Joanna Warsza: Flaka, you grew up in Kosovo, you were a refugee as a child during the Yugoslav Wars, and you have lived in Germany for over a decade. It struck me what you once said: “The moment I call a place home…it alarms me that time has come to leave.” Can you speak about the ideas of belonging and non-belonging in your life and work?

Flaka Haliti: To me home comes as a double-edged sword. It holds a sentimental tone of what has become familiar to us with time and is growing in meaning in a context of place. It also offers a recognition value, a kind of comfort, a safe place of belonging, which we humans (stupidly or not) constantly strive for. Nothing wrong with it unless that type of belonging becomes an absolute commodity, and daily life turns into an end-loop. It grows static, and leaves no space for the necessary and productive unrehearsed encounters.

The desire for home and belonging should not be fixed in an absolut singularity, but could be something that moves between categories and places. Something which is constituted in relation to the other, and is able to set into motion different possibilities. Something that creates a kind of potentiality, that manifests as a place of in-betweenness, or a process of becoming. A state similar to what queer identity strives for. As something that is „not yet conscious”. I believe home should be understood in that gap.

Today, in Munich, one of your homes, you cultivate an in-between status of expat and immigrant at the same time, how do you navigate between these logics?

I think it is hard to be an international or expat in the West as someone who comes from a non-Western country – as in my case. Due to geopolitical reasons of how Kosovo is perceived in the West (often unprivileged, economically disadvantaged), I’m automatically perceived as an immigrant, even if I am there as an art professional. Expertise is one of the first characteristics of being an expat. In 2012 I made the work called Expatium, trying to analyse the integration of the expat community in Frankfurt. I was intrigued by the meaning of the word expat/expatium, which comes from the mid-16th century and means ‘to roam freely’, from the Latin exspatiari ‘move beyond one’s usual bounds’; ex- ‘out, from’ and spatiari ‘to walk’ from spatium: ‘space’. International expats often act in a similar way as immigrants –– but are not criticised for it when it comes to integration. Both groups create a segregated parallel reality in Frankfurt. But when it comes to the question of integration or assimilation, for expats it is a choice, while for immigrants it is still a must.

How do you question those given rights of representation?

As long as your status is defined either as an immigrant or as an expat, you are visible, therefore you can be represented and you have rights to exist as a political entity, meaning you theoretically have a political voice (most expats don’t care). The better (often higher by class or race) you are defined – the better integration and benefits you might receive socially. I believe those conditions of belonging and representation should be queered. For me being neither an expat nor an immigrant but a combination of both is forging a political entity that I would like to promote and stand for. I have been stressing this position of agency within in-betweenness for 10 years, and more recently in the new series called WHOSE BONES.

Last autumn in Prishtina we were talking in front of your sculpture Under the Sun –– Explain What Happened, 2022 made from the left-over windows burnt by the sun in the NATO hangars located across Kosovo after the Yugoslav Wars. Your sculpture is made out of scrap material, but its provenance is hard to detect, since it looks abstract and elegant. Back then you said that in your work, derelict material must stop looking as such, that they need a life-after-life of their own. What is your approach to materials and materiality?

I consider it problematic if the discarded object in the artwork still screams “I am an old and used-discarded object” … I think that should be avoided. In order to give the object an afterlife in the artwork one needs to find out what historical spectre haunts that discarded item. Avary Gordon writes in her book Ghostly Matters that everything is haunted by the spectre of something. Everything has another potentiality hidden behind. While Muñoz describes potentiality as “a certain mode of non-being that is eminent, it is present but actually does not exist in the present tense.”

Furthermore to transgress its rules, one needs to subvert the original meaning of an object, and begin to form or create its own counter order. From here a space of trans-temporal narrative is created and the perception of the discarded object changes by putting it in relation with a new spatial context.

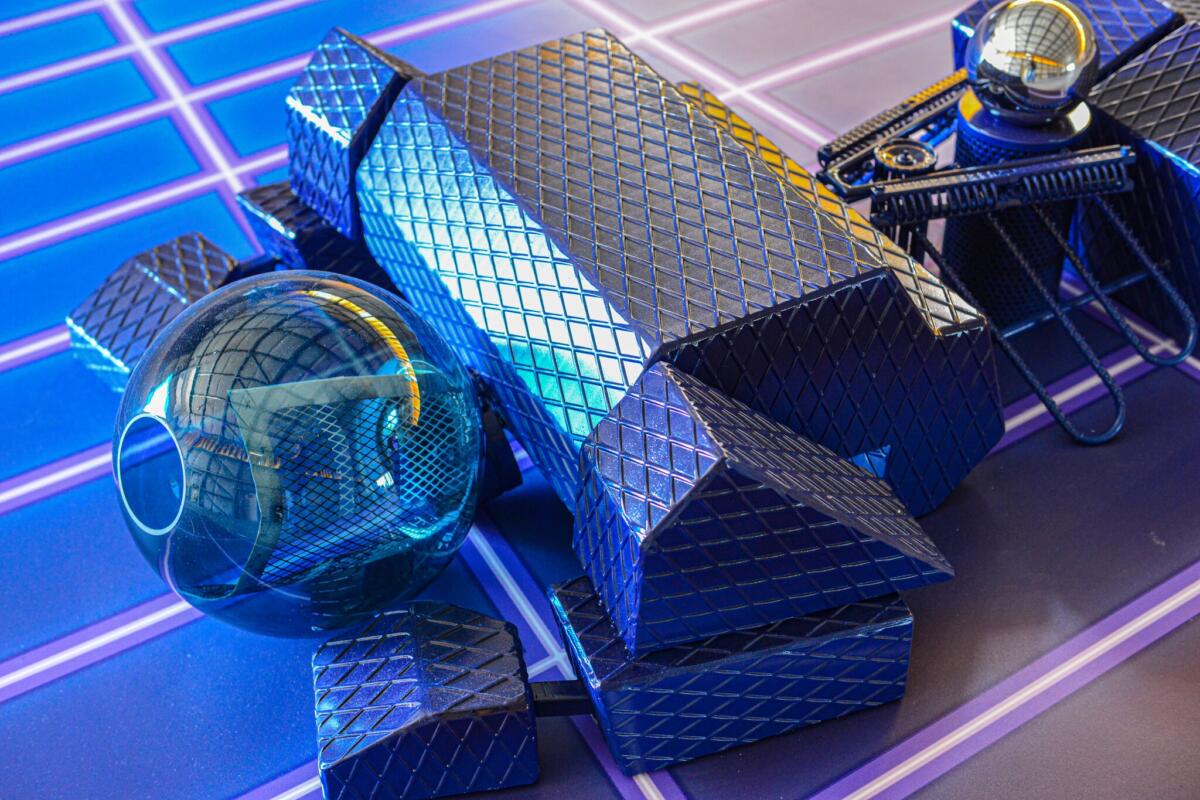

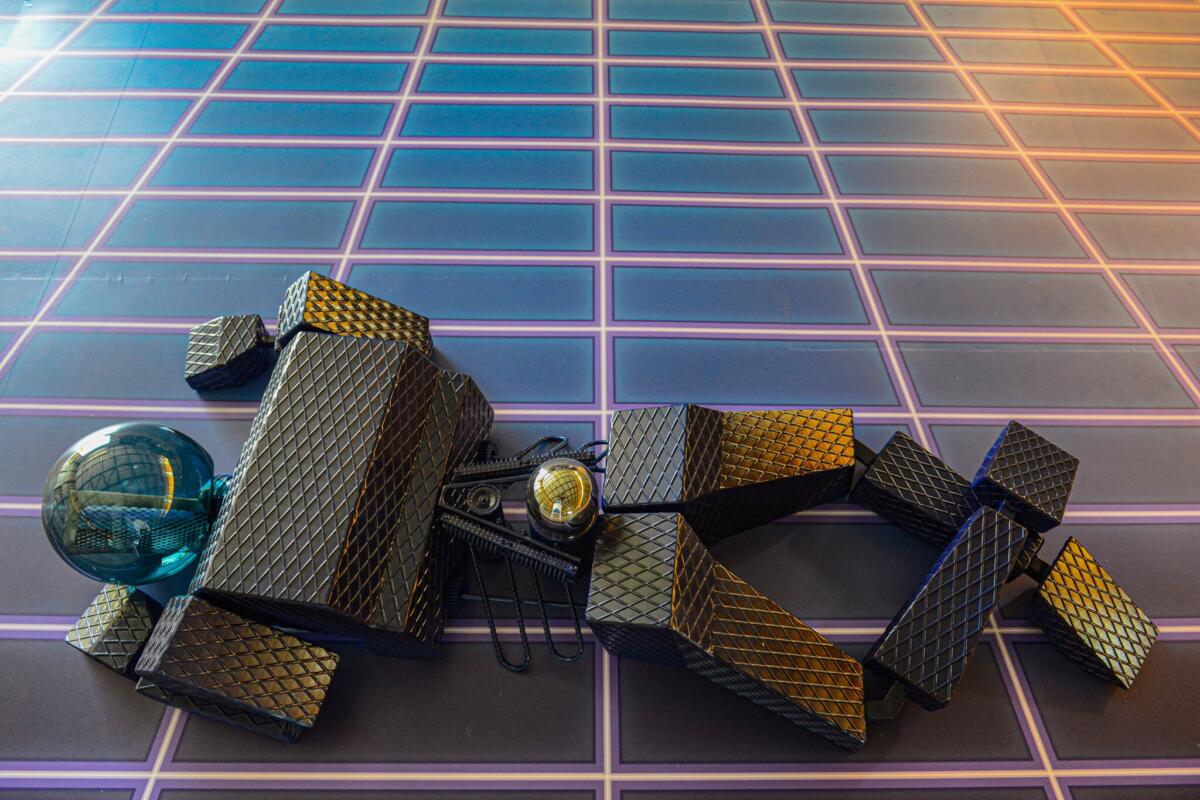

It is the strategy I have also implemented with the series of robots (2017-2021) called, Its Urgency Got Lost in Reverse (While Being in Constant Delay), which have also been fabricated from NATO leftovers from military camps in Kosovo.

For the 3. Autostrada Biennale in 2021 we were working with your robots. They are lazy robots, and a lazy robot ontologically contradicts its basic function, being a productive addition to the life of humans, a mechanical extension of efficiency, a servant of sorts. The protagonists of Its Urgency Got Lost in Reverse (While Being in Constant Delay) are four unproductive beings. Tell us more about them, how did they land in your life? Why did they come in chapters over time?

Good to bring the laziness of the robot as an entry point. There are four robot installations created in this series. They perform the status quo and a feeling of being stuck. The unproductive narrative slightly changes when one knows that I produced them backwards, against chronology. Their passive pose is only perceived more actively if you’re looking at them in reverse; they were produced between 2021 and 2017 from past tense 2021 to present tense 2017. Like sometimes in the movies, when we get to know that the first scene was in fact the last one. And that shifts the entire logic of the plot.

The four robots are made from the objects stemming from KFOR bases. They are sitting or laying down in a suspended plot. They perform a gesture of demilitarisation through an aesthetic act that resembles and assembles the discarded building blocks of a peace process. Within each installation a particular process of “laziness” emerges in which the interval completes its own cycle of referring to the status quo in relation to critical questions about the transnational versus national politics of representation in Kosovo.

And the title?

The delirious title – Its Urgency Got Lost in Reverse (while Being in Constant Delay) – as helpless as it sounds, it carries actions, movement, and is upbeat…it is not about the end result, but about the potentiality of the act of “going” back and forth. Sometimes repeating or reversing an action can produce more than just a constant linearity.

What is the relation of those robots to time?

The robots might manifest feelings of reversal, delay, and a loss of their own urgency. They also ask what if history was lived in reverse? Would a nightmare of being haunted and stuck in Kosovo, in a constant delay in relation to the West and NATO be questioned? Can they act in their own space as trans-historic devices? Is the ‘mission completed’? They leave the questions unanswered.

Moreover, the four robots capture the intervals that take place slowly over time by going backward. Making time frame by frame, I wanted this reversal to be another promise of futurity, something that is not quite here but again in the process of becoming.

Robots made from NATO leftovers, coming back as artworks exhibited in a former NATO hangar become trans-temporal narratives. They become bodies where the past, present and future blur in an amalgam of temporalities, a metaphor for time.

I am wondering about the logic of the language of your titles, being forcefully poetic. Which kind of relation to the language emanates from them?

I am inspired by Glissant’s notion of the counterpoetic, when he is referring to language as resistance.“ Anti-poetic”, “forced poetics”, “constrained poetics”, according to Glissant, are the practices of language which become impossible to understand, when it becomes an ambiguous kind of verbal performance, “routine verbal delirium…” “…poetics and the unconsciousness”. When I apply this to my titles, they let the works become «œuvre ouverte», with multiple entry points for reading the artworks, resisting to be grasped completely. They keep the right to be misunderstood and opaque.

I deliberately often write the titles grammatically wrong. As a basis of an antagonistic or subversive relationship to the language which I nevertheless have to use. Not as an impulse which is always present but as an expression which is never achieved. “Forced poetics” for Glissant is also when harmonies of language become impossible to understand – like for example the title, Its Urgency Got Lost in Reverse (While Being in Constant Delay). It works and it doesn’t work at the same time. It forces itself to find a way around. Like a detour does, while desperately trying to follow the syntax, yet mocking it. Detours are manoeuvre strategies of survival. The titles are also like a chicken-egg situation. One doesn’t know if the title makes the artwork or if the artwork brought the title. What came first?

One of the other terms of the Flaka glossary is that of cruel optimism. What does it mean to you and do you relate it to your native Kosovo?

First time I came across Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism I read it in the context of the postwar development of Kosovo, the transition and the practical impossibility of building a newly born state through the supervision of western powers such as the EU, UN and NATO, etc. Berlant writes that “optimism is cruel when the object/scene that ignites a sense of possibility actually makes it impossible to attain the expansive transformation. Optimism might not feel optimistic. Because optimism is ambitious, at any moment it might feel like anything, including nothing”. In this line the dispositions of associations like the UN, EU and NATO often are brought into negotiations with an impossibility to define what is considered a failure and a success in this “democratisation” process of state building, like Kosovo after the war. Or perhaps the contradiction of the word “democracy” falls also in the logic of cruel optimism. Cruel optimism can be read as well in the same light when we try to grasp the absurdity of ‘Western-inspired Imitation Imperative’ as Krastev and Holmes defined it, speaking about the ex-communist countries. Their task to become Europeanized simply meant modernisation by imitation and integration by assimilation. My response to this was a work I did in 2020, I’m imitating you, but you are changing all the time.

And what are you working on now?

I’m preparing the next suspended plot for an upcoming solo show in Cukrarna in Ljubljana, titled as a riddle: I Shout, Your Echo Bounce, What Am I?. I know you think `bounce’ should be written as ‘bounces’, but remember what I told you about forced poetics. Writing a title purposefully wrong. A bit like a Mannerist artist in the 14th/15th century would say, by doing things wrong you know how to make things right. It is my favourite period in art, since in the context of art history it is the most ambiguous one and the most misunderstood. But think about it, art history as a discourse was born at that time. So misunderstandings keep me going.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Flaka Haliti is an artist from Prishtina, who lives in Munich, she recently presented her work at the 3. Autostrada Biennale, Manifesta 14 in Prishtina and Cukrarna in Lubljana.

Joanna Warsza is a curator, editor and writer, currently the co-curator of the 4. Autostrada Biennale in Kosovo, opening July 7.

Imprint

| Artist | Flaka Haliti |

| Website | autostradabiennale.org |

| Index | Autostrada Biennale in Kosovo Cukrarna Flaka Haliti Joanna Warsza Manifesta 14 |