War and weapons and dead bodies and children left without parents and dictators who live in their own made-up worlds devoid of any trace of humanity. That’s mainly what has been running through my head as images, videos, or just plain texts for the past two years. Every time you think “this cannot get any worse”, it does.

Hungary is no exception to this desolate worldview, being probably one of the most restrictive countries in the European Union, especially in the fields of art and media. According to a report published in 2022 by the Artistic Freedom Initiative, artistic freedom in Hungary has been systematically suppressed by the right-wing government, resulting in (self)censorship and the migration of cultural workers to more permissive countries. The mechanisms of artistic suppression, according to the report, include federal funding being dependent on the political approval of key cultural institutions’ directors, and complex bureaucratic control of the artistic sector through FIDESZ, the ruling party.

When I visited the capital, Budapest, over a month ago, I was well aware of this situation and set the intention of only visiting independent art spaces or galleries that still had a relatively free framework, based on suggestions from friends and colleagues in the local community. However, I also wanted to see Handle With Care, an exhibition that opened mid-September last year at the Ludwig Múzeum, as the topic of caring struck me through its soft, beautiful antagonism to what was going on around.

Carefully curated by Rita Dabi-Farkas and Viktoriá Popovics, the show referred to the act of caring as something common among all human beings, whether on an individual (self-care) or a collective (for example, caring for our elders) level. On a larger scale, care has relevant global dimensions, such as care migration, which often occurs in Eastern Europe and in other economically less developed countries. Handle with Care addressed the many faces of our increasingly unstable world, where the gaps between social and economic classes are becoming wider and wider, exposing the vulnerable to new challenges and adversities. At the same time, the exhibition aimed to describe and criticize the cracks in our social and economic systems in a poetic manner, something that was reflected in the chosen artworks so well that I often had to stop and weep for a few minutes before continuing my visit. Many of the presented artistic positions touched me through their simultaneous subtlety, fragility, and strength. They made me wonder whether society will be able to finally heal itself, or rather if all these inequalities are just going to continue to deepen, leaving the affected people needing to find new ways of being even more resilient.

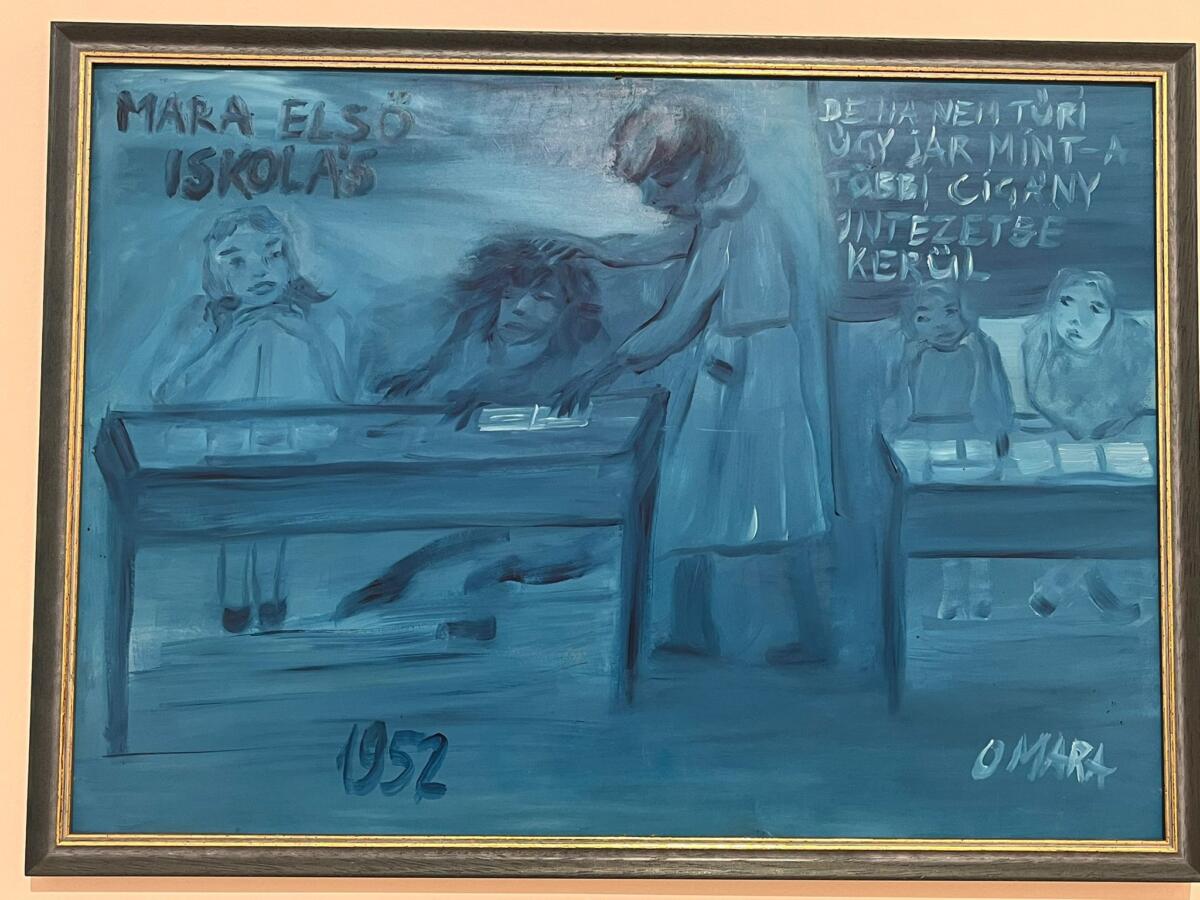

Entering the exhibition I was immediately taken by the hand by Oláh Mara’s (alias Omara) works, which led me through the whole space as an intersectional red thread connecting different sensitive topics such as racism (institutional or otherwise), social exclusion, and motherhood. Omara was a force of nature, a self-taught Romani artist who started creating in her forties, using art as a healing tool to overcome the trauma caused by illness, grief, and humiliation. Her small-format works exude frustration with the corrupt systems that push Roma and other disadvantaged people to the margins of society, exposing heartless practices with a defiant, even aggressive, tone. Going from being a cleaning lady to an internationally acclaimed artist, Omara used her voice to express the anger and pain of the voiceless, of the oppressed. Some of her works presented in the show illustrate the everyday racism one can find in schools, nurseries, and social services, criticizing these institutional care systems and underlining again, the differences in distributing protection. For example, a painting from her blue period, titled Little Mara in First Grade, 1952 (1998) depicts a subjective experience: one can see in the foreground two schoolgirls and a teacher next to them. While one of the two schoolgirls, with twisted hair and fair skin, watches amusedly, the other one, with dark skin, is being brutishly grabbed by her wild hair by a teacher who forces her head down to the opened book in front of her. Two girls silently watch from the back of the classroom. The inscription, written with thick lines in Hungarian, translates as: “But if she doesn’t tolerate it, she’ll end up in a reform school, like other gypsy kids.” While the painting suggests the resilience Roma children need to be capable of interacting with the majority population, it also reminds us that racism in Eastern European schools is sadly as current as a topic nowadays as it was 70 years ago.

The topic of racial segregation also constitutes the background of Phil Collins’ heartfelt video for Cate Le Bon’s touching single Home to You, which, in my opinion, served as a soundtrack for the entire exhibition. The video was filmed in Lunik IX, a suburb of Košice, Slovakia, which is home to one of the largest Roma communities in the country. Housing approximately three times more people than it was originally intended to, the ghetto-like neighbourhood has deplorable living and health conditions. A failed Communist-era relocation project, whose purpose was to force Roma to assimilate, the conditions in Lunik IX worsened even more in the 2000s when the local authorities decided to cram all sorts of marginalized people there, including homeless citizens, which created even more problems. However, the video doesn’t depict the grim or sensational images that the media usually shows. Instead, it presents members of the community and their everyday joys, approaching hardships with lightness and dignity. Throughout the video, a sense of solidarity among the community members prevails, whether it’s about helping each other, taking care of the children, or simply co-existing together. It was one of the many examples in the show that demonstrated that art has the power to expose different perspectives and to decisively sensitise us when introduced to painful topics. It also has practical implications – in this case, a part of the proceeds from Cate Le Bon’s album was redirected to an educational initiative aimed at connecting young people from Lunik IX with people from other parts of the city, providing them with schooling in filmmaking.

Solidarity and ways of being, living and working together, continued to be addressed in the next room, where one could see the installation of Czech artist Kateřina Šedá, No Light (2010-2023). Conducted over the course of more than 10 years, the project centers around industrialisation at the cost of leading a traditional way of life, as was the case for the inhabitants of Nošovice, a village in the Czech Republic, where a huge Hyundai automobile plant was built right in the center of the community, completely disrupting it. The industrial site created something akin to a black hole in the village, dividing it in two and causing many people to relocate or to not be on speaking terms with each other anymore. The title No Light comes from the response of the villagers when asked about the Hyundai plant, as they claimed to perceive no light at the end of the tunnel. Their hopelessness was what motivated Šedá to conduct the collaborative project, giving locals the opportunity to have some agency and to reconnect with each other. In the exhibition, triangular textiles were hung on wires, as if they had been left out to dry. The colourful pieces featured a variety of organic, floral and figurative motifs, all punctured by a hole or multiple holes right in the center of the decoration. The hole became a leitmotif for Šedá’s installation, being at the center of handsewn household items which would normally be part of a bride’s dowry. The hand-made textiles were created by women from Nošovice, encouraging a sense of belonging and shared creativity, in an attempt to combat the results that mass industrialisation has globally on local cultures and nature.

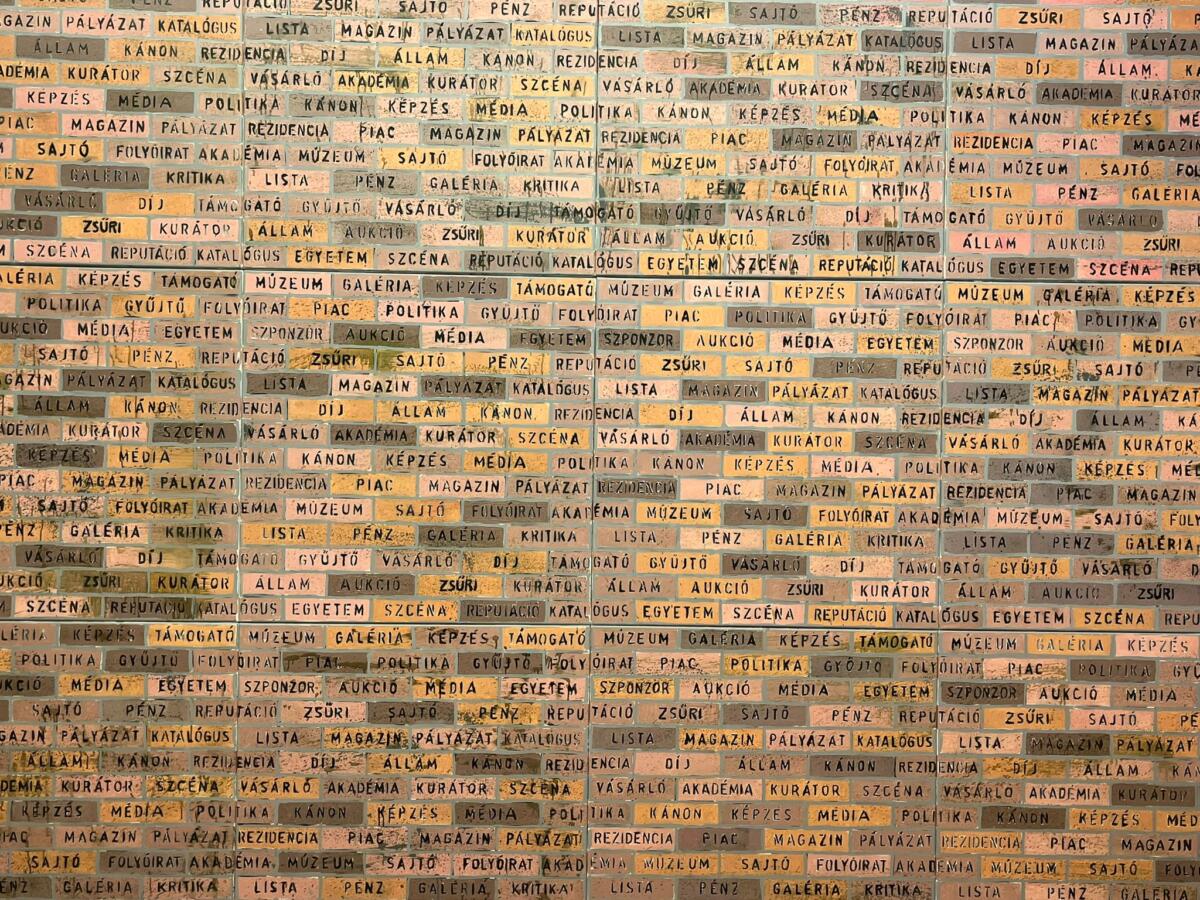

Something that does not get addressed often enough, especially in an Eastern European museum context, is the precarious structure of the art field itself – a highly competitive area with limited resources, often encouraging toxic, ego-fueled power dynamics among its members. Touching on this, Norbert Oláh created a site-specific installation resembling a brick wall where he mapped everyday anxieties of artists. He wrote on each brick different nouns in Hungarian, relating to factors that have a great influence on the modes of production and on the artistic field, such as “politics”, “museum”, “sponsor” or “critique.” Suggestively titled The Anxious Field of Art (2023), the work questions self-imposed limits and proposes their deconstruction. By visualizing the fears, one can understand that sometimes they are just words that shouldn’t hold such a big power over our psyches. A small-scale video of the artist himself wishing around 250 of his young artist colleagues good luck and good fortune accompanies the installation, a gesture of care and support that is not often encountered in this field.

Instead of a conclusion, I would like to mention Kata Tranker’s sculpture, Riders of Mother Nature (2021), made out of paper, hemp, wood and silk. The artwork depicts a humanoid creature that brings together ancient attributes of the feminine, recalling a mythological figure carrying two smaller female characters on her back. Everything in the scene is interconnected: the two riders hold each other, with the one in the front supporting herself on the back of Mother Nature. The sculpture is reminiscent of equestrian statues that we often encounter in public spaces. In contrast to these masculine symbols of power and force, Tranker’s work suggests a monument for the nurturing caregivers who carry the world on their backs. The two figures do not have a stiff, upright position suggesting overbearing confidence as we usually see in equestrian statues. They look rather like tired and worried ancestral mothers or goddesses. One of them is holding up a large purple flag, one of the least used colours for national flags. It could be the flag of a newly formed nation, based on values and ideas different to those that have more typically led us into so many wars and conflicts.

Imprint

| Artist | BAGLYAS Erika, Maria BARTUSZOVÁ, Oksana BRIUKHOVETSKA, Elina BROTHERUS, Seba CALFUQUEO, Alexandr CHEKMENEV, Phil COLLINS, Anna DAUČÍKOVÁ, EPERJESI Ágnes, ESTERHÁZY Marcell, FAJGERNÉ DUDÁS Andrea, FÁTYOL Viola, Andreas FOGARASI, Coco FUSCO, Anna HULAČOVÁ, Sanja IVEKOVIĆ, KIS Judit, LŐRINCZ Réka, Kateryna LYSOVENKO, MATERNAL FANTASIES, OLÁH Norbert, Oláh Mara OMARA, Kateřina ŠEDÁ, SZÁSZ Lilla, SZENES Zsuzsa, TARR Hajnalka, TRANKER Kata, VÉKONY Dorottya, Stephanie WINTER |

| Exhibition | HANDLE WITH CARE |

| Place / venue | Ludwig Múzeum |

| Dates | 15. September, 2023 – 14. January, 2024 |

| Curated by | Rita Dabi-Farkas and Viktoriá Popovics |

| Index | Alexandr CHEKMENEV Andreas Fogarasi Anna Daučíková Anna Hulačová BAGLYAS Erika Budapest Coco FUSCO Elina BROTHERUS EPERJESI Ágnes ESTERHÁZY Marcell FAJGERNÉ DUDÁS Andrea FÁTYOL Viola Hungary Kateřina Šedá Kateryna Lysovenko KIS Judit LŐRINCZ Réka Ludwig Múzeum Maria BARTUSZOVÁ MATERNAL FANTASIES Oksana Briukhovetska Oláh Mara OMARA OLÁH Norbert Phil Collins Rita Dabi-Farkas Sanja Iveković Seba CALFUQUEO Stephanie WINTER SZÁSZ Lilla SZENES Zsuzsa TARR Hajnalka Teodora Talhoș TRANKER Kata VÉKONY Dorottya Viktoriá Popovics |