Even though it would have been logical, nothing noteworthy happened in the 1990s in Poland with respect to museums, mostly due to a lack of funding. The first main milestone, however, was not until 2004, coincidently the year Poland joined the European Union (EU). Soon afterward, money could be obtained from different EU funding bodies. However, historical problems soon emerged due to a struggle for power and control over the narrative of Polish history. Contradicting postures formed. Above all, a movement aiming to strengthen national unity was gaining steam that attempted to use culture as a means of fortifying a political agenda.

The first truly modern museum built in Poland is the Warsaw Uprising Museum. This museum serves as a model while also functioning as a reference point. Similarly, one can look at the House of Terror Museum in Budapest. Prior to its construction, the subject of a museum dedicated to the Warsaw Uprising was taboo during Communist times. However, a monument was erected during the thaw, after 1956, dedicated as a memorial to Warsaw’s heroes, but without any specific reference to the uprising itself. After 1989 and the Solidarity movement, a state of emergency overshadowed discussions about constructing a museum dedicated to the uprising. Accordingly, only a small collection of objects from the Historical Museum of Warsaw, together with relics obtained from the relatives of veterans, existed.

It is, however, surprising that a museum of the uprising was not established immediately after 1989. Pawel Ukielski, director of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, explains that in the 1990s, history and the past were not considered important, everyone wanted to focus on the present and the future. During this period, no new institutions were established. Comparatively, in Hungary, the House of Terror Museum was completed in 2002. By the 2000s, politicians in Poland soon realized that they could again resume talk about building the museum.

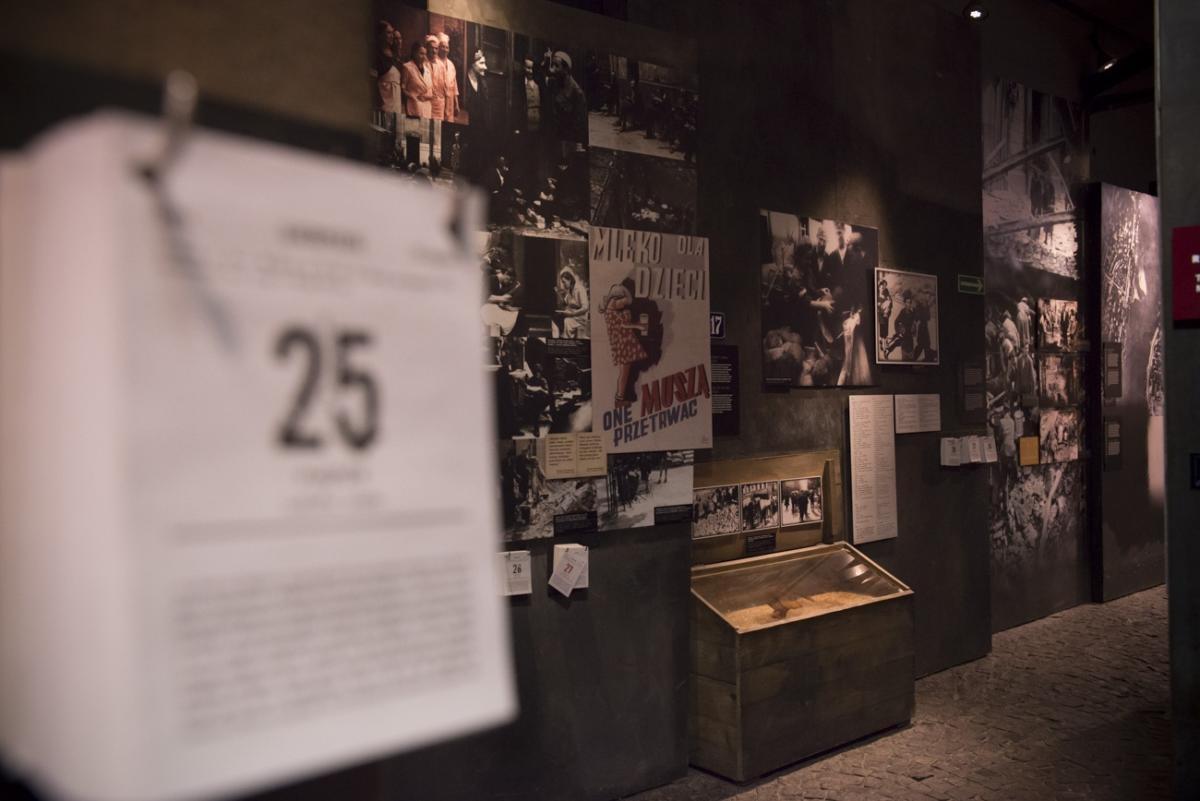

An exhibition organized to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the uprising in 2004 serves as a case in point. The exhibition was based on constructing a patriotic national myth of Polishness, with the aim of strengthening and disseminating this myth to a broad public. Organizers carefully constructed the exhibition to be entertaining. However, critics complained of noise pollution and movement in the exhibition. These criticisms were right. Comparatively, one can look at the Esztergom Castle Museum and Hungarian National Museum, where extremely boring exhibitions are displayed that lack stimuli and adequate contextual information.

In addition, the Warsaw Uprising Museum fails to take into account the introduction of debate, ongoing since the uprising, as to whether or not it was even a good idea to resist. The Warsaw Uprising is of monumental significance to modern Polish history. Over 85% of the city was destroyed (including many of its inhabitants). According to Ukielski, Director of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, one of the biggest challenges he has faced is how to present these debates within museological terms. He emphasized that he did not want to create a “museum of debate” adding that he did not want to answer the question whether the uprising was worth it or not. He also said that they organized numerous public discussions about the topic.

According to Joanna Wawrzyniak, a sociologist, historical dilemmas should be given more presence in the exhibition. However, it would be hard to adapt it to the myth of creation. The exhibition focuses on a heroic battle, the “great national adventure.” At the entrance, in the children’s activity section – a room of little rebels – kids can learn about the war. In this interpretation, heroism, self-sacrifice, and patriotic fighting come to the fore. Wawrzyniak is not sure, however, that this is an appropriate message to pass on to the youth.

The reception of the Warsaw Uprising Museum shows aptly how museums maintain an influence that can shape public opinion. Maria Kobielska, a professor in the Department of Anthropology of Literature and Cultural Research at Jagellonian University, argues that if young Poles were asked about the most important event of Polish history during WW2, 90% of them would mention the Warsaw Uprising. However, this has not always been the case: around the 50th anniversary of the uprising, many articles were published suggesting that the youth were interested in the uprising. The situation has radically changed over the past 10 years, and the Warsaw Uprising Museum has played a significant part.

Another example is the Museum of the History of Polish Jews (POLIN), inaugurated in 2014. According to Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Program Director of the institution, while there are numerous Holocaust museums in Poland, the POLIN – which is the Hebrew translation of Poland – wishes to display the centuries of Polish-Jewish coexistence. The exhibition presents the war period by showing the history of the Warsaw Ghetto, and only mentions the places in the countryside that trigger debates up until now, i.e., instances of Polish people participating in the killing Jewish people. Post-war anti-Semitism and pogroms are discussed in more detail. In connection with this, Wawrzyniak states with a slight cynicism that this happened this way because it can be blamed on Communism. POLIN received the European Museum of the Year Award in 2016, obviously the result of compromises, but altogether a great success and huge professional accomplishment. Naturally, there is a different situation in Poland, there are different circumstances, but I cannot help remembering the House of Fates in Budapest, standing empty for two and a half years. It was supposed to be a Holocaust-memorial but the huge project was led by a controversial historian, therefore was attacked by historians and Hungarian Jewish organizations, also. Though the construction has been ready for two and a half years the building remains completely empty, it wasn’t inaugurated, and there are no exhibitions within it.

Compared to the previous two, a much smaller but for the Poles a much more important institution was opened two years ago: the Katyń Museum, a failed project. The biggest problem with the Katyń Museum is that it does not even try to make the events understandable for outsiders, no background information is presented. In addition – solely out of the museums I have been to – most of the texts are only in Polish, and the English audioguide is rather uninformative.

The creation history of the museum might serve partly as an explanation. The permanent exhibition has not been organized for “outsiders”: relatives, descendants of those executed in Katyń had been longing for an appropriate memorial for years. The objects displayed in the glass cases were found at the excavation of the mass graves. After fifty years of lies, the excavations had huge importance and received many reactions, during which it became clear that the murders were committed by the Soviet army. During Communism – even though no one believed it – the propaganda kept repeating that it was a crime committed by the Germans. In 2010, another layer was added to the history of Katyń when the airplane of the Polish delegation arriving for the 70th anniversary commemoration crashed. This tragedy overshadowed the mass murder of Katyń.

According to Kobielska, a Polish identity pattern can be noticed in today’s Katyń remembrance: the heroic role of the victim, or rather the martyr. Martyr is the symbol of purity and innocence; it is not a human being. In contemporary Polish culture (movies, literary works) there is no such text that deviates from this even the slightest. In this regard, talking about Katyń’s interpretation, the topic is still a taboo. The deceased of Katyń are the emblematic figures of this martyrdom and perfect purity.

The most recent large-scale exhibition is the Museum of the Second World War, which opened in 2017 in Gdansk. No heroes, heroic figures are displayed here, but simple, everyday people. And step by step it becomes evident that in the war everyone is a victim, no matter which side they are on. The exhibition presents with such systematic thoroughness different micro histories of the worldwide catastrophe – known and unknown ones, as well – which are usually invisible for many aspects of history: a room that had the greatest influence on me. The tribulations of the children torn from their parents lives of millions of Soviet soldiers, the horrific suffering of Stalingrad’s citizens, the story of the Poles dragged to forced labor in Germany camps during the war are shown through upsetting life stories. Stages of the seemingly endless suffering are depicted through actual human fates. If someone is susceptible to this, they can spend days in the exhibition’s spaces without being bored even for a second. The show is filled with an amazing amount of scientifically proven and easily understandable material, complete with professional technical background.

The most recent large-scale exhibition is the Museum of the Second World War, which opened in 2017 in Gdansk. No heroes, heroic figures are displayed here, but simple, everyday people. And step by step it becomes evident that in the war everyone is a victim, no matter which side they are on.

The next big event will be the inauguration of the Polish History Museum next year. The institution has been in the works since 2006, but without its own museum building. It is obvious to ask whose history will the permanent exhibition show – the concept of which is 90% done. Robert Kostro, Director of the museum, demonstrates the difficulties with the following example: in the 19th century Poland did not exist, but the Poles did, and not only in the once Polish territories, but because political emigration was significant. On the other hand, for a long time, the country did not only stand for Polish people but also Lithuanian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Jewish people, many ethnicities and religions.

Kostro added that in Polish traditions there are two concepts of nations living side by side. One connects the nation to the country, marked by the name of Józef Pilsudsk, and the other one is connected to 19th century national democrats, and means ethnical-cultural uniformity: for them being Polish first and foremost means being Catholic. This latter approach is a rather closed one. Kostro believes that it is not the duty of the museum to judge these concepts, whatever the opinion of the exhibition’s creators might be.

The director of the museum explained that they want to show as many Polish identities as possible, both in an ethnic and religious sense: Greek Catholics, Orthodox, Unitarians, Protestants and Jews. He also suggests that it is interesting to examine the processes of how different ethnic groups – Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Jews – tried to create their own political identities, which sometimes, for example at the formation of the independent Polish state at the beginning of the 20th century, lead to dramatic decisions for many who had to chose. One sibling signed the Lithuanian declaration of independence, and the other one became famous for being the first president of the Republic of Poland. Or in another family, one sibling became chief general of the Polish army, and the other became an emblematic figure of the Ukrainian nationalist movement. The same is true in the case of Jewish people: there was a small group identifying themselves as Poles within the Jewish religion, but the majority chose between being Jewish or Polish, and if they chose the latter one, they became Catholics in most cases, as well. Creators of the exhibition wished to introduce as much of these decisions and life paths as possible into the exhibition, displaying portraits of actual families.

Polish history has had numerous uprisings, which frequently led to an enormous number of casualties and financial sacrifices. There were always debates whether they were worth it in the end. Kostro believes that certain historical patterns repeat themselves, while others do not, because of the previous examples. The fact the Solidarity remained a peaceful movement can be partly attributed to the bloody outcomes of the Warsaw Uprising. The past influences us, but we are not its slaves. We always have an opportunity to draw conclusions and react differently.

This article was written as part of the East Art Mags residency programme, in partnership with artPortal.hu.

The programme is supported by the Visegrad Fund.

This article was written as part of the East Art Mags residency programme, in partnership with artPortal.hu.

The programme is supported by the Visegrad Fund.

Imprint

| Index | Anita Gócza East Art Mags Esztergom Castle Museum Katyń Museum Maria Kobielska Museum of the Second World War POLIN – Museum of the History of Polish Jews Robert Kostro Warsaw Uprising Museum |