Vera Zalutskaya: Is it a coincidence that you’ve recently curated two shows of Polish Jewish artists: Erna Rosenstein. Once Upon a Time at Hauser & Wirth, New York, and My Name is Maryan at the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami?

Alison Gingeras: The coincidence of the shows being back to back is rooted in the scheduling changes caused by the pandemic. Otherwise it is not a coincidence in the sense that I have had an interest in post-war Polish art for the last 20 years, since I started going to Poland and living there part time. When it came to Erna Rosenstein, I was just really blown away when I came across the book I Can Repeat Only Unconsciously that was published by Dorota Jarecka and Barbara Piwowarska, the first serious monograph on her work. At first, I couldn’t compute: who was this artist, which didn’t fit neatly into one category or movement? I decided to do my own research, so I worked on that for many years before even being able to find a place in the US to do the show. To me, Erna defied a lot of preconceived ideas about post-war Poland. In the States, there are so many prejudicial understandings of history. There are assumptions that all Jewish people were eradicated and that there was no continuity of Jewish life after the war, which is not true. So it was absolutely compelling to create this book and exhibition that would allow for a non-Polish person to really get into the weeds of the history and its complexity, because in a way, to tell Erna’s story is to tell the history of post-war Poland.

V: And how was it in Maryan’s case? Do you see any similarities in their lives and practices?

With Maryan it was different. I was approached by the museum in Miami to investigate his history, and see if it was a viable exhibition because very little was published or documented about him. It is interesting to follow how Erna and Maryan kind of inverse each other’s stories, they have different experiences and traumas. First of all, they came from two very different backgrounds. Of course, they were both Polish and Jewish. Yet Erna was from an upper-class assimilated family, she grew up between Lviv, Krakow, and Vienna–she was part of the post-Habsburgian intelligentsia. Maryan was from a working-class family in a small town called Nowy Sącz. While Erna was never imprisoned in a Nazi camp, she survived genocide and bore witness to unspeakable acts. Erna really held her ideological belief in a kind of utopian communism and those politics very much drove her life choices before the war, but her aesthetic language ran counter to official culture after the war, and despite this, she persisted in making her work.

Maryan, Personnage, 1962, Oil on canvas 50 x 50 in. (127 x 127 cm) , Collection of Anne Wachsmann Guigon

Maryan on the other hand just had to survive. He had nothing at the end of the war. He didn’t have a circle of friends or other artists to rely upon after the war. He was much younger than Erna, he was only 12 when he was first imprisoned, and spent his entire adolescence in camps, ultimately arriving in Auschwitz. Erna had already been through art school, she had been in Paris to see the First International Surrealist exhibition. Maryan was a refugee who arrived in Jerusalem with his papers stamped “handicapped”, he wasn’t allowed to study art as he was originally promised. He had so many struggles–during and after the war–so he reinvented himself with a new name that was freed from the association of his Nazi imprisonment. The difference in their names is also interesting. Erna hid under numerous Christian names during the war and then after the war, she signed her real name on every painting, re-encoding her identity on the front of each composition. Maryan decided that he didn’t want to live under the name that he was imprisoned under, and reinvented himself when he left Israel and arrived in Paris to study at the Beaux-Arts in 1950. He took this name “Maryan” because it was a very common male name in Polish. I think it’s interesting that for both of them, naming became so important to their assertion of their selves and their identities after genocide.

Maryan’s story is, so to speak, more classic: he ultimately left Poland, immigrating first to Israel, then to France, and then finally to New York. But there was also this atypical side that really appealed to me. He became an American citizen in the 60s and was associated with an eccentric group of artists, but he was never part of a movement. And to me again, to tell the full complexity of his story and his relationship to his birthplace was really important. He also fell outside of the master narrative of postwar art.

I was very interested in how these two artists in the 1940s were amongst the very first artist-witnesses to create representations of their experience of the Shoah. And there’s even a very incredible formal similarity between Erna’s works, like the painting she made in the late 1940s of a deportation train where the figures are made with a heavy black outline; Maryan was making similar works in Israel in 1947 and 1949 with the same type of outline and cartoonish figuration. One can almost see their common struggle to represent these horrific experiences, and the drive to share them and to immortalize them through their art practices. Neither of them stayed in that mode of painting after the late 1940s. Erna’s imagery became this kind of surrealism, for lack of a better term, and the kind of dream logic that is present in her paintings is more ambiguous while Maryan uses a very quirky expressionist figuration. There’s no mythology or enchantment in his works. They generated two very, very different energies.

V: Did Maryan ever come back to Poland?

A: No. I was interested in digging deeper than whatever had been published on Maryan, and tried to uncover more about his relationship to his Polish identity, and how that played out in his work. I did a lot of interviews with people who knew him and it was interesting to learn that, for example, in New York, he did speak Polish if he met a Polish person. I think that’s kind of interesting evidence that he did not completely repress his Polishness, that it obviously was part of his self-definition after the war. And I also found works of his that were never exhibited. He basically took replicas of the medieval wooden faces from Wawel Castle and overpainted and modified them so that they kind of looked like his paintings, which I also think is somehow significant. And he also had this rocking horse that he was obsessed with, which he brought from Poland and kept in his studio. He wrote about it in the text published right before his death, that it was a really important part of his childhood because he never had one. He so wanted a wooden horse yet because his family wasn’t wealthy, it was denied him.

V: How does he work with his memories in his art?

A: The most important and explicit dealing with this issue of memory is in the notebooks that he made between 1970 and 1971, where he’s starting to go through an incredible psychological turbulence. The trauma of the war has caught up with him and he is under the care of a psychiatrist; unable to speak, this psychiatrist instructs him to make drawings to try and articulate what he can’t say. He made over 500 drawings. He captions these drawings with his own writings and they don’t just explain what happened to him in the camp. They also go back to the happier and the more identity-forming moments of his life. So he talks about his mother and his father, Purim, and his village. He talks about his father’s bakery and the bagels and the pretzels he made. So all of this sort of imagery that is not explained in the paintings are explained in these drawings. So all of these things put together weave a certain narrative of his life. But I think that it is important to bring Maryan back into dialogue with other Polish post-war artists–and specifically other Polish-Jewish modernists– because he is this missing, ghost-like figure.

V: Could you name a few main themes in his art?

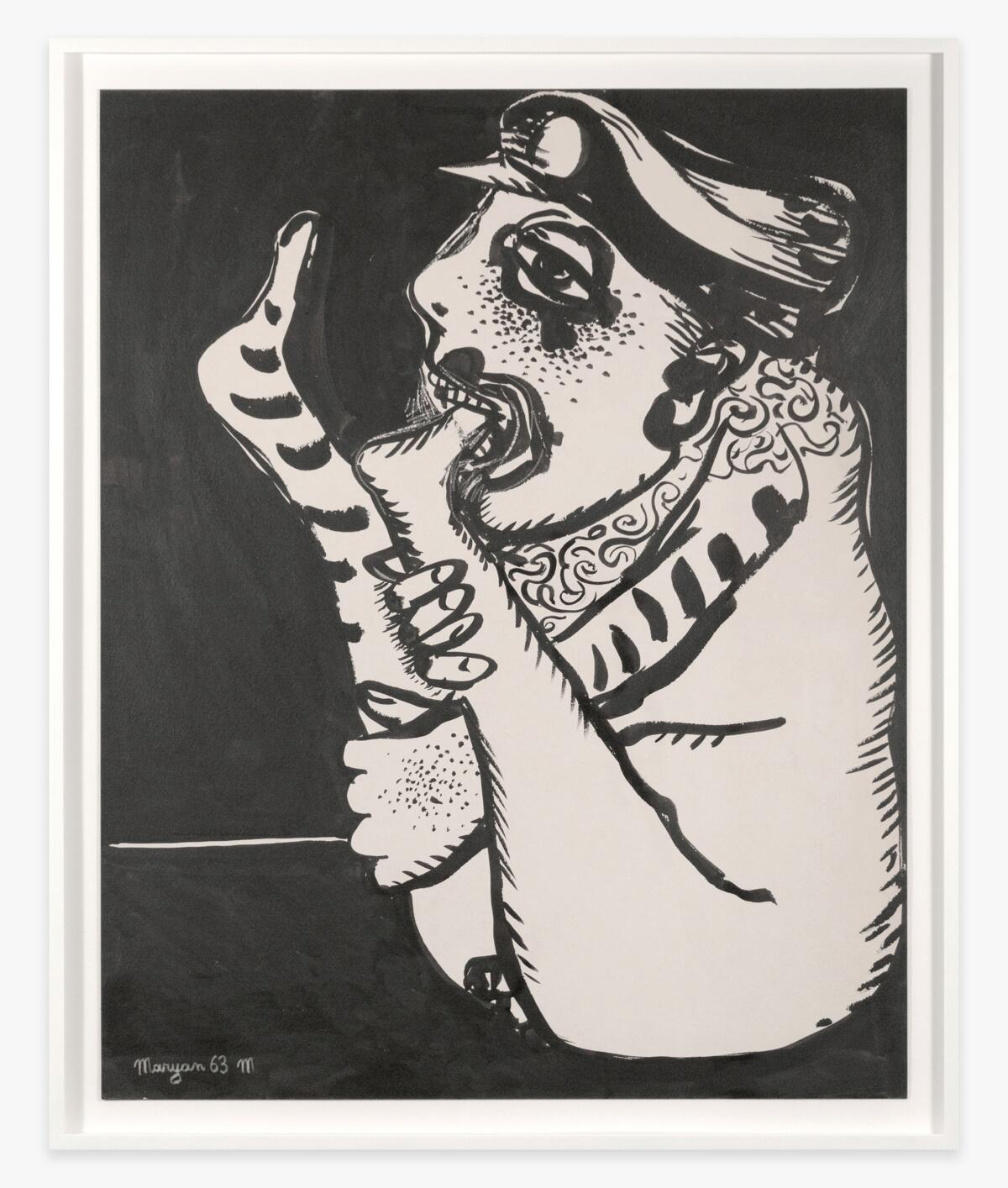

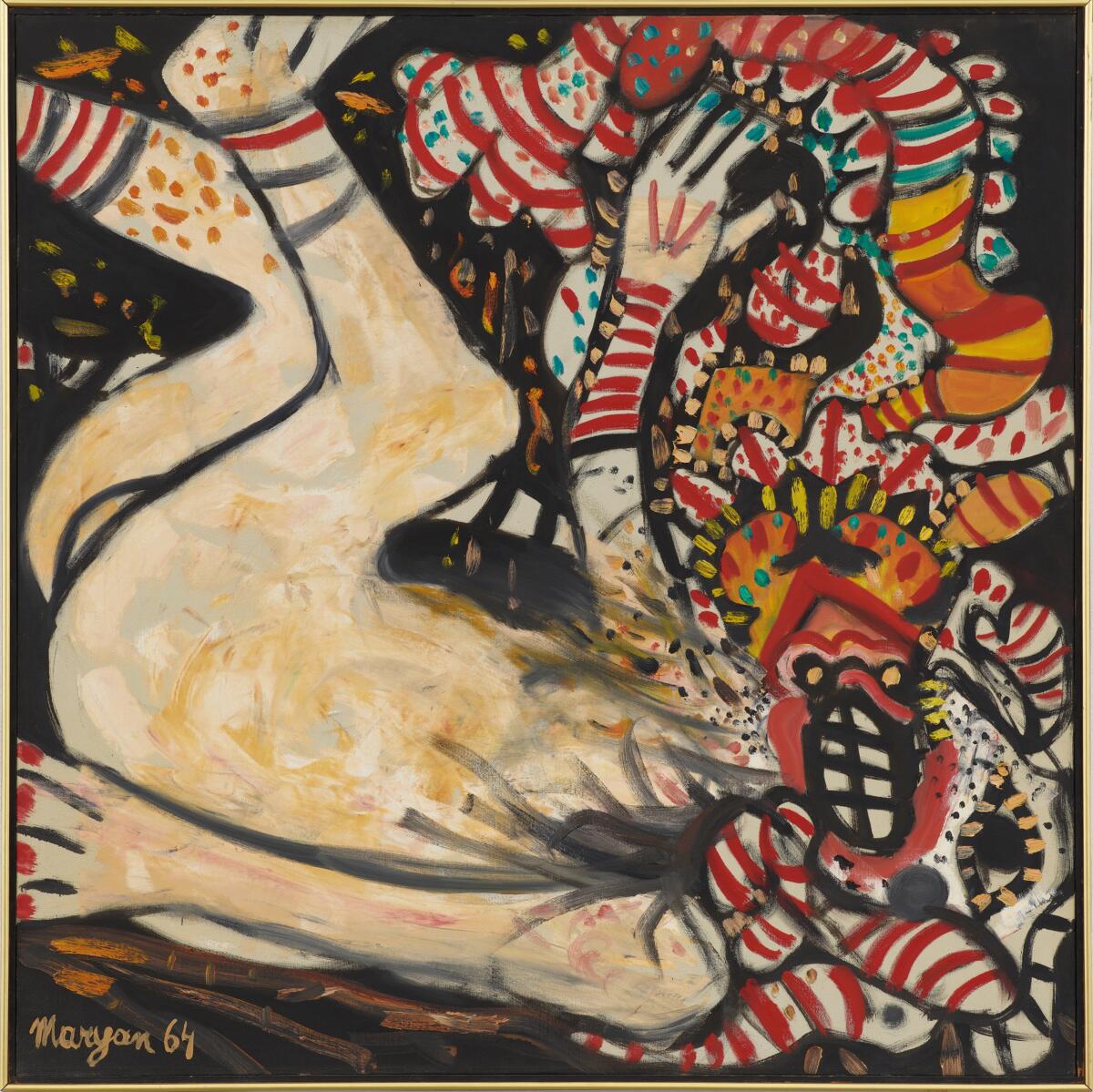

A: Maryan is constantly asking this question: how, after experiencing the most dehumanizing treatment imaginable, could one conceive of what it means to be human? His key theme was the personage or the character. All of his fictional “personages”, or characters that he paints, are constantly decomposing and recomposing in his work are his processing of that very question. And it’s almost always a head. Most of the time, his figures have no body. There are representations of Napoleon where he deconstructs the figure and displays his body open, showing his organs, his head exploding, with things coming out of his mouth. He looked a lot at art history and also worked in series, one of which was after Goya. He also made this film called Ecce Homo which is a Holocaust testimony where he’s speaking to the camera and dramatizing the scenario, but then he’s also intercutting the film in an experimental way with images of sociopolitical events like anti-Vietnam War protests, civil rights riots, and Ku Klux Klan gatherings. It’s an interesting moment where he’s trying to connect his trauma and his survival to the things that were happening at that time in the world. He termed this work “an anti-genocide work of art.” This is so powerful, and it really gives new meaning to the interpretations of his paintings and his attempt at reconstructing the human figure after surviving genocide.

V: Can you tell me a bit more about his artistic style? It looks very unique and very contemporary.

A: He was quite unique and very iconoclastic for his time. His work in the 50s definitely had a little bit of this zeitgeist of the COBRA Group, and also Figuration libre in Paris. There is not just the visual similarity with COBRA artists, but also a shared conceptual grounding in processing the traumas of war and genocide. The COBRA group was writing a lot of very political texts, for example the artist Constant coined the phrase “human animals.” The question of human-animal hybridity is something that you see as well in Maryan’s work at that time. And the theme of the sacrificial bird, which repeats a lot in his work comes not only from this human-animal idea as a result of wartime trauma, but also the sort of Jewish ritual sacrifice of a rooster which really marked him as a child. And then at the end of the 50s and the beginning of the 60s, he really finds his mature voice and starts to make personnage paintings with black outlines and a very strange, cartoony figuration starts to appear in his work. And then when he goes to America he gains confidence in his mature style and he enters into a dialogue with artists that were mostly associated with figurative art being made in Chicago.

V: And if I understand well, it’s his first retrospective, this one in Miami curated by you, so could you tell me a bit more about the exhibition itself?

A: The show begins with a kind of approximative reconstruction of Mayan’s studio at the Chelsea Hotel in the 70s. I came across unpublished photographs of Maryan’s apartment and studio, where he covered the walls not only with his paintings but also with African and Oceanic masks and Polish folk objects, so he was surrounded by all of these personages and these heads. The exhibition begins as well with an optical assault of Maryan’s late style, when he’s really at the height of his artistic powers. There are as well two places in the exhibition where I wanted to reinsert him into an actual dialogue with his peers: one cluster of works which mixed his early paintings of the 1950s with the COBRA Group, and his works from the 1960s with his American peers H.C. Westermann, June Leaf, Leon Golub, and Dominique De Meo–these artists that were known as the “Monster Roster” in Chicago. I felt it was really important to have actual works by other artists, so you could really see those affinities and also to kind of seduce the American viewer, who will know those artists and then see this connection and see how Maryan really belongs in this dialogue. When you see them side by side on the wall, Maryan’s work is as powerful as these more familiar figures.

At the very center of the show is a whole room devoted to the film and archive of photographs that we found, and the works he made in Israel, which have never before been shown. There is a crematorium painting of Auschwitz from 1949, another early painting called The Yellow Star from 1947, intimate drawings he made around Jewish themes in the very early 50s where he was sort of probing all of this Jewish iconography. And then we have a very powerful slideshow of the five hundred-plus autobiographical drawings he made when he had his breakdown in the early 1970s. And then in the very last room, there is a series called After Goya, where he repainted Goya’s Dead Turkey. He made 15 iterations of the Goya still life right before he died, which eerily foretells his early death from a heart attack in 1977.

V: With Erna it is the opposite situation: it’s her first solo show outside of Poland. Can you tell me why it’s happening now and why at Hauser and Wirth?

A: As I said earlier, firstly this project was an independent research project that I worked on for over five years and I tried to place it in different museums. When I met with Hauser & Wirth, they completely understood this artist, unlike all of the other meetings I had where I had to explain Polish history and Erna and all of the back story. And they also immediately connected her to a number of women artists that they work with. Whether it’s Louise Bourgeois or Alina Szapocznikow, they saw numerous parallels. So I was thrilled to be able to organize the show as if it was in a museum. We borrowed many works from fantastic Polish museums and foundations. It was really like being a kid in a candy store, being able to show the very best examples of her work and making this important introduction to both the New York and international audience.

V: And what is the recognition of Erna’s art in the U.S.? Is she considered an important Polish-Jewish artist?

A: She’s a real discovery for people. There is also another interesting coincidence: the show was supposed to happen in April of 2020, but because of the pandemic, it had to be delayed and finally we opened Erna’s show two weeks before the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened their global Surrealist show. That exhibition looks at the very narrow canon of French Surrealism before the war and expands it to artists literally from every continent, and they included Erna in that exhibition. And I think that just gives you a sense that the American establishment is eager to rethink fixed ideas about even the most popular movements like Surrealism. So at this moment, Erna is being received with very open arms, and I keep hearing over and over again: “I can’t believe we’ve never heard of this artist before. I can’t believe she was never shown in America before. I can’t believe she was never shown outside of Eastern Europe before.” It’s been really great timing.

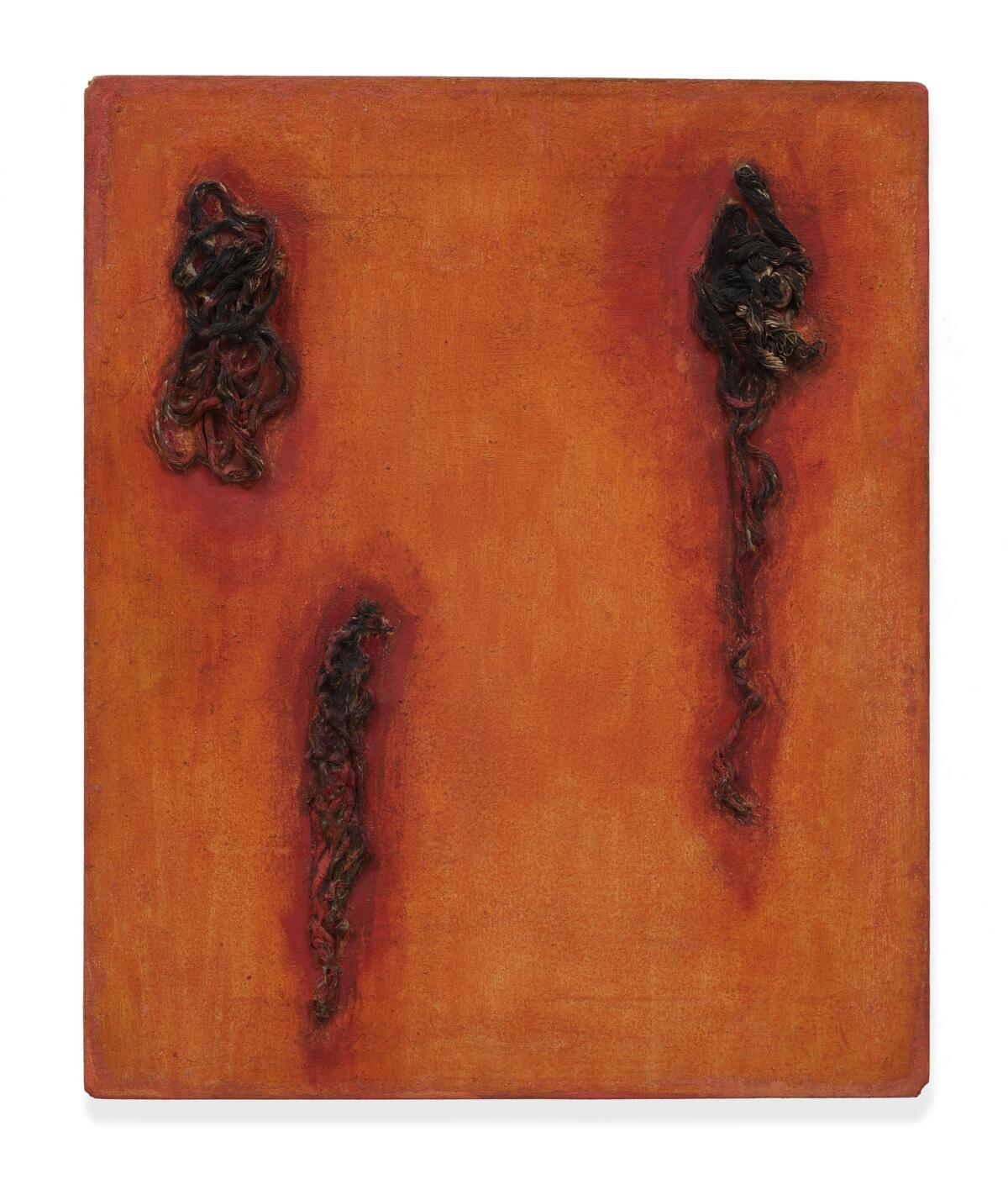

Erna Rosenstein, Obecność (Presence) 1990 Oil on canvas with twine frame 56 x 39.5 cm / 22 x 15 1/2 in

V: As far as I know, you decided to reconstruct a part of Erna’s solo exhibition from the Zachęta in 1967. Could you please tell me about the exhibition itself and your curatorial decisions?

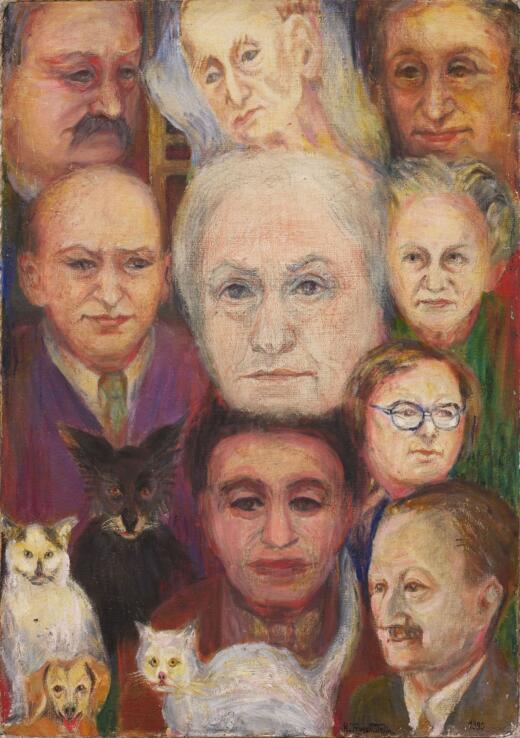

A: A part of my method has always been to study the archive whenever possible. And when I went to the Zachęta to look at their archives, I was fascinated by photographs of the scenography that Erna invented with Tadeusz Kantor, and the way that he brought this Szafa (Closet) from her house and put it in the center of the show like a kind of magical cabinet around which he hung all of her paintings. And then I saw an incredible accordion-like wall, a zigzag that traversed the space. I felt that this was an interesting gesture to not exactly reconstruct, but to make these sort of acknowledgements of the experimental culture that Erna was part of with the Kraków Group, being such an important emblem of the avant garde in pre and post-war Poland. And I thought that it was an implicit way of staking Erna’s claim to her place in the canon of the avant garde. I also wanted to make sure that the show registered the full scope of her practice from her well-known more abstract, biomorphic landscapes starting in the fifties to her more figurative works, especially the ones that directly deal with her parents. Because, obviously, none of the work that she made before the war survived. But I think that she deserves to be considered in this continuum and not just as some latent Surrealist. By organizing the exhibition in this way, I hoped that it would be evidence for this argument. And it was also important for me to showcase the importance of Erna’s literary practice as a writer and poet. So we borrowed drawings from the national library which were the illustrations of bajka (fairytale), and in the catalogue we made, we translated the story which was never even published in Polish. To me, these stories are often allegories of her own experience, told through the kingdom or community of animals. So that’s a big part of the show, and I think it registers the duality of her work, both as a visual artist and as a writer. We also included her sculptural objects, which were exhibited with the drawings because I felt a childlike wonderment within those objects, which really spoke to the fairytales that she wrote. The show concludes with a span of works that take us to her latest pieces. And I think that what she made at the end of her life just shows how she remained such an inventive and consistent artist. The quality of the work is there until the very end. I wanted to make it obvious for the viewer.

V: How did you manage with the diversity of her works, with the fact that Erna created both abstract and figurative art?

A: In the first room, the abstract triptych from the National Museum in Warsaw is presented. But on the back outer wings of the work we can see Erna’s parents’ heads, and there is the small painting Bardzo Dawno (Once Upon a Time), which was the little train with her parents’ heads above. The show starts with this dialogue between the two sides of Erna’s practice–abstraction and figuration. And then in the second room, there is an accordion wall, the zigzag with only the abstract paintings. I could even say that they’re not abstract, I see them like alchemical biomorphic landscapes. And then in the third room there is the cabinet with only figurative paintings, and all of those paintings directly reference her experience and her kind of dream-like reimagining of her parents, her life, and social and historical phenomena. There’s for example this wonderful painting called Pomniki (Monuments) that portrays these monumental bones as columns or heroic monuments in a landscape.

Erna Rosenstein, Nad głowami (Over the Heads), 1967, Oil on canvas with artist frame, 61 x 51 cm / 24 x 20 1/8 in

On the second floor of the exhibition, there is a fairytale room featuring drawings and sculptural objects shown together. And then the very last room mixes all the periods together and shows the interweaving of abstraction and figuration, even assemblage, because a lot of those late paintings have objects in them, like broken glass and other objects.

V: What is the content of the book published in connection to the exhibition?

A: There’s the main essay that I wrote which reads her entire oeuvre through the lens of the fairytale as a throughline in her work. There is also an essay contributed by Polish art historian Dorota Jarecka. We published a translation of Erna’s Shoah testimony, which was given in the 90s when the USC Shoah Foundation went around the world to film survivors. We translated it to English and condensed it. We also selected some of Erna’s poems, translated them into English and paired them with works. There’s the fairytale, the tiny tale of the snail and all of his friends with the drawings. And then there’s an illustrated chronology that traverses not only Erna’s life, but the kind of political and artistic context of Poland so that a foreign reader has the important events explained, and can see how they impacted Erna’s life.

V: When I look at Erna’s works now, especially the figurative works which comment on traumatic experience, like sewn lips for example, for me it starts to be more and more essential to the situation which is happening now in Poland. I’m just wondering how it has been received in the US, like as historical evidence or also something as relevant to the contemporary situation in the world?

A: I’m probably not a good person to ask because I’m very tuned in to what’s happening in Poland. So my own perception is colored by that awareness. But I would definitely say that her work, especially those figurative pieces that you’re talking about, carries a very haunting presence. I think there’s a universal human experience in those pieces. So when you see a mouth that’s sewn or a hand that is severed, there is an obvious trauma, and even maybe a very dark humor in the work that would be legible to a non-Polish person. Like there’s a painting called A Very Jolly Death, which is like a ghostly face formed with shards of broken glass. The face is smiling. I think that there’s a sense of struggle and survival in Erna’s work, but there’s also a certain amount of optimism in survival. It was interesting to me to learn from curator Anda Rottenberg, who knew Erna since 1969, that she didn’t know about this show of testimony until very recently, because in the 60s and 70s Erna didn’t walk around talking about her parents and what happened to her. So I think that an important thing to realize is that the back story that I am telling in this exhibition is very up-front and was not necessarily shared with people who saw the work when she was making it. And I wonder a lot about what people think about these paintings of these floating heads. Did they see them through this lens of trauma or not? I think that there is a universal humanist message in these paintings that come across, even to someone who doesn’t know her full history.

V: My final question is about your revisionist curatorial methodology and your anarchic approach to art history, what do you exactly mean by that?

A: Well, I’m always looking for who has been left out, who was too hard to deal with or tame into a neat account of a given period. I’m always interested in what didn’t make it into the first draft of art history and what deserves to be reconsidered. What, who was repressed, too difficult or just too weird or too much, or too against the grain or the orthodoxy? That’s what I’m attracted to in art history. And I think in both cases, of Maryan and Erna, that these artists made such significant and vast bodies of work, but they couldn’t be fully metabolized in their lifetimes. And it sometimes takes like 20 or more years of distance to really appreciate and understand the complexity of practices like theirs. I also enjoy these projects where you become like a detective, with Maryan in particular, because Erna had much more evidence and much better archives, but with Maryan, we didn’t have this. And so it was really an incredible challenge to hunt down whoever I could find that could share their oral histories, finding his unknown works and materials that he left behind in Israel, letters in Hebrew and photographs of him, discovering for example that he chose to live in this Ottoman prison because he didn’t want to live in an apartment, when he was a student in Jerusalem. So in my curatorial practice I just started to put together a story, and that process is really exciting to uncover bit by bit.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Erna Rosenstein / Maryan |

| Exhibition | Erna Rosenstein: Once Upon a Time / My Name is Maryan |

| Place / venue | Hauser & Wirth NY / Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami |

| Dates | 30 Sep – 18 Dec 2021 / 17 Nov 2021 – 20 March 2022 |

| Curated by | Alison Gingeras |

| Website | www.hauserwirth.com/ |

| Index | Alison Gingeras Erna Rosenstein Maryan Vera Zalutskaya |