Agnieszka Jankowska-Marzec: Conversations with artists often begin with the question about origins of their fascination with art, and I’d also like to know why have you taken a serious interest in painting?

Mateusz Sarzyński: Like most children, I was eager to draw, but I received no encouragement from my family to pursue an education in this area. In my home environment (I come from a small town in eastern Poland), being an artist is not exactly considered a serious occupation. So I didn’t go to a secondary school for fine arts, and when it came to choosing a university degree, studying architecture seemed a reliable option. There I could employ, my family believed, my drawing skills in a practical way.

And although you did graduate from the Faculty of Architecture of the Cracow University of Technology, you did not become a practicing architect.

While studying, I discovered I was rather more attracted to classes in painting and drawing, belonging to our curriculum. Particularly, I appreciated conversations with and corrections form Marek Firek (a member of the now disbanded Ładnie Group), who was then employed at the University. At home, I arranged still lifes, and painted and drew them for my own satisfaction. And while working on my university projects, I began to realize that their manner of visual presentation was becoming, in my experience, their most essential aspect. As part of my diploma, I painted a perspective view in oil, which was quite unheard-of. My professors concluded that “the boy can paint, but like a painter, not an architect.” And even though my diploma, a design for a contemporary art museum, completed under the supervision of Prof. Dariusz Kozłowski, was highly regarded (e.g. I got an award in the 15th edition of the “Concrete Architecture” [“Architektura Betonowa”] competition and the Krakow Branch Association of Polish Architects [SARP] award for the best diploma of the year), I’d realised I didn’t want to pursue a career in architecture.

You, nevertheless, stress the fact that the time you spent studying architecture wasn’t wasted.

Architecture has given me a working discipline and, most importantly, has led me to believe that the concept and the question of what purpose a particular piece (a building, an object, a painting) is supposed to serve are essential to any creative activity. Colloquially speaking, if I design a loo, no matter how impressive, but it will be impossible to use it comfortably, the thing ceases to be a loo and becomes a sculpture. Obviously, in painting, the value of practical utility doesn’t quite figure, but just as in designing, there are principles and rules, with which I grapple. First, I try to picture an image in my head (in architecture, it’s a structure, its proportions etc.) and instead of roaming the corridors of the building I’d design, I travel the ‘path’ from A to B, while painting the image in my brain. When I’m already standing in front of the canvas, I sometimes deviate from my previous design, but I always approach painting as a kind a logical puzzle, a brain-teaser, which resembles playing chess that I also enjoy. The fact that I paint quickly, often one painting a day, doesn’t mean that I produce them solely on the basis of emotions, without a pre-considered ‘draft’.

You are fascinated by brutalist architecture, and Louis Kahn is among your favourite architects.

I was attracted not by the rawness of brutalist architecture, but by its honesty. A wall is a wall, no attempt is made to mask any of its elements, and probably the same applies to my painting. I don’t conceal my mistakes, the paint runs down the canvas, because it is paint, the lines are crooked, because I don’t use a ruler, optical devices or a projector: that’s the stylistics that suits me. Louis Kahn seems to have been a nice guy, an outstanding architect and a skilful artist. I really liked it, when I found out he personally assisted the construction of the parliament in Dhaka, including teaching ordinary workers how to make a bamboo scaffolding. He was very charismatic, and I don’t seem to like insipid people.

Architecture has given me a working discipline and, most importantly, has led me to believe that the concept and the question of what purpose a particular piece is supposed to serve are essential to any creative activity.

The choice of your second degree was no longer dictated by practical reasons, but a desire to develop your interest in painting. Still, you decided to study at the Faculty of Graphic Arts of the Krakow Academy of Fine Art.

Yes, I chose graphics, rather than painting, because I came across the work of Prof. Dariusz Vasina. I wanted to be connected to professors whose artistic activity appeals to me. I enjoy studying under his supervision, because as he says, he tries not to disturb his students, and whenever they need it, he talks to them and discuss their work as partners. It was also not insignificant that, being their student, I could use a studio in the city centre, which otherwise I couldn’t afford.

We won’t be able to avoid the question about artists whose work inspire you. I recall you once mentioning Christian Jankowski and Chris Burden.

Indeed, a video recording of Christian Jankowski’s 1992 performance, The Hunt, was one of the first ‘manifestations’ of contemporary art I encountered. The concept of showing a man hunting groceries with a bow and arrow at an Aldi market seemed to me, on the one hand, ridiculous, and on the other, incredibly witty. He demonstrated there absurdities of contemporary consumerist culture both in an unpretentious way and, at the same time, in a broader historical perspective. In turn, Chris Burden’s performance, during which the artist is shot with live ammunition in the name of art, set a limit I would always be afraid to cross. Both artists, however, have strengthened my belief in the importance of the conceptual dimension of a work, and that humour or irony are indispensable in art.

Looking at your paintings, it is no surprise that you feel closest to painters whose work could be subsumed under a broadly understood category of expressionism.

Indeed, I value the work of Eugéne Delacroix, Henry Tylor, Daniel Richter, William L. Hawking and Rose Wylie, not only because of their high artistic quality, but also because I feel a kinship with them – at a ‘human’ level as well: some of their life experiences provoke my sympathy, or even compassion. I have Polish favs, too: Artur Nacht-Samborski and Andrzej Wróblewski. I mention these artists, because I’ve recently been painting many paintings that are pastiches in character, often free travesties of works by the old masters, as I still have the feeling that I can learn a lot from them.

So you will probably agree with Adrian Ghenie’s claim that chronology in art does not exist, since Caravaggio and de Kooning, in fact, tried to solve similar problems of painting. They worked through them on canvas, whereas you also ‘paint’ on human skin, working as a tattoo artist.

Yes, I try to treat tattooing in the same way I approach painting. The form is different, as it’s a completely different medium, but the thinking is similar. It seems to me that tattooing requires a little more self-confidence. An image on canvas can be destroyed or repainted. It is, of course, also possible to remove a tattoo from a human, but it is quite painful and time-consuming. I sometimes encountered instance of art engaged in various issues. I have often seen slogans written on canvas or films presenting some problem. I decided to go a little further. I have not yet found a more powerful form of expression than injecting ink under the skin. Besides, I like drawings and started collecting them on my own skin. So far the collection is not too large, but I collect tattoos from people whose work I appreciate. I met many interesting people and great artists in the tattoo shop. Who knows if they are not the true successors to Caravaggio?

I try to treat tattooing in the same way I approach painting. The form is different, as it’s a completely different medium, but the thinking is similar.

Your painting first appeared on the Internet. How important is your online presence?

I have been showing my things online for a year and a half, or so. This is not a long time. I only have an Instagram account, because someone once told me it was a cool medium, and that many people use it to ‘showcase’ their activities. I’m still very sceptical about it, but in this time, I discovered many interesting artists and took part in a few exhibitions, which wouldn’t have happened if not for Instagram. A huge advantage and, at the same time, a huge danger lies in the fact that, at any moment, you can share your current work with a great number of people, without geographical limitations. Of course, much depends on the user’s reach, but I can easily imagine a situation where a person reaches several thousand people within a few hours. On one hand, it’s cool, on the other, it is a kind of a burden. In addition, every day, I see hundreds of new pieces being produced in various corners of the world. That’s motivating, but it also makes you ask yourself the question: what is the point of painting another picture if there are already millions of them on the internet? Why should I strive to be an artist if there are already so many others, the world of art is hermetic and there’s not much space in it?

Where do you situate yourself on the map of young Polish contemporary art? Do you feel a generational affinity, an artistic kinship with artists born in the ‘90s? Or, perhaps, you consider such use of a generational criterion, as a handy tool for defining your work, to be misguided.

I don’t know what the generation of people born in the 90’s is like, I don’t have a sufficient distance to know it. I sometimes read something about young Polish artists on-line, but I don’t feel that my connection with them is stronger than with people born in other periods. I paint pictures, and painting, in my opinion, has changed very little since the Paleolithic. I’m not an intermedia artist, I play the game in which I always stick to the same rules. There’s a surface on which colourful daubs appears, and all the others watch it. Also, an idea, a concept, a message is significant. I’m not sure if embroiling a generation in it makes anything easier. Besides, we’ve previously agreed with Adrian Ghenie’s claim that chronology in art does not exist, so what’s the reason in making up artificial criteria? In any case, it constructs a weird situation, we – born in a given decade – versus all the others. As for artists themselves, my peers, I like the work of some more than the work of others, but the same goes for those born in other times.

What are you currently working on?

I have plenty of plans, but at the moment I focus only on the nearest future, or the period before my trip to New York (my artistic residence there is scheduled for November). All the time, I’m tattooing and painting. I still have more ideas for new pics and drawings than time to produce them. In October, I’ll be taking part in a group exhibition in North Yorkshire (Three works, Scarborough, England). Besides, there are a few things I am really looking forward to, but I’d rather not brag about them, lest they don’t come to be.

Imprint

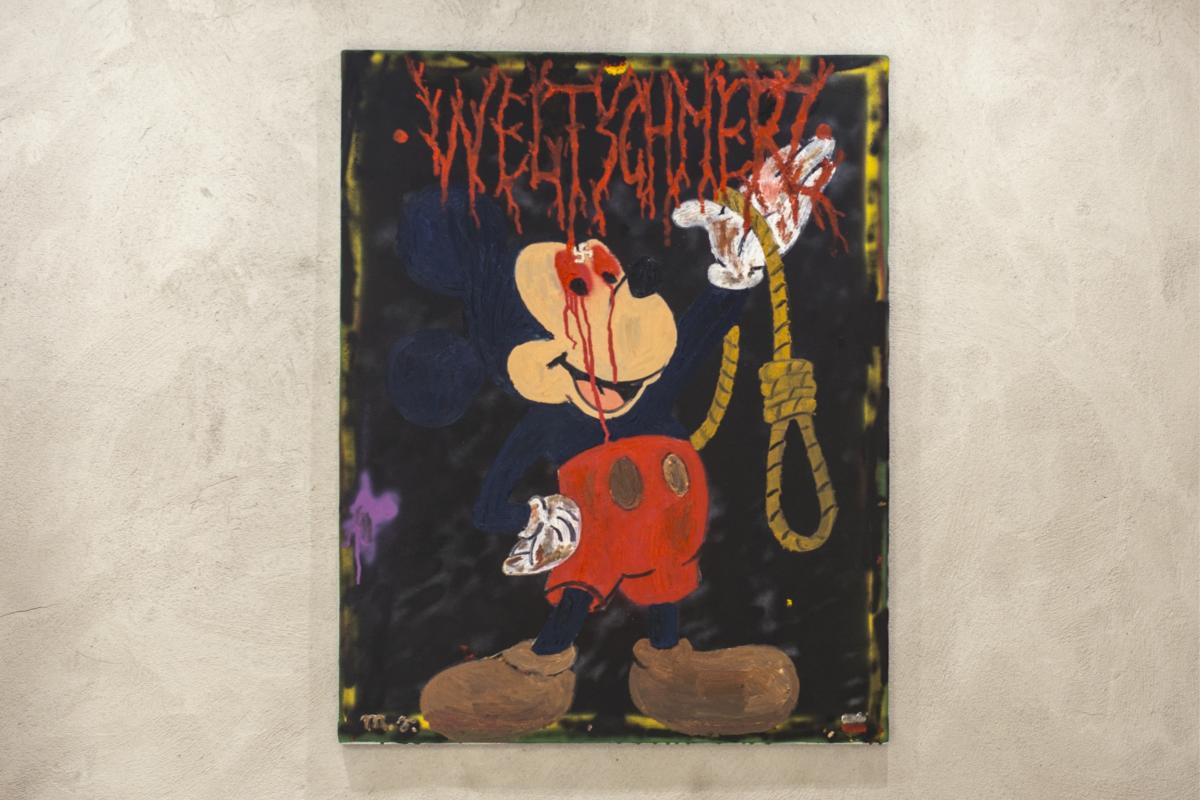

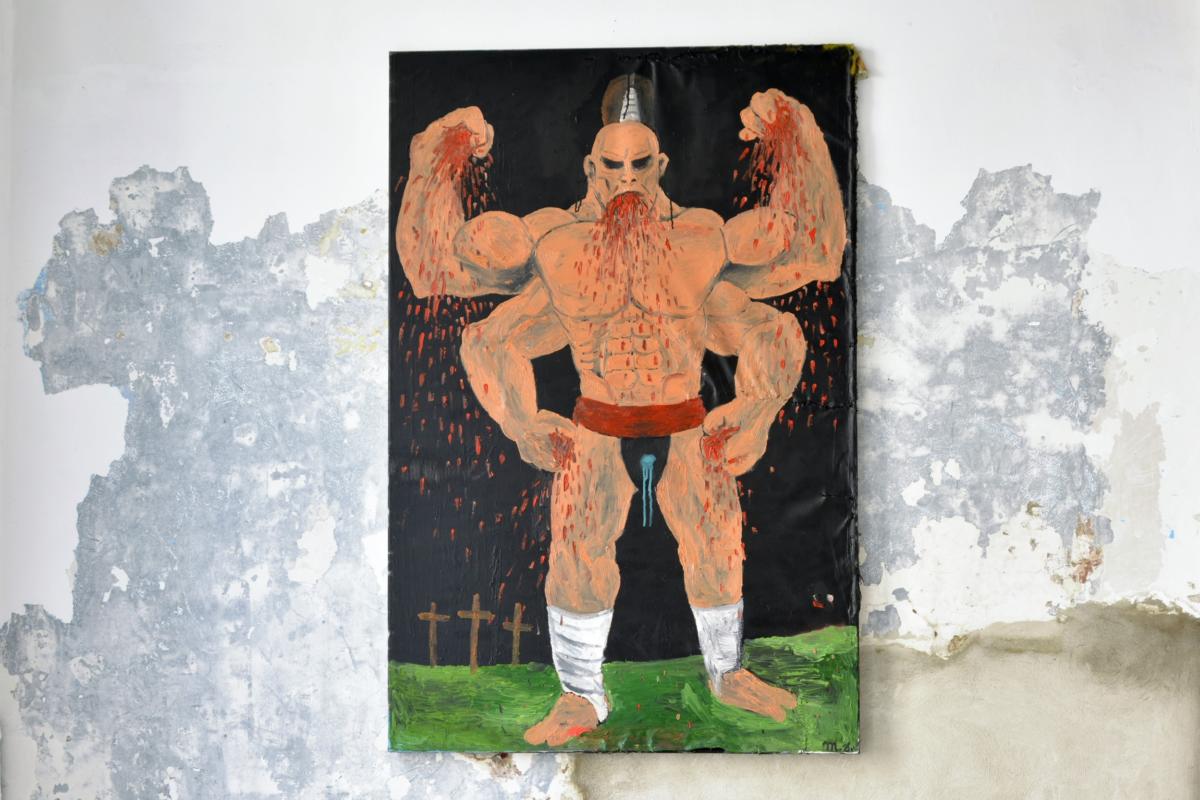

| Artist | Mateusz Sarzyński |

| Exhibition | Weltschmerz |

| Place / venue | Widna Gallery, Cracow |

| Dates | August 31 - September 30, 2018 |

| Curated by | Agnieszka Jankowska-Marzec |

| Website | www.widna.pl |

| Index | Agnieszka Jankowska-Marzec Mateusz Sarzyński Widna Gallery |