Hic sunt leones

The upsurge of interest in early 20th-century avant-garde art in Central Europe in the late 1980s was inspired by a major book. Les Avant-gardes de l’Europe centrale: 1907–1927 (1988) by Krisztina Passuth, a Hungarian art historian based at the time in Berlin and Paris, was a pioneering and comprehensive work, based on many years of research on the region known as “Central” Europe. The geography of the region has been differently defined by each of the subsequent authors writing on the theme, depending on their perspectives, interests and biasses. Passuth emphasised the importance of the emergence and development after 1907 of various groups and movements associated with different centres such as the Prague and Budapest Eight, the Hungarian activists, the Polish Formists and the Czech Stubborn. Then she turned her attention to the impact of futurism, dadaism, the Berlin-based Sturm, Russian constructivism and the Dutch de Stijl, all of which played a part in the formation of Central European avant-gardes after 1920, with direct imitation of individual styles and models tending to precede deeper understanding and transformation. Passuth went on to consider the Hungarian avant-garde gathered around Ma, the Czech Devětsil, Zenith in Yugoslavia, the Polish constructivists and the Romanian avant-garde. At the end of her book she focused on the activities of Central European and East European artists living in the 1920s in Paris; in particular she assessed their participation in the L’Art d’aujourd’hui exhibition (1925). Krisztina Passuth’s book was aimed at French readers. It emphasised the unusual variety, as well as formal and intellectual contribution of the Central European avant-garde, whose initial phase in 1907 different dramatically from its end in 1927. She concentrated on artists and movements that significantly enlarge the model of the development of modern art. It was only years later that her book was translated into German and Hungarian.

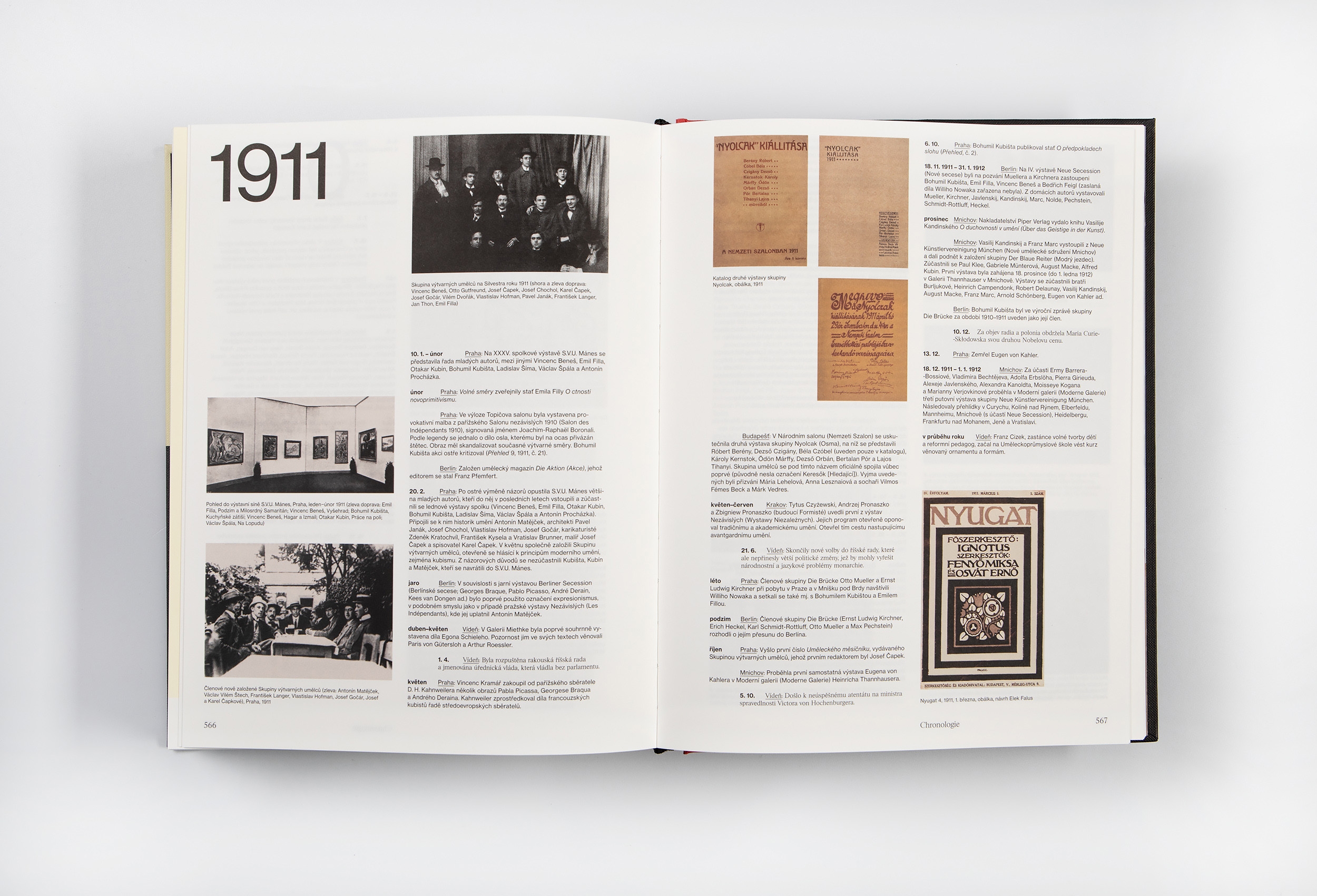

In the 1970s, research into Central European avant-gardes was largely neglected for political reasons. After a flurry of interest in the 1960s it was not until the late 1980s that art historians returned to the theme. It was then that the first synthetic surveys were published, mapping individual movements in Central Europe. They included books by Andrzej Turowski, Irina Subotić, Miroslav Lamač, František Šmejkal and Julia Szabo. These books became a source of inspiration for the young generation of art historians, but all dealt with the development of particular local avant-gardes. Krisztina Passuth, whose Budapest flat became a private study for all who were interested in this area of art, was the first art historian before 1989 to develop an original (and for a long time unsurpassed) analysis that emphasised the need for the integration of treatment of the art in these various geographical areas into the current model of modern art as developed by Western art historians. Passuth provided a powerful counterpoint to what was to be a series of exhibition and catalogue projects examining the relations between major centres. The first in the series had been held as early as 1966 by the rather low-key exhibition Paris Prague 1906–1930 at the Musée national d’Art moderne, to be followed by larger and more famous exhibition projects such as Paris – Moscow, Paris – Berlin and Berlin – Moscow, and quite recently by the exhibition Berlin – Vienna and continuing in exhibitions such as Budapest – Vienna or Budapest – Berlin. If for historians of earlier art the main watershed was the divide between South and North, represented by the Alps, study of art from the early nineteenth century onwards involved a shift of orientation to an East-West division, which became even more striking in the 20th century.

The title of Krisztina Passuth’s book indicated a concern with more than one generation of the avant-garde movement. In recent decades the term “interwar avant-garde” has come to prominence and even been adopted as a terminus technicus, but the word “avant-garde” had already been applied to art before 1914 in the period following the reception of Edvard Munch’s oeuvre, even though unlike their successors in the interwar period the artists of the time did not often use it themselves. This was why the founding generation of art historians of the avant-garde, who arrived on the scene at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, employed the term for the period 1907–1918 as well as for the post-war. The originally two-volume monograph by Miroslav Lamač and Jiří Padrta dedicated to the group Eight (Osma) and the Group of Visual Artists (Skupina výtvarných umělců) was called Founders of the Czech Avant-garde.

Since 1989 there have been many new books and exhibitions covering periods starting either before 1890 or in 1907–1910. Treatments in the first category have identified early points of departure for the avant-garde, such as when in late June 1855 Gustav Courbet, as a protest that his paintings were not included in the Salon, built a wooden shack and there exhibited his paintings during the Paris World Exhibition.[1] For treatments in the second category there could be no doubt that an avant-garde was defining itself in opposition to modernism well before the First World War, and of course even more vigorously after it, by which time it was an altogether different avant-garde. The first periodisation category is exemplified by the extensive researches of Steven Mansbach and Elizabeth Clegg, and the second by the work of Krisztina Passuth and Timothy Benson.

János Kmetty, ‘Kecskemét’, 1912, oil on canvas, 92×72 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and Hungarian National Gallery

No gearbox

The avant-garde was a group movement in art, whose members claimed that it offered a new programme for art, and a new outlook on art and life that defined itself against both earlier and concurrent movements. Yet it was far from being uniform or compact. It included contradictory, mutually exclusive stances and opinions. Although from the historical perspective it had an end as well as a beginning, its inspirations are still a living reality. In terms of avant-garde art history, the period 1907–1927 or 1908–1928 (depending on which is taken as the starting point, whether the arrival of the Prague Eight in 1907 or the establishment of the Hungarian Eight in 1908), was characterised by a number of common features manifest in most of the capitals of the lands of the Austria-Hungary both before and after the dissolution of the empire:

- After 1907 the avant-garde painters defined themselves sharply in opposition to academic artists and conservatives, including professors of painting at art schools. Many of them did not complete their own academic training, and most went to private schools. They formed their own groups and made their way as artists outside the established exhibition halls. Their original change of outlook happened under the strong impact of Edvard Munch’s work and under the influence of the three “maudit” painters: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Paul Cézanne. For a long time fluctuations in interest in one or other of these figures that determined the changing form of modern art. Similar groups were established in 1907–1908 in Prague, Vienna, Budapest and Krakow.

- Such generationally defined groups, consisting mainly of painters, tried to integrate themselves into existing art associations that had been established in the late nineteenth century, but found it difficult. The original founders of these associations were associated with impressionism, symbolism and Art Nouveau. Entry into art associations became a touchstone. Modernist associations or fellowships, which did not have a long history, already had their galleries and journals, exhibition juries and editorial boards, in which there were ferocious fights between the founders and the new artists who considered every exhibited or reproduced work a victory. Relations between the generations sometimes deteriorated to such an extent that younger artists left the associations and established their own. The main controversy surrounded the reception of cubism. After 1910 the membership in groups was no longer limited to painters and involved representatives of all contemporary areas of art.

- The First World War had a major impact on the reassessment of modern and avant-garde approaches. Many of their original representatives fell back on traditional forms of visual expression associated with lingering realism and the rise of neoclassicism. A rift followed, which in turn created a short-term concurrence between the original avant-garde and the newly arrived generation that declared itself a part of the avant-garde but actually understood this term differently from their predecessors who had originally broken away from modernism.

- The many artists who arrived on the art scene following the First World War developed the pre-war idea of the avant-garde as opposition to bourgeois culture, but added a rejection of its artistic principles, which they branded formalist and psychologising. Not even cubism, expressionism and futurism were exempted from critique. Only “lyricism” was spared. What was quite new was the boom of the left, spurred by the October Revolution in Russia in 1917. Art became the herald of changes in society, – the prefiguration of ideals to be fulfilled in the future. To be a representative of the avant-garde almost amounted to being a member of the Communist Party. The avant-garde thus acquired a pronounced ideological colouring that it had lacked prior to 1914.

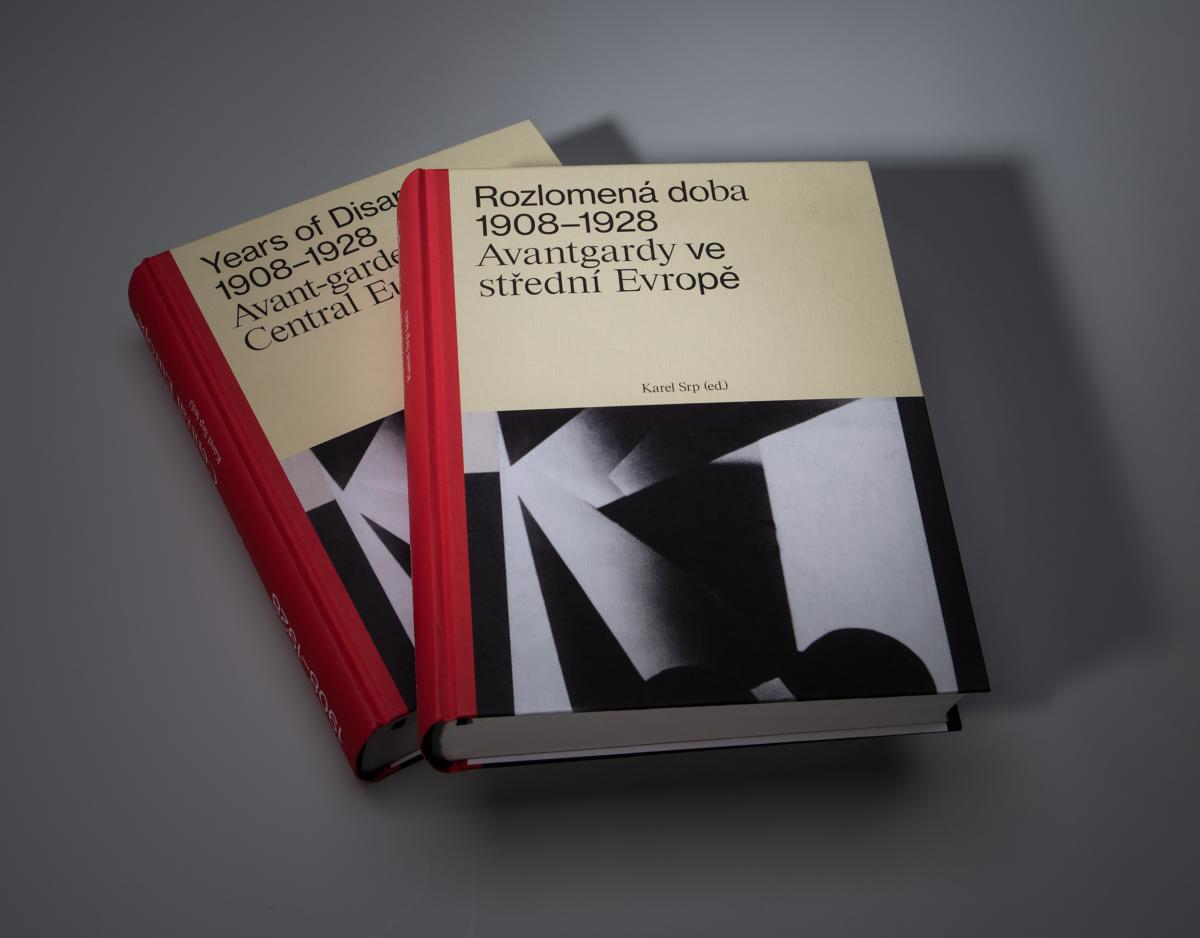

Years of Disarray ‘1908–1928. Avant-gardes in Central Europe’, edited by Karel Srp

Representatives of the avant-garde looked both to the future and the past. In the past they looked for solitary figures outside the official history of art. They saw such figures as pioneers and prophets whose messages had been rejected, misunderstood or disparaged in their own times. They re-evaluated the generally accepted model of art history, both before and after the First World War. Looking to the future, after 1918 they strove for change of the current order and the inauguration of a classless society. Over the years the number of avant-garde artists grew steeply. As an example, there were eight members of the Osma group in 1907, over ten members of the Group of Visual Artists in 1912 and around a hundred artists who were members of Devětsil in 1920–1931. International cooperation became the goal of the avant-garde as a group movement.

Modernism and avant-garde are very flexible terms, and much depends on the context in which they are used. We can distinguish at least three historical layers in which they have been deployed. The first is chronologically the original layer, in the years when individual artists were developing their practice and looking for a more general name to characterise it. The second is the historical-retrospective, appearing in books and articles considering the period from a distance of several years. Finally there are contemporary usages referring to the present with little or no relation to the earlier meanings of the terms. The second and third overlaying layers make it very hard to excavate the original meanings of the two terms. In any case, these terms were unstable even at the time of their origin, as each of the artists concerned used them differently. Overall, however, we can see a transformation in the relationship between modernism and the avant-garde. Initially, the avant-garde was the herald of modernism, a part of which it became, but then the two terms started to be defined against each other. In some contexts avant-garde was still a surrogate term for modernism with which it overlapped, and to make things even more complicated, the use of the two terms varied with geography, groups, and the focus of individual artists and authors.

Sometimes modernism and the avant-garde seem to be twins born in the mid-nineteenth century, whose growth was fed by the idea of progress and development and the need to differentiate the new from what went before, but even where they seem used in a broadly similar way as regards content, they were deployed in different areas. A good example of their overlap and difference is provided by an advertising leaflet for the third annual edition of ReD from 1929, which claimed to be “a monthly for modern culture” for “all modern people”, but also stated that ReD was “the only paper of the international avant-garde in Czechoslovakia”.[2] For Teige, modernism was above all a sharply delimited cultural area; it was the avant-garde of participation in an international movement. The inter-referential, at times overlapping or even identical terms of modernism and avant-garde did not mean that the two could not repel one another and turn one against the other, and the one did not imply nor condition the other. Each constructed its own domain. Modernism, when it arrived on the scene, had some features of the avant-garde but the same model did not apply vice versa. These two terms assessed one and the same art work from contrary perspectives. In contrast to modernism, which defined itself against tradition, the avant-garde asserted distance from any other art, traditional or not. Whatever its nature, traditional or non-traditional. This was mainly the case of dadaism, whose occasional forays into Central Europe disturbed all conventional values and undermined everything, including itself.

Vytautas Kairiūkštis, ‘Suprematic Composition’ (Suprematická kompozice), 1922–1923, oil on canvas, 38×31 cm, Lithuanian Art Museum, Vilnius

In 1999 after many years of meticulous research Steven A. Mansbach published a milestone book titled Modern Art in Eastern Europe. Subtitled From the Baltic to the Balkans, it was the second book, after Passuth’s, to examine this geographical area as a whole. Political developments had temporarily made Central Europe a fashionable subject among English and American curators and art historians who produced monographs and exhibitions on the subject. Steven Mansbach, as the first American researcher, explored some areas that had been neglected. His comprehensive survey of the many variants of modernity and the avant-garde in the years 1890–1939 in countries that after 1989 underwent a major geopolitical change caused by the disintegration of the Soviet bloc, created a notional new border between the East and the West, stretching between the Baltic and Adriatic seas. Although Mansbach focused on the eastern part of Central Europe, like Passuth he started his monograph with the Czech lands and closed it with Hungary. In between he considered Poland, Lithuania, the Baltic states (Latvia and Estonia), the south Balkans (countries of the former Yugoslavia such as Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia), Macedonia and Romania. With this concept, connecting Central and Eastern Europe (with the exception of Austria) he clearly filled an empty space in the canonical history of art. He made a major contribution to setting the record straight and refuting lingering prejudices about Central Europe’s insignificance. To pioneer this outlook required a great deal of energy and courage as an art historian. It revealed cracks in the model of the development of modern art favoured by Western culture, in which the primary division was between “Western” and “Eastern” Europe, while “Central” Europe was neglected, and regarded just as a transitional area between Paris and Moscow, marked on the map by the famous phrase hic sunt leones. Mansbach asked the crucial question of the relationship of modern artists to the states they lived in, first with regard to Austria-Hungary, including its Polish lands, mainly Galicia with Krakow and Lvov, and later to the new states that emerged after its disintegration.

Elizabeth Clegg took the same starting point as Mansbach in her lengthy highly structured monograph, Art, Design and Architecture in Central Europe 1890–1920 (2006), but while Mansbach had taken his account right up to the fateful year 1939, her end-point was 1920, at the point when the new geopolitical organisation of Central Europe was in place. Her thirty-year frame enabled her to map modernism as a matter of rising, intermingling waves spreading to cities such as Vienna, Prague, Krakow, Budapest, Zagreb, Ljubljana and Lvov, in which there were political and societal upheavals. There the modernist artists usually battled against the dominant folklorism and nationalisms, although these were occasionally reflected in local modernisms. The cities became knots that tightened when modern art found itself under threat and were loosened by controversies among its representatives.

The change in political climate after the disintegration of Austria-Hungary strongly influenced modern art and the avant-garde. Some representatives of pre-1914 modernism entered the service of the newly established states by contributing to their image abroad. Prior to 1914 there had been little direct relation between modern art and political representation except in Vienna, but after 1918 there was a significant change particularly evident in architecture. In this context a table of comparative development created by Teige in a 1933 monograph on Jaromír Krejcar to show Krejcar’s place in contemporary architecture in 1919–1930 is illuminating. Teige divided the table into five sections.[3] There were two main blocs: “West” and “USSR” and in between he situated Krejcar as the foremost representative of Central-European architecture with his designs for the marketplace in Žižkov, Prague, the Olympic department store and apartment house in Prague’s Spálená street, and a bath house in Trenčianské Teplice. The selection of individual examples went from the individual to the collective. The “West” was represented by Le Corbusier, Theo van Doesburg, Hannes Mayer, and the “USSR” by Tatlin, Vesnin and a collective residential bloc for engineers and scientists at the Ural steel mills in Sverdlovsk. In addition to this modern architecture, Teige included in his table two more sections: one was labeled “Czech official modernism”, represented by Pavel Janák and Josef Gočár, and the second by the area he called “beyond development”, which encompassed architecture “untouched by development”, inspired mainly by neoclassicism. For Teige, the terms modernism and avant-garde were often interchangeable. There was a similar situation in the other new states of Central Europe. In each of them two modernisms existed side by side: one, whose representatives were still linked with the state of art before 1914, and the other identified with artists born around 1900. In Czechoslovakia the first modernism took a meandering path from rondocubism through neoclassicist modernism to functionalism, while the second took the direct road from purism through constructivism to functionalism.

Years of Disarray ‘1908–1928. Avant-gardes in Central Europe’, edited by Karel Srp

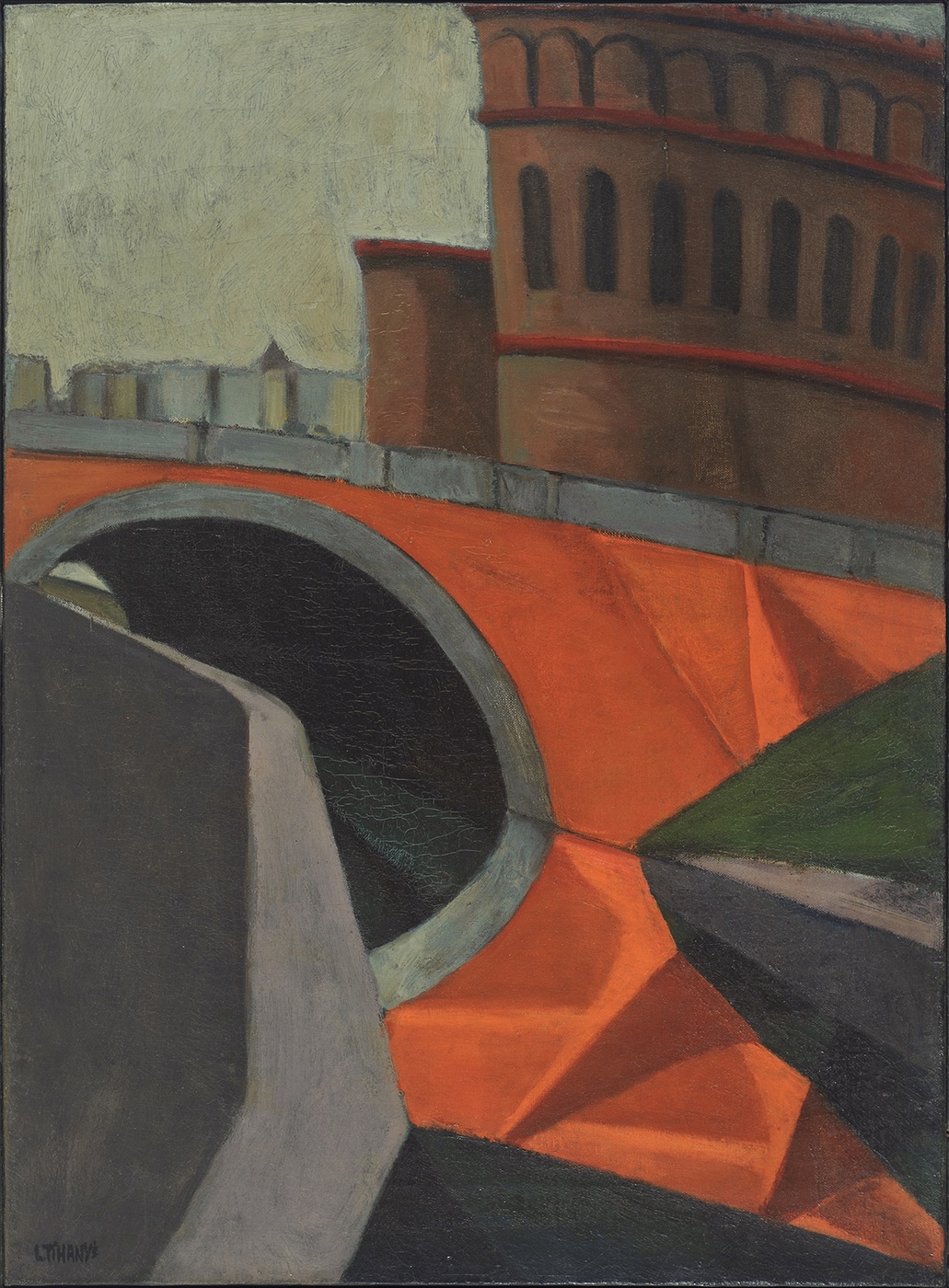

From the point of view of scholarship, national perspectives contrast with a broader focus on the cities with which the avant-garde was organically interlinked and whose names appeared in several forms thanks to changing state borders. In 2002, Timothy O. Benson and his team curated an exhibition for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art entitled Central European Avant-gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910–1930, accompanied by a large anthology of contemporary texts Between Worlds: A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-gardes, 1910–1930. The exhibition, with reprises in Munich and Berlin, mapped relationships between Prague, Budapest, Vienna, Weimar, Dessau, Bucharest, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Poznan, Krakow, Warsaw and Lodz. The list alone shows that the term “Central Europe” was fairly flexible, determined not by geographical considerations but historically, by the main avant-garde centres in the former Eastern Bloc. It was enlarged to include Warsaw, geographically outside Central Europe, and cities related to the Bauhaus (Weimar, Dessau), where many Central European artists worked as teachers or were based as students. A significant inclusion was that of Vienna after 1918, which could boast the unique pedagogical skills of Franz Cizek, and most of the representatives of the Hungarian avant-garde who fled there after falling out with the political direction of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The connection between the condition of art and the geopolitical layout of Central Europe was fairly loose. There was no direct link between the one and the other.

The protagonists of the avant-garde often developed their practice and positions at the price of great personal sacrifices and in the face of great misunderstanding, and they could find themselves at the very edge of society. Journals were the only sign that there were kindred approaches in the surrounding emptiness. The cities in which publishers of these journals lived became major avant-garde centres, wherever they were located in Central Europe. Metaphors used to describe relations between the individual avant-garde groups, included networks, fields or zones linked by fibres in the form of railways, airline routes, and radio waves. In Central Europe the density of these networks was exceptional, and since their historical mapping has depended so much on the choices of individual scholars, it has taken some time for a fuller picture to emerge. Slovakia, and specifically Košice, remained for a long time on the very margins of international research. In the 1920s, however, thanks partly to the influence of Josef Polák it became a major exhibition, lecture and educational centre. In 1928 this energy spilled over to Bratislava, where the School of Art Crafts was established and where some representatives of the Bauhaus later lectured.

Anton Jaszusch, ‘Power of the Sun’ (Síla slunce), 1922–1924, oil on canvas, 149×172 cm, Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava

Apollinaire × Kafka

The original foundations of modernity in the mid-19th century had involved avant-garde attitudes but in the late nineteenth century there was a visible rift between the modernist and the avant-garde. The difference between them was a matter of the life-art ratio, and became even more pronounced after the First World War, when the avant-garde turned entirely against modernism, questioned the very concept of art, and refused art in the name of life, with which it wanted art to merge, whereas the modernists still expressed life by a work of art, which they considered life’s highest fulfilment.

Czech novelist Milan Kundera has done much to provoke debate on the concept of Central Europe and modernity including the avant-garde, and so it is worth mentioning his interpretations here. In the context of the visual arts it is significant that Kundera was part of the honorary committee for the exhibition Europa Europa, subtitled Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarde in Mittel- und Osteuropa, held at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn in 1994. The main curators of the exhibition, Ryszard Stanisławski and Christoph Brockhaus, put on a ground-breaking show accompanied by a four-volume catalogue. The exhibition started from Central European symbolist painters such as Michal Vrubel, Witold Wojtkiewicz, Lajos Gulácsy, Rihard Jakopič or Mikalojus Čiurlionis, whose works could hardly be called avant-garde, but who were nonetheless harbingers of radical modernity.

Kundera had been developing his own concept of modernity since the mid-1960s, first of all in his introduction to a selection of Guillaume Apollinaire’s poetry and entitled The Big Utopia of Modern Poetry (Apollinaire and his legacy).[4] Apollinaire presided over the birth of the avant-garde movement in Paris, and after his premature death in 1918 the post-war avant-garde treated him as an icon and gave him his second life. He became a model, an inspiration not just for his great poem Zone and his calligrammes connecting word and picture, but also as an art critic and organiser of exhibitions. For Kundera Apollinaire epitomised the lyrical approach to the world that he himself rejected, questioned and treated with great irony in his novels. In Seventy-three Words Kundera spoke against lyricism as the avant-garde mode par excellence, and identified another, concurrently developing mode of modernity as a contrast and alternative.

On lyricism Kundera wrote, “There is a type of modern art which identifies with the modern world in lyrical ecstasy. Apollinaire. Exaltation of technology, fascination with future.”[5] As he noted, these features were already present in the Central European avant-gardes before 1914 and later they flourished in the former Czechoslovakia in the Devětsil group. Kundera outlined the reach of Apollinaire’s influence: “With Apollinaire and after him: Mayakovsky, Léger, the futurists, the avant-gardes.”[6] Kundera clearly conceived of the avant-garde as a part of modernism, and went on to sum up the complicated situation defined in Stanislav Kostka Neumann’s essential essay Open Windows, published in Lidové noviny on August 9, 1913. This essay followed up Apollinaire’s manifesto L’antitradition futuriste, which had come out as an independent leaflet on June 29, 1913. Neumann remarks that art lagged behind technological innovations, “Have you ever wondered why in the times of airplanes, cars, express trains and dreadnoughts, where everything fits into place and everything has a meaning, people want to impress the others by cultural activity?”[7] This was in his view a contradiction that could not be resolved. “Hey, boys, to the deck! Throw Picasso and Marinetti out of the doors, we don’t need them. We’ve had enough of apes. Our windows are open and through them we watch, listen, and have all our five senses to feel the categorical imperative of modern noise.”[8] In Open Windows Neumann did not hesitate to damn the most important representatives of modernism and the avant-garde, including Apollinaire’s close friend, the father of one of the major tendencies in art, parallel to cubism, and mentioned devotedly by Apollinaire alongside Picasso. Yet while Neumann opened the windows he kept the back door open, because he favoured the sensual dimension, filled with lyricism and not intellectual deliberation. He took the affirmation of senses directly from Apollinaire’s manifesto, which speaks of the “Plastique pure (5 sens)”, but in his view did not take sensualism far enough into new territory. Apollinaire’s view of the sensual became a major inspiration for Devětsil. Teige developed his ideas on “art for all” while Nezval searched for the “sixth sense”. Indeed, it is with Apollinaire’s and then Neumann’s concept of sensual nature that the avant-garde found its break-through moment. Neumann emphasised the unlimited flow of natural and technological beauty as the leading expression of lyricism. He rejected any scepticism of the kind that might ground a critical attitude to the sensual, which was something the avant-garde would not admit. Lyricism conceived of the senses as receiving impulses from the surrounding world, which were then interpreted by subjectivity, but neglected question of the limitations of the capacities of the senses, posed for example by the metaphor of the window frame.

Neumann was spurred to write Open Windows by Guillaume Apollinaire’s manifesto L’antitradition futuriste, published only a few weeks earlier. Apollinaire’s text was characterised by terseness and brevity, and its impact was strengthened by striking typography, suggesting that the manifesto was akin to typographic poems. The manifesto was a sensation. It inspired a similar article-cum-manifesto Image by Jindřich Štyrský, included in the very first issue of Disk in autumn 1923. In the conclusion of L’antitradition futuriste Apollinaire shockingly divided vocations,[9] movements and artists into those that were unacceptable to the avant-garde, and deserved “shit”, and admired up-and-coming artists to whom he would give a “rose”[10]. The latter meant principally Picasso and Marinetti, whom Neumann then ridiculed as “apes”. Yet Neumann was still actually building on Apollinaire’s sharp division when he concluded his Open Windows with lists of people under the categories “let live” and “let die”.[11] Teige’s Images and Pre-Images (1921) featured a similar dichotomy, in which some people were included under “yesterday’s horizon”, while others were called “great creators” with the comment that “today’s harvest grows under different signs”.[12] This provocative identification of sheep and goats, however, had a double impact: it created awareness of lesser known names of the new generation, and, at the same time, it resurrected interest in artists rejected by the avant-garde. Much depended on the way such productions were read.

Against Apollinaire’s modernity, which resonated right into the early 1930’s (see, for instance, the November issue of the second volume of ReD in 1928, in which Teige published a lengthy study Guillaume Apollinaire and His Times) Kundera posited a different face of modernism, which while less conspicuous at the time, likewise helped to create the culture of the time. “And on the opposite pole to Apollinaire there is Kafka. Modernism antilyrical, antiromantic, sceptical, critical.”[13]

Bohumil Kubišta, ‘Smoker (Autoportrait)’ 9 Kuřák), 1910, oil on canvas, 68×51 cm, National Gallery in Prague

In fact it was hardly the case that at the time the avant-garde ignored such aspects of modernism in favour of pure lyricism. Apollinaire was just one of the representatives of French literature to whom Devětsil paid attention. It is true that he had a huge impact on the development of Czech poetry, but Baudelaire, Lautréamont and Rimbaud were not neglected and were studied in the late 1920s by Teige, Nezval and Štyrský. In 1927, Teige wrote an afterword to Baudelaire’s La Fanfarlo, and then in 1929 to Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror; in 1930 Štyrský wrote a biographical monograph on Rimbaud, published alongside Nezval’s translation of his poetry. Kundera was of course right to highlight Apollinaire, whose impact on Czech poetry in the 1920s and subsequent decades was enormous, but the expansion of lyrical experience was countered by Lautréamont, whose vision of the world was sharper and more downbeat. Correctives to Apollinaire of the kind that Kundera finds in Kafka, who was only to be fully appreciated after the Second World War, at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, when the avant-garde was reevaluated as well, were manifestly present in others in the 1920s and early 1930s. The paradoxical phenomenon of antimodernist modernism, which “as the time flies gathers size”[14], involved artistic traffic with the other side. There were bridges between these two disparate and parallel worlds. In the poems of Richard Weiner, a writer who could be defined as one of the antimodernist modernists, we can find echoes of Apollinaire’s “zone”; in Jindřich Štyrský, who was one of the leading representatives of the avant-garde. Lautréamont was a major influence. All the same, the representatives of the avant-garde and antimodernist modernism had very different approaches to art. Kundera’s impressive, although artificial classification, can be transposed in visual art onto the relation between Kubišta and Filla, as it developed prior to the First World War. The difference between them is already evident in their subjectivity/style ratio: while in Kubišta’s work the style was based on supra-personal considerations, in Filla’s work it was the artist who created his own style. This makes Kubišta an exponent of antimodernist modernism and Filla an exponent of a lofty, immediate lyricism, manifesting itself in the creation of an infinite number of still lives. Kubišta impressed his contemporaries with his intricate compositional analyses, as is clear for example from the account of writer František Langer, a member of the Group of Visual Artists, who also intended to translate and publish some of Franz Kafka’s stories in Umělecký měsíčník. “When Kubišta, on one of his returns from Paris, drew on a marble café table Cézanne’s, Derain’s or Poussin’s compositions with lines, angles, intersections, diagonals and golden cuts, and proclaimed over them, like magic incantations or the new gospel, laws of order, forms, syntheses, artistic autonomy, depersonalisation, and timelessness, we surrendered and felt the ethos of the new art floating in our vague ideas on the essence of our verbal expression.”[15] In contrast to Kubišta, Filla approached his work spontaneously although he was developing cubism, whose meaning he grasped like no other in Central Europe at the time. Whereas Kubišta investigated the expressive possibilities of art that he took to the very edge of articulation, which for him was a “window frame” for entry into his creation, Filla stayed inside and never lost his belief in the bath of sensual impressions.

The Left × Communism

It was mainly politics that determined the relationship between the state and the artist. If in Austria-Hungary any view hostile to the emperor could be punished by prison or expulsion from school, after 1918 the main driver of the relationship was the variable attitude of individual states to the Soviet Union and the Communist Party, which was sometimes illegal in some countries. The first major controversy on the Left occurred during the short life of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919–1920. It was initially supported by a large number of artists of several generations, including the modernists and the avant-garde, but disputes with the Hungarian Soviet leader Béla Kun by no means all of them returned to Hungary in the late 1920s.

Although the terms communist and leftist were often interchangeable, the members of the interwar avant-garde differentiated between them. They did not hesitate to criticise the local communist parties or developments in the USSR from leftist principle. On the one hand, there were clashes with the Communist Party, which expected artists to adapt to its programme and to make comprehensible figural works of art for the masses that would communicate unequivocal ideological messages. On the other hand, there was a tension between the state power and left-oriented artists, as can be seen from the fate of the Croatian Ljubomir Micić, who for political reasons, had to move from city to city in the former Yugoslavia and ended up in Paris for several years. If the minorities of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy had felt nationally oppressed by Vienna, after 1918 the repression was sometimes even more severe, and all the more unbearable for being exercised by the new authorities of the supposedly liberated nations. Censorship was a continual hazard for nearly all the avant-garde Central European journals. It became quite commonplace for political developments to be the subject of direct comment by the main spokespersons of local avant-gardes. Paris was the only escape for most of free-thinking artists, both before 1914 and after 1918.

The avant-garde was not the characterised solely by passion for lyricism. After the First World War it became inextricably linked with leftist social and political vision. In the collection Seventy Three Words, Kundera tackled this aspect of the post-1918 avant-garde in his entry, “Modern (to be modern)”. As far as the voicing of political opinions was concerned, the post-war avant-garde went even further than its protagonists prior to 1914. It developed concepts of the end of art, while the anti-modernist modernists defended art by creating works that dealt with the very nature of their chosen genres. In this context the anti-modernist modernists made doubt the essence of their work, whereas the avant-gardes strove to transcend art in the name of life – the model offered to their contemporaries by Apollinaire and Neumann. The antimodernist modernists defended art from its own premises and as an end in itself, while the avant-gardes considered art useless. For the latter, modernity was identified with leftist ideology. Kundera quoted the conclusion of Vladislav Vančura’s preface to Jaroslav Seifert’s collection The City in Tears (1921), signed in its first edition only by the abbreviation U. S. Devětsil, which expressed the shared opinions of the new generation: “New, new, new is the star of communism. Its joint work builds a new style and there is no modernity beyond it.”[16] It was only later that Vančura admitted to having authored this text. Kundera used quotation from it to characterise a concept of modernity that was widespread after 1918, and went on to argue that as soon as communism lost its connection its demise began. Although Vančura in his preface wrote of the “order of new creation”, it is precisely here that Kundera sees the causes of decline: “The whole generation fled into the Communist Party in order not to miss being modern. The historical decline of communism was sealed from the moment it found itself everywhere outside modernity.”[17] Modernity was a condition, a measure of value that the Communist Party adopted temporarily in the first years of its exis-

tence, and whoever abandoned modernity found themselves looking into an abyss. Unlike the avant-garde, antimodernist modernism resisted the temptations of lyricism and communism, which Kundera seems almost to equate. It should be said, however, that in the 1920s there was still a distinction between the left and members of the Communist Party, and that this distinction became sharper in the 1930s, only to be all but erased after the Second World War.

Years of Disarray ‘1908–1928. Avant-gardes in Central Europe’, edited by Karel Srp

Paris × Moscow

In the years 1908–1928 Paris and Moscow were like the two poles of a magnet and they competed for influence in the wide space in between. Many Central European artists looked to them, and some even visited them and tried to succeed there. Whereas before the First World War the map of the Central European avant-garde had been shaped by the reception of cubism, constructivism shifted the geographical field significantly eastward.

The wave of energy set off before 1910 by the enthusiastic reception of Edvard Munch in Central Europe, inspiring painters to try to capture mental states in an illusionist idiom, continued until it came up against cubism, causing major rifts between advanced artists. Long-term open disputes were at the very heart of cubism; they mostly concerned attitudes to the founders of the movement and also the various possibilities of its adoption and development, which were no longer restricted to Paris. These disputes had an impact on the lives of many Central European artists living in Paris or dealing with cubism in Central Europe. Cubism caused a collision, and then fragmentation that then seemed to require the kind of larger synthesis at which Bohumil Kubišta arrived in 1913–15 with his “penetrism” – an attempt to connect the physical, intellectual and the spiritual on a nearly theosophical basis. Although penetrism remained only Kubišta’s personal opinion and somehow evaporated because of the First World War and the premature death of its originator in 1918, its echoes can be found among Devětsil members, including the poet Vítězslav Nezval and the writer Vladislav Vančura who occasionally used the term “penetration” or “gravitation”[18], under which Kubišta had summed up the inspirations of most pre-war art movements. Penetrism was the first clearly formulated modernist critique inside the avant-garde movement. The expansion of cubism was only halted by constructivism after the First World War which like cubism before it acquired a strong footing in Central Europe.

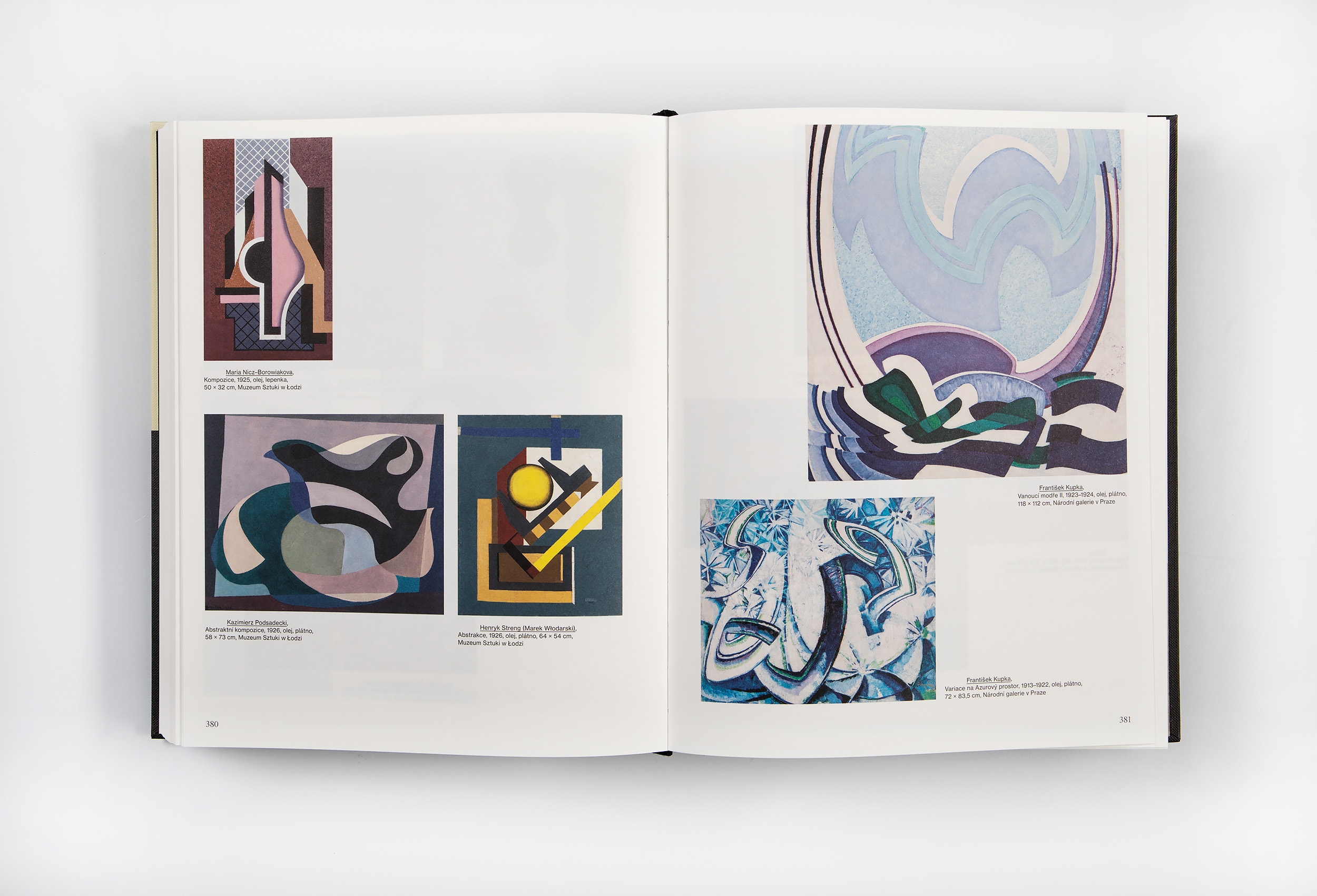

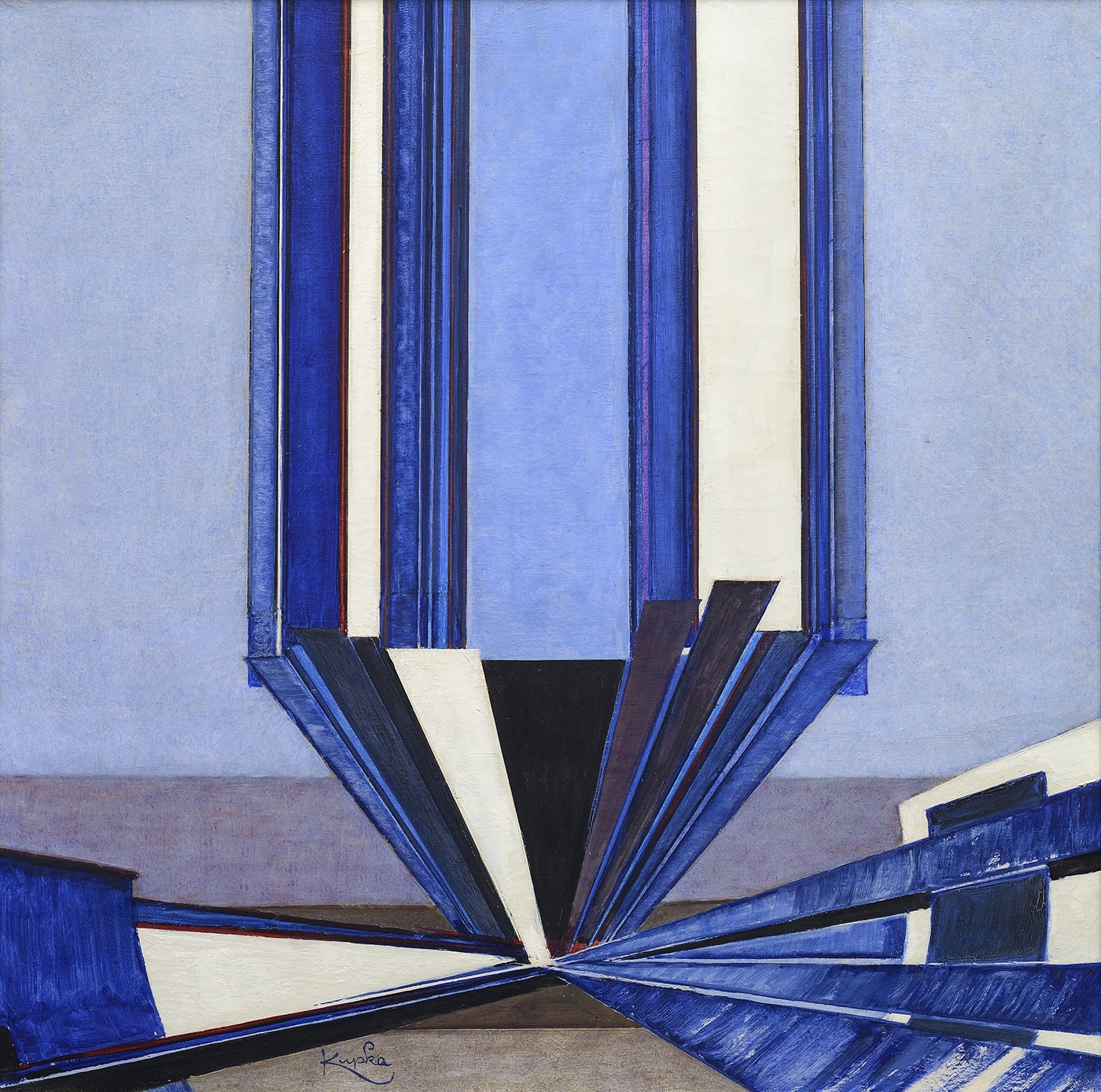

František Kupka, ‘The Shape of blue A II’ (Tvar modré A II), 1919–1924, oil on canvas, 68×68 cm, private collection

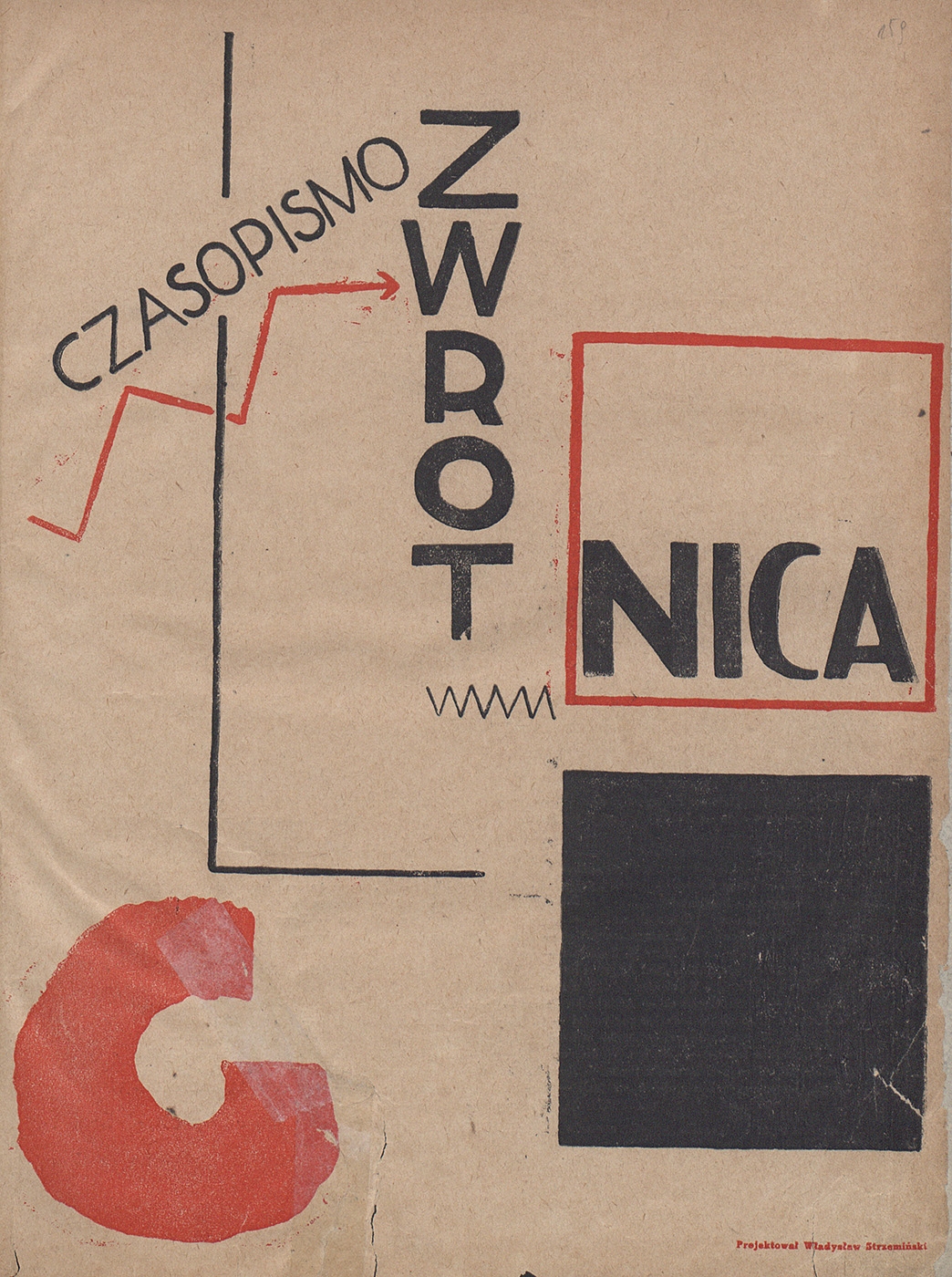

If cubism had its capital in Paris, constructivism’s capital was Moscow. Central Europe was permeated by the ideas of both movements, which spread from city to city and were widely discussed. Constructivist ideas travelled from place to place, were not limited to individual artists, and as it were wandered through Central Europe, often taking on meanings contrary to those they had possessed in the place of their origin. The exalted individualism of cubism was replaced by the collectivism of constructivism. If cubism was initially a form of personal expression developed by two painters who did not even name it as such and did not want it to become a widely transferable idiom in art, in constructivism the opposite was the case. Although its originators were occasionally mentioned, the language of constructivism was vigorously universalised and there were even conferences on the subject in the early 1920s. Originally, it was considered a programmatic expression of communist ideology. Constructivism quickly became the basis for the shared efforts of most Central European avant-gardes. While cubism was branded a formalist movement by its critics, in constructivism this was not seen as something negative. Constructivism concerned itself with purpose, machine production, simple assembly. In contrast to cubism, which maintained its distance from life, constructivism was intended to merge with the everyday. The representatives of constructivism focused on challenge to the hanging picture, as they wanted to apply constructivist principles not in exhibition halls, but in the surrounding world, architecture, objects of everyday use, typography, and posters. In hanging pictures constructivist ideas were transformed into geometric abstractions, and thus changed into the formalism for which cubism had already been rejected. Some justification for such pictures could be found by their association with architecture. This was suggested by the paintings of František Kupka, although he kept his distance from constructivism, and evident in the works of the German, Polish and Hungarian avant-garde, which contributed its own invention of “pictorial architecture”. The translation of constructivist principles into the hanging picture was nonetheless seen as dangerous and non-objective art was rejected. The communist left was critical of the works of László Moholy-Nagy, Władysław Strzemiński and František Foltýn. Model examples of the rift inside constructivism included the controversies inside the Polish Blok among artists affiliated with the Ma journal, and the opinions of the members of French communist party on Foltýn’s work. The radical left saw the hanging picture as a deplorable manifestation of art for art’s sake, even more deplorable when created by representatives of the avant-garde. Mieczysław Szczuka accused Władysław Strzemiński of working with pure form instead of focusing on a more comprehensible, politically engaged photomontage serving to promote communist ideas. Constructivism lost its meaning as soon as it turned into an art form. Inside the avant-garde there were two polarising wings with no bridge between them. An ever deeper gap opened up between art and political line.

‘Zwrotnica 1’, 1922–1923, cover, 29×23 cm, design: Władysław Strzemiński

From all directions

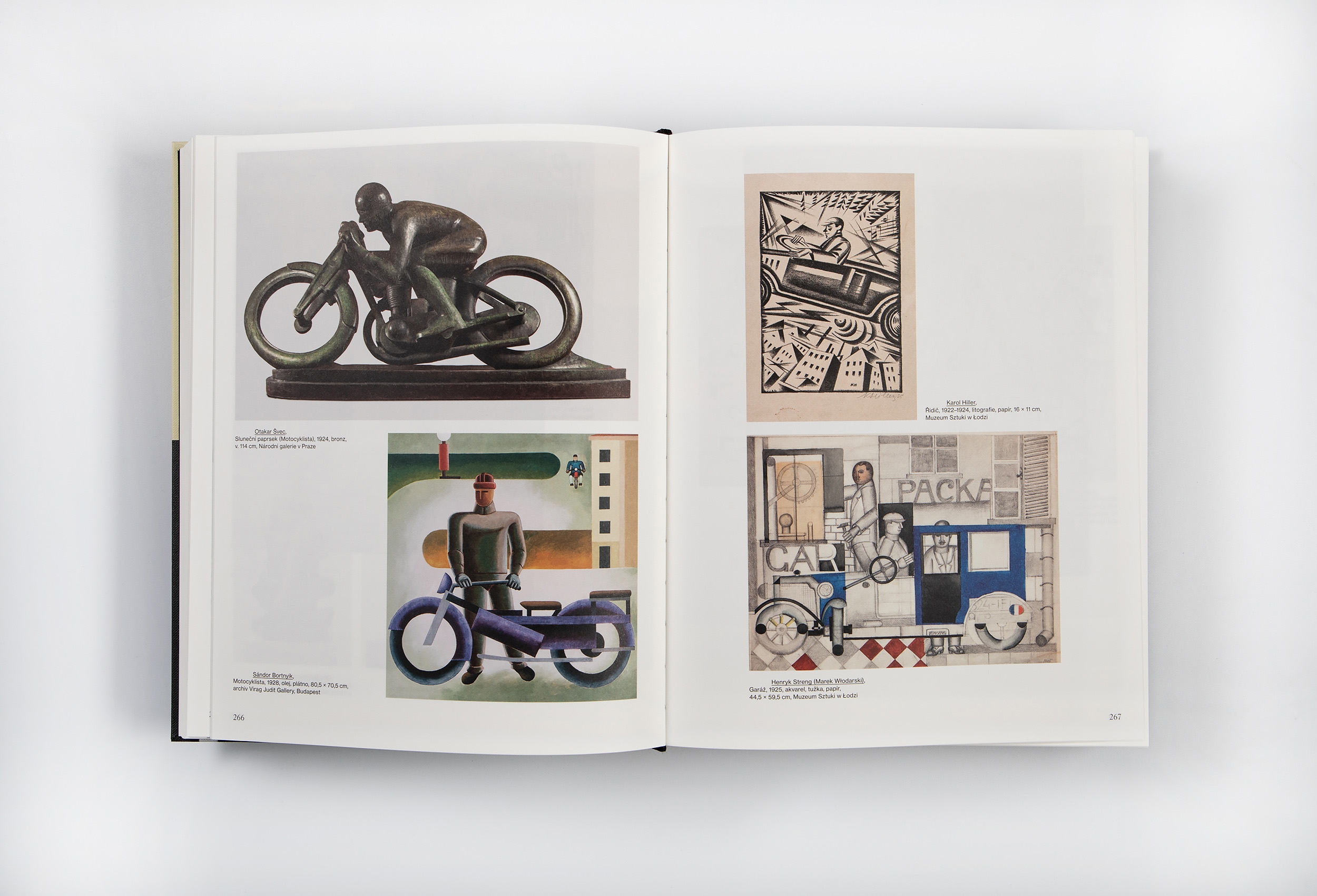

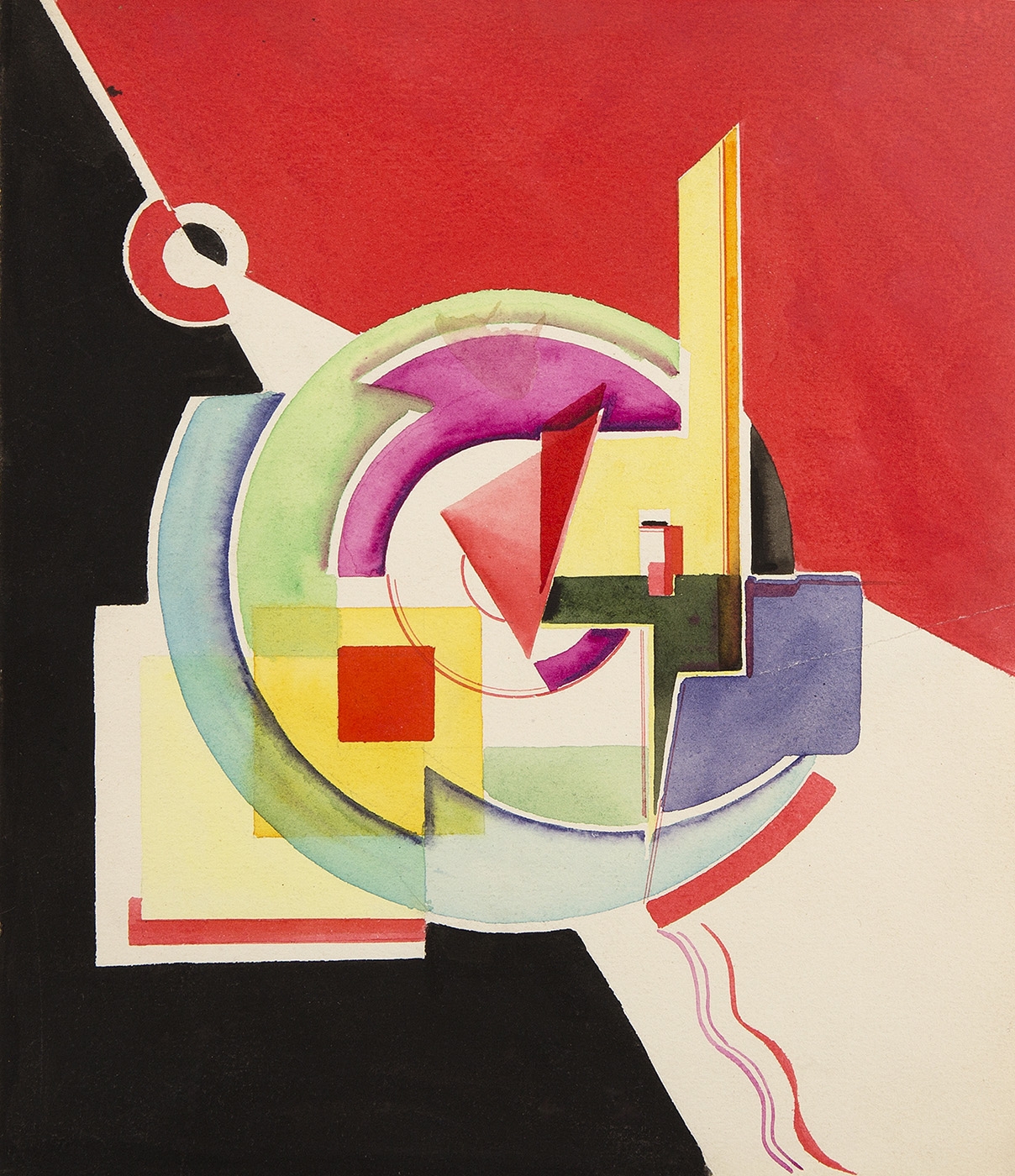

The polarity that became apparent after the war had already formed before it. On the one hand there was limitless belief in technological progress, which, oddly enough, became the driving force of lyricism, but on the other hand, there was the fear that this progress would strip man of humanity, oppress and devour him. Only occasionally did the diagonal deepening of space and the creation of an illusion of depth interfere with the orthogonal tendencies of cubism and constructivism. Central Europe was surrounded by futurism and there was no escape from it, and futurism called for all other forms of art to be taken by storm. It rejected the traditional and the historical, and even refused the term “art” as such. It showed all the characteristics of an avant-garde movement, although nationally coloured. It came not just from Italy, but from Paris, Berlin and Moscow. While cubism was restricted to the field of art, architecture and applied art, futurism had a potent energy that had an impact on every art form including theatre and music, and also involved fierce commentary on political issues.

Futurism developed across Central Europe more thoroughly and programmatically than cubism. While Neumann in Open Windows claimed to want to get rid of the representatives of both cubism and futurism – Picasso and Marinetti, he himself moved closer to futurism by promoting civilism (although in his case the relation was quite loose and concerned the machine). Teige understood futurism from the perspective of poetism when he claimed that it was intended to open eyes to a “lyrical conception of the world”[19], but expressed it in a distinct way, by dynamism and simultaneity.

In the late 1920s the avant-garde movement started to write its own history. To the 1929 February issue of ReD, published for the twentieth anniversary of the first futurist manifesto, (which had appeared on February 20, 1909, on the title page of Le Figaro), Teige contributed a lengthy essay emphasising the relationship of futurism to politics and criticising futurism from the perspective of constructivism. Futurism had been the single movement in art proclaiming, long before the outbreak of the First World War, that it was necessary for Austria-Hungary to cease to exist. Teige noted that in 1914 the futurists had “demanded that Austria-Hungary be destroyed“[20] and had called on Italy to enter the war. Marinetti lauded war as the only hygiene of the world, praised militarism and attacked Austria-Hungary, whose destruction the futurists then considered their own achievement.”[21] A change of political direction came after the war when Marinetti embraced the potential for the ideological development of futurism in tandem with fascism, in the book Futurism and Fascism (1923), which Teige challenged.

While Teige considered the bonding of futurism and fascism to be a deviation, he saw positive potential in the relationship between futurism and constructivism. As late as 1929 he still failed to see that communism was as dangerous for art as fascism, under which, after many decades in Italy, “traditional false neoclassicism”[22] prevailed. In this context we should point out a certain revival earlier futurist elements in constructivism. For example, the motif of a triangle penetrating a circle appeared in the statement of the futurists after the outbreak of the war (Sintesi futurista della guerra [The Futurist Synthesis of the War] on September 20, 1914) and was later repeated, in colour, in a similar futurist statement after the end of the war (Sintesi della guerra mondiale [A Synthesis of the World War] of September 20, 1918), in which a red triangle penetrated a green circle. El Lissitzky then founded his 1920 poster Klinom krasnym bej belych (Stab a Red Wedge into the Whites), which has a clear ideological bias, on a similar configuration and in the same militant spirit. In fact, this shared ideologisation of basic geometric shapes did not mean that futurism and constructivism really converged. Although they spoke against art as such, the futurists maintained their belief in autonomous artistic creation rather than art as the servant of the needs of life. The futurist manifesto of November 1922, written by Enrico Prampolini, Ivo Pannaggi and Vinicio Paladini L’arte meccanica, was a eulogy to the machine, but Teige rejected any hint of machinism, writing, “The form of the machine is wholly subordinate to purpose and the spirit of a machine is not an exact fulfilment of function. Let us repeat: the machine belongs in the factory and not in a poem or picture.”[23] Attitude to the machine became a major topic influencing many discussions in the mid-1920s. According to Teige, the futurist attitude to purpose was stuck at the halfway mark: “The purists and constructivists have a worked out relationship to the machine. The futurists today seem to be getting very close to constructivism.“[24]

Milko Bambič, ‘Broadcasting’ (Vysílání), 1926, watercolour, paper, 19,4×22,5 cm, Goriški muzej Kromberk, Nova Gorica

Lyricism and Neologisms

The pictorial poem is considered to be one of the major contributions of Devětsil to the Central European avant-garde. It was a poem created by the combination of various techniques such as watercolour, collage, photography, and typography. It was intended to replace the hanging picture. The pictorial poem was supposed to have a certain unifying theme. Often it was about departure for distant countries, and involved ships, flags, names of ocean liners or destinations. Devětsil considered the pictorial poem to be one of the purest expressions of lyricism. The motifs were reduced to the two dimensional, and mixed up, looking like double exposures, involving simultaneity of action and fast alternation of contrasting sources. Although the generation of the rising post-war avant-garde tried to shake off the immediate heritage of art prior to 1914, considering it passé as far as development was concerned, there had been some foreshadowing of aspects of the picture poem before the war. One example is the painting Le Port (1913) by Félix Del Marle,[25] which contains all the features of the future pictorial poems, if still delivered in a partially cubist-futurist form. The technique, of course, was different, since in the later work oil painting was replaced by more attractive, more ambiguous techniques using reproduction.

One of the ideas that were part and parcel of constructivism was the development of an international language – a universally understandable, visually accessible code that would replace all current languages, and on which pictorial poems could be based. It had to be a matter of simple neologism, like signals, flags or traffic signs. Morse code or Esperanto became models. The more universal and objective this language was, the more it was free of psychologism and personal meanings. The effort to develop such a code was most significantly manifest in typography and architecture, in which the differences of personal contributions were partially erased without the artist and his approach or convictions vanishing entirely behind the work. In functionalism we see a transition from constructivist declarations and purely visual experiment to actions with an impact on everyday life. Its basic features were anonymity and universal comprehensibility. It manifested itself in objects of everyday use, such as the chairs made out of bent steel piping, developed concurrently in 1926–1927 by Mart Stam, Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe. These chairs gave the impression of objects without an author, even though their authorship was recorded and confirmed by patent.[26] The pragmatic, depersonalised shape hid an exalted subjectivism. A seemingly nameless product was the result of deep individual reflection on the meaning of form. In functionalism all the premises of constructivism were fulfilled: new material, machine production, standardisation, typification, purposefulness, simplicity, and immediate comprehensibility. The development of a common language was made possible by bent steel pipes. The chair became a model new shape, for no such chair had been made before. The Bauhaus’s impulses were developed by Jindřich Halabala, who disseminated the common language in Central Europe. In his essay The Machine and the Type, published in 1930 in Světozor, attacked the tradition of suspicion of machine production, from Luddism during the industrial revolution (which was the subject of Béla Uitz’s prints in the early 1920s graphics by Béla Uitz) right up to the most recent expressions of fear that the machine would devour human individuality. In functionalism the machine was considered to serve, not to dominate, so long as its relationship to its user, whom it was to serve, was properly understood. Halabala rejected the idea that the machine might become a source of overproduction, and so allegedly a cause of the economic crisis. In Halabala’s view machine production ensured wide availability of products. “With their perfection, the machines give us more, they belong to all who have come to terms with machines and help to employ them. The frequent decrease of prices… means only that the machines have given us more again.”[27] Functionalism was closely related to economics. The attitude of antimodernist modernists to the machine was quite the contrary; they saw it as something that devoured and enslaved humanity.

Years of Disarray ‘1908–1928. Avant-gardes in Central Europe’, edited by Karel Srp

Lyricism was one of the principal sources of the avant-garde. Avant-garde lyricism pervaded everything. When Teige summed up Le Corbusier’s two Prague lectures in an article in ReD in September 1928 as the “technical essence of lyricism”, he emphasised that Le Corbusier “articulated unequivocally the principles of the concrete construction that has brought a revolution into established construction forms… and he even said that lyricism, the highest value of mankind, could bloom only on the exact and precise basis of technology. Architecture thus conceived can be defined as poetry, a poem created by scientific methods with the help of all technological devices.”[28] Le Corbusier had expressed an opinion long promoted by Teige, which was that lyricism was not just a quality of written poems but pervaded a concrete skeleton or steel construction in everyday reality. Lyricism could be perceived in simple geometrical shapes such as the circle. Neumann’s vision, developed by Teige, that art should progress to the level of modern technology without representing it, could only be realised only through the lyricisation of the world, elevating all the inventions of the modern period. Following the construction of the Eiffel Tower the new steel structures had featured as motifs in works of art much more frequently than concrete skeletons, which came to be called lyrical only many years later. When the Eiffel Tower became a commonplace, it was replaced by steel constructions. This shift can be observed in the work of Josef Šíma. The Eiffel Tower is visible in the background of the poetic figural works of the first years of his Paris stay, but in 1926 it was replaced by the striking steel structure of a transport bridge built as early as 1905 by engineer Ferdinand Arnodin in Marseille.[29] Lyricism named the world, penetrated everyday reality, and made chairs out of bent steel pipes. The international language of new shapes, communicating via signals, included the emotional value emphasised by Nezval in his Parrot on the Motorcycle. This was a text halfway between a poem and a poetic programme which was published together with Teige’s poetism in the holiday issue of Host in 1924. In it we find the words, “Emotions. Maximum of emotions per second. No description. A summary idea: a spotlight with impact. A blow in sleep that awakes the dream. A march like in a dream. From the impact to particularities. A light point that disturbed the water surface.”[30] Maximum excitement was to be concentrated in a single point resembling a sudden vision, unattainable by a description of spiritual movements or the analysis of social relations. Lyricism was immanent in construction, and not a value added from the outside.

While Le Corbusier lectured in Prague, new shapes were being investigated in Paris by Jindřich Štyrský and Toyen, who came up with their own movement called artificialism. As their point of departure they took the dominant post-cubist morphology, but used it to create new shapes that enlarged the principles of an international language by the addition of personal inputs referring to nature and memories. Their lyricism, on the very edge of individual expression, was emotive. The goal of the new shape-signal was bring to life the unconscious contents hidden in the spectator’s mind.

Apollinaire’s L’antitradition futuriste included a call for the “invention de mots”, which is something that Kurt Schwitters eventually took up in his performative Ursonata (1922–1923), involving the recitation of sound neologisms before these were established as words. These neologisms were not necessarily successful immediately. One of them was “Czechoslovakia”,which denoted a state that did not exist at the time of Apollinaire’s manifesto. The artificiality of this combination is referred to by Milan Kundera in Seventy-three Words, where he said that he did not use it in his novels, because it was too young and not tested by time, and therefore it could not be called beautiful. It was a merely schematic designation of the area, and Kundera preferred the much older, although objectively incorrect name.[31] He had several reasons for it but essentially it was because the name Bohemia still retained its poetry. There was indeed a major dispute between the avant-gardists, promoting their own neologisms, and the pioneers of antimodernist modernism, who found poetry in older words.

Antimodernist modernism pursued themes that lyricism refused to accept, such as identity, alienation, doubling, the many indices of anxiety, sadness, absurdity, sarcasms and ironies undermining the sense of the single direction of progress and belief in the future just ordering of society. Whenever a hint of death and awareness of death appears in lyricism, it is just a moment in the course of the world, immediately replaced by other ideas related to the beauties of life. In antimodernist modernism, it is followed through into the darkness of self-destruction. The avant-garde and antimodernist modernism existed side by side but had contrary goals. Whereas the first was a utopian ideal of the classless society promoted by constructivism, the latter was a vision of apocalyptic doom without the possibility of resurrection. On the one hand, there was an idea of the shared project of perfecting mankind, but on the other the prophecy of self-destructive decline ending in personal doom. Contrary ideas grew from the shared culture of Central Europe. They can be regarded as the obverse and reverse of a mutually interconnected plane, the most apt example of which might be the planar geometrical shape of Klein bottle, where it is impossible to tell the inside from the outside. The antimodernist modernist spoke mainly for himself, without any regard to his surroundings, and only sometimes with a view to publication of his work. The avant-gardist spoke for his group, which had self-promotion directly written into in its programme.

The research of Passuth, Mansbach, Benson and Clegg has shown the need to define and explore themes that transcend the borders of states, towns, directions or movements, associated groups and artists conceived as defining themselves against each other. Also important are the intersections and interconnections existing outside programme directions and isms, mutual relations of intermingling and the migration of styles, concerns and motifs from artist to artist, place to place, without regard for their sense of belonging. These manifested themselves in ever denser intersections, as also in sharp edges and gaps without any apparent immediate continuity.

In recent decades the art history of the 19th and 20th centuries has largely become the history of modernism and the avant-garde. One layer of possible interpretation has therefore been emphasised and given priority over others, and all the art created in a particular period has been viewed through one prism, thereby sidelining a great deal of it. In the process, the modernist and avant-garde legacy has as it were liberated itself from its time and period context. On the one hand, we can investigate modernism and the avant-garde in ever greater historical detail, providing an ever more accurate picture of personal relations. On the other, we can look directly at these works and see that they still offer an exceptional experience, shift ways of seeing, and retain their potency as revolt against established perception, resistance to everything past, critique of an ossified society, i.e. still have an impact as an articulation of the new. Works that undermined their time retain this energy even a hundred years after their creation.

Lajos Tihanyi, ‘The Bridge’ (Most), 1921, oil on canvas, 74,8×54,9 cm, Galerie Berinson, Berlin

The individual × society

It is tempting to generalise from one’s personal opinion, formed from the reading of exalted, unique novels, and to conceive of the whole of Central Europe as a place in which sadness and spleen has manifested itself more strongly than anywhere else. Milan Kundera offered the laconic description – “Central Europe, the laboratory of twilight”.[32] The metaphor, connecting a natural phenomenon and a place of experimentation, became the eye of a maelstrom, that devoured much more than the lyrical Epicureanism of the avant-garde. The illusion of twilight was suggested by the planetarium, crowning the idea of a universe comprehensible as a whole, which was made possible by the perfection of Zeiss’s projection machine. Planetariums spread throughout Germany in the 1920s and made their way to Central Europe only later.

Photographs of men assembling the dome of the Jena planetarium designed by architect Walther Bauersfeld remind me of the efforts of art historians to tie up the loose ends of individual lines of development and to define their meanings. These documentary photographs fascinated the main representatives of the avant-garde, who reprinted them in their books. For example Karel Teige included one in an anthology of international architecture published in the spring of 1929 to accompany Werner Graeff’s article on Industrial Construction Methods[33], and it was the penultimate image chosen for his book From Material to Architecture (Von Material zu Architektur; 1929) by László Moholy-Nagy, who accompanied it with the commentary: “The new period of inhabiting space: a human element floating in a transparent network like a squadron in space.“[34] More meanings were imputed to the image than it had originally possessed. The long-term effort to create a projection space on which the starry sky could be observed may be considered the climax of a utopian project with origins going back to the pre-war period that was to be realised in the early 1920s.[35] Yet a contrary meaning may be ascribed to the small male figures connecting the network of triangular fields of a steel construction: instead of optimism disappointment and disillusionment with the future, instead of shared purpose loneliness. They find themselves on the edge of weightlessness, in danger of being swallowed up by the space surrounding the half-globe. The antimodernist modernists could see in their deployment across the iron dome a metaphor of the loneliness of the individual who is like an ant crawling on a construction resembling the world and trying to cover the cracks in his own mind, which has temporarily succumbed to the illusion of an attainable harmony.

The text first appeared in the book Years of Disarray 1908–1928. Avant-gardes in the Central Europe, edited by Karel Srp, published by Arbor vitae societas and Olomouc Museum of Art.

[1] Gustav Courbet, Dokumenty, Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění, Prague 1958, p. 156.

[2] The advertising leaflet was reprinted, among other books, in Karel Teige (ed.), Moderní soudobá architektura (MSA 1), Odeon, Prague 1929, p. 140.

[3] Karel Teige, Práce Jaromíra Krejcara, Nakladatelství Václava Petra, Prague 1933, p. 22.

[4] Milan Kundera, Velká utopie moderního básnictví, in: Guillaume Apollinaire, Alkoholy života, Československý spisovatel, Prague 1965, pp. 5–17.

[5] Milan Kundera, Slova, pojmy, situace (ed. Jitka Uhdeová), Atlantis, Brno 2014, p. 25.

[6] Ibid, p 26.

[7] Stanislav Kostka Neumann, Otevřená okna (1913), in Jiří Padrta, Osma a Skupina výtvarných umělců, Odeon, Prague 1992, p. 139.

[8] Ibid.

[9] In the flood of examples of various jobs, Neumann emphasised only some that seem a little dubious from today’s perspective. If Apollinaire in L’antitradition futuriste listed many jobs that the representatives of the avant-garde should avoid, Neumann by contrast named many others as models for contemporary artists, as they embodied the modern life: politicians, journalists, brokers, businessmen, engineers, designers. The avant-garde of the 1920s took as models only the two last jobs.

[10] Guillaume Apollinaire, Futuristická antitradice (Czech translation 1913), in:, O novém umění, Odeon, Prague 1974, p. 167.

[11] Stanislav Kostka Neumann, Otevřená okna (1913), in Jiří Padrta, Osma a Skupina výtvarných umělců, Odeon, Prague 1992, pp. 139–140.

[12] Karel Teige, Obrazy a předobrazy (1921), in: Avantgarda známá a neznámá (ed. Štěpán Vlašín), Svoboda, Prague 1971, p. 101–102.

[13] Milan Kundera, Slova, pojmy, situace (ed. Jitka Uhdeová), Atlantis, Brno 2014, p. 26.

[14] Ibid.

[15] František Langer, Byli a bylo, Československý spisovatel, Prague 1963, p. 160.

[16] Vladislav Vančura, Řád nové tvorby (1921), in Milan Blahynka and Štěpán Vlašín (eds). Řád nové tvorby, Nakladatelství Svoboda, Prague 1972, p. 54.

[17] Milan Kundera, Slova, pojmy, situace (ed. Jitka Uhdeová), Atlantis, Brno 2014, p. 25.

[18] In The Parrot on the Motorcycle Nezval writes about “continuous penetration“, which he understood more broadly than Kubišta: “Always a different mixture. The law of association, no other force than that which governs my thirst and my passions”. Closer to Kubišta was Vančura’s lecture On The So-Called New Art, published in January 1931 in Odeon’s Literary Courier, in which he connected world outlook and new artistic approaches with gravitation.

[19] Karel Teige, F. T. Marinetti a soudobý futurismus, in: ReD 2, February 1929, no. 6, p. 204.

[20] Ibid, p. 201.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Karel Teige, F. T. Marinetti a soudobý futurismus, in: ReD 2, February 1929, no. 6, p. 198.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Juliette Combes Latour, Félix Del Marle, Port, in Didier Ottinger (ed.),Le Futurisme a Paris, Centre Pompidou,

Paris, 2009, p. 180.

[26] Otakar Máčel, Kovový nábytek, in Jindřich Chatrný (ed.), Jindřich Halabala a Spojené uměleckoprůmyslové závody v Brně, Era, Brno 2003, pp. 84–94.

[27] Jindřich Halabala, Stroj a typ, Světozor 30, 1930, p. 606.

[28] Karel Teige, Technické podklady lyrismu, ReD 2, 1928–1929, no. 1, September 1928, p. 49.

[29] Moderní soudobá architektura (MSA 1), ed. Karel Teige, Odeon, Praha 1929, p. 34. The Marseilles transport bridge also featured in László Moholy-Nagy’s film Marseille vieux port of 1929.

[30] Vítězslav Nezval, Papoušek na motocyklu (1924), in Květoslav Chvatík and Zdeněk Pešat (eds.), Poetismus, Odeon, Praha 1967, p. 89.

[31] Milan Kundera, The Art of the Novel, Faber and Faber, London 1988, p. 126.

[32] Milan Kundera, Slova, pojmy, situace (ed. Jitka Uhdeová), Atlantis, Brno 2014, p. 39.

[33] Karel Teige (ed.), Moderní soudobá architektura (MSA 1), ed. Karel Teige, Odeon, Praha 1929, p. 95.

[34]László Moholy-Nagy, Von Material zu Architektur (1929), Florian Kupferberg, Mainz und Berlin 1968, p. 235.

[35] It is worth noting that the Prague planetarium, built as late as 1957–1960, was designed by one of the key architectural representatives of Devětsil, Jaroslav Fragner.

Imprint

| Author | Karel Srp (ed.) |

| Title | Years of Disarray '1908–1928. Avant-gardes in Central Europe |

| Publisher | Arbor vitae societas, Olomouc Museum of Art |

| Published | 2018 |

| Index | Karel Srp Olomouc Museum of Art |