The works presented within the exhibition Where Art Thou? pose a challenge to a viewer, a critic, but also to a curator. In my essay, I will hardly address the issue of art. Perhaps it will not be addressed at all in my analysis of the drawings and gouaches almost entirely created in the Warsaw Ghetto during the war. Instead, I will discuss their authors and the principles behind the selection of exhibits, as well as the status of the works themselves. Finally, I will describe what the reception of these works is or might possibly be.

Not many drawings and paintings from the Warsaw Ghetto have survived; after all, today, the traces of a few hundred thousand people who lived in the Ghetto are extremely scarce; their thoughts and emotions, and even the ordinary belongings are gone. What has been preserved, are the drawings, watercolors, and gouaches secured in the Ringelblum Archive and the works created by those very few people who survived the Holocaust. This collection is quite modest even if we compare it with the body of work created in the concentration camps.

When selecting the works, we moved within the area determined by place and time in search for the testimonies of that very moment and not the documents of the post-war reflection that constitute the overwhelming majority of art pieces related to the Holocaust. We tried to choose those drawings from the collection of the Jewish Historical Institute that to some extent addressed the boundary situations and thus the main theme of the exhibition. It was not an easy task: neither are the boundaries between those areas or rather depths of experience that unambiguous, nor is the scope we have at our disposal considerable. Even when we reached for the other collections – those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington or the Yad Vashem International Institute in Jerusalem – and decided to create faithful facsimiles of the originals. In fact, to finally select twenty-one works, I had to go through several consultations and changes on the way.

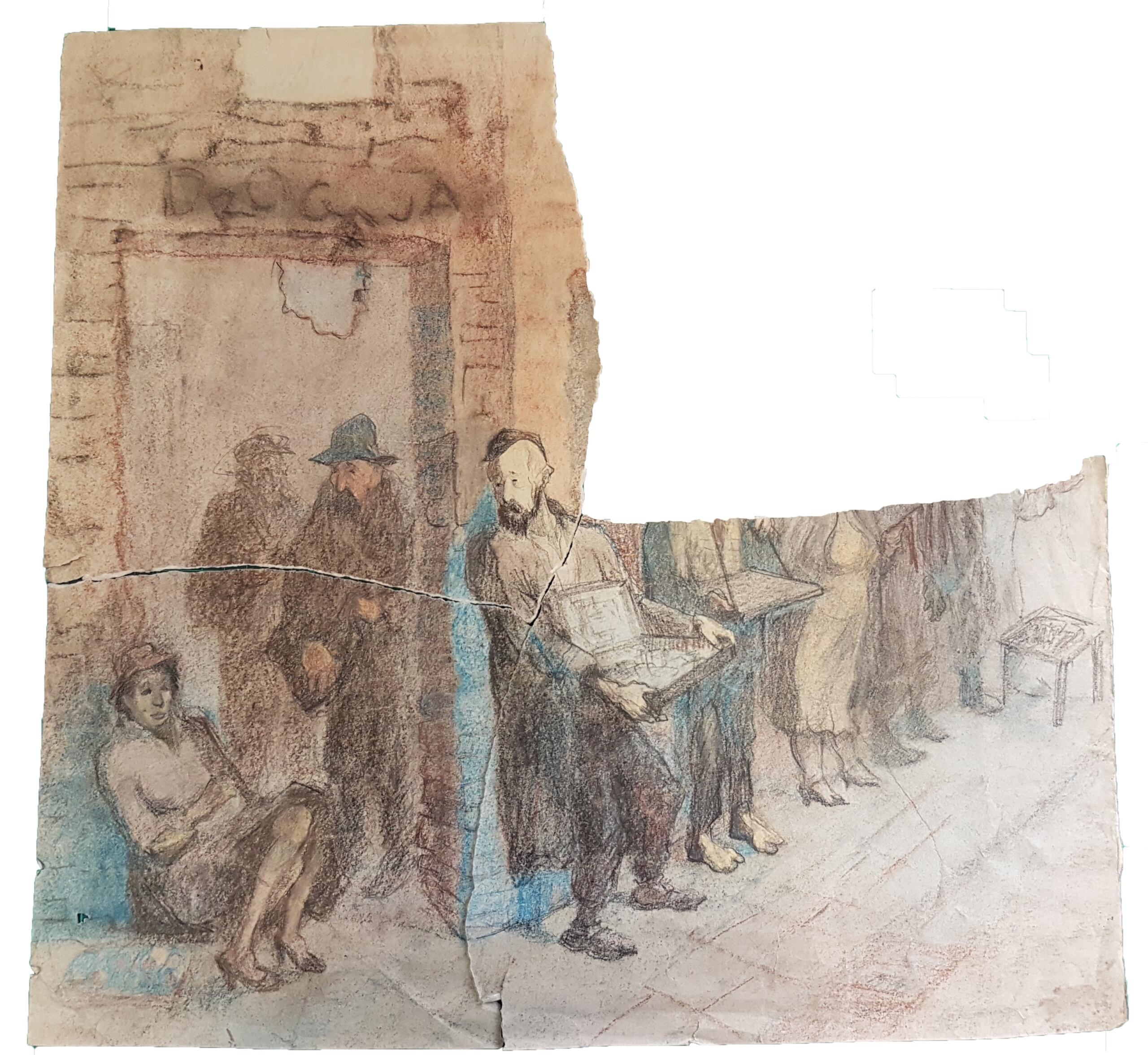

Krzysztof Henisz, ‘Street Vendors’ (undated), crayon, pastel, pencil on paper, 45,6×48 cm, Art Department of the JHI, MŻIH INW-A-137abc, courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute

Authors of the works presented within the exhibition

The album with drawings by Teofila Langnas, twenty-two drawings by Witold Lewinson, five drawings by Rozenfeld (today, we do not even know the name of this artist), and a few hundred works on paper created by Gela Seksztajn come from the archive gathered in the Ghetto by the Oneg Shabbat group. The drawings by Halina Ołomucka produced during the war survived together with their author. Such was also the case of some works by Langnas (later Reich-Ranicka). The drawings by the only non-Jewish artist in this group, Krzysztof Henisz, sketched during his visits in the closed district (or just after) were secured the same way. On the ‘Aryan’ side, survived the works by Roman Kramsztyk, although the artist himself was shot dead during the liquidation action of the Small Ghetto in August 1942.

Each of those artists became a subject of separate studies and all of them were commemorated to some extent, regardless of the aesthetical assessments of their works. In the following paper, it is not possible to dedicate much space to each of them[1]. Only one author from this group, Kramsztyk, was a well-known artist with a long career – and his sanguine drawing depicting the poor family in the Ghetto stands out for its artistry among the works presented in the exhibition[2]. Seksztajn, strongly associated with the Jewish artistic circles, worked as a professional artist in the 1930s; the Ringelblum Archive secured a few hundred works on paper created by her[3]. Henisz graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw before the war and he developed his art mainly in the afterwar period[4]. Lewinson also studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw[5]. Ołomucka and Reich-Ranicka (Langnas) took up studies already after the war; the former was probably an autodidact when she was creating in the Ghetto and then in the concentration camps, the later was said to have been taught drawing by Otton Axer still in the Ghetto. And about Rozenfeld, the author of bitter drawings with sharp, concise commentaries, we know literally nothing[6].

Therefore, among the artists, there are both the Holocaust victims and survivors. Six Polish Jews and one Pole. Each of them was stigmatized by the Warsaw Ghetto to a various extent. All of them left their testimonies.

Works

When selecting the works for the exhibition, and then discussing their diverse meanings and contexts, we tried to answer, sometimes not even consciously, many questions related to such crucial issues as authenticity and materiality of the work, its uniqueness, the author’s intentions, styles and codes applied, and finally, provenance, and thus, their fate. I used the expression ‘we tried’ since although the responsibility for the selection of works lied with the author of this text, it was also the subject of disputes, revisions, and modifications within our team. Therefore, when analyzing those works/documents, we used various classification matrixes; although such measures might seem somewhat insensitive, the entire conferences have been dedicated to them. Although all the aspects mentioned above belong to the scope of skills and competence typical for historians or art historians, the analysis of the testimonies from one of the most important epicenters of the Holocaust imposes exceptional methodological and ethical restrictions on the researchers.

‘Where Art Thou? Gen 3:9’, exhibition view at Jewish Historical Institute, photo: Jan Kriwol, courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute

The exhibition Where Art Thou? enters the extremely intimate territories, the sphere of boundary experiences, where helplessness of expression constantly clashes with shamelessness produced by reality. Together with the group of researchers from the Jewish Historical Institute, we carefully selected the testimonies of the horrifying, ruthless events that at the same time are still repeated and reproduced in various places all over the world. The exhibition involves archival materials related solely to the Warsaw Ghetto (and not for instance the ghettos in Łódź or Białystok) and created in the period between 1939 and 1943. They correspond with the included in the exhibition recorded voices of actors and actresses reading the words that were written during the Holocaust, and not later. The authenticity of the testimonies in this case is coherent with the immediacy, or putting it another way, the instantaneousness of a sketch; all the works from the Ghetto are the works on paper.

In her last will written during the Great Liquidation Action, when she was selecting the works that would be hidden in the box of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, she wrote: ‘I have to die, but I did my part. I would like to save the memory of my artworks.

The authenticity is what the physical features of those works are associated with – what kind of paper they were made on and what materials were applied, whether they are ‘rich’ or ‘poor’, but also how they survived. We ask different questions than those usually posed during restoration works, analysis of chemical components, and studying the physical structure of the object. One should not forget about the physical uniqueness of the testimony these works provide, often taken out of a metal milk churn or a box previously hidden in the debris of the Warsaw Ghetto, and with the implicit marks of death, fire, and decay intrinsic to those proofs, although the biological traces of life, even those of microbes, must have been removed from them during the disinfection process in the vacuum-sealed chamber.

Answers to those questions lead to attempts to make some presumptions on the status of the artists in the Ghetto, their access to materials, and finally, on the possibilities to rescue their works – and all these attempts carry a high risk of error. Yet another, often difficult, question is related to the date of creation of the drawings in the case of artists who survived the Ghetto, and then the concentration camps or the period of ‘vegetation’ in the hide-out on the ‘Aryan’ side. In such cases, we ask if this was a direct record, or a reminiscence. Is it physical evidence that after years, brings us, the judges and witnesses, closer to the real image of those events, or maybe rather a metaphor, a piece of fiction that links memory and emotions to transform them into specific forms of narration? The philosopher of history, Hayden White, addressing the writings and views by Primo Levi on the Holocaust literature, effectively undermines the division into facts and fiction by introducing the term of figural realism[7]. Those questions seem important in the case of works by Teofila Reich-Ranicka and Halina Ołomucka, for whom personal experiences of the Holocaust utterly determined the sense and purpose of creating art for the rest of their lives.

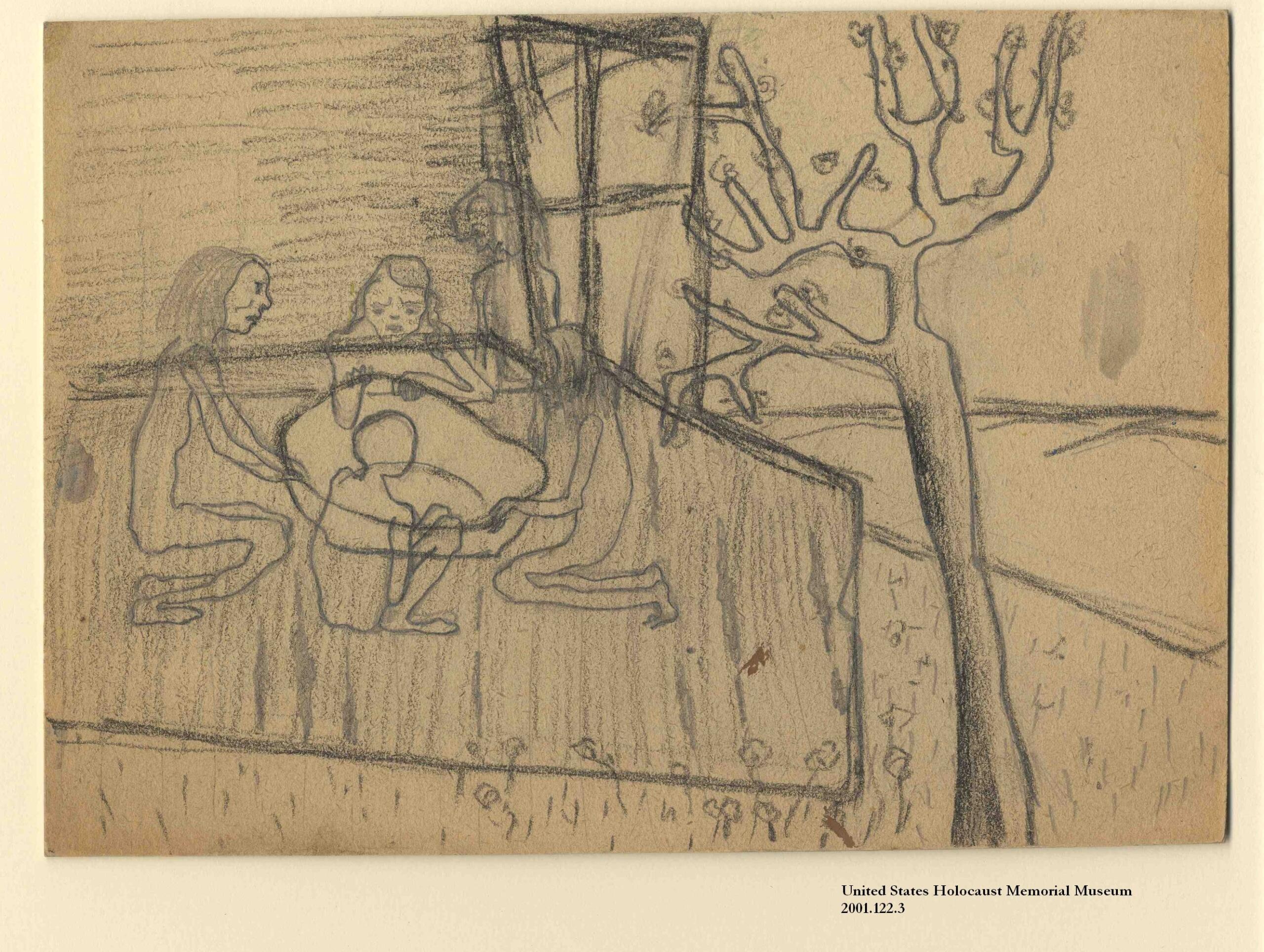

Halina Ołomucka, ‘Hunger’ (1942), pencil on paper, 21×29,4 cm, Collection of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2001.122.3, courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute

Those considerations lead to the question about the uniqueness of the testimonies from the Warsaw Ghetto. For authors, editors, and publishers of the books printed after the war and related to the Holocaust, ghettos, and concentration camps, it never seemed a problem to combine and juxtapose testimonies and records from various places, produced both by the victims and by the bystanders. Today, such practice could be perceived as flippancy, it would be questioned not only for the arguments related to credibility, but also for the ethical reasons, and the risk of unification and standardization of experience and memory. Having deep knowledge about the differences between the documents ‘from the Holocaust’ and ‘about the Holocaust’, we applied the principle of unity of place and time. The practice developed in the Jewish Historical Institute within the process of preparing subsequent exhibitions in the edifice that has survived the almost complete destruction of the buildings in the area of the Ghetto (and in face of ultimate erasing the traces of this architecture by developers today) commits us to working with exceptional diligence. And yet, the questions about the core difference between the drawings by Ołomucka or Reich-Ranicka from 1942 and 1946, still remain unanswered, as much as whether it would be legitimate to include Henryk Back’s drawings from the ‘Bunker of 1944’ cycle into our exhibition. Beck, a prominent physician and talented illustrator, after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising, together with a large group of people, was hiding in the bunker which was located in the area of the Little Ghetto, liquidated two years before. This story was inscribed in the narratives of the Warsaw Uprising and ‘Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw’. The bunker between Śliska and Sienna Streets, however, was a hide-out mostly for Jews, and among them, there was Beck, a Polish doctor of Jewish origin. Does the dark satire drawn by Beck, mainly in dramatic situations, differ in its essence from the works that were created (or could have been created) in the Ghetto?[8].

Not many drawings and paintings from the Warsaw Ghetto have survived; after all, today, the traces of a few hundred thousand people who lived in the Ghetto are extremely scarce; their thoughts and emotions, and even the ordinary belongings are gone.

The exceptional character of the drawings from the Ghetto is therefore defined by the place and time of their origin, as well as their authors’ intentions. And they were very diverse. Drawings served various purposes, and their authors applied different styles and conventions. For educational purposes, the Yad Vashem International Institute for Holocaust Research developed the classification of ‘the Holocaust art’; we can use some of these categories, although the typology proposed by the Institute does not exhaust the topic. Drawing ‘portraits’ and ‘art as a way to record’ are the most obvious activities for a person in a boundary situation; it is enough to look at thousands of people’s faces that were and still are perpetuated during wars, in camps, and in prisons. Sketched faces populate sheets of paper under the touch of Gela Seksztajn, Roman Kramsztyk, Halina Ołomucka, although each of them uses their gift to portray in a different way. In her portrait sketches and watercolors, Seksztajn tries to capture some characteristic features of the portrayed person; we can only guess which of them were created before the war, and which already in the Ghetto. In her last will written during the Great Liquidation Action, when she was selecting the works that would be hidden in the box of the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, she wrote: ‘I have to die, but I did my part. I would like to save the memory of my artworks. And also: ‘I am not asking for the accolade, but for preserving the memory of me and my daughter. This talented girl’s name is Margolit…’[9].

Hundreds of faces in the drawings by Ołomucka, both those created in the Ghetto and later; in Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Ravensbrück, Neustadt-Glewe, and then for her entire very creative life, hardly ever allow to recognize a specific person. They make an impression of peculiar and extraordinarily expressive l’écriture automatique, in which faces and silhouettes form a limitless and painful procession of memories. The creative act, the act of extracting images from the experienced moments and emotions seems to serve as a therapy, although it would be hard to use the term ‘fiction’ here and juxtapose it with the ‘documentary record’.

photo: courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute

Roman Kramsztyk, undoubtedly the artist with the highest artistic self-awareness from among this group of authors, drew his sanguine portraits with the virtuosity of the renaissance masters. But he also depicted the types of the Ghetto poor; we know two such drawings, the other ones most probably perished[10]. He was remembered as the person who ‘always liked sitting in cafes and so he did in the ghetto. He would sit by the window in a cafe in Rymarska or Elektoralna Streets just next to the border wall. With his artistic eyes, he observed smugglers gathering there and the fruit of these observations was a series of drawings presenting smugglers […] He was also interested in the types of Jewish paupers. He would draw whole groups of paupers hugging to warm themselves up and dead bodies that were a common sight in the ghetto. He believed that preserving this was his mission’[11]. Art here was used to convey the image of the poverty in the Ghetto, it gained a status of a record, of evidence. On the verge of death, Kramsztyk asked the painter who also happened to be the Order Police officer, Samuel Puterman, to promise him, that he would convince the other artists to paint the scenes from the Ghetto after the war. ‘Tell them that Kramsztyk asked them to paint the scenes of the Ghetto. Sacrifice everything, let the world know about the bestiality of the Germans’[12].

The authenticity is what the physical features of those works are associated with – what kind of paper they were made on and what materials were applied, whether they are ‘rich’ or ‘poor’, but also how they survived.

Sketches drawn by Krzysztof Henisz seem to be of a similar character – created on the spot, most probably during his visits in the Ghetto or just after; sometimes they were several versions depicting one and the same scene. Henisz’s drawings are the works of a witness, a bystander who can instantly depart from the closed district and find refuge in a moderately safe space. Nevertheless, this fact neither rejects their documentary credibility, nor their powerful expression; quite the contrary, the emotion of compassion seems to be enhanced by the entirely Polish witness from the script telling a story about the total extermination of Jews, written by the Germans.

The series of drawings by Witold Lewinson documenting hunger disease bears the status of evidence. If indeed the artist worked as a draftsman, such are his drawings depicting the effects of starvation with horrifying detailedness. He also authored the design of a poster called Child’s Dream (1942) which was a symbolic portrayal of the deprivation experienced by children in the Ghetto in terms of basic needs such as shelter, food, and warmth. When creating the poster and thus the work aimed at being shown in a public space, Lewinson reached for the modern artistic means typical for this genre in the 1930s, combining synthetic realism with the abstract, organic form. Yet another short series depicting abandoned children working as street vendors once again bears features of the documentary art, though full of compassion and sadness.

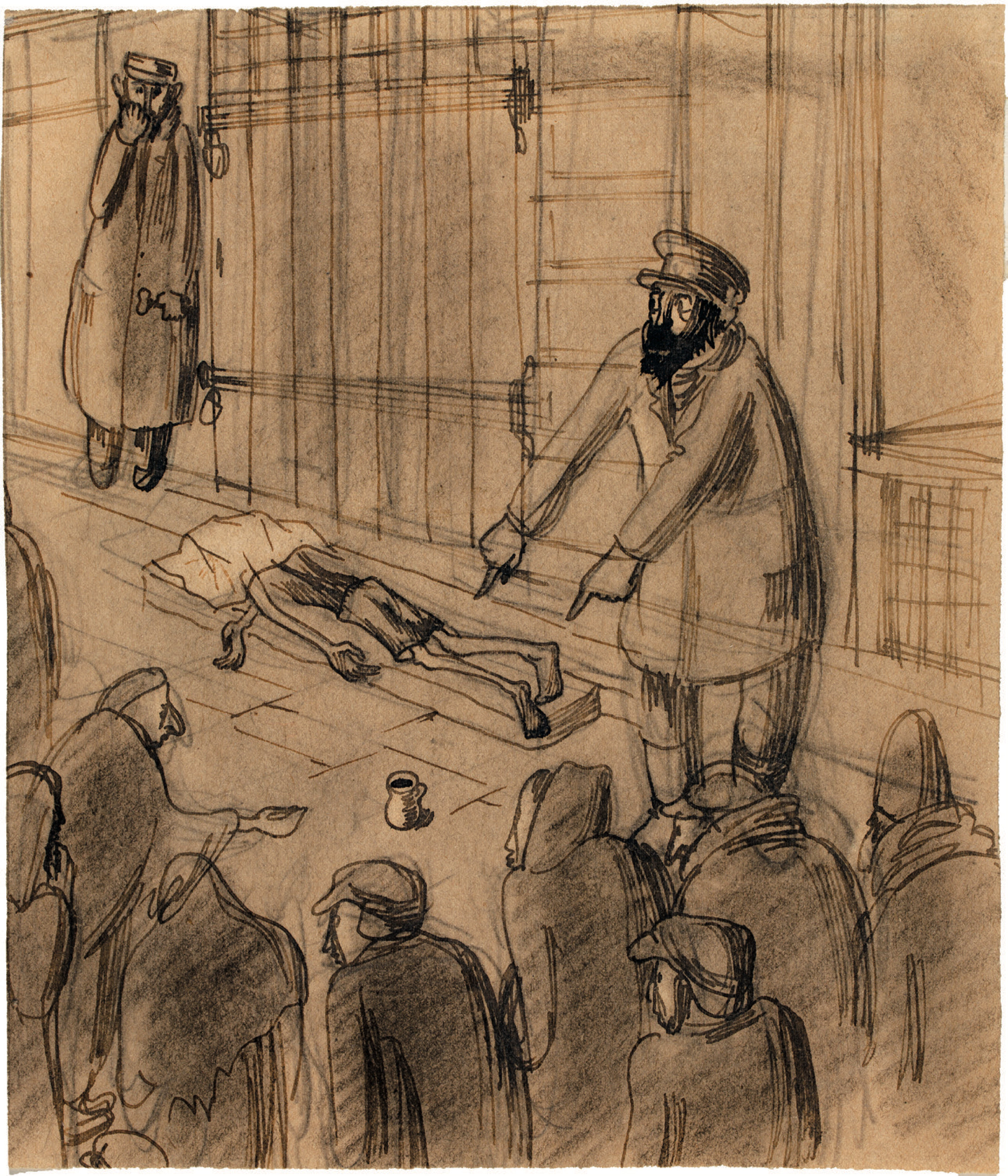

Benjamin Rozenfeld, ‘Funeral Fund’ (1941), pencil on paper, 20,9×17,8 cm, The Ringelblum Archive, the JHI, ARG I 581, courtesy of the Jewish Historical Archive

‘So what that our sense of humor is like a dance of skeletons’ – wrote Henryk Beck on two of his works from the black comedy series of drawings Bunker of 1944 (1944-1945)[13]. In the classification proposed by the Yad Vashem, various actors of the satire would most probably be included in the category called ‘Art as Means of Conveying’, although satirical drawing has not been considered there. Nonetheless, satire appears both in the Ghetto and concentration camps; in those most horrifying circumstances of constant danger, thanks to the satirical approach, people achieved the effect of a distance that allowed to depict situations, we often describe as ‘inconceivable’. Paweł Śpiewak wrote about it, discussing the problem of representing the Holocaust and speaking of its atrocities as either babbling or committing an act of sacrilege[14]. The drawing which depicts four people suffering from different diseases placed in one hospital bed originates in the exceptional Satirical Album on the Subject of the Activities of the Jewish Council (Album satyryczny na temat działalności Rady Żydowskiej, 1941) by Teofila Langnas[15].

We tried to choose those drawings from the collection of the Jewish Historical Institute that to some extent addressed the boundary situations and thus the main theme of the exhibition. It was not an easy task: neither are the boundaries between those areas or rather depths of experience that unambiguous, nor is the scope we have at our disposal considerable.

Langnas, after getting married in 1942, Reich-Ranicka, is also the author of one of the most commonly known series of works depicting scenes from the Warsaw Ghetto that have been exhibited and reprinted for several times. Some of those watercolors and gouaches were created still in the Ghetto, others most probably already after the war, and perhaps several years later. Over a dozen of her drawings, characteristic for their authenticity and powerful expression, were first time reprinted in the book by Jonasz Turkow published in Argentina; we do not know what happened to the original works[16]. In the subsequent versions of the series, created most probably after the war, the watercolors gain illustrative features, causing the effect of cognitive dissonance[17].

Evaluation of credibility, accuracy, and adequacy of the testimonies and records constitutes an extremely difficult and ethically risky task. Finally, it is time to address the series of drawings by Rozenfeld and thus the artist whom the Holocaust machine deprived even of his biography. For this reason, I know nothing about the author of those five particularly moving drawings. Each of them depicts an explicit scene, each of them is complemented by an authorial, sometimes quite a long commentary explaining the captured situation so that the people and circumstances involved did not remain anonymous. Piotr Żuchowski, studying the drawings, suggested that they might have been commissioned by the creators of the Ringelblum Archive. Rozenfeld might have not been a professional artist, but in his works, we can see the pulsating tension between the documentary record and derisive grotesque aimed at the perpetrators and co-perpetrators of the dramatic events (Little Smugglers, The Hospital on the Other Side). Even behind the drawing The Funeral Fund presented in our exhibition, there can be heard some sinister giggle.

‘Where Art Thou? Gen 3:9’, exhibition view at Jewish Historical Institute, photo: Jan Kriwol, courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute

What do those images want from us?

Paraphrasing the title of a famous book by W.J.T. Mitchel, an American prominent art historian working among others on the problems of reception and agency of images, I would like to finally address some issues related to the reception and meaning of the works from the Warsaw Ghetto. Their status is at least twofold – they are products of human artistic activity and at the same time remain records of atrocious reality organized by the Germans against a community of people whom they decided to lock away and determine their fate in the very center of a big city. As records, they fulfill a similar role to the documented testimonies, voices, and other traces from the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto. Their main purpose is to bear witness.

In the previously mentioned essay Figural Realism in Witness Literature, Hayden White indicated that many of those who witnessed the Holocaust were convinced that they were taking part in something ‘unbelievable’, that ‘many despaired of ever finding a voice or manner of writing that could compel belief in the veracity of what they had to say’[18]. The authors of the drawings from the Ghetto used such languages that they had at their disposal, and they did so very effectively.

However, we should bear in mind the difference between art and literature on the Holocaust and the direct testimony that comes from the inner circles of the Holocaust hell. The vast majority of literature on the subject belongs to the first group and thus written testimonies and records produced already when the mills of the Endlösung der Judenfrage machine had stopped. For this reason, looking at the images that had been created before the liquidation of the Ghetto, we do not see the absence and emptiness, we do not follow the almost invisible traces. Memory and representation remain in a rather direct, unmediated relation with one other, the same way as a sketch in a notebook or on a sheet of paper. The similar ‘instance of images’ in comparison to other narratives (that were the implication, the consequence) was mentioned by Cynthia Ozick[19]. Therefore, this is a different situation than the one defined by Dorota Głowacka as it follows: ‘Representation in the image, as understood by traditional aesthetics, allows for contemplative distance and mediation, which blunt the shock of the encounter with the Other’[20].

Bearing in mind the warning posed by Jerzy Jarniewicz in his Wstęp [Introduction] to the anthology entitled Reprezentacje Holokaustu [Representations of the Holocaust] that ‘no representation can do justice to the experience’[21], we should take into consideration and interpret the intentions that Krzysztof Henisz, Teofila Langnas, Witolda Lewinson, Halina Ołomucka, Rozenfeld, and Gela Seksztajn addressed to us.

The text first appeared in the catalog accompanying the exhibition Where Art Thou? Gen 3:9, presented at the Jewish Historical Institute from November 16, 2020 to April 25, 2021. The exhibition is curated by Paweł Śpiewak and Piotr Rypson.

[1] Most of the works created in the Warsaw Ghetto were gathered by M. Tranowska in the catalog Artyści żydowscy w Warszawie 1939–1945, Warsaw 2015.

[2] Literature on Kramsztyk’s art is very extensive; see the exhibition catalog Roman Kramsztyk, 1885–1942: wystawa monograficzna, luty–marzec 1997, Piątkowska T. and Tarnowska M., eds., Warsaw 1997.

[3] See the book dedicated to her, with the introduction by E. Bergman: Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy, vol. 4: Życie i twórczość Geli Seksztajn, Tarnowska M., ed., Warsaw, 2011.

[4] See: Nader L., Polish Bystanders to the Holocaust. Study into Examples from the Scope of Visual Arts – Preliminary Remarks, ‘Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały’, no. 14, 2018, pp. 185–195.

[5] See the note about the artist in Sztuka wszędzie: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie 1904–1944, exhibition design and catalog concept by Gola J., Sitkowska M., Szewczyk A., Warsaw 2012, p. 458.

[6] His works were described by P. Żuchowski, see ibid., Wstęp [Introduction], in Dziennik getta – rysunki. Z Podziemnego Archiwum Getta Warszawskiego / Ghetto diary – drawings. From the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archive (exhibition catalog), Warsaw, 2012, pp. 4–8.

[7] H.V. White, Figural Realism in Witness Literature, in Parallax, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 113–121; more on the subject in Muchowski J., Polityka pisarstwa historycznego. Refleksja teoretyczna Haydena White’a, Warsaw–Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2015, pp. 187–192.

[8] J. Jaworska, Henryka Becka „Bunkier 1944 roku”, Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1982.

[9] Archiwum Ringelbluma. Konspiracyjne Archiwum Getta Warszawy…, vol. 4, p. 19.

[10] M. Tarnowska, Artyści żydowscy w Warszawie…, fig. no. 121, 125.

[11] Recollected by Joanna Simon and her niece Halina Rothaub, see: ‘Tell Them to Paint Scenes from the Ghetto’. 128th birthday of Roman Kramsztyk, a painter and drawer, one of the most popular artists of the inter-war period, https://www.jhi.pl/en/blog/2013-08-18-tell-them-to-paint-scenes-from-the-ghetto (access: 01.11.2020).

[12] Ibidem.

[13] J. Jaworska, Henryka Becka „Bunkier…, pp. 36–37, fig. no. 43, 44.

[14] P. Śpiewak, Presenting the Unrepresentable, in Sztuka polska wobec Holokaustu / Polish art and the Holocaust (exhibition catalog), Bachur V., ed. Warsaw: Jewish Historical Institute, 2013, pp. 7–11.

[15] More on Album satyryczny by Langnas see: Rypson P., ‘Album satyryczny’ Teofili Reich w zbiorach Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, http://www.jhi.pl/blog/2020-06-01-album-satyryczny-teofili-reich-w-zbiorach-zydowskiego-instytutu-historycznego (available in Polish only, access: 01.11.2020).

[16] J. Turkow, Azoj iz es gewen [This Is How It Was], Buenos Aires 1948.

[17] T. Reich-Ranicki, H. Krall, Es war der letzte Augenblick. Leben im Warschauer Ghetto. Aquarelle von Teofila Reich, Stuttgart–München: DVA, 2000.

[18] H.V. White, Figural Realism in Witness Literature, in Parallax, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 114

[19] C. Ozick, The Rights of History and the Rights of Imagination, https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/cynthia-ozick/the-rights-of-history-and-the-rights-of-imagination/ (access: 01.11.2020)

[20] D. Głowacka, Disappearing Traces: Emmanuel Levinas, Ida Fink’s Literary Testimony, and Holocaust Art, in Between Ethics and Aesthetics. Crossing the Boundaries, New York: State University of New York Press, 2002, p. 112.

[21] J. Jarniewicz, Wstęp, in Reprezentacje Holokaustu…, p. 6.

Imprint

| Exhibition | Where Art Thou? Gen 3:9 |

| Place / venue | Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw, Poland |

| Dates | 16 November 2020 – 25 April 2021 |

| Curated by | Piotr Rypson, Paweł Śpiewak |

| Website | www.jhi.pl/ |

| Index | Jewish Historical Institute Paweł Śpiewak Piotr Rypson |