Adam Przywara: Dismantling the exhibition order proposed here in the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, let’s begin with the series of paintings of Tirana’s “Boulevard of Heroes” — what made you depict the place and how does the political history of Albania resound in these spaces?

Edi Hila: Looking at this series, you must understand that in Albanian reality you cannot remain indifferent to what is happening around you. You can’t just be an observer to all the events happening. Through subsequent crises and abrupt changes, politics become a fuel of public life in the whole country. Dynamics of political events for some time now set a particular rhythm of life for every inhabitant. At the same time, I must point out that in my paintings I do not aim to represent politics or political events. My paintings are not political, that’s not the point of them. My intention is just to paint certain themes and objects appearing in my surroundings. The decision on what to paint arises from the feeling that, as a painter, I can’t be indifferent to what I see, of what what happens around on an everyday basis. I’ve always been trying to work on topics that are significant and complex, looking for the sites which encapsulate all the characteristic features of Albanian modernity.

AP: So your paintings observe your surrounding reality?

EH: This often happens very randomly, on the basis of daily encounters. Certain objects or views clearly stand out from the everydayness. They are characterised by certain aesthetic paradox. They exist visibly in places where we could never imagine them. A good example is the painting “Under The Hot Sun”, used on the cover of the exhibition catalog. One summer day, I visited the beach and the whole scene was just waiting for me there. People were lying on the sand, sunbathing or hiding under summer umbrellas; next to them concrete bunkers from the times of war were emerging out of the ground; and on the horizon was a huge abandoned industrial ship. And although such a scenography seems to be full of internal conflicts, it existed there on that day when I saw it. Another example is the work titled “On the Street – Carousel”, which is not present in the exhibition, but which has been reprinted in the catalog. The picture shows a merry-go-round designed for small children, which was set right next to a very busy street in Tirana. Such views are very memorable and come back to me when I paint. Most importantly, they have to materialise tensions, reveal certain paradoxes.

AP: Let’s come back to the works opening in exhibition, particularly the triptych “People of the Future” from the series “Migrations”. Painting it you referred to the history of the financial crisis in Albania, which started with the collapse of financial pyramids schemes in 1997. One of the effects of the crisis was a tragic mass migration on Italian ships like the famous “Vlora”. However in your paintings we see only the back of this ship, like it could be viewed by an observer who was left behind on the coast. And that was actually your personal perspective. You never boarded that ship, migrated, before or after the fall of communism. Why did you decide to remain in Albania?

EH: Of course I was not watching these events indifferently. Back then, I was thinking a lot about the possibility that we could live somewhere else together with my wife and daughter. However, our decision to stay was determined by circumstances outside of our control, namely a situation with my parents. They were very old then and wouldn’t be able to set off with us. They needed my help, so it was absolutely natural for me that I couldn’t leave them. I had to stay. If, however, I was in a different situation, yes, I would gladly use this opportunity. I’m quite sure that it is of fundamental importance for the artist’s life to encounter new stimuli and contacts which travels can easily provide. If I could experience migration, maybe even just brief departure, I would probably see some things a little more vividly, or perhaps just in a more mature way. Perhaps such a situation would be beneficial. But as we all know, it is not possible to walk all the different ways life can provide us with. At the same time, if I had left in the 1990s, I would have likely lost my connection with my Albanian reality. From the outside, from a distance, one is unable to read what is going on in a direct way. You are unable to understand the complexities and fragility of local contexts. The fact of staying in one place allowed me to enrich my art with the topics that I discovered, and with the specific aesthetics that I have developed as a result.

I think that staying in the country played an important role in the process of seeking the truth of my expression. The pursuit of artistic truth is fundamental to my painting practice. The truth, understood as presenting a reality of my surroundings as they exist, is far more important for me than any notion of beauty. The beauty of painting is an outcome of a truth emerging from the relation between what is existing in reality, and what is depicted in my painting.

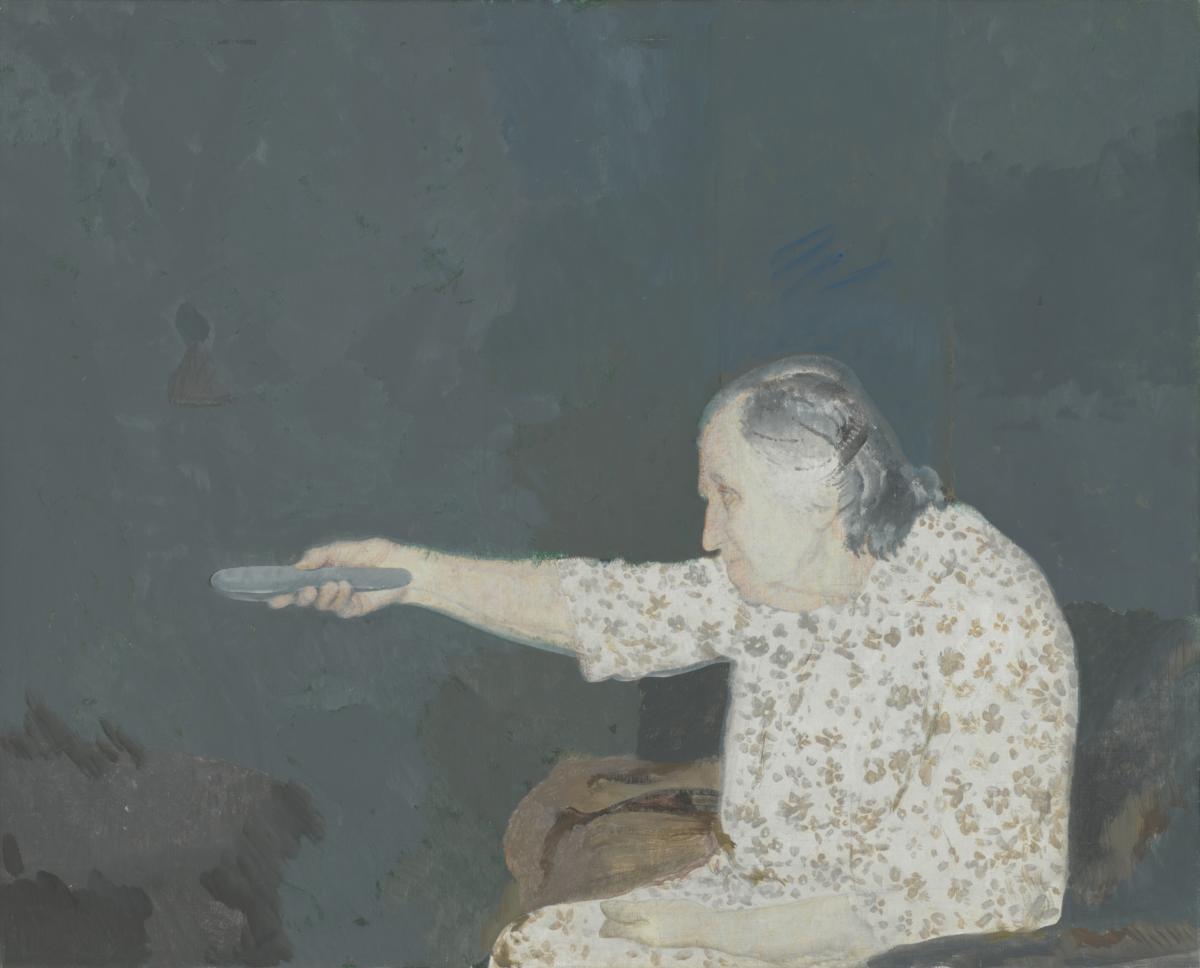

AP: Looking at paintings such as “Mother” from the series “Hommage and Image”, I’m left with the impression that a crucial source of truthful imaginary for you is family and close relations with others. And as you mentioned it was your family that made you stay in Albania. I would like to untangle this relationship between what we can understand as familiar and/or local, and in a certain way its opposite — the political and the public. It seems your paintings balance and intersect freely between these two spheres of reality?

EH: Yes, in relation to this painting, it is necessary to emphasise its double reading. On the one hand, this is of course a sentimental portrait of my mother who, at that time hardly left home because of a prolonged illness. This element of sentimental truth is obviously visible. On the other hand, I’m involved in a more aesthetic dispute, or rather, a philosophical one. It refers to the discussion that took place at the beginning of the century in academia and concerned the theory of representation proposed in the philosophy of Jean Baudrillard. We can therefore read this work as a representation of a woman who moves between images, trying to move from a painting image to another reality, reality of the screen.

AP: On the same exhibition wall, we encounter a series of paintings entitled “Tent on the Roof of a Car” created more recently. In these paintings, again, your individual history is intertwined with that of society and politics on an international scale. Some of them depict journeys which you and your wife did in Albania by a car with a tent mounted on the roof. Others relate to spaces defined by the temporality of the tent itself; associated with contemporary migrations. Am I right to say that here again the family-society duality plays a crucial role?

EH: Yes, as with the image of my mother, this series of tents is based on a double reading, as you mentioned. The history of these paintings began quite accidentally. I wanted to spend my holidays with my family and purchased a tent. Later, this tent began to interest me as an object. It started combining with other elements present in the whole series. I painted, reading reports of wars in the Middle East, and watching wave of migrants from Syria and North Africa arriving in Europe, particularly in Athens. I remember back then it was perceived as an open door to the entire continent. In this context, I began to read about tents, explore the topic of this structure, with all its history and genealogy. It made me realize clearly how the tent is such an old and fundamental object of our everyday life. Thinking about the tent as a building, I realized its archetypal qualities for any built environment. The gesture of putting it on the roof of the car, in turn, made the tent, a symbol of architecture, closely combined with something symbolically modern and technological. In this connection, opposing phenomena, like settling and migration, could be combined together. Simplicity and comprehensiveness of such merging was attractive for me. And, not only for me as far as I remember: in 1921 Le Corbusier in his book “Towards a New Architecture” compared the beauty of the Parthenon to the beauty of a car.

In my understanding architecture is an expression of society, its mentality, ways of living, and finally the tastes of certain groups in it. Observing the architecture of particular country, one can say a lot about its society.

AP: The design of the exhibition consists of four monumental walls about 9 meters high, with a wooden structure coated with white translucent material. It brings to my mind temporary constructions, exactly like a tent. As this is the first exhibition of such scale in your career, it’s a good moment to ask — how do you perceive architectural scenery in your paintings?

EH: First of all, I must underline that the idea for the set design was not mine. It was discussed between curators and the architect of the exhibition. How the paintings were arranged in space, indicates only their perspective towards my work. I see it in a completely different way. I do not exclude, of course, that there is a connection between the idea of the tent we discussed, and the materiality of the exhibitions architecture. Perhaps such a connection exists. From what I could understand, in the opinion of the curators, this choice of exhibition design resulted from a need to counterbalance my classical imaginary with a more modern, synthetic matter.

AP: Most of your works, if not all, have a visible architectural or spatial dimension. Sometimes the built environment constitutes only a background, other times it becomes the only subject. What does architecture mean for your practice as a painter?

EH: In my understanding architecture is an expression of society, its mentality, ways of living, and finally the tastes of certain groups in it. Observing the architecture of particular country, one can say a lot about its society. Through architecture, we can try to build our understanding of it. You can observe a good example of this in my series “Penthouses”. In it, I decided to focus on buildings of Albanian nouveau riche, people who enriched themselves during their emigration and returned to the country building new homes. Usually in order to build them they invested into roof-additions on the top of existing buildings in the city. Studying them, I was looking for common aesthetic denominators. In many cases, one particular type of roof was repeated: in the design of windows there was a tendency to use arches; usually large balconies and spiral staircases were present. Simultaneously, during my life, I have traveled all over Albania, always documenting the buildings encountered along my way. Reflecting on the subject of the penthouses, I returned to my photographs. In the context of these particular group of people who got rich very recently, the structures they erected became a strong expression of their non-defined position in the society, an enactment of it. In this way, they became protagonists of a newly establish identity, which was strongly associated with these structures added on the roofs of old buildings. When looking at my photographs, I started associating these new buildings with the traditional settlements in the Albanian mountains. People who lived there developed specific way of building their houses which is called “Kullë” in Albanian. This traditional defensive architecture, from Ottoman times, produces houses which resemble towers. Some of them are really thin — 4 by 4 meters in the base and going vertically up. In my series “penthouses”, I decided to combine these defensive houses located in the mountains with luxurious roof-additions built in the cities. In this way, I tried to emphasize the isolationist aspect inscribed into these penthouses. Building on the top of existing houses, far away from street level, can be read as an expression of fear from others. In this sense, it is a new dimension of the same defensive architecture which we know from the Albanian mountains. In the phenomenon of penthouses, one can also see metaphors that potentially describe a broader psychology of the region in which there have always been local and internal fights and conflicts. These paintings can point toward tensions related to racism, class conflict and much more. I am not sure if I’m able to verbalise all the elements and meanings in this this complex entanglement, but I hope you appreciate my effort.

Imprint

| Artist | Edi Hila |

| Exhibition | Painter of transformation |

| Place / venue | Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw |

| Dates | March 2 – May 6, 2018 |

| Curated by | Kathrin Rhomberg, Erzen Shkololli, Joanna Mytkowska |

| Photos | Bartosz Stawiarski |

| Website | artmuseum.pl/en |

| Index | Adam Przywara Edi Hila Erzen Shkololli Joanna Mytkowska Kathrin Rhomberg Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw |