Words are ‘things’ according to the poet, Dr. Maya Angelou[1]. They are things that penetrate our bodies, permeate our clothes, stick to the walls of our homes and our institutions. They are things that require care in their use and they are things that can be weaponized. Words targeting the LGBTQIA+ community have become a widely-deployed ammunition in Poland at both the state and local level. During the summer of 2020, at a critical moment in the Polish presidential campaign, the sitting President (and soon after re-elected) Andrzej Duda declared that queerness is an ideology, one that must be fought back against. The ruling party (PiS) declared the election to be a “choice between the red and white Poland and a rainbow Poland”[2]. More recently, the Polish Minister of Education, Przemysław Czarnek, declared that the queer community is unequal to ‘normal’ people, and that we shouldn’t listen to the ‘idiocy’[3].

But of course this context is unfortunately not unique nor new, this type of rhetoric has assaulted the world-wide queer community for generations. A new book by New York City-based Russian artist Yevgeniy Fiks, Dictionary of the Queer International, is, in many ways, an acknowledgement of these aggressions. Emerging from the artists’ long-term interest in the languages of the marginalized, this dictionary of ‘queer defense language’ confronts this relationship between language, culture, and power. It is also in this soil that the seeds of Biblioteka Azyl, a crowd-sourced queer library that is being established by Polish artist Filip Kijowski at Galeria Labyrint in Lublin, Poland, have been planted. While formally unrelated, both projects grow from similar seeds. I recently sat in conversation with both artists individually regarding these recent projects. And despite speaking from two vastly different points on the map, New York City and Lublin, Poland, both conversations orbited the same topics: marginalization, the experience of being queer, the gesture of invitation and the importance of community, and the flexibility and power of language and its role in and around our political, social, and individual bodies.

Following the forward to the Dictionary of the Queer International is an essay “From Evgeny to Yevgeniy About A Particular Type of Blue” by Evgeny Shtorn. It’s an unbelievably intimate, tender, and quietly violent narration of a queer boy growing up on the border of the “Central Asian steppe”. Shtorn recounts his memories of spending time with other local boys in casual, experimental, intimate and pleasurable sexual exchanges, the nature of which became transformed in a defining moment of discovery that these activities and feelings had a name, and that name according to the Brezhnev-era Soviet encyclopedia was ‘gomoseksualizm’ (homosexuality). The book defined it as an unnatural sexual perversion which could be punishable by USSR criminal law with up to eight years imprisonment if ‘muzhelozhestvo’ (sodomy) could be confirmed. Shtorn refers to that moment as the day that his shameful, yet innocent pleasures became a crime. That the tenderness he experienced was exchanged for depravity and danger[4]. While less explicitly defined, Kijowski’s description of growing up “a gay kid in Poland” had similar tones of exclusion and discomfort; not having access to queer people, to queer culture, to community, for a way to understand himself and his place within a larger, more wholistic narrative that included the queer community as a viable, acceptable, constitutional way to exist. This lack is in large part the inspiration for Biblioteka Azyl, and also a primary reason why Kijowski chose to live outside of Poland for the past 15 years. His journey back is a familiar story in 2021, the result of the pandemic making decisions for us that we might not have on our own. But this extended time forced Kijowski to see what has been happening to the queer community in Poland firsthand, and it is this that has shifted his course and helped him decide to stay more longer-term, rediscovering this time not only as an opportunity to create resources, to be a voice of advocacy and agent of change, but to be a leader in this charge.

The divisive presidential campaign speech last summer compelled Kijowski to know how this rhetoric was affecting individual people. In the past year he has spoken with over 1,000 members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Hate speech and violence have increased markedly over the course of the past two years in Poland, citing countless examples, including the ‘LGBT-free zones’[5] that have been established in dozens of Polish municipalities and physical attacks on individuals participating in Pride marches across the country, with little to no condemnation from authorities. From his conversations, Kijowski realized that people need a space to just be together, to be welcome in, to just exist as they are. He suggested that having a physical space is akin to an invitation. And so this past April, on the invitation of Director Waldemar Tatarczuk, Kijowski began a year-long residency at Galeria Labirynt, a space notorious for its tenacious support of the LGBTQIA+ community. His first action was to initiate Biblioteka Azyl.

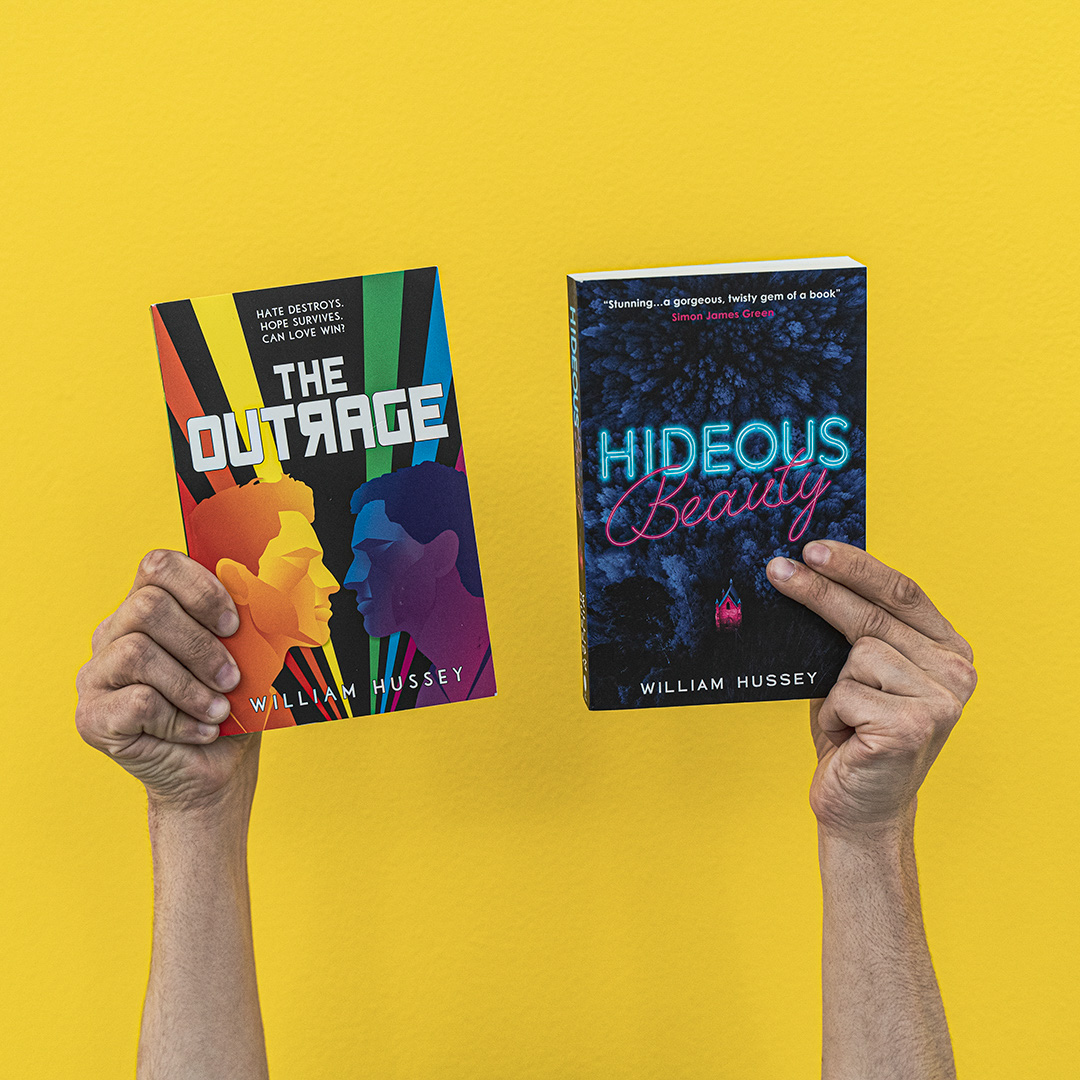

The call for contributions was launched in April, and since then Kijowski has received a flood of support. In our conversation we spent a lot of time focusing on the notion of asking and the mutually beneficial nature of exchange, and the care and courageousness embedded in this project, both in the radical gesture of creating such a space and within those that choose to enter this space. He also spoke at length about the empathy and flexibility needed to transition these seeds of acceptance and normalization of the queer community into everyday modalities. Kijowski underscores the joy that is experienced from not only receiving, but from giving back, which is a critical part of this gesture of creating the library— he sees it as a space for the generations that are growing up now or 5 or 10 years from now who need support, who will need a place to feel that they can find themselves, that they can see themselves within, can shape a future from. Kijowski also emphasizes that this is a place for parents, for family members, for friends of the queer community, for anyone who might be struggling to understand. It is a space for visibility and for community. The library is being amassed one book at a time through international contributions, there are a few titles which Kijowski has sought specifically and in these cases his queries have been overwhelmingly met with support and enthusiasm by authors or publishers or shop owners. There are essentially no parameters for the library, all materials currently being sent are being accepted. When asked if there were specific books he’d hoped to receive, in addition to biographies, non-fiction, and other conventional genres, Kijowski suggested that he aspired to create a diverse collection of novels for the library: stories that talk about friendship, love, relationships, family, etc. where the queer characters are the protagonists, not tertiary or peripheral characters who reinforce marginalization and stereotyping, so that we as readers have access to how they think, how they see and live in the world as central, critical figures in a narrative.

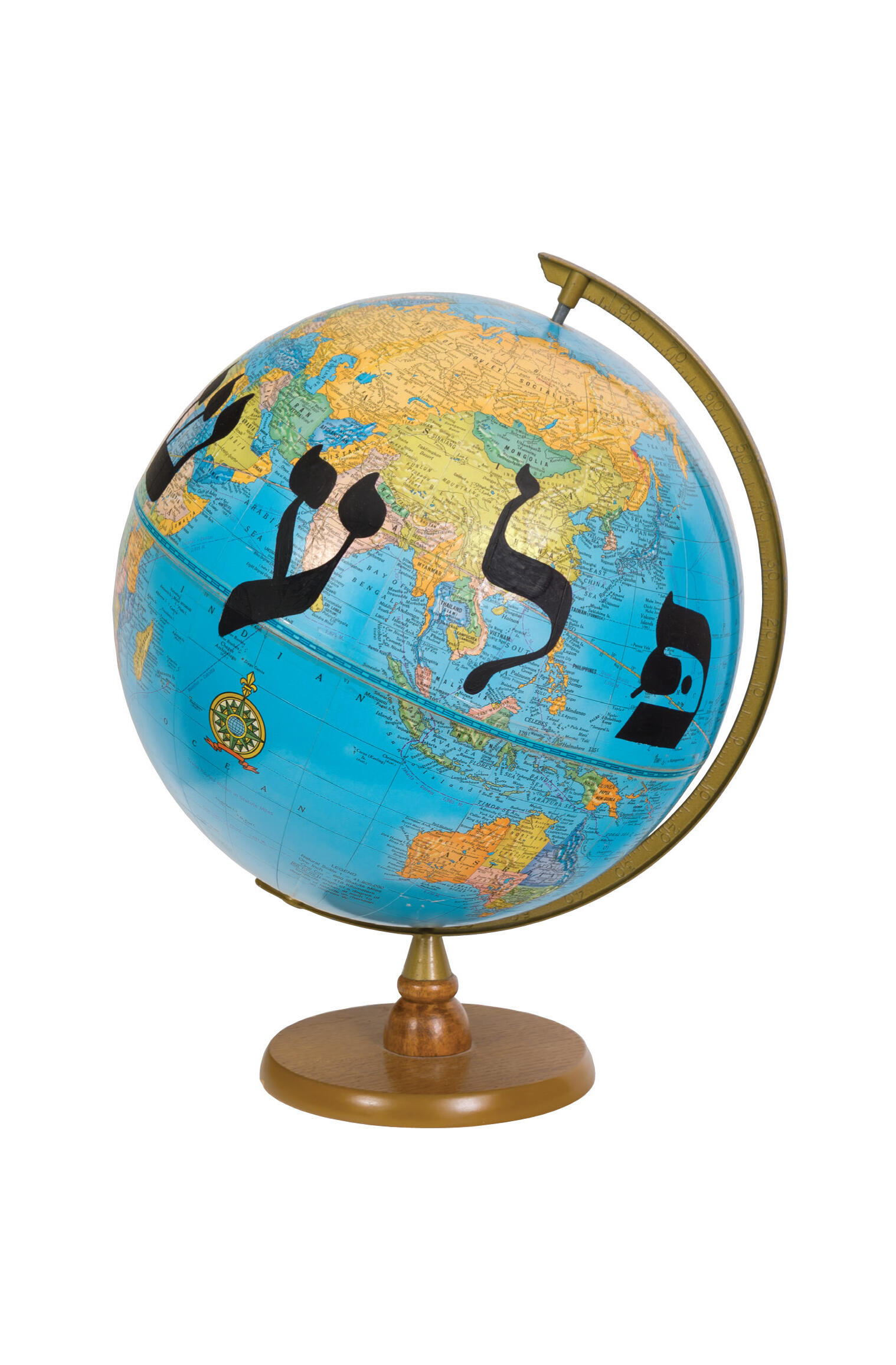

A similar invitational gesture was also the starting point for Dictionary of the Queer International. When the project began in 2018, an open call was issued by ArtsEverywhere[6], a Canadian-based platform for contemporary art. Fiks had dreams of it being globally received, but the reality is that the contributions ended up being primarily from within his circle of the contemporary art world, regionally-specific to East and Central Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The book, which contains hundreds of entries, is divided into descriptive categories, such as ‘People, Identities, (Re)Slurs’ and ‘Body and Mind’. This is as far as the ordering goes as words are not listed alphabetically or according to region, but rather the essential order in which they were received, and are even listed in the local languages that they arrived in, which represent over 30 countries including the US and UK, Korea, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Tunisia, Latvia, Mexico, and China.

Curiosity about his chosen classifications gave us the opportunity to talk about the flexibility of language, and how nouns and proper names can become verbs, how ‘foreign’ words become adopted and adapted into local languages, and of course how the meaning of a word changes depending on the mouth that speaks it and the tone in which it is delivered. This point is a sobering one, that we are reminded of at different points through the book. Even within this vetted community some of the contributors had been asked by those in their local communities to not pass along certain words so as to keep them usable within their circles. Each entry is a window into a complex constellation of histories—personal and political, trauma, hope and desire, and from it, an unfixed and multi-dimensional language begins to emerge from the liminality.

Fiks grew up in Moscow and emigrated to New York in the mid 90’s. When we began discussing the introduction to the book by Shtorn, Fiks first focused on the difference in their names, and how what appeared to me as a quotidian personal choice, rather tells a story of migration and identity. Fiks tells me that the spelling of his name (Yevgeniy) is the official translation of the Cyrillic Евгений, which was used by the American Embassy in New York for Russian citizens during this specific time period of his relocation. If you emigrated legally with proper papers, this tale is retold each time your name is written. The words and names of marginalized peoples is something that Fiks has dealt with in his work for some time, Dictionary for the Queer International comes out of this crossed interest in language, in the communist histories of homosexuality, of queerness, both its’ negative and positive sides. And while Volume I of Dictionary is decidedly his work, he notes that it is only a beginning, and that Volume II will very likely have a different initiator. And because of this, whomever takes this on will be able to grow the project in a different direction, as he notes not only were there geographical lacks but also in terms of gender as most entries are presented from a gay, male perspective. Female, trans, non-binary voices, mixed socio-economic classes or professions are not well represented, so Volume II will ideally address this. Fiks playfully suggests that the book is intended to be a step in the direction of a ‘utopian fusion’, a non-hierarchal queer language where we can begin the process of shedding our cultural, social, economic, and geographic boundaries. A place where languages have the potential to merge without privileging American English, which he quickly follows up by saying through a laugh that he is not interested in reproducing a queer Esperanto[7].

Kijowski also noted a feeling of deep responsibility to the LGBTQIA+ community to not prioritize his own singular experience and perspective, but to consciously try to build this collection with as many voices and perspectives as possible. And so to consciously encourage diversity he offers the possibility for individuals to contact him directly about the books that they want and need in the library, which he will source and acquire. And in yet another ambitious initiative to inspire dialogue and understanding with those less compassionate to the cause, there are also plans for the library to travel to the various ‘LGBT-free zones’ throughout Poland, where local citizens will have the opportunity to engage directly with the people and materials of Biblioteka Azyl.

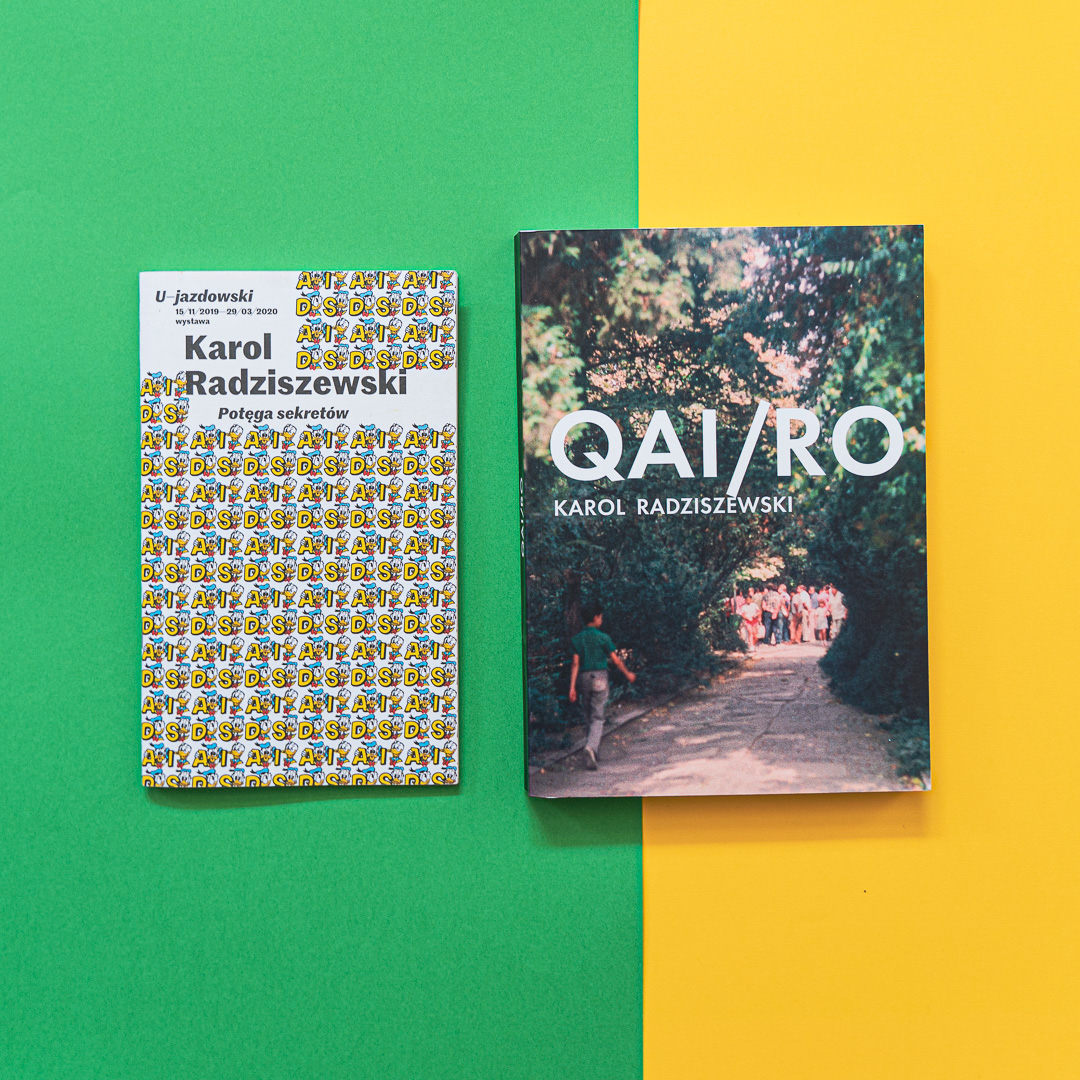

As Fiks references in the forward to Dictionary, a steady re-emergence of populist nationalism is threatening the health of queer communities worldwide, which is illustrated in a newly published index by the Brussels-based NGO ILGA-Europe which has ranked Poland 42 of 49 for its support of LGBT people in 2020. But what these countless examples of violence, oppression, and neglect for our queer families at state and local levels also inspires is greater resolve and solidarity from within. It is a path well-paved by predecessors and contemporaries alike, including organizations like Queer Archives Institute[8] initiated by Polish artist/activist Karol Radziszewski in 2015 and the US-based Queer.Archive.Work[9] founded by artist/educator Paul Soulellis in 2020. It is this lineage that Kijowski and Fiks exist within; the activist work being done to create not only safe but flourishing queer communities, expanding and reworking heavily gendered and binary languages to reflect a more dimensional mode of communication. The countless efforts to promote patience, care, and education throughout the communities that are most emboldened by hate and fear. The platforms provided by individuals and institutions ensuring that there is a place to make visible the countless queer, trans, non-binary, or otherwise marginalized artists working internationally, despite the potential for consequence. If we are ever able to measure the power of words, it will be within the halls of places like Biblioteka Azyl and in books like Dictionary of the Queer International where their weight will be fathomed.

Contributions to Biblioteka Azyl can be addressed to:

Galeria Labirynt

Filip Kijowski

ul. ks. Jerzego Popiełuszki 5

20-052 Lublin

POLAND

[1] Dr. Maya Angelou “The Power of Words” Oprah’s Master Class, OWN Network, 2014

[2] referring to the colors of the Polish and LGBTQIA+ flags

[3] D. Tilles, ‘Poland ranked as worst country in EU for LGBT people for second year running’, Notes from Poland, Kraków, Poland, Fundacja Notes From Poland, 2021

[4] Shtorn, E. (2020) From Evgeny to Yevgeniy about a Particular Type of Blue in Dictionary of the Queer International. Ontario, Canada: PS Guelph.

[5] https://balkaninsight.com/2021/04/15/neither-in-nor-out-the-paradox-of-polands-lgbt-free-zones/

[6] https://artseverywhere.ca/

[7] Esperanto is a language created in the late 19th c. by Polish physician Ludwik Zamenhof as an international medium of communication, based on the roots of several European languages.

[8] http://queerarchivesinstitute.org/

[9] https://queer.archive.work/