Foreword: Dialectics of Sight

LEWIS R. GORDON

“The first to die in the struggle against fascism were communists.” These were the words Paul Robeson spoke when testifying in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956. Robeson went on to explain his political affiliations in relation to that struggle: “My father was a slave, and I stand here struggling for the rights of my people to be full citizens of this country. And they are not…. In Russia, I felt for the first time like a full human being…. I [remain in the USA] because I’m opposing the neo-fascist cause.”[1]

Discussions of the history of the Communist Party in the United States often ignore that it was—and continues to be—a multiracial organization since its founding in 1919. At times, its Black members constituted forty percent, and there was no shortage of Black leadership, as attested to by the jurist and politician Benjamin Davis and the organizer Angelo Herndon, straight through to prominent intellectuals—from Claude McKay to Robeson, Claudia Jones, and (until the 1990s) Angela Davis. This history attests to the entanglement of race and class, wherein to ignore the former is to distort the latter, especially in the American context.

The United States is not alone in this regard. Often ignored as a postcolony, that status brings the US into company with many countries across the globe that are former colonies of European empires. The imperial age from which these countries were born was marked by a conception of modern life that featured a confluence of secularized religious ideas in which certain groups, or properly “races,” of people were anointed agents of history. Among Iberian Christians who sailed to the shores of the Caribbean, these agents were those who were, unlike Jews and Moors (Afro-Muslims), not marked by raza. As agents of Christendom, they landed on seashores with Bibles, crosses, and swords held high, and implemented systems of exploitation. Taking the reins of history involved asserting the superiority of wealth, whiteness, and Christianity. A form of idolatry followed by which all converged into Capitalism, in which the saved are white and wealthy, and the damned are dark and poor.

Among the misfortunes wrought from the events of the fifteenth century onward were policies of genocide against the Indigenous peoples of colonies and the kidnapping of others into enslavement to provide the much-needed labor to fuel the growing system. This process resulted in a form of anthropological rationalization of the growing Euromodern system. Models of what it means to be human increasingly took the form of greed, narcissism, megalomania, and pleonexia (the belief in having the supposed “right” to everything). Although some may call these agents “capitalists,” they are in truth more than that, because what always haunts capitalism is its avowed divinity. The idea of a superior race of people to whom all the products of labor must be devoted transformed the theonaturalistic concept of raza (the Andalusian term for special breeds of horses and dogs) into “race.” “Theonaturalism” is the view that only beings created by a god are “natural.” Although economic location was evident, the rationalizations—posed as justifications—took the form of race. Race is the underlying anthropology of the Euromodern age. It distinguishes those who are within humanity from those who are outside it. Against those who are outside, at times, all is permitted.

The history of enslavement is one of exploitation and asphyxiation. Packed in the almost airless hulls of slave ships, the “cargo” captured to fuel production in the “New World” endured circumstances under which they could barely breathe. Many fought; others jumped ship when taken up deck to stretch their legs. Those who survived the torture, disease, degradation, and filth found themselves in a world of daily violence in which their survival depended on the knowledge they brought from Africa. Studies of enslavement often ignore a basic fact about the enslaved: they were skilled laborers. Those skills enabled their survival. They also ensured the survival of those who enslaved them. As with Native Americans, it was African knowledge that played a crucial role in settler prosperity. And as with Native Americans, the shame of that dependency meant a constant rewriting of history and truth to match the need for positive self-images among settlers, exploiters, and their ruling elites. History was white-washed as a march of freedom and progress. Reality proved otherwise, as that history was also an effort to make rigorous technologies of dehumanization, enslavement, and the rationalization of historic lies.

“I can’t breathe” is a theme throughout. Wherever enslavement was outlawed, lynchings and other forms of violence followed against the legally “freed.” Fighting for dignity, respect, and survival along the way, there was no question of a racial struggle amidst a class one. Given the overwhelming location of Black peoples among the poor and laboring classes, the disaggregation of race and class was for them a ruse. As the economist Oliver Cromwell Cox put it, Euromodern capitalism includes the proletarianization of a race.[2] This insight was shared among so many others from Rosa Luxemburg, to W.E.B. Du Bois, to Eric Williams, and its truth comes home to roost through the history of Jim Crow (or American apartheid) to the many white-dominated riots that destroyed prospering Black communities in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in Jacksonville, Florida, and across the United States. The logic was that formerly enslaved people must not prosper. There was a need for Black failure, as it supposedly “proved” an intrinsic incapacity of people of African descent and thus the legitimacy or exculpation of the unfortunate history that transpired.

An odd characteristic of human beings is that when treated with dignity and respect—that is, as human—we grow. When denied our humanity, we wither. This is odd because human beings are aware of being human throughout. Why should it matter that we be treated or recognized as such? The answer is ancient. From ancient African to Asian and Indigenous American thought, the human being is not a thing but a relationship born from communities. This understanding is part of what Karl Marx was getting at in his articulation of human flourishing and also dialectical thought. Non-dialectical thinking leaves ideas and people trapped in the binary logic of contraries produced by universal positives and their absence: universal negatives. Each becomes universally separate or sealed unto themselves. But the human world is dialectical and interactive. This is evident in touch, speech, love, and culture. Combined, these sensory and social actions build human worlds that enable us to transcend our physical space. This transcendence takes the form of rules, laws, knowledge, art, and the whole constellation of meaning through which human beings live beyond the biological mechanisms of life. To be denied these pushes us into ourselves and away from the human world. That inward movement is a form of withering to a point of implosion.

Where air is lacking, we must go elsewhere to breathe. The struggle for air is there in the many revolts throughout enslavement, including the great Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), through to the myriad institutions built across the globe to channel freedom and de facto democracy. Among these was the Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent forming of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or, simply, Soviet Union (1922–1991). Aware of the proletarianization of people of African descent, the Soviet Union was an ally of Black liberation causes, which attracted the radical Black intelligentsia. That intelligentsia brought all their resources to bear in the fight for freedom. This meant each was a convergence of multiple activities of the mind and heart. Distinctions between artist and scientist, lawyer and activist, preacher and laity, athlete and intellectual, were transcended in the open dialectics of the struggle for liberation.

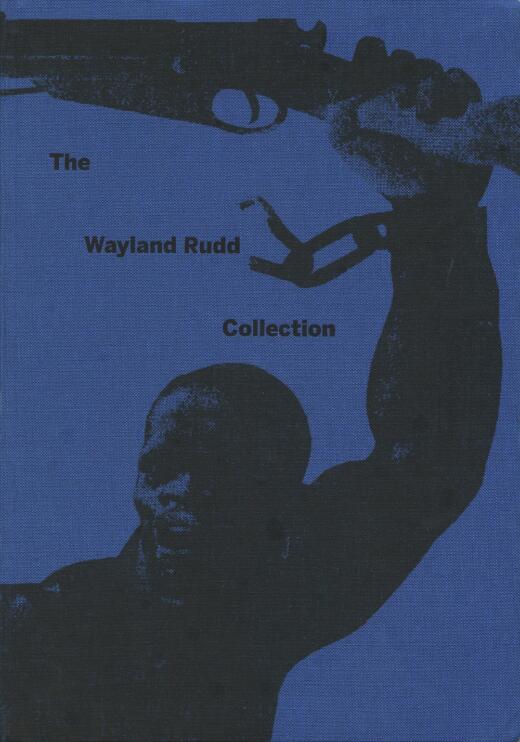

Wayland Rudd (1900–1952), a Black actor from Lincoln, Nebraska, received critical acclaim for his performances in Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (a role that went to Robeson for the 1933 film adaptation) and in Shakespeare’s Othello. Despite some success on the American stage, he was among those who sought solace in the Soviet Union. He went to Moscow in 1932 with Langston Hughes and a group of twenty-two performers for a film project called Black and White that was meant to expose American race issues. Though the project fell through, Rudd remained there, finding work with theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold and playing a Black convict in the 1933 film The Great Consoler, under the direction of Lev Kuleshov. He returned to the States in 1934, married and with a daughter. One could imagine the challenges the couple faced upon their return to a country in which Black men were being lynched for even looking in the direction of white women. At home, he voiced his opinion on working conditions in the United States for Black actors, characterizing the Soviet theater as “liberated” with regard to race, and suggesting that multiracial casts and Blacks in leading roles didn’t pose a problem in the USSR. Rudd then returned to the Soviet Union in 1936, without his wife and child, becoming a Soviet citizen and renouncing his US citizenship in the late 1930s. During World War II, he entertained the Soviet troops at the front line. He married a fellow American expatriate, Lorita Marksity, a pianist of Eastern European descent, with whom he had two children. He achieved professional success in the Soviet Union, performing on the Soviet stage, appearing in films, earning a degree in directing, and writing and directing his own plays, including one based on the life of Black labor organizer Angelo Herndon.

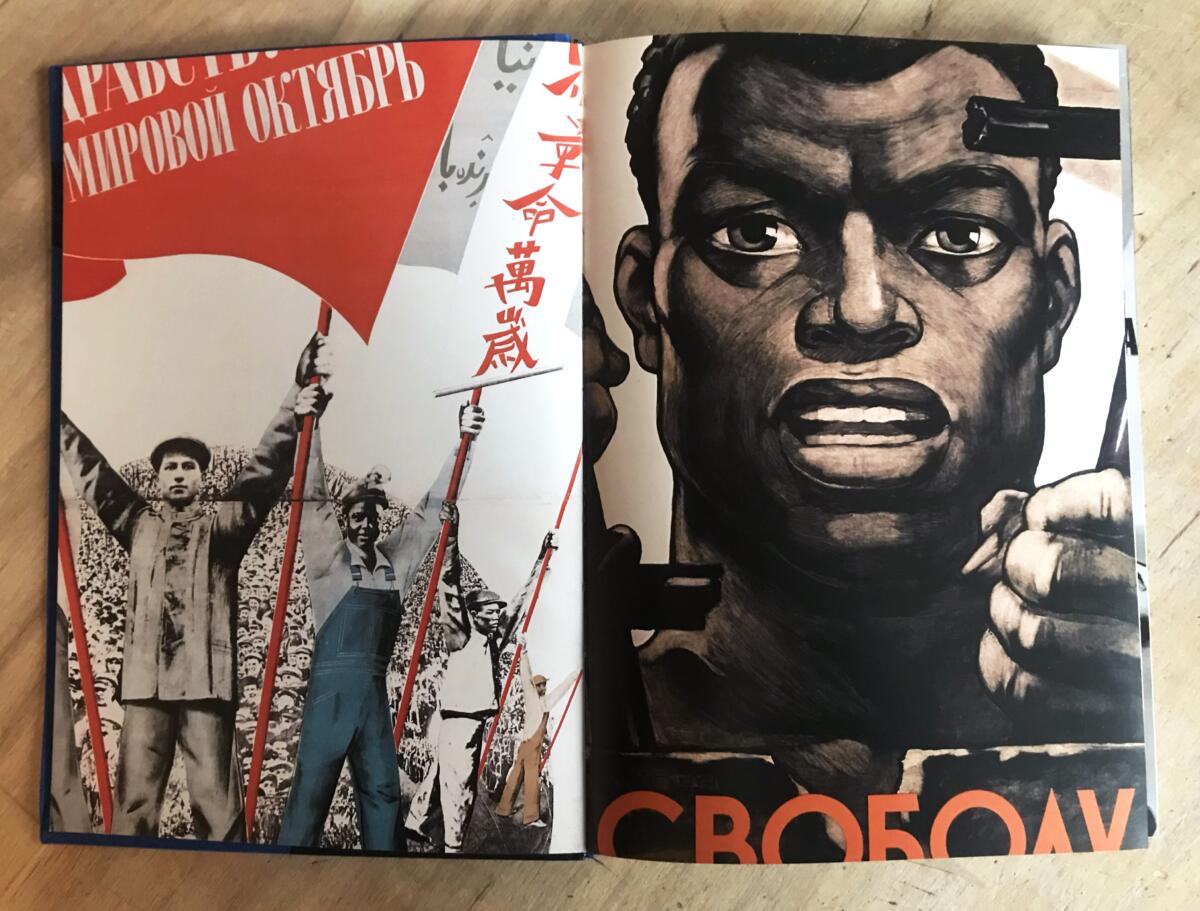

The present collection, titled in honor of Rudd, offers a portrait of racial ideology, especially with regard to Blacks, in the Soviet Union. It should be borne in mind that people of African descent in Russia preceded the USSR and also the times of Euromodern colonialism. That complicated history is marked more by their Russianness than their blackness. The point at which blackness is at issue is that of its historical degradation. It is the point of Black melancholia, where “negroes,” “niggers,” and “blacks” are white constructions of antiblack society. This makes that kind of blackness indigenous to a world that rejects it. This theme of rejection is marked by dehumanization. It stimulates an urge for belonging. While some sought belonging in Sierra Leone and Liberia, the path for others, because of their professions, led them to Europe—from Weimar Germany to pre-Vichy France to, as this collection attests, the Soviet Union. Intellectuals from South and East Asia followed similar paths.

Criticisms of these expatriates are many, especially since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 left historical interpretation to a triumphant eschatological capitalism and mostly neoliberal and neoconservative scholarship. In popular culture, some groundwork was set in the 1985 film White Nights starring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines, in which Hines’s character, Raymond Greenwood—a Black American dancer and actor who expatriated to the Soviet Union—comes to see, through Baryshnikov’s Nikolai “Kolya” Rodchenko, the disingenuousness of the USSR’s embrace of the African diaspora.[3] While Russian racism comes to the fore in the film, the strange message of fleeing back to the United States offers Black audiences no solace. For what, then, is the conclusion but that socialism offers no more freedom for Black people than any other system so long as there is white domination? The weird message seems to be that it is better to be degraded under capitalism than under socialism, even with the many infrastructural guarantees of the latter. Part of US propaganda throughout the Cold War was to make the German Democratic Republic (GDR) representative of the Socialist countries of Northern Eurasia. Not mentioned in these portraits is the extent to which the USSR had a great incentive to make the lives of their former German enemy—which, we should remember, killed 30,000,000 Soviets in WWII—miserable. Still, the false dilemma of USSR or USA sets the stage for limited racial vision. Post- Soviet Russia, as we now know, fosters fascism and racism under Vladimir Putin’s leadership, just as neoliberalism prepared the ground for neoconservative and fascist agendas to take root in liberal democracies. By 2020, as many across the globe took to the streets after witnessing the asphyxiation of George Floyd under the knee of a police officer in Minneapolis, the message against antiblack racism points to an ideal beyond both the former USSR and the current USA: democracy.

Blacks live the contradictions of Euromodern society. What is liberation but, in metaphorical terms, fresh air? And what is oppression but disempowerment through which the ability to breathe decreases? What is the fight against oppression but the fight for empowerment? And what is most feared in societies premised upon the disempowerment of Black people other than Black Power? That power is often misunderstood as Black domination. Black Power, by contrast, is the ability to render antiblack racism impotent. The fear of antiblack racists isn’t whether Black people hate or love them. Their ultimate fear is their own irrelevance. That cannot be achieved through making them the focus; it is achieved through building a system in which they are no more powerful than others. Where everyone else is devoted to democratic flourishing, agents of inequality lose sway. The Euromodern age, despite its use of “democracy” as a mantra, is antidemocratic so long as it remains committed to the disempowerment of Black and Indigenous peoples. Its opposition is the radicalization of democracy. People today are fighting for democracy, under the banner of “Black Lives Matter,” in an effort to breathe, which is no understatement in a time where the COVID-19 pandemic is worsened by inept and often malevolent leadership. How else can this be done but through struggle?

Visual Art Responses to the Wayland Rudd Collection

YEVGENIY FIKS

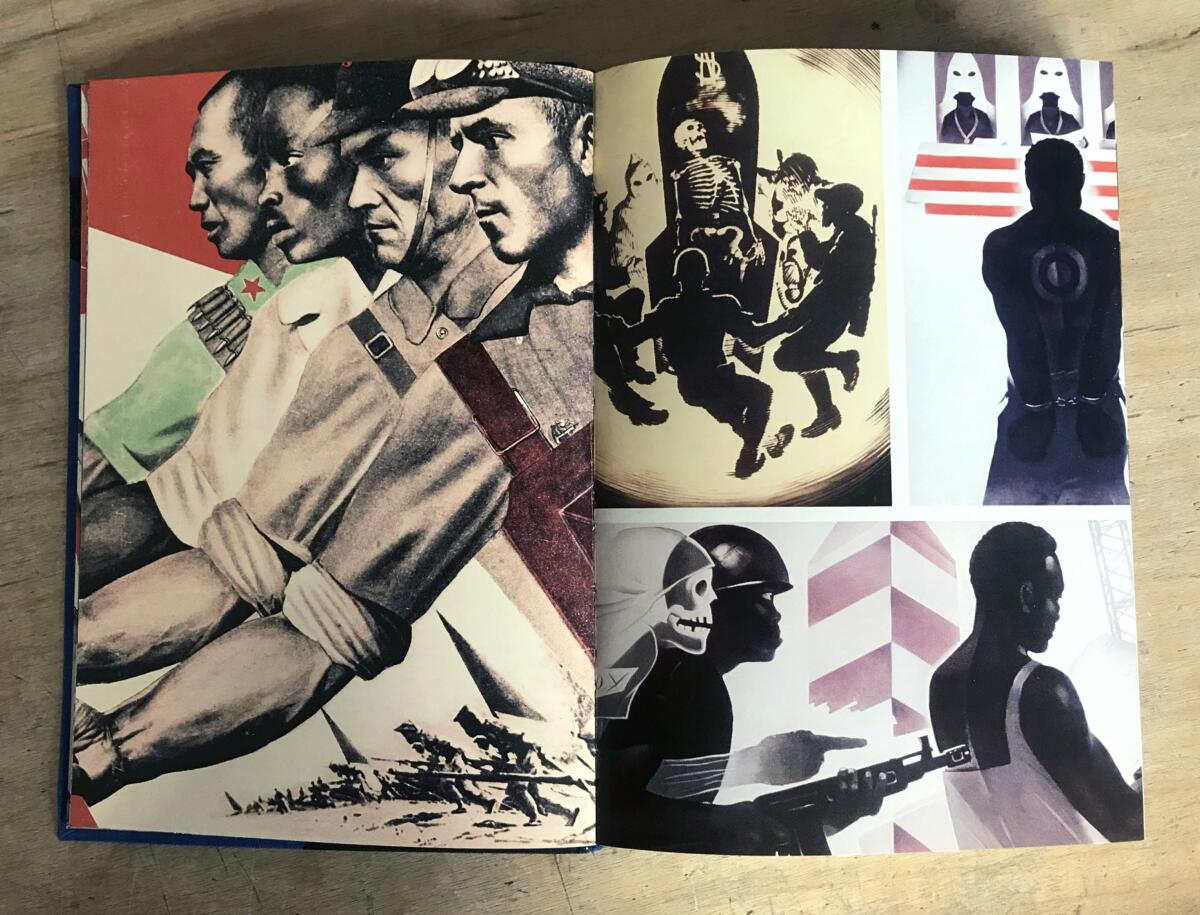

Around 2013, I asked thirteen contemporary artists and artist collectives to contribute work that responded to images in the Wayland Rudd Collection for an exhibition which was shown first at the Winkleman Gallery in New York[4], in March of 2014, before traveling to Zimbabwe’s First Floor Gallery in Harare.[5] Among the participating artists were Ivan Brazhkin, Michael Paul Britto, Suzanne Broughel, Maria Buyondo, Zachary Fabri, Joy Garnett, Alexey Katalkin, Kara Lynch, Nikolay Oleynikov and the Arkadiy Kots Band, Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Gluklya), Jenny Polak, Dread Scott, and Haim Sokol. This heterogeneous and international group of artists—each with a history of handling relevant subjects such as multiculturalism, American and Soviet history, revolutionary art, and race representation—was chosen in the interest of bringing a breadth of perspectives to the images in the archive. In what follows, I’d like to describe the works contributed; the thematic divisions reflect the ways I think the works came together.

Post-Soviet: Mourning Solidarity

Ivan Brazhkin’s video work, Tito Romalio, is a response to the themes of internationalism and international friendship that are common to many works in the Wayland Rudd Collection. This work takes as its subject the violent death of a Soviet Afro-Brazilian child-star who became famous in the 1960s for his roles in propaganda films about internationalism and friendship between peoples of different nationalities and races. In the early morning of May 10, 2010, many years after his early film career, Tito Romalio was shopping at a major supermarket, Perekrestok, in Saint Petersburg, Russia. There he was severely beaten during an attempted mugging. Ramalio was taken to a hospital but remained unconscious until he died the next day. Brazhkin’s video interweaves security camera footage of the beating with idealistic scenes from Romalio’s 1960s films. The video installation included a stack of pocket calendars with the date of Romalio’s death marked in red which visitors were free to take.

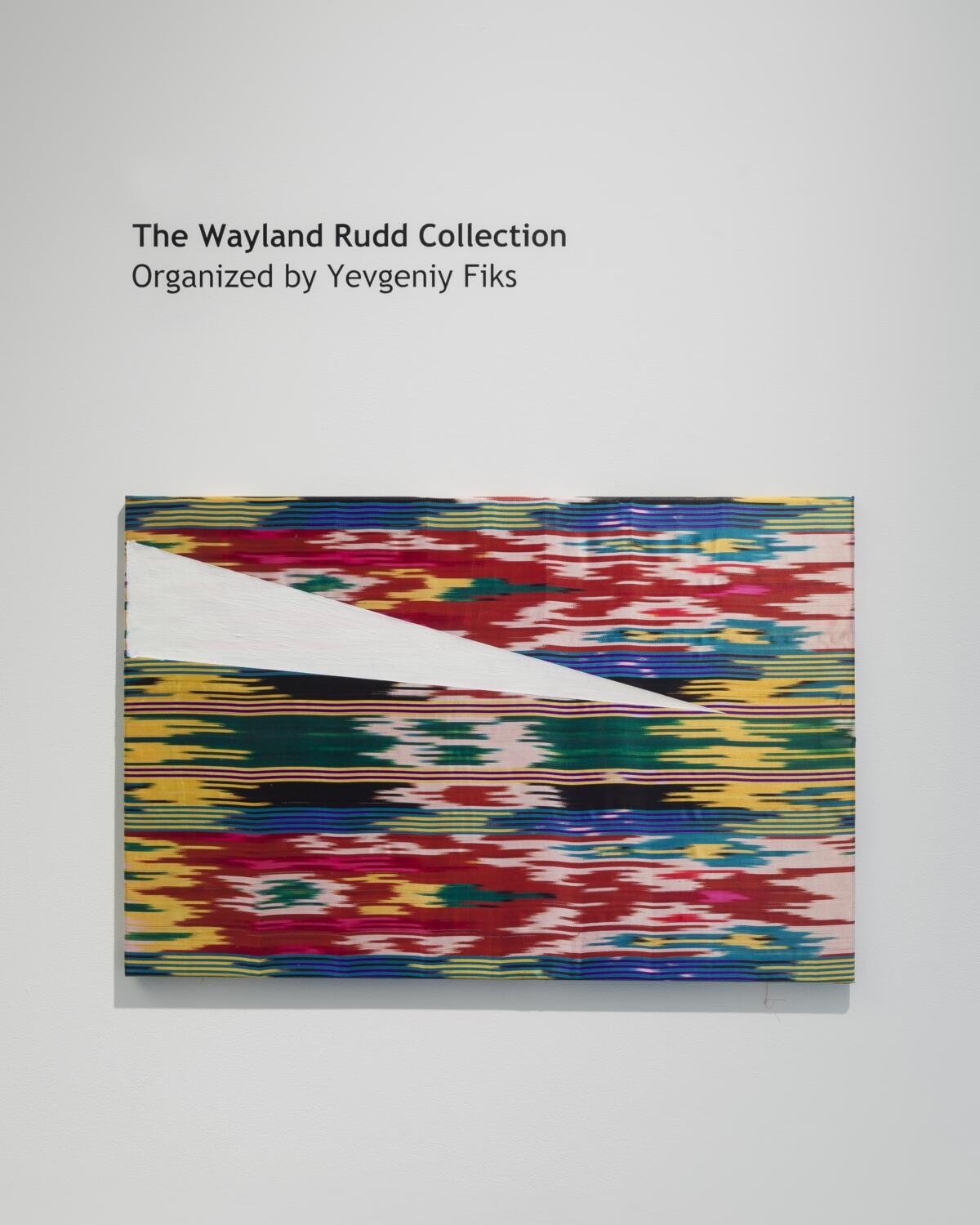

Alexey Katalkin’s painting Searchlight combines two visual elements: a large beam of light appropriated from a Soviet propaganda poster is superimposed on a traditional Uzbek fabric, died in bright reds, yellows, blues, and greens. The propaganda work Katalkin references is V. Boldyrev’s 1969 poster, “The great Lenin lit the way for us”, which depicts an African liberation fighter backgrounded by a beam of light emanating from a naval ship, the Aurora, the Russian armed cruiser fabled for its role in the October Revolution. By juxtaposing these two elements, Katalkin’s painting evokes the contraditions between the anti-racist, internationalist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperialist stances of Soviet propaganda with Soviet-era colonialism and imperialism towards Soviet territories of Cental Asia, and post-Soviet racism towards migrants from now independent Central Asian countries, such as Uzbekistan.

Katalkin’s sentiment of mourning the post-Soviet loss of solidarity between Russians and formerly Soviet Central Asians is echoed in a video work by artist Haim Sokol titled Spartacus (Scenes from Roman life. Based on the Soviet ballet “Spartak” (1954) by Aram Khachaturyan. Dedicated to the 70th Anniversary of the Uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto). At the intersection between documentary and theatrical performance, Sokol’s film restages the Spartacus-led gladiator rebellion of 73–71 BC in contemporary Moscow, and, in the artist’s own words, “simultaneously in the revolutionary past and maybe in some unpredictable future,” where Kirghiz migrant workers play both Romans and gladiators.

Dissecting Propaganda, Constructing Images Politically

Jenny Polak’s Category Crush is an animation/video that co-opts the format and sound-effects of the popular iPhone “matching” game “Candy Crush” as a platform for perusing images in the Wayland Rudd Collection. The video creates the illusion of an invisible player sorting images from the Collection into a series of ironic, Black-themed categories, such as “Exotic,” “Down,” “Entertaining,” “Bad,” and “Colorful.” The categories are announced by writer, actor, and vocalist Carl Hancock Rux in a manner that recasts the game’s lugubrious voicings.

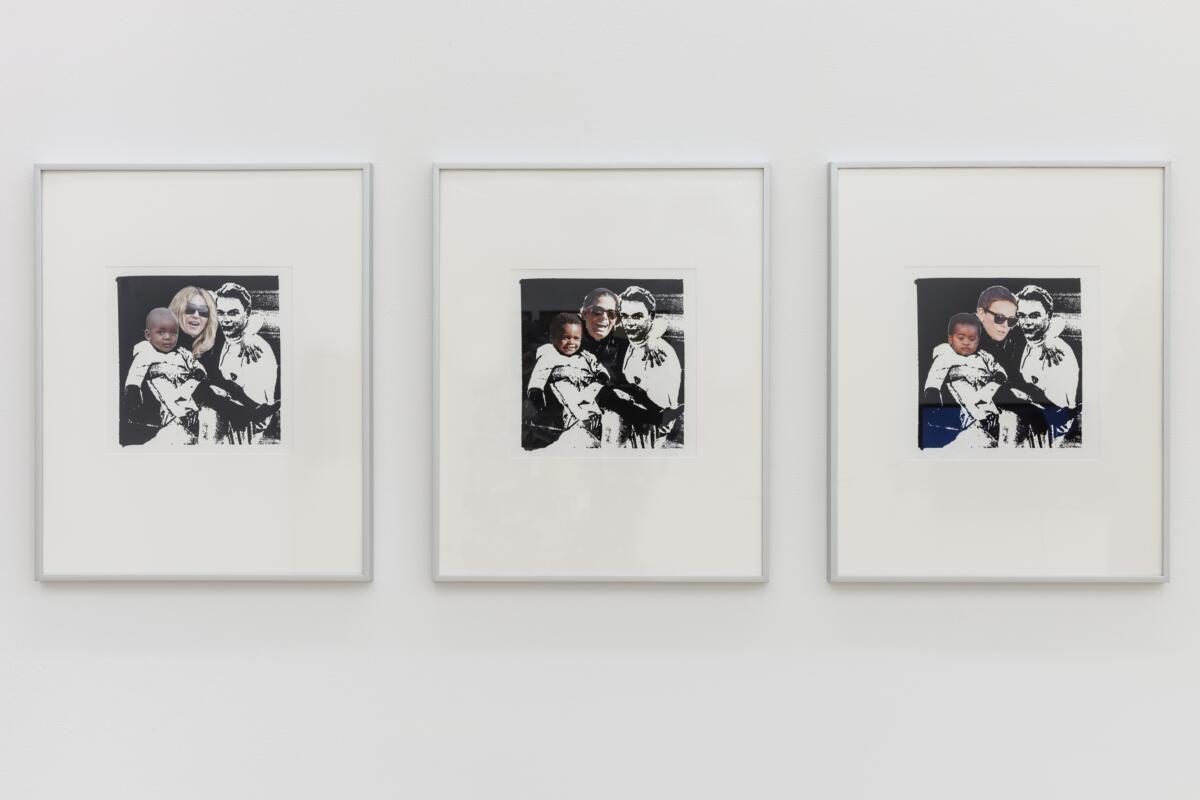

Michael Paul Britto’s three collages, collectively titled Tsirk Recast, are inspired by the 1936 Soviet film Circus[6], which tells the story of a white female trapeze artist, Marion Dixon (played by Lyubov Orlova), who becomes the victim of racist attacks in the US after giving birth to a mixed-race child. Marion travels to the Soviet Union and settles in Moscow where she and her child find refuge and social acceptance. Britto used a still from the closing scene, in which Marion embraces her Russian husband Ivan (played by Sergei Stolyarov) and her son Jimmy (played by James Patterson). This iconic Soviet image of a racially mixed family provides the undergirding for Britto’s collages of white American actresses (Madonna, Sandra Bullock, Charlize Theron) and their adopted Black male children.

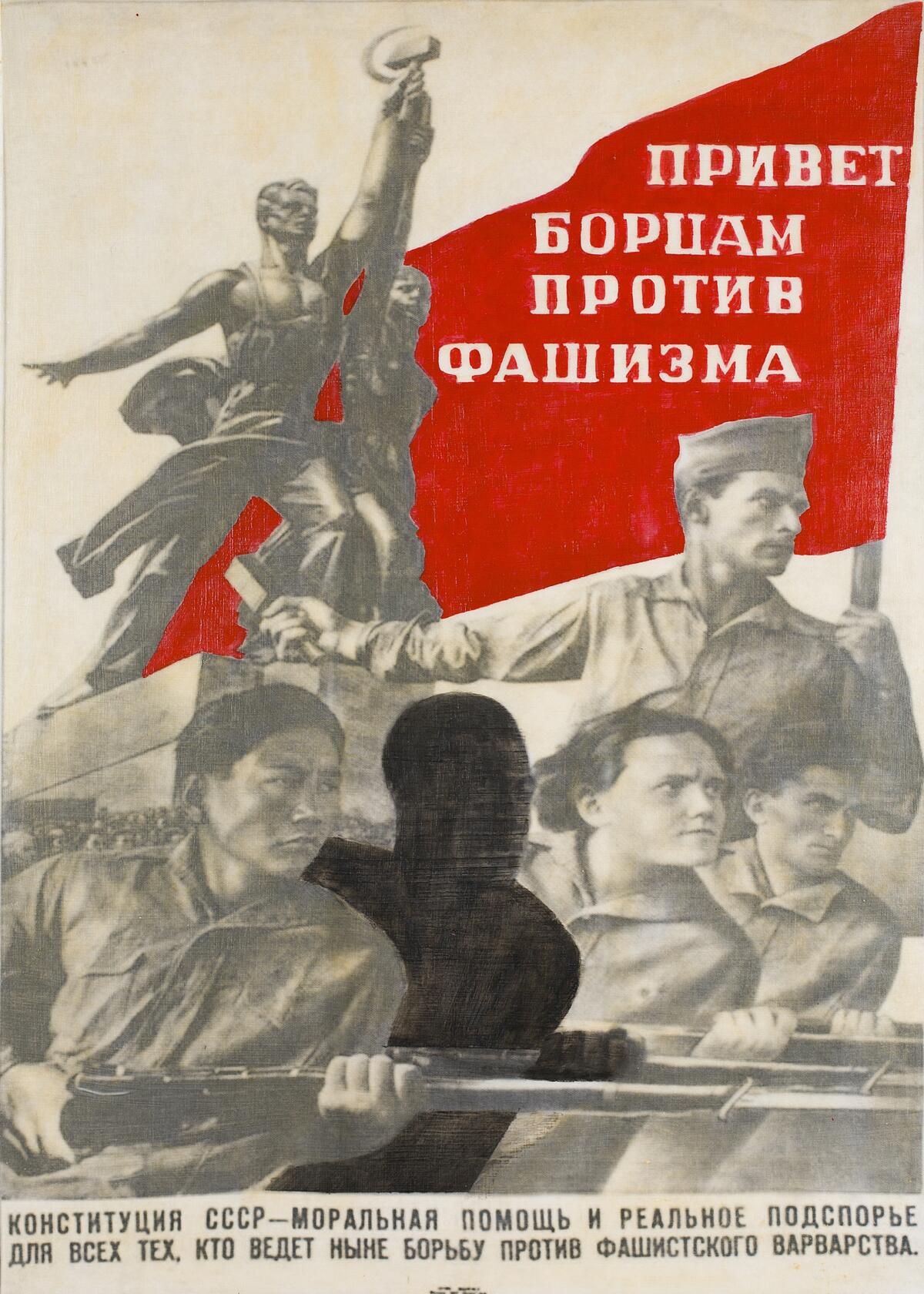

Dread Scott’s paintings, Constitution of the USSR and Internationale Will Be, are based on a poster (Greetings to the Fighters Against Fascism) and an oil painting (A Song of Peace: Paul Robeson in the Pickskills, USA) from the Wayland Rudd Collection. Scott made various interventions into these images by filling in all the images of Black people with black or red silhouettes and sometimes removing or deleting other elements, leaving white blanks in their place.

Zachary Fabri, My Grandfather Was a Black Communist, courtesy of the artist | photo: Etienne Frossard

Zachary Fabri contributed a suite of works on paper, My Grandfather Was a Black Communist, which focuses on the political militancy of Black activists who were inspired by Communism, such as Angela Davis and Paul Robeson, and the evolution of their political activities. Fabri is specifically interested in exploring how the influence of the Communist Party USA helped to catalyze the Civil Rights movement, “while also having its own long term agenda.”

Personal Histories

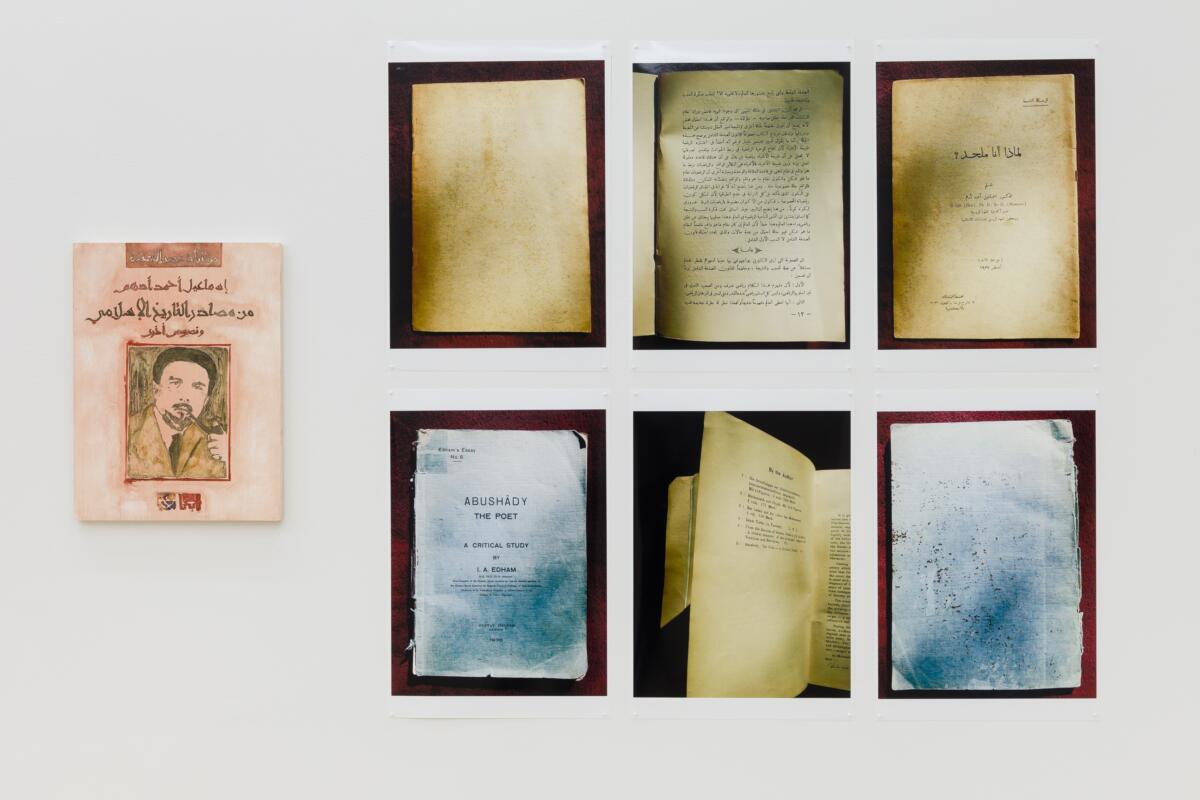

Maria Buyondo’s installation work, Pushkin, Winter Morning, is a reflection on the artist’s personal encounters growing up as a biracial person in the Soviet Union. In the video, Buyondo attempts to recite a poem by Alexander Pushkin that she had to memorize as a first-grader in Moscow in 1989. The artist fails to get beyond the first verse and is forced to start over again and again. According to Buyondo, “the repetition surfaces feelings of stress, frustration, and the unnerving sensation of being put on display.” As part of the installation, in addition to the video, Buyondo exhibited a Soviet schoolgirl’s uniform and a group photo of her first grade class in Moscow with herself—the only Black person—in the center. In two works, Edham the Atheist and Edham the Orientalist, Joy Garnett draws on the life of Alexandrian-Egyptian writer and provocateur Ismail Ahmed Edham (1911–1940), known for mythologizing his own life story. Though he claimed in his autobiography to have attained advanced degrees in physics, math, literature, and Islamic studies in the Soviet Union between 1931 and ’34, some scholars suggest that Edham never left Egypt. Edham is mostly remembered for his polemical treatise Why am I an Atheist?, printed and published in 1937 by The Cooperation Press, a publishing house on the rue de France in Alexandria, which was run by Garnett’s grandfather.

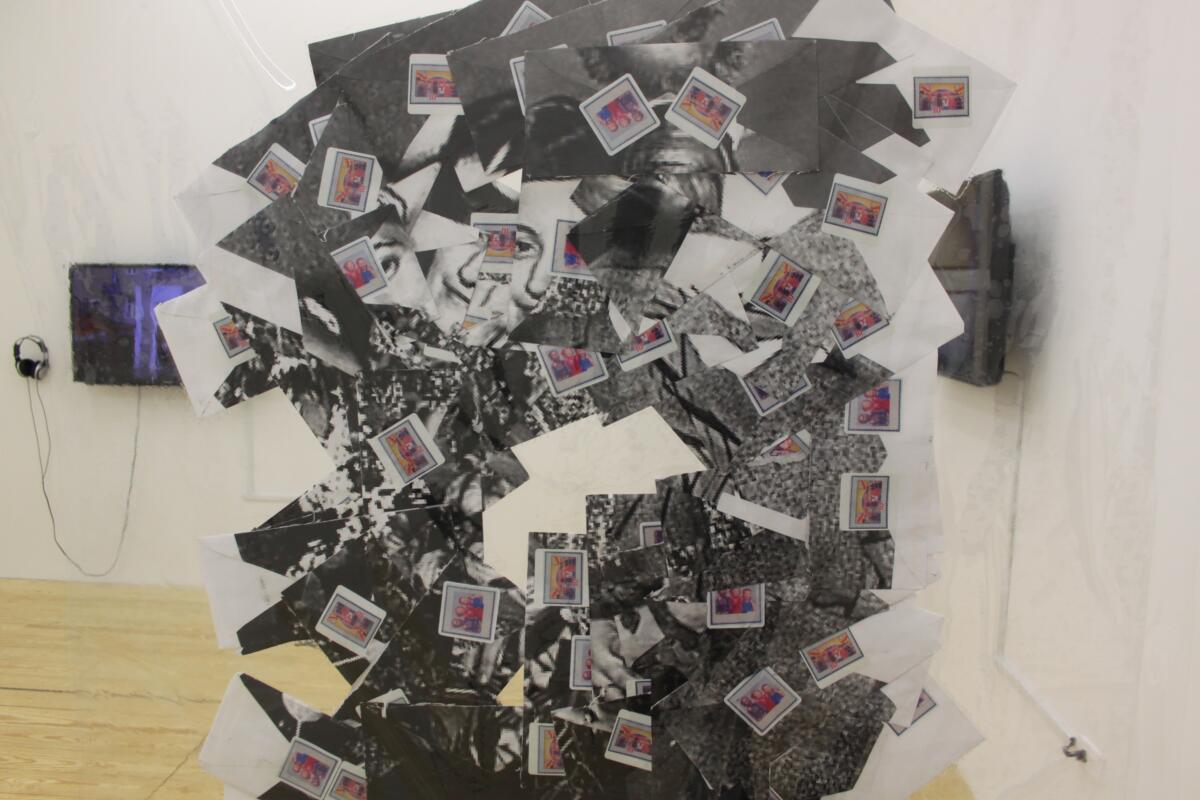

Suzanne Broughel’s installation Mail Conversation (for Wayland Rudd) is inspired by postage stamps in the Wayland Rudd Collection. In particular, the artist was struck by the appearance of Nelson Mandela’s image on Soviet stamps during his imprisonment in the 1980s. This gesture of support for the anti-apartheid movement was also typical of the Soviet Union’s propaganda tactics to discredit the US (and its support of the South African government) during the Cold War. Broughel printed an enlarged photograph of Wayland Rudd with his wife Lorita Marksity. She then cut the photo into fragments from which she made postal envelopes. In these custom envelopes, she sent letters to people with personal ties to the Rudd and Marksity; they were invited to write down their stories about the Rudd family, and to return these to Broughel in the same envelopes for inclusion in her installation. The reassembled envelopes were displayed as a fragmented collage portrait of the couple.

Russian Journal 1989–1999, is a conceptual piece presented under the authorship of “Kara Lynch in collaboration with ‘the Archivist/Curator.’” The work is subtitled “A group of artifacts under consideration for archival preservation to document the ‘Russian decade’ of the artist, Kara Lynch.” The work contains video footage filmed between 1989 and 1999 in the Soviet Union and Russia for Lynch’s groundbreaking, experimental documentary film, Black Russians. This footage, which has gone mostly unseen and untouched for twenty years, appears alongside the artist’s extensive archive of materials from that time—sketchbooks, journals, editing logbooks, photographs, and souvenirs.

Collaging the Present, Rebuilding Solidarity

Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya’s (a.k.a. Gluklya) work, skirtpantaloon FFC item, is a playful fashion piece designed for a post-Soviet retiree/pensioner. Made out of a colorful, African cotton skirt appended to one leg of a pair of Soviet-era suit pants, the work undercuts fixed gender roles, while also suggesting a hybrid cultural identity.

Hughes Rehearsals is a sound piece by artist Nikolay Oleynikov and the political punk band Arkadiy Kots. It is based on a song from the band’s interpretations of poems by Langston Hughes. Recalling scenes of the Rolling Stones rehearsing in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1968 film Sympathy for the Devil, Hughes Rehearsals includes the musicians’ banter and exclamations. Oleynikov and the musicians of the Arkadiy Kots band recorded Hughes Rehearsals at a Moscow communal apartment kitchen, bringing to mind the late-Soviet dissident intelligentsia tradition of nighttime kitchen gatherings for poetry readings, songwriters’ recitals, and discussions of politics and art.

I did not know what patterns and responses might emerge from my invitation for artists to respond to the images I had assembled in the Wayland Rudd Collection. It turned out that, for the most part, the Russian artists in the show either mourned the loss of an internationalist solidarity that had declined after the break-up of the USSR, or sought to revive it by turning their attention to present-day racism in Russia itself. Meanwhile, the responses of the American artists were more diverse. Some avoided specifically engaging Soviet propaganda images directly and instead focused on personal narratives as a way of reactivating the Collection. (In this connection, Maria Buyondo’s highly personal project is perhaps a link between the two groups of artists.) Others attempted to create distance from these images through irony and pastiche. Still others, however, reaffirmed the relevance of the Soviet Experiment’s internationalist anti-racist work, uniting with their Russian counterparts in an urgent desire for a new, historically informed internationalist solidarity.

[1] Proletarian TV. “Paul Robeson testifying at the House Un-American Activities Committee (re-enactment by James Earl Jones).” YouTube video, 11:46. May 14, 2019, (https://youtu.be/akj4lrS1bFY).

[2] Oliver Cromwell Cox, Caste, Class, and Race: A Study in Social Dynamics (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday Press, 1948).

[3] See more on White Nights in Christopher Stackhouse’s essay in this collection.

[4] Installation images by Etienne Frossard, courtesy of Winkleman Gallery. Other images provided by the artists.

[5] I am grateful to First Floor Gallery’s curator Valerie Kabov who made it possible to bring the Wayland Rudd Collection show to Harare, and to artist Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude for participating in that show.

[6] For more on Circus, see Joy Gleason Carew’s essay in this volume.

Copyright © Yevgeniy Fiks & Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021

Foreword copyright © Lewis Gordon, 2021

Imprint

| Author | Yevgeniy Fiks, Lewis R. Gordon, Kate Baldwin, Jonathan Flatley, Joy Gleason Carew, Raquel Greene, Douglas Kearney, Christina Kiaer, Maxim Matusevich, Vladimir Paperny, MaryLouise Patterson, Meredith Roman, Jonathan Shandell, Christopher Stackhouse, Marina Temkina |

| Artist | Ivan Brazhkin, Michael Paul Britto, Suzanne Broughel, Maria Buyondo, Zachary Fabri, Joy Garnett, Alexey Katalkin, Kara Lynch, Nontsikelelo Mutiti, Nikolay Oleynikov, Arkadiy Kots Band, Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Gluklya), Jenny Polak, Dread Scott, Haim Sokol |

| Title | The Wayland Rudd Collection |

| Exhibition | The Wayland Rudd Collection |

| Place / venue | Winkleman Gallery in New York | Zimbabwe’s First Floor Gallery in Harare |

| Curated by | Yevgeniy Fiks |

| Publisher | Ugly Duckling Presse |

| Published | December 2021 |

| Website | uglyducklingpresse.org/publications/the-wayland-rudd-collection/ |

| Index | Alexey Katalkin Arkadiy Kots Band Dread Scott Haim Sokol Ivan Brazhkin Jenny Polak Joy Garnett Kara Lynch Lewis R. Gordon Maria Buyondo Michael Paul Britto Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Gluklya) Nikolay Oleynikov Nontsikelelo Mutiti Suzanne Broughel Yevgeniy Fiks Zachary Fabri |