Blok Magazine talked with the famous curator Nicolaus Schafhausen about his latest exhibition entitled “Tell me about yesterday tomorrow” that was opened in November 2019 in Munich. Schafhausen has curated a number of international festivals and exhibitions. Since 2012 he has been the Strategic Director of Fogo Island Arts, an initiative of the Canadian Shorefast Foundation to find alternative solutions for the revitalization of the area that is prone to emigration.

Now Schafhausen has a leadership position at the Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism in Munich that mission is to educate and remember the history of National Socialism. In addition to curating exhibitions, national pavilions and other curatorial projects, Schafhausen has led before institutions such as the Frankfurter Kunstverein, the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam and held the position of the Director of Kunsthalle Wien. In 2007 and 2009 he was the curator of the German Pavilion for the 52nd and 53rd Venice Biennale.

***

How do you find the role of art in creating our common memory?

Nicolaus Schafhausen:Firstly, I believe that in art, one should be able to do, think, try, attempt and dream of everything. Art must be a place where you can promote current discussions as to how we can re-organize our relationships with each other and with the places we engage and/or function with. And I also think neither art nor culture can be isolated from our history. We need to get on with developing something completely different, in terms of both the form and how the topic of the “culture of remembrance” is dealt with. I think, art can bring many nuances into play, start discourses and formulate questions. Our current global realities are more and more detached from the historical past and there a fewer time witnesses who could report directly, that is why we need to find new ways to keep memory alive and I think art could be a powerful mean to support this aim.

What’s your opinion about combining the mission of cultural institutions with public places of memory to create exhibitions of contemporary art? Does such intervention pull out to the daylight new important contexts?

I am convinced that we need more joint ventures that connect the fields of art and culture with historiography, science and politics. The exhibition “Tell me about yesterday tomorrow” and the associated projects and productions are an attempt to find a new way of cooperation, of creating new approaches towards history and to include other aesthetic moments in the curatorial process. Today, we find ourselves in a situation where resentment is once again stirred up, freedoms are threatened, and where culture, especially memory culture, has become a political battle field to polarize society. Therefore, I see a great chance in establishing a greater connection between art, science and other disciplines in order to advocate liberal values and democracy.

Do you think that we should feel responsible for creating something we could call “European memory” and educate the international public about our common heritage? Was this your aim, to bring new awareness to the public and expend our memories?

Memory culture and the reflection of the past plays an indispensable role for the future of liberal democracy. In a society characterized by mobility and networking, social and political issues are always globally interlinked. The international view was central to the exhibition “Tell me about yesterday tomorrow” from the very beginning. It highlights, among others, suppressed, marginalized and forgotten histories from around the world. However, they also speak for attempts of marginalized groups to claim recognition and in some cases for restitutions for oppressions, disposessions or displacements they have experienced in the past. I think it is important to give light to these unresolved stories which could also link to a transcultural memory – in Europe but even beyond.

Gregor Schneider, ‘Essen’, 2014, film still Courtesy the artist

How we can avoid Instrumentalization of art?

It’s not necessary to avoid Instrumentalization of art because aren’t we all instrumentalized by life itself? We all have to question ourselves and ask why are we operating in the field of art. I think it is not enough to just comment. Too often art is in the position of being on the defensive side. I think there is huge potential if we gave up affirming the status quo. So the questions I have been asking include, what are artists doing and why are they doing it? Too often we operate in a comfort zone; people make their living out of a system, artists are entrepreneurs and are just as much part of that global system. But we need to stop just taking advantge of the system without reflecting on what the implications are doing so. Art should emerge out of necessity! If art is to help us open up to the world, art has to be irritating and uncomfortable in order for us to face issues that we would otherwise not address. I would like to see artists and curators today to position themselves, think outside expectations of others, as well as to foster an awareness for achievements of our time being under threat. One has to confront culture with society. No provocation for the sake of provocation, but a well thought-out and passionately formulated partisanship for endangered culture. Historically, complaint always constituted the means to grasp social problems and thus to work towards change. Cultural production as such should not only constitute the representation of the existing.

Do you believe you can make an impact, avoid the repetition of the vicious circle of the history, bring a social change by curating such exhibitions? Do you have your personal motives in the role of being a curator?

If events in history are being treated as singular and isolated phenomena, it is difficult to relate them to the present day. In history, there is always a before and after, which prepares the way or favours certain tendencies. Learning from history is important in order to understand the present and form the future, to recognize similarities and examine where we have to intervene in the political and public sphere. I think we do not have institutional models at the moment that are able to represent current problems. I believe, today, maybe more than ever before, we need to negotiate social issues outside the established fields on an artistic, curatorial, and thinking level. Images and ideas of – past, present and future – realities correspond a lot with sharing, and to modifications which occurs upon retelling history. Story telling, the writing of history and the production of certain images is extremely important in a political discourse and I think it is a great chance if art contributes to a wider discourse – but therefore must also leave the “safe space” of art museums. We are pretty aware that not a single event or exhibition makes a big change but many efforts and joint projects with a broad range of collaborators. We see the Munich project definitely as a point of departure to foster new ways of thinking and working together.

What was your key in the selection of artists? How it happened that you had invited two Polish artists Paweł Kowalewski and Joanna Piotrowska to the exhibition?

For the selection of artists we considered a number of different dimensions. Some of the invited artists have worked on historical topics, sometimes with biographical references, for a long time and have been active in promoting unresolved histories. Moreover, we collected topics which are central to our work at the Munich Center for the History of National Socialism, along with issues of current debates, and which link historical experience and the present.

The German and the Polish history is closely connected and as we attempt to augment the historical exhibition at the Documentation Center with international perspectives, it was important to also include art from Poland. However, I would see both Joanna Piotrowska and Paweł Kowalewski as international artist. There works included in the exhibition also deal with topics of power structures and built environments that foster separation. Joanna’s photographs portray animal shelters of almost extinct species and remind on the relationsship between different living beings but also point towards modes of coexistence and domestic as well as artificial surroundings. The work of Paweł shows a warning sign he encountered in Johannesburg and which is a relict of the Apartheid regime.

We also present two historical paintings by Artur (Stefan) Nacht-Samborski who was born in 1898 as Artur Nacht. Under German occupation of Poland, the artist was deported to the Lwów Ghetto in 1941. He managed to flee to Krakow in 1942 and later to Warsaw where assumed a new name, Stefan Samborski, and survived the rest of the war with the help of this false identity. His story presents an unusual fate which may would also not be possible like this today, where surveillance and data collection is omnipresent.

What do you find inspiring and fresh in Polish contemporary art scene and what else can be done here in Poland on the field of audience development?

This question allows many answers and thoughts. I do think that there is a desire for repeating similar narratives in Polish contemporary art. Again, art needs to be a place where current discussions can be asked about how to reorganize relationships, how to occupy places, regardless of nationality. Overall, I would like Poland to focus less on its own nation and, in particular, less on the part of the victim’s own role, but more progressively dealing with the extent to which the complex and indeed problematic past plays a role in life in a globalized world today. That means: what does the past have to do with us today and vice versa. Of course, the art market also plays a significant and not to be underestimated role in the art scene – more imports from outside would certainly do well for Poland. From the state side, more international exchange projects for international artists, curators, critics and authors should be offered. But all of this is too brief: maybe we should plan a round table discussion with several protagonists from different backgrounds and interest groups.

Material prepared by: Monika Tramś, Adam Mazur.

***

Pawel Kowalewski ‘Forbidden Europeans only’, lightbox, 2010, Exhibition ‘Tell me about yesterday tomorrow’ in NSDOKU Munich

Paweł Kowalewski, EUROPEANS ONLY

The series of photos FORBIDDEN was prepared over several years during my travels. I took various photographs of different signs with orders or injunctions and I made reproductions on their basis. The cycle was firstly presented at the 2. Mediations Biennale in Poznań in 2010. The main sign for the Biennale was Europeans Only printed on a large format banner. Photography was taken at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg and shows a railway station in Pretoria from the apartheid times (1992). The series of photos FORBIDDEN was also part of my performance during the Venice Biennale in 2011. I visited tourist stalls and kiosks selling souvenirs. To the commercial offer I added my post cards with multicultural directives. The Europeans Only was also exhibited at the Viennacontemporary Austrian art fair in 2016 and in Propaganda Gallery as a main program of Warsaw Gallery Weekend in 2019. Now the piece is presented in Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism in Germany.

The text “Europeans only” is a symbol of the system which divide people based on their race and the colour of their skin. Opened in 2001 in Johannesburg, the Museum of Apartheid was created so as to document the 20th century history of Southern Africa in which apartheid played such a central role. Racial segregation in 2001 seemed to be something which had disappeared in the mists of the previous century.

If we look at the modern world through the camera lens, we will see that our need for safety and order locks us all up in a cage of bans and permits we have to obey. We will see a universal language that determines our behavior, a language which is commonly understood by Europeans or Africans. This is a language that speaks nonsense and exposes helplessness…

Don’t we all hide behind the system of bans in order to stay in our comfort zone?

Don’t we all perceive the system as the unquestionable law?

2010 – France deported a Romanian citizen of gypsy origin

2011 – Death squads murder foreigners in Germany

2012 – Dutch authorities encourage citizens to report foreigners

This is my personal 2020 notice from Pretoria station.

Paweł Kowalewski

Imprint

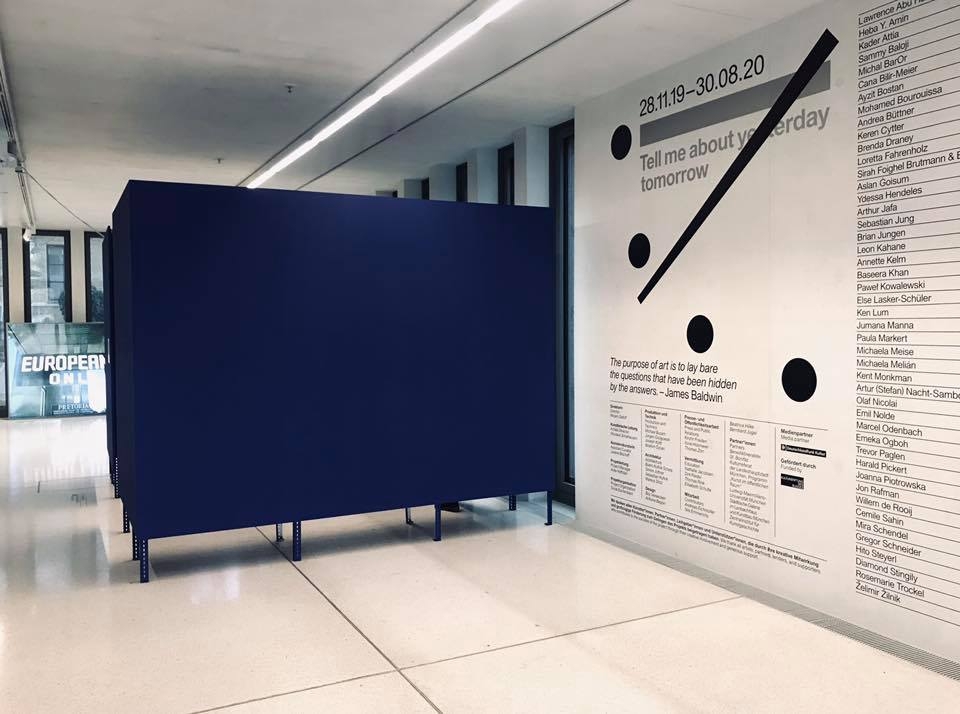

| Artist | Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Heba Y. Amin, Kader Attia, Sammy Baloji, Michal BarOr, Cana Bilir-Meier, Ayzit Bostan, Mohamed Bourouissa, Andrea Büttner, Keren Cytter, Brenda Draney, Loretta Fahrenholz, Sirah Foighel Brutmann & Eitan Efrat, Aslan Ġoisum, Ydessa Hendeles, Arthur Jafa, Sebastian Jung, Brian Jungen, Leon Kahane, Annette Kelm, Baseera Khan, Ken Lum, Paweł Kowalewski, Else Lasker-Schüler, Jumana Manna, Paula Markert, Michaela Meise, Michaela Melián, Kent Monkman, Artur (Stefan) Nacht-Samborski, Olaf Nicolai, Emil Nolde, Marcel Odenbach, Emeka Ogboh, Trevor Paglen, Harald Pickert, Joanna Piotrowska, Jon Rafman, Willem de Rooij, Cemile Sahin, Mira Schendel, Gregor Schneider, Hito Steyerl, Diamond Stingily, Rosemarie Trockel, Želimir Žilnik |

| Exhibition | Tell me about yesterday tomorrow |

| Place / venue | Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism |

| Dates | 28 November 2019 – 30 August 2020 |

| Curated by | Nicolaus Schafhausen |

| Website | www.ns-dokuzentrum-muenchen.de/en/special-exhibition/upcoming/tell-me-about/ |

| Index | Nicolaus Schafhausen NSDOKU Munich Paweł Kowalewski |