Lesia Kulchynska is a Kyiv-based curator and visual studies researcher. She worked as a curator at the Visual Culture Research Center, Set Independent Art Space, on projects Ukrainian Body, Some Say You Can Find Happiness There, The School of the Lonesome at The School of Kyiv, Kyiv Biennial, The Raft CrimeA, Somewhere Out There Somewhere Beside, Art= Capital?, Public Self-Reflection Program at Kyiv Art Fair, The Reason Of Disappearance. She is the founder of the Mobile School of Visual Education, Service project and talk show Sincerely about art and the author of Meaning Production in Cinema: Genre Mechanisms. Kulchynska is an Art History postdoctoral fellow at Biblioteka Harteziana Max Planck Institute.

We wanted to talk with Lesia about Sweet Dreams Foundation – the exhibition she recently curated in Nida, Lithuania. We also spoke about her earlier work and how her curatorial practice has changed since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The interview was conducted in October 2022.

Yana Ustymenko: The works shown as a part of Sweet Dreams Foundation share the themes of uncertainty, privilege, safety, and temporality. How and at which point did you unite them under the umbrella of dreams?

Lesia Kulchynska: This is the result of self-observation, the experiences of my friends and other people I’ve met. I remember reading several posts on Facebook by some of my friends who said they felt nervous whenever they tried to plan something. At the beginning of the year, we usually have plans for the following year – we are going to do this, and this, and that… And then, at one moment, all your plans just disappear. You continue experiencing how everything unpredictably changes every day, and you just lose the ability to think strategically. Because to think strategically, you need to have a certain ground to make these calculations. During war this is just not possible; you don’t have the needed information to predict anything. Somehow you have to exist in this situation of fundamental temporality. Even now, I’m in a place where my future is defined just for a few more months, and then I have only an idea of where to move further. The future has become inaccessible. And in this situation, I thought that since you cannot calculate anything, since you cannot plan anything, the only bridge to the future is through dreams. And these dreams can be unbounded from any rational thinking. You have no idea of what’s going to happen tomorrow, so you have no limitations. Dreaming then becomes this practice of creating the future out of nothing. So that was my idea – since we lost a perspective of the future, we get a chance to create it completely differently.

“When reality is falling apart, dreamers might perceive their own special mission,” you wrote. What shared dreams did you discover in the process of working on this exhibition?

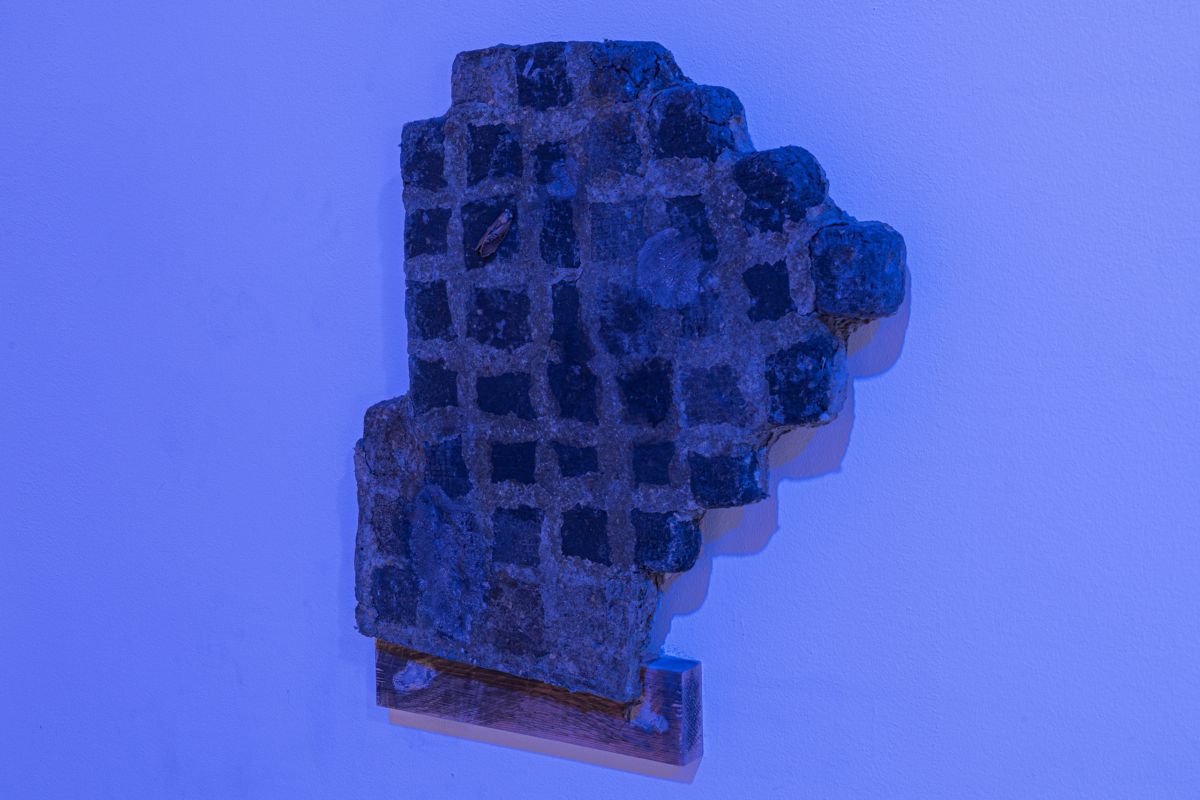

Most of the works presented in the exhibition were produced out of waste material. Artists managed to create something beautiful and very touching out of these discarded materials. I had this feeling that maybe this shared dream was about the possibility of a second chance, a possibility for an afterlife. An idea that whatever has been destroyed or smashed can still be transformed into something beautiful and warm, something alive. That’s what I personally encountered in this exhibition as a viewer, not even as a curator.

Another observation I noticed was this desire to be connected with the space where we were at the moment, discovering what was around us and building reality from it. If you start exploring it, you discover a huge amount of possibilities previously neglected. Because when you lose something, your first reaction is – everything has been lost. But when you start connecting to the place where you are at the moment, you start discovering treasures around you, unobvious possibilities that can serve as a building material for the world.

Some works were developed on-site, such as The Guardian Angel by Kseniia Scherbakova or The Place of the Unknown by Nataliia Kushnir. Others were produced a few years before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, such as the documentary film Diorama by Zoya Laktionova. Did you find it challenging to merge them?

Actually, it’s not a different reality. The film Diorama you mentioned is about the city of Mariupol and its inhabitants. At the time when the film was produced, the city was already much closer to the war than most of us at that time. The film tells the story of existence near the frontline, living in close proximity to war. You hear inhabitants talking about the mines in the sea, how the landscape and the city have changed, how the ecological situation has changed as a result of the war and the industrial economy. But still, regardless of this proximity to war, people try to live there. They are very much connected to this place. They believe they can still live there regardless of the traces of the approaching catastrophe. And when you watch this film now, knowing what has happened with Mariupol, you see something that no longer exists. The life this film portrays is not possible anymore. When you watch this film now, you can already see the future of what will happen there. And you can feel the extreme fragility of the depicted reality. The film was actually one of the main inspirations for the show, especially since I first watched it during one of the massive shellings of Mariupol.

For me, this film also became a metaphor for thinking about the world in general, that we live in a world which is very much in danger. And we can see traces of this danger even if we are in a safe space somewhere outside of Ukraine. In this sense, the film became an invitation to think about the vulnerability of the world. That’s why the reality shown in the film is not something different from what we experience today. Although it was filmed before the full-scale invasion, it still gives you this perspective of the upcoming future. Whenever I watch this film, I get a feeling that I am looking at my own life but from the future.

The subject of war is not new in your work; Between Revolution and War (2014), The Raft CrimeA (2016), Somewhere Out There, Somewhere Beside. Ukrainian Video Art 2015–2019 are just a few examples. How did your work process change since February 24, 2022?

Thank you for the question. Yes, indeed, the work process has changed since February 24. The war started in 2014, and at that time it seemed to me that the main problem was that the war was somehow ignored, even for those of us living in Kyiv. There was a feeling that the war was close, but it was still somewhere “out there.” So the projects I did at that period of time, and specifically the exhibition I made at the Nida Art Colony – Somewhere Out There, Somewhere Beside, was an attempt to remind the world about what was happening. I wanted to bring it to attention. To remind people that it wasn’t as far as it seemed. You might not feel it, but it affects us in different ways, maybe even unconsciously, but it definitely influences our reality.

When the full-scale invasion happened, you no longer needed any reminders. It was very intense. The presence of war was everywhere. At first, the very idea of making exhibitions about the war seemed rather redundant to me. What’s the reason to make an exhibition when reality is so much stronger and it needs your action, not reflection?

With the first exhibition, State of Emergence, opened at Catinca Tabacaru Gallery, this need for expression came from working on my own feelings of anxiety and despair. The exhibition was in Bucharest, where I fled from Kyiv after the full-scale invasion. The presence of war was very much there – all the talks were about the war, you could feel a sense of fear very strongly, even among people from Romania. I was very overwhelmed by the feeling of the collapse of a familiar reality, but at the same time, I noticed that this situation of collapse, paradoxically, has a huge creative power in it, because when everything is falling apart, you have to build your reality anew again and again, and you can build it differently. Something new emerges in the place of what has been destroyed. So with State of Emergence, I tried to focus not on the destruction but on the things that were emerging from this collapse. I tried to refocus my attention from death to life.

So, yes, earlier I wanted to talk about the war that was happening, but we ignored it. Now, when the war is already so present everywhere, I am trying to transform this feeling of being helpless and overpowered, the feeling of being in danger, into something else. With my work after February 24, I try to grasp the ground from where I can start to move forward. The approach actually became quite the opposite, right?

By the way, the second edition of State of Emergence took place in Sandwich Gallery in Bucharest, run by artist Daniela Palimariu, who later became one of the participants of Sweet Dreams Foundation.

I can definitely relate to the feelings you have described. In 2019, you came to Nida as a participant in the NAC residency program. This time you visited Nida under very different circumstances. What was your experience of working here compared to your first memories of this place?

When I received the invitation to create Sweet Dreams Foundation, my previous experience of staying in Nida was very influential for how I started thinking about this project. I imagined it to be site-specific, linked to this place. What I remembered from the residency program in 2019 was the feeling of safety. When you come to Nida, all problems feel far away. This place is just so peaceful. It’s so serene. You have the sea and the woods around. You can somehow get lost there yet still feel protected. I thought that for people who live in Ukraine, for the artists who live in this dangerous reality, it’s important to be able to escape at least for a while, to have a chance to think not only about their survival but to reflect on their experience, to think and even to dream. During the first months of the escalation of the war, most people, including myself, were only worried about surviving. Even those who were not in Ukraine were surviving emotionally as they were observing the violence which has become an everyday reality. It was easy to slip into despair and depression. I thought it was important for Ukrainian artists to be able to come to a safe space, to have a break to breathe freely and open up their thoughts and imaginations to the possibility of thinking about the future. We couldn’t predict it, but we at least could dream about it.

But when I came to Nida to prepare the exhibition the context was different. Around three weeks before the opening – I wasn’t yet in Lithuania at that time – there was a lot of information about possible provocation at the border between Lithuania and Russia. And Nida is about a forty-minute walk or so away from the border. There was some news about movements in Kaliningrad that even my mom called me from Ukraine and asked me not to go there. So it was completely different. This feeling of safety was lost. When I eventually arrived in Nida, together with the artists who had been staying there in the residency program, we decided to walk towards the Russian border. One of the artists, Dasha Chechushkova, wanted to film a short video there. The idea behind the work was to create ghost guardians who would stay at the border to protect us. But eventually, we didn’t manage to get all the way to the border. At some point, all of us started feeling very anxious and we made a decision to go back. It was such a relief.

That’s the change of perception. This time I didn’t feel that safe in Nida, especially since I was also there with my child. But I think for artists who came from Ukraine, it still functioned as this possibility to take a break from the war.

I recently watched a panel discussion where you spoke on how war shapes Ukrainian art and decoloniality. There was one phrase you said that particularly stood out to me and also resonated with the Sweet Dreams Foundation exhibition. “Emergence might be a flip side of the collapse, of the emergency.” Could you elaborate on this thought in more detail?

I started looking into the relationship between the words emergence and emergency a while ago, probably after the invasion of Donbas in 2014. However, at that time, it was more like a theoretical revelation for me. I discovered that these two words were indeed quite similar and wanted to explore the connection more in-depth. But my approach was rather analytical.

After the full-scale invasion, I literally felt this connection with my skin. When we left Ukraine, I had a feeling of heading into nowhere. The place in Bucharest where we stopped was a temporary possibility for us. We had no idea where to move next. At that period of my life, it was even difficult for me to talk. I couldn’t communicate properly, even with my closest people. You don’t know what to say in this situation; everyone is extremely vulnerable, and you sometimes feel scared to ask questions like “How are you?” not to trigger something that could have happened. It was a period of total puzzlement. I didn’t know how to move. But regardless of this collapse we’re living through, life still goes on. At some point I realized that you inevitably start reinventing yourself. You reinvent how you communicate with people. You reinvent your daily life because your routine has been lost. You need to reinvent everything at every level. In the process of this self-discovery, I once again got back to the idea of emergence. When everything is being destroyed, you are forced to create a new reality from scratch.

Also, I was observing what was going on in Ukraine, noticing all the amazing things that started to happen alongside destruction: this incredible solidarity, mutual support, help and care. While our familiar paths are being destroyed, we are reinventing everything anew. It’s very precious to think about it – not about what we are losing but what we create every day amid this intense violence. It seemed to me that maybe this is something worth focusing on, you know. It gave me some hope.

Sweet Dreams Foundation includes the works of artists from Ukraine, Lithuania, Romania, and Switzerland. I understand the selection of participants traces your route from Ukraine through Romania all the way to Rome, where at Istituto Svizzero di Roma you met artists Marta Margnetti and Giada Olivotto. You also knew Ukrainian artists who had lost their artists’ community house in Odesa and, knowing NAC, imagined them similarly working in Nida yet under different circumstances. How did different backgrounds, experiences, and visions come together in this exhibition?

When I first started thinking about the exhibition, I was going to invite only Ukrainian artists. But then, when I fled from Ukraine to Europe at the beginning of the war, I met many people with very similar backgrounds. You might be standing in line in the shop when somebody asks about where you come from. In the conversation, you find out that this person is from Pakistan or from Libya and that they also lost their home. Plenty of these stories. I feel that war is a part of modernity, it’s a part of the world we live in. The wars were there before, and they will be there after. It’s something that many people throughout the world are living through every day.

What also influenced my decision to include international artists was meeting Marta Margnetti and Giada Olivotto. I went to their studio for a visit, where they told me about their project Fattucchiere (also the name of the duo that they work under), and Prêtes-à-pleurer (Ready to Cry), an idea they had been developing at that time, that we decided to include in Sweet Dreams Foundation. Marta and Giada were thinking about creating a space where people could gather to share their predictions about the future. They wanted to give these conversations a positive light, encouraging people not to think about catastrophes but imagining a different future. Something that we would like to have. It’s a practice of imagining the future and hoping that such conversations will contribute to it.

I learned that Marta worked very closely with the experience of rootlessness, of not having a home. That’s one of the major themes she explores in her work, and it very much resonated with the idea for the exhibition that I had in mind. I also realized that this experience I was living through is comprehensible not only by people who had a similar experience of living through war but by anyone dealing with a similar existential situation: be it losing a close person you loved, or the life that one used to have, living through transition and uncertainty. That’s how I came to the idea that maybe it would be interesting to speak about this experience not only with Ukrainian artists but also invite artists whose practices resonated with my experiences and feelings.

And, not to forget that we are citizens of the same world. This war that is happening is not only about Ukraine and Russia, it’s something much more universal. I think it’s worth sharing our experiences and discussing them with others.

I feel that you also encourage this discussion by inviting the audience to participate actively in the exhibition. I am thinking about the masks created by Yana Bachynska, who suggests people try them on. Or Mila Kostianá, who created a space for the visitors to leave their own abstract needlework on one shared piece. Or Daniela Palimariu, who invites visitors to literally stretch and work on their flexibility. What is the role of the audience in this exhibition?

Yes! Actually, the idea was to make this exhibition a kind of inhabited space – you are invited to come and stay with other visitors for a while but also with the stories and creatures who already exist in that space. It was interesting to me to create a space for being together. You see all these faces, figures, different creatures and spaces where it feels like somebody used to live there but then disappeared. It’s a place where you can stay for a while. I had the intention to create this environment that would function as a temporary shelter, which I was maybe also looking for at that moment.

The visitors would embroider and read the zine. You can even talk to those voices that are present in the exhibition, or maybe just speak to yourself. I tried to create a space where you could have the experience of being with something unfamiliar – of staying with those unfamiliar and strange creatures you see and maybe trying to establish your own relationships with them.

The theme of temporality feels central to Sweet Dreams Foundation. The painting The Charm by Borys Kashapov has slightly changed its appearance under the heavy Lithuanian autumn rain, and the giant dress crafted by Dasha Chechushkova is not the exact same shape or color after three months of hanging in the woods (it feels like it has established its own roots and has melded with the ground). The exhibition itself is also temporary. What impact did working in/with this transitory state, as you described it, have on you personally?

That’s right, and I was also trying to deal with the temporary nature of the exhibition as a medium. Any exhibition is temporary, but it requires much effort and very often consumes a lot of materials. And when this temporary exhibition is over, we are usually left with a lot of waste. The art field always tries to speak up on ethical issues, yet in the way that it operates, it actually tends to produce a lot of waste and damage to the environment. With Sweet Dreams Foundation, we tried to make it the other way. Many works included in the exhibition were produced to stay in Nida, and they will also have their function after the show. For example, The Stretching Room by Daniela Palimariu, which people coming to Nida will continue to be able to use, or the wooden bookshelf by Fattucchiere that will stay in the NAC library.

Understanding the temporal nature of the exhibition also inspired many artists to work with the materials that were available on-site. In fact, most of the works were produced out of waste material. We collaborated with Neringa’s recycling and waste station, where artists did research and figured out what materials they could use. Giving new life to something that had already been wasted so the works could either continue functioning and serving people or they could easily be dissolved, as temporary objects.

It was our reflection on this special mode of existing in this temporary reality, when you cannot build your life on solid ground, yet you still need to somehow furnish your reality. It’s the way of working with what is on hand. Perhaps it’s worth thinking about not only in the context of lives that have been impacted by war but also about the situation on this planet, which is also in danger. It’s an attempt to introduce a way of life that would be more connected to the environment and the possibilities that it provides you with.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

___________________________________________________________________________________

Yana Ustymenko completed her BA in Contemporary Communication from LCC International University. During her studies, she was an intern and later worked at Nida Art Colony, Lithuania (2020-2021). In 2022 she completed a course in Art Curation followed by practical training at TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art, Poland, and became a participant of the De Structura project, Estonia — a multidimensional initiative for young artists and cultural professionals. Since 2021 she has been working for the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, Ukraine, exploring her interest in questions surrounding national identity, collective memory, and ideologies.

Imprint

| Artist | Yana Bachynska, Dasha Chechushkova, Fattucchiere (Marta Margnetti and Giada Olivotto), Agnė Juodvalkytė, Borys Kashapov, Mila Kostiana, Natasha Kushnir, Zoya Laktionova, Marta Margnetti, Daniela Palimariu, Christian Raduta, Kseniia Shcherbakova, Anna Sorokovaya. |

| Exhibition | Sweet Dreams Foundation |

| Place / venue | NIDA Art Colony |

| Dates | 16.07 – 16.10.2022 |

| Curated by | Lesia Kulchynska |

| Index | Lesia Kulchynska Nida Art Colony Yana Ustymenko |