This article is an attempt to interpret the 1990s Ukrainian art through the lens of feminist and gender themes. This text examines the role and place of a woman on the artistic scene of the time. It is also an attempt to answer the following questions: How did the female and male images change? What was considered intimate and erotic? What artistic manifestations could be considered feminist? Why was not clearly articulated feminism manifested in the Ukrainian art in the early 1990s? Also, why does the oeuvre of Ukrainian women artists remain little known to researchers even now?

[wps_products title=”Postmedium” show_quantity_label=”false” hide_quantity=”true” full_width=”false” link_to=”shopify” link_target=”_blank”]

If every cook must learn how to govern the country, according to Vladimir Lenin’s famous dictum, then every woman is granted a position in power structures.[1] This phantom position of the female manager was pictured by Kharkiv artist Sergei Bratkov in his 1985 collage series Vira Frantsivna Ivanova — an Ordinary Soviet Woman. The artist used the average woman’s image from the Soviet magazine Rabotnitsa and inserted a regular female worker into the political elite, placing her picture alongside portraits of the General Secretary and members of his governing apparatus. In this way, the author created a fantasy visual construct where a woman occupied the central place in the political life of the USSR. In the opinion of Ukrainian literary critic Solomiia Pavlychko, the ambivalent attitude and interpretation of the female role in political and social life was a defining feature ofdefined the turn of the 1980s period.[2] She described social developments of the early 1990s as the “stage of the shock of freedom”.[3] Pavlychko explained that the cultural vacuum was replaced, on the one hand, by a recovered and revitalized national mentality with elements of rural culture, and on the other, by the assimilation of Western cultural manifestations of freedom in the form of beauty pageants, popularity of plastic fashion, dumbing down of the public mind through TV soap operas, and the emergence of pornography as a category of female beauty.[4]

Artist Viktoria Parkhomenko was closely associated with the modeling industry. At the same time, she created critical artistic projects in which she conceptualized the woman’s place and role in society. Together with Natalia Radovinska, she created an installation made of stencil photo collages, entitled For Those Who Can Knit (1992), in which the artists depicted each other as characters featured in Soviet women’s magazines. The artists accompanied their own portraits with a sarcastic text that reproduced the ideological excess of the Soviet glossy press, ridiculed it, and problematized politically driven attempts to impose the Soviet female ideal even after the collapse of the USSR.

The artists, who were active in the early 1990s, were squeezed between the old system that was already barely functioning and the newly created “clan system” of the artistic scene, which artist Oksana Chepelyk describes in her interviews.[5] According to her, women artists either joined some isolated community, found themselves on the periphery if they created social-critical art which was unpopular at the time[6], or established close connections between their practice of arts and work in related fields, which literally influenced the artists’ choice of themes and aesthetics, with such fields including theater, teaching, architecture, illustration, and literature.[7] For example, Valeria Troubina from Kyiv created scenery and costumes for performances of the Lesia Ukrainka National Academic Theater of Russian Drama, Iryna Nirod from Lviv constructed scenic compositions in her easel works and worked at a theater, while Larysa Rezun-Zvezdochetova from Odesa used a theatrical wing flat as a module symbol in her art.[8]

Most artists found no problem with the contemporary social system, which used patriarchal models in a new way. Economic problems and the daily need to feed their own families were experienced by women far more acutely than patriarchal patterns. As for the themes that we can now subject to feminist or gender-based interpretation, they appear in particular in the oeuvre of artists who were only indirectly connected to the artistic establishment of the time. This group included Yana Bystrova, Tetiana Hershuni, Vesela Naidenova, Viktoria Parkhomenko, Maryna Skugarieva, Valeria Troubina, and Oksana Chepelyk, among others.[9]

THE NEW WOMAN’S METAL DRESS

Along with a socio-economic collapse, the 1990s were marked by the emergence of a new mass culture, which relied on media clichés and was characterized by an increased interest in fashion, popular Western culture, and sex. Kyiv-based artist Oksana Chepelyk was among creators who methodically studied gender issues and the role and status of women in the post-Soviet society. Her installation-performance The Birth of Venus (1995) was both embedded in the then fashion industry and criticized it.[10] In the work, half naked model performers strolled down the catwalk with shell-like polyethylene inflatable structures behind their backs: the artist alluded to the classic Venus story in this spectacular fashion.[11] According to Chepelyk, this approach communicated a social tendency of those years when a woman worked hard to pretend to be a fragile and an unburdened “goddess,” and the shell behind her back embodied the “home,” which she “carried on her back” without noticing it, when she performed the ostensibly natural and almost imperceptible female role in society.

[wps_products tag=”postmedium” show_quantity_label=”false” hide_quantity=”true” full_width=”false” link_to=”shopify” link_target=”_blank”]

With the onset of the 1990s, the economic crisis and new market conditions permitted an avalanche of cheap and substandard goods in the Ukrainian market. Along with flashy textiles, the demand for second-hand culture had risen greatly. Clothing came to Ukraine as humanitarian aid from abroad (popularly known as humanitarka) but entered the retail network and became the base for a kind of private business.[12]

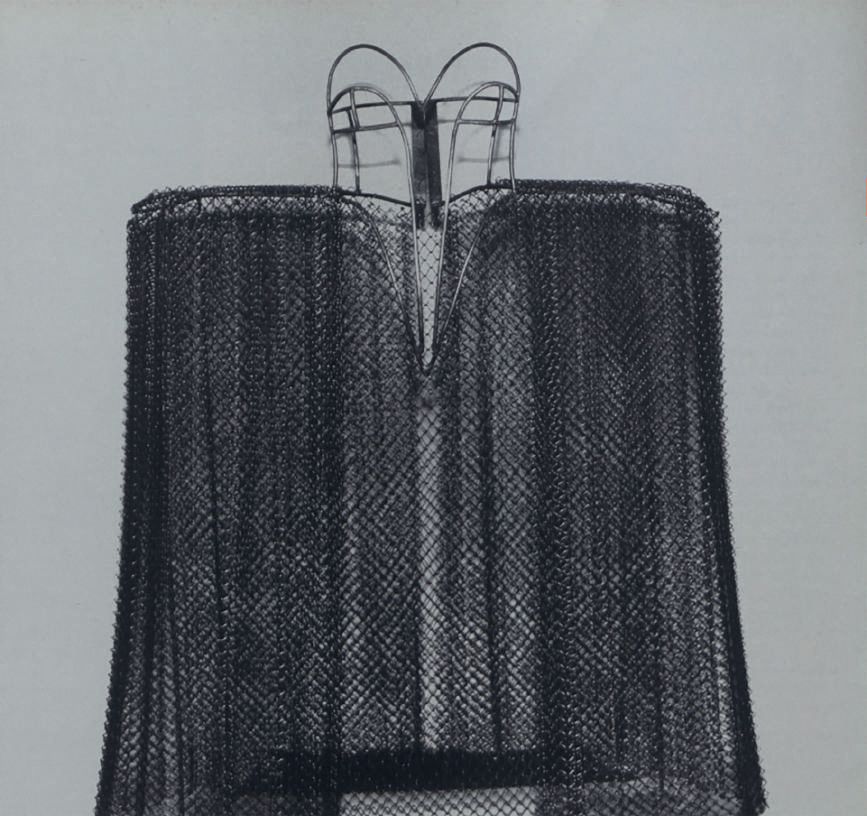

Iryna Lastovkina, ‘Madame Butterfly (Untitled)’, 1995, metal object. Page from ‘The Two Sides’ catalog

Fashion had quickly become one of the instruments of body objectification in society, a cover that imposed on the woman the category of sexuality as an indicator of attractiveness in the man’s eyes.[13] Almost simultaneously, Oksana Chepelyk and Iryna Lastovkina created similar works of art, featuring framed women’s dresses made of metal, which could be seen as a uniform, or a kind of social cage in which the woman existed.[14] Created for The Mouth of Medusa exhibition (1995), focused on the inability of women to find creative fulfillment, the work of Lastovkina elevated women’s ambitions as a dream about a dress. Over time, this work has become a visualization of ephemeral disorientation which characterized the system of values of that time, although the artist juxtaposed women’s fragility with a metal rigid frame in this work.[15] Madame Butterfly became Lastovkina’s last work in the contemporary art field. The artist’s sudden exit from experimental art was in no way caused by criticism or rejection of this work, as Lastovkina, on the contrary, received approving reviews from the artistic community. However, the creator opted for a stable income as an educator and restorer, which allowed her to contribute to the family budget and to support her artist husband in his subsequent practice of art.[16]

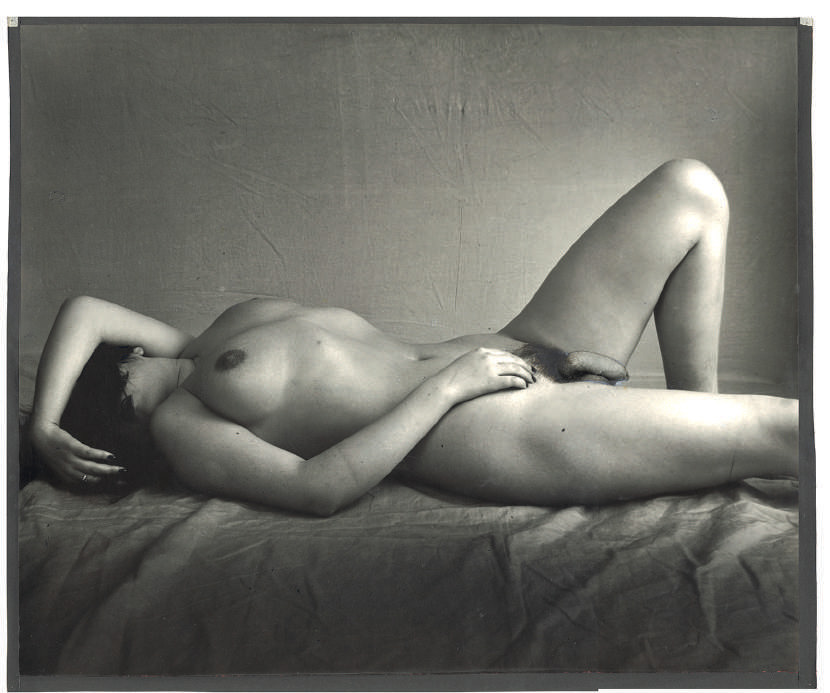

In Lastovkina’s story, we can discern the overall trend of that period, which concerned not only the creators mentioned in this article but also those who never returned to their practice of art. Catastrophic economic circumstances shaped a new type of woman who single-handedly assumed the responsibility for providing for the financial well-being of her family, often neglecting her own self-realization, and, at the same time, combining stereotyped male and female social roles.[17] Such post-Soviet reality, which became a distorting mirror of the ideas of equality and gender balance, was highlighted by Kharkiv photographer Serhii Solonsky in a series of photos entitled Boudoir (1997) , which depicts nude young women having both male and female genitalia.[18] The modern viewer may mistakenly associate the Boudoir imagery with the ideas of transgenderness, which had not yet been manifested in the post-Soviet space. In addition, the global feminist practice of the time actively instrumentalized the image of a phallus to denote masculinity and used it as a symbol of the patriarchal tradition. For example, a programmatic feminist work by the American artist Lynda Benglis’s showed the artist as a nude shorthaired woman posing with a double dildo butting against her pubis. This photograph was featured as an advertisement in the November 1974 issue of Artforum. Solonsky’s idea for Boudoir was to position it as a sneak peek into the emergence of a symbolically and socially new kind of human, a woman who, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and throughout the capitalist 1990s, proved to be more adaptive and motivated to survive than men.[19] Benglis and Solonsky used a shared conceptual apparatus for the artistic field, constructing an imaginary body in similar ways, but the context and the underlying idea significantly differentiated their works.

Serhii Solonsky, from the ‘Boudoir’ series, 1997, silver-gelatin print, collage. Photo courtesy of the the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography (MOKSOP)

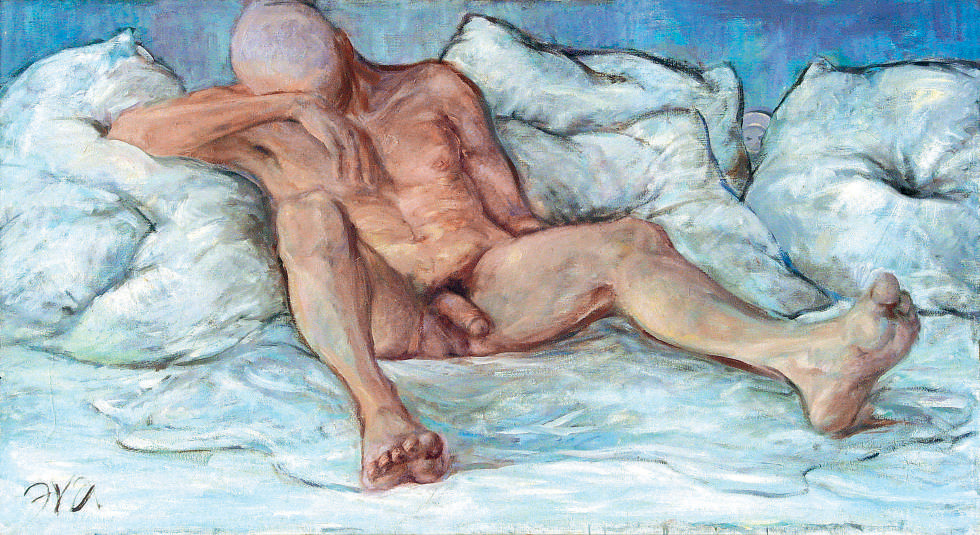

Tetiana Hershuni, part of the diptych ‘A Tribute to Pasolini’, 1992, oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of the Berezhnytsky collection

In contrast to Solonsky’s Boudoir, Tetiana Hershuni, the artist from Kyiv, portrayed a naked and faceless male body. In the picturesque diptych A Tribute to Pasolini (1992), Hershuni (currently known as Taia Galagan), the central figure is a naked man lying in bed. On one part of the diptych, we see the faceless character reading a book while lying under the covers. On the other, the same naked character is shown leaning on his knee, with his head bowed, legs wide open and his penis shown in minute detail. Meanwhile, in the Soviet painting canon, the bed was an intimate space, and thus not to be revealed. Working with forbidden images was very much in tune with the artist’s simultaneous departure from academic painting. Both parts of the diptych are sentimental and sensual in nature. The painter imparts to the man some traits that can usually be seen in the art when creating poetic and objectified female images. Hershuni’s character acquired the traits of weakness, tenderness, sentimentality, femininity, and even obedience. Thus, the creator depicted him not at all as men used to see and position themselves. This diptych cannot in any way be construed as an act of aggressive objectification of a man by a woman, or a sitter by an artist. In Hershuni’s work, nudity is first and foremost an embodiment of the private as opposed to the public. Misinterpretation of the work by our contemporaries is fleetingly raising a deeper, theoretical, and even ethical research of the present-day re-reading of artworks that make up the corpus of Ukrainian art. Art historian Jürgen Harten rightly noted in his article on the Soviet/post-Soviet transition zone in the article Eight Stamps in the Passport… that “the problem is how far we are ready and able, when interpreting certain sign systems, to use such systems’ own contexts as our starting point before opting to compare them with each other instead.”[20] After all, there is a clear danger that in the process of rethinking the unwritten history of Ukrainian art, we will go beyond the limits set by the idea of the artwork and come to the point of creating misinterpretations and distorting the historiographic data in general.

For example, in her analysis of Ukrainian art, Oksana Briukhovetska makes an attempt to re-read certain works through the feminist lens and sees the first attempts to subvert canonical masculinity in tutu-wearing half-naked sailors, shown in the video Voices of Love (1994), filmed by Arsen Savadov and Georhii Senchenko.[21] Such an approach does exist, but new interpretations often conflict with the context of the authors’ work and practice. The curator Marta Kuzma interpreted this work as feminist, in her annotation to the exhibition.[22] However, the masculinity in the video is also a representation of the Soviet totalitarian system. Tutus are an allusion to the post-Soviet viewer’s perception of the Swan Lake ballet as a tool of media silencing in cases of political collapse, and the grotesqueness of the whole show is intended to provoke a sense of the absurdity of the historical moment in general. Therefore, if we go beyond political connotation, this work can hardly be seen as related to feminist themes and gender manifestations in art, even though it displays highly typical formal traits of these topics.

(UN)CONSCIOUS FEMINISM

The feminist paradigm of the 1990s gravitated toward the ideas of Ukrainian modernism. Solomiia Pavlychko saw Ukrainian intellectual thought of the turn of the 19th century, which was already imbued with ideas of equality and emancipation, as the key to interpreting this complex and ambiguous period. Natalia Filonenko, who curated The Mouth of Medusa exhibition in 1995, also turned to the memories of the last pre-revolutionary feminist events of 1916 for her concept of the exhibition.[23] It emphasized the seventy-year ideological gap in the continuity of feminist thought and the difference between interpretations of the “pre-revolutionary” and the “independence-era” feminism in Ukraine.[24] Forgotten or hidden Ukrainian feminist thought returned to independent Ukrainian culture not only through the corpus of specialized literature but first of all by means of materializing the image of an emancipated woman.

For an example of this actual situation, we can turn to a fragment of Ilya Chichkan’s installation A Milk Portion for Working in Hazardous Conditions.[25] A men’s jacket depicted the cult figure of Kyiv’s art scene in the 1990s, the American art critic and curator Marta Kuzma, who served as director of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Kyiv. Chichkan’s project dealt with the topic of work in totalitarian societies, and, in particular,with women working as seamstresses. A Milk Portion for Working in Hazardous Conditions project consisted of dresses emblazoned with portraits of Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin. The artist sewed himself women’s jackets, as well as two men’s jackets, with photo prints portraying the artist Tetiana Hershuni, wearing a headscarf and humbly bent over the sewing machine, and Marta Kuzma. The image of Kuzma was distinctive not only due to its formal traits. The artist himself wore the jacket emblazoned with Kuzma’s face, giving the project a performative component, which added a symbolic “look from the margins” to the perception of Kuzma’s image. His action became “the creator’s metaphor for the assertively-independent image of the American woman as opposed to the Soviet post traditional oppression of women through labor.”[26] Shaped by a society that cultivated the ideas of gender equality and self-realization, Kuzma had at her disposal a qualitatively different conceptual and professional apparatus. It allowed her to almost single-handedly influence and determine the development of the progressive Ukrainian art in Kyiv of the 1990s and to bring the practice of many artists closer to subjects which were akin to those present in the Western context. For example, in the project A Milk Portion for Working in Hazardous Conditions, Chichkan did not turn to the problem of cultivating fashion, because he himself was an epigone of fashion and used it as a tool of artistic expression. However, Kuzma’s explication of his project positions this work as feminist, thus placing a certain social-critical focus alien to the artists’ own thinking at the time.[27]

Ilya Chichkan, fragment of ‘A Milk Portion for Working in Hazardous Conditions’ installation, 1996. Photo by Yevhenii Nikiforov. Photo courtesy of the press service of the Mystetskyi Arsenal National Art and Culture Museum Complex and the Collection of Borys Hryniov and Tetiana Hryniova

The importance of Kuzma’s study of the Ukrainian feminist discourse goes beyond her outlook, professional beliefs, and her overall biography as an example of an emancipated Ukrainian woman who introduces new ideas from abroad and presents their very embodiment. Kuzma’s systematic curatorial and artistic work in the field of the formation of Ukrainian socially critical art and the elaboration of feminist themes in the 1990s is very important. She directly participated in Kyiv’s first independence-era feminist exhibitions; in particular, she organized Diane Newmeyer’s photography exhibition The Breasts of the Subway (1994) and supported the collective exhibition The Mouth of Medusa (1995).[28]

Kuzma’s equals in their level of professional activity and active social position included Solomiia Pavlychko in literary studies and journalism and Oksana Zabuzhko in literature. Odesa-based Uta Kilter was another prominent figure of the art scene at that time. Acting as a TV presenter, performer, philosopher, actress, and art critic, Kilter is the embodiment of the multidimensional modern individual, having influenced the development of political performance and regional activism and made a name in cinematography and television journalism of the period.

The Uta Situation program, produced by her jointly with Viktor Maliarenko for the Odesa TV company ART between 1992 and the early 2000s, not only reported news about Ukrainian art practices and events, but also actively covered the cultural life of European countries.[29] The Uta Situation featured an uncommonly authoritative, subjective, and non-trivial outlook of culture. The producers made it as a series of short documentaries serving public informational and educational purposes, which actually amounted to creating a corpus of video art that had its dedicated regional audience for more than a decade. The special character of this TV project, its unique editing practices and storylines make The Uta Situation akin to TV and video experimental productions released in the United States during the 1970s and 1980s, including Lisa Bear’s Communications Update (1979), Cast Iron TV (1983), and Paper Tiger Television (1981). In addition to TV, Uta Kilter extensively worked with bodily performance practices and was one of only a handful of Ukrainian artists to work with the body as an instrument of artistic expression in the 1990s. Kilter’s artistic and TV practice can be defined as a life-long artistic project, similar to ever-changing cultural activism.

BODY INDEPENDENT: OBJECTIFIED OR REVEALED?

The cultural and public perception of body image was influenced by the delayed wave of the sexual revolution that entered the post-Soviet space. Nudity was equated then with the ideas of openness and freedom, and pornography and eroticism were identified with sexual appeal, independence, and radicalism. Riding on this wave, the media market produced a demand for commercial (advertising) photography, which used precisely erotic images.

Photographer Mykola Trokh problematized the issue in his art manifesto as follows: “Many of my colleagues, having smelled money, have rushed into advertising photography. It not only creates a distorted, fictional, and illusory picture of the world but also involves an element of fascism and discrimination directed against those whose shape does not meet the standards of top models. If I am aware of this, I have to create anti-advertising photography, to do my best to truthfully capture reality in its nonheroic, non-flashy manifestations, and portray ordinary people, if you will.”[30]

The glossy “Western” model of feminine beauty, copied by Ukrainian advertisers, was strikingly different from the reality of the post-Soviet 1990s. Trokh explores this cultural contrast in his photographic series Schoolgirls (1993). The author portrayed aged women dressed in schoolgirl uniforms and with faces hidden by porcelain doll masks. In one of the photos, the character masturbates with her legs spread. The photographer emphasizes this deviant image of schoolgirls also because schoolgirls became an erotic fetish in the late Soviet time and were associated with free sexuality and the rebellion. When seen on adult women, the school uniform created a grotesque association, revealed an attempt to be sexy nymphets from fashionable magazine covers, even though post-Soviet women could not be such nymphets by definition.

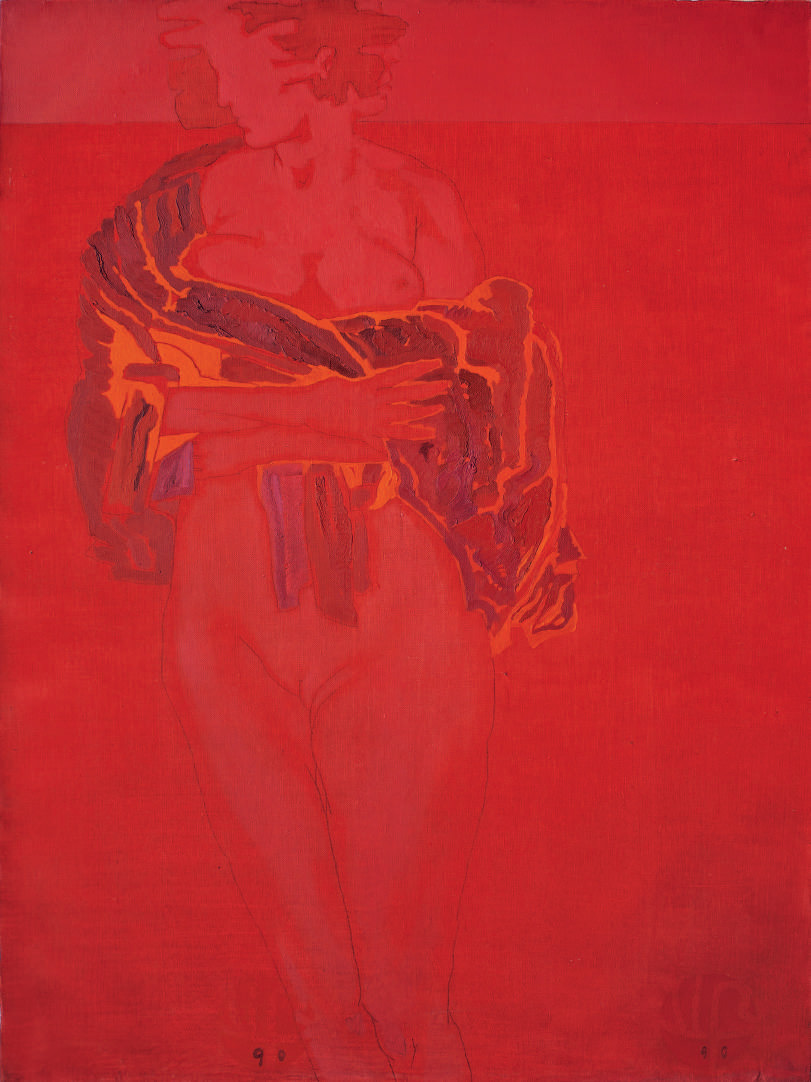

Yana Bystrova, ‘Only the Healthy Will Survive, 1990, from ‘The Red Series’, oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist

According to art historian Tetiana Zhmurko, Trokh avoided both male and female bodies in his oeuvre. His cross-cutting theme was the naked body in photography, which he interpreted as a collective, public body. And with photographic certainty, he portrayed it as subject to decomposing in the excessively artificial pornographic environment. For Trokh, pornography became an artistic language and a tool of ideological expression.[31]

In contrast to the “male outlook,” women artists depicted their own bodies with the help of other formal means of artistic expression. They perceived the body primarily as a collection of human qualities, emotions and personal experiences contained in a certain bodily form. For example, in Yana Bystrova’s picturesque Red Series (1989–1991), the traumatic story of the artist’s separation from her partner was represented through half-naked female bodies. Full-bosomed women with disproportionate body parts visualized the experienced internal fractures. Bystrova painted her female artist friends and almost dissolved them in the totally red background of the painting. With these “therapeutic artworks,” the artist turned to universal values and, probably, went beyond the focal limits of feminist or gender themes in art. At the same time, the artist Maryna Skugarieva used the image of a lyrical female body as the old European tradition in art, and complemented painting with handmade embroidery when creating her pictures.[32] The existing clichés on the so-called women’s art accumulate in the author’s practice: women depict women by using a “feminine material,” that is, cloth. However, in the series Good Housewives (1997–2010), the artist portrays mostly nude women against the background of messages from women’s online forums, which include, along with discussions of domestic violence and psychological conflicts, comments from participants of cooking and fashion forums. The curious and, at the same time, routine perspectives of Skugarieva’s characters, of different age and appearance, form a virtual gallery of housewives as a new social group, which became clearly defined in Ukrainian society in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Nudity was not provocative in the art of the 1990s. The excess corporeality in culture became a counter-reaction to decades of Soviet bans and taboos against it. Corporeality became material for research, it acquired the personality and humanity of its own. Artists used nudity as a metaphor for freedom, defenselessness, or a human lacking stereotypes or ideologies. Given the complex political, social, and cultural situation, individuality and private space were the important values acquired in the post-Soviet era. Instead of radical slogans and feminist art manifestos, Ukrainian artists opted for a therapeutic escape. And the ideological struggle focused not on the gender issue, but on the right to individuality, the embodiment of the private and intimate as opposed to the public and official.

Jo Anna Isaak notes that it is not in the slightest the so-called “inner essence” of the woman, but rather her place and role in society that lead to the identification of the feminine with the reactionary.[33] The same tendency was observed by Solomiia Pavlychko, who emphasized that the painful adaptation of feminist ideas in independent Ukraine was caused by the aggressive and reactionary Western feminist movement of the 1970s. With this feminism, Ukrainian populists “intimidated” the electorate in order to preserve the familiar and comfortable image of womanhood.[34] Pavlychko described in detail the problem of forgetting one’s own cultural context due to the interpretations of feminism which were ideologically distorted in the Soviet era and misleading in the 1990s. This was the actual reason for the rejection, or rather, the banal ignorance of their own historical past by Ukrainian women, even though that past involved far deeper roots of feminism in Ukraine than it may seem today. In the absence of sound theoretical knowledge on the issue among the general population, it was precisely professional opinion, authoritative criticism, and personal examples set by cultural activists that shaped the artistic and social manifestations of feminist art in Ukraine in the 1990s. In agreement with philosopher Tamara Zlobina’s statement of the need to re-read Ukrainian art, researcher Oksana Briukhovetska adds that such a problem is not exclusive to Ukraine and offers an example from the Polish art scene: “It was feminist art criticism that helped some of them [Polish women artists] to realize the feminist nature of their own works. This phenomenon can be called unconscious or intuitive feminism, which can then be re-articulated into a conscious one.”[35]

The most important problem for us now is not the lack of bright and iconic women artists in the 1990s, because they were obviously there, but rather the scattered nature of information about the 1990s, the lack of public archives and a museum of contemporary art in Ukraine. It is important to reconsider the practice of the creators active in that period, to take into account prevalent socio-political conditions in order to broaden the context and to properly outline the emergence of certain ideas in the Ukrainian society. We have no intention whatsoever to limit the list of artists of the 1990s to those represented in this text. We merely outline the topics most often manifested in artistic practices at that time and set a vector for the study of Ukrainian art through feminist optics.

Art historian Nadiia Pryhodych identified video Bloody Mary, filmed in 1999 by Natalia Holiborda, Ivan Tsiupka, and Solomiia Savchuk, as a “feminist paraphrase of the Hong Kong action film.”[36] A rooftop shoot-out involving three women is played out in front of the viewer. Between the shots, the characters discuss chicken cooking techniques, intimate details of their private lives, and everyday events. This work may be appropriately seen not only as an imitation of a crime film, which was popular in the 1990s but also as an expression of hidden misogyny. However, it is equally important to interpret this image from the psychoanalytic perspective, where all three heroines are treated as embodiments of the same woman. In addition to the social conflict of self-identification in the 1990s, the filmmakers revealed the psychological drama of a woman at the dawn of the 21st century, which came as a result of the gender confusion marking the end of the 20th century.

The essay is published on the occasion of Polish translation of the book Why there are great female artists in Ukrainian art. The Polish version was published by the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation in cooperation with the Ukrainian Institute. The book was prepared and first published by the PinchukArtCenter Research Platform in 2019.

[1] But, as we know from the history of the Soviet era, women only ever occupied niche humanitarian sectors and never became full-fledged members of the USSR’s senior management layer in charge of strategic positions. See more here: Ayvazova, Svetlana. “Sovetskiy variant ‘gosudarstvennogo feminizma’” [The Soviet Version of “State Feminism”] // Gendernoye ravenstvo v kontekste prav cheloveka [Gender Equality in the Context of Human Rights]. – Retrieved from: http://www.owl.ru/win/books/gender/11.htm [In Russian]

[2] See more here: Tolstoy, Ivan; Gavrilov, Andrey. “Zhenshchina kak inakomysliye” [The Woman as Dissent] // Radio Svoboda. – December 17, 2017. – Retrieved from: https://www.svoboda.org/a/28925140.html [In Russian]

[3] Pavlychko, Solomiia. “Feminizm yak mozhlyvyi pidkhid do analizu ukraiinskoii kultury” [Feminism as a Possible Approach to the Analysis of Ukrainian Culture] / Feminizm [Feminism] (A collection of articles, ed. by Vira Ageyeva). – Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo Solomiii Pavlychko “Osnovy,” 2002. – P. 30-31. [In Ukrainian]

[4] Pavlychko, Solomiia. “Posttotalitarna kultura yak nosii znevahy do zhinok” [Post-Totalitarian Culture as a Carrier of Contempt for Women] / Feminizm [Feminism] (A collection of articles, ed. by Vira Ageyeva). – Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo Solomiii Pavlychko “Osnovy,” 2002. – P. 63-64. [In Ukrainian]

[5] Hleba, Halyna. “Oksana Chepelyk: Ya rozpochala feministychnu abo gendernu temu zadovho do…” [Oksana Chepelyk: I Started Working on the Feminist or Gender Theme Long Before…] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – December 11, 2018.– Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/ua/woman-in-culture/oksana-chepelik-feminizm-gender.html [In Ukrainian]

[6] Hleba, Halyna. Oksana Chepelyk: Ya rozpochala feministychnu abo gendernu temu zadovho do… [Oksana Chepelyk: I Started Working on the Feminist or Gender Theme Long Before…] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – December 11, 2018.– Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/ua/woman-in-culture/oksana-chepelik-feminizm-gender.html [In Ukrainian]

[7] Iakovlenko, Kateryna. “‘Telo’ Parizhskoy Kommuny. Chast pervaya” [The “Body” in the Art of Paryzkoii Komuny Street Group. Part One] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – March 7, 2017.– Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/en/context/telo-parizhskoj-kommuny-part-one.html [In Russian]; Hleba, Halyna. “Oksana Chepelyk: Ya rozpochala feministychnu abo gendernu temu zadovho do…” [Oksana Chepelyk: I Started Working on the Feminist or Gender Theme Long Before…] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – December 11, 2018.– Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/ua/woman-in-culture/oksana-chepelik-feminizm-gender.html [In Ukrainian]

[8] More details on Iryna Nirod’s work for theater are available here: Bichuia, Nina. “Iryna Nirod. Kreidiane kolo doli” [Iryna Nirod. The Chalk Circle of Destiny] // PROSTSENIUM. – 2006. – No. 2-3 (15-16). – P. 66-74. – Retrieved from: http://old.kultart.lnu.edu.ua/Proscaenium/prostsenium%20new/%D0%92%D0%B8%D0%BF%D1%83%D1%81%D0%BA%202-3(15-16)2006/Nirod.pdf [In Ukrainian]; Rezun-Zvezdochetova’s installation Those Wounded in the Heart (1990–1991) that used a theatrical wing flatwas displayed at international exhibitions in Venice and Berlin.

[9] Zvizhynsky, Anatolii. “Fantaziii ta demony Vesely Naidenovoii” [Fantasies and Demons of Vesela Naidenova] // ZBRUC [Electronic source]. – June 18, 2013.– Retrieved from: https://zbruc.eu/node/8960 [In Ukrainian]

[10] The Birth of Venus performance is part of Oksana Chepelyk’s early performance cycle Mysteries of Moving Objects, united by the theme of discovering the woman’s place in the post-Soviet society.

[11] The artist turned for inspiration to Sandro Botticelli’s work The Birth of Venus (1484–1486), illustrating the ancient Greek myth about the birth of the goddess Venus (Aphrodite in Greek) from sea foam.

[12] More details are available here: Platonova, Anastasiia. “Odezhda umirayet posledney: Zoya Zvinyatskovskaya o chetverti veka ukrainskoy mody” [Clothing Is the Last To Die: Zoya Zvinyatskovskaya on a Quarter of a Century of Ukrainian fashion] // PLATFOR.MA [Electronic source]. – July 13, 2017.– Retrieved from: https://platfor.ma/magazine/text-sq/projects/in-progress-moda/ [In Russian]

[13] Hleba, Halyna. “Oksana Chepelyk: Ya rozpochala feministychnu abo gendernu temu zadovho do…” [Oksana Chepelyk: I Started Working on the Feminist or Gender Theme Long Before…] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – December 11, 2018.– Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/ua/woman-in-culture/oksana-chepelik-feminizm-gender.html [In Ukrainian]

[14] Iryna Lastovkina, Madame Butterfly installation (1995); Oksana Chepelyk, installation-performance Clothing as a Hiding Place (1996) from the cycle Mysteries of Moving Objects.

[15] Iakovlenko, Kateryna. “Irina Lastovkina: Kogda my uvideli ukrainskuyu zhivopis, u nas vsyo perevernulos s nog na golovu” [Iryna Lastovkina: When We Saw Ukrainian Painting, Everything Turned Upside Down Inside Us] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – December 14, 2018. – Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/ua/woman-in-culture/irina-lastovkina-kogda-my-uvideli-ukrainskuju-zhivopis-u-nas-vseperevernulos-s-nog-na-golovu.html [In Russian]

[16] Ibid.

[17] This inversion of gender roles in the social system of Ukraine in the 1990s was similar to the premise of the feminist science fiction literary genre, which focuses on an imagined society without gender stereotypes. However, the Ukrainian situation was a deviant manifestation of social roles being swapped.

[18] Solonsky’s 1995 series Boudoir includes about ten photographs created in the technique of analog photomontage.

[19] Serhii Solonsky’s personal communication to Halyna Hleba.

[20] Harten, Jürgen. “Vosem pechatey v pasporte, ili ‘Tam chudesa, tam leshiy brodit…’” [Eight Stamps in the Passport or “What Wonders There! There Goblins Scurry…”] // Sovetskoye iskusstvo okolo 1990 goda [Soviet Art about 1990]. – P. 8. [In Russian]

[21] More details are available here: Schiller, Valeria. “Ekho lyubvi” [The Echo of Love] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – November 20, 2018. – Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/en/context/eho-ljubvi-savadov-senchenko.html [In Russian] Briukhovetska, Oksana. “Obraz zhertvy i emansypatsiia. Narys pro ukrainsku art-stsenu i feminism” [The Victim Image and Emancipation. An Essay on the Ukrainian Art Scene and Feminism] // Prostory [Electronic source]. – March 3, 2017. – Retrieved from: http://prostory.net.ua/en/krytyka/139-obraz-zhertvy-i-emansypatsiia-narys-pro-ukrainsku-art-stsenu-i-feminizm [In Ukrainian]

[22] More details are available here: Schiller, Valeria. Ekho lyubvi [The Echo of Love] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – November 20, 2018. – Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/en/context/eho-ljubvi-savadov-senchenko.html [In Russian]

[23] Iakovlenko, Kateryna. “‘Rot Meduzy’: pershi sproby feministychnykh vystavok” [“The Mouth of Medusa”: The First Attemps at Feminist Exhibitions] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – November 9, 2018. – Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/en/context/rot-meduzy-pershi-sproby-feministichnyh-vistavok.html [In Ukrainian]

[24] These terms denote the period before the October Revolution of 1917 and one that began with Ukraine gaining its independence in 1991.

[25] A textile jacket with a female photographic portrait on the back was part of Ilya Chichkan’s installation A Milk Portion for Working in Hazardous Conditions, presented at the 1996 S.o Paulo Biennale.

[26] Kostiantyn Doroshenko’s personal communication to Halyna Hleba.

[27] Kuzma, Marta. “Textual explication of Ilya Chichkan’s project A Milk Portion for Working in Hazardous Conditions for the 1996 S.o Paulo Biennale”. – Retrieved from: http://www.23bienal.org.br/paises/ppua.htm?fbclid=IwAR0BIu6nK6vKQZDgdQ_b87lC2X0cEkptSnvdYGwPqzuzxZvonBtC1xtsg [In Ukrainian]

[28] Iakovlenko, Kateryna. “‘Rot Meduzy’: pershi sproby feministychnykh vystavok” [“The Mouth of Medusa”: The First Attempts at Feminist Exhibitions] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – November 9, 2018. – Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/en/context/rot-meduzy-pershi-sproby-feministichnyh-vistavok.html [In Ukrainian]

[29] Briukhovetska, Oksana. “Uta Kilter: ‘Ya maiu vadu – fiziolohichno ne mozhu brekhaty’” [Uta Kilter: “I Have a Flaw – I Physiologically Cannot Lie”] // KORYDOR [Electronic source]. – March 14, 2018. – Retrieved from: http://www.korydor.in.ua/en/opinions/uta-kil-ter-ya-mayuvadu-fiziologichno-ne-mozhu-brehati.html [In Ukrainian]

[30] Trokh, Mykola. “Chast vtoraya ‘Manifest’” [Part Two “Manifesto”] // NASH [Electronic source]. – July 19, 2019. – Retrieved from: http://nashizdat.com/blog/photo/25.html [In Russian]

[31] Zhmurko, Tetiana. “Mutiruyushchiye 90-ye Nikolaya Trokha” [Mykola Trokh’s Mutating 1990s] // Bird in Flight [Electronic source].– November 1, 2018. – Retrieved from: https://birdinflight.com/pochemu_eto_shedevr/20181101-nick-troh.html [In Russian]

[32] Martyniuk, Olena. Solovei i troianda [A Nightingale and a Rose] (A catalog of artist Maryna Skugarieva’s works) // Art-Agent, 2009. – P. 6. [In Ukrainian]

[33] Isaak, Jo Anna. “The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Laughter” // Feminism and Contemporary Art: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Laughter. – London, New York: Routledge, 1996. – P. 11-46.

[34] Pavlychko, Solomiia. “Does Ukrainian Literary Studies Need a Feminist School?” / Feminizm [Feminism] (A collection of articles, ed. by Vira Ageyeva). – Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo Solomiii Pavlychko “Osnovy,” 2002. – P. 21. [In Ukrainian]

[35] Briukhovetska, Oksana. “Obraz zhertvy i emansypatsiia. Narys pro ukrainsky art-stsenu i feminism” [The Victim Image and Emancipation. An Essay on the Ukrainian Art Scene and Feminism] // Prostory [Electronic source]. – March 3, 2017. – Retrieved from: http://prostory.net.ua/en/krytyka/139-obraz-zhertvy-i-emansypatsiia-narys-pro-ukrainsku-art-stsenu-i-feminizm [In Ukrainian]

[36] Pryhodych, Nadiia. “Svoyo kino” [Cinema of Our Own] // Khudozhestvenny zhurnal. – 2001. – No. 30-31. – 2001. – Retrieved from: http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/80/article/1758?fbclid=IwAR1fp1WqckKHbrgDXOe9nHhAHZ0vk6JocYFCaq0u40D4wwm5KeJustrnk8w [In Russian]

Imprint

| Index |