At a meeting promoting a book of reviews of his own works from the 1990s, Zbigniew Libera said the last artist whose art was understood for the broad masses of Polish intelligentsia was Jan Lebenstein. Indeed, the artist worked within the commonly recognised canon of high culture. It was easy to read in his works literary, mythological and biblical themes, which émigré friends of the artist connected with the Parisian Kultura magazine community wrote about in the context of his works with knowledge and sympathy. “He was friends with Czapski, Herbert, Herling, Hertz, Jeleński, Miłosz, Father Sadzik, Wat.”[1] This was a community that was incredibly influential in shaping the intelligentsia aesthetic canon of the late Polish People’s Republic and the Second Polish Republic. Friendships and affiliations have great significance in the perception of one’s achievements. And why shouldn’t they? Culture happens in a multiplicity of perspectives and in a process of negotiation of values that are important to its participants today.

Lebenstein spoke from abroad, a place that was difficult to access – and thus, in the times of the Polish People’s Republic, particularly desired – in a language both familiar and innovative. He was a little bit “familiar”, but also a bit alien. It is worth nothing here that the Grand Prix at the Young Artists Biennale in Paris in 1959, which is mentioned in even the shortest notes about Lebenstein and which led to his moving to the West, resulted both from his talent and from the political situation in Paris. An award for an artist from the Eastern Bloc was desired, since the Paris Biennale was to be a counterbalance for the Venice Biennale, disgraced by its collaboration with Mussolini, and was established by a community of left-leaning Gaullists, led by the newly appointed Minister of Culture, André Malraux.[2] Lebenstein received the City of Paris Award in the form of a six-month grant and remained in Paris, as he likely harboured a greater dislike of the communists in Poland than those in Paris.

The artist had male friends (let us recall, “He was friends with Czapski, Herbert, Herling, Zygmunt Hertz, Jeleński, Miłosz, Father Sadzik, Wat”), but he also talked to women. Painter Leonor Fini, partner of Konstanty Jeleński, enjoyed a friendship with Lebenstein, who dedicated an essay to her after her death. Women critics, art historians, publicists and journalists wrote about Lebenstein, including Małgorzata Baranowska, Krystyna Czerni, Elżbieta Dryll-Glińska, Róża Fabjanowska, Renata Gorczyńska, Dorota Jarecka, Katarzyna Janowska, Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak, Bożena Kowalska, Wiesława Lipińska, Barbara Majewska, Monika Małkowska, Krystyna Mazurkówna, Mary McCarthy, Elżbieta Sawicka, Olga Scherer Elżbieta Sitek, Joanna Skoczylas, Joanna Polakówna, Zofia Romanowiczowa, Barbara Toruńczyk, Wiesława Wierzchowska, Joanna Żamojdo, Alicja Żendora and others. Many wise women. We would like their names to be remembered. Of course, the spectrum of subjects taken up by the critics was broad, as they had various perspectives on representations of gender, but a common theme can be seen – the idea that the women’s figures are somehow ugly and vulgar. Nevertheless, most of the women agreed that despite this, the figures kept their identity. There was also a lot of oscillation around iconographic themes designated for women, who could be either saints – preferably virgins – or reformed fallen women, or nudes with a glow of saintliness in one eye and marketable sex in the other. At least that is how they were read.

When it comes to naked bodies, it is also worth mentioning Lebenstein’s experience of war. It is hardly doubtful that the disintegration of social bonds, the universality of death and the sight of decay had an influence on his creativity and the subsequent sense of alienation described by critics. In times of peace, knowledge of mass death – unpredictable and depriving individuals of their sense of agency – can be like glasses permanently nailed to the head. Lebenstein was from the East. He was born in Brest-Litovsk in 1930. He entered the time of war with some knowledge of the world and saw this world being violently overthrown and destroyed. He experienced the disintegration. Can a person get rid of such a lens from their eyes?

When choosing the works for the exhibition, provided by collectors of Jan Lebenstein, and analysing the texts that for years have defined the artist’s legacy, we examined the subject from the outside, so to speak. Many texts cite the same anecdotes about the artist, similar stories are told at exhibition openings and in films. What was missing, however, was a new perspective on the art in which women (usually undressed) play such an important role. Following in the footsteps of classic texts of the feminist methodology of art history, such as those by Linda Nochlin, we cannot ignore the intertwining of history and personal narratives that describe Lebenstein. Paris of the 1960s and 1970s was not just the Kultura editorial office, works of art at the Louvre, or inspiring items of value found by the artist at the Museum of Natural History, which he liked to visit so much. Paris in the 1960s and 1970s also meant a series of social changes and second-wave feminism. People fighting for human rights at the time not only strove for changes in legislation and education, but also pointed out that discrimination was deeply rooted in the social and class structure. They critically examined what had previously been considered “natural” – the division into two spheres of life: public and private. The public “traditionally” belonged to men, while the “natural” veil of privacy was to separate the sphere of women from the remaining social life spaces. “The personal is political” was one of the most important slogans of the human rights movement of the time.

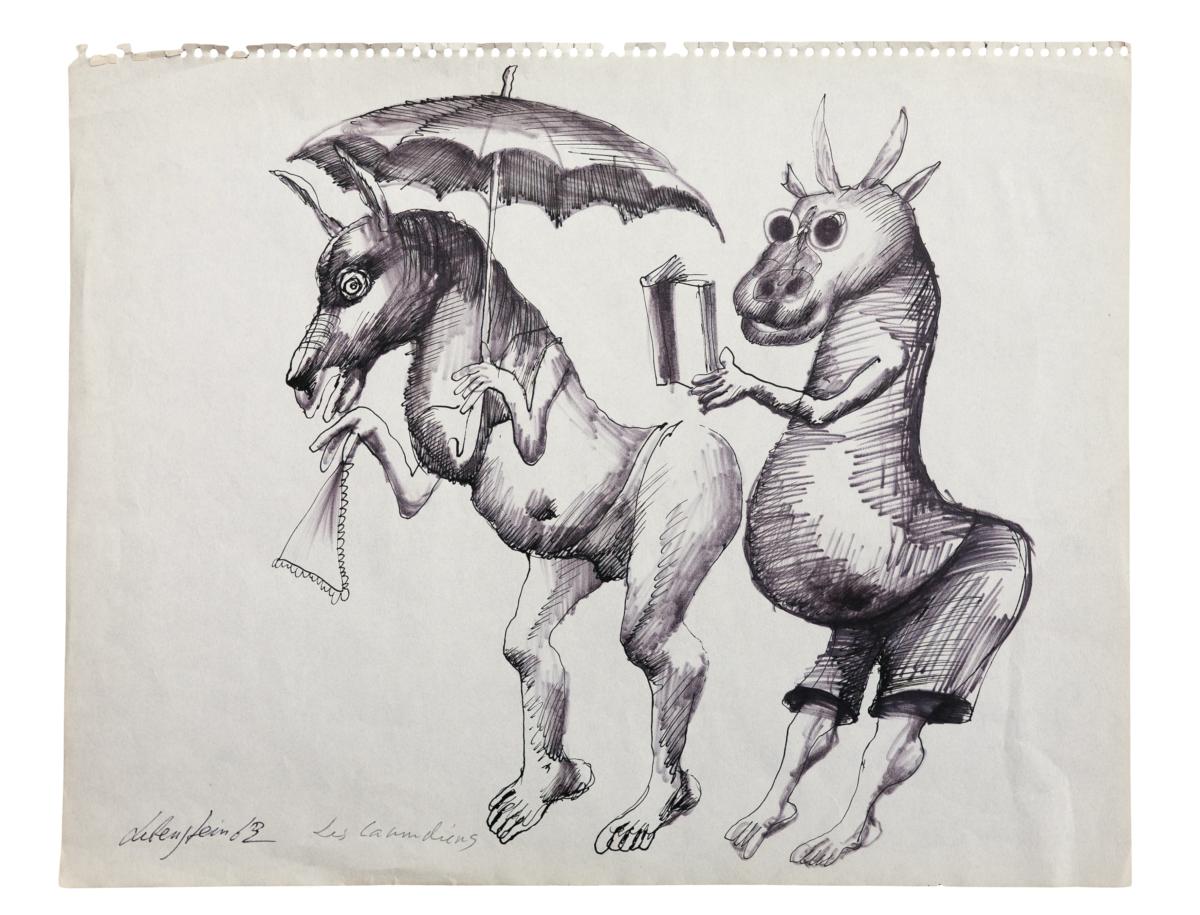

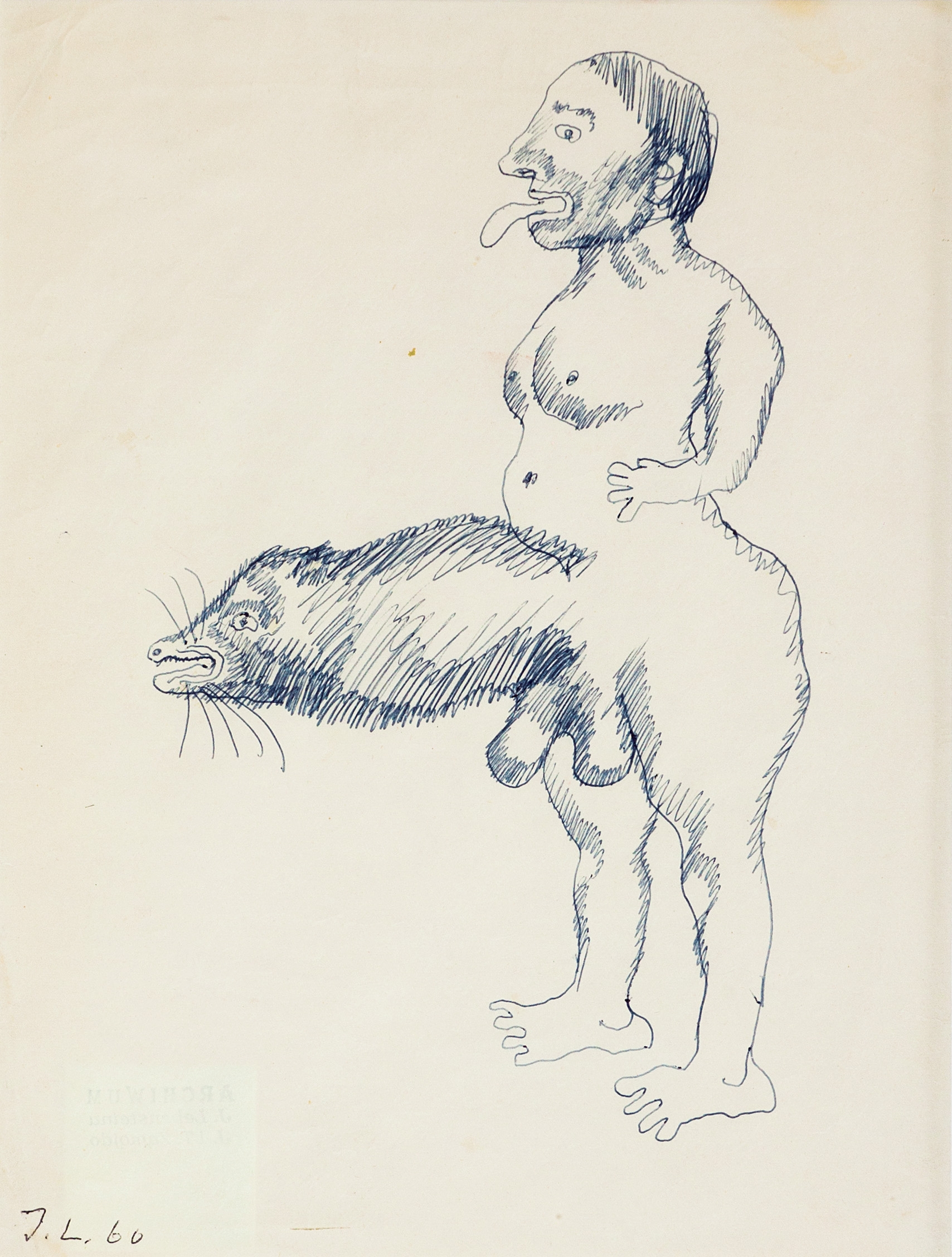

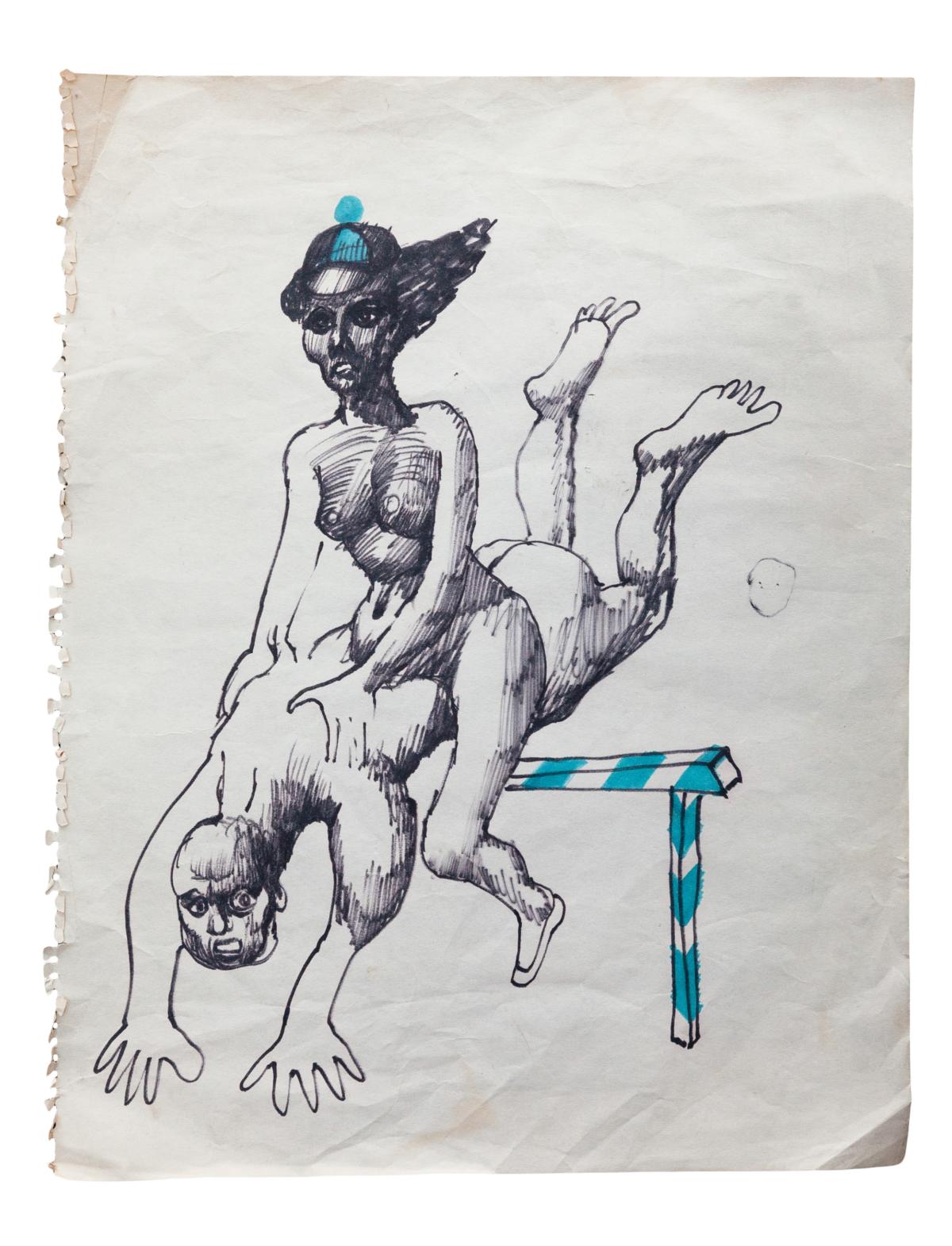

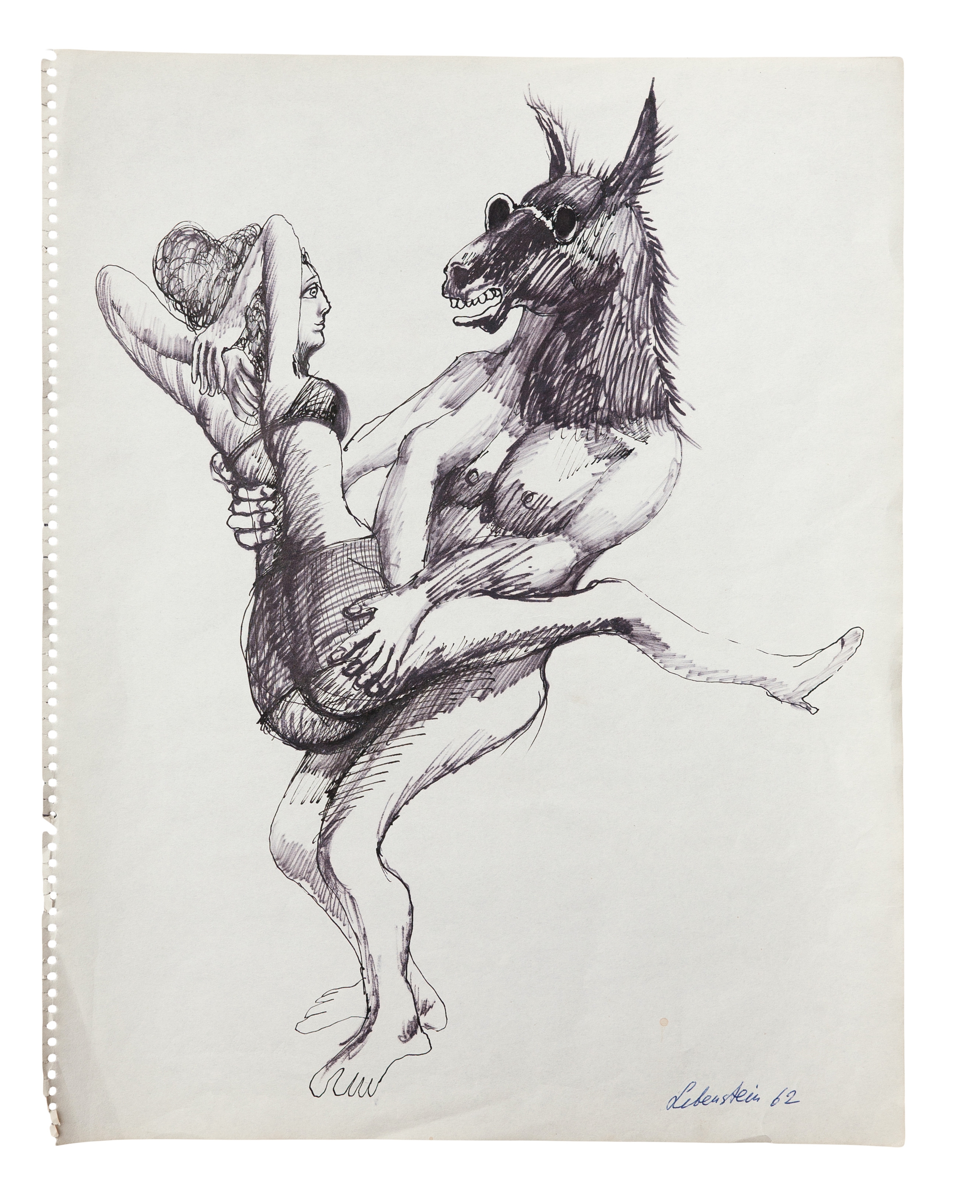

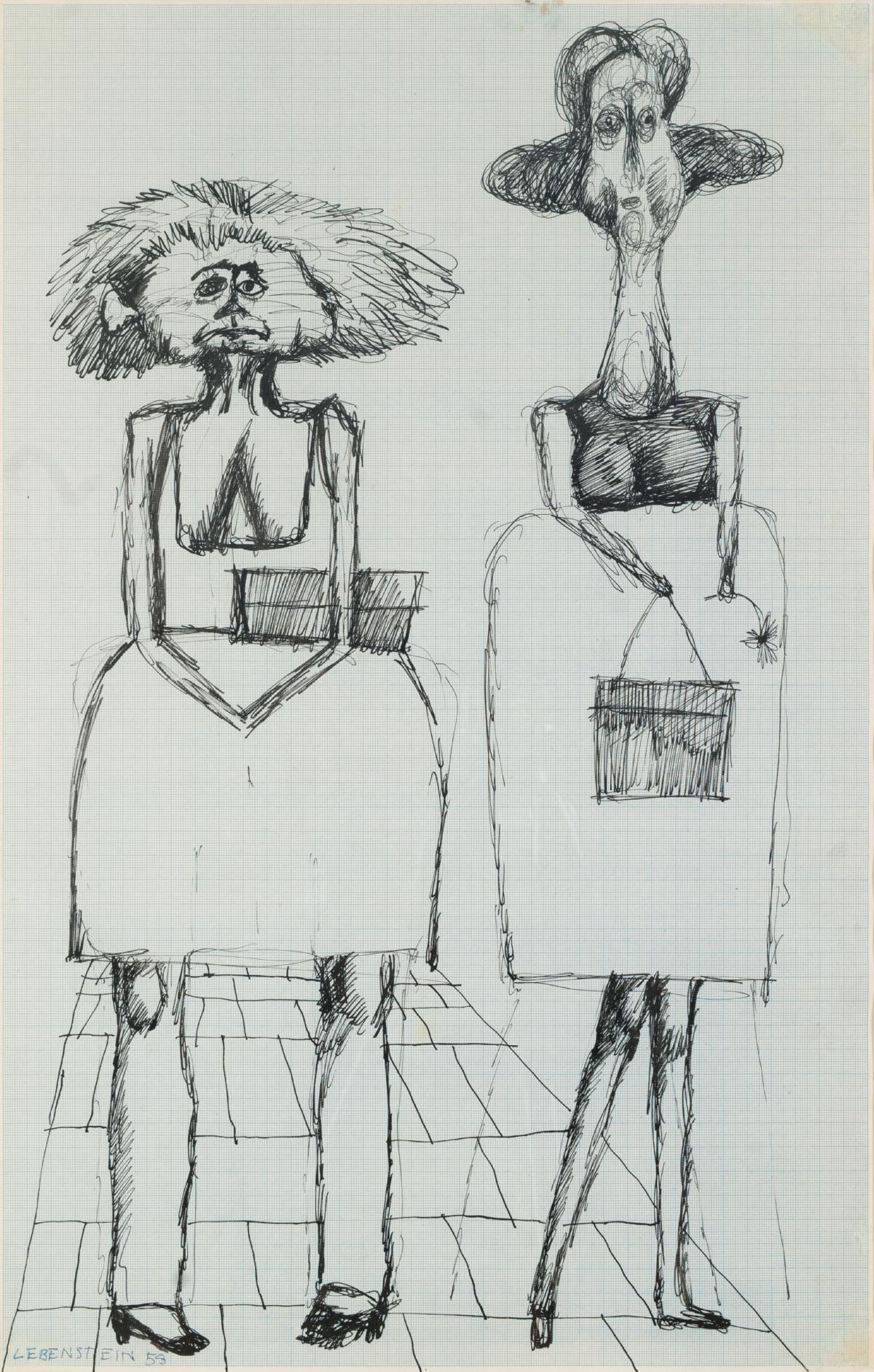

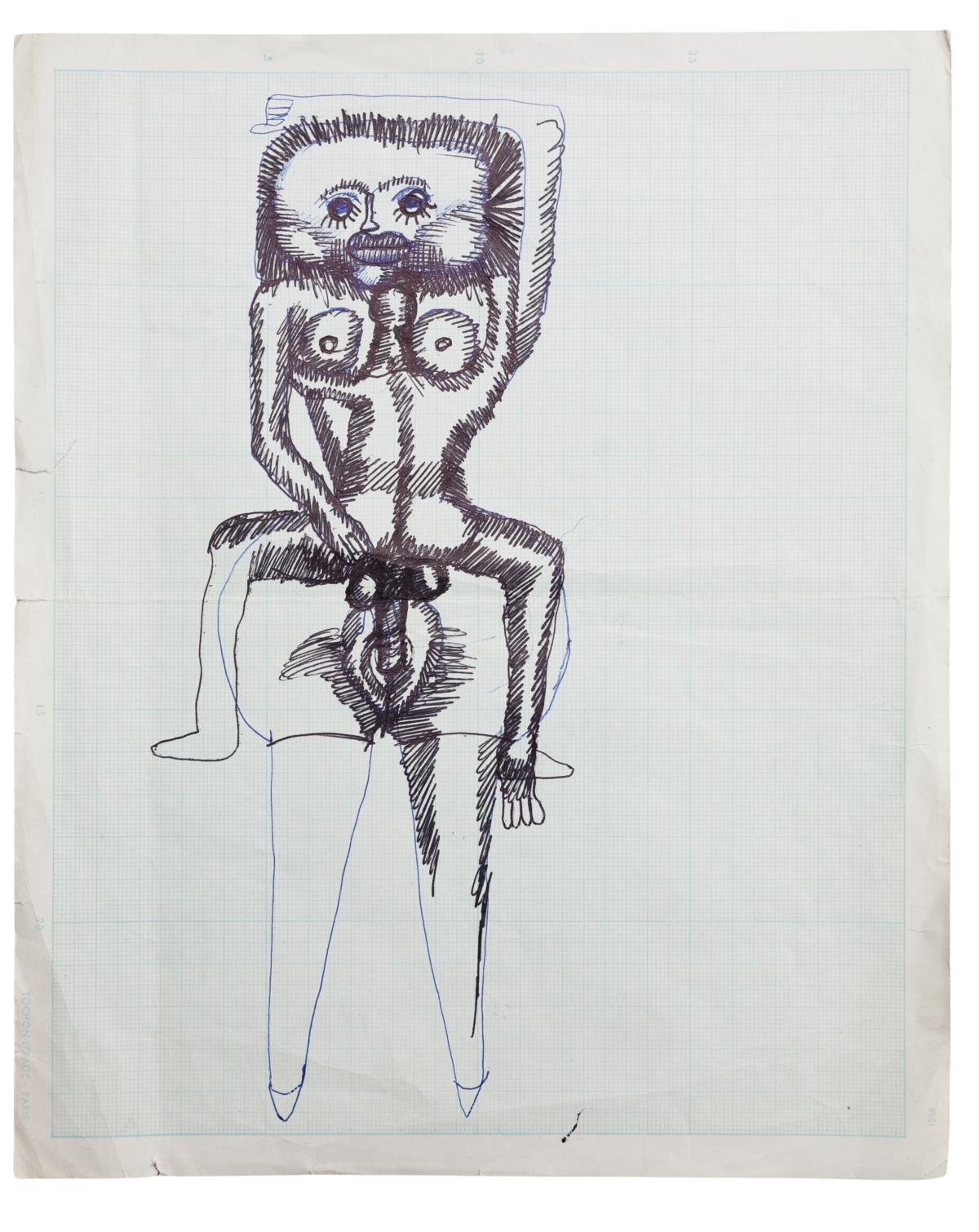

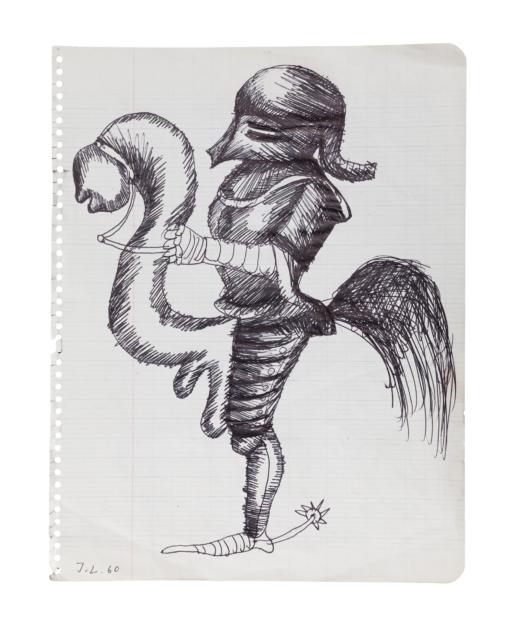

Why do we mention it? After all, one could be tempted to juxtapose this social and historical context with Jan Lebenstein’s works, especially his drawings, created in the privacy of his studio, and which have been included in the exhibition. Representations of women also appear in Lebenstein’s paintings, of course, but their images of canvas are usually “moderate”. Drawing is a very intimate technique. It does not require such focus of technique as painting, it is closer to the body. Looking at Lebeinstein’s works in 2020, one hears the call to examine the drawings independently and set aside for a moment the tools to analyse painting. Even if they seem to present the same thing. Many works presented at the exhibition are de facto pages from sketchbooks that have been mounted and framed. We can suppose that in such drawings, Lebenstein allowed himself to unlace the iconographic corset inspired by mythology, the Bible and great literary themes. The women here have a less obvious genotype, the connections with animals are surprising. Sometimes such a hybrid has bare breasts and is adorned in a halo at the same time. While the feminist perspective may be fundamentally suspicious of the male perception of the woman, who is usually nude in these drawings, it certainly does not exhaust the possibilities of interpretation. There is also often humour there, dark and not quite politically correct. The woman may have a rather old body, sometimes ugly, but at the same time these representations reveal sympathy, tenderness, a huge amount of intimacy, perhaps a desire for closeness. Unbridled imagination, humour and bold erotic representations open up the works. Literary narratives do not fit here, these are not totemic representations from the painting-like Axial Figures or simple interpretations of creating an image of a woman, whom the male eye only objectifies.

The drawings made in the private sphere, in the studio, often in sketchbooks, show women in an ambiguous way. Images of women, women-hybrids, break away from the mythological or biblical harness, opening up to a labyrinth of meanings without a defined centre. As an attempt to visualise drives, fascinations, fears, attempts at closeness, fetishisation, they attract with their mysteriousness and inaccessibility, but they can also repulse as a tasteless joke or an absurd excess of male imagination.

Initially, looking at the set of works selected for the exhibition, we thought about applying the key of domination – painting as power, transforming the body as a way to take over, absorb, subject it to one’s own rules, exercise control. The gaze of the painter – a man creating women, land and animals that are subordinate to him. Their presence is reduced to satisfying erotic and visual needs, but it is difficult to reconstruct their individuality, some other characteristics beyond servitude. The women are either nude, or their breasts, buttocks, vaginas and thighs are clearly delineated under their clothes. The female body remains in relationships with animals – the goat suckles at the breast, the bull tramples, the woman and the horse have a lot in common, the body of the woman as a victim or a child. The penis can simultaneously be the woman’s body, an animal (separate, attached), it can be a patriotic, hussar penis, the horse can reach its monstrously long penis with its head. The man is a half-animal, bull, serpent, he is beside her, looks at her, or penetrates her. We can, however, assume that the woman and the man are treated fairly equally. Their entanglement in corporeality, culture and archetypes remains similar. Well, perhaps the women are less hussar-like.

Untitled, 1960, ballpoint pen, paper, 22×17 cm

The text comes from the catalogue published on the occasion of the exhibition “Jan Lebenstein. Painting and drawing”, by Państwowa Galeria Sztuki in Sopot, 13.03-21.06 2020.

Photographs of the works courtesy of Maria and Marek Pilecki.

[1] Krzysztof Pomian, “Cielesność i historia” [in:] Jan Lebenstein. Rozmowy o sztuce własnej tradycji i współczesności, Andrzej Wat, Danuta Wróblewska [selection and editing], Krzysztof Pomian [introduction], Hotel Sztuki, Warsaw 2004, p. 21.

[2] Joanna Skoczylas, “Czy był artystą wyklęty”, Trybuna Ludu, no. 134, 1999 [in:] Jan Lebenstein i krytyka. Eseje, recenzje, wspomnienia, Andrzej Wat, Danuta Wróblewska [selection and editing], Joanna Sosnowska [introduction], Hotel sztuki, Warsaw 2004, p. 218.