![The Documentary Turn in New Ukrainian Art [excerpts]](https://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/kulikovska-1200x1200.jpg)

The tensions related to the political transformations and war in Ukraine have provided the important background for a shift towards documentary art in the country. As the artist Mykola Ridnyi has remarked, “culture is not as lightning-fast as the media when there is a media war being waged.”[1] Ridnyi has pointed out that even though Ukrainian culture has been experiencing profound change, it is not fast enough in reacting to the ever-changing political and social situation. Documentary art—such as films, video works, and photography—can react faster than other practices because of their ephemeral temporal nature and their elimination of the necessity to process information in the way that a painting or a drawing does, constituting a particular “documentary turn” in the art that addresses political challenges. The researchers, curators, and artists who speak of the documentary turn in art, including Erika Balsom, Okwui Enwezor, Maria Lind, and Hito Steyerl, have remarked on the transformative role of documentary art practices, describing the latter as “a form that emerges in a state of crisis [and] often aims to mirror the effects of past or recent political and economic upheaval.”[2]

This research proposes the hypothesis that this ongoing documentary turn in Ukraine is a result of the necessity to record the traumatizing situation and interpret it using documentary art as an interdisciplinary medium. An artist with his or her lens appears as a mediator between the audience and the uneasy social and political situation surrounding them. In Ukraine, the documentary turn in contemporary art has led to the expanding use of digital media to report on the events that are transforming the political situation, creating the potential for social and cultural resistance, as well as an in-depth focus on existing archival materials. This process coincides in time with the increased global attention towards documentary art that has been conditioned by the development of digital humanities.[3] While digital humanities focus on work with a variety of documentary archives, the new Ukrainian art strives to organize such an archive from numerous perspectives. This task requires a long-term effort from creators, researchers, and curators in order to engender social transformations through art (as opposed to the documentary reflections of mass media that act within a short-term perspective) and to contribute to the preservation of cultural memory.

[…] Media scholar Olivier Lugon has pointed out that “‘Documentary’ is often taken as the antonym to ‘artistic,’ yet it stems primarily from the artistic field—beyond art, yet very much a part of it.”[4] Meanwhile, the film researcher Erika Balsom speaks of the new mobilization of documentary film in contemporary art, with the accessibility and “transportability” of the documentary helping to reach new audiences.[5] I propose that in the digital age, the exhibition space intersects with virtual space, and that this expands the possibilities for underrepresented documentary practices. For countries experiencing political and economic challenges, such as contemporary Ukraine, the mobility and visibility of documentary art becomes the principal instrument for the dissemination of information and the involvement of new audiences—not only in art but in the generation of knowledge about Ukraine’s identity.[6] With this research, I aim to contribute to the establishment of an expanded media field that would help to oppose the ongoing informational aggression from the Russian Federation.

Specifically, this article will justify the necessity of constituting and preserving Ukraine’s post-Maidan “cultural Renaissance” and explore the ways to do so.[7] Merging the documentary with art is essential because it expands the ways of presenting the newest practices and seeks new target audiences both inside Ukraine and worldwide, from cinema visitors to gallery-goers, to art and media researchers. The in-depth research in this field will help develop the perspectives on the future of Ukrainian art and its role in the formation of the Ukrainian national identity, within the framework of diversity provided by the pluralism of documentary practices.

[…]

Creating the archive

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine in 2014 brought a distinct focus onto filmmakers, photographers, and artists in terms of their creation of what Balsom and Peleg call “non-traditional forms of historiography.”[8] The former have created a visual account of the armed violence caused by the Russian occupation in the east and south of the country and documented the social tensions surrounding it.

The artist and filmmaker Mykola Ridnyi uses documentary methods to discuss complex social problems. He often merges fictional methods with archival footage to create a compelling and provocative story. Ridnyi’s project Armed and Dangerous (2019) gathered Ukrainian documentary film directors to create a series on the increasing militarization of Ukrainian society and the widespread access to firearms brought about by the war’s nearby frontline.

This project is collaborative, as it presents the documentary works of a number of Ukrainian documentary-makers and art filmmakers, including Oleksiy Radynsky, Piotr Armianovski, Oksana Kazmina, Elias Parvulesco, and Sashko Protiakh, among others. The seemingly disconnected stories in the resulting film reflect upon a variety of themes related to the discussion on the reasons behind and consequences of the military violence: from the cultural decay in the economically depressed regions of Ukraine to the re-emergence of the participation of far-right groups in the social and political life of the country. The episode by Oleksiy Radynsky is a compilation of archival recordings from Stanytsya Luhanska’s local museum and represents the tradition of sending local young men to the army in the 1990s. The artist depicts the grotesque syncretic mixture of the official events, which include ritualistic actions based on Russia’s Don Cossack references, 1990s pop music, and Orthodox religious rites. Radynsky questions the influences of nearby Russia on the (de)formation of the area and the post-Soviet economic and cultural decay, sharing the feeling of artificiality that characterizes the entire spectacle, as well as the marginalized nature and profound irrelevance of its participants.

The episode filmed by the filmmaker and performance artist Piotr Armianovski depicts the children of Slovyansk, which was occupied by pro-Russian forces in the spring of 2014 and three months after relinquished by the Ukrainian army. Children of different ages show their plastic guns and real knives and tell how they “play the war.” At some point, when the artist interviews a mother at the children’s playground, a former refugee who had had to leave the place because of the shelling, and, in her own words, who had been happy to return when the place eventually became safe. At this moment, her daughter arrives to tell her that the boys are threatening to shoot her with plastic guns. Hence, the artist contemplates the replication of violence that turns the victims into abusers—even if in a metaphorical manner, as part of a children’s game.

In its current reduced montage format, the project explores the grotesque side of abuse, as the narration turns to the themes of LGBT and feminist underground cultures, with their focus on their confrontations with ultra-right militarized groups, the latter of which keep receiving major exposure in the Ukrainian media by attacking art exhibitions and cultural events. The project touches upon the topics of gender and contested identities. The reduction of signification to one possible identity—whether related to politics or gender—is the aim of these groups. Ridnyi’s documentary project importantly raises concern about the amplified possibilities that the right-wing militarists have received because of the ongoing border war, which has appeared to “normalize” violence in an otherwise peaceful Ukrainian society.

Beyond this project, Piotr Armianovski’s short films exist on the edge of art and mass media. The film Mustard in the Gardens (2017) is an exploration into the life of its protagonist, a young woman named Olena from a village in the Donetsk region who gives a tour around her family house. The house that belonged to her grandmother is now locked up, as the frontline had approached the village, and the surrounding fields where Olena used to play as a child are now all mined. This touching account of a personal past destroyed by the war also contributes by recording the traditional village culture of the otherwise industrial Donetsk region—an invisible heritage that is in danger of being lost. Armianovski, from Donetsk himself, assumes a sympathetic position, as what he witnesses intersects with his own experience of leaving behind the past.

Similarly, the film Ma (2017) by Maria Stoianova looks at the world of conflict through the lens of another, direct, witness. The mother of her friend Zoya lives in Mariupol, on the edge of the war. The viewer sees how she cherishes the small pleasures of life, feeding the birds, caressing the cat, and walking in nature, in the times when she is not filming the shelling of her home city. Ricoeur’s notion of a “documentary proof” is once again useful here, as the rhetorical position assumed by the director of this short film is the evidence that is presented by the third party—an uninvolved, “naïve” viewer who at the same time appears as a reporter and interpreter of the traumatic events to the wider audience. The proof, taken with a simple smartphone, creates the value of the experience as well as its memory—inscribed in visual culture. The emotions transmitted by the camera involve the viewers, converting them if not into participants, into compassionate observers of the routine of the frontline city.

The interdisciplinary proposals of the latest Ukrainian documentary films yield extensive possibilities for the interpretation of this phenomenon through the lens not only of film studies but also art history and curatorial practice. The artist-filmmaker fusion is a powerful tool for the representation of existing narratives and, through this process, for the creation of new narratives that merge testimonies with their mythologized interpretations.

Displaying Ukrainian documentary art

The recent exhibition At the Front Line. Ukrainian Art, 2013–2019 (2019–20), which I curated at the National Museum of Cultures in Mexico City together with the historian Hanna Deikun, presented the challenge of displaying video art and documentary films, along with documentary photographs, in the museum space.[9] The first challenge of such an approach is the time that the audience is ready to dedicate to the works. Museum space is transitory space par excellence, a type of passage where streams of visitors are directed from room to room, and their attention is dispersed between numerous works. The display included such video works as Regular Places (2015) by Mykola Ridnyi, Iron Arch (2015) by Kristina Norman, the photographic series Victories of the Defeated (2014-2018) by Yevgenia Belorusets, and the media installation Simply Went Away (2014) by Olia Mykhailiuk, among others.

Balsom calls a film that can be presented in the gallery “the othered cinema,” pointing out the profound differences in its conceptual pursuits that result in new relationships with spaces and institutions that historically have not been part of cinematic experience.[10] In the case of the films by Ridnyi and Armianovski, this genre is also “othered” by the topics they address, focusing on the frontline experiences of the political conflict. The ways of displaying works that document reality are numerous, and the use of the museum space provides additional context to the otherwise cinema-based practices. This interdisciplinary approach facilitates reaching out to wider audiences, and places video production within the art historian’s domain of interest, representing a step forward towards greater interdisciplinarity.

For me, it was important to see what exactly constitutes the artistic element in the documentary works, what marks their pertinence to the domain of contemporary art as an alternative to the cinema space. This approach was at the core of the exhibition, which aimed to provide a basis for a different way of seeing, for example, the video-work, than in the experience provided by a cinema. Viewers typically spend less time watching the documentaries in museum conditions as they pass through space; however, what they obtain is the knowledge of a variety of visual representations that altogether form a coherent image of the conceptual, geographic, and cultural space in question.

Simply Went Away (2015) by Olia Mykhailiuk recreates the situation of the war in which the Donetsk and Luhansk Regions were immersed at the beginning of the confrontations along the Ukrainian-Russian border in 2014. The artist helps us to trace the tracks of the refugees from the Luhansk Oblast—many of them single mothers—who had to walk 40 kilometers in the snow, escaping the shelling of the cities. Mykhailiuk then created a seminar, as a kind of self-support group, where the women could narrate their stories and write them on a chalkboard. The resulting installation includes a two-channel video and charcoal inscription on the museum wall, quoting some of the stories. The artist here appears as a mediator between the viewers and the raw reality, blurring the border between documentary and fiction as she factually summarizes and replays the selected storyline formulated by the direct witnesses.

Yevgenia Belorusets’s series Victories of the Defeated (2014−18) explores the harsh reality behind the everyday routine of working-class people in the Donetsk Region. While having a general interest in the everyday lives of local miners within the context of the nearby war, the artist focuses on the social roles of the women who work at the mines. With an unrestricted insight into their personal spaces, Belorusets depicts an unembellished, raw reality of the conditions of poverty and hopelessness surrounding these women. This is also the visual method that the artist uses in her series Space of One’s Own (2012) that depicted Ukrainian single-sex couples in their rooms.[11] The descriptive, uninvolved approach that she assumes in documenting people in their living conditions intersects with a seeming disinterest in the technical side of the documentary process: the artist does not filter out the photographs’ noise, blurriness, and slightly unbalanced perspectives—pushing it closer to reportage photography.

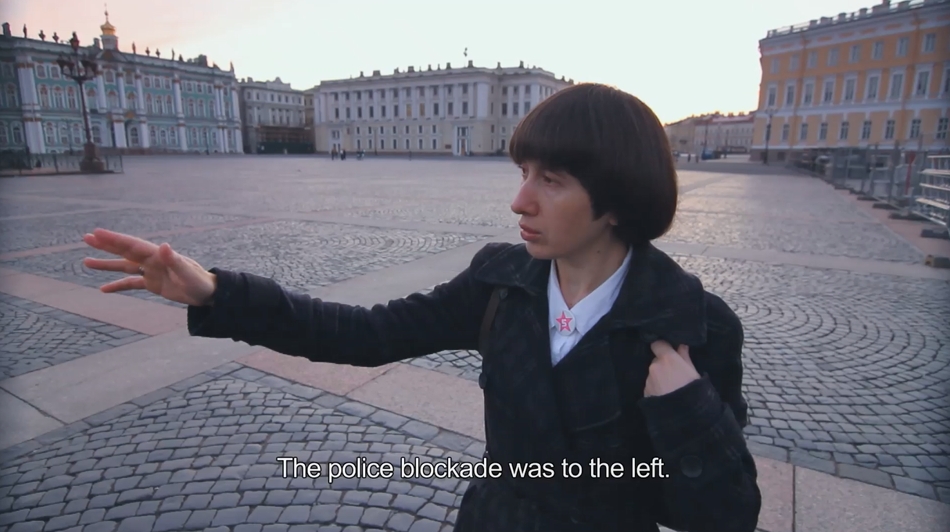

Kristina Norman’s Iron Arch (2015) in turn represents the political reality filtered through a double lens of witnesses and interpreters. The Estonian artist Kristina Norman filmed the Ukrainian artist Alevtina Kakhidze in the Palace Square of Saint Petersburg, where she performed a guided tour, pretending that the site of the square was Maidan in Kyiv where all the events of the protests took place back in 2014. In a rather subversive action, Kakhidze linked two geographical and political spaces: the square in front of Hermitage Museum and the central Square of Independence in the heart of Kyiv. Previously, the sculpture Souvenir (2015), made by Norman for Manifesta, was removed from the Palace Square because it was reminiscent of an unfinished fake Christmas tree— the symbol of the Maidan protests, which broke out in November 2013 and thus impeded festive preparations. At the same edition of the 2015 Manifesta, the artist Maria Kulikovska presented a performance 254. Action (2015) in which she laid on the steps of the Hermitage’s main entry wrapped in a Ukrainian flag, addressing Russian violence against Ukrainian soldiers, her own struggle as a refugee from the Crimea (registered under No. 254), and fear of making any mention of the situation in Ukraine among the Russian media.[12] The subversive dimension of these two artistic projects traced a new contour of Ukrainian-war-inspired protest art, where the former artistic collaborators became personas non grata in the Russian artistic establishment.

The breakthrough of Ukrainian documentary art relies on its profound engagement with problematic histories and the current crises related to the violence and the downturn in socio-political expectations over the last two years. In the long run, the documentary method will help to trace the social and cultural changes inside the country, as well as help to showcase a variety of perspectives to an amplified audience outside of it.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

The full text first appeared in the book Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art. Political and Social Perspectives, 1991–2021 (ed. Svitlana Biedarieva) published by Ibidem Verlag, 2021, as a part of Ukrainian Voices series. The book is available via the publishing house website.

[1] Mykola Ridnyi, “Foresight, Involvement and Helplessness: The Role of Culture in the Political Transformations in Ukraine.” In Svitlana Biedarieva and Hanna Deikun. (Eds.). At the Front Line: Ukrainian Art, 2013−2019, Mexico City: Editorial 17, 2020, p. 107.

[2] Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl, “Reconsidering the Documentary and Contemporary Art.” In Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl, (Eds.). The Greenroom: Reconsidering the Document and Contemporary Art, Berlin and Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Sternberg Press and Center for Curatorial Studies of Bard College, 2008, p. 12.

[3] See: Erika Balsom, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013); Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, eds., Documentary across Disciplines (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017); Okwui Enwezor, ed., Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art (Göttigen: Steidl, 2008); Maartje Van Den Heuvel and Hans Scholten, eds., Documentary Now!: Contemporary Strategies in Photography, Film, and the Visual Arts (Amsterdam: NAi Publishers, 2006).

[4] Olivier Lugon, “Documentary: Authority and Ambiguities,” in Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl (Eds.), The Greenroom: Reconsidering the Document and Contemporary Art, Berlin and Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Sternberg Press and Center for Curatorial Studies of Bard College, 2008, p. 35.

[5] Erika Balsom, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013, p. 18.

[6] That coincides with the aim of the recently-created Ukrainian Institute in Kyiv and other important initiatives, such as the ongoing discussion on formation of the contemporary art museum in Ukraine.

[7] For example, see: Panel discussion “Ukraine’s cultural Renaissance: How to keep it going?” Ukrainian Institute in London, 27 January 2021. Participants: Olesya Ostrovska-Lyuta and Marina Pesenti, moderated by Kateryna Botanova.

[8] Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, “Introduction. The Documentary Attitude,” in Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg (Eds.) Documentary across Disciplines, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017, p. 16.

[9] Svitlana Biedarieva and Hanna Deikun. (Eds.). At the Front Line: Ukrainian Art, 2013−2019, Mexico City: Editorial 17, 2020.

[10] Erika Balsom, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013, p. 15; 185.

[11] See in this volume: Jessica Zychowicz, “A new dawn at the centennial of suffragism: Artistic representation in transeuropean and transatlantic Kyiv,” 189-211.

[12] Maria Kulikovska, “254. Action,” available online at https://www.mariakulikovska.net/en/254-action. This project was not presented at the exhibition At the Front Line. Ukrainian Art, 2013-2019.

Imprint

| Author | Jessica Zychowicz, Margaret Tali, Kateryna Botanova, Ieva Astahovska, Svitlana Biedarieva, Olena Martynyuk, Vytautas Michelkevičius, Lina Michelkevičė |

| Artist | Mykola Ridnyi, Oleksiy Radynsky, Piotr Armianovski, Oksana Kazmina, Elias Parvulesco, Sashko Protiakh, Maria Stoianova, Kristina Norman, Olia Mykhailiuk, Yevgenia Belorusets, Alevtina Kakhidze, Maria Kulikovska |

| Title | Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art |

| Publisher | Ibidem Verlag |

| Website | www.ibidem.eu/ |

| Index | Alevtina Kakhidze Elias Parvulesco Kristina Norman Maria Stoianova Mykola Ridnyi Oksana Kazmina Oleksiy Radynsky Olia Mykhailiuk Piotr Armianovski Sashko Protiakh Svitlana Biedarieva Yevgenia Belorusets |