“For these ports I could not draw a route on the map or set a date for the landing. At times all I need is a brief glimpse, an opening in the midst of an incongruous landscape, a glint of lights in the fog, the dialogue of two passersby meeting in the crowd, and I think that, setting out from there, I will put together, piece by piece, the perfect city, made of fragments mixed with the rest, of instants separated by intervals, of signals one sends out, not knowing who receives them. If I tell you that the city toward which my journey tends is discontinuous in space and time, now scattered, now more condensed, you must not believe the search for it can stop. Perhaps while we speak, it is rising, scattered, within the confines of your empire; you can hunt for it, but only in the way I have said.”

– Italo Calvino “Invisible Cities”

Does a perfect city exist? One graced with majestic architecture and a touch of the right amount of melancholy, unforgettable to any traveller? Alternatively, it might be much more intriguing to plunge into the complexities of imperfect cities, those bustling with sinners, marked by decay, and bursting with untold stories. Every city, in its own unique way, harbours these dualities. They are cities of dreams and cities of fears, eternal cities and cities that have sprawled into oblivion. Others, though they may have shrivelled to a single street, continue to pulsate with life and history.

Vilnius serves as a fitting example – a city torn apart and tossed about by the forces of history, built and wrecked, its story echoing the turbulent narratives of countless other cities. It embodies the shared human experience of struggle, resilience, destruction, and regeneration. And yet, despite these commonalities, Vilnius maintains a distinct character, an identity that sets it apart, just as each city does in its own unique way. The art that truly encapsulates such an essence must be dynamic, mirroring the constant flux of the cityscape. It must acknowledge the urban dualities – the grandeur and decay. It must delve into the raw, unvarnished truth of urban existence, unmasking the beauty in imperfection. Perhaps this is the essence of the programme of the Vilnius Biennial of Performance Art, under the art direction of Neringa Bumblienė – a candid exploration of the multi-faceted, ever-changing, and beautifully imperfect nature of city life.

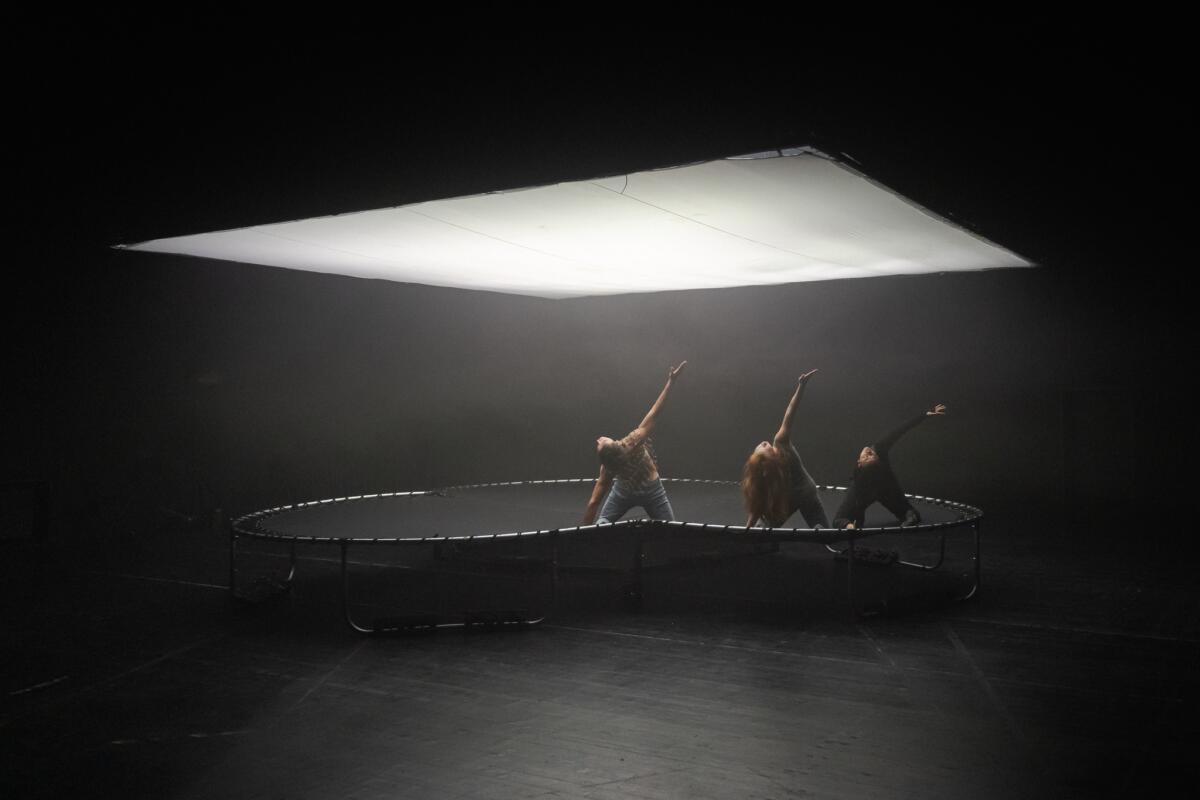

On July 23, the performance art piece “Song Sing Soil” by Eglė Budvytytė and Marija Olšauskaitė opened the biennial’s main programme and captivated audiences with its innovative use of the unique properties of a trampoline. This common playtime equipment was repurposed into a sophisticated tool, lending the performance a distinctive dynamic that imbued each movement with a sense of the otherworldly. Every leap, twirl, and tumble of the performers took on an ethereal quality, as though the laws of physics had been tweaked to mimic the gravitational pull of a different planet. The ease and fluidity of their manoeuvres were counterbalanced by the rigorous precision required to control the kinetic energy harnessed from the trampolines. The pinnacle of the performance was reached when the dancers’ bodies aligned, merging into a single entity that held an uncanny resemblance to a squid. This new entity was an empathetic expression of the contemporary human body, with each appendage embodying a distinctive aspect, together manifesting a coherent whole.

The soundscape that accompanied this spectacle was a soul-stirring tapestry of spoken words and music. Its lyrics unraveled like an ever-evolving internal monologue, confronting the audience with a mirror to their own fears, hopes, and desires. The power of this dialogue was in its intimate exploration of our shared human experience, delving into the depths of the subconscious mind, to unearth truths that often remained unspoken. Yet, the most captivating aspect of the performance might have been the parts of the dialogue that were not wholly human. These moments delved into a primal subconscious space that exists beyond societal norms, hinting at a raw, uncensored power that lay dormant within us all. These elements underscored the performance with a potent commentary on our potential as individuals and a collective, pushing the boundaries of what we understood about human interaction, emotion, and the possibility of metamorphosis.

The performance, titled “Gimbutas Street Band”, was a collaborative creation of Laima Kreivytė, Eileen Myles, and Justė Kostikovaitė. It was an intelligent, witty, and audacious presentation, envisioning a dialogue with the late Marija Gimbutas, an archeologist celebrated for her research on matristic societies of Neolithic Europe. The performance interrogated the conventions that dictated the male-centric nature of street names in Vilnius, prompting audiences to consider why so many thoroughfares were denoted by masculine terms or male figures. However, it’s worth noting that the selected discourse of “occupying” public space subtly employed the same masculine constructs they critiqued, an irony that did not seem lost on the creators. Despite labelling their work as a “comedic feminist spectacle”, Kreivytė, Myles, and Kostikovaitė did not shy away from engaging with complex ontological issues. They artfully provoked their audience with a question of universal significance: Could men and women truly empathize and relate equally with historical figures of any gender? Moreover, would Marija Gimbutas herself, the focus of the performance, have felt any discomfort at the notion of a street bearing the name of Jogaila, a male figure? Well, Morrissey sang “Now I know how Joan of Arc felt”…

The performance “A Guiding Light Part 2” by acclaimed artists Liam Gillick and Anton Vidokle unfolded at the historic railway turntable of the Train Repair Depot. It subtly coaxed the public into a realm of memory and identity with its deployment of familiar yet tantalizingly incomplete musical fragments. Played by five musicians perched on a rotating platform, the audience was swept up from the first few notes, recognizing the melodies but always left yearning for their completion. Like the satirical movie “Prova d’orchestra” (“Orchestra Rehearsal”, 1978) directed by Federico Fellini, it presented an organized chaos, a symphony of sounds and emotions that reflected the unpredictability of life itself. The rotating platform, reminiscent of a conductor’s podium, created an interesting dichotomy where the musicians themselves became conductors of their own narrative. The incomplete melodies, in their yearning for closure, echoed our collective experiences, ever shifting, ever evolving, and often left with loose ends. The audience, in recognizing these fragments, became part of this orchestral narrative, their reactions and interpretations adding another layer of depth and complexity to the performance.

The performance, particularly resonant with the Lithuanian public, cleverly incorporated strains of “Bunda jau Baltija” (“The Baltics Are Waking Up”) – a song steeped in revolutionary sentiment and broader, more inclusive regional identity. The artists’ choice of location, the railway turntable, held symbolic significance, designed to mirror the rotating movement of the top floor of the Vilnius Tower – a significant landmark in Lithuania’s fight for independence. The tower, historically a symbol of connection to the world and a means of disseminating both hopeful messages and desperate pleas for aid, lent the performance a poignant, historical resonance.

The performance functioned on a captivating, meta-artistic level, producing a layered piece of art within art – a tangible manifestation of the total theatre concept. The location was not just a backdrop for the performance, but also a film set where the audience’s reactions were captured. The spectators, thus, unknowingly became an integral part of the art, their reactions potentially as significant as the performance itself. In this way, the boundary between performer and observer was blurred, fostering a dynamic interaction between the two. It prompted an intriguing exploration of spectatorship, participation, and the inherent reciprocity within performance art. By potentially incorporating the audience’s responses into a filmic representation, Gillick and Vidokle challenged traditional notions of performance and viewership, making us reconsider the role of the observer in the creation of art. There are always two stages in the world – the public just doesn’t always realise they are also being recorded.

However, amid the solemn reflections of national identity, the spirit of revolution, and the power of music to evoke memories, the performance took an unexpectedly playful twist with the recurring first chords of the globally recognized earworm “Baby Shark”. This injection of pop culture, instantly familiar to the younger (toddler!) global generation, posed a tongue-in-cheek contrast to the traditional anthems of older generations. It raised the question: Had this tune become the new “conformist anti-revolutionary” anthem of this generation, one that has surpassed even national hymns in worldwide recognition? Gillick and Vidokle cleverly constructed the entire structure of the performance to perhaps mirror today’s soundbite culture, emblematic of the TikTok era and its ADHD media consumers. By offering a series of incomplete musical clips, the performance reflected our increasingly fragmented media consumption, challenging us to reassess our relationship with memory, identity, and the realities of our digital age.

Other artists featured in the biennial also ingeniously utilized the potentialities of film media. Performance art was traditionally considered a vehicle for artists to communicate with audiences through their bodies. However, sometimes an element of “possession” could make the message even more potent. This was evident in the performance piece “-lalia” by Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė, where the magnetic performer, Giulia Treminio, embodied the legendary figure Południca (Lady Midday) borrowed from Slavic folklore. The performance took place across two locations: it unfolded in the theater’s foyer while a live stream simultaneously broadcasted the action on stage. A surrealistic sensation enveloped the experience, making one question the nature of reality. Which experience was more authentic – watching the performance through a cinematic lens, which might offer a deeper insight into the conceptual framework, or experiencing the raw, palpable energy of sharing the same physical space with the performer? Treminio, effectively “possessed” by the artistic duo’s vision and the metaphorical spirit of Południca, found solace in the physicality of a sculpture by Stanislovas Kuzma. This gleaming figure became her alter ego, a counterpart to her darkness. Considering that Lady Midday is often perceived as the personification of a sunstroke, this performance masterfully employed collective subconsciousness to warn us of environmental hazards in a deeply creative way. “-lalia” by Gawęda and Kulbokaitė emerged as a compelling exploration of folklore, contemporary anxieties, and the nuances of spectatorship. The interplay between physical performance and digital projection, between possession and personification, painted a rich tapestry of layered meanings. Not every demon wishes you ill.

From an ontological perspective, technology is often seen as an extension of the human body. This idea forms the central exploration of Teo Ala-Ruona’s performance art piece “Enter Exude”. This premise has roots that trace back to iconic figures like Andy Warhol and Eduardo Paolozzi, who expressed their desires to become machines, reflecting a fascination with the merger of human and technological entities. Further pushing this concept, J. G. Ballard’s novel “Crash” presents a group of car-crash fetishists, finding erotic stimulation in staging and participating in car accidents. Their arousal is not derived merely from the mechanical act of crashing but also from their immersion in the technology of the vehicle, symbolizing a deeper human-technological synthesis. “Enter Exude” continues this conversation, probing the relationship between human and machine, self and other, and the organic and the synthetic.

Teo Ala-Ruona’s “Enter Exude” conjured a surreal, dysphoric sensation reminiscent of David Cronenberg’s 1983 movie “Videodrome”. In Cronenberg’s film, the physical boundaries between man and technology blur unsettlingly: a television screen appears to spill its electronic guts after being shot, while a man possesses a VHS tape slot in his stomach. These bizarre images articulate a visceral fear and fascination with the intermingling of flesh and machine. “Enter Exude” draws upon a similar sense of unease; disorientation to present its artistic narrative. Just as Cronenberg visually disrupted the barrier between organic and inorganic matter, Ala-Ruona’s performance disrupts our conventional understanding of the human body as a distinct entity separate from technology. A car, in this case, is not simply portrayed as a mechanical object, a means to an end, or a status symbol. Instead, it is transformed into a beautiful, shining entity that provokes a profound sense of desire. It is no longer a mere object; it transcends its inanimate status to become a companion, a family member, an extra limb, a sexual organ. Also the car, often stereotypically associated with masculine status and power, becomes a medium through which varied perceptions of masculinity are interpreted.

Keithy Kuuspu’s performance piece “False Falling” could be likened to a dramatic rendition of kabuki theatre, albeit set in an unconventional locale: a construction site. However, the intriguing concept and aesthetic failed to retain the attention of its audience, with only a third remaining until the end. The departing spectators also unwittingly became part of the performance themselves. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that in the current era, where people don’t even have the capacity to sit through “Barbie”, the audience’s retention rate may not necessarily be an accurate indicator of the value or merit of an art piece. However, this occurrence is worth noting, according to the creative team. It might suggest the need for a more engaging approach. The narrative seemed particularly hermetic, potentially alienating spectators not well-versed in its specific thematic language or context. Additionally, the rhythm of the performance appeared to be somewhat disjointed, which may have disrupted the audience’s immersion. These elements should be considered for future iterations, with a view to better maintaining audience engagement and fostering a more universally appealing experience.

The performance art pieces showcased in this year’s program appear to engage in a subliminal dialogue with each other, each resonating distinct thematic echoes. The performance “What Are the Dreams of Concrete?” by Eye Gymnastics, embodying the element of water through multiple voices, intriguingly resonates with the inaugural performance of the biennial, “Aphotia” by Emilija Škarnulytė, which took place earlier this year. “Song Sing Soil” by Eglė Budvytytė and Marija Olšauskaitė strikes a compelling conversation with “-lalia” by Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė, both delving into the captivating realm of darker spiritual authorities. Simultaneously, “My Body, This Paper, This Fire” by Pedro Barateiro and “Damascus, Copenhagen, Fetish Shop” by Adam Christensen discover a shared territory in the intimate retelling of personal experiences. Their works delve into the realm of personal narratives, using the canvas of their performances to recount deeply personal and subjective experiences. Simultaneously, “Still Standing” by Aleksandra Janus, Weronika Pelczyńska, and Monika Szpunar and “Throwing Balls at Night” by Jacopo Miliani draw inspiration from the past, specifically choreographic works of significant historical moments. The former piece pays homage to Israeli choreographer Noa Eshkol and her 1953 work created for the 10th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, while the latter revisits the 1913 ballet “Jeux”, composed by Claude Debussy for Sergei Diaghilev’s Paris-based “Ballets Russes”, with choreography by Kyiv-born ballet dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky.

In essence, this Biennial’s programme demonstrates an intriguing interconnectedness amongst its featured art pieces. It is as though each performance is a thread in a larger, more complex tapestry, exploring different themes yet somehow converging in a shared space of artistic dialogue. This underlying conversation enriches the viewer’s experience, allowing them to perceive the broader thematic links and deeper resonances between individual works. It’s akin to peering into various windows of a large apartment building, each room housing a unique narrative, yet these individual stories find a way to intertwine in the end.

The ingenuity of the Vilnius Biennial lies in this beautifully orchestrated symphony of diverse yet interconnected performances. And what makes this experience unique is its focus on urban existence. The programme encourages audiences not just to inhabit the city, but to truly “live” in it – to absorb its rhythm, to understand its narratives, and to acknowledge its influence on our collective consciousness. Each performance becomes a reflection of urban life, echoing its dynamism, its contradictions, and its constant evolution. These performances provoke introspection on what it means to be an active participant in the urban tapestry. They ask us to consider how we, as inhabitants, shape the city and, in turn, how the city shapes us. They remind us of our roles as both spectators and performers in this urban theatre. In essence, the programme of the Vilnius Biennial of Performance Art does more than just display a collection of performances, it opens a discourse on urban life, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation for our shared spaces. It is an invitation to engage more actively with our surroundings and to perceive the city not just as a backdrop, but as an integral part of our narratives, identities, and experiences.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Emilija Škarnulytė, Pedro Barateiro, Eglė Budvytytė and Marija Olšauskaitė, Adam Christensen, Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė, Liam Gillick and Anton Vidokle, Eye Gymnastics (Viktorija Damerell and Gailė Griciūtė), Kris Lemsalu, Robertas Narkus, Emilija Škarnulytė, Teo Ala-Ruona, BRUD (with Juan Pablo Villegas, Virginija Januškevičiūtė, Post Brothers, and others), a collaboration by Aleksandra Janus, Weronika Pelczyńska and Monika Szpunar, Rūta Junevičiūtė, Keithy Kuuspu, Jacopo Miliani, Pontus Pettersson, a collaboration by Justė Kostikovaitė, Laima Kreivytė and Eileen Myles, a collaboration by Yulia Krivic, Marta Romankiv and Weronika Zalewska |

| Exhibition | Vilnius Biennial for Performance Art |

| Place / venue | various public places |

| Dates | 23 July – 6 August 2023 |

| Curated by | Neringa Bumblienė |

| Index | Adam Christensen Aleksandra Janus Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė Eglė Budvytytė and Marija Olšauskaitė Eileen Myles Emilija Škarnulytė Eye Gymnastics (Viktorija Damerell and Gailė Griciūtė) Jacopo Miliani Juan Pablo Villegas Keithy Kuuspu Kris Lemsalu Laima Kreivytė Laima Kreivytė and Eileen Myles Liam Gillick and Anton Vidokle Marta Romankiv and Weronika Zalewska Monika Szpunar Neringa Bumblienė Pedro Barateiro Pontus Pettersson Post Brothers Robertas Narkus Rosana Lukauskaitė Rūta Junevičiūtė Teo Ala-Ruona Virginija Januškevičiūtė Weronika Pelczyńska Weronika Pelczyńska and Monika Szpunar Yulia Krivic |