The extended version of this text in Polish is available here.

In 1970, a group of Buddhist monks from the Shingon and Nichiren schools went on a pilgrimage to Japan, from Toyama to Kumamoto. They adopted the name Jusatsu Kito Sodan, i.e. Group of Monks Bringing the Curse of Death. It was one of the most radical but also poetic ecological and anti-capitalist manifestations in the history of Japan. Equipped with conch instruments and books with the curses of Abhichar (based on, among others, Vedic rituals from the 9th century), the monks wandered from factory to factory where they camped and performed their ceremonies. Their intention was to bring death to factory directors through prayers. The activities of Jusatsu Kito Sodan were a response to the environmental pollution and mass poisonings in Japan after a series of epidemics in the mid-1960s. New diseases appeared, such as itai-itai, caused by cadmium contaminated rice, a side effect of hard coal mining.

We live in a time of planetary change affecting each and every one of us. Climate change influences every sphere of life, including thinking about art: the systems of its production and distribution, its social function and its relation to other disciplines, especially science. The Penumbral Age is composed of artistic works from the last five decades, based on observations and visualizations of the changes underway on planet Earth. It provides a space for discussion on “managing the irreversible” and new forms of solidarity, empathy and togetherness in the ace of the climate crisis.

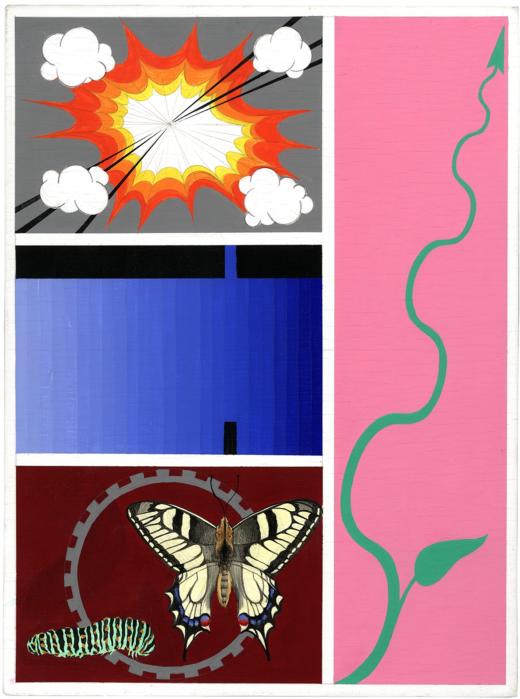

Kasper Bosmans, ‘Legend: A Temporary Futures Institute’, 2016, Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, Antwerp

The title of the exhibition is drawn from the book The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future by Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway (2014), where the protagonists from the future date the “period of the penumbra” from the “shadow of anti-intellectualism that fell over the once-Enlightened techno-scientific nations of the Western world during the second half of the twentieth century, preventing them from acting on the scientific knowledge available at the time” and leading to tragedy. We are witnesses to this process: scientific findings have ceased to be regarded as dispositive and do not persuade people to act. As the American writer and historian Ibram X. Kendi wrote in The Atlantic, analyzing skepticism about climate change or outright rejection of the threat (climate denialism): “Science becomes belief. Belief becomes science. Everything becomes nothing. Nothing becomes everything. All can believe and disbelieve all. We all can know everything and know nothing. Everyone lives as an expert on every subject.” The crisis in the culture of expertise and science is reinforced by fundamentalist movements denying such scientific findings as evolution and the harmfulness of air pollution, and disputing man’s impact on climate. Clearly, statistics, charts, graphs, and shocking photo and film reports from places affected by ecological disaster no longer make much of an impact on the imagination.

Observations by artists are akin to those of scientists, but they typically do not confront viewers with an excess of numbers, soaring bar graphs, or “pornographic” images of poverty and devastation. Art has “strange tools” (Alva Noë, 2015) at its disposal, which we can use to discern “wonders in the heavens and signs on the earth.” When ordinary tools of dialogue and persuasion fail, artists enable an “imaginative leap” by working on the emotions, confronting the incomprehensible and the unknown. As the theoretician of visual culture Nicholas Mirzoeff puts it, we must “unsee” how the past “has taught us to see the world, and begin to imagine a different way to be with what used to be called nature.” Art can help by organizing the work of imagination, sometimes more effectively than the tools developed by science and environmental policy.

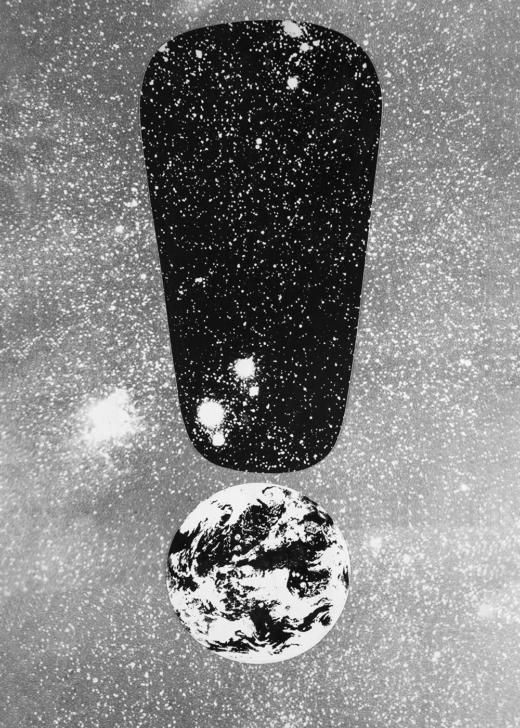

Rudolf Sikora, ‘Exclamation Mark’, 1974, Courtesy of the artist

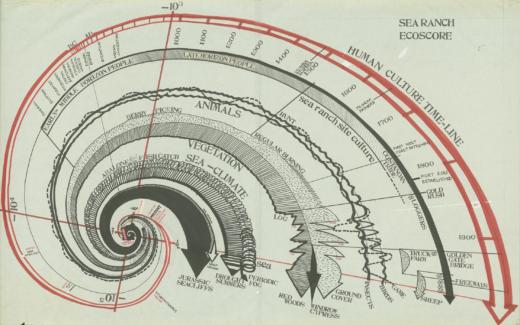

“The Penumbral Age” spans five decades, and highlights the strengthening of environmental reflections in the art of the late 1960s and early 1970s as well as the second decade of the 21st century. The first period is linked with intensification of pacifist, feminist and anti-racist movements and the formation of the contemporary ecological movement. The first Earth Day was held in 1970, Greenpeace was founded in 1971, and the next year a think-tank, the Club of Rome, published the report The Limits to Growth, describing the challenges posed for humanity by the exhaustion of natural resources. At the same time new artistic phenomena arose, such as conceptualism, anti-form, land art and earth art. While introducing “geological” thinking about art, artists used impermanent organic materials or sought to entirely dematerialize the work of art. Many of those proposals changed forever the thinking about the role of art institutions and the relationship between artistic practice, professional work, and activism. Mierle Laderman Ukeles, treating household chores and motherhood as part of her artistic work, Bonnie Ora Sherk, transforming urban wastelands into green oases, and Agnes Denes, combining art with cybernetics and agriculture, were all part of the countercultural revolution, which ultimately failed to live up to the hopes placed in it. For us, land art is much more than a stream of Western art emblematic of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Bonnie Ora Sherk, ‘Sitting Still I’, 1970, Courtesy of the artist

Following the thought of the Pakistani artist and activist Rasheed Araeen, drawing from his “ecoaesthetics” agenda, we seek “global art for a changing planet.” Araeen formulated an ecoaesthetics program, expressed in a series of essays making up the publication Art Beyond Art. Ecoaesthetics: A Manifesto for the 21st Century (2010). In it, the artist postulates going beyond the supremacy of the Homo sapiens species and unleashing the “creative energy of the free collective imagination.” Araeen’s program is anti-imperialist, anti-colonial as well as anti-capitalist. The system—wherein art functions— itself is criticized, which maintains hierarchies, glorifies growth and progress, powered by the intellectual fuel of modernity, separating creative energies from everyday life processes and petrifies them into “narego”—the narcissistic ego of the artist.

Akira Tsuboi, ‘Cruel contrast, the first person to escape’ (detal), 2016, Courtesy of the artist

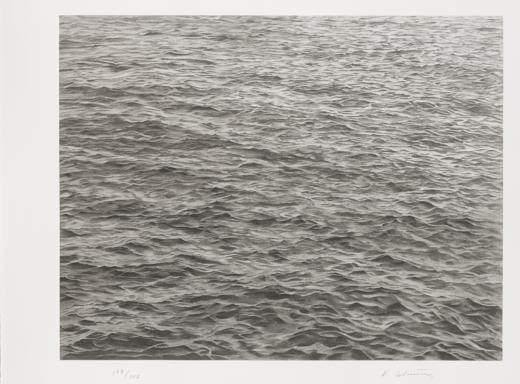

Actions connected with the “canonization” of land art, such as Richard Long’s Throwing a Stone around MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, in which the artist followed a stone he tossed before him, the “terraforming” plans of Robert Morris, or Gerry Schum’s television programme (an example of the use of new media to expose audiences to “organic” art practiced in deserts or forests), are accompanied in this exhibition by works from the 21st century, employing ecological education (Futurefarmers, Ines Doujak, the Center for Land Use Interpretation), protest (Suzanne Husky, Frans Krajcberg, Akira Tsuboi), and involving spirituality and esoterics (Shana Moulton and Nick Hallett, Teresa Murak, Tatiana Czekalska, Leszek Golec). Artists resort to refined and striking forms for conveying the changes occurring, such as field recordings (Anja Kanngieser), poetic textual reports (Hamish Fulton), drawings of dreams and visions (Manumie Qavavau), and installations from objects which the sea has tossed up on the beach (Simryn Gill). Their works help visualize what seems omnipresent and overwhelming. They may take abstract form, playing on the emotions and becoming an instrument of confabulation, as in the graphics by Vija Celmins, where a realistic composition presenting a view of the sea is in essence a study in constructing a vision of nature—much like the disk of ocean sounds from the environments series by Irv Teibel, an “assemblage” of recordings of waves from various sites, with different speed and frequency.

Vija Celmins, ‘Untitled (Ocean with Cross #1)’, 2005, Courtesy of the artist and Zuzāns Collection

In 1872 Claude Monet observed with delight the colours and light in the smoky sky over the port of Le Havre, which he captured in his famous painting Impression, Sunrise. In a work presented at the exhibition, Beautiful Sheffield (2001), by the contemporary British artist Tacita Dean, yearning for the irretrievably lost rural landscape of England, smog is simply smog, and grime accumulates as blackness across most of the composition. A series of works by Robert Barry from 1969 consisting of releasing inert gases into the atmosphere may be regarded today as a reflection on the theme of climate engineering, much like the diorama by Dora Budor filled with dust and pigments, into which acoustic phenomena from the construction site for the new building of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw are transmitted.This work turns us to the challenges connected with the museum itself and its new home on Plac Defilad—a huge development in the city centre.

Artists sensitive to environmental changes also address such issues as climate debt, postanthropocentrism, the unavoidable exhaustion of fossil-fuel deposits, the effects of limitless accumulation of goods and economic growth, planetary ecocide and colonial exploitation. All of this is the context for land art. We thus propose to extend this term to cover a broad panorama of artistic practices concerning humans’ relations with other species, inanimate matter, and the entire planet, as well as “nonartistic” ventures by artists and activists (from community gardens to the battle for the rights of native populations and the establishment of political parties). Land art in this sense is not confined to any one medium, specific material, or geographical region. It can also cover activities that do not occur under the banner of art. One example is the ice stupasin Ladakh, India, artificial glaciers created by engineer Sonam Wangchuk, with a fascinating form and a clearly defined function of delivering water to inhabitants of the desert at the foot of the Himalayas.

Ice stupa in Ladakh, fot. Sonam Wangchuk, 2015, Courtesy of the author

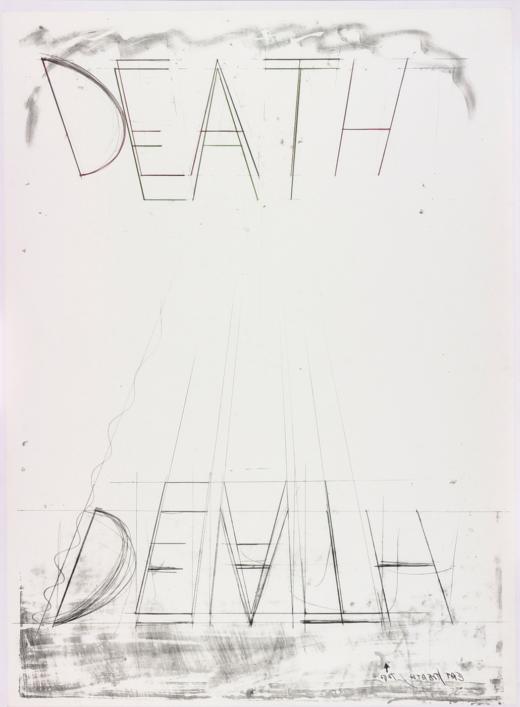

Time has never spun so fast. What used to take millions of year now plays out in just a few decades. In 1947 Isamu Noguchi proposed to erect Memorial to Man in the desert, a huge relief sculpture resembling a human face which could be viewed from space. It was supposed to leave a trace of a civilization that would seek a new home following a nuclear war by settling on Mars. But fantasies of “planet B” have not been fulfilled. We have just one Earth. The awareness of the catastrophic agency of the human species, as well as the inevitable end of the order we know, requires another view of the activity of mankind—a vision stripped of anthropocentric arrogance, non-human and closer to geology than the humanities. Only when we change our perspective and recognize that we live simultaneously on more than one scale will we perceive the consequences of the processes occurring since the Neolithic revolution (and later the industrial revolution and the post-war economic boom). The bounty we receive from “civilization” is also our poison. Eat Death, the American artist Bruce Nauman concluded in his prophetic work from 1971.

Bruce Nauman, ‘Eat Death’, 1973, Courtesy of the artist Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Life in a state of deepening crisis forces us to fundamentally change our thinking about the entire system of social organization and to confront ethical and existential dilemmas (climate migrations and new class conflicts). The world of art, with its museums and rituals for organizing objects and ideas, is no exception (to paraphrase the slogan of the Youth Strike for Climate, “No museums on a dead planet!”) and requires deep systemic transformation. We treat engagement in this discussion as a duty of the museum, and not as just another fashion or stream in art. Countering the calls for “ecological restoration” or the popularity of “art of the Anthropocene,” we stress the permenance of environmental reflection, based on continuity and responsibility. Our actions are part of a broader stream, counting on solidarity and cooperation, evident in the programmes and exhibitions launched in recent years at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, Biennale Warszawa, Galeria Kronika in Bytom, Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, BWA Opole, and other institutions throughout Poland.

Susanne Kriemann, ‘Ray’ (detal), 2013, Courtesy of the artist

Art will certainly not protect us against catastrophe, but it can help us arm ourselves with “strange tools” for the work of imagination and empathy. In her memorable manifesto from 1969, Mierle Laderman Ukeles posed the question: “After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?” In works of art from recent decades we not only seek a visualization of processes occurring on our planet, but also discern possible proposals for the future. If ecological catastrophe is already happening (as the residents of the inundated islands of Nauru and Banaba in the Pacific would certainly agree), together we wonder, will we ever manage to clean up our planetary mess and rebuild our relations with other sentient beings? Will we manage to start over again?

Anna & Lawrence Halprin, ‘Experiments in Environment workshop. Build a Driftwood City’, 1966, Lawrence Halprin Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania

Imprint

| Artist | Jonathas de Andrade, Isabelle Andriessen, Rasheed Araeen, Robert Barry, Kasper Bosmans, Boyle Family, Agnieszka Brzeżańska, Dora Budor, Vija Celmins, Center for Land Use Interpretation, Alice Creischer, Czekalska + Golec, Betsy Damon, Tacita Dean, Thierry De Cordier, Agnes Denes, Ines Doujak, Jimmie Durham, Jerzy Fedorowicz, Hamish Fulton, Futurefarmers, Cyprien Gaillard, Simryn Gill, Wanda Gołkowska, Guerrilla Girls, Małgorzata Gurowska, Anna & Lawrence Halprin, Mitsutoshi Hanaga, Suzanne Husky, Ice Stupa Project, INTERPRT, Anja Kanngieser, Karrabing Film Collective, Beom Kim, Frans Krajcberg, Susanne Kriemann, Stefan Krygier, Katalin Ladik, Nicolás Lamas, John Latham, Richard Long, Antje Majewski, Nicholas Mangan, Krzysztof Maniak, Qavavau Manumie, Robert Morris, Shana Moulton & Nick Hallett, Teresa Murak, Peter Nadin & Natsuko Uchino & Aimée Toledano, Bruce Nauman, Nishiko, Isamu Noguchi, OHO, Dennis Oppenheim, Prabhakar Pachpute & Rupali Patil, Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Agnieszka Polska, Ludmiła Popiel, Joanna Rajkowska, Jerzy Rosołowicz, Oscar Santillán, Gerry Schum, Bonnie Ora Sherk, Anna Siekierska, Rudolf Sikora, Magdalena Starska, Irv Teibel, Akira Tsuboi, Maria Waśko, Ryszard Waśko, Lawrence Weiner, Magdalena Więcek, Andrea Zittel. |

| Exhibition | The Penumbral Age. Art in The Time of Planetary Change |

| Place / venue | Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw |

| Curated by | Sebastian Cichocki, Jagna Lewandowska |

| Website | wiekpolcienia.artmuseum.pl/en |

| Index | Akira Tsuboi Anna & Lawrence Halprin Bonnie Ora Sherk Bruce Nauman Dora Budor Ice Stupa Project Isamu Noguchi Jagna Lewandowska Kasper Bosmans Mierle Laderman Ukeles Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw OHO Group (Nuša & Srečo Dragan Rasheed Araeen Robert Barry Rudolf Sikora Sebastian Cichocki Sonam Wangchuk Susanne Kriemann Tacita Dean Vija Celmins |