This interview with Bita Razavi was inspired by her fresh and bold stance on identity subjects. Her works, often related to her biography, speak directly and honestly, without exaggeration nor too much modesty. Bita Razavi is born in Tehran, but lives and works between Helsinki, Finland and Estonian countryside. In the interview she recounts her experience of being part of several cultural contexts, feelings of familiarity and unfamiliarity, as well as reconciliation. She sheds light on the inner workings of social systems in relation to the political structures of various countries.

Because of her experience of living in Iran, Estonia and Finland, she is well equipped to reflect on the relationships of these cultures and on the perception of her heritage in the Western world. For instance, Razavi’s work “Pictures from Our Future, Pictures from Our Past” (2018) started from a situation on the street in Tartu where a young man said Razavi was a “picture of the future of Estonia”. In the series of photographs, we see Razavi embodying the average Estonian woman in various everyday roles. There also feature photographs of empty country houses that have been abandoned, while dropping hints towards the radical social changes connected with the refugee crisis and urbanisation processes, but also the memory of the violent deportations in Estonia’s past.

Alongside her autofictional works, which this interview mainly concerns itself with, she also has shown herself to be a playful experimenter in form. In “The Dog Days Will Be Over Soon” (2019), she exhibited landscape shots from video games alongside PC hardware on which she had cultivated real live moss and other plants. This series points towards both the merging of artificial and natural materials, and the growing distance between humans and wild nature. While we are enjoying increasingly realistic video, VR or XR renditions of perfect landscapes, the rapidly diminishing ranks of flora are left to cope with the stress of finding habitable ground in a sea of non-biodegradable material.

Regardless of the subject matter and chosen technique, Razavi’s work often embodies the qualities of a tactical tool. The language games and materials is a ruse to bring us face to face with difficult ethical questions, be they social or ecological. Another example of this is “A Coloring Book For Concerned Adults” (2017 – ongoing), a riff on the plethora of colouring books of mandalas, plants, etc., marketed as a stress relieving pastime for people of all ages. In Razavi’s series of colouring sheets she instead addresses various global and local issues such as Iran-US relations, lack of social security or industrial pollution.

Bita Razavi, ‘Pictures from our future, pictures from our past’, 2016-2018, series of 14 photographs

This summer, Bita Razavi in collaboration with the artist Kristina Norman and curator Corina L. Apostol, were selected to represent Estonia in the upcoming 59th Venice Biennial in 2022. Their project entitled “Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance” deals with subjects like nationhood, belonging, and colonial exploitation through the representation of tropical plants. It also includes works by Emilie Rosalie Saal (1871-1954), a painter who was born in Tartu, educated in St. Petersburg, and is best known for her numerous paintings of tropical plants that she made in Indonesia (that time the Dutch East Indies) where she spent 22 years. She was a cross-cultural figure who exemplifies how people have always been interconnected with regions far-off, just as the authors of the “Orchidelirium” project Razavi, Norman and Apostol, who use Estonia as a meeting point for an agency that is above nationality and territories linked to them.

The exposition of the Estonian pavilion in Venice opens in April 2022and is hosted at the historic Dutch pavilion in the Biennale’s main exhibition grounds in Giardini.

This project started with a collection of some three hundred images of tropical flowers, fruits, and vegetables produced during the first decades of the 20th century by a forgotten artist from Estonia named Emily Rosaly Saal. Her works depict plants from different corners of the Dutch East Indies, then under the Dutch Empire, where she lived and travelled with her husband Andres Saal between 1899 and 1920.

Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi create new works based on Saal’s legacy, bringing in an unexpected perspective, various elements and a unique story that challenges the questions of colonialism, gender representations and botanical perspective towards both femininity and belonging. The project reflects eloquently the difficulties of entangled histories and the relationships between “perpetrators” and “victims”.

***

Bita Razavi, ‘Museum of Baltic Remont’, exhibition view at Kogo gallery, 2019

Marika Agu: You grew up in Tehran but evolved as a professional artist in Finland. In recent years your contacts with Estonia have intensified, through being involved in several exhibitions. What kind of challenges have these transfers from one cultural context to another revealed?

Bita Razavi: From an art maker’s standpoint, it has been mostly positive. When you move to a new place you see everything with fresh eyes and notice things that locals might not necessarily see. But I have realized that the reading of a work could change depending on the place it’s being exhibited. If you show a work related to one geographical location in another place, it finds a different reading, to predict that and control it, can be a challenge. And then of course it’s hard not to become subject to criticism when you make art about others whom yourself might not consider others.

Having more contacts with the Estonian contemporary art scene has been a very natural process for me though, as I have been spending so much time in Estonia anyway. I think the reason I finally started to be exhibited in Estonia is that I started making works in Estonia and in relation to the Estonian society which was again natural as I always reflect on my surroundings.

MA: For your graduation project at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts in 2011 you carried out a so-called legal performance, in which you married the artist Jaakko Karhunen. Even if it was formalised as an art project, it must have been very demanding emotionally. What triggered you to make this work?

It was a very risky work, as it’s illegal to get married for residential purposes and that would provide a reason for kicking me out from Europe. At the time of making this decision I was very hurt and frustrated, I wouldn’t do it now. Back then I was a student and had to extend my residence permit annually to be able to continue studying. While it is supposed to be a straight-forward procedure, instead it was something they bothered me a lot with. I remember my friends suggesting that I should marry a Finn to make things easier. I found it very insulting, I mean– why should I?

This coincided with the populist right wing party growing, and introducing their new policies related to immigrants, altogether with lowering the funding for contemporary art and allocating it to art that promotes national identity. At that moment I realized that I was a target of two of their policies – more strict immigration measures, and less funding for contemporary arts.

Back then it was a topic everyone around me discussed. So, I decided to bring the conversation to the public by making my thesis work about my transition from the institution where I studied at, to the institution of marriage as a ground for applying for a residence permit.

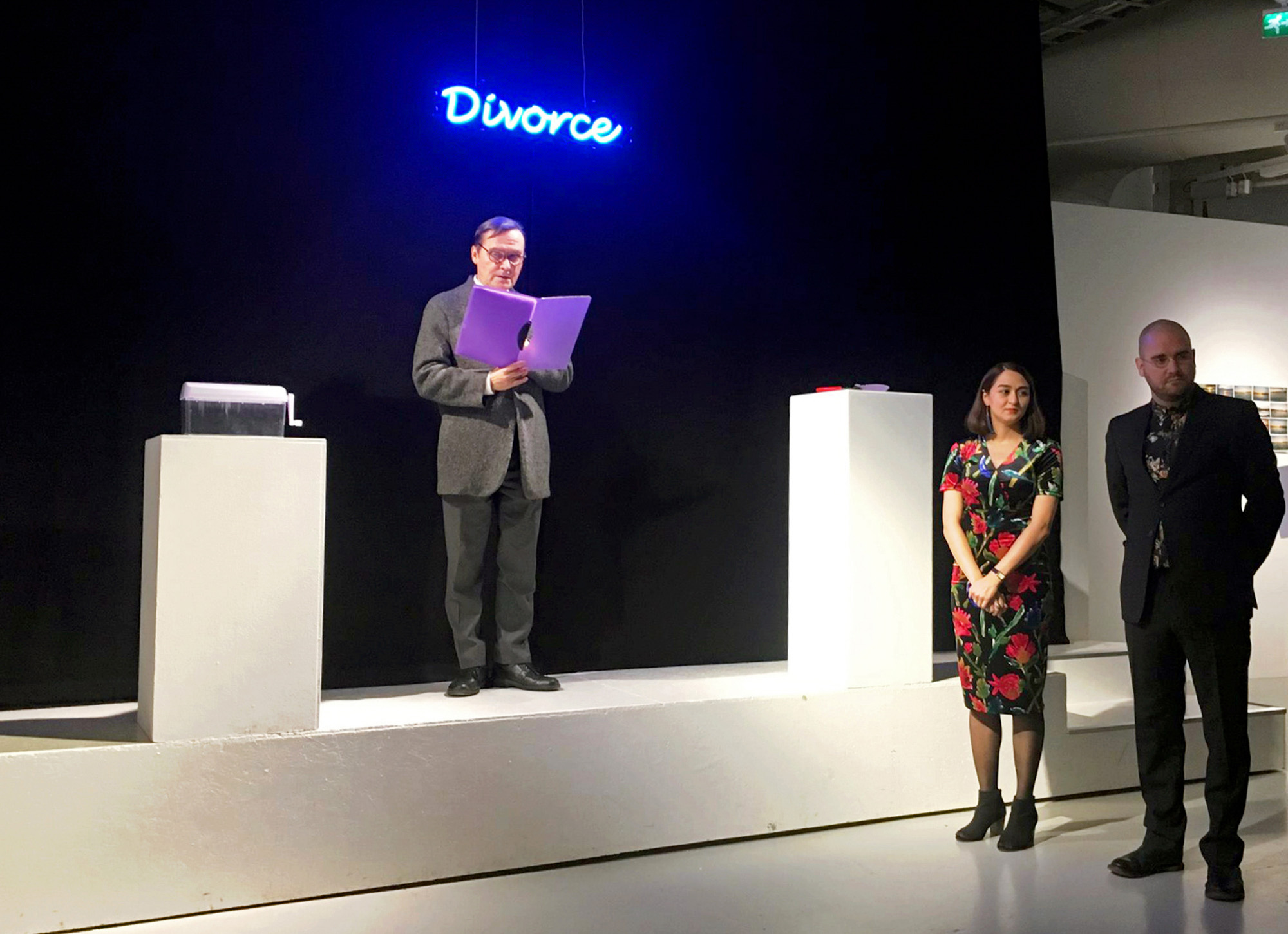

I ended the project in 2017 when I got my permanent EU-permit and applied for a divorce. I wanted to do the divorce ceremony also at the academy, so I contacted the administration, who were very interested to put it in the program of the 100th anniversary of Finland’s independence. That suddenly increased the number of printed invitation cards from 200 to 1000. The divorce turned into a true public event.

Bita Razavi, ‘Museum of Baltic Remont’, exhibition view at Kogo gallery, 2019

Siim Preiman: You must have struggled a lot during the time of your marriage, when you had to prove to the officials that the marriage was real. As this work is being bought by Kiasma – the central art museum in Finland, what does this gesture signify, does it legitimize your work, does it provide you with some immunity?

Actually, I didn’t need to prove anything to officials at all. After the performance I took the papers to the immigration office, I went there equipped with a microphone and a hidden camera to document the process of them harassing me, but it all failed. I applied for a long-term permit based on the marriage and I got it in a week.

About Kiasma legitimizing the work, it is something that I myself am wondering as well, if this will finally open up more conversation publically. So far this conversation has been avoided. Helsingin Sanomat (a local daily newspaper) managed to avoid writing about “How to do things with words” uncountable times, even though it was relevant to that historical moment and the rise of a populist movement. There was an intention not to address it. The newspaper wrote about the academy’s graduation exhibition while mentioning every work and concluding that it lacked a political stance, while ignoring my work completely. Later it happened with a duo-show, and the newspaper again ignored my work and wrote about the other artist. It kept going on, until I realized they might be trying to protect me. People are not sure if they are putting me in danger when writing about my work.

MA: Based on your own experience you have reflected on the very bitter and complex issue of being the Other, as well as xenophobia. Although you maintain a rather gentle and playful tone when addressing them. How have you come to such rhetoric?

Travelling between countries, and moving to the countryside, has made me forget about nationality. I don’t find myself so connected with the Iranians whom I see in Finland or Estonia, I don’t have any Iranian friends at all. I have lost that sense, but I totally understand if you don’t have this experience, and you have lived your whole life in one country or in a region like Europe and cannot imagine how it is to live in other parts of the world that you only perceive through the media. I totally understand where this fear of “other” is coming from, although I don’t approve of it, or think it is fair. The lack of communication between people with opposing ideas has resulted in a high level of tension, in most countries at the moment, and the rise of populist movements altogether. I’m always thinking what would be the middle ground in which you can alter that situation and try to understand both sides and reduce this tension.

MA: Since 2016 you have been devoted to renovating a yellow house in the countryside, and lately you were renewing an apartment in Karlova, and presented the combined findings in an exhibition “Museum of Baltic Remont” (Kogo gallery, Tartu, 2019). What kind of qualities do you consider important in a home?

What I care about when moving to a new place, is to turn it into a comfortable place visually. I’m sure that some other people are more concerned in the more practical aspects of a home. Although when I started working with my countryside house, there were much more basic matters like water and heating to think about. The house had been abandoned and it was extremely run down. I had never dealt with such problems, or even thought about them. In Finland there is a minimum living standard that is provided in every dwelling, in Estonia it’s not necessarily like that. Now I have made the house liveable and it is the biggest joy for me.

I don’t know anyone from my Iranian family or friends who could build a house or know how to fix something in their household. I find it amazing that in Estonia people know how to build things and repair them. Everyone is used to little adjustments. The first time I visited my partner’s house in Estonia, I learnt that he had renovated the whole house in a way that you could say he built it. That was really something magical, far from my mind. Later I learnt that it’s something that many Estonian people do.

Bita Razavi, ‘How to Do Things With Words’, installation view, 2011

SP: In Estonia, people often mix up the nation with the state. If you are disappointed in one, then you immediately have a problem with the other. Iranians are not happy with the current regime, although originally it was a popular revolution, but over time it has lost support completely. How do you preserve pride in your nation, but not include the state? Is it a schizophrenic position?

In the beginning, the revolution was equally leftist, intellectual and also religious. But it was immediately hijacked by the religious side and became something else. When the American embassy was attacked by a small fanatical religious group without permission from the government or negotiation, the temporary parliament opposed this act and resigned, and that was turning point towards the shift of power and the establishment of this totalitarian Islamic regime. That resulted in huge disappointment with the revolution very soon after it happened. Half of the population has lived with that disappointment their whole life. I am of a nation who is screwed by the regime on the one hand, and then the US and consequently other countries are screwing you from the other side, as if you are representative of the regime. It’s the worst possible position to be in, as you are attacked from both sides.

The moment Trump was elected, I thought now finally my American friends realise how it feels to be led by a politician who is not representing your views.

MA: Your work is a bit anthropological, considering how your artworks address everyday objects as carriers of identity. How do people become accustomed to collect similar objects?

I don’t have an anthropological method in principle, but it appears in the works that involve objects. For example, one of my works departures from my curiosity – why people feel obligated to own the same objects. It’s a symptom of homogenic small societies, where the definition of ethnicity and nationality is the same. For example, in Estonia these two terms are mixed, ethnicity is equal to nationality, although it is different where I was born, there are hundreds of different languages and ethnicities which make up the nation of Iran.

Bita Razavi, ‘Divorce Ceremony’, performance documentation, 2017

SP: In the end of 2019 you took a break from exhibiting. What encouraged that decision?

My idea was to take a break from non-stop producing and exhibiting, to stay in my countryside house in Estonia, and reflect on my life and practice but also the institution dominant system I was working within. The whole idea of renovating the Yellow House, which was abandoned till 2016, was to create a place for rehearsing hospitality, rest and non-activity, which is the most necessary and relevant activity in the current state of the world.

MA, SP: After such a retreat, I imagine it’s overwhelming to start preparing the Estonian pavilion at Venice Biennial. How do you and your work fit into the network of experiences and relationships that form the project?

You are right, it’s quite challenging to get back to my usual work rhythm, especially on such a project that requires long term concentration and dedication. But I think having a rather long break from work and exhibiting was very important for having the right state of mind to work on the proposal for Venice. When I was invited to join Kristina Norman and Corina Apostol in preparing the proposal for the Estonian Pavilion, I’d already had a five months break and the opportunity to reflect on my work. The thought that was bugging me the most was whether what is valued by the system, and the institutionalized art scene, has been influencing my practice. What I had been exhibiting during the recent years was very different from the dream image I had in mind when I made my first works in the early 2000s. Those works were deeply engaged with the space and I was more concerned about form and aesthetics. I had to go back and look at my earlier works to understand how my practice has evolved and if I was content and fully in charge of this change. This looking back forms a big part of my contribution to the Venice project. For Orchidelirium I’m creating a Garden of Abundance which will be intertwined with the space, visually much closer to my earlier works and conceptually more aligned with my recent practice and deeply in dialogue with Kristina’s work.