1.

“Just a few years ago, I wouldn’t have painted a picture like this. I’d have been convinced that it was terribly grandiloquent,” Martina Smutná says as she pulls one of her latest canvases out from a stack stored in her studio. In the painting, a mother is striding briskly somewhere with a child slung on her back and a plastic carrier bag in one hand. It is a genre scene of the kind we observe in great numbers every day, even though this one is actually being played out against a landscape of post-apocalyptic appearance. All that stretches out around the central characters, whose complexions are the rosy red of prawns thrown into boiling water, is arid, dark brown soil devoid of even a single blade of grass. In the second painting of the same series, two teenagers are sitting in the midst of an identical, barren landscape, their gazes fixed on the screens of their smartphones. A final scene completes the triptych. Three figures are seated at a table laid with a check cloth. The table is completely empty, yet the central characters are twisting cutlery in their hands as if they were striving either to recall how to handle it or to perform a mime of suppertime. Although the head of one of the figures is adorned with a silver-haired wig in the fashion of the eighteenth century, evoking associations with a Rococo fête galante, the situation is rather more reminiscent of a wake.

Smutná’s triptych is a reaction to the spectre of the rapidly accelerating climate crisis, but with no descent into the typical extremes of helpless apathy and cultural catastrophism or naïve, proselytical activism. She seems to be in no doubt as to the fact that, when it comes to the fight against that crisis, artists have more or less the same agency at their disposal as philatelists and sellers of used Volkswagens. As with the mother in her painting, all that remains is to do your bit, which, in this case, means… telling a story. Sometimes, though, the most difficult thing of all is precisely that; telling a simple story.

Smutná’s triptych is a reaction to the spectre of the rapidly accelerating climate crisis, but with no descent into the typical extremes of helpless apathy and cultural catastrophism or naïve, proselytical activism.

2.

Painters are undoubtedly in the vanguard of artists who are fixated on their medium and Czech painters give every appearance of occupying a particular place within that group. The fields of interest in contemporary Czech painting are highlighted by a cross-sectional exhibition being held just over an hour away from Prague, in the small town of Humpolec, where the 8smička Art Zone opened in 2018 in a former textile factory. Curated by Dušan Brozman and Emma Hanzlíková in that newly established venue, Retina: Possibilities of Painting (1989-2019) is an exhibition of considerable panache, with the ambition of sketching a synthetic picture of painting in the Czech Republic from the collapse of the Iron Curtain to today. Although the title makes reference to the category contemptuously dubbed by Duchamp as ‘retinal’, the works on display in Humpolec just as often accord with another Duchampian categorisation, “art (…) in the service of the mind”[1] as they do with ‘retinal art’. A prominent place in the story spun by Brozman and Hanzlíková is held by the struggle with the very matter and flatness of a painting and with the history of abstraction. Black square mutations alone have received their own, really quite extensive nook. Further chapters of the fairly masculinised history of modern Czech painting told by the curators are thus marked by canvases by Milan Houser and Milan Grygar, fractured by brown-and-grey, texture-dense figuration in the style of Daniel Pitín, mentally still slightly stuck in the nineteen eighties, but the eighties as stamped by caustic postmodernism rather than by the ironically joyous transavantgarde. Set against the backdrop of the Czechoslovakian neo-avant-garde, Czech painters often prove to be exceptionally miserable.

Martina Smutná, House n. 1817, from the series Et in Arcadia Ego, courtesy of the artist

Echoes of both the one and the other, of both autotelic abstraction and old-school postmodernism, are present in Martina Smutná’s early works dating from her student years. In her Et in Arcadia Ego series, she sets houses from Czech suburbs and small towns against backgrounds of conventional, classic landscapes which seem to quote from canvases by Lorrain. She immerses the homes in a luscious greenery born of academic dreams. A contrast with this is set up by the tight, photographically framed compositions, which are shaped by a modernist sensitivity towards detail and the texture of materials. All of this is bathed in a Czech version of joyful, vernacular postmodernism, which comes across as fairly muted against the backcloth of its Polish and Slovakian neighbours. Smutná took Et in Arcadia Ego further in a slightly later series, Die Klasizistischen Strukturen, where she presented the typology of architectural components which feature in the houses of small towns and are derived from classical architecture.

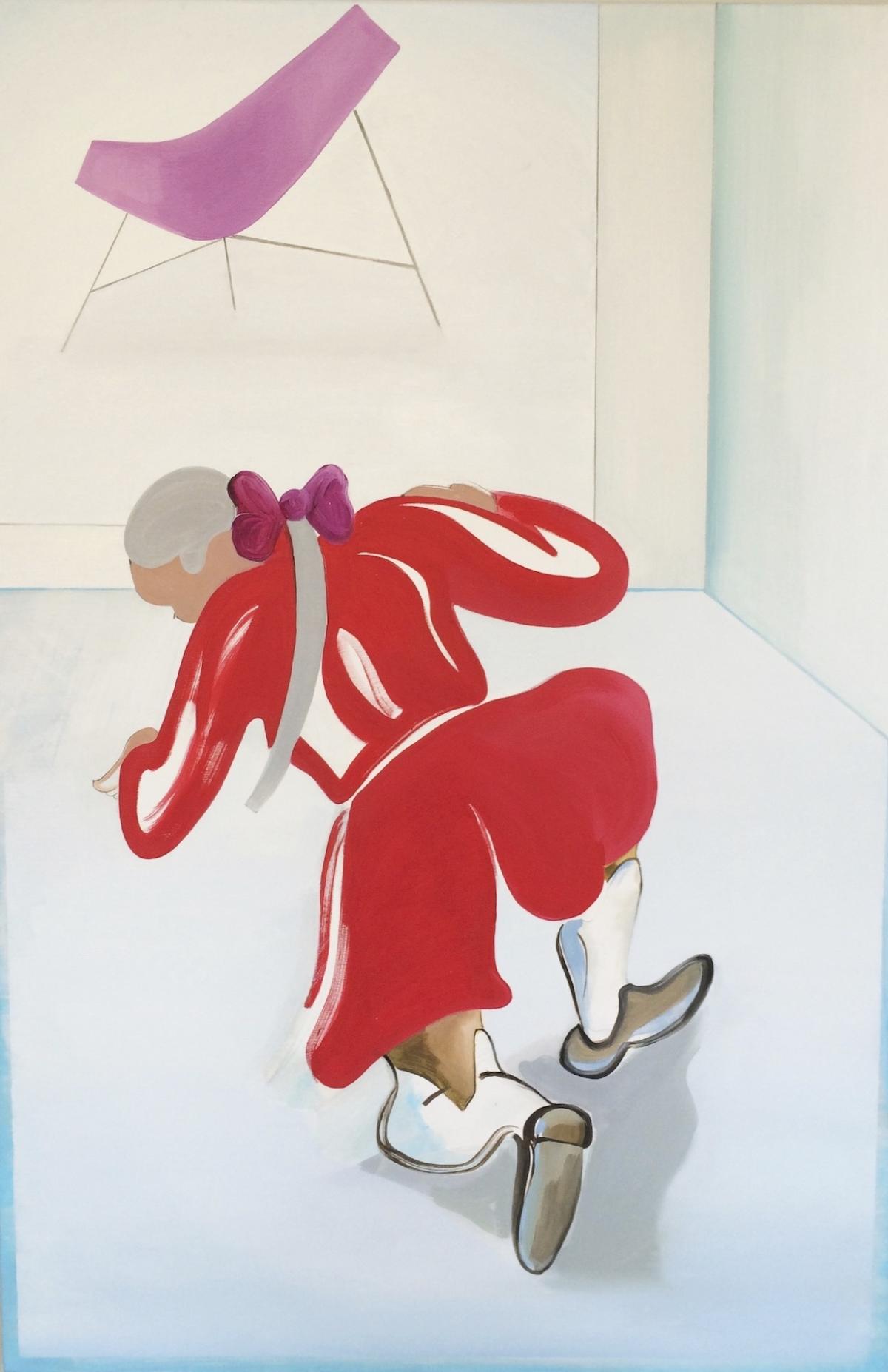

However, it was not long before she began to move away from her canvas stretchers and started creating spatial structures. In her Stronger Dog Fucks (2015), the canvases escape from the walls and become part of metal structures which have their origins in a children’s playground. Dangling, slung on sculptural stands, they co-create dysfunctional slides and climbing frames. The representations themselves are now nothing like her earlier works. They have become flatter, colourful and somewhat illustrative, akin to the art of Ella Kruglyanskaya and Sanya Kantarovsky.

3.

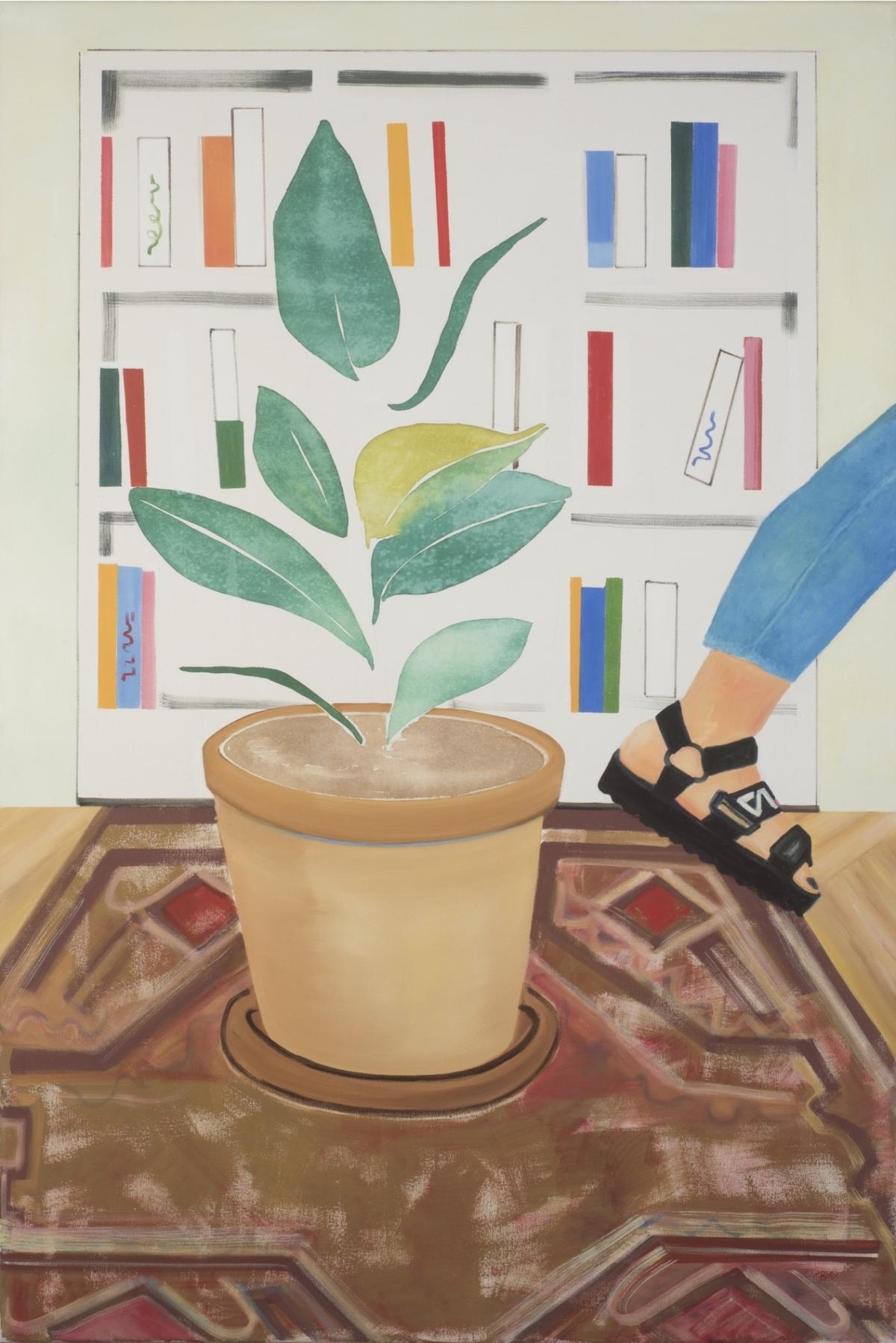

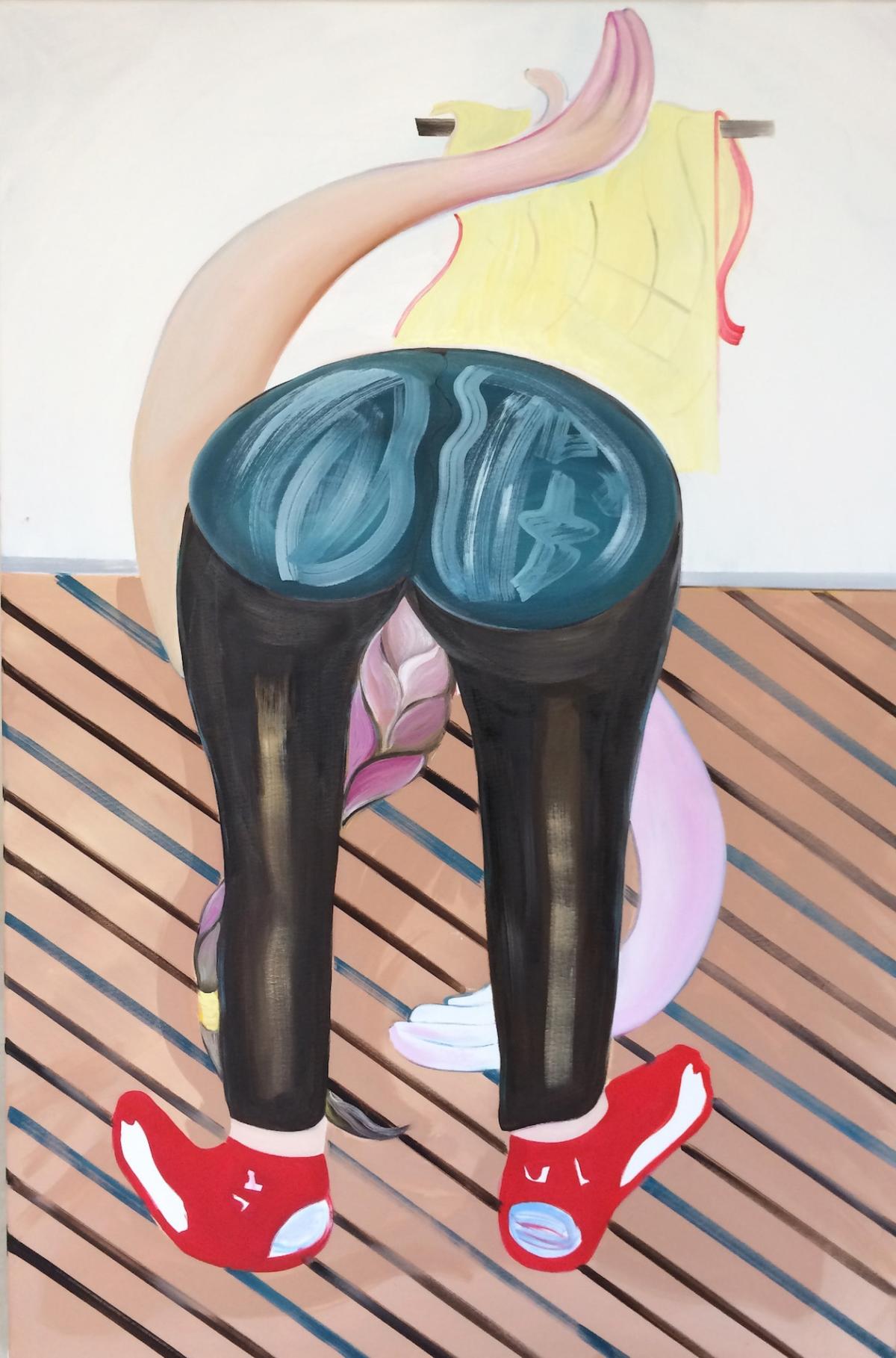

The critical dimension of Smutná’s work would only emerge at the moment when, instead of contemplating the competitive drive which characterises structures for children more or less from the cradle, she turns her attention to her own surroundings. When she brings yoga and the minuet together in one series, she is pointing to the disciplining nature of middle-class entertainments without censuring them ex cathedra. When she studies obsessions with healthy foods straight from the most ethical production cooperatives under the sun and when she paints a photo from a friend’s Instagram page, where what emerges from an apparently laid-back composition is a carefully arranged constellation of well-filled bookshelves, a rubber plant, a Persian rug and a Fila sandal, she is not commenting on environmental responsibility and a fondness for nice interiors, but revealing the class-based underpinnings of both. In this way, she avails herself of the aesthetic potential of painting itself without avoiding the fact that this is the medium which makes it easiest to commercialise or refine an aspect of a domestic interior. Rather than the ‘white cube’ of an art gallery, the natural environment for Smutná’s art seems more to be an aestheticised domestic interior of the kind found in photo shoots for “Kinfolk” magazine, for instance. The slender lines, saturated colours and luminous planes, beneath which fragments of white canvas shine through, are thus meant to be liked, to allure. In the end, as Peter Doig has said, we look at a painting like we look at a lover’s face. In Martina Smutná painting, aestheticising becomes not an enemy, but a tool for critical analysis.

Smutná avails herself of the aesthetic potential of painting itself without avoiding the fact that this is the medium which makes it easiest to commercialise or refine an aspect of a domestic interior.

The turning point along the road to developing that critical instrument was her work for her Loss series, where her paintings began to migrate from her spatial structures and return to the walls. Semi-abstract, figured, sometimes tightened on a stretcher, sometimes slung from metal towel rails of the kind found in domestic kitchens, at first glance they do nothing to betray any critical ambition. Loss is an ironic bastard born of formalist abstraction and ordinary kitchen towels with flowery, abstract patterns. The simple, decorative forms contain a chunk of art history. It is not difficult to discern after-images of Matisse and Daniel Buren in them or to perceive their affinity with contemporary women painters, with the simple, semi-abstract objects in Alice Nikitinova’s paintings and the flat still lifes of Holly Coulis. As we plunge into a web traced out with formal references, we allow ourselves to be drawn into the painter’s game, for Loss is also largely a parody of the revival of modernist corpses within the Zombie Formalism which is making itself so exceptionally at home in the Czech Republic at present. However, Smutná, juggler of historical references, tugs serious reflections on the essence of painting down from their pedestal and transfers them to a humdrum context. In Gertrude Stein’s eyes, Cubism overtook reality and moulded the way in which she viewed a landscape through an aeroplane window long after she had seen Picasso’s Cubist paintings, for instance. Nowadays, even a tea towel made in China for a couple of yen looks less than innocent.

Amidst the paintings-cum-towels, though, we come across a representation which, to all appearances, is completely at odds with all the other works. A transposition of one of Chardin’s washerwomen, this single, simple, figurative composition shifts the entire viewpoint somewhat and bestows a different eloquence on the other paintings. They are no longer straightforward decorative objects, but tools of work. Reproductive and unseen work geared not towards the production of goods, but to maintaining the established order.

4.

The theme of work performed by women returns in Smutná’s Together We’ll Mow, Thresh and Deliver the Harvest series, where she transforms the kind of images of women workers which were typical of social realist propaganda. As she conceives them, the women tractor drivers and steel workers have none of social realism’s hardness or its sharply hewn, solid figures with their typical squatness. These central characters are nothing like its ardent-faced, muscular-armed women. They are rather more ethereal, like models on magazine covers. Much the same may be said of their tools, their hammers and rakes, which look more like designer accessories. Smutná’s women workers draw as much on social realism as on the parodies of it implicit in Malevich’s post-Suprematist peasants from the turn of the nineteen twenties and thirties. They even have almost identically smooth, featureless, black-and-white heads.

In the fusion of these conventions and Smutná’s characteristic, illustrative charm, the women workers become the heroines of an idealised fable about emancipation. They demonstrate that the world which existed in the social realist propaganda does not belong to the past, for it is a world which never came to pass. The visual culture of social realism may have portrayed women workers standing shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts, but, in reality, they were still condemned to working in the lowliest and most poorly-paid of factory jobs. Like Malevich’s post-Suprematist peasants, male and female alike, Smutná’s women workers are universal, moving beyond corporeality, ethereal as the saints in Byzantine icons. On the stratum of gender, they also embody the unattained ideal of the new, androgynous, socialist human being.

Smutná is about as far away as you can get from emphasising expression and fixation on the body. Her paintings are sensual in a pop-art way, like Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nudes series, ideal more as a product than a sexualised body.

However, Smutná focuses not on the body, but on gesture, on work. This conception encompasses a statement, an answer to a question which preys on her mind. What kind of painting can be called feminist? The largest and most important exhibition of feminist painting in Poland in recent years was Paint, also known as Blood, held at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in the summer of 2019. The curator, Natalia Sielewicz, proved that painting, through both the material sensuality of the medium and the performative nature of the very act itself, has a natural inclination to operate within the affective register and it was, indeed, in the field demarcated by the body and affect that she sought present-day manifestations of feminist painting. Smutná is about as far away as you can get from emphasising expression and fixation on the body. Her paintings are sensual in a pop-art way, like Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nudes series, ideal more as a product than a sexualised body.

Paradoxically, the road Smutná has trodden is similar to that taken by the derided Zombie Formalists, travelling via formal and spatial experiments reflecting on the materiality of the painting itself and the consequences of that materiality. However, there is one fundamental difference to her path. Instead of grinding to a halt at the stage of scholastic solutions in a painterly ivory tower, Smutná adds specific class, social and historical references. At the same time, she proves that, rather than affective disgorging, feminist painting can take the form of an unassuming tea towel on a kitchen hook.

English translation: Caryl Swift

This article was written and published in the frame of East Art Mags programme with the support of the International Visegrad Fund.

[1] Marcel Duchamp, as quoted in H. H. Arnason and Marla F. Prather, History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography (Fourth Edition) (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998), p. 274, retrieved from https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/marcel-duchamp-and-the-readymade/ on 15.12.2019.