The return of the repressed

Eastern Europe is a collective identity chained to the past, based solely on the fact that during the Cold War Europe was divided into two – East and West. And even though the war ended and the Iron Curtain fell, the distinction and mental separation between the two Europes was kept alive. Initially, the reason for this was thought to be the “Western gaze” that looked upon Eastern Europe with uneasiness and distrust. The early discourse of East Europe was largely based on speculating with “the Western gaze”, emphasizing differences and working with repressed memory.

And then suddenly, the East seemed to gain a consciousness. Alongside repressed memory, nostalgia appeared. What had previously been despicable and cause for shame, now became something exotic. All of a sudden, East Europe became popular/hyped and held the world’s attention. Years of Russian propaganda together with the attack on Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea were probably among the most relevant reasons the East rose to the forefront. Possibly, this was the return of the repressed but in a deformed shape. Although not as the acute horror that fell upon us last year. But rather as a commercial sideshow with roots that seemed to exclusively connect to the dark recent past of the Soviet empire. The whole Eastern Europe – in its broad diversity – now labelled as “New East”, found itself lumped together in a gigantic territory between the Adriatic and the Baltic Sea and the Pacific Ocean. States and regions that had been freed from the occupation, become democratic and independent, once again found themselves in the same geopolitical sphere they had belonged to for 50 years. This circus called the New East made the Baltic states dance together with Russia, the Balkans, Central Asia and Central Europe. And once again, the remnants of Russian and Soviet culture such as concrete housing blocks, babushkas and gopniks were highlighted. Here and there, the Ribbons of Saint George and Russian tanks made an appearance[1]. Typical of the times and amplified by the social media, what had been “the Western gaze”, now became “a global gaze”.

This happened in the last decade, an era of politicization and polarisation. The soft power of Russia flourished and gradually transformed into war and violence. Although for some reason, the 2014 events never brought about an upheaval like we saw last year. Everyone knows what this upheaval means politically. What it does to us and how it impacts culture? That we will only know sometime in the future. Goodbye, East! Goodbye, Narcissus! is an attempt to analyse the massive change currently in progress.

The disappearance of the angel of history

Right at the beginning of the war, I remembered Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, which in Walter Benjamin’s tragic vision of 1940 became the angel of history. Soon after I discovered what Carl Gustav Jung had said at the end of the Second World War: “Now that the angel of history has abandoned the Germans, the demons will seek a new victim. Finding one won’t be difficult. Every man who loses his shadow, every nation that falls into self-righteousness is their prey.” Last year, it became clear, where these demons had nested. Of course, it is a place where self-righteousness is loved and shadows go unacknowledged. As we all know, creatures without shadows are vampires, feeding on the life force of others.

With the departure of the angel of history, trust towards history, Eastern European history has disappeared as well. And since the existence of East Europe is exclusively tied to recent history, it could even be said that trust towards East Europe has disappeared as well. Perhaps the rise of East Europe, in which I as an artist have also played a tiny part, has been nothing but the gentrification of a cynical geopolitical project? This is not a serious hypothesis but rather the kind of self-blaming that comes with contamination and pollution. It is not unlike a situation, where you discover that you have been abused and taken advantage of for a long time. And things that you felt were familiar and had considered as your own creation, now seem like an outcome of a strange manipulation. It was precisely the feeling of contamination that became the immediate incentive and motivation to create this exhibition. I think this feeling will linger for a long time.

There is no justification for dividing Europe into East and West anymore. It is clear now that East Europe as an identity marker is misleading, as it lumps together a pointlessly large part of our planet and homogenises the diversity found within that designation based on a short, merely 50-year-long historic episode. Over 30 years have passed since the fall of the Berlin Wall. In less than 20 years, another 50-year-long period will have passed. Will the socialist past keep defining us and many others forever?

East Europe as a narcissistic constellation

East Europe can be viewed as a psychic experience. Also, as a large constellation and a system of interactions, in the centre of which stands the narcissistic abuser. It cannot be merely reduced to relationships between states and regions. This constellation is abstract and universal but, above all, it forms a collective psyche, which is realised through individuals. The carrier of the collective psyche of East Europe could be the hypothetical creature homo postoveticus or post-Soviet human. We thought these had gone extinct but lo and behold! But who are they then? They are grandfathers and grandmothers with war-trauma, fathers and mothers who grew up during peace time as well as their children, who were born during the post-Soviet period or perhaps even in the 21st century. Together, they form the collective psyche of East Europe, where the traumatic past is latently kept alive and through that, the repetition of the trauma is made possible. And because of this pattern of conservation and transformation of the trauma, this psyche cannot heal.

I have been greatly inspired by the Australian psychoanalyst Neville Symington and his idea of narcissistic constellation, trauma conservation and transformation. I think that through these ideas, we can discuss East Europe as a collective psyche. I definitely do not have the ambition or the capacity to do this in a professional way and on the level of psychoanalysts but I think that similarly to the widely discussed collective trauma, we could try to discuss the idea of collective narcissism in a creative way. Primarily, because trauma and narcissism are closely tied together.

According to Symington one of the most prominent expressions of narcissism is refusal of life or the life-giver. I imagine, this is not unlike turning your back to sunlight. The narcissist constellation is a structure of the psyche, consisting of a pattern of the following elements: jelly, omnipotent external god, despicable worm and liquifiers.

The idea of the jelly refers to a person being traumatised and lacking a central organising core. The gelatinous mass of their psyche is shaped by external objects that contain god. This hard and strict god is usually embodied in figures who are put on a pedestal, such as figures of authority in society. The narcissist psyche sticks to such figures like glue. It also tends to stick to lesser creatures, who are seen as more fragile than they really are. The despicable worm is the person’s internal belief about its own core being. Essentially, this is the opposite of god. Both the god and the worm keep the person almost as their prisoner and deny the person the capability for free creativity. Liquifiers – envy, greed and jealousy – take care of keeping the jelly liquid. Symington calls these liquifiers the sustaining life forms of trauma. These are what keep the trauma alive.

The impulse to bring this approach to narcissism into the East European context was sparked in me by an article by Madina Tlostanova, where she describes how the Russian Orthodox tradition looks at the human – it is seen as a nuisance or worm[2]. According to Tlostanova, the reason for this is that in Russia, Christianity never went through reformation and so, a particular kind of anthropology was formed, in which people see themselves as worms, so we can only imagine how they see everyone else. Here, we could add the image of a stern god and pedestal figures, and the imaginary of one collective psyche easily takes a form.

According to Symington, the narcissist jelly-like psyche operates on the scale where a worm is on the one end and god is in the other. And to these extremes correspond two narcissist types, one of whom is arrogant and brags – the god. And the other, constantly putting themselves down and apologising – the worm. When I think about this, everything sounds so familiar. I feel I have seen it so many times – on television, in books. What comes to mind is the instability and contrasts so characteristic to East Europe. A constant sense of danger and anxiety, the ever-present need to numb or compensate for it. And somehow the thought about the “mysterious Russian soul” creeps into my thoughts as well. I cannot help my thoughts veering towards Russia, while East Europe feels like a funnel-shaped vessel with a hole in the bottom, opening just above Russia.

The unconscious and the return of archetypes

In the beginning of the 1990s, Boris Groys published the text Russia as the Unconscious of the West, which I believe is one of the most significant symbols of Russia’s collective narcissism. Groys’ text discusses how the “Russian Idea” that is part of the Russian cultural tradition excludes accepting psychoanalysis. In Groys’ text, all signs point to Russia as being similar to a person with a narcissist personality disorder, one who strongly resists therapy, refusing to accept that they are just like everyone else – that they have a consciousness and an unconscious. The narcissist Russia only seems to care about the fact that the unconscious is powerful like a god, which is why this is the only thing Russia can identify with. It cannot be anything less than a god! And so, it lives in its narcissist “exceptionality”, taking up so much space and making everyone around it suffer. Referring to Pyotr Chaadayev, who is considered to be Russia’s first philosopher, Groys writes that Russia cannot produce anything by itself, because creativity is possible only in the space-time of conscious experiences. In the consciousnessless Russia, where time and space are lost, achievements of all other peoples disintegrate, forfeiting their clear boundaries and ending up in arbitrary constellations. Sounds like he was talking about a vampire! And the same kind of arbitrary constellations and identities that are sucked dry and filled with poison are characteristic also to the “New East”.

I think that there is no better expression of the processes provoked by the war that began last year than the paintings by the Ukrainian artist Kateryna Lysovenko. Her work that quickly started to gain global recognition last year indicates that both in Ukraine and within the Ukrainian diaspora, a process, resembling renaissance has begun and is picking apart patterns that had formed during centuries of Russian imperialism. Lysovenko has worked with mythological creatures from the antiquity previously as well, but as they have now appeared in the midst of the war, we can really see ourselvs returning to archetypes. And also, that we are a part of history and similar to those who came before us. And that we go through similar processes, which we thought rather unlikely only fairly recently. Lysovenko’s work we see in this exhibition, evokes rituals we could associate with the ancient Olympic games, if not for certain elements that have been highlighted in connection to the war happening right now – the complete evisceration of humanity, while the human form remains intact. There is something innocent in Lysovenko’s human figures. They seem to lack consciousness and look as if positioned in a kind of a constellation. They express Russia’s consciousnessless. While the antiquity’s legacy to the world is Olympic games, the legacy of post-Soviet Russia is similar to a gym, where brutalities are carried out.

The work Morphology of War (2017) by Ukrainian artist and art historian Svitlana Biedarieva also refers to our return to archetypes. Aesthetically, it references Medieval illustrations that depict people transforming into war-hungry creatures. Characteristic to Medieval drawings, the creatures have an utterly neutral and blank stare. When a person reduces to this kind of war archetype, their personality is broken and they become possessed in a similar manner. The same kind of numbness, or perhaps even seeming innocence is present in Lysovenko’s work, where brutality and violence have been stripped of emotion, since emotion signifies humanity. This kind of unwilling transformation seemingly makes even the war into something that is not dependent on the will of people, making the war into a force of nature that people can do nothing about. Because a person is merely a shapeless mass without will, emotion and humanity.

The never-ending past

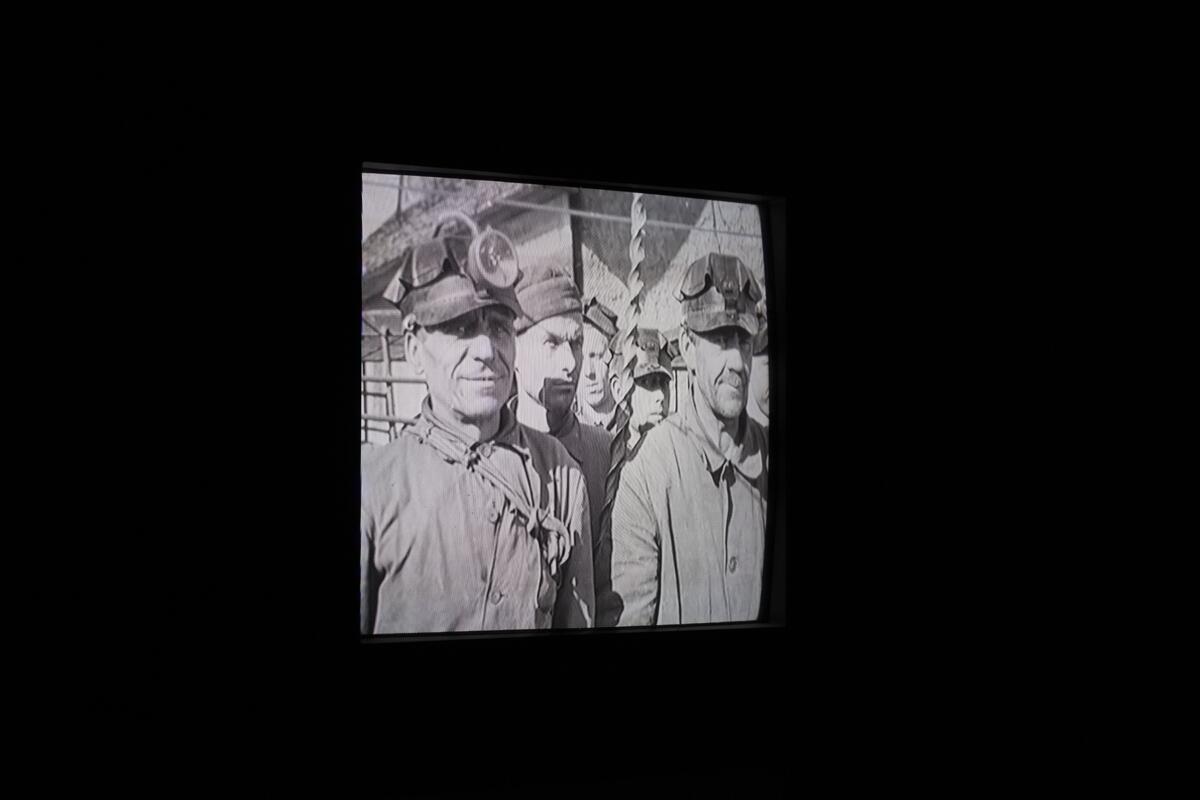

“What if the past never ends?”, asks Aliaxey Talstou, an artist of Belarusian origin, in his video of the same title, focusing on the monumental legacy of the Soviet Union that Lukashenka’s corrupt regime is taking advantage of. The video is made in Brest, during the period of tensions and protests in Belarus, which were met with violence and repressions by the authorities. The regimes of Lukashenka and Putin feed on the collective trauma that the society tends to compensate by nostalgically clinging to the past. And monuments offer the perfect thing to hold on to. I’d even say that this is what monuments are created for. But the past nine years have proven that monuments can simultaneously be dangerous weapons. In his poem, Talstou refers to an article by Hito Steyerl that discusses a tank that was taken down from the pedestal in the town of Konstyantynivka in order to use it to kill people in war[3] .Last year, the opposite happened on the Russian side of the river Narva – a fully functional tank drove onto a pedestal.

Monuments are objects that are put on the pedestal in a very literal sense. In essence, they are simultaneously fragile and strong. The Lithuanian artist Paulina Pukyte, who curated the Kaunas Biennial under the theme of (Im)possibility of a Monument in 2017, referred to Jacques Derrida in her curatorial text, more precisely to his idea that it is impossible to love a monument without recognising your own uncertainty and fragility[4]. And that is the thing – a monument is temporary and mortal. This can perhaps also explain the current need to remove Soviet monuments. On the one side, the removal proves their fragility, temporary and human nature. On the other, it also confirms their strength, power and the danger they pose.

In the fragility of a monument, we can see the worm, and in its strength – god. Similarly, the worm and god may hide in concepts like “people” or “East European”. This happens when “people” are understood as “the highest power” or a power that manages to endure all suffering. And at the same time, as a victimised, dispossessed, robbed blind and feeble mass that can be only set on the right path by strong authority. “East European” tends to be a version of “people”, rooted in victimisation, disdain and a mix of self-pity and pride.

Ghosts and shadows

It is a paradox that something that seems so strong can also be extremely fragile. For example, the Belarussian dictator Lukashenka has compared his country to a crystal vase – it is magnificent and fragile and that is why it needs to be in sure hands. No doubt that his corrupt system is fragile and shatters as soon as it should leave his grasp. Aliaxey Talstou conducted the ritual of breaking this system a couple of years before the massive protests began. It was 3 June, Belarussian Independence Day, when he stepped onto the Independence Square in Minsk, and having brought a bag full of crystal tableware, he started to break the items. Later, he took the crystal pieces in front of a Soviet monument in the Brest Fortress, symbolically named Courage. As if this were a hommage to Talstou’s action.

Paulina Pukyte calls this type of crystalware ghosts, remnants of a suppressed and unprocessed past. This is the kind of past the East European identity is based on. In this past, people who had been traumatised by war, deportations and other repressions lacked access to psychotherapy and society at large was too busy with covering up and suppressing shadows. It is also a past, where abusers and repressors could act with impunity. And they were publicly recognised for it. How could you acknowledge something if you have no consciousness? There is only the unconscious and repetition of trauma.

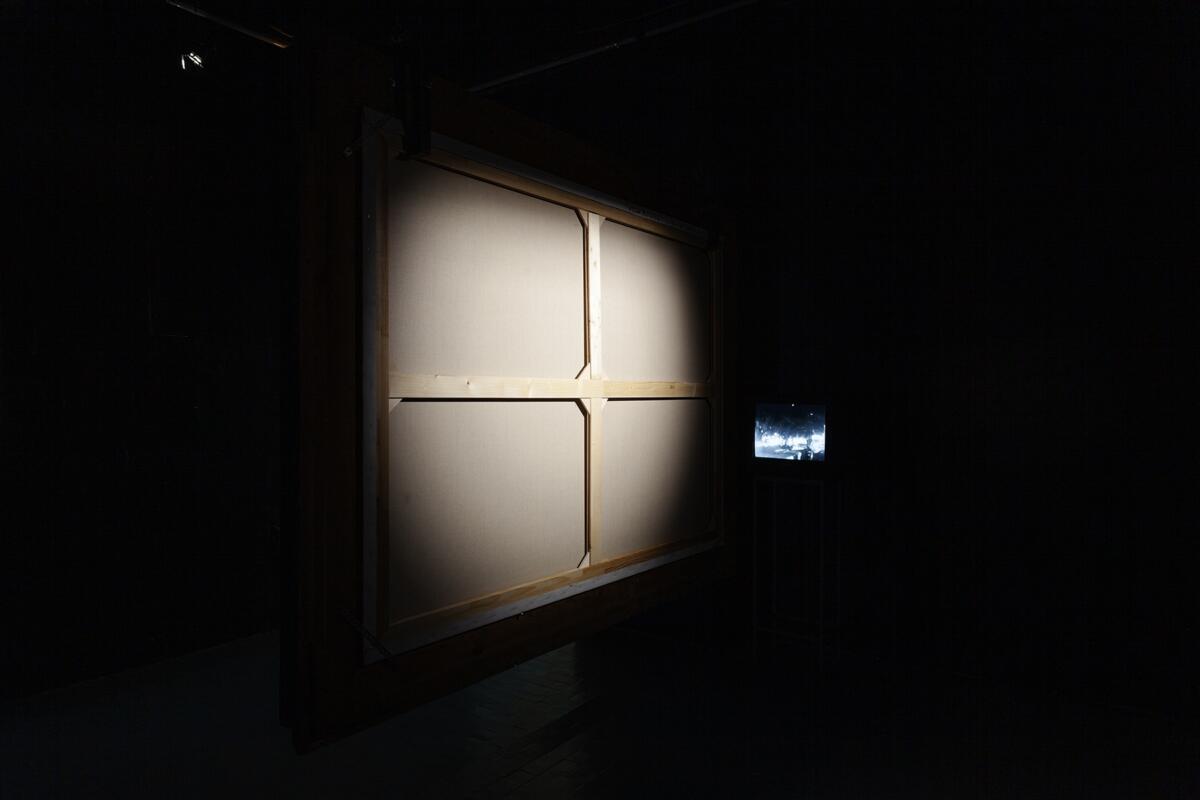

At the exhibition Goodbye, East! Goodbye, Narcissus! Pukyte presents her other work titled Shadows. It is an installation that makes shadows that often go unnoticed into material and spatial reality. Pukyte created shadows in places they should not be – in very visible spots, making it impossible to ignore them. In their materiality, her shadows resemble ashes, the aftermath of a fire or a catastrophe. Destruction caused by shadowless people possessed by demons.

Notice a mountain, look for a hole

Crystal vases are the perfect symbol for narcissist psyche and constellation. They are simultaneously fragile and strong. And hollow, constantly needing to be filled and demanding to be compensated for the lack. The question is, if a crystal vase is something that includes the element of cavity or is it, in fact, a crystallised cavity. I tend to think the latter, since one of the more prominent features of the East European psyche seems to be the hole – the lack, the cavity. Maybe this hole corresponds to the sustained life-forms of trauma – greed, envy and jealousy.

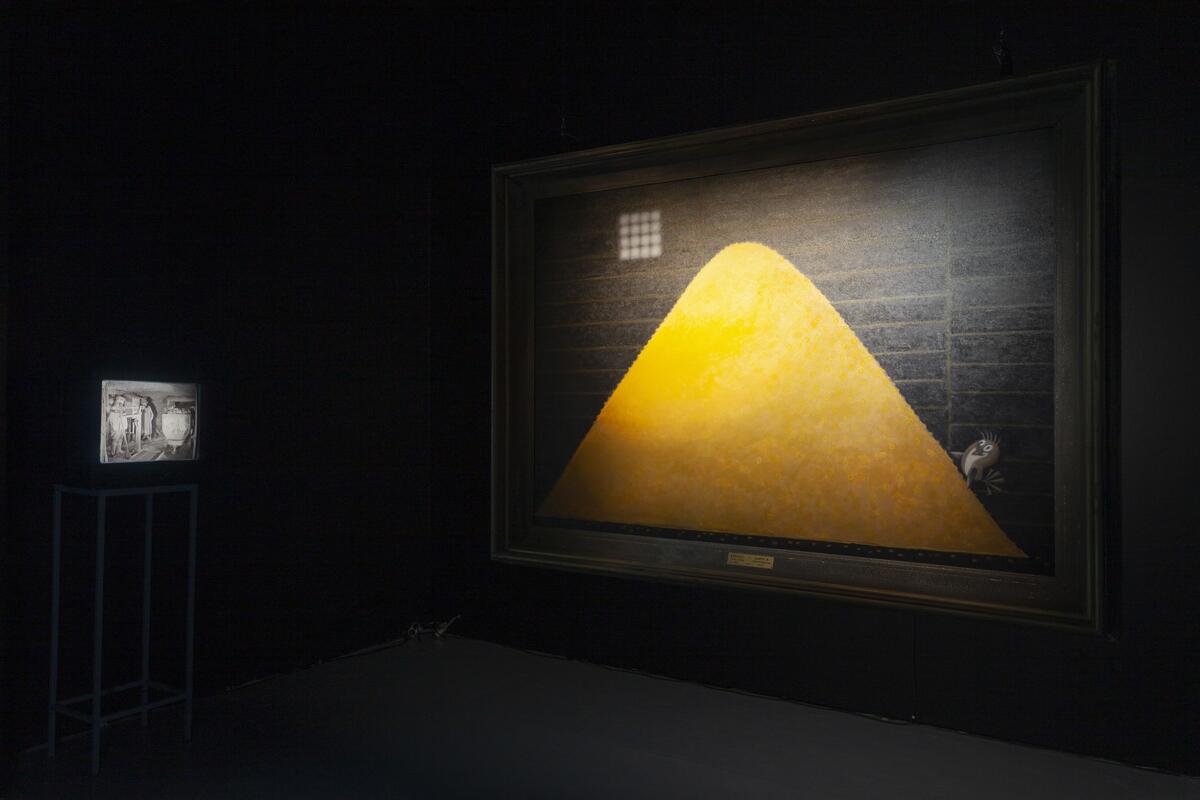

Abundance created by greed is always hollow. Coming back to Lukashenka’s regime, I am reminded of a story of a greedy sparrow (The Richest Sparrow in the World by Zdeněk Miler), who did not want to share his fortune with anyone and soon found himself sitting on a large heap of wheat all alone. This story was told by the Estonian artist Holger Loodus with his painting Crop for the State (2021), the title of which refers to the famous 1953 painting by Viktor Karrus, depicting the harvest following the forced collectivisation in Estonia. Loodus’ painting depicts a space resembling a prison cell and a large heap on top of which a little bird dances. The frame around Loodus’ painting was originally from Karrus’ piece. In some ways, this shows the relationship between the greedy sparrow and the Soviet legacy. The title Crop for the State expresses a lie that greed was hidden behind during the Stalin era just as it is now. And precisely for this reason, the past cannot come to an end. The past protects the prison cell like a wall – with a heap in the middle and a dictator on top of it. A picture like this almost forces us to think about the lack – the place these crops and abundance have been stolen from.

Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit is definitely among the foundational texts of Eastern Europe – a story about digging a foundation pit in early communism, accompanied by ideological slogans. Platonov was incredibly skilled in describing the surreal inhumanity of the situation. During forced collectivisations, people died like flies, and while the deep existential and ideological discussions were taking place, they killed each other almost without thought in the background. There are situations, where a person and an animal or a person and construction materials become one. By the end of the book, little progress has been made with the foundation pit. It is exactly the kind of archetypal pit that sprawls in the East European collective psyche, hollow like a crystal vase and in constant need on compensatory filling out. The heap Loodus depicts is, in essence, hollow as well. Similarly – under the field of wheat lies a muddy foundation pit.

Breakdown of the constellation

The intervention in Minsk Aliaxey Talstou undertook years ago expresses a will to shatter Lukashenka’s regime, which in my opinion is upheld by brutal force as well as a collective narcissist constellation, not only limited to Russia and Belarus but it also includes their close neighbours and those who admire and support the constellation from afar. But the crystal vases have been broken! And last year, the whole constellation began falling apart.

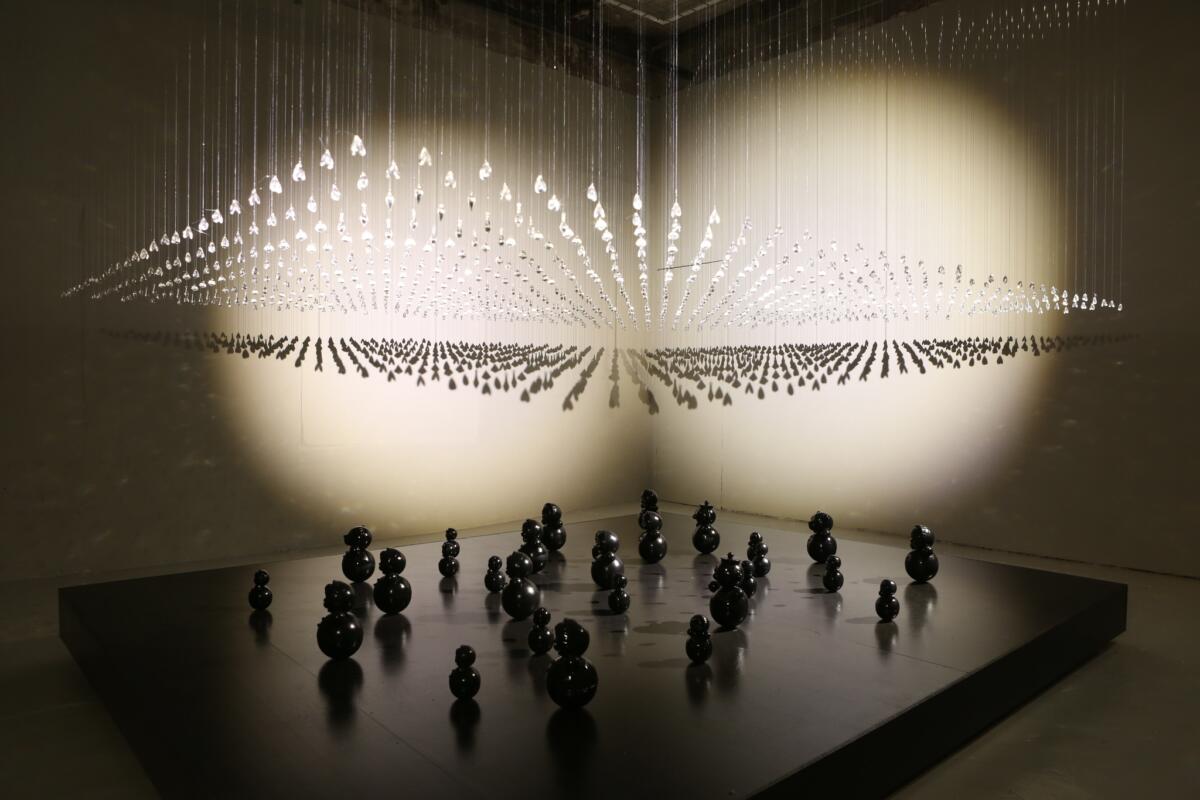

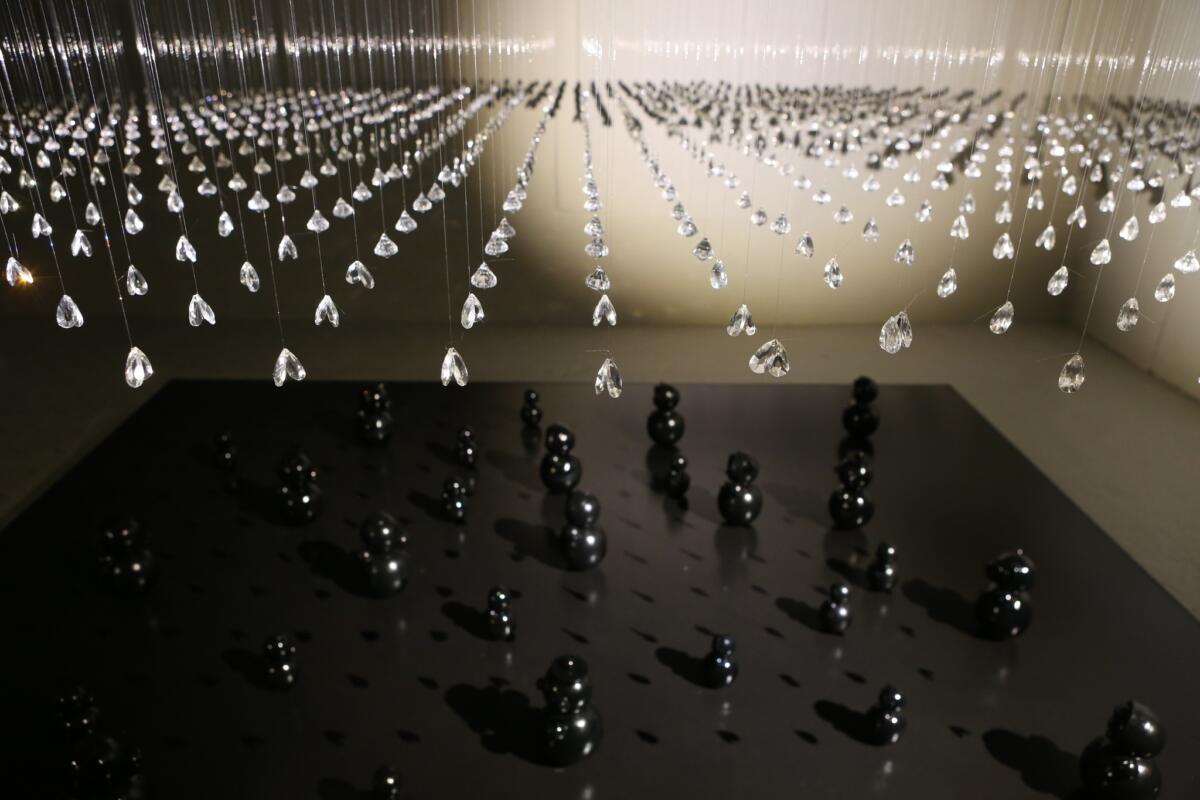

An installation consisting of pieces of crystal, created by the Estonian artist Elo Liiv, depicts the moment we are currently at. The crystal bowls have been shattered but the little pieces still remain up in the air and we do not know where and how these fall. We stand in the middle of explosions and are unable to see a tomorrow. But we can look at the pieces scattered in the air just as we would at the starry sky. Under crystals, the wobbly dolls are wavering. In Russia, wobbly dolls are called vanka-vstanka, which translates to Vanya, stand up! Indeed, Vanya! Time to stand up!

Narcissism is not something you can get rid of easily. It is not even really necessary to get rid of it. In the words of the Estonian psychoanalyst Endel Talvik: narcissism is like body temperature, we all have it. In some, however, the level is dangerously high. Symington discusses cases in which the temperature is too high, the kind of narcissism that verges on the edge of pathology, keeping traumas alive and interferes with mental health. So, I would like to end this text with Symington’s definition of mental health:

“A person is mentally healthy when they are capable of creating inner emotional capacity to seek truth, love, courage, integrity and tolerance.”

I would like to live in a reality that contributes to the awakening of this kind of mental health.

Tanel Rander

2023, Berlin

PS:

Holy void

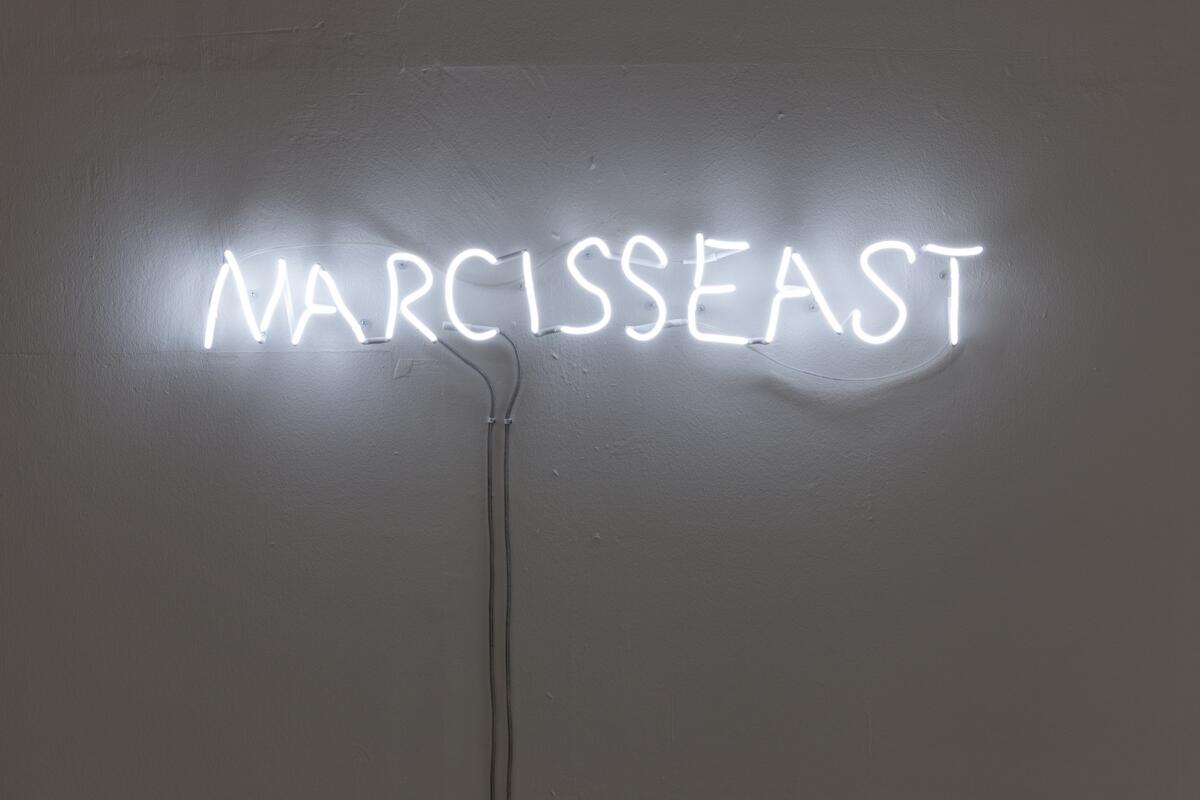

In 2017, the sign “OST” was removed from the roof of Volksbühne in Berlin. As if a reaction to this symbolic gesture, Kirill Tulin mounted a sign that reads “IDA” (“east” in Estonian) on the roof of EKKM. He did this as part of his solo exhibition Help for the Stoker of the Central Heating Boiler. Although the disappearance of OST and the appearance of IDA are stemming from very different motifs and backgrounds, these events can be read as the disappearance and appearance of East Europe in the symbolic arena.

Perhaps, EKKM is the only pedestal in the former East Europe, declaring their East-identity in such a direct manner. In a situation, where Soviet monuments are being removed en masse, while East Europe as a narcissist constellation is shattering, this gives us a great opportunity to think what might happen when IDA disappears from the pedestal.

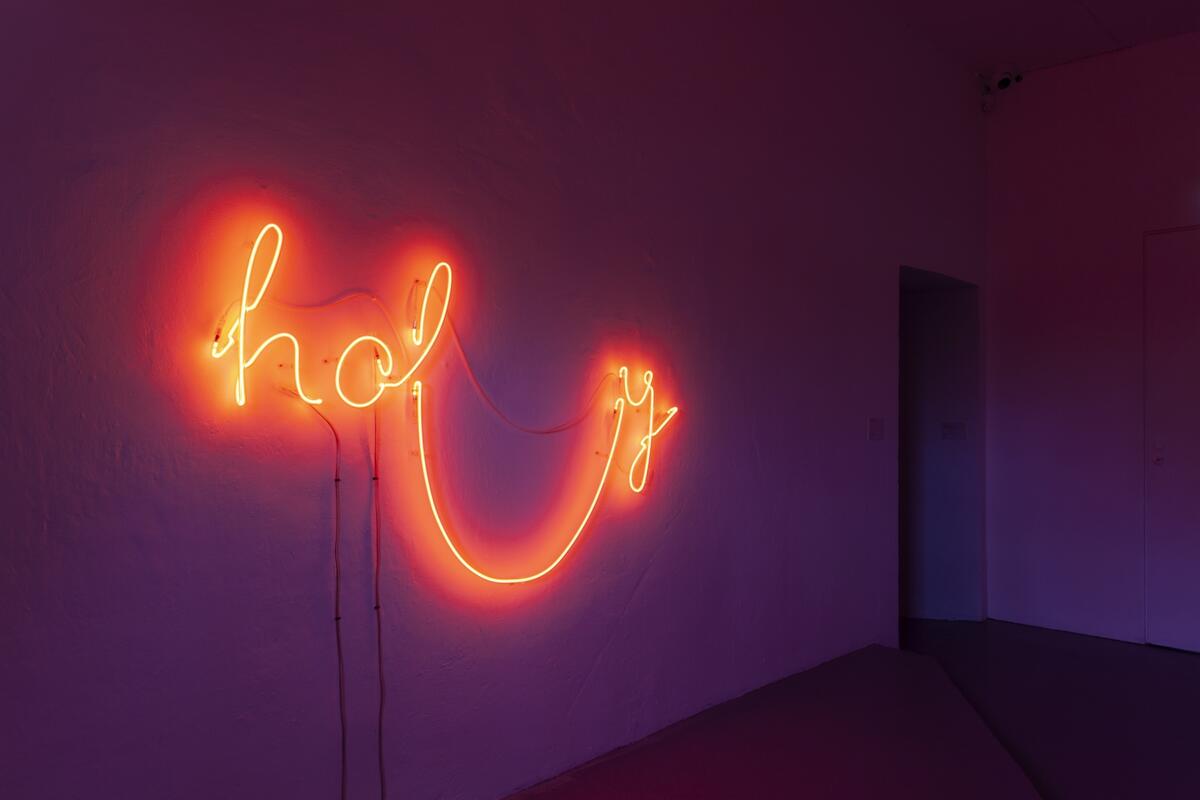

Currently, the IDA sign is delicately integrated into Sigrid Viir’s piece Holiday. If we remove the letters IDA, what remains is “hol___y”, pointing to two things:

- The fact that the current sign “Holiday” can essentially be broken apart into “Holy IDA” or “Holy EAST”.

- The fact that if IDA disappeared, a holy void would remain.

This is the kind of void I feel in my soul after saying goodbye to East Europe. What will happen to me if IDA disappears? This feeling is like a pit, an empty crystal vase, a lack. Narcissus seems to be broken but the holy void feels a little like coals smouldering in ashes. Or narcissus bulbs hidden in dirt. If IDA disappears, inevitably, something else needs to replace it.

I, too, took part of putting IDA on a pedestal – I wrote a text titled Help for the Incubator of the Eastern European, which by now seems to me like adding unnecessary fuel for the fire[5] . I began that text with a quote by Lukashenka and finished with describing a hungover morning of the poor homo postsoveticus. However, thinking of our recent correspondence with Tulin, it increasingly seems to me that the reason he put IDA on the pedestal might actually have been empathy, sympathy or even love towards the stoker of the central heating boiler, a role he personally took on for the duration of the exhibition. Maybe something like Karl Roßmann’s trust and sympathy towards the stoker on a ship[6] .

In a narcissistic constellation, sympathy does not have a place, except for when it is located outside the narcissist psyche – in the role of Echo, for example. Endel Talvik has said that Echo acts as Narcissus’ mirror and compared her to the interior of a vase – a lack[7]. Let us now remember the hollowness of crystal vases and the hole in East European psyche. That’s Echo. It is entirely symptomatic that as a character and an independent concept, she only appears in this text at this point. Even though she is one of the main characters of the Narcissus myth. In the myth, she fell in love with Narcissus, but he was in love with his own image and ignored Echo. Rejected, Echo was left repeating Narcissus’ words as an echo. And when Narcissus finally died, exhausted of admiring himself, his last words were: “Oh, marvellous boy, I loved you in vain. Goodbye!”. And Echo repeated after him: “Goodbye!”

[1]A few great examples: Nublu’s video Für Oksana and Tommy Cash’s video Give Me Your Money.

[2]Madina Tlostanova, Towards a Decolonization of Thinking and Knowledge: a Few Reflections from the World of Imperial Difference, 2009

[3]Hito Steyerl, A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War, 2016

[4]Jacques Derrida, Acts of Religion, 2002

[5]Available: http://barokkputo.blogspot.com/

[6]See Franz Kafka’s America

[7]Endel Talvik, Narcissus ja Echo. Müüt ja analüüs, 2013

Imprint

| Artist | Svitlana Biedarieva (Ukraine/Mexico), Elo Liiv (Estonia), Holger Loodus (Estonia), Kateryna Lysovenko (Ukraine/Austria), Paulina Pukytė (Lithuania/UK), Aliaxey Talstou (Belarus/Germany), Kirill Tulin (East/West) |

| Exhibition | Goodbye, East! Goodbye, Narcissus! |

| Place / venue | Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia |

| Dates | April 15th - June 4th 2023 |

| Curated by | Tanel Rander |

| Index | Aliaxey Talstou Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia Elo Liiv Holger Loodus Kateryna Lysovenko Kirill Tulin Paulina Pukytė Svitlana Biedarieva Tanel Rander |