![[EN] Words and Deeds: Operation Białystok and insurrection](https://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/1-1200x800.jpg)

Some might wonder: why rummage in such a distant past? What can these old stories teach us, [these] anarchists of the twentieth century? We’re certainly not historians and precisely for this reason we think that the lives of comrades who came before us are of value if they transmit us strength, tenacity, coherence, living experience.

– Alfredo Cospito, foreword to Anarchici di Białystok 1903–1908, (Edizioni Bandiera Nera 2018)

At dawn on 12 June 2020, seven “dangerous anarchists” were arrested in Italy, France, and Spain, and the social centre Bencivenga Occupato in Rome was raided and accused as the headquarters of a purported anarchist “cell” to which the detainees allegedly belonged. Mounted by the elite ROS (Special Operational Group) unit of the Italian Carabinieri in coordination with French central police and the Spanish national police, the name given to this international operation was surprising: Operation Białystok. Why would an “anti-terrorism” campaign targeting anarchists in Mediterranean Europe be named after this modestly sized city at the northeast periphery of Poland? This question not only connects the actions of Białystok anarchists at the beginning of the 20th century to present acts of political dissent, but also can give a perspective on the evolution, repression, and representation of anarchism in our times of global ecological and political crises.

The simple answer to the question, “why Białystok?”, is that the police operation sought to tie the activists to a recent Italian translation of the Spanish-language publication Anarquistas de Białystok, 1903–1908. In 2009, Furia Apátrida and Edicions Anomia in Barcelona and Manresa published the book, anonymously collating and translating resources from Russian, English, and Yiddish into Castilian Spanish. The compilation of autobiographical testimonies, essays, political leaflets, and obituaries focuses on the personal stories of activists in Białystok, Krynki, and the region, serving, above all, as an indispensable resource for scholars and activists to understand revolutionary movements in the early the 20th century and the cultural and political history of the region. By looking back at Białystok, anarchists are attempting to reknot a transhistorical and transnational “black thread” that binds the anarchism of yesterday with the contemporary praxis of insurrection, re-introducing into the “canon” the radical tactics and life stories of this brief but intense moment.

Despite its multicultural history, for most in Poland, Białystok is more known for its role as a recent bastion for far right, homophobic, and nationalist radicalism. Even the influential anarchist and anti-fascist squat Decentrum in Białystok (which operated in an abandoned factory from 2000–2005) were largely unaware of the full scale of the anarchist history of their own city until this knowledge was shared by international comrades.[1] Yet Anarquistas de Białystok, 1903–1908 has become very popular for activists in Spain and across Latin America, and it was reprinted in 2011 and widely distributed as pdfs on online forums. It has also appeared at anarchist book fairs, and in squats and infoshops in such places as Chile, Mexico, Uruguay, and Colombia, and graffiti referring to Białystok has appeared amidst recent uprisings in Latin America and the Mediterranean. Published without copyright, the book exploited online and offline research networks vital to the continuation of anarchism today, and these spaces are now the very sites where this publication can be found, inspiring further research.[2]

In 2013, two Italian anarchists, Alfredo Cospito and Nicola Gai, began translating the book into Italian from high surveillance prison units while awaiting trial for the 2012 “kneecapping” of Roberto Adinolfi, the CEO of Ansaldo Nucleare, the nuclear division of the state-controlled defence and aerospace group Finmeccanica. The translation was later revised and extended in collaboration with their comrades inside and outside prison walls, including members of the anarchist library Sabot. The Italian edition was finally published in 2018 by Edizioni Bandiera Nera as Anarchici di Białystok 1903–1908, serving as “a small demonstration of the fact that even the down times imposed by imprisonment and censorship can’t stop ideas and will.” With a bloody dagger on its cover, this publication is now being used as evidence to persecute the ideology, motivations, and historical heritage of recent anarchist “terrorist” operations.

Operation Białystok began in December 2019 when a rudimentary bomb exploded outside a Carabinieri police barracks in Rome, claimed by the ” Informal Anarchy Federation – International Revolutionary Front (FAI-IRF ), Cell Santiago Maldonado”. This led to a monitoring of the Bencivenga Occupato social centre, and the arrest of five people there as well as two others that were arrested and extradited on European arrest warrants. They are charged with “criminal association for the purposes of terrorism and subversion against the state”, “instigation to commit crimes”, and various terrorist or subversive offenses. Only one detainee was charged with the bomb at the police station, while another was charged with a series of attacks on Enjoy cars, a carsharing service linked to ENI, the Italian multinational oil and gas company. The other charges against them concerned activities related to the Bencivenga Occupato. Such activities include issuing communiques, graffiti and posters around Rome, meetings and reading groups, practices of mutual aid, correspondence and demonstrations outside and inside prisons, the blocking of the eviction of a house, and conducting a hip hop festival and other events and initiatives in solidarity with defendants of the “Panico” trial, where nine people were arrested when a bomb was set off in 2017 outside a neo-fascist Casa Pound bookstore in Rome (one of the Białystok arrestees is also a defendant in this trial). Prosecutors cite the arrest of a Basque anarchist at the social centre, the visitation of a Chilean anarchist indigenous rights activist, and frequent trips by members to Greece and Berlin as proof of an international conspiracy. Operated for over 19 years a few steps from the provincial Ministry of Finance headquarters, Bencivenga Occupato was a squatted autonomist social centre with various initiatives and social purposes not unlike over one hundred such spaces across Italy, and thousands across the world, engaging in mutual aid, conducting educational and community workshops, sharing and writing revolutionary literature, and organizing concerts, meetings, demonstrations, and solidarity projects.

It is unclear if any of those arrested in Operation Białystok had anything to do with the Białystok publication in either language. The use of this reference by the police was likely meant to draw an ideological and organizational connection to Alfredo Cospito, who wrote the foreword to the Italian publication and participated in the translation. Investigators seek to frame the imprisoned Cospito as a lead “ideologue” of the FAI-IRF, a decentralized instrument for direct insurrectionist action that emerged in 1998 from various anarchist movements in Italy and Greece and has spread since 2003 internationally through a wide range of claimed and unclaimed bombings and attacks on capital and the state. Cospito is certainly outspoken as a writer of revolutionary texts that critically address our time of ecological and political crisis and reflect on FAI-IRF actions and other associated movements such as the Conspiracy of Cells of Fire (CCF) in Greece. Yet to refer to him as a leader of any sort is to fundamentally misunderstand the clandestine, horizontal, autonomous, and informal structure through which the FAI-IRF operates. The FAI-IRF is not an organization, but a tendency of attack. Unlike social movement organizations and political campaigns, one does not “belong to” the FAI-IRF, but rather “acts through” it. In describing one’s enrolment with the FAI-IRF, Cospito states:

One becomes part of FAI-IRF only at the very moment he/she acts and strikes claiming as FAI, then everyone returns to their own projects, their own individual perspective, within a black international that includes a variety of practices, all aggressive and violent.

Over the last decade over one hundred attacks have been claimed by cells of the FAI-IRF spreading from Greece, to Italy, Turkey, Spain, The Netherlands, Peru, the USA, Bolivia, Mexico, France, Chile, Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, Germany, Czechia, England, and beyond. Targets have included prison and police officers, prosecutors, diplomats, power plants, train infrastructure, election offices, hotels, a sawmill, a cell phone antenna, a meat company, multinational corporate franchises, and numerous ATMs, gas stations, and police and security cars. By identifying themselves with an organizational acronym, combatants tag their act as ideologically insurrectionary and associate their attack with others, producing a decentralized ongoing campaign of sorts by using a collective moniker[3]. As the social justice and peace studies scholar Michael Loadenthal explains, FAI-IRF actions are a “momentary assemblage of like-minded individuals united for a particular attack by voluntary association and through shared affinity.” The individual cells temporarily form, carry out attacks, and alternate between anonymous, unclaimed, acts and announcing these strikes widely through communiques and publications that claim these actions as part of a bigger campaign, cite local circumstances, and express solidarity with other attacks, movements, and those in prison. One cannot underestimate the role of the internet in this movement’s expansion, as well as how this technology has expanded the ability to monitor closely the activities of individuals and groups deemed potentially subversive or dangerous to society. By circulating texts on a broad range of anarchist and autonomist websites and forums, the tactic has been able to spread globally without any leadership, coordination, structure, or even knowledge between different groups and individuals, maintaining a “informal”, chaotic, and horizontal praxis in contrast to more organized social justice movements. As imprisoned members of the CCF state: “the Informal Anarchist Federation travels over borders and cities, carrying with it the momentum of a lasting anarchist insurrection.”

Juan Pablo Macias, WORD+MOIST PRESS VOLUME 5, 2021; editorial project, Polish language edition of Anarquistas de Bialystok, 1903-1908 translated by Jan Wąsiński; with support from Instituto Cervantes Warsaw

Ewa Axelrad, Shtamah #2, 2017; ash wood flag poles, steel pole holders, dimensions variable, photo: Tytus Szabelski

It is indeed this anti-organizational and transnational praxis that has made insurrectionary anarchism in the 21st century both volatile and illegible to authorities. To combat insurrectionary actions in Italy, prosecutors have tested a wide range of legal manoeuvres around “criminal association” used for the mafia, international syndicates, fundamentalist terrorism networks, and to counter violent anarchist rebellions in Italy in the 70s and 80s. At times, they have been successful at tying specific individuals to certain attacks, but the focus over the last years has been on trying to frame the FAI-IRF as a structured group, and to allege that the rhetoric of different texts and activities are forms of incitement and acts of terror in and of themselves. Operation Białystok is one of a long line of recent operations in Italy with ominous names such as Scripta Manent (latin for “written words remain”). Building upon each other, these trials have sought to draw historical parallels and concrete connections between theory and practice, words and deeds.

At the beginning of one of the trials related to Operation Białystok, the head prosecutor Luigi Imperatore drew a historical line of insurrectionary tendencies from 19th century political assassinations and the “Black Banner” in Białystok, to Alfredo Bonanno’s 1977 book Armed Joy and The Invisible Committee’s 2007 The Coming Insurrection and recent insurrectionist attacks in Europe, South America, and Asia. Acting like political scientists and philosophers, the military police investigators have systematically analysed a wide range of texts and communiques to chart a lineage and “ideological contiguity” [4], rendering decipherable a chaotic movement by tracing influences, word-use, and platforms circulating this knowledge. The analysts suggest that the “dictates” that Cospito has published from prison are concretely provoking further insurrectionist actions, citing his essay Autism of the Insurgents, his interview Which International?, and the release of Anarchici di Białystok 1903–1908 as launching a new call to arms to the entire anarchist world. This has led to the targeting of online platforms, blogs, journals, and long-established anarchist newspapers who have published Cospito’s texts, FAI-IRF communiques, and expressions of solidarity with imprisoned anarchists.

Tellingly, they have also tried to shut down the Croce Nera Anarchica, the journal of the Italian chapter of the Anarchist Black Cross, an international organization supporting anarchists and other political prisoners whose roots can be found in the Anarchist Red Cross established in Białystok, Kiev, and Odessa amidst the 1905 revolution[5], and has grown largely unchanged in its political scope and tactics since. Solidarity is a key principle in anarchist thought, containing the fundamental notion of a bond between the individual and the collective, an acknowledgement of shared struggle, and an attack on the carceral state. While reformist and humanitarian movements use solidarity as a symbolic act of charity, insurrectionists and prison abolitionists emphasize a “revolutionary” or “conflictual solidarity” that not only involves writing to prisoners, raising funds for legal expenses, and publicizing individuals’ struggle, but concretely focuses on attacking the specific institutions, agents, and structures of the prison apparatus. In this sense, revolutionary solidarity is not a matter of defence, but of attack. Daniela Carmignani has described revolutionary solidarity as “A project which is a point of reference and stimulus for the imprisoned comrades, who in turn are a point of reference for it. Revolutionary solidarity is the secret that destroys all walls, expressing love and rage at the same time as one’s own insurrection in the struggle against Capital and the State.” FAI-IRF campaigns often claim their attacks in the name of their fallen or incarcerated sisters and brothers.[6] By recognizing that the rebellion of others expands one’s own freedom, mutuality and solidarity are embraced as forms of complicity and catalysts for action. In the revolutionary anarchist struggle, there is no moral difference between innocence and guilt, and no identification with concepts of “justice” within an abusive state.

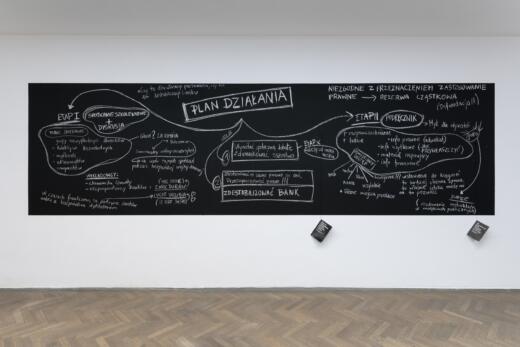

Núria Güell, Displaced Legal Application #1 : Fractional Reserve, 2010-2011; master plan and publication of manual, photo: Tytus Szabelski

By participating in assemblies and initiatives, writing in publications and blogs, or simply for having given solidarity and corresponding with imprisoned colleagues (including Cospito), Italian prosecutors have tried to frame common anarchist activities as forms of terrorist coordination. Key to the prosecutor’s thesis is to differentiate “good” anarchists and “bad” ones, drawing from internal debates and divides regarding strategies and organization within the social justice community itself. Their premise is that publishing activities, websites, solidarity groups, concerts and fundraisers, Food Not Bombs, and anarchist public spaces such as squats and social centres function as an “open tier” that provide cover and support for a “clandestine tier” engaged in robberies, bombings, and assassinations. It goes without saying that such a hierarchical structure would contradict the most fundamental anarchist principles. Many social movements today, anarchist or otherwise, emphasize a “diversity of tactics”, combining forceful direct actions with acts of mutual aid, movement building, and solidarity. For those using the FAI-IRF and other insurrectionary tactics, an “attack” is not simply a physical explosion or assault, but also includes a wide and multiform field of actions. As is frequently repeated: “the force of an insurrection is social, not military.” The translation of a book, the publication of an article or communique, an action in support of a fallen or imprisoned comrade, or the establishment of a squat or library, can be as dangerous and destructive to the system as a presence in street rallies or armed assaults on the symbols and agents of power. Proponents of insurrectionary practices are not willing to wait for the revolution or for the state to wither away:

“Attack is the refusal of mediation, pacification, sacrifice, accommodation, and compromise in struggle. It is through acting and learning to act, not propaganda, that we will open the path to insurrection, although analysis and discussion have a role in clarifying how to act. Waiting only teaches waiting; in acting one learns to act.”

This sense of urgency and immediacy regarding direct action is in profound contrast to most social movements today that often take a “wait and see” approach or only react to struggles rather than proactively working to change social relations and stop environmental catastrophe. Insurrectionist practices remind us that a revolution is not a progressive shift, but a rupture, a violent break with the status quo.

The FAI-IRF has not for the moment killed any person and they have not committed indiscriminate attacks against anonymous individuals. Their violence is more restrained than that of their Białystok ancestors and the infamous Red Brigades, RAF, Weathermen, and others of the 60s and 70s. The goal of such attacks is not to “out flank” the militarized state by meeting them head on, but to destabilize the system itself through spontaneous, disruptive, and unpredictable resistance.

The primary criticism today of such acts of “propaganda of the deed” is that the tactic reaffirms the stereotypical spectacle of the anarchist as a violent, bomb-throwing terrorist, distracting from the movement, and provoking further state repression that often targets the most marginalized.[7] Yet such condemnations often misunderstand legacies of civil disobedience through a reductive view of the concept of nonviolence. In the Anti-globalization movement at the turn of the 21st century, many on the left condemned black bloc formations and property destruction in Seattle, Prague, Genoa, and Quebec City as undermining the aims of the protests and damaging credibility through negative (corporate) media attention. Such critiques were led by NGOs and reformist unions who preferred permitted demonstrations and orderly “peaceful protests” and denounced anarchists in general for engaging in direct actions such as breaking the windows of multinational corporations. While one could argue that such tactics can be counter-productive, this overarching condemnation essentially reaffirmed the core capitalist value system that private property is more valuable than life itself, and erroneously suggests that police repression on protesters is justified.

The fact that many social movement organizations are so quick to demonize aggressive dissent has pushed anarchists away from traditional forms of organization and to take more clandestine and informal approaches. This debate between reformist, political methods of resistance vs. insurrectionary ones has changed very little since the time of the Black Banner. Indeed, much of the radical anarchists of Białystok were drawn to such tactics after growing weary of the ineffectiveness of traditional worker movements with their top-down forms of organization, self-policing of behaviour, and willingness to compromise and negotiate with oppressive forces. Echoing the stance of the Białystok anarchists a century before, The Invisible Committee state in The Coming Insurrection: “The first obstacle every social movement faces, long before the police proper, are the unions…”. Wanting neither leaders nor followers, informal anarchism is a countermeasure to the division of roles and the centralized model of organization often found in social and worker movements, including anarchist ones. “Organizations,” as The Invisible Committee note, “are obstacles to organizing ourselves”. Informal insurrectionist confrontation such as Black Bloc assemblies (which emerged in the 1970s in defence of squats in West Germany) and individual acts of subversion and sabotage enacted by affinity groups have become common in popular revolts across the world. While most movements stress visibility, these actions emphasize a cultivation of invisibility, opacity, anonymity, spontaneity, and what The Invisible Committee refer to as “resonance”, where diverse acts dispersed in time and space reverberate to shake the foundations of society.

Anarchism’s essential transnational and decentralized approach has always perplexed and perturbed authorities. Białystok’s anarchist movement was distinct from other movements in the region in that it built connections and collaborations across ethnic and religious lines, and between and outside different trades and classes. But it also was a vital node of a global network of anarchists that spread resources and literature from Paris, London, Geneva, Riga, and Warsaw, to disparate groups across the Russian Empire and beyond, including to the Americas. In fact, it was precisely this movement of anarchists and insurrectionist ideas that inspired some of the first immigration and extradition laws in the modern world and led to the establishment of national security agencies, universal passport and fingerprint systems, and international police and surveillance collaborations.[8] Given that anarchism as a whole has a declared goal of wanting to destroy the present institutional and economic order, it is no surprise that Capital and the State would want to stop this internationalist movement. This repression is intended to cause militants to back away from engaging with the public, losing connection with a broader social base and historical predecessors, and deepening the false dichotomy between passive “community organizing” and clandestine direct action.

In the last years, the tactics of formal organizations and direct democracy—consensus, popular assemblies, parades, open letters, petitions, voting drives, and so forth—have revealed their weakness as mechanisms for concerted resistance. Performative allyship and facile “peaceful” demonstrations rarely result in real social change. At the same time, we’ve observed disruptive uprisings topple regimes that decades of patient organizing had failed to dislodge. We’ve seen grievance-fuelled protests and anti-police uprisings demand that the lives and livelihoods of Black, Brown, and Indigenous bodies, and the unhoused, the enslaved workers, the LGBTQI community, the imprisoned, and others marginalized in our societies not only matter, but are volatile political forces that no longer are willing to wait or compromise. Our world today is literally and figuratively in flames. The struggles in which insurrectionist anarchists are engaged in are fundamentally existential. How bad does the climate need to get for us to act? How much violence needs to be committed in our communities for us to rise up? Why have we been taught to wait and accept this abuse of our labor, our bodies, and our Earth? In our state of constant and increasing crisis, we no longer can be obliged to political “realisms”, we must forget every social “fact”. Inspired from the experiences of the past, and rescuing these histories from erasure, we form resonances across time and space and incite the emergence of the seemingly impossible.

The text originally published in the zin “Na początku był czyn! / In the Beginning Was the Deed!”, Galeria Arsenał w Białymstoku, Białystok 2021

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1] Curiously, many of Decentrum’s campaigns and actions coincidentally occupied the same public spaces as their historical forebearers. Not only did they occupy a 19th century factory that likely was a site of anarcho-communist strikes, but they also enacted Food Not Bombs actions on Suraska street where an autonomous anarchist “birzha” had been formed, engaged in Antifa street fights with Neo-Nazis on Lipowa street, and initiated anti-border camp protests in Krynki, where the anarchist movement once grew to such a scale that a “Krynki Republic” was momentarily established. Like their forebearers, Decentrum functioned as an essential node connecting anarchists in the East and West of Europe, and lives on in a variety of ways.

[2] For instance, in 2016, a French publisher Mutines Seditions released Vive la révolution, à bas la démocratie ! Anarchistes de Russie dans l’insurrection de 1905. Récits, parcours et documents d’intransigeants, featuring further materials that were only available in French anarchist collections, a contemporaneous reflection on their tactics and histories, and connects actions in Podlasie to the wider insurgent movement of the time in Poland, Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus.

[3] There is also a bit of irony to their use, as FAI is also an appropriation of the acronym of the Italian Anarchist Federation that has lasted since 1945, who have been criticized for centralizing, controlling, and watering-down the anarchist movement in Italy through synthesis and reformism.

[4] For example, investigators have compared the wording in the communique issued by the Cell Santiago Maldonado regarding the bombing of the police barracks in Rome, to Cospito’s text “Dire e Sedire [Say and commit Sedition]”.

[5] According to Harry Weinstein, who is considered the father of the Anarchist Red Cross, he and a friend, B. Yelin, began the ARC in Białystok after being released sometime in August of 1906. The name of the group was changed to the Anarchist Black Cross by Olga Taratuta in Ukraine to accentuate their distinction from the “humanitarian” Red Cross organization amidst the Nestor Makhno’s movement against Bolshevik repression of anarchists. Unlike Amnesty International and other liberal groups, the ABC openly aids those who have committed illegal or violent actions with revolutionary aims.

[6] The attack on the police station in Rome was claimed by the cell “Santiago Maldonado”, a reference to an Argentinian activist who was allegedly drowned by police after a blockade for indigenous Mapuche land rights. The FAI/IRF cell that claimed responsibility for the Adinolfi shooting called themselves the “Olga Nucleus”, in support of the imprisoned Conspiracy of Cells of Fire member Olga Ikonomidou, and another series of attacks were claimed by the “Mikhail Zhlobitsky Nucleus”, after the suicide bomber who attacked a local Russian Secret Service office in retaliation for tortured and imprisoned anarchists there.

[7] This scapegoating can be seen in the Białystok Pogrom of 1906, where anarchist activities were used as a justification for the killing of 80 Jewish people, and injuring of more than 80 others.

[8] The perceived transnational threat of a ‘Black International’ conspiracy, was triggered by the global spread of attacks by anarchists who blew up public sites and targeted more heads of state between 1890 and 1910 than at any time before or since. Blaming immigrants for the proliferation of anarchism, the USA enacted The Immigration Act of 1903, also called the Anarchist Exclusion Act, which established four inadmissible classes: anarchists, people with epilepsy, beggars, and importers of prostitutes, and was later expanded to allow the deportation of anarchists back to their home countries. In 1898, representatives of the European powers met in Rome for the ‘International Conference for the Defence of Society against the Anarchists’, trading photographs and documents and in 1904, ten countries adopted “The Secret Protocol for the International War on Anarchism”, also known as the St. Petersburg Protocol, that arranged national policies for the rendition of anarchists to their origin countries and the exchange of information on anarchists. Today, the rise of FAI-IRF actions, Black Blocs, and other forms of sabotage and attack across the world has renewed this international anti-anarchist campaign.

Imprint

| Artist | Ewa Axelrad, Bernadette Corporation, Antoni Boratyński, Michał Bylina, Claire Fontaine, Dora Garcia, Girls to the Front, Núria Güell, Zuzanna Hertzberg, Anna Jermolaewa, Edka Jarząb, Sasha Kurmaz, Juan Pablo Macías, Asier Mendizábal, Tadeusz Milewski, Marina Naprushkina, Aleka Polis, Karol Radziszewski, Vlada Ralko, Daniel Rycharski, Wilhelm Sasnal, Siksa, Mikołaj Sobczak, Łukasz Surowiec, Iza Tarasewicz, Liliana Zeic (Piskorska) |

| Exhibition | In the beginning was the deed! |

| Place / venue | Arsenal gallery in Białystok, Poland |

| Dates | 8 August – 23 September 2021 |

| Curated by | Post Brothers, Katarzyna Różniak |

| Exhibition design | galeria-arsenal.pl/ |

| Index | Aleka Polis Anna Jermolaewa Antoni Boratyński Asier Mendizábal Bernadette Corporation Claire Fontaine Daniel Rycharski Dora Garcia Edka Jarząb Ewa Axelrad Girls to the Front Iza Tarasewicz Juan Pablo Macías Karol Radziszewski Liliana Zeic Łukasz Surowiec Marina Naprushkina Michał Bylina Mikołaj Sobczak Núria Güell Sasha Kurmaz SIKSA Tadeusz Milewski Vlada Ralko Wilhelm Sasnal Zuzanna Hertzberg |