include the perspective of artists originating from the so-called “periphery”, often referring to the microhistories of their own families. We plan to juxtapose these accounts with the official historical narrative that organizes our memory of these processes. These will also be contrasted with contemporary artistic practices seeking inspiration in pre-modern customs in the region. I am also looking forward to the performance program planned as part of this project, which is to be co-created with local artists from the Podlasie region and Białowieża Forest. Performers are going to create a welcoming space for visitors.

In addition, I will also be working on two solo exhibitions of female artists representing minority perspectives in Poland. As part of the celebration of the 80th anniversary of the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising, we will open an exhibition by Zuzanna Hertzberg, dedicated to herstories of Jewish women fighters. At the same time, we have scheduled a solo exhibition of Marta Romankiv, who was born in Lviv. Marta has been working on the issue of newcomers’ rights in Poland for years. Her work, based on social experiments in the field of art, is, in my opinion, one of the most authentic examples of agency in Polish art in recent years.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

[1] In the Beginning was the Deed!, Arsenał Gallery, Białystok, 06.08.2021 – 23.09.2021

[2]See: https://teatrstudio.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Raport-o-cenzurze.pdf

[3] J/P/K Jasanský Polák Karny, Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok, 2.12.2022-19.01.2023

[4] Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei. So They Won’t Say We Don’t Remember, Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok

[5] Public Movement. One Day, 13.05.2022, Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok. Action was realized with the support of the Goethe Institute in Warsaw within the project When The Sun Is Low – The Shadows Are Long.

[6]Since the summer of 2021, there has been a humanitarian crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border due to illegal push-backs by the Polish Border Guard against refugees from Iraq, Afghanistan and other countries in the Middle East and Africa, among others.

[7]Alicja Rogalska, Instead of Sighing We Turn to Singing, Arsenal Gallery, Białystok, 2.12.2022-19.01.2023

[8]Dom Przyrody i Kultury, Teremiski, https://www.instagram.com/dom_przyrody_i_kultury/

[9] Deschool!, Arsenał Gallery, Białystok, 08.07.2022 – 18.08.2022

[10] Anna Hulačová. Alienbees, save us, please!, Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok, 19.11.202-10.01.2022

[11]https://galeria-arsenal.pl/images/upload/wydawnictwa/2022/BIAŁOSTOCCY_ANARCHIŚCI_1903-1908.pdf

Imprint

| Place / venue | Arsenal Gallery, Białystok |

| Website | galeria-arsenal.pl/ |

| Index | Alfons Karny Alicja Rogalska Anna Hulačová Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok Chernoe Znamia Ewa Borysiewicz Karol Radziszewski Katarzyna Różniak-Szabelska Lukáš Jasanský Martin Polák Matthew Post Post Brothers Public Movement Roman Khimei Yarema Malashchuk |