Belarusian writer Svetlana Aleksievich said that war does not have a woman’s face. Often, war and violence takes on purely masculine characteristics, where there is a triumph of strength, aggression, and masculinity. But war also has a feminine side, where violence against women and violence against nature is a phenomenon of the same order [1].

In Ukrainian cultural tradition, the image of women and the image of the earth have always been linked. Land or soil is represented as a woman. In literary tradition, there are numerous examples across historical periods where a woman’s body has been “torn to pieces” by men. The Ukrainian region of Donbas, which was once a strong industrial center, was in decline even before the seven-years war began. We peer into the Donbas landscape through works of documentary photographers, artists, and filmmakers to understand the tragedy of this region and its nervecenter: what can this post-industrial landscape riddled by war tell us? Through analogy in films, our imagination paints post-apocalyptic images with ruined houses. But referring to the history of the region, we can draw attention to the fact that the decline of these territories began long before the war. This is why the history of the region in the context of war is very important to understand the real situation there. Forgetting the history of the development and decline of the coal and metallurgical industries of this territory becomes easy through the lack of culture and the development of mythological thinking, the manipulations and imagination of others easily dominating media and society.

In the art world, the territory of Donbas has also been represented differently. For example, in Soviet visual culture, miners and metallurgists were often compared to Prometheus, an outcast and brave demigod. According to the legend, Prometheus created people from soil and gave them fire. It was this fire that became the symbolic embodiment of the mythological characters, which were interpreted by the Soviet propaganda machine as the personification of all those who worked the soil, extracting and processing metal and coal. The image of Prometheus as a miner was heroic and full of the utopian vision that glory, pride, and peace would always accompany people of this profession. In order to raise a family, people spent more time underground than on the surface of the earth. However, mortality in the mines has become one of the most critical issues of this region, both during the Soviet era and through to Ukrainian independence. The lack of modernization and concealment of the dangers themselves only exacerbated these features of the industry, to the point where the soil was increasingly taking the lives of its Prometheans.

With the outbreak of war in Donbas, the media began talking about dangerous mines being closed for good and people losing their jobs. For monocultural mining communities, this seemed like an imminent catastrophe. Even before the beginning of the war, many mines had been closed for some time and these shuttered, as well as new makeshift coal mines (pits, places of illegal coal mining), turned into safe houses and bomb shelters. People have gone down into the mines again, but this time in order to be saved.

The topic of the region’s natural and economic resources was crucial for Soviet propaganda. However, the theme of land use and depletion never came up, it was always hushed: the history of the region and ideology taught local residents to keep quiet about their problems, and to continue the silent rituals of exploiting the land and themselves.

The martial landscape and landscape violence are clearly visible through art and photography. Often the ruins of the destroyed and shelled houses become a metaphor for destroyed destinies. This is how we see Donbas and its inhabitants through a series of photographs by Alеna Grom[2], an artist from Donetsk who became an internally displaced person (IDP). In her project, Pendulum, Grom talks about personal experiences and analyzes the tragedy of an internal immigrant whose hometown has turned into the center of a war.

When war begins, life goes on. Grom began shooting her region with a camera as the war broke out: capturing its wounds, providing a counter to the military-centric media, showing instead the reality of everyday life — the simple lives of ordinary people who evade the meticulous eye of military cameramen. Grom captures every detail and passes it to the next generation.

Like most of her projects, Pendulum is an important finding for cultural historians because the author deftly reproduced it with the poetry of everyday life. This poetry is not always simple, and it occurs without rhymes and metaphors, but it is haunting nonetheless. The notion of a pendulum connects a series of diptychs. On the one hand, the viewer sees ‘skeletons’ (this is what Grom calls houses destroyed by war) and ruins, and on the other, the look of a child which contains hope for the revival of these ruins. While describing her project, Grom explains that nature is built on the principle of a pendulum, it is under its laws that war takes place and life is revived.

Grom’s heroes are the generation that is growing up through hostilities. In the center of her frame are children of war born under fire fighting and bombing from newborns, those who have already learned to walk and run, to adolescents in the ‘transitional’ age, with a rather specific and keen sense of love and awareness for its necessity. Another of Grom’s heroes is the land of Donbas itself, a native region, burned by war. In this photographer’s frame the land appears different from that of the military-centric media. It is not simply a war, it is an industrial-urban or rural landscape, full of love and suffering. The author’s view, like a pendulum, passes from one hero to another. Grom observes the generation and the region reflecting on how this war can eventually be won. This question is represented in one of her photographs through the symbolic visual of a baby lying on an old Soviet trade scale.

“War for a modern person has become a commonplace. When the war in Donbas had not yet begun but its approach was in the air, I dreamed that there were battles in the city. My family left before it became a reality. We went without looking back, abandoned the house and everything that we had. We thought only about the children and their safety. While taking pictures upon my return to Donbas I often met women with children. Children who were born during the period of hostilities. I asked, ‘How did women dare to give birth despite bombing, lack of medicine and elementary things? The danger is lurking at every turn for these people. It is terrible there. It is scary to live. How did they dare to take responsibility for another tiny and fragile life?’ Hearing different stories from people I have not found a general cause, except for one: nature is only governed by the laws of nature. Equilibrium is one of its main laws and man is a part of this nature, its child. An increase of the birth rate during war is a kind of nature’s response to natural destruction,” Grom commented[3].

This series of photographs is full of important symbolic details. According to the author, the square formatting of the diptychs, where each side is equal to the other, is a reference to this equality of forces — death and life. The square as a geometric symbol has an important semantic meaning that is also associated with equality, straightforwardness, order, monotony, and earth. The square embodies the main spatial landmarks organized in opposition. The square itself is the basis of many architectural constructions (ziggurat, pyramid, pagoda); altars are also square. This format also has a clear association in today’s internet-based world: the square images uploaded to the social platform Instagram have become a visual framework for the times we live in. Personal pages of people in the social network function as huge personal archives open to their followers through ‘square’ illustrations — their own memories, documentary, and historical evidence that require a new approach to reading and attribution. However, in contrast to the constant frames of luxurious buildings from tourist trips, the moments of happiness and success that limit our sight and ‘filters’ our ideas about the world, in Grom’s work, we are constantly at a turning point. Grom’s photography first refers to another reality, understanding of other social standards, of cultural situations and the Other. The modest bourgeois joy promoted by social networks and their love for brilliant life belies a lack of basic social guarantee, as well as security issues and economic problems.

The fragility and uncertainty of today is expressed clearly in a diptych created by Grom in 2018 featuring Mariinka and Krasnohorivka. On the left there is a portrait of a child: a boy in a colorful T-shirt and shorts poses at a playground that the viewer does not actually see. On the right side of the diptych the straight and colorful lines of his clothes are discolored and deformed. The author shows a house damaged by shelling. Grom peeps inside a room and finds nothing but broken shutters, no trace of people there. These blinds become like the shabby clothes of this house.

In the traditions of romanticism, ruins have acquired a special aesthetic value. The artists of this age saw in them a sublime beauty that harkened back primarily to ancient traditions. The fragments of buildings, like damaged human souls, conveyed the authors’ acute emotional experiences and their creative pursuits. Today, the ruin is part of our historical and cultural heritage. People are eager to photograph ruins resembling those in textbooks, admiring their beauty. However, they avert their eyes from modern ruins, and from the fact that day by day more of this overlooked debris is piling up. Of course, all these war-torn structures cannot be called an advanced architectural style, nor can it be said that they bear historical and cultural significance on a global scale. Nevertheless, these houses of ordinary people are modern monuments to violence and disorientation in the heart of Europe.

Alena Grom works with contemporary memory; she captures the events but adds commentary, so that the war in Donbas is not erased from historical and cultural memory. In his book Portraits: John Berger on Artists, art critic John Berger, described the work of an Italian painter, a representative of the Padova School of Painting, Andrea Mantegna (1430/31—1506), reflecting on oblivion and its tonality.

According to Berger, forgetting is embodied in the color blue, but then he adds that oblivion does not need shape; it is sculptural. For Berger, oblivion leaves traces similar to small white pebbles. Alena Grom’s diptychs are filled with light and bright, luminous colors. Warm shades of red and yellow create an opposition to the gradations of green and blue. Her works seem to be replete with air. One could say that they ‘breathe’. Grom’s light and bright pictures are a return from history. They are an attempt to talk about it while it is being created, and while the subject is ‘alive.’

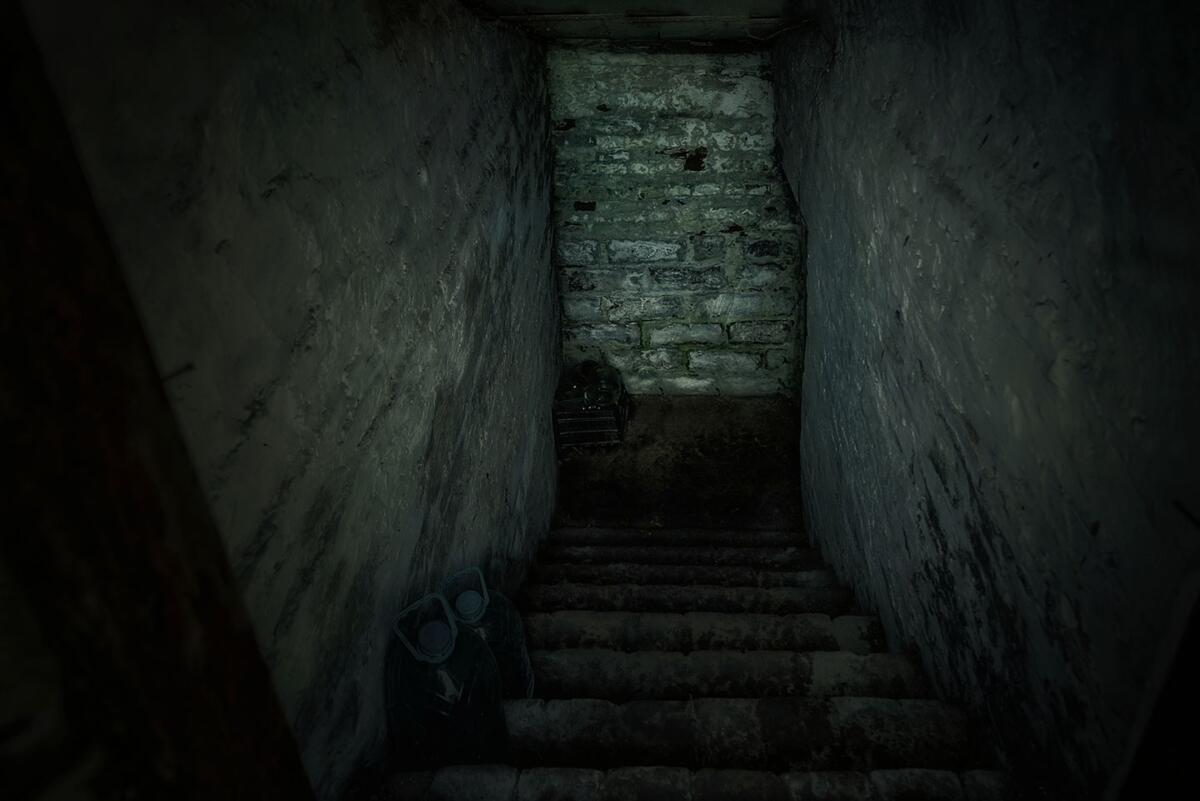

In her project The Womb, pictures are based upon the stories of women who decided to give birth while living in a war zone. Heroes of Grom’s photographs are both mothers and children of war, some of whom are more than four years old by now. These images show us how these children have spent their weekdays, how they learned to walk, talk, and experience life during the four years of military operations. The Womb is also a story of life in the face of death, war, and military violence. Despite choosing the genre of a portrait, the characters are not the only ones in her focus but also the notion of the ‘womb’ itself. A high-contrast spotlight conveys a special sensuality and drama built into the frame. Furthermore, it reveals the trust between the photographer and her subjects. Some frames are compositionally and emotionally reminiscent of the photographic stories by Gregory Crewdson, an American artist known for his scrupulous, static, surrealistic stories of American life. To some extent, Grom’s photographs may also seem surreal as they broadcast lives in a social crisis, showing a little personal happiness against a background of total poverty and devastation. However, Grom’s heroines also refute this surrealism. Such perception of everyday life is in fact quite real for them. “Well, how should I put it… they shot and fired. We were in the house, we went down to the basement. As for the rest we seem to be like everyone else: we live, we survive,” says one of Grom’s heroes[4].

Alena Grom explores the territory of Donbas as a living organism.The artist builds her work on medical parallels where soil and shelter take the literal form of an ultrasound of the abdomen. Residents of mining towns are an intrauterine fetus that develops and lives a full life, but remains in full dependence on its mother. Grom deliberately emphasizes the importance of human life and affirms it in her practice. How is it possible to help people who somehow wound up in a war zone? What is peace and what is the mode of life during the war? How can the war be overcome and how can people continue to live? It is important for a photographer to talk about the people who are able to survive war, and about a place that can survive time, rather than the causes of war and the displacement of the front. Alena Grom shows the transformation of this place. If before the coal mines were bringing grief and misfortune, under the conditions of constant, fierce attacks they have acquired a different meaning. For a long time a lot of families were forced to live in spaces that seem like dungeons: shelters, cellars, and even mines. They were forced to adapt their modes of living to these spaces, and the spaces shaped their whole existence. In this way, these spaces act as a womb, preserving and creating new life.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

[1] See, for example: Usmanova, Elvira. Violence as a cultural metaphor: instead of introduction. Original: Usmanova, Elvira. Nasilie kak kulturnaia metafora: vmesto vvedenia in Visualnoe (kak) nasilie. — Vilnius. — 2007. — P.10.

[2] ‘Notes from the Grey Zone: Interview with Alena Grom’ in In the In-Between. — 6 Mar. 2019. — URL:

[3] Interview with Kateryna Iakovlenko. March 2019.

[4] Interview with Alena Grom. May 2019.

Imprint

| Artist | Alena Grom |

| Website | alenagrom.com/ |

| Index | Alena Grom Kateryna Iakovlenko |