The Birth of Gypsy Dada: On the Life and Legacy of Damian Le Bas (1963-2017)

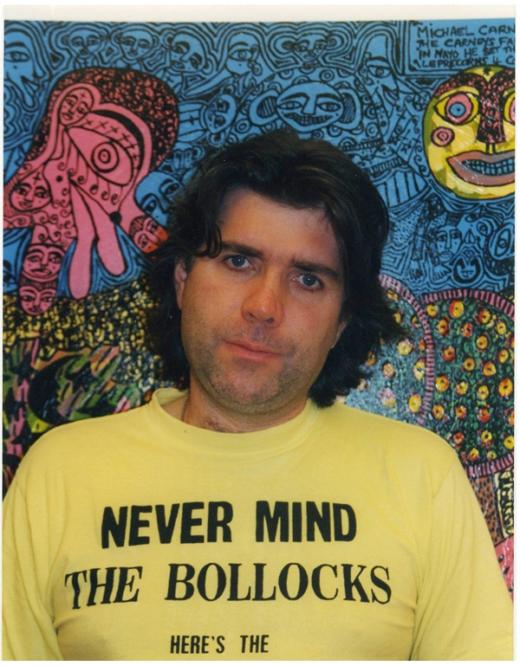

The artist Damian Le Bas, whose works are associated with the Art Brut and Outsider Art Movements, who once spent a month living with Roma people in a dilapidated shack just under a crown courthouse in York, recently passed away this past December at the age of 54. Carrying the legacy of the humble Irish Traveller, a boy who once sold flowers on the roadside, the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin is currently displaying a considerable collection of Le Bas’s works, including his set design for an ongoing play within their permanent repertoire, Roma Armee, a powerful political drama directed by Yael Ronen that impresses supranational, queer and feminist contexts of what it means to be Roma today, adorned with a stage exploding with Le Bas’s influence.

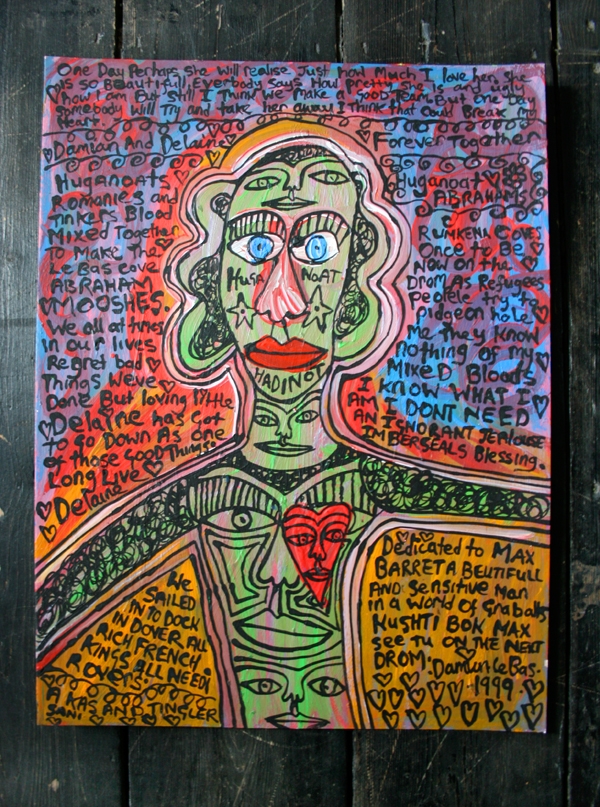

Le Bas’s work, perhaps above all else, paid humble tribute to the marginalized history of one of Europe’s most discriminated groups. “I’m literally putting Gypsies on the map,” Le Bas once said of his large-scale works depicting his community’s stories and symbols, challenging entrenched European stereotypes, hierarchies and bigotry in the process. Through collage and drawing, mainly, but also through the intimate perspective of being physically within Gypsy communities his entire life, Le Bas has extended the visibility of the Gypsy community far and wide.

Born in 1963 to a family of Irish Travellers, Le Bas was an embedded member of the European Roma community. In his work, he developed counter-narratives of Roma portraying them instead according to more positive, colloquial, universal visions of Roma in the wider world.

‘Gypsies,’ Le Bas’s preferred term for the people who descended from Sinti tribes in Central Europe that share a common South Asian ancestry, have largely found it difficult to assimilate since they arrived in Europe some seven centuries ago.

As a neglected and marginalized transnational community of people without a fixed land or nation, Roma nevertheless share two essential requirements of a country: a linguistic and cultural heritage. Closely descendent to Sanskrit and Hindi, historians typically believe (but do not always agree) that Roma began establishing themselves in large numbers throughout the Balkans by the early fourteenth century, later spreading to England, France, and Spain, by the early 1500s. Yet, like any group coming to a territory anew, they came with different sets of traditions and values, languages and customs, ones that made it difficult for them assimilate into the class system of Medieval and Early Modern Europe.

Whether at the behest of monarchs, communist politburos, social democratic parliaments, or fascist despots, integration has been difficult for the vast majority of Roma who routinely face criminalization over their nomadic lifestyle, racistly cast into a class of European untouchables. A 1991 Times Mirror survey found that Europeans in overwhelming numbers expressed contempt for Roma: 59% of Germans, 91% of Czechoslovaks, 71% of Bulgarians, 79% of Hungarians, and 50% of Spaniards, the study found. In the 1970s, moreover, Czechoslovakia even enforced drastic measures to stem Roma population through government-sponsored sterilization efforts, a policy later mimicked by the Norwegian government in the 2000s. As recently as 2017, in a complete twist of hate seemingly boomeranged in from the 1970s, the recently re-elected president of Czech Republic, Miloš Zeman, provocatively claimed in a television interview that 90% of his country’s “unadaptable” citizens are “probably Roma.”

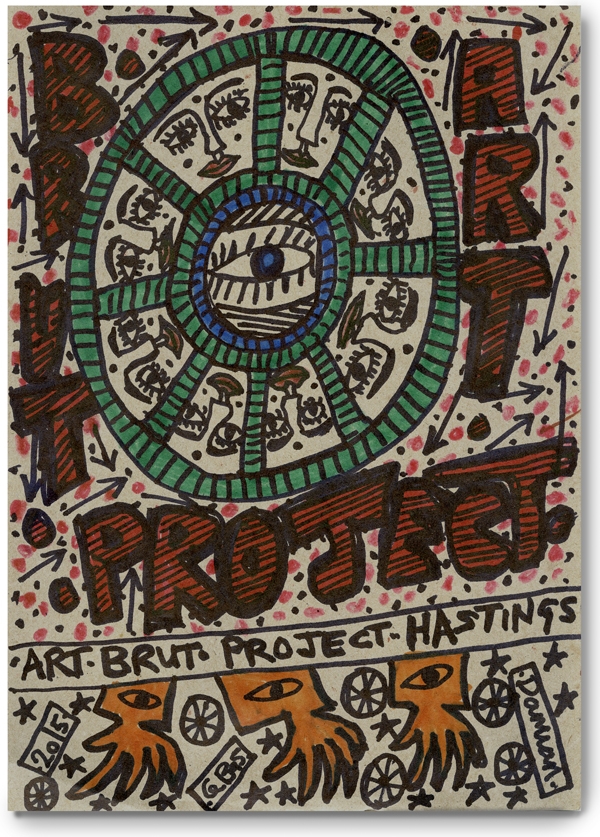

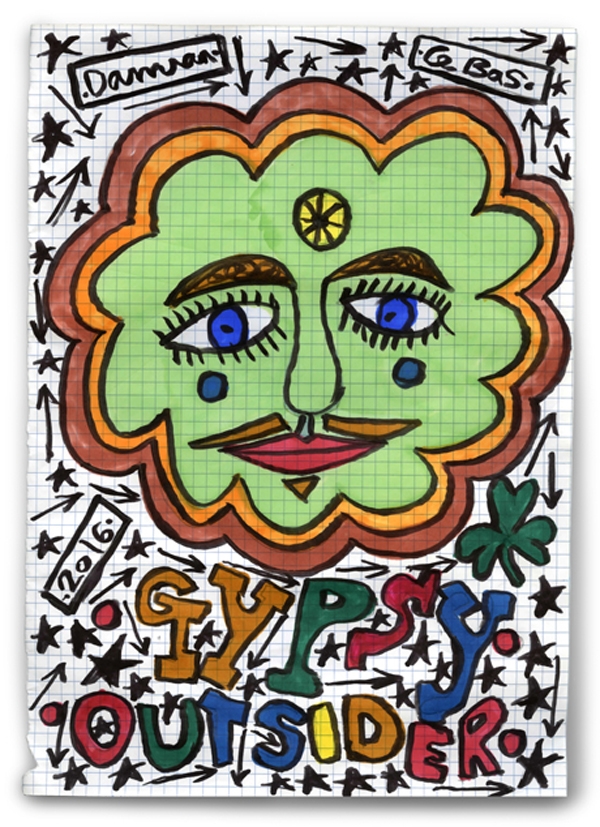

Throughout his life, Le Bas tried to re-fashion images of Roma people in an affirming light, sauntering his work with positive, rather than depressing, images. Frequent motifs consisted of flowers, textured eyes, wheels, erased borders and nations, people, sometimes adorning objects like globes into gallivanting groups of smiling Gypsies on the move. His work later evolved into installations and larger-scale projects that would roam wherever he went.

In 2007, for example, Le Bas helped organize and participated in the first Roma Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, curated by Timea Junghaus, the first edition of a performance and platform dedicated to giving voice to Roma art. Two years later in 2009, an intervention hosted by 10 national pavilions in Venice by the curatorial group Perpetuum Mobile (PM) (co-founded by Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolosky), developed another edition of a meandering Pavilion in Venice.

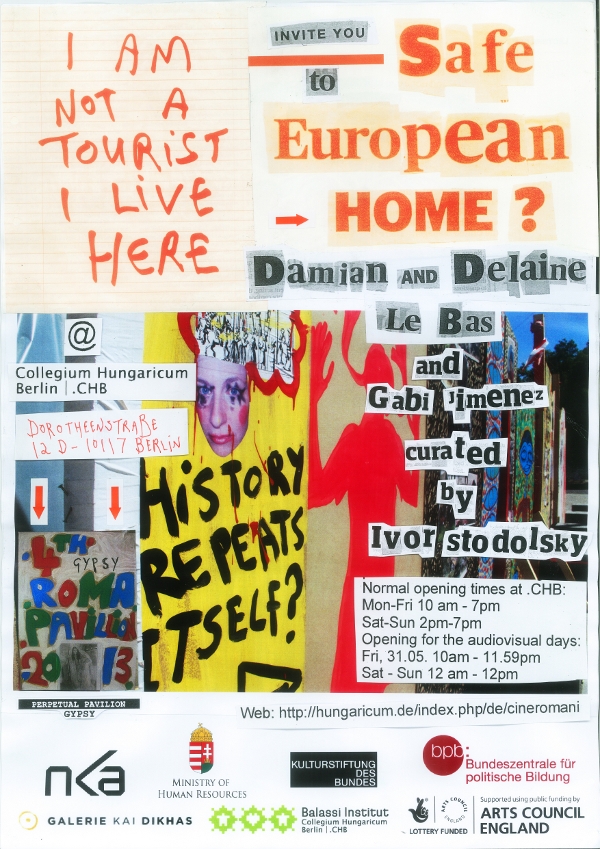

On the occasion of what would have been the 4th Venice Pavilion in 2013, Le Bas found himself in Berlin, invited by PM, to install a small shanty-town-like house for a project called Safe European Home? (2011), which also featured contributions from Gabi Jiminez and other artists and activists. Conceived as an outdoor public walk-in installation, “We suddenly realized that this day was the opening day of the Venice Biennale,” Stodolsky of PM said. “Damian just stood there, brush in hand. Once again, Roma art was not represented, forgotten, not visible. But suddenly, in a form of a Dada act – whose aesthetics he was very close, too – he took the brush and painted ‘4th Roma Pavilion’ on the side of the shanty standing forlorn in front of the arch-modernist building of the Hungaricum and across from the venerated Gorki Theater. In an act of what we were already calling ‘Gypsy Dada’ – a ready-made Venice Pavilion was created. A nomadic pavilion to be sure, but forced nomadism is precisely what so many Roma have to experience to this day,” Stodolsky described.

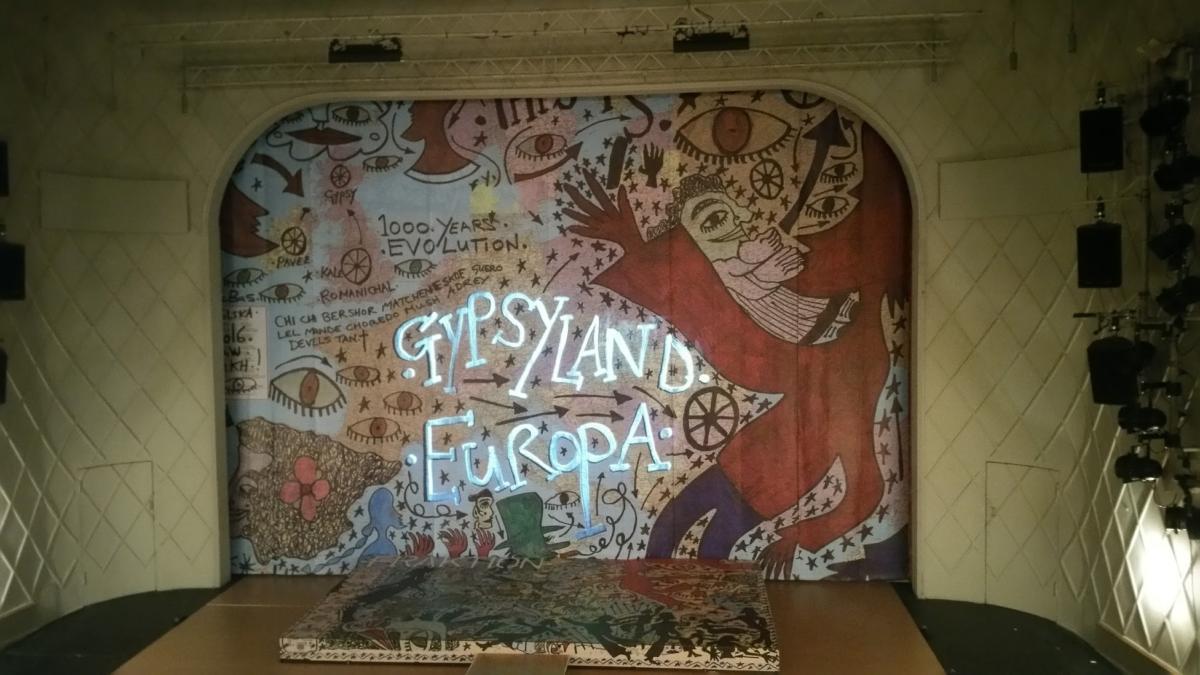

The turn in the artist’s work from small-scale cartography to mobile-based installations and large-scale set design came naturally. When Maxim Gorki Theater, a multi-disciplinary theater in Berlin that focuses on immigration, race, and assimilation asked Le Bas to join, it turned out to be a match made in a caravan, in a way, perfect. Led by the Gorki’s bold and fearless director Shermin Langhoff, Le Bas and Delaine soon began work on what would eventually become Roma Armee. For the set, Le Bas and Delaine developed a moveable illustrated appartus that actors eventually knockdown in an act of defiance in their struggle to realize a fictional Gypsy state, a massively powerful political drama in which the actors eventually transform the stage and Le Bas’s set into military barricades for a showdown against the inveterate oppressive enemy, Europe itself. For the curtain, Le Bas created an enormous and intricate map of Europe complete with one of his classic motifs, a leering straight nosed figure ominously gesturing towards the continent, while underneath the words “Gypsyland Europa” are projected in light.

Also together with his wife Delaine, the two last year re-designed a fence in front of the Gorki, painting it over with maps and historical photographs of them as a couple. The choice of re-designing a fence offered a dish of potent symbolism: Far from being neutral objects, fences represent the idea of ‘Fortress Europe,’ connotations populists often use to argue for a migrant and therefore Gypsy free Europe, ideas which Le Bas spent his life working vehemently against. Of Romani History X., he said, “We claim this space for ourselves. We who are framed, limited and defined by those who want to control, name and silence us. Here we are,” welcome to Le Bas’s Gypsyland Europa.

Le Bas’s work perhaps embodies what political philosopher and art theorist Gerald Raunig refers to as “theater machines,” a merging of art and activism. With the rising specter of populism, on a visceral level, Le Bas seemed to summon the “nomadism” of his Gypsy roots as a way of formulating a soft resistance to dominant state power. Thusly establishing precisely would Raunig would describe as “nomadic existence, fleeing, deserting the state apparatus,” forming a new type of “sociality, instituent practices and constituent power, the creation and actualization of other, different possible worlds.”

And herein rests the underlying political consciousness left behind in Le Bas’s work: forming, it would seem, art in the image of a new Gypsy Dada, capable of shape-shifting into assemblages of politically defiant, non-conforming theater.

Damian Le Bas, 1963-2017.

Rest in power, Damian.

Damian Le Bas’s work continues as part of “Roma Armee” at the Maxim Gorki Theater (Am Festungsgraben 2, 10117 Berlin), various dates and times.