1.

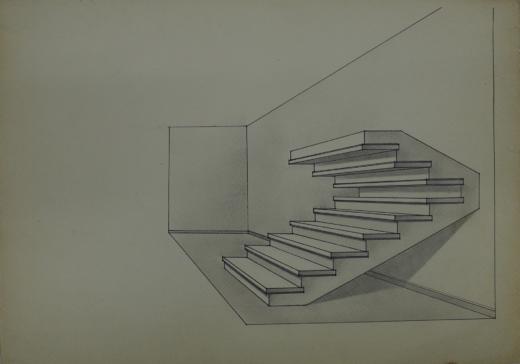

One of Zdzisław Jurkiewicz’s works of the late 1960s/early 1970s, the period of artist’s conceptual opening towards media other than painting, is a drawing captioned Schody nieosiągalne (1970) [Unattainable Stairs]. Status of this work is an ambiguous one. Brittle, almost technical nature of a drawing allows us to perceive it as a design for an utilitarian construction. However, depicted staircase reverses its course after seventh step, as in miror reflection, making further climbing impossible from now on. On the other hand, there is nothing particularly illogical in this object, at least in its constructional aspect, and it would be easy to build basing on what’s being shown in the drawing. Hence, it is difficult to assume that the drawing is only a visualization of an unrealizable design.

Bracketing the conceptual dimension of the discussed drawing, let us provisionally focus on its spatial aspect. Staircase, which gets mentioned in the title, is depicted as isolated from architectural structure: it constitutes self-contained object, leaning against the wall of a box-like space, unavoidably bringing about associations with gallery space. Rhythmical slides of successive steps and nearly obvious construction principle (surely known from everyday life) connect it to the whole context of American minimalism, to its rule of the simplicity of shape, at times supplemented by syntax of repetitive elements.

Jurkiewicz was well-versed in this context: he studied it perceptively in the latter half of the 1960s, reading the articles from foreign arts-related periodicals, mostly „Artforum” magazine.[1] He went as far as to recognize „Minimal art”, as he termed it, as instrumental in breaking of the formalistic impasse, in which according to his diagnosis contemporary painting has been immersed in at that period. „Don Judd and Robert Morris”, he recounted, „view >>the virtue of continuity, singularity and indivisibility<< as fundamental for minimal art… According to them, work of art has to be, as far as it is possible, >>an unitary thing<<. In addition, Morris, while pointing to >>gestaltism<<, prefers single >>strong shape<<, while Judd tends to choose repetitions of identical units”.[2] In this current, „only shape has been deemed as important, simple and often symmetrical shape […] almost geometric as well”.[3]

Characteristic problem: Jurkiewicz fights with formalism in painting, basing on strictly painterly premises, he does not intend to take the notion of the artwork beyond the discipline of painting in order to connect it, as Morris did, to the discipline of sculpture. His alliance with an object is of temporary and experimental nature.

According to Jurkiewicz, „reconstituting art as object” resulted from an infallible logic of art’s development, it was a fact „permanently eliminating illusionism and metaphor”.[4] As if in response to Judd’s and Morris’s statements which announced the formula for minimalist art, he begins to associate his own works with the notion of continuity as early as 1967, employing a solid which can be characterized by its relative simplicity of shape. Its employment did not yet prove that Jurkiewicz’s practice has been relocated into the domain of sculpture. Rather, it resulted from painting-related premises, being intended as a polemic with minimalist guidelines, in particular with Morris’s concept of the unitary form. It was a manner of resolving of then-actual argument between „hot” and „cold”, or between emotional/spontaneous attitude in painting and rational/geometric one. This argument engaged Jurkiewicz himself, who thus far created compositions in the vein of gestural painting.

Influenced by notions of continuity and simplicity of shape drawn from Judd’s and Morris’s writings, Jurkiewicz attempted in the latter half of the 1960s to solve aforementioned argument, connecting painting to colour symbolism. „Geometricized”, somewhat >>warped<< objects”, which were included in his solo exhibition at the Mona Lisa Gallery (1967), „are specific event field for various – predicted or random – courses of spilling colourful mass”.[5] In these works, dried gush of paint spews forth from circular or conical concavities made in the walls of white cuboid solids. In one case, it wanders into the direction of the positive form placed next to a cuboid, it „climbs” up the former’s side, to penetrate its interior. In this work, colourful mass „wanders” between the Pole of Hot, which is marked by colour red, and the blue-marked Pole of Cold. The sense of a gush of paint being animated evokes here the notion of process. At the same time, gravity-defying course of the gush suggests that this process occurs in the mental sphere.

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘Unreachable Stairs’, project: 1970, realization: 1999

In the objects under description, as their creator explains, „canvas surface has been replaced with a surface of solids. It was still paint’s natural happening, it was an excitement of that which is occurring, of showing the history of a spilled paint, steered by hand’s will to varying degrees”.[6]

Employment of a minimalist solid, along with polarization of red and blue which was staged by the artist, serve to visualize the notion of continuity beyond the compositional order, with its appurtenant dichotomy of form and bakground. He has manifested generalized extrapictorial sense of continuity in a more radical manner in Environment w pulsującym czerwonym i niebieskim świetle [Environment in Pulsing Red and Blue Light] (also known under its alternate title Niebiesko-czerwone światło pulsujące od 0 do maksimum) [Blue-Red Light Pulsing From 0 to Maximum] which was realized in Galeria Współczesna (1969). In this work, tendency to modify solid shape, as qualified by Morris, grew stronger. Objects made of card stock or plywood, which Environment consisted of, were described by „geometry of curves, impossible to frame in any mathematical formula”.[7] These were predominantly solids of shape close to a cuboid, some of them juxtaposed into twin pairs, subject to different kinds of distortions, and to a lesser degree also cylindrical forms, one of them bulging in its mid-heigth, the other conically tapered upwards. One of two (as seen in the photographs) cylindrical forms, small-diameter cylinder of two meters, has been furnished with narrow notch, coursing in spirals along its whole length.

Scale of these objects, stimulating receiver’s reaction not only on optic, but also on corporeal level, corresponded to Morris’s postulates concerning the size of solids.[8] It seems that, by constructing them, Jurkiewicz took postulate of a direct impact of minimalist objects into account. After many years, he confessed that „communion with large objects in small galleries, a sort of physical feeling of coexistence with their absolute presence, was poignant”.[9] These words can be referred to the drawing Schody nieosiągalne: condensation of a space shown therein, resulting from technical foreshortening that artist has used, is expressive of the meaning of directness in object-recipient relationship. Moreover, artist has been „fascinated with the technological value of American artworks, which were reduced to the maximum. But they were using steel and fiberglass, whereas we had plywood and cardboard at our disposal”.[10]

However, distortion of regularity of minimalist Gestalt[11], both in the objects constituting the scenery for red-and-blue paint courses, and in objects being the constituent parts of Environment w pulsującym czerwonym i niebieskim świetle, seems to be telling in this context. In the latter work, main factor weakening object’s integrity was the employment of „gradually increasing and decreasing blue-red light” in which „objects lose their status of permanence: continuous blue-red space is in existence”.[12] Jurkiewicz explained the reasons for dissolving of miminalist solid, referring to solutions of his-contemporary physics. He accepted that Environment can be perceived in two ways: „On >>macro<< level – world of specific shapes >>to be drawn<< […], on >>micro<< level – world of indentical particles, flowing as in a gas tank, chaotically, >>pointlessly<<”.[13] According to this view, „macro” level would be restricted to the sphere of sensual interaction with minimalist solid, while „micro” level would engage mental sphere, evoking ideas from higher level of abstraction than the notion of minimalist Gestalt, or „shape of continuity”. Jurkiewicz has acknowledged that Environment „was not a matter of objects, but continuity breathing in blue, violet and red”.[14] In this way, hot-cold argument that the artist has been engaged with, has been transferred from the sphere of sensual perception into the domain of free play of imagination and notional abstraction.

In this way, formula of Jurkiewicz’s work as a quest for the „shape of continuity”, seems to emerge: according to his intention, consecutive manifestations of continuity are to reveal new meaning of art each time. Artist has acknowledged that shape cannot be anything static and finished, perceiving it rather as an object of anticipation which undergoes ceaseless change.

Where does Jurkiewicz’s distrust for homogeneous solid, as postulated by Morris, come from? Reason for this seems straightforward: psychological notion of Gestalt, to which Morris referred to, understood as a distinctly defined shape on a specific background, retains in Jurkiewicz’s optics its painterly meaning, he associates it with the notion of form. As such, it was unable to live up to its role of a solution enabling to rescue painting from the formalistic impasse. Characteristic problem: Jurkiewicz fights with formalism in painting, basing on strictly painterly premises, he does not intend to take the notion of the artwork beyond the discipline of painting in order to connect it, as Morris did, to the discipline of sculpture. His alliance with an object is of temporary and experimental nature. As early as in 1967, in a text accompanying exhibition of his modified cuboids at the Mona Lisa Gallery, he expresses his aloofness against then-domineering tendency to objectify art, which obliterated boundaries between art and non-art. He claims: „Despite conscious choice, objects remain what they are. Subjecting them to camouflage or destructive procedures seems to be equally artificial as aesthetic play”.[15]

However, he does not totally reject the notion of shape, as proposed by Morris. Retaining its qualifications of simplicity (comprehensive nature – lack of component parts) and, by the same token, its continuity, he comes up with the concept of shape, which has bothered him at least since the time of Environment realization, and in which detachment of continuity from an object was about to take place. According to this concept, „there is no object-space opposition, in which objects are >>immersed<<. There is no something in something else, there is oneness: Imaginable, perhaps, but impossible to be realized: >>somethinginsomething<<”.[16]

Motivated by an impulse to transgress formalistic limitations in painting, in a transgression identical with the cessation of fruitless „hot” and „cold” arguments, Jurkiewicz abstracts continuity from specific materialization, taking it beyond strictly painterly context, conferring upon it the status of a notion . Henceforth, in his artistic practice he would be focused on delivering successive definitional designations of this notion. This turn marks the beginning of conceptual phase in Jurkiewicz’s work: the notion of continuity, faced with the multiplicity of usable media, will play a primary role in it.

In this way, formula of Jurkiewicz’s work as a quest for the „shape of continuity”, seems to emerge: according to his intention, consecutive manifestations of continuity are to reveal new meaning of art each time. Artist has acknowledged that shape cannot be anything static and finished, perceiving it rather as an object of anticipation which undergoes ceaseless change. The notion of shape has been constructed by Jurkiewicz in a constant dialogue with other artists. Let us attempt to inspect selected threads of these dialogues, aiming to explicate the meaning of this notion and its correlated concept of perception.

2.

Direction of Jurkiewicz’s explorations is compatible with the specific line of thinking of art in the Polish context since the political Thaw which perceived it as a scientific discipline, a kind of theoretical knowledge endowed with a distinct range of issues and its proprietary research methods. This scientific model connects art to the category of progress, recalling ethos of pre-war avant garde. It was Władysław Strzemiński who emphasized the division between pure and applied arts, associating the former with the task of exploring and perfecting form.[17] Jurkiewicz also has associated his artistic activity with the rhetorics of the scientific discovery, making those Polish and international artists whose findings were valid to him and enhanced the condition of artistic consciousness of his times, partners for his dialogues. In his optics, the object of artistic research is a „progressive meaning of art”, as „significance of historical facts is irrefutable: matter painting is the 1950s – minimal art 1960s – conceptual art 1970s”.[18] Distinguished addressees of the polemics he conducted were American minimalists and conceptualists. In his view, conclusions made by many of them contributed to the most vital current of contemporary art with which he identified himself.

Painterly lineage of Jurkiewicz’s art connects his notion of the shape, as developed in the late 1960s/early 1970s with Frank Stella’s formula for painting. Jurkiewicz has repeatedly stressed the importance of experiments in painting stemming from the tradition of abstract expressionism. He expressed it most explicitly in a theoretical declaration which bore certain marks of the manifesto, delivered during Osieki Plein-Air in 1970.[19] In his declaration, he emphasized importance of dealing with „almost gigantic size of canvases”, where sheer size of the objects leads to marginalization of the problems of formal structure. Reflecting upon Kenneth Noland’s paintings, „his long, impossible-to-be-taken-with-one-glance, triumphal horizontal stripes”, he called it „the victory of the unpredicted”. Regarding Noland’s composition Via Blues (1967), which exposed an array of horizontal narrow colourful stripes on 228 x 671 cm canvas, he wrote: „Practically, this peculiar >>environment<< has >>neither beginning nor end<<: spectators experiences the feeling of >>violent pull and merciless rush<<”.[20] He also acknowledged that „lingering perception of huge colourful shapes is an effective transmission to areas of thought and painterly reflection”.[21]

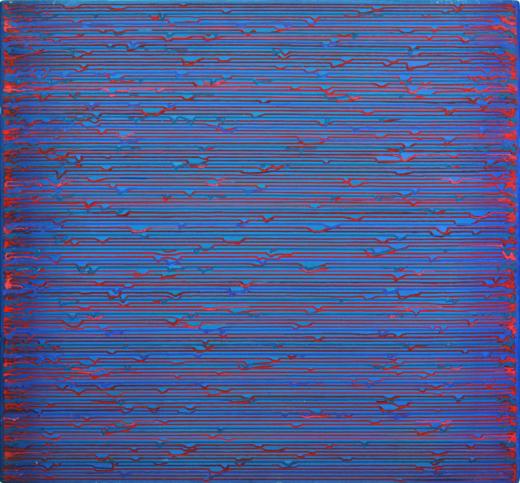

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘Continuum C-N’, 1970 oil, canvas, 133,5 x 121,5 cm, Culture and Art Centre in Wrocław

In his opinion, painting belonging to this tradition offered sensation of a „total takeover of eyes”[22] which he has experienced for the first time, as he recalled after many years, looking at Willem de Kooning’s painting included in the exhibition Współczesne tendencje – malarstwo ze zbiorów Stedelijk Museum w Amsterdamie [Contemporary Tendencies – Painting from Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam Collection] shown in 1966 in Warsaw’s Zachęta.[23] Describing his perception of paintings by Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland and Frank Stella, which he has seen during his T. Kościuszko Foundation grant in New York in 1976, he was quite concise: „Impression was massive, escape impossible”.[24] He also ascertained that „new works in the vein of >>coloured surface painting<< and >>sharp contour<<, most often in huge dimensions, created an overwhelming breath of environment, mercilessly dragging the viewer into its blissful or cheerless doom of all-prevailing colour”.[25]

In particular, Jurkiewicz appreciated „giant objects, breaking with traditional square-shaped frame – Frank Stella’s object-paintings from >>irregular polygon<< series […] constituting exactly an external shape of an object-painting. Powerful impact is also the characteristic of later series of circles and their combinations […]”.[26] He infallibly recognized new quality manifested in shaped canvas type paintings, their obtrusive physical aspect accentuated by modular structure of the composition. It seems that the notion of shape, as worked out by Stella, was for him even more relevant than deliberations of minimalist Gestalt, as conducted by Morris. However, similarly to the reception of Morris’s works and texts, Jurkiewicz interpreted Stella’s concept in his own way.

Jurkiewicz explained the reasons for dissolving of miminalist solid, referring to solutions of his-contemporary physics. He accepted that Environment can be perceived in two ways: „On >>macro<< level – world of specific shapes >>to be drawn<< […], on >>micro<< level – world of indentical particles, flowing as in a gas tank, chaotically, >>pointlessly<<”.

Regarding the manner in which Jurkiewicz has perceived shape, it may be useful to recall Michael Fried’s musings, as they were voiced in an essay Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s New Paintings (1966). They regard the tendency for emancipating shape from traditional closed relational structure of the painting, tendency manifesting in post-war American painting, and culminating in Stella’s painting-objects. In this essay, Fried describes changes occurring during post-war twenty years of American painting which stimulated Stella to consider frame shape as one of the most important elements of painting’s construction. He writes of viability of shape in Stella’s paintings, suggesting that shape became for painter an object of conviction.[27] He states that by „shape” Stella refers neither to frame silhouette, nor to shape painted on a canvas, but rather to shape understood as a kind of medium within which choices about both literal and depicted shapes are made.[28]

Fried’s considerations are based upon distinguising of the physical flatness of painting from the surface of painting understood as a consonance of painterly values obtained through specific placement of pigments and texture modelling. Fried remarks that in painting grounded in tradition of abstract expressionism, these two structural elements of picture fit in with each other, which results in „ The emergence of a new, exclusively visual mode of illusionism in the work of Pollock, Newman and Louis”[29], or illusionism of all-over type, based on uniform distribution of compositional elements on the surface of canvas. As it were, this illusionism sublimates physical flatness of the painting, leading to a value defined by Fried as literalness of the picture surface, which he also described as illusionistic presence of the painting as a whole.[30] According to Fried, in this sort of practice, counterdistinction between attending to the surface of the painting and to the illusion it generates is missing.[31]

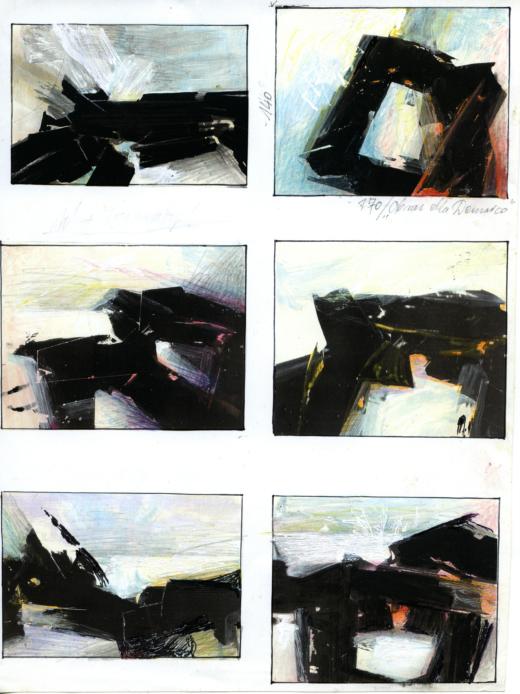

Jurkiewicz consciously steered his painterly activity of the 1960s in the direction compatible with the transformations occurring in post-war global art, not only with American painting but also with its French counterparts (in an interview with the author of this text, he confirmed his fascination for artistic output of Soulages)[32] He did it in methodical way, apparently governed by the intention of testing ready solutions for his own purposes. He defined his paintings from W akcji, Agresje, Inwazje series [In Action, Aggressions, Invasions] (1961-1966) as

[…] from formal point of view close to gesture painting. It is not the gesture of spatter and blotches, this gesture is the means for accomplishing preconceived task, course of certain forces and tensions. Dominating expressive sign, often cutting canvas diagonally, is decisive of the expressive nature of this painting.[33]

However, already in this period he was bothered by doubts concerning the validity of contemporary choices regarding painting’s formal structure. After many years, he confessed:

I was puzzled by the problem of choice of a specific course of composition in an inifinite number of other possibilities. Why do I choose precisely this solution? Maybe I should pick something different? Even if I would paint several hundred versions of Agresje, I could always say that it’s still not the right one. That’s why I eliminated all forms, with just a muddle of paint remaining in the background.[34]

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘Sketches for Aggressions’, 1960s mixed technique, paper, various sizes, the artist’s archive

Tendency for embedding of painterly form into picture’s background is actualized in Strefy series (1967‒1969), where familiar (from Inwazje and Agresje series) diagonal courses of spiky forms give way to complex structures exposing multidimensionality of painterly matter’s expansion. One of these compositions, Strefa czerwieni i błękitu [Zone of Red and Blue] (1968), seems to launch undulant strands of red and blue (as in work’s title) into circular or gyratory movement, suggesting continuty of moving between them. As artist wrote:

In subsequent Strefy [Zones] series, opposition between shape-sign and background vanishes: there is almost monochromatic, shiny, whirly space of varied degree of density. „Object” field filled with signs is replaced with a field of tensions. Illusive surface of canvas seems to be insufficient.[35]

Therefore, procedure of reduction of painterly composition to its background does not result in radical simplification of it. In a homogeneous composition obtained through using of this procedure, richness of painterly values is manifested which, according to Fried, characterizes „literalness of the picture surface”, as opposed to flatness of the painterly groundwork in a material sense. However, following the trace of Jurkiewicz’s autobiographical narration, tendency for heightening of dramatic tension between homogeneity of painting’s optical space and its physical flatness, is growing stronger in his works from the late 1960s.

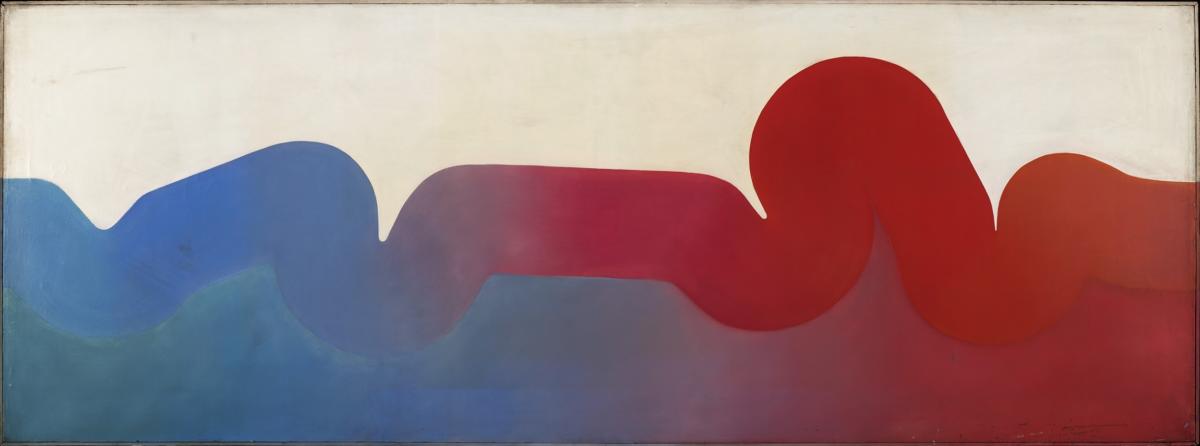

In Continua series (1969‒1971), which has been initiated shortly after Strefy, continuity of painterly surface, which has been achieved in Strefy, is polarized as a closed-course band between poles of red and blue, reminiscent of Möbius strip. In at least three works of the series under discussion, white, which almost merges with the whiteness of picture’s background, forms an intermediate phase between these colours. In other compositions from this group, continuity of the colour band is relatively independent of background colour.

Aforementioned „geometry of curves, impossible to frame in any mathematical formula”[36] concerns exactly this type of background-paintings. Jurkiewicz aims in them to neutralize opposition between figure and background, making a sort of a radical overturning of a painterly illusion onto literal surface of a painting. He collides painterly illusion against surface’s concreteness, establishing a kind of continuity between them. While making it, he extracts – incidentally, in some ways – physical shape of the canvas as work’s structural element.

I was puzzled by the problem of choice of a specific course of composition in an inifinite number of other possibilities. Why do I choose precisely this solution? Maybe I should pick something different? Even if I would paint several hundred versions of Agresje, I could always say that it’s still not the right one. That’s why I eliminated all forms, with just a muddle of paint remaining in the background.

At this point, as it seems, creative pathways of Jurkiewicz and Stella appear to converge. In deliberations quoted above, Fried wrote of a certain discovery made in American painting, the discovery shortly before 1960 of a new mode of pictorial surface based on the shape, rather than the flatness, of the support.[37] This new mode conferred upon a frame shape much more active role than it was previously thought. Fried ascribed this discovery to Stella, in his opinion

[…] by actually shaping each picture […] Stella was able to make the fact that the literal shape determines the structure of the entire painting completely perspicuous. In each painting the stripes appear to have been generated by the framing-edge and , starting there, to have taken possession of the rest of the canvas, as though the whole painting self-evidently followed from, not merely the shape of the support, but its actual physical limits.[38]

This new status of the surface of painting applies to Stella’s Black Paintings series (1958–1960), which were still made using traditional square-shaped frame. In his slightly later paintings of shaped canvas type, absolute subordination of shape to represented physical shape takes place, as if depicted shape has become less and less capable of venturing on its own, of pursuing its own ends and have become dependent upon literal shape.[39]

Fried singles out “frame logic” as applied by Stella according to which painterly composition is consistent with the structural properties of the groundwork on which it is painted. He writes about deductive structure of these works: pattern of parallel pigment stripes replicates frame shape, with width of shapes being equal to the frame width. Paintings with indentations effectively undermine figure-background opposition. As Stella himself has stated, applied solution forces illusionistic space out of the painting at a constant rate by using a regulated pattern.[40] This suppression is facilitated by symmetrical structure of paintings which neutralizes model of relational composition, subordinate to the principle of balancing of painting’s compositional elements. Employment of frame logic results in an utter accord of work’s physical component with representational element.

Jurkiewicz associated self-reflexivity of Stella’s works, a kind of reverberation between painting’s physical margins, and its internal structure, as narcissistic in its nature. He wrote that “Stella pointed to the picture-as-picture-of-picture-itself. Picture with no past and no future (without those arbitrary sophisticated commentary by art critics), picture staring at its own shape”.[41]

There are many indications that Jurkiewicz’s experiments in painting from the late 1960s/early 1970s take painting’s physical flatness into account and, as a consequence, that he also conceived canvas’s square as a physical shape. Later, he explained that these works are not about “imaging” of anything, or transmitting any “internal moods”, and they are not images-author’s showpieces. Picture is exclusively a plane for conducting certain “experiments”, it is a surface presenting, as fair as it is possible, “objective” result of speculations regarding picture.[42]

Despite this, he prefers to be cautious about the principle of superiority of literal shape over represented shape, as distinguished by Fried regarding Stella’s painting. In paintings from Continua series, colour strip as a represented shape seems to make its course independent from painting’s flat background, making only local contact with it. In other words, while positively sanctioning painting’s physical flatness, and – as a consequence – its shape as well, represented shape begins to function independently of the flatness. Setting the optical continuity between colour zones, and acting as its clearly legible sign, it simultaneously shifts the reflection on continuity to a notional level. Paraphrasing Fried’s definition of shape quoted above, it can be concluded that in Jurkiewicz’s work shape functions as medium, by means of which choices concerning both depicted shape and conceived shape, are made.

3.

Making no use of structural resolutions worked out by Stella, Jurkiewicz does not detach himself from a broader tendency to relocate artwork to a notional level which is manifested therein. Transparency of the deductive procedure employed by Stella seems to be the factor stimulating his own artistic decisions. Stella’s exclusion of optical illusion from compositional order confers upon his paintings literal character which is defined in the following way:

My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there, is there. It really is an object. […] All I want anyone to get out of my paintings is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any conclusion. What you see is what you see.[43]

Thus, act of inspection of Stella’s artwork is of full and adequate nature: seeing painting is in it synonymous with recognition of the idea determining the manner of its construction. Also Jurkiewicz stands for a model of a perception enhanced by notional element, and he does it already in the moment of discarding “intermediate world”, which took place in his Environment, in favour of exploration of the domain of interactions between elementary particles, or photons, as described by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. This shift of attention has been earlier announced by Jurkiewicz’s quasi-minimalist objects of 1967 whose clearly defined shapes, as we remember, became opposed to spontaneous courses of colourful gush.

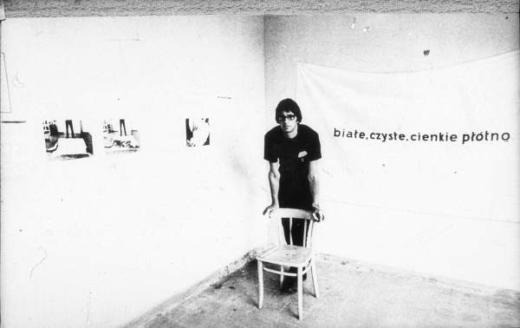

Experience characterized by fusion of sensual and notional components is also present in Jurkiewicz’s tautological works which were created since 1970, with first one of these being painting-event with a self-reflexive title Białe czyste cienkie płótno [White Clean Thin Canvas] (1970). It is difficult to discuss this work in terms of homogeneity of artistic medium as it consists of an object, fabric with printed words from the title, for which artist creates equivalent in the form of photographic representation (lateral shot of a spread fabric, exposing its flexures and folds). At the same time, object is used as a substrate for activity conducted with the participation of a model (four posed photographs done by Jurkiewicz, and shown during first presentation of the discussed work at Osieki plein-air in 1970, constitute a kind of documentation of this activity). In Jurkiewicz’s opinion, factuality was the most important attribute of Płótno. As he wrote, “It did not allow for any arbitrary interpretation. None. By no one. It was what it was”.[44]

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘The Shape of Continuity: 33 metres of blue and red’, 1972 acrylic, canvas, 100 × 220 cm, National Museum in Poznań

In the work under discussion, artist unites verbal inscription with concrete of the material: raw surface of the fabric. Linguistic sign is replaced in it with a coloured strip making its course through the surfaces of Continua. It enables neutralization of the painterly problem of oscillation of illusion and literal surface. Making this substitution, Jurkiewicz sustains in his Białe czyste cienkie płótno continuity between notional order and concrete of the material. This treatment places discussed work in proximity of Joseph Kosuth’s tautologies from the mid-1960s, such as Clear Square Glass Leaning (1965) or One and Three Chairs (1965). Latter work has been singled out by Jurkiewicz as emblematic for his own manner of conceiving meaning of art. He acknowledged that “from painting to Kosuth’s chair, transparency and obviousness are properties of authentic art”.[45] Elsewhere, he wrote that in Kosuth’s tautological works “art’s >>spark<< jumps to the present day”.[46]

Jurkiewicz engaged in a dialogue with Kosuth’s Chairs in one of his most important works, spatial arrangement Kształt ciągłości: „krzesło” – „krzesło” krzesło – krzesło [Shape of Continuity: “chair” chair – chair] (1971). In so far as Kosuth raised in his work a question on the possibility of establishing relation of equivalence between object, its photographic representation and dictionary definition, Jurkiewicz’s work can be perceived as a spatial model of semiosis relation, with narrowed version of a chair playing the role of sign, actual chair playing the role of referent, while element of meaning is marked by horizontal straight line between them, including expression krzesło”krzesło” in its course. Jurkiewicz has described this element as “something…which simultaneously is and is not a chair”[47]: it is an an abstraction of meaning perceived as a continuity which expressed itself in drawings and paintings from the 1970s and 1980s in operations of tracing straight lines subordinate to maximally strict formulas.

Białe czyste cienkie płótno and Kształt ciągłości: „krzesło” – „krzesło”krzesło – krzesło can be regarded as works announcing the moment of Jurkiewicz’s effective neutralization of the problem of the formal order of painterly composition. Since that time, artist consistently enriches the range of media useful for constructing or revealing – yet unknown – shapes of continuity. Medium of drawing, which makes maintenance of peculiar fusion (established in arrangement with chairs) of continuous line with linguistic signs possible, gets distinguished among other media. At this moment, line begins to play in artist’s work function of a relay of artistic information. With regard to Jerzy Ludwiński’s speculations on “non-present art”, it plays a role of a sign referring to condition “between” visible elements, to condition of “something-in-something” that has already been contemplated in an installation Environment w pulsującym czerwonym i niebieskim świetle.

Jurkiewicz appreciated the method of composition construction which Stella has proposed, based on deriving its modular structure from frame’s physical shape. In his painterly works from the 1970s, he was engaged in a dialogue with it, without making his way towards (minus several exceptions) using modified frame shape, structural innovation which made Stella famous. However, in Jurkiewicz’s opinion, on the grounds of developing it, „Stella came closest to object art or repetitive objects >>proper<< to minimal art”.

In the early 1970s Jurkiewicz redefines medium of drawing for his own purposes, equipping it with a technical characteristics, and neutralizing its associated subjective connotations, with its connection to the notion of expression, which has been established by artistic tradition. Making use of architectural education, and linking artistic practice with academic work[48] Jurkiewicz confers upon traced shapes characteristics of visual facts, whose objectivity is each time guaranteed by measurement operation. Title of each of the drawings is defined in the strictest manner possible by length of a single continuous line traced in it. Delinaeated shape is accompanied by measurement line with an indication of a scale. Objectivism of these works results from premises which not long before have defined his painterly practice. In his text Rysunek [Drawing] (1971), Jurkiewicz wrote: “We need […] to make art more TRANSPARENT and OBVIOUS, that is, to genuinely confer upon it a status of universality. This is realism, this is matter-of-fact attitude”.[49]

This mode of understanding realism allows him, for example, to trace a line of one-kilometer length, whose bendings cause square shape to emerge, in a work Kształt ciągłości: Kilometr [Shape of Continuity: Kilometre] (1972). The same principle defines the manner of tracing a shape in Kształt ciągłości: 333 333 metrów [Shape of Continuity: 333 333 Metres] (1971) , or three shapes in Kształt ciągłości: 99… 100… 101 [Shape of Continuity: 99… 100… 101] (1972). Many of these drawings came into existence in the 1970s, and their examples could be multiplied. In works from this group, line seems to measure itself, in conformity with the title. Its self-reflexivity, or tautologicality, equips Jurkiewicz’s drawn works with hallmarks of necessity. Each time, self-reflexive principle is enriched by additional rules defining the manner of a continuous line making its course, determining the emergence of varied geometrical shapes, sometimes linked with optical illusion effects.

In the last group of works line changes its direction, so far in conformity with the surface of groundwork, in order to enter illusory spaces compliant with principles of perspective. In those instances, its course assumes shape of three-dimensional objects. In some drawings, these objects are unambiguously reminiscent of paintings of shaped canvas type, hung on the gallery walls, or minimalistic solids gathered in gallery’s interior. In the latter, simplicity of represented shapes is contrasted with hardly-imaginable length of line coursing through them. In this way, Jurkiewicz retrospectively reclaims minimalist Gestalt, introducing it secondarily to his works of notional character.

Also, drawing Schody nieosiągalne, which has been recalled in the beginning of this text, should be treated as a kind of play with minimalism’s convention. It can be assumed that, in time of its creation, it was primarily about to express – in conformity with distinctively Polish poetics of conceptual works – „impossible” idea of climbing up the inverted staircase, or putting it more general, it was a visualization of the idea of neverending movement of continuous nature, with its status of a design of spatial construction, and realization thereof, being of secondary importance. It was symptomatic for tendency of notional harnessing of shape as a defined form, increasingly more representative in Jurkiewicz’s artistic output. This notional edge of Schody has been perpetuated in three-dimensional version of this work, which has been constructed for the exhibition Refleksja konceptualna w sztuce polskiej. Doświadczenia dyskursu 1965‒1975.[50] In compliance with technical drawing which artist has executed for this purpose (1999), this object is builf from wood and plywood. Confronting viewer with its physical presence, above all it offers an experience of intellectual nature.

Continuous line functions in Jurkiewicz’s drawings independently of the paper surface along which it runs. Shapes traced with its aid remain principally neutral against physical properties of the groundwork, its shape and flatness level. Artist has described works under discussion as „drawings showing >>history<< of line. Lines existing in reality, lines in illusory space”.[51] Line traced in them has its material dimension, simultaneously being its own measure. It is only on the secondary level that it connects specific associations with itself, and proposes minimalist objects from recovery, as it were.

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘The Shape of Continuity’, 1967–1973, tempera, plywood, 75 × 75,5 × 10 cm, National Museum in Wrocław

Similar independence of shape from its background is manifested in the concepts of continuous line courses, as registered in drawings by Wacław Szpakowski. This artist has also inscribed shape into a rhythmical pattern of lines coursing independently from groundwork’s square. However, his work stemmed from premises different from Jurkiewicz’s tracing of the continuity shape. As Masha Chlenova remarked (referring to Yve-Alain Bois’s speculations on the need for motivation in explorations of contemporary artists), it was motivated by a quest for conferring form upon certain notional generalizations resulting from observations of nature and human-constructed world.[52] This method is to be characterized, as Szpakowski himself described it in relation to his Pomysły linijne [Linear Ideas], collection of 102 works made partially on the basis of earlier ideas from years 1924-1930, 1939-1943 and 1950. by maximal simplicity, or to put it differently, by economy of means serving „visual harmony”. Principle of tracing which he adopted is almost identical to Jurkiewicz’s tracing rules. According to Szpakowski, „employment of square-shaped refraction, along with proprietary proportionality of course dimensions, creates principal rhythmics of the whole concept or its component parts, being also regular i.e. subordinate to uniform regularity”.[53]

Undoubtedly, Jurkiewicz was familiar with Szpakowski’s linear concepts. It cannot be excluded that he treated his own drawings as an extension of the notion of continuity, as encoded in older artist’s works. Both of them, each in his own way, suspended distinction between literal and represented shape, as proposed by Fried. Szpakowski distinguished optical aspect of his works, He wrote that „By employment of geometrical aspects in an arrangement of linear concepts – for example, symmetries of various types, proportionality of all sections in relation to each other, and other details – linear concepts get close to geometrical activity”.[54] Emblematic character of shapes, which results from employing these geometrical solutions, seems to bring Szpakowski’s drawings closer to Stella’s painterly works. He also wrote of syntactic aspect of his drawings. His linear concepts „possess their >>inner content<< which is possible to be recognized as if through reading the course of a broken line, tracing each deflection one by one, since drawing’s beginning, in the likeness of connecting separate letters, or words in writing. This is a property of linear concepts which distinguishes it from all other ornamental patterns”.[55]

Szpakowski thinks that for interpretation of his works „basing one’s judgment on first glance would be insufficient. It would be an omission of unseen – since they are mental – author’s activities, this is all those fundamental aspects of creativity”.[56] In this way, he establishes the principle of complementarity of work’s optical and syntactic aspects which is analogous to the principle of complementarity of optical and notional aspects, as developed by Jurkiewicz. Szpakowski’s linear concepts spin geometrical narratives, different each time, stretched between diachronic and synchronic orders, between tracing of line’s narrative, identical to learning the principle of its tracing, and immediate shape recognition, effect of its optical unity.

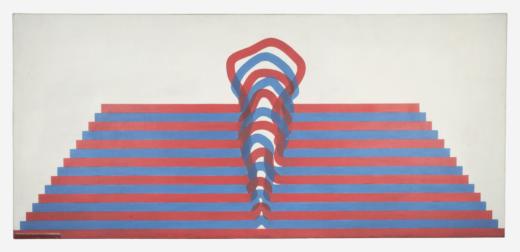

Jurkiewicz appreciated the method of composition construction which Stella has proposed, based on deriving its modular structure from frame’s physical shape.[57] In his painterly works from the 1970s, he was engaged in a dialogue with it, without making his way towards (minus several exceptions)[58] using modified frame shape, structural innovation which made Stella famous. However, in Jurkiewicz’s opinion, on the grounds of developing it, „Stella came closest to object art or repetitive objects >>proper<< to minimal art.”[59] Modular structure of Stella’s compositions recalls Jurkiewicz’s paintings, made using acrylic or oil technique on horizontally oriented canvases, revealing layerings of horizontal blue and red stripes of even width. These works should be regarded as developing the formula of drawings meeting the criteria of transparency and obviousness of transmitted information. As Jurkiewicz recalled:

Line gave us certain possibilities. Guess drawings beginning with line came first, and then there were paintings featuring these wide strips. Again, there was an arbitrariness of bent stripes, like amoebae. In this case, title posed a problem, designation of what’s painted, this damned arbitrariness of title. Titles of these paintings specified length of coloured strips in meters and centimeters, there was a certain degree of literalization in it.[60]

In contrast to drawings, Jurkiewicz’s modular paintings indirectly evoked in their structure physical properties of painterly groundwork its flatness and shape. As Jurkiewicz explained:

If I would paint stripes only, it would be banal, so I tried to diversify them. I’ve painted a certain amount of them using drawing-rule, later stripes gradually became narrower – it’s a pyramid-like outline which has its own history – that which was compressed, became bulging in the centre. Everything measured, with twine applied and bent, so I could honestly say that if I were to extend the upper line, it would equal painting’s width.[61]

In the early 1970s Jurkiewicz redefines medium of drawing for his own purposes, equipping it with a technical characteristics, and neutralizing its associated subjective connotations, with its connection to the notion of expression, which has been established by artistic tradition. Making use of architectural education, and linking artistic practice with academic work Jurkiewicz confers upon traced shapes characteristics of visual facts, whose objectivity is each time guaranteed by measurement operation.

In majority of paintings stripes of red and blue are visibly contrasted, while in several cases they are subdued by an admixture of white. In one of the paintings, Do błękitu i czerwieni, 27 metrów [To Blue and Red, 27 Metres] (1976), colours of stripes are subdued enough to merge with the whiteness of the background. In an upper section of the canvas, on its vertical axis, one can see only pyramid-like crown of stripe layering, bringing to mind an image of atomic mushroom. According to Jurkiewicz, paintings which register irregular courses of stripes refer to remote argument […] between 50s „hot” and „cold”. It was a dispute, fight in which critics and artists […] demonstrated hopelessness and secondariness of all geometry and divisions. This is why I thought that, by proposing these paintings, I participate in this discourse, in a way. Geometry is represented by horizontal lines, while bulges stand for this arbitrary element. Going from geometry of horizontal lines, I creep into arbitrariness of these snake nests. This dilemma is shown in these paintings in a very distinct way.[62]

In other paintings geometrical structures dominate, e.g. in Obraz nr 2 [Painting nr 2] (1975) parallel stripes of red and blue go out from wholly whitened centre of the square frame, and run spirally along painting’s edges, getting gradually saturated with colour. Increasing intensivity of colours and gradual (starting with image’s centre) build-up in stripe width contribute to the creation of an effect of depth. This work gives rise to a series of Jurkiewicz’s paintings which refer to shaped canvas formula, where canvas shapes result from premises determining specific optical effects.

Therefore, a sort of inversion of procedure employed by Stella takes place in these works. Stella assumed logical priority of arbitrarily determined shape over an arrangement of modular elements on the surface of canvas, and rejected optical illusion from compositional order.

In certain modular paintings Jurkiewicz repeats procedure (used in Continua) of establishing continuity between representation of shape of continuous character and groundwork’s physical flatness. Subsequent series of painterly works, Obrazy ostateczne [Final Images], which was initiated in 1975, are to be considered as an extension of the formula for drawings. Line traced in them ran horizontally along the canvas surfaces relatively independently from their physical properties, adjusting its course to presumptions established at the starting point. In these works, artist once more makes use of an operation of tracing, employing in this procedure, as he explained:

[…] a sort of marker of 1-2 mm diameter which is used by architects. I pour blue or red paint in it and simply run along the drawing-rule – using it instead tapes – and making some amount of parallel lines. Final effect was not entirely predictable: I begin with red, and when the red is over, I pour blue one. They mix with each other, causing violet to apppear (…) […] whatever comes out, and I don’t care at all. Now I was finally able to make a painting in a rapid and honest way.[63]

Formula of Obrazy ostateczne addressed the notion of immediacy of a creative act which Jurkiewicz linked to the tradition of abstract expressionism. It also incorporated machinic aspect of artwork’s production. However these works also referred to dichotomy of rational order and spontaneous unpredictability. As artist recalled:

I haven’t been able to get painter’s gesture and unpredictability out of my head. In the beginning, only a drop of paint was sufficient, and it turned at once into a line. But, in order to avoid becoming primarily a technician, I retained certain degree of arbitrariness. Drawing these horizontal lines, I introduced some minor distortions. I was proudly displaying the leftovers of painting. It even gave me certain optical effect, as these waves sometimes overlapped each other, at times causing strange stuff happen to it, for example making it look like a shriveled water. I was able to introduce these distortions rarely or, depending on my mood, I had loop every once in a while, and sometimes I came up with a totally looped painting. In the end, I triumphantly gave it a title which contained an information on the amount of traced lines, for example, 187 blue and red metres. In this sense, I thought them to be „final paintings”.[64]

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘139 blue and red’, from the series ‘Ultimate images’, 1979 acrylic, canvas, 55,5 × 60 cm, Leon Wyczółkowski Regional Museum in Bydgoszcz

Artist has also characterized the residue of arbitrariness as „minor incidents of local importance, like delicate waves rippling perpetually smooth Heraclitean River”.[65] These remnants of representation, as artist described them, „small bends or waves appearing at variable frequency spoiled the >>purity<< of flow”.[66] However, Jurkiewicz managed in these works to effectively suppress the painterly dilemma of rationality and spontaneity, if not to solve it. They offered objectivism which sprung from minimalist spirit, factuality of measurement perceived by artist as „the only solution: you trace some metres of line. Blue and red, for example, Maybe more, maybe less. From the line”.[67]

One of Obrazy ostateczne offered 226 metrów białych [226 Metres White] (1979) , with lines running across horizontally oriented square canvas marked with smudges of blue, starting from picture’s left edge, and red, starting from its right edge, gradually transforming into whiteness of central plane. In this work, Jurkiewicz was once more moving towards integration of a line course with background’s plane. This work seems to accumulate artist’s earlier experiences of integrating represented shape with physical groundwork, as well as experiences belonging to artistic traditions which he invoked, namely minimalism in the vein of Stella and Morris. Materiality of lines traced by Jurkiewicz, which seem to tautologically deliver their self-measurements, seems to amplify in Obrazy ostateczne the materiality of painterly groundwork along which they run. Objectivity is here a supplement of the notional order.

4.

Aspiration for establishing art beyond its formal order led Jurkiewicz to extremely reductivist formula of artistic activity subordinate to postulates of transparency and obviousness. Further on, these postulates led him to the discovery of medium of tracing which enabled substituting formal order with a course of the continuous line. Length of this course is defined in maximally strict manner by a formula assumed at the starting point.

Jurkiewicz often repeated that his works originated in the 1970s offer only a kind of a „cold cut” to a viewer. In this period, he postulated exclusion of arbitrariness from art, or irresponsible multiplication of representations, in favour of an inquiry on essential meaning of art (in a specific time of its development), even at the cost of relinquishing its optical dimension. Process of gradual exclusion of traditional arts-related issues from his field of explorations (ca.1967) evokes associations with semantic reductivism of logical positivism school, especially deliberations by Ludwig Wittgenstein which were presented in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921).[68]

Strict and objective character of information relayed through Jurkiewicz’s works, which were formulated by means of media of tracing and photography, shifts his 1970s work far beyond the borders of formal abstraction.

Jurkiewicz seems to relocate to artistic ground Wittgenstein’s adage (fragment of Proposition 7 of his Tractatus), according to whom „Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”.[69] In conceptual phase of his artistic work he declares his interest in „reality of art itself. Mutable, elusive, unpredictable, ever-present. Often reduced to near-zero – present. Very little remains for eyes then”.[70] According to his optics, those artistic achievements which most effectively define meaning of art anew require from the artist a peculiar kind of sensitivity to art’s reality, its flickering, unpredictable and mutable presence. They are equipped with hallmarks of an infallible intution regarding the direction of art’s development, with unprejudiced choice at its basis, a sort of nomination of consecutive manifestation of art which would redefine its meaning. He accepts that genuine artistic discovery „should be a premonition, embracing what future would bring”.[71]

Jurkiewicz associated this kind of intuition, or intensive perception, with an imagination which „should extend our field of comprehending the world. But without resorting to lies”.[72] It is about to enable „projection, externalisation of ideas on nature of visible things”.[73] As early as in his two programmatic texts published in 1967, Wysoko, intensywnie and Manifest, artist opposes production of objects obiedient to minimalist directives of simplicity, with „creativity, the very essence, sole intuition freed from sluggish and stable duration, for which those mute witnesses are being sentenced”.[74] He recommends: „Let us evoke >>manner of being<<, not beings themselves, tendencies instead of facts, that which is necessary – among other possibilities, nodal points – among different stages”.[75] He gives priority to artist’s attitude over work itself, an attitude enabling making an instant and infallible choice of art’s object that would voice its new meaning, „with intense concentration […] and >>soberly<<, with enormous strain”.[76] According to Jurkiewicz, creative act is of lightning-fast, almost momentary, nature. When activity is started, „decision has been ALREADY MADE”, and in its progress

seconds are decisive

this is why I come closer, I ATTUNE with seconds, with seconds passing

„along with seconds passing”

„irreversibly” […][77]

Creative act, which is conceived in this manner, is an impressive attainment of art’s margins. As Jurkiewicz himself expressed it in paradoxical way, reaching the ultimate point is „very center of art ITSELF, it is what’s truly essential”.[78]

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘Messier 46’, 1973 ink, black and white photograph, cardboard, 61,5 × 126,6 cm, Museum of Arts, Łódź

Sanctioning notionally founded intution as art’s peculiar cognitive organ, Jurkiewicz evokes artist’s ethos as a traveller in cosmic space-time which has been already present in the works of earlier modernists. It is no wonder that astronomical objects become in the first half of the 1970s designates of his artistic „silence”. According to his assumptions, choice of both medium and domain of exploration were in this case about to respond to a „total state of art with a maximum of avant garde, specific for a given period”.[79] For this reason, it was supposed to be infallible and bearing the hallmarks of necessity. Artist reminisced on rationale for his decisions for exploring cosmic spaces: „ […] land art? Let there be star and galaxy art! I’ve put brushes away. Now telescope, coupled with photographic camera was my magnificent and surefire tool. Ever-longer exposition of film allowed me to intrude depths of the Universe deeper and deeper”.[80]

Black-and-white photographs, made by means of a telescope he constructed, allowed Jurkiewicz to nominate astronomical objects registered therein to the status of art objects. They also evoke the notion of continuity: shapes visible in photographs register the moment of collision of light rays, emitted by those objects and running across cosmic space, with a photographic film. Representations of single objects – stars, planets, their constellations or nebulae – were grouped by Jurkiewicz on boards executed between 1973 and 1977. They are accompanied by related sections of the sky map, linking representations to designates which were specified in the titles. Several of these works is of systemic character – they mirror the degree of disclosure of cosmic space’s visual richness depending on exposure time. Others expose distance between objects located in different places of the galaxy, and some focus on specific objects, planets or contellations, examining dependence of the character of object’s footage, made from constant observation point, on exposure time.

According to his optics, those artistic achievements which most effectively define meaning of art anew require from the artist a peculiar kind of sensitivity to art’s reality, its flickering, unpredictable and mutable presence. They are equipped with hallmarks of an infallible intution regarding the direction of art’s development, with unprejudiced choice at its basis, a sort of nomination of consecutive manifestation of art which would redefine its meaning. He accepts that genuine artistic discovery „should be a premonition, embracing what future would bring”.

It is interesting to note the imaginative aspect of representations of cosmic space, as proposed by Jurkiewicz. Photograph’s exposure time suggests in them mental travel into far cosmic reaches, optical penetration of its increasingly more remote segments. Jurkiewicz reminisced about them as another chapter in his dialogue with minimalism:

[…] in those time everyone kept mentioning objects. Anyway, I hire giant objects, it seems, like Jupiter, for example. But I don’t trouble myself with anything, I don’t break through anything, I don’t even commission, like Robert Morris did, to make any solid objects. I simply set the telescope up. So Jupiter himself, by the very fact of moving, draws a trace on a photographic film. In other cases, telescope trailed some star, and then it appeared as a point. But Jupiter appears on a photograph as a smudge, as such was the time of its exposure, and finally, you can simply see the Moon and beside it, the tower of St. Adalbert’s church. […] if I point my camera at the sky it is as if I were, depending on amount of exposures, immersing myself in it, deeper and deeper. Short exposure time will only manage to catch me Alpha and Beta of some constellation. But if I set exposure at ten minutes, more of them will appear, until a moment when whole frame will become star-studded.[81]

Strict and objective character of information relayed through Jurkiewicz’s works, which were formulated by means of media of tracing and photography, shifts his 1970s work far beyond the borders of formal abstraction. This group of objective astronomical communication could also include photographically recorded projection of the image of the Sun on the wall of an apartment, obtained by means of a telescope (Słońce 1 VII 1972, 1972) [Sun 1 VII 1972]. According to Jurkiewicz, these works respond to the need of a „new support, new point of reference”. He adds: „such is the range of penetration, infinitely vast, heavy, concrete, silent and… unattainable. As a stone, as perfect silence. As a trace of galaxy on a film”.[82]

Language becomes most convenient tool for transmitting this type of objective information. As a medium, it has already been positively sanctioned in, previously mentioned, work Kształt ciągłości: „krzesło” – „krzesło”krzesło ‒ krzesło. Linguistic sings, encrusted in this work into a continuous horizontal straight line, connecting spatialized sign of the chair with its designate, correspond with concept of intensive perception, interweaving sensual and intellectual elements with each other, which Jurkiewicz professed. Manner of reception implied in Krzesła is a sort of fusion of an act of perception and interpretation of signs. Logical consequence of this mode of comprehending linguistic signs is an inclination for emancipating linguistic expressions from visual elements, which has been repeatedly manifested in Jurkiewicz’s work. Significative equivalence of linguistic expressions and their designates has already been announced in Białe czyste cienkie płótno, which originated not long before.

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘White, thin, clean canvas’ (artwork documentation), 1970 canvas, gouache, ink, 120 × 200 cm, the artist’s archive

In other works, manner of using language gets radicalized: linguistic expressions function in them independently of their designates. List of astronomical objects, captioned as Twenty Three Stars for Steve [Dwadzieścia trzy gwiazdy dla Steve’a] (1973?) and written in machine script, is an example of such work. It groups alphabetical star names, beginning with letter S, apparently in reference to the first name of work’s addressee.[83] Considering affective aspect of the dedication inscribed into a title, this enumeration of astronomical objects is presented to the reader in the form of a rudimentary poem.

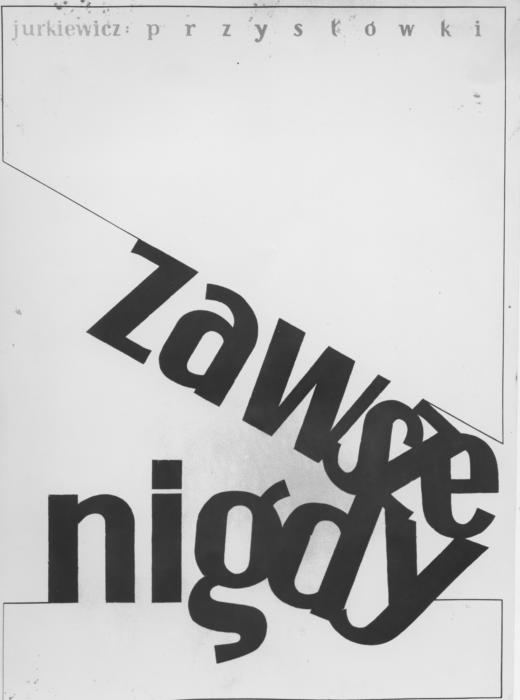

Jurkiewicz’s textual work Przysłówki [Adverbs], reproduction of which with an accompanying commentary has been included in the catalogue of an exhibition Sztuka pojęciowa [Notional Art] (1970), also can be perceived as a one-verse poem. Words written next to each other – „zawsze, nigdy, ponad wszystko, jedynie, wyłącznie” [„always, never, above all, solely, exclusively”] – do not refer to specific designates, concrete or abstract. Rather, they connote sphere of qualitative classifications concerning processes or things. These expressions are not general concepts. They can be taken as a set of partial definitional expressions of the notion of necessity. Isolated from their proper significative contexts and placed in an image field, they pronounce the meaning of the notion of continuity, on the basis of the qualification of the necessity of an artistic choice based on sensitive anticipation, which Jurkiewicz postulated. They constitute a subsequent form of continuity.

Choice of linguistic expressions and the manner of using them strictly corresponds to specific character of Jurkiewicz’s practice which favoured such factors as attitude over concretization of artistic idea, state of potentiality and careful anticipation of consecutive manifestations of art. Enumeration of stars and listing of adverbs serve as allusions to states of continuity. Jurkiewicz wrote on the second of the discussed works: „I have consciously used adverbs instead of words that could create e.g. manifesto >>for reading<<. I have chosen several common adverbs without resorting to e.g. rolling dice – again, it would be a portrayal of certain mathematical idea”.[84] These works are not designed solely for reading or watching. For the artist, „confrontation of data” was the most important, a kind of semantic short circuit resulting from introducing words into the domain of visuality.

However, in some of the text works Jurkiewicz makes use of the visual aspect of linguistic signs, associating his own artistic output with the domain of visual poetry. Change of reciprocal placement of two letter sequences, making up title words visible on two boards of Przysłówki „zawsze” „nigdy” [Adverbs „always” „never”] (ca. 1970) extends range of associations that these words generate with erotic connotations, it enhances the notion of continuity with an affective factor. Representation of these two words in loving embrace suggests interchangeability of their meanings. Jurkiewicz’s other works from this group are of programmatic character: letter shapes making up word „sto” [„hundred”], visible over square-shaped underlining in work Sztuka rzeczywista: 100 metrów [Real art: 100 Metres] (1971) self-reflexively define length of lines they are built of.

Objective character of art’s reality is announced by a kind of a visual poem entitled 50 x the very art [Sama sztuka 50 x] (undated), where ten verses composed of, unspaced and pyramidally narrowed upwards (similarly to certain painterly compositions consisting of blue and red stripes), inscriptions of title expression „theveryart” create a kind of crater-like cavity at the top of the text. In this cavity, respective letters elude linear order of the inscription. Their chaotic placement brings associations with the domain of micro-particles described by physics’ principle of uncertainty.[85] As Jurkiewicz suggests, art itself turns red-hot in the domain of elementary particles, beyond the field of defined form, as much instisting on viewer’s sensual perception, as on his intellectual insight. Jurkiewicz wrote on the process of reception of his works:

Certain signals flowing from the side of „realization” are to inform the viewer immediately and directly, in the manner appropriate to our receptors, while other moments of realization are designed to effectively intervene into our impressions and thoughts, transferring and subjecting whole observational material to reflection of intellect.[86]

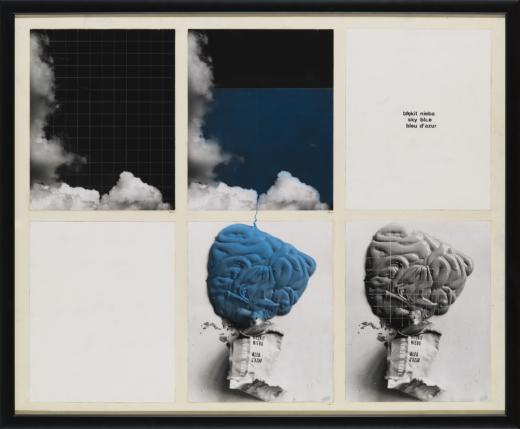

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘Błękit nieba’ / ‘Sky Blue’ / ‘Bleu d’azur’, 1973 black and white and colour photograph, paper, 66 × 82 cm, Museum of Arts, Łódź

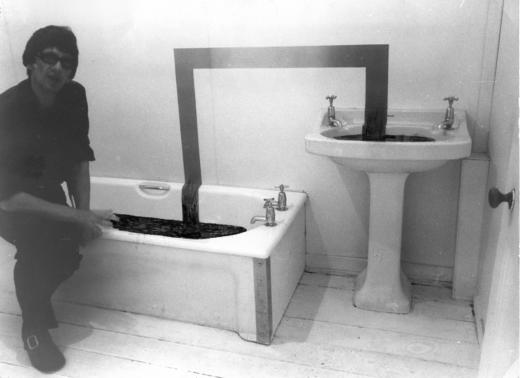

However in Jurkiewicz’s 1970s work, words are most often positioned in a situation of tension versus images. Diversity of these relations is shown in works made by means of photography. Besides references of tautological nature (in photographic version of Białe czyste cienkie płótno and in two versions of Błękit nieba [Sky Blue] (1973) where words constitute a notional equivalent of what is being presented in work’s visual component, these works situate linguistic expression as a carrier of objective information on artifacts. It happens both in works concerning astronomical objects, and in staged events. Among works belonging to the latter group, it’s worth focusing on the series of black-and-white photographs making up artistic communique entitled Łazienka [Bathroom] (1972).

These photographs depict the process of blurring of geometrical form, painted in a thick line and bent at the right angle in several points, on bathroom walls and outer/inner surfaces of bathtub, by stream of water flowing into bathtub. Ends of line traced with a black ink and located inside the bathtub, became gradually blurred, causing water to get coloured as its level grew. As artist himself described this work: „water filling bathtub […], reaches geometrical outline and dissolves, showing distinctive residue at the bottom, shapeless silhouette which is self-drawn, being a sort of completion of this geometry”.[87]

Photography is employed in Łazienka as a tool to annihilate form. It seems to favour process over geometrical order. Similar to the case of Environment, it shifts viewer’s attention from the sphere of everyday existence to the domain of spontaneous interactions between particles of matter, demanding cognitive intuition to be activated. Situation staged in an installation Łazienka (Jurkiewicz realized it twice: in 1971 during exhibition Atelier ’72 in Edinburgh, and in an exhibition Refleksja konceptualna w sztuce polskiej. Doświadczenia dyskursu 1965-1975, in 1999) was the reference to the process registered in a series of photographs under discussion. In this version, rainbow-coloured band, oil-painted on canvas, mixes water coloured with red pigment in a washbasin with blue pigment-coloured water in a bathtub.

After photographic versions of works Białe czyste płótno and Kształt ciągłości: „krzesło” – „krzesło”krzesło – krzesło, another attempt at integrating sign with photographic representation is a work entitled Omega. Na ścianie, płótnie i sztaludze [Omega. On Wall, Canvas and a Frame] (1971). This series of photographs reveals the principle of producing planar illusion (consistent with surface of photographic print) of a view of capital letter “O” (in reference to title word “Omega”), rotated around its axis by 90 degrees: this view consists of shapes (perceived from an appropriate point of view), painted on studio wall, easel, and white canvas placed on it. Photographs test the accuracy of a view of letter shape, which approximates square. Some of them reveal inconsistency of letter view in an incorrect setting of the lens of photographic camera, or simulate the blending of black clothed figure of an artist in the continuity of the letter shape at correct setting. In this work, artist himself becomes the part of the shape of continuity (its closed circuit brings to mind paintings from Continua series), in tune with his postulate of preeminence of artistic attitude over its materialization in specific work.

Crisis started about 1980. I’ve considered all attempts at crossing the line of the final images as misguided. So-called composing and formal enhancement was below their dignity level. Further simplification led to almost unnoticeable differences, to stubborn and impotent formalism.

Jurkiewicz manifested his interest in the possibilities of manipulating photographic image. He realized several works which called into question photography’s claim for objectivism, its ability of conveying the true image of reality. His consideration of the photographic medium fits into trend for testing the properties of photographic representation which manifested in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and was exemplified by various kinds of revisions of foreshortening undertaken by, among others, Jan Dibbets and Mel Bochner. In opposition to these practices, Jurkiewicz often amplified in his works capability of a photographic image for deceiving viewer’s eyesight. In a series of photographs making up work entitled Samolot (fałszywa dokumentacja) [Airplane: False Documentation] (1971), he offers shots of a modern jet plane flying over Wrocław landscape, while in reality object visible in the photographs is a jet model, hung on a piece of string in artist’s studio window. Sequence of photographs included in the work Incydent [Incident] (1970) shows the same model in consecutive scenes of burning, nosediving and final explosion. At closer inspection, flashes seen in the photographs are reflections of light pointed at ready prints, which were re-photographed with the same lighting setup.

In an accompanying commentary, Jurkiewicz defines the subject of Incydent as “false event”. He declares that up until this moment, “dispassionate relationship showed new horizons”.[88] Elsewhere, he defines his trick photos as creating “art out of mistakes”.[89] Artist has also been examining the possibility of eyesight deception by photographic image in activities focused on obtaining continuous record on a photographic negative of a moving light dot, among others in a series of photographs entitled Rysowanie światłem [Drawing With Light] (1978).

These operations on the reality of the photographic medium lead Jurkiewicz, it seems, to a new mode of understanding relationships between language and photography, or putting it broader, between work’s verbal and visual component. They prove that it is possible for the photographic image to dodge language’s codifying procedures and, what’s more, that the former is able to endow work’s verbal component with semantic tones that were unforeseeable at the point of departure. This possibility is already announced in a photographic supplement to work Białe czyste płótno, which consists of four staged photographs made with the participation of a naked female model wrapped in a title fabric. These photographs endow title expression with lyrical, almost intimate, connotations. It turns out that only language can codify photographic image, but that also photography can exert its influence on semantic range of linguistic expression, confer metaphorical character upon it. Jurkiewicz explored this possibility in later poetic works which originated since the end of the 1970s and referred to his chosen photographic images, and sometimes paintings as well.

Let us briefly describe biographical background of Zdzisław Jurkiewicz’s poetic turn. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he was confronted with a kind of creative impasse resulting from consistent compliance with the postulates of transparency and obviousness of artistic expression. Normative aspect of Obrazy ostateczne based on strengthening them by establishing proportions between rational components, or foreseeable parameters of employed construction formula, and spontaneous components, slipping an element of arbitrariness into the work. Jurkiewicz wondered: “maybe something unnamed and boundless was left in those >>waves<< and line bendings?”[90] He also explained that

Crisis started about 1980. I’ve considered all attempts at crossing the line of the final images as misguided. So-called composing and formal enhancement was below their dignity level. Further simplification led to almost unnoticeable differences, to stubborn and impotent formalism.[91]

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, ‘Drawing in the bathroom’, 1971 black and white photograph, paper, the artist’s archive

Jurkiewicz exposes his doubt in the legitimacy of tendency for purifying image from all anecdotal and emotional content, which haunted him in that period. After all, formalism was for him exactly the sort of creativity trap which he tried to avoid in his work as a principle. Expansion of discursive space for creative activities turned out to be essential in that moment. This mode of expansion would allow restitution of work’s content, while simultaneously being in tune with artist’s concept of creativity as an attitude of being attentive to facts of art which reality offered. As Jurkiewicz explains:

For many reasons, it couldn’t be painting or visual arts any longer. It could be poetry only as a totally different realm of expression. It couldn’t be even prose. Since, although it’s not easy to put it precisely, I still owed so much to minimal art’s lesson. So, I was able to track myself down in poetry, and I believe I’ve contained many of my unsaid infatuations in this, not very commonplace, form.[92]

Poetic turn heralds Jurkiewicz’s entrance into the post-conceptual phase of his creative work. However, his poems retain many conditions which very decisive for the nature of his earlier solutions: according to Jurkiewicz, synthetic character of poetic phrase has to be consistent with the typically minimalist principle of economy of means. Moreover, tension between work’s visual and verbal component, which has been launched in his conceptual works, is kept intact. Many of his poems offer an analysis of ephemeral meanings noticed by their author in photographic images.[93] However, these meanings are of strictly private nature, so it seems justified to associate them with an element of “third meaning” (complementary against primary meaning, or denotation, and ideologically coded connotation) explored by Roland Barthes in photographic representations and film stills.[94]

Likewise, Jurkiewicz’s poems transmit the meaning of experiencing continuity which author perceived in confrontation with multiplicity and diversity of everyday experiences: listening to music, visitation by an insect flying through an open window, dream scenes, or momentary intellectual illuminations concerned, for example, with discovery of 80 divided by 81 as an exemplification of the notion of continuity (in number which is the sum of this division specific numeric sequence is infinitely repeated).[95] Such experiences could also include moments of anticipation of events, unfulfilled intentions of acts of intense expectation.

Jurkiewicz’s poems, collected in a book Tylko, jedynie, zawsze [Only, Solely, Always] (1997)[96], present whole range of nuanced states of a lyrical subject, from lack of faith in the sense of artistic explorations, in a heavy atmosphere of early 1980’s „poor” period, to condensed experiences of internal integration. Many of them describe delight resulting from miraculous encounters which evoke associations with André Breton’s surrealist confrontations with objects of desire which are detached from everyday reality’s order. Motif of encounters of this type, evoking associations of Jurkiewicz’s work with found object tradition, has already been present in his Manifesto of 1967, where he wrote that it is artistically necessary „TO MARK EVERYTHING: /floor, table, canvas, bottle, air, clock, bird… / these would be TRACES OF OUR EXISTENCE AS CREATORS, THE VERY MANIFESTATION OF CREATIVE PRESENCE, PERSISTENTLY INTERFERING PRESENCE”.[97] Poetic dimension of a decision to include life’s facts in the artistic domain are developed in wordings from the text Sztuka w poszukiwaniu istotnego (1970). As artist wrote:

[…] Event of personal life, „burdened” by the climate of intimacy, can also be a field of interest (material). This case seems to me to be even more interesting, as harder to carry out. After all, I would not like to present so-called destructive guts. It is not all about any passionate and loudmouthed expression, I live it to agitators.[98]

Miraculous events described in Jurkiewicz’s poems also come from „the immense”, from the domain of glimmering and variable art’s reality. These confrontations are of erotic nature, which is suggested by travesty of a piece of Breton’s poem quoted by Jurkiewicz in the following wording: „there’s nothing I love more than the sight of the immense which eye cannot fully cover”. As a response, artist has proposed his own version of the piece:

there’s nothing I love more

than the sight of the immense

which your eyes

cannot

cover.[99]

Jurkiewicz’s poems are often commentaries on author’s own theoretical assumptions. They estimate their effectiveness, amplify appropriate meaning, develop, and harmonize with the rhetorics of earlier theoretical statements on creativity. Above all, they construct discursive context of his artistic output, more extensive than the one built in earlier, much more concise, theoretical statements. Peculiarity of this space seems to be defined by two synonymical sequences:

- Immensity – continuity – present time, corresponding to objective reality of art, and

- Imagination – love – intensivity, which corresponds to subjective order of perception.

These orders are not strictly disjunctive in relation to each other. Creative subject is the factor which weaves them together: space explorer which takes his flight in intense concentration

Right in the target

Into the very center

of rapid horizon[100]

5.