Introduction

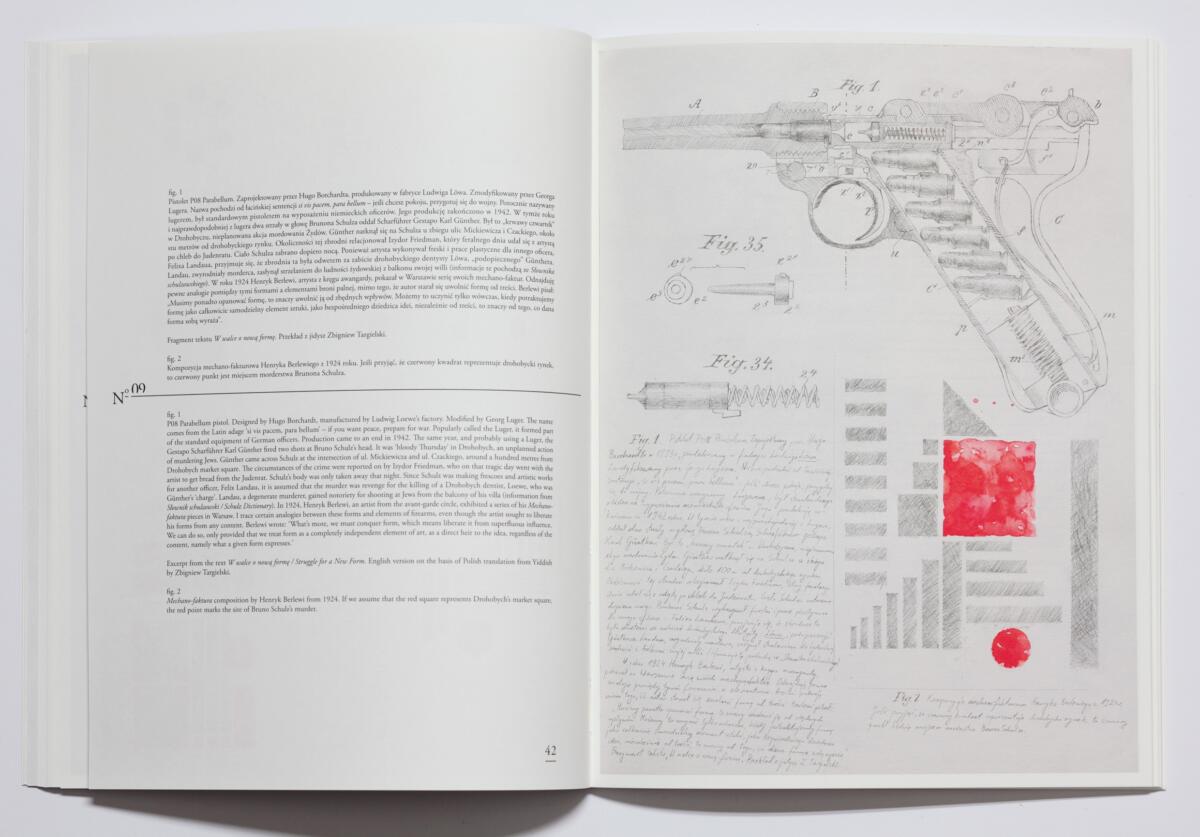

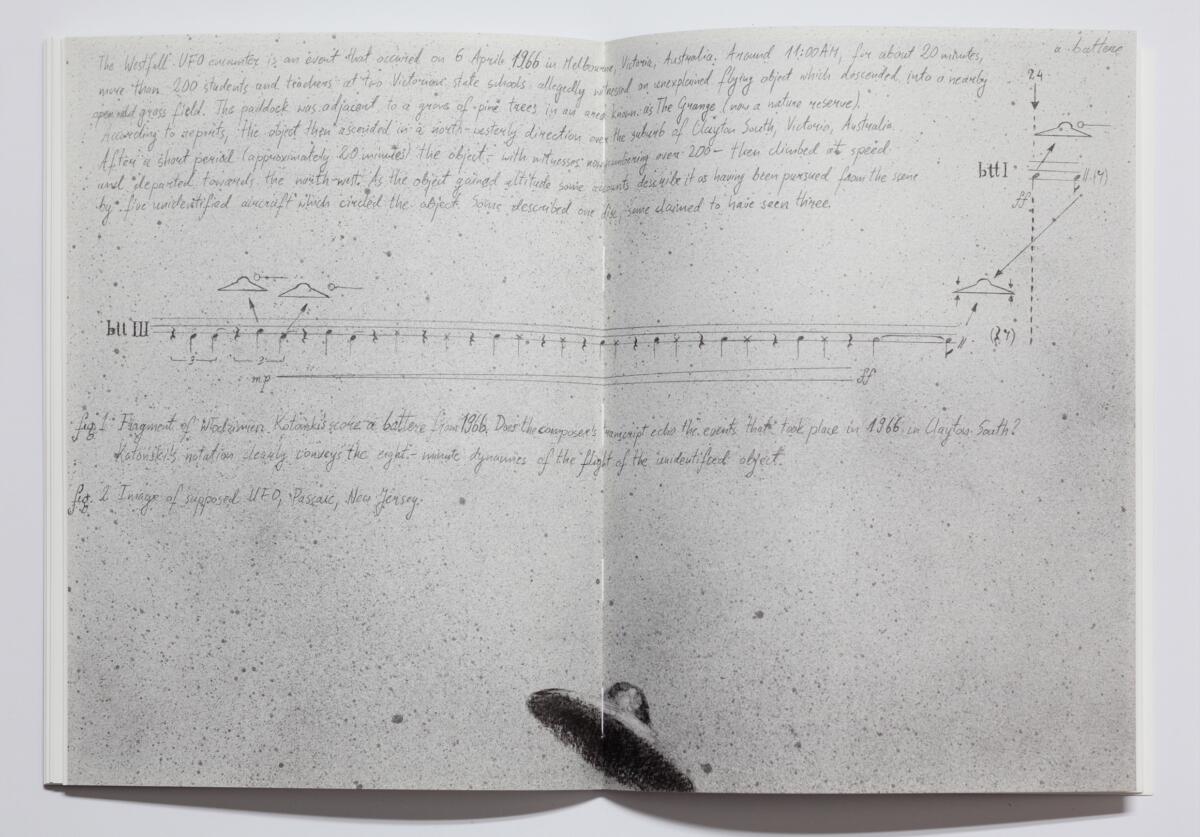

Paweł Książek’s Plates is a series of works which allude to the illustrative-cum-informational plates used in encyclopaedias, dictionaries and the natural history textbooks that became popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as incontrovertible compendiums of knowledge. They employ the same system for numbering the explanations, ‘Fig.’ plus a number and, in addition, they present juxtapositions of images with factual material and scholarly, monographic texts. They are intended to bring out surprising and revealing connections not only between individual events, works of art and the biographies of artists, filmmakers and musicians, but also in a wider aspect, between, scholarship, biology, philosophy and anthropology and, at the formal level, between the shapes, colours, and lines of sketches and scores. They are a vivid record of fleeting thoughts and notes based on quotations from scholarly studies. They reveal a particular model for interpreting selected cultural texts, a model which is grounded in the principles of assembling images, visualising selected quotes and noting individual, subjective analyses in one place. They constitute a specific collection and montage of fragments, autonomic, yet coherent, expressed in the form of connections between language and images, scholarship and art, intellect and intuition. Here, the interpretation of historical and scholarly material emerges on the basis of endeavours to develop a common language for presenting the facts through the determining rigour of historiography, as well as intuition and artistic imagination. In truth, it is an endeavour to create a compendium of alternative knowledge emerging in the sphere of visualised, intuitive connections supported by sources derived from available scholarly publications.

After all, Notes in the Margindid spring from the basis of the graphic and linguistic juxtapositions in the Platesseries and the interpretations formulated by the artist were treated as important research material.

Based on facts drawn from those works, all the episodic stories in Plates fall into cohesive narratives, while the numbering need not always be organised from first to last. There is neither chronology here nor a chain of cause and effect. At the formal level, grounded in montage, and at the semantic level, rooted in the exploration of episodic events, they point to an open-ended practice of creating a sequence of alternative interpretations in the sphere of cultural history, where every phenomenon and every concept has a relationship, often hidden. Because the plates do not constitute a closed formula, they can be developed in any direction with no real end. They bring to mind Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, a collection of visual phenomena fulfilling the function of illustrative-cum-informational plates and depicting artistic and social changes. Warburg’s practice involved juxtaposing all kinds of images from various epochs. They included photographic reproductions, illustrations and press cuttings and, outwardly, they had little in common which would provide a basis for altering a way of thinking about history and visualising collective memory within the concept of non-linear time. Like the Mnemosyne Atlas, which was created between 1925 and 1929, Książek’s plates turn out to be a kind of boundless visual archive, within the ambits of which, infinite interpretations based on extracting meanings from the most diverse images occur. Plates and the Mnemosyne Atlas finally convince us that every model of knowledge is a construct which can be undermined.

The problems broached by the Plates series are focused on a great many diverse matters, from which we need to single out the primary questions of the artist’s role as a historiographer, an art historian and a (post)scholar. Can a detective-like and factual stance in a scholar-artist analysing a work of art by asking questions and carrying out individual, exploratory searches for connections between paintings and scholarly texts, have an influence on the history of art and, at the same time, on new and refreshing perceptions of artistic phenomena rendered commonplace in that history? Can the schematisation of scholarly works be broken and a new concept for scholarship indicated? Can an art historian base their studies on interpretations formulated by artists? Can an art historian themself improvise? Can art, in the end, give rise to changes in the field of art history itself?

(…) all the episodic stories in Plates fall into cohesive narratives, while the numbering need not always be organised from first to last. There is neither chronology here nor a chain of cause and effect

This book is an experiment showing the extent to which the deliberations of an artist can inspire historians of art and visual culture. After all, Notes in the Margin did spring from the basis of the graphic and linguistic juxtapositions in the Plates series and the interpretations formulated by the artist were treated as important research material. The notes do not take the form of finished texts and they are grounded in the parallel strategy adopted in the plates, in other words, the strategy of juxtaposing certain phenomena and concepts which are often ill-suited to each other. In the notes, the plates function as proven scholarly research and encyclopaedic entries which constitute the basis for formulating and developing ever newer written narratives. The notes thus follow the practice of creating episodic narratives on the basis of montage. However, unlike the plates, it is restricted to a montage of facts and interpretations expressed in writing. Those narratives have been stripped of images, but the reader can find all the motifs they address in the various plates if they follow the juxtapositions which appear in the notes referring to them. And that is not the final task, for the plates and notes demand to be arranged constant rearrangement in new juxtapositions in order to extract further parallels from them.

In pursuit of the rigour characteristic of scholarly research, the notes stick to the facts. At the same time, they contain a certain measure of improvisation played out against the backdrop of the material collected in the plates and this renders them distinctive. In fact, the process of writing them proved to be akin to automatic writing and literary practice. At this point, it is worth emphasising that ever since the moment in the nineteen seventies when Hayden White put forward a new look at the content of texts in the field of historical studies, suggesting that they be perceived as a kind of literary text, and ever since, more recently, James Elkins recognised art history as a particularly creative type of writing, attention has been steadily turning towards various aspects of portraying the past in narrational ways. Narratives most often appear in humanist studies as cohesive stories with a plotline based on previously collected and organised facts. Writing about the past is always narrative in nature and the results of our reflections, irrespective of whether the text is scholarly or a story based on facts, are always presented with the help of various narrative forms. The fragmentary narratives which appear here in the plates and notes convince us that we really only ever acquire knowledge in scraps. Recording and visualising knowledge in its entirety, an endeavour which emanated from eighteenth-century encyclopaedias, is not something that has been bestowed on us, although the possibility might, perhaps, exist.

In the notes, the plates function as proven scholarly research and encyclopaedic entries which constitute the basis for formulating and developing ever newer written narratives.

The dialogue between the Plates series and Notes in the Margin, between the attempt to connect scholarship and art, is simultaneously an experiment reminiscent of the composition of Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, presenting a collection of loose, apparently unconnected notes, rounding off and rounding out successive chapters of literary narrative. As far as building this singular dialogue is concerned, the numbering of the plates therefore turns out to be immaterial. They can be juxtaposed, transposed and assembled anew in fresh meanings. In the end, like Warburg’s atlas, the series has no end and can be developed perpetually, while the visual narrative rooted in drawing out meanings between the images could lead to ever-newer, unfathomable regions. Finally, it is also possible to conclude that, on the basis of the plates and notes, the truth about history can be conveyed in a significant manner. That practice is a task for historians and writers using written narrative and for artists, as well. After all, historical truth lies not only on the side of rigorous factuality; it can also be contained within the form of literary-artistic experiment. And that, in truth, is only found in a place where art and scholarship meet, at the contact point of uncertainty, ‘pataphysics, assumptions and proven theses, artistic imagination, intuition and the infinite process of carrying out intellectual analysis.

Note 1. Henryk Berlewi – László Moholy-Nagy

El Lissitzky’s arrival in Berlin in 1921 was an extraordinarily important event for that part of the city’s avant-garde milieu which went by the name of Novembergruppe. Deeming themselves revolutionary artists, the members of the group demanded change and the linking of social problems and artistic practice. This was the time when the political and cultural spheres of the Weimar Republic were becoming more and more clearly infiltrated by artists arriving from communist Russia. Before long, Henryk Berlewi came to Berlin from Warsaw. He was closely attuned to the concepts of abstract art and to the question of art’s pro-social influence.

Lissitzky and Berlewi took part in an extremely important event, the International Congress of Progressive Artists, which was held in Düsseldorf in 1922. The aim was to establish an international artistic union with the intention of creating the foundations for a new, democratic culture grounded in the principles of equality and collective cooperation between artists, engineers and the proletariat. In a review of the event published in the Nowy Kurier newspaper, Berlewi gave a detailed description of the work of the artists at the congress, who represented widely diverse avant-garde groups, from the French Cubists, Italian Futurists and German Dadaists to representatives of international Constructivism. It was actually the last-named direction in art, which was propagated by Lissitzky, that would shortly become the leading trend in avant-garde experimentation. Berlewi included not only the Russian artist in the group of constructivists he listed in his review, but also Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg, Swedish artist Viking Eggeling, two Belgian artists, Jozef Peeters and Hubert Wolf, and two Hungarian artists, László Peri and László Moholy-Nagy. In the early nineteen twenties, a great many Hungarian artists with left-wing views were forced to leave their country during the White Terror, when Miklós Horthy launched a mass persecution targeting the founders of the revolutionary Hungarian Soviet Republic. During the Düsseldorf congress, they made an appeal, speaking of the task of art, which has to respond to the socio-political challenges presented by modernity. One of the signatories was Moholy-Nagy.

What linked Le Corbusier and Szczuka above all was the fact that they proposed similar solutions for building new residential estates. Just as with Ford’s cars, the result of ‘manufacturing’ homes industrially was intended to be a lower price, affordable for the working class

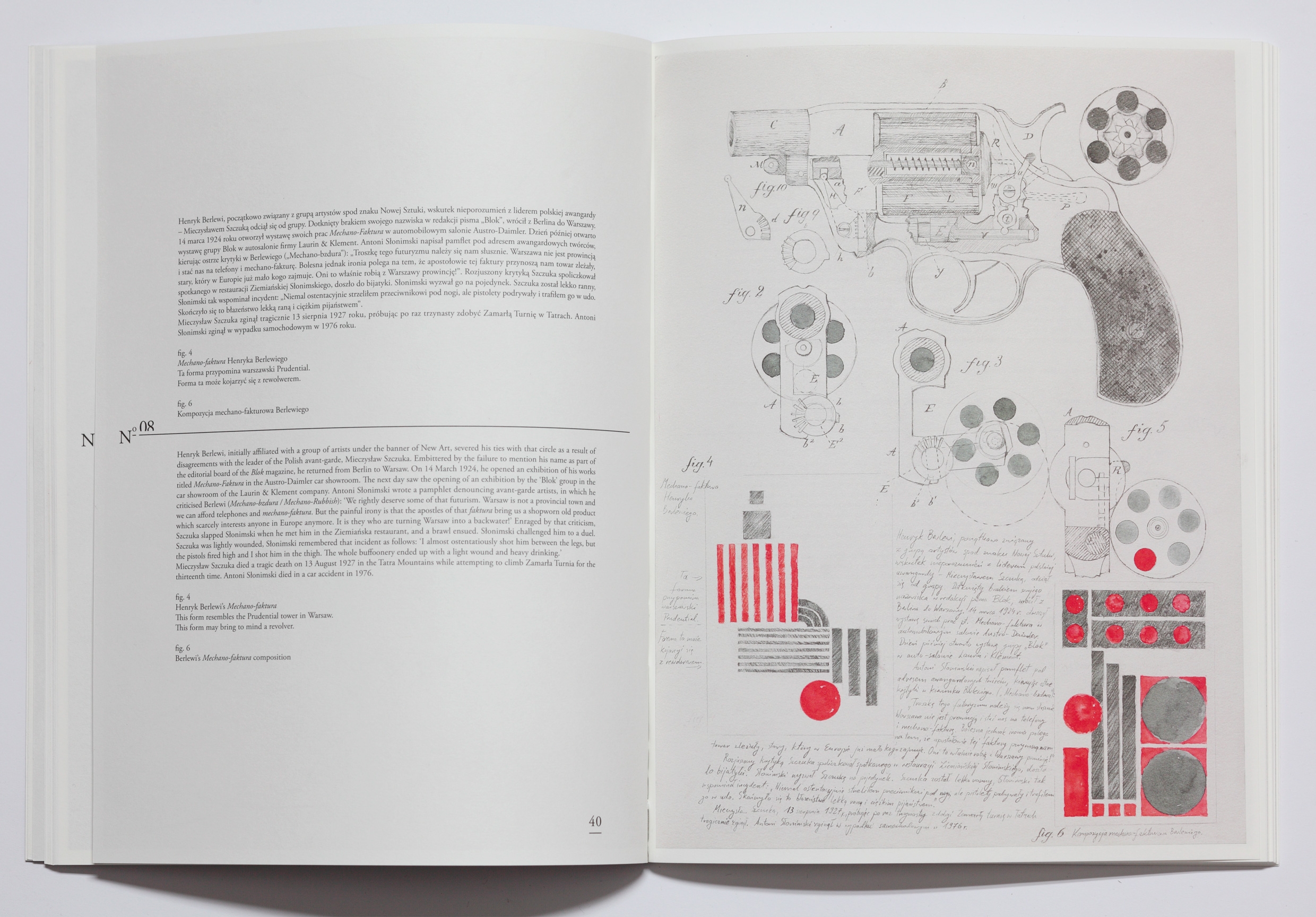

It is interesting to note that, even back then, Berlewi had discerned the constructivist aesthetic in Moholy-Nagy’s works and the Hungarian artist’s name appeared in his review in the company of Western avant-gardists. This was an uncommonly crucial moment in time, when both Berlewi and Moholy-Nagy were maturing and growing towards their future undertakings, which would intensify over the decades to come. In 1923, Berlewi would formulate his Mechano-Faktura concept, which was intended to be a manifestation of Polish constructivism. However, in the end, he never joined the collective activities of the Blok group. Although one of his mechano-fakturas was featured in the first number of a Warsaw journal of the same name, he took no part in Polish constructivist exhibitions. That same year, Moholy-Nagy was invited to teach at the Bauhaus school and his career was bound up with the experiments he carried out within its ambits for several years. Both he and Berlewi exhibited in Berlin together with the Novembergruppe and under the general heading of constructivism.

It is, however, worth detailing certain differences in the two artists’ work. In his mechano-fakturas, Berlewi was interested in emphasising the two-dimensionality of the canvas and the rhythmisation of lines and planes, as well as in juxtaposing simple geometric forms. Meanwhile, Moholy-Nagy was focused on exploring the form of the third dimension not only in painting and graphic art, but also in sculptural installations. In both cases, the intention was for the new language of abstract forms to harmonise with a dynamically changing world and to demonstrate the effects of El Lissitzky’s constructivist experiments. Berlewi thus emphasised the second dimension and Moholy-Nagy, the third. If we add El Lissitzky, who followed Kazimir Malevich in popularising suprematism, then what we evidently have is an exploration of the fourth dimension. Therefore, despite the progressive notions of collective collaboration which were the guiding principle of the Düsseldorf congress, all of the artists mentioned here displayed individual approaches to their own formal experiments. In conducted them, they were moving towards the exploration of three wholly different dimensions.

Note 2. Le Corbusier – Mieczysław Szczuka

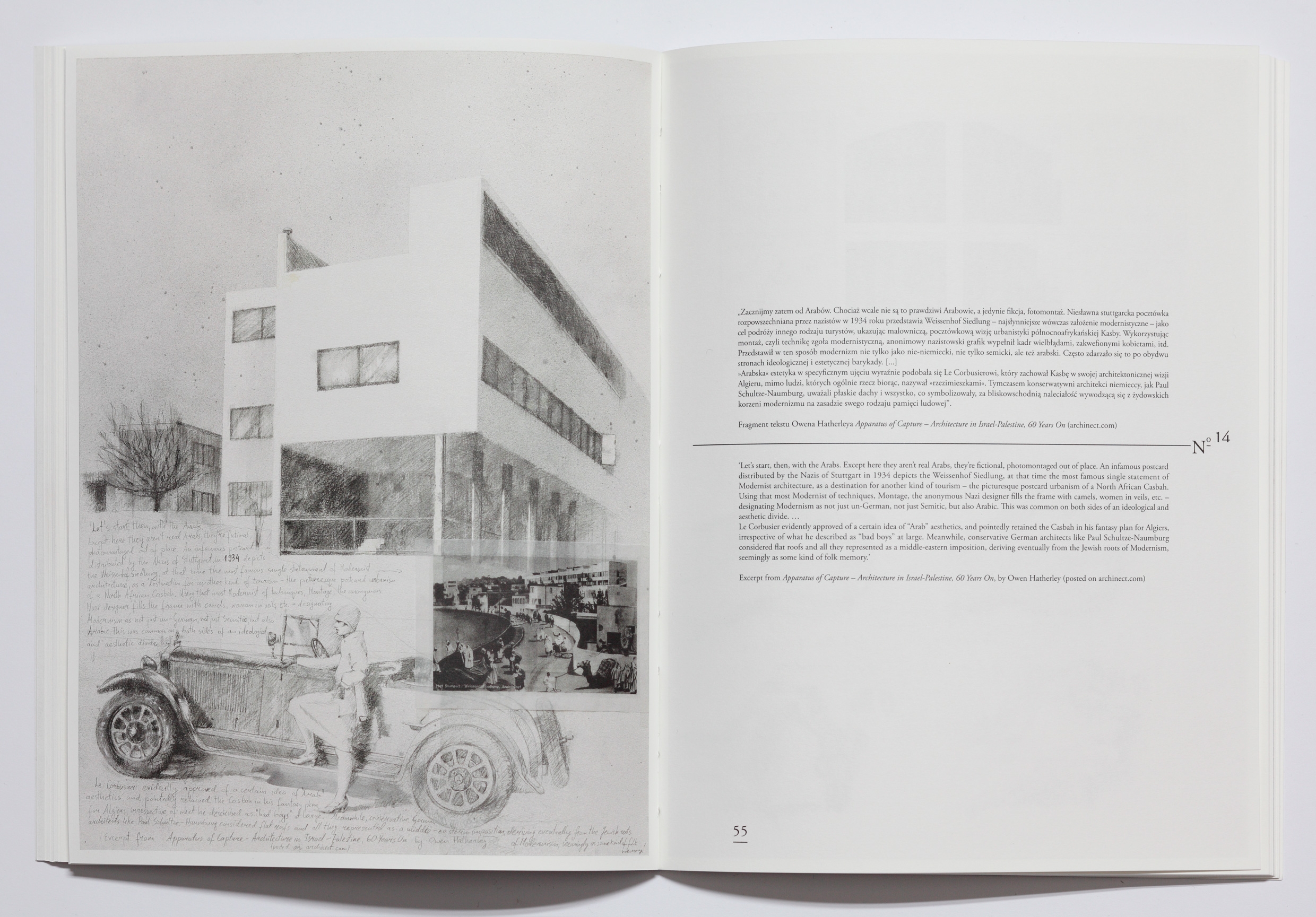

Nowadays, the photo of Berlewi at the Mechano-Faktura exhibition held at the Austro-Daimler automobile showroom in Warsaw in 1924 is one of the most famous shots taken inside an experimental exhibition space and has been reproduced in numerous works on the history of the avant-garde. Artists often portrayed themselves beside cars or behind the wheel in order to demonstrate their fascination with this new creation of technological modernity. Notable examples of this type of portrait include the photo of Filippo Tommaso Marintetti in a Lancia. It was taken not long before the accident which provoked him into writing his Futurist Manifesto. Sonia Delaunay posed in a car in front of the tourism pavilion at the Paris exhibition and, in 1934, Le Corbusier posed in his on the roof of the Lingotto building, which housed the Fiat factory in Turin. Le Corbusier was actually one of motorisation’s most fervent admirers. He designed a house for André Citroën and considered the Lingotto building to be a model for urban planning. In his book of essays, Vers une architecture, he remarked that the factory was one of the most magnificent of industrial spectacles. In the same publication, he also juxtaposed the ruins of Ancient Greek temples with images of automobiles. His conviction was that architecture should move forward to the moment which contemporary motorisation had already reached. Not for nothing did he consider the Lingotto factory to be the model for new conceptions of modernist architecture.

This was an uncommonly crucial moment in time, when both Berlewi and Moholy-Nagy were maturing and growing towards their future undertakings, which would intensify over the decades to come.

His fascination with the car as a technological invention of modernity was something highly typical of avant-garde artists, irrespective of the centres where they worked. It is worth citing Mieczysław Szczuka’s design for an automobile showroom, which was reproduced in the tenth number of the Blok journal. It was based on Le Corbusier’s architectural assumptions, with designs for the windows which were reminiscent of Piet Mondrian’s neoplastic paintings, being restricted to white with black vertical and horizontal lines. The interior of the building could be seen through the shop windows. They revealed a display space not only for cars, but also for the sculptural structures typical of Szczuka’s spatial work at the time. He placed the names of two makes of car on the façade in huge letters; Fiat and Citroën. Szczuka’s automobile shop was never built. His design has never seen profound analysis by scholars of the avant-garde, either. This is despite the fact that it clearly evinces features of Le Corbusier’s and Mondrian’s avant-gardist, neoplastic and architectural experimentation, combining, as it does, the properties of a shop and a space for presenting works of art.

The avant-garde, architecture, the factory, art, new technologies, inventions, commercialisation, consumption, the aesthetics of speed; all these aspects are contained within the symbolism of the automobile. Szczuka never forgave Berlewi for exhibiting his mechano-faktura works in the Austro-Daimler showroom on the day before the presentation of works by the Blok constructivist group, which was scheduled to take place in the Laurin & Clement car showroom. His car shop design went on show in Warsaw, at the 1st International Exhibition of Modern Architecture, together with Le Corbusier’s architectural designs and Gabriel Guevrekian’s design for the Automobile Club Hotel on the Riviera. What linked Le Corbusier and Szczuka above all was the fact that they proposed similar solutions for building new residential estates. Just as with Ford’s cars, the result of ‘manufacturing’ homes industrially was intended to be a lower price, affordable for the working class. At the same time, the ‘mass production’ of architecture would solve a number of social problems. However, in the case of motorisation, a compact car for the people, a car which would reflect the needs of the proletariat, turned out to be neither Fiat nor Ford nor Citroën, but the Volkswagen designed by Ferdinand Porsche.

Paweł Książek, ‘Plates’, courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery

Note 3. Bruno Schultz – Sonia Delaunay

Berlewi’s, Szczuka’s and Le Corbusier’s fascination with cars denoted a sign of equality between the automobile, perceived as a modern invention, an object from the world of consumption, on the one hand and, on the other, a work of art. That sign can also be observed between exhibition spaces intended for artistic products and showrooms, shops and factories. Avant-garde artists very often drew attention to the fact that art was drawing closer to everyday life or, to be precise, that it was actually avant-garde art which was to solve social problems and aestheticise existing reality on the basis of new technological solutions.

One of the most important exhibitions of the first half of the twentieth century was held in Paris in 1925. The cosmopolitan Parisian event hosted bold architectural and interior designs. One of the attractions was Sonia Delaunay’s and Jacques Heim’s ‘simultaneous boutique’. A shop window proved to be the place for showing simultaneous clothes intended for mass production. Delaunay translated experiments in abstract art to the sphere of modern fashion, designing colourful simultaneous fabrics featuring geometric patterns. They enjoyed tremendous popularity in Parisian circles, particular amongst the aristocracy. These were not, after all, the football outfits designed by Russian constructivist Varvara Stepanova and mass produced for the proletariat.

A famous photograph which has come down to us from the Paris exhibition shows two women wearing simultaneous clothes by Delaunay. One of them is sitting in the driver’s seat of a car and the other is standing, gazing sensually into the camera lens. Their clothes blend in with the abstract patterns on the car. They are posing in front of the Tourism Pavilion designed in the modernist style by Robert Mallet-Stevens, not far from Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau. The photo was taken at a distance. However, delving further into the story of Delaunay’s presentation at the exhibition leads to the understanding that, in reality, this is neither a photo of two models nor of the artist herself, as it initially seems to be. The figures are two mannequins dressed in clothes by Delaunay.

In my opinion, Strzemiński’s Seascapes series has much more in common with the experiments conducted by the surrealists Breton recruited than with those carried out by the abstractionists of Cercle et Carré.

The mannequin figure proved to be a very intense theme in the work of modernist artists who perceived the fluidity of human identity in the technologically changing world of consumption. Bruno Schulz’s famous Treatise on Mannequins, written in 1934, looks at the relationship between the commercialisation of life and the higher needs of human experience. Writing about giving precedence to trumpery and cheapness of material, he called for the repudiation of traditional artistic norms, where beauty is contained within harmony of form. He emphasised that the life of matter is simultaneously the assumption, absorption and casting off of forms, the best expression of which is the degraded Crocodile Street in Cinnamon Shops.

Both Schultz and Delaunay were born in parts of the present-day Ukraine and they both came from Jewish families. Scholars of Delaunay’s work are discerning inspirations drawing on her native folk culture with increasing frequency. It is worth emphasising that, alongside the mannequin figure in Schulz’s stories, another pivotal focus of deliberations on the human-object relationship appears. It is the car, understood by the author as a contemporary counterpart to the horse-drawn carriage and a vehicle which can provide both bliss and depravity. The automobile as a creation of modern civilisation gives joy, but it also subjugates people who, in the face of technological development, become more and more like mannequins. In the nineteen thirties, the mannequin became one the most important objects in surrealist symbolism. As an international, avant-garde movement, surrealism was called into being in France by André Breton a year before the Paris exhibition and Sonia Delaunay’s simultaneous boutique display. Breton knew her well, this Ukrainian-French artist, yet she never joined his movement. Nowadays, Bruno Schulz is regarded as one of Poland’s few surrealists.

Paweł Książek, ‘Plates’, courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery

Note 4. André Breton – Władysław Strzemiński

How extensive was the reach of the surrealist aesthetic in Poland? Scholars sometimes recognise Schultz, Witkacy and the Artes group as its literary and theatrical representatives in the first two cases, with the last-mentioned as their counterpart in the visual arts. If we accept that recognition as valid, then it can clearly be seen that this aesthetic, which enjoyed tremendous success in Paris and Brussels, went on to put in an appearance in really rather peripheral artistic circles in pre-war Poland, in places like, Drohobycz/Drohobych, Zakopane and Lwów/Lviv. Surrealism was most certainly not a movement in the vanguard in centres of Polish art such as Warsaw, Krakow and Łódź, in other words, in the large, urban areas where the avant-garde of the nineteen thirties could trace its origins in constructivism and the functional approach. When artist Władysław Strzemiński and poet Jan Brzękowski set out to gather together works by avant-garde artists for the International Modern Art Collection founded in Łódź, the main priority was paintings from the influential Parisian abstract art groups by the name of Cercle et Carré and Abstraction-Création. Strzemiński exhibited with the Parisian abstractionists. The creator of Unism, he was much esteemed in Paris. He himself criticised surrealism as a blind play of instincts and dreams inaccessible to the biological eye. The gaze was essential to his paintings, as was the ability to look and to observe reality as an eyewitness. After all, what he was striving to express in his art was seeing objectively and not subjectively. Subjective seeing represented emotions, sensory feeling and the Freudian subconscious, all of it highly akin to surrealism. Strzemiński believed in taking rational cognition of the world and rational history. The history of art and the history of biological, optic experiences united in a close-knit whole and, as a result, the history of dreams was of no great significance in his aesthetic theories and, in particular, in his Theory of Vision.

A famous photograph which has come down to us from the Paris exhibition shows two women wearing simultaneous clothes by Delaunay. One of them is sitting in the driver’s seat of a car and the other is standing, gazing sensually into the camera lens. Their clothes blend in with the abstract patterns on the car.

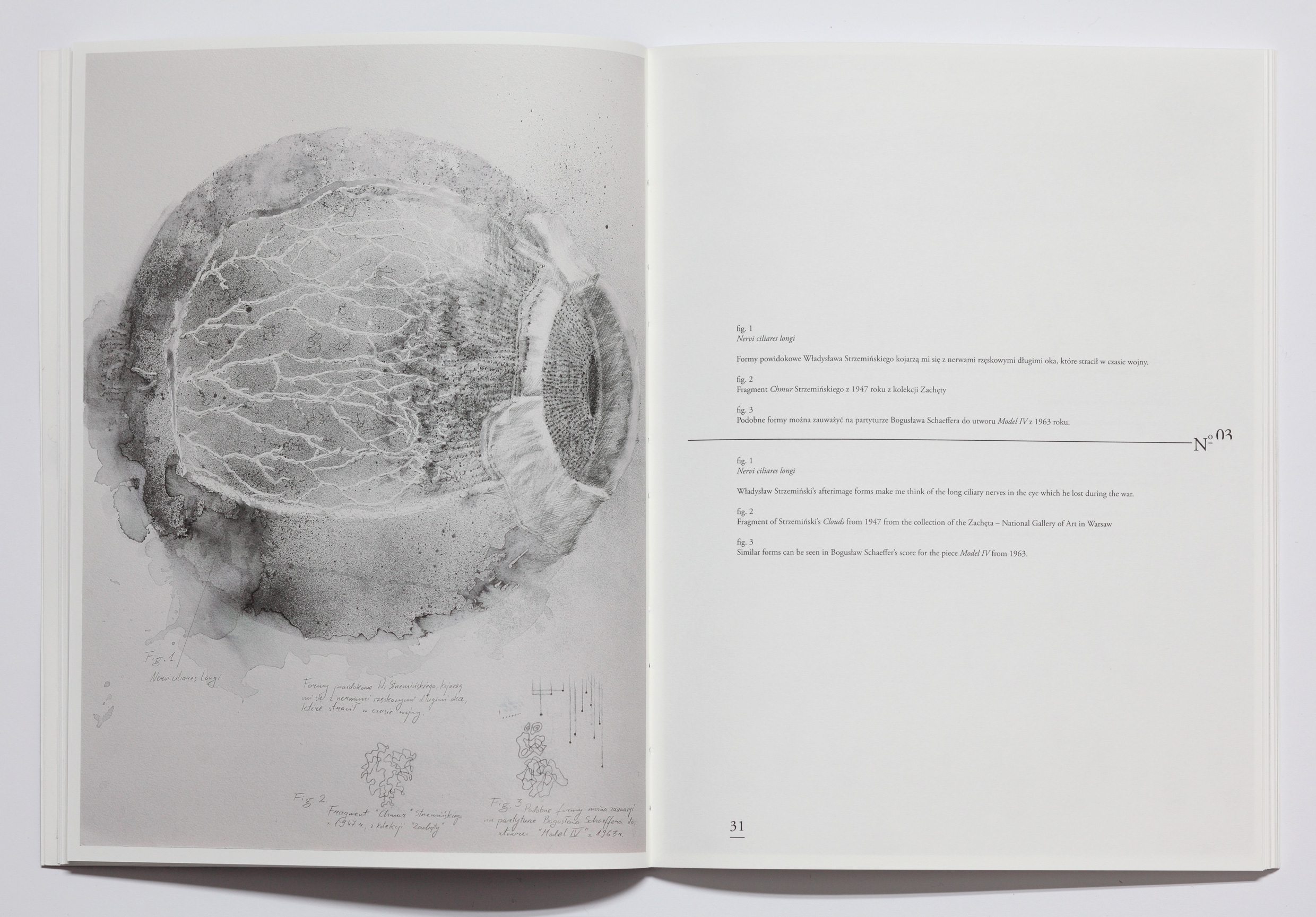

Interested in the physiology of the eye, Strzemiński turned his attention to the formation of after-images, those internal images which remain on the retina after looking at a source of light or gazing at the blinding glare of the sun for a moment. They are momentary ‘traces’ left on the retina by shapes seen by the human organ of sight. His earliest works depicting the phenomenon of after-images include his Seascapes series, created in the nineteen thirties. Although his theoretical deliberations on forms of after-image had nothing in common with surrealism, art historian Andrzej Turowski has very appositely remarked that these biomorphic seascapes were much akin to Hans Arp’s surrealist experiments. This is not about interpreting dreams and their symbolism, but about surreal naturalism considered in the categories of the biological evolution of form and the physiology of visual phenomena.

If we undertake a surrealist interpretation of this series of paintings, then the seascape Strzemiński painted on 2nd July 1934 might reveal itself not only as the outlined contours of after-images, but also as two misshapen human forms. It is possible to discern the figure of a man’s body on the right, with the black contour of the head and the blue shape of the body, and, on the left, a woman’s body, the white shape lower down. Here, the after-images, which initially seemed to be abstract, give the impression of alluding to living, biomorphic human forms in collision with one another. The composition appears to be depicting a kind of conflict between the two sexes in outlined antipathy, with the masculine activity of the blue figure opposite the submissive passivity of the white figure. This kind of relationship was a highly typical motif in the surrealist art defined by André Breton from the mid nineteen twenties. It was, in fact, Breton who was one of the greatest propagators of biomorphic surrealism. The artists he recruited to his group explored a world of living forms. Amongst them were Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy and Kurt Seligmann. In my opinion, Strzemiński’s Seascapes series has much more in common with the experiments conducted by the surrealists Breton recruited than with those carried out by the abstractionists of Cercle et Carré.

Paweł Książek, ‘Plates’, courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery

Note 5: Conlon Nancarrow – Bogusław Schaeffer

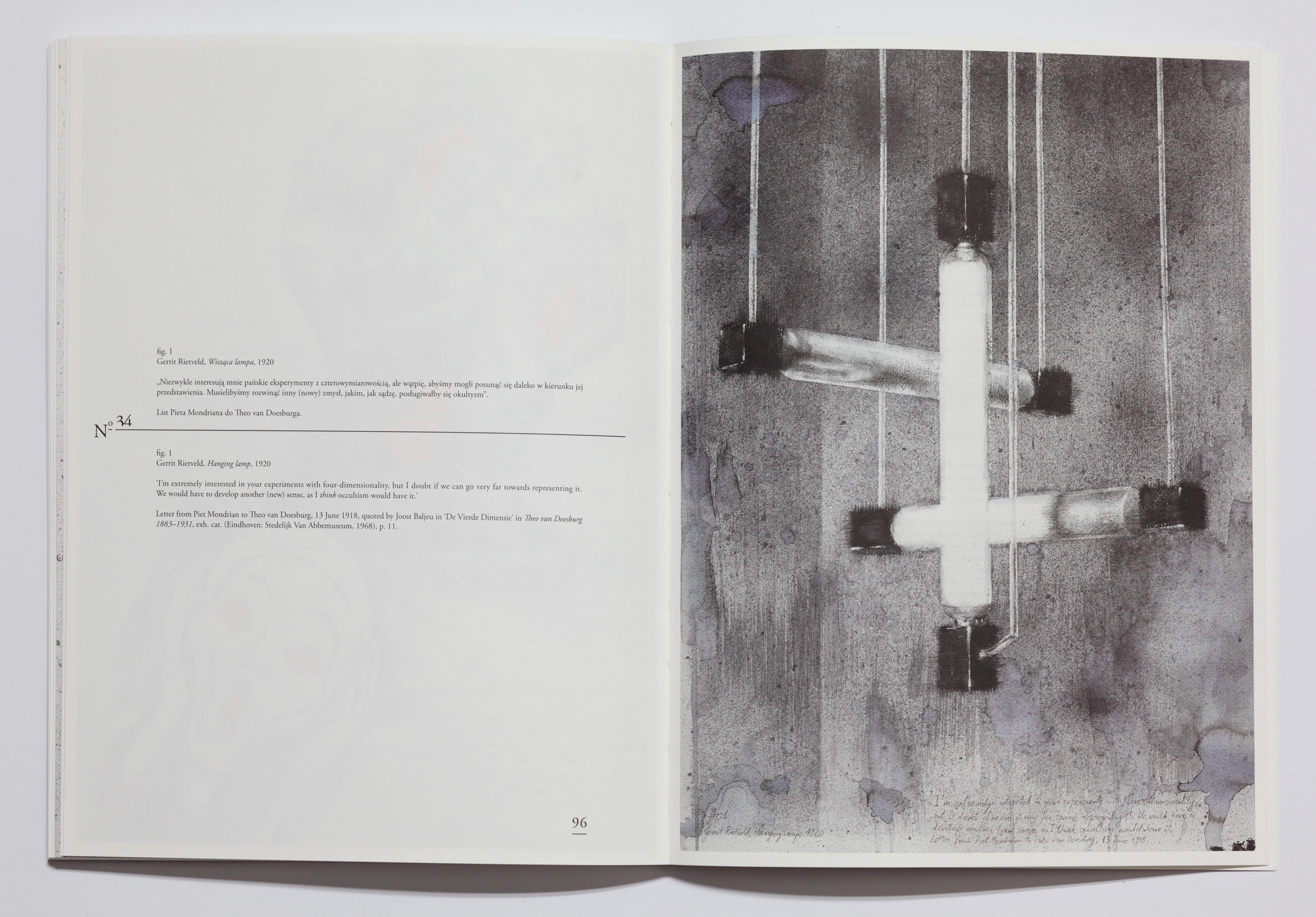

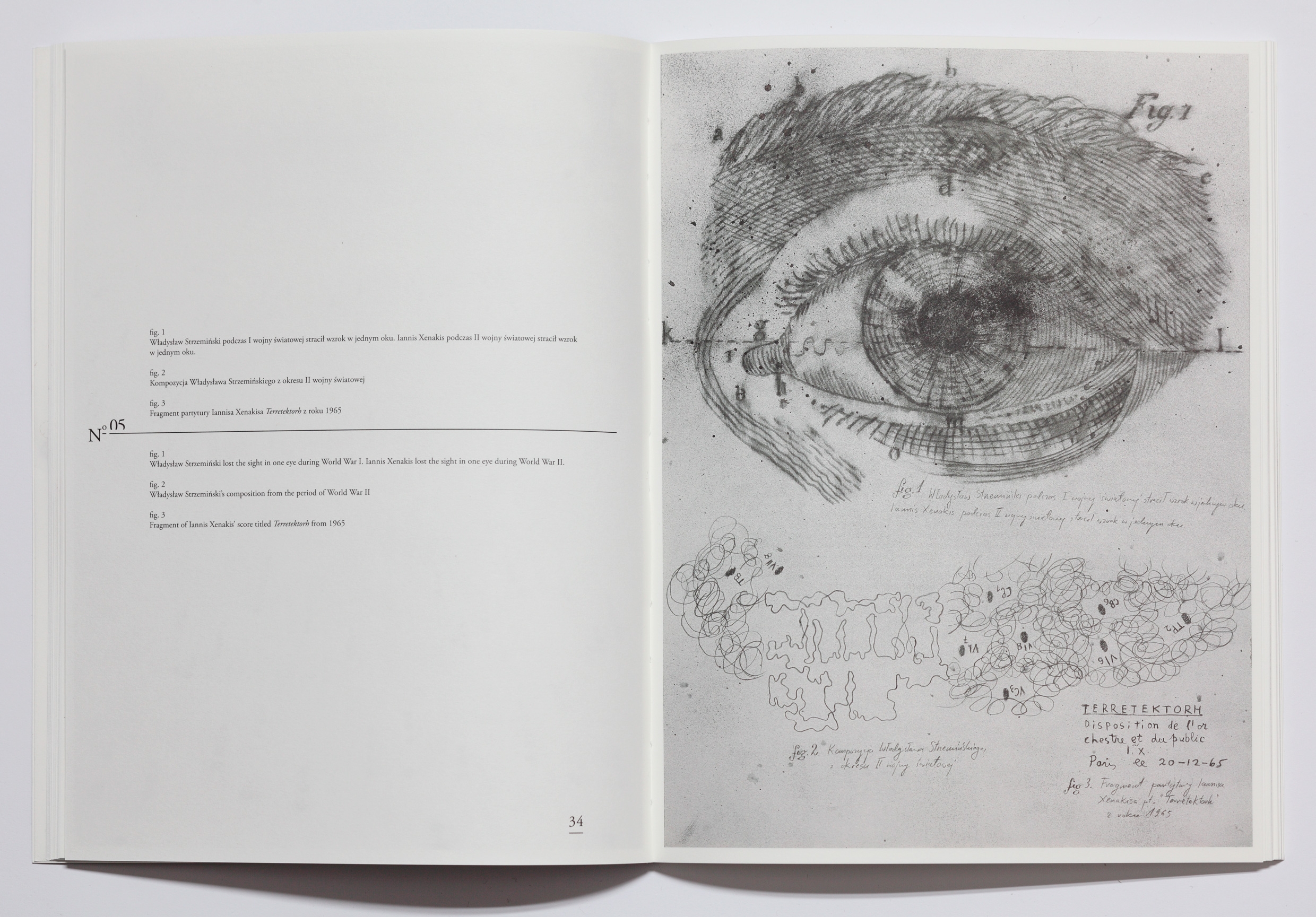

Władysław Strzemiński’s after-image forms make me think of the long ciliary nerves of the eye he lost during the war. There are similar forms to be seen on Bogusław Schaeffer’s score for his Model IV, composed in 1963.

Contemporary music and abstract art are very often closely connected. And that was already true in the first decade of the twentieth century, when Wassily Kandinsky sought an equivalent to the music of Arnold Schönberg in abstract painting and Piet Mondrian was finding neoplastic inspiration in jazz music, beginning with compositions for the foxtrot and moving on to the famous New York boogie-woogie, which was danced to the sounds of bebop.

He reads the moment when one of the central characters issues a warning that the slightest mistake on the part of any of the protagonists will spell absolute destruction to them all as an allusion to a widespread belief in Germany, which held that the catastrophe of that conflict was the outcome of individual errors.

In the second half of the nineteen sixties, Bogusław Schaeffer created an electro-acoustic soundtrack for a biographical film, Władysław Strzemiński, directed by Bohdan Mościcki. The musical experiment, which used panoramic acoustic effects that simultaneously caused aural illusions, is the background for a voice reading Strzemiński’s Theory of Vision. Schaeffer was one of the first Polish experimental music makers who was interested in electronic music and, although musicologists and theatrologists have repeatedly studied his work, it is the cultural studies scholars and art historians who have looked at the visual presentation of his scores, albeit to no great extent. Model IV makes itself manifest as a combination of the most diverse abstract forms, not only Strzemiński’s vibrating lines, but also vertical and horizontal ones cutting across each other and crowned each time by dots. The notation brings to mind the juxtaposition of Moholy-Nagy’s constructions with Strzemiński’s after-images, the geometric solutions of the De Stijl artists and the abstract film experiments carried out by Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling. Those three filmmakers used musical terms for the titles of their experimental works; for instance, there was Ruttmann’s Opus 1, Richter’s Preludium and Eggeling’s Symphonie diagonale (Diagonal Symphony). They sketched the transformation of various motifs and sets of geometric figures on long scrolls which became the ‘scores’ for their films. Abstract film was intended to be a ‘visual music of form’.

One thing of interest when considering this aspect are the shapes on the piano rolls which American-Mexican musician Conlon Nancarrow used to notate his scores. He designed and commissioned his own player piano, a mechanical instrument which plays music notated on perforated rolls of paper. Despairing of the technical capabilities of individual performers, he had decided to free himself of the highly fallible human factor. In the quiet of his workshop he perforated fifty pieces, or ‘studies’, as he called them, for player piano, which he played for a small group of listeners. These works were entirely independent of people.

In contrast to Nancarrow’s experiments, Bogusław Schaeffer’s works make themselves manifest as musical and visual projects which are deeply rooted in the humanities. In this sense, his music and artistic practice was much more akin to Strzemiński and the understanding of art as a phenomenon closely connected to human physiology. To Nancarrow, though, the player piano’s performance was more interesting when the machine itself played something that the person composing the work would never have noticed.

Paweł Książek, ‘Plates’, courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery

Note 6. Leni Riefenstahl and Edgar G. Ulmer

Bogusław Schaeffer was one of the co-founders of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio and the Polish school of electro-acoustic music. It is worth emphasising that it was there, in that studio, in the early nineteen seventies, that Krzysztof Penderecki’s famous Ekecheirija, commissioned by the Organising Committee of the Munich Olympic Games, took shape. At the time, the studio was being run by Eugeniusz Rudnik. After the opening ceremony and raising of the flag, the work rang out in the modern stadium as a song of friendship and peace. A visual record of those games exists in an extraordinarily interesting documentary, Visions of Eight, where eight directors, including Miloš Forman and Kon Ichikawa, shot short films of no more than twenty minutes. Each of the eight films was focused either on a given discipline or on a particular Olympic event. As we can see, the cultural programme for the Munich Olympics, which was created by musicians and artists from all over the world, was both extensive and diverse.

The organisers of the first post-war games to be held in Germany took great care to establish a counterbalance to the politicised ceremonial which was arranged by the Nazi authorities in 1936 and recorded by Leni Riefenstahl in her famous film, Olympia. The film depicted the universal beauty of the sporting bodies of the Aryan race and, at the same time, alluded to the golden age of Ancient Greece and the first games. There can also be no doubt that, nowadays, knowledge about the visual image of the XI Summer Olympic Games is widely drawn from the frames of that film. In fact, Olympia has often served as the basis for studies on the aesthetic aspects of Nazi ideology, where sporting victory and the ideal of the Aryan sports person’s ideal body would play a primary role in the apparatus of political propaganda. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, German filmmaking was largely subordinated to agitational purposes. Meanwhile, like German expressionist art, cinema in the spirit of expressionism, which had predominated film production in the preceding decades, found no favour in the eyes of the Nazi authorities.

Schaeffer was one of the first Polish experimental music makers who was interested in electronic music and, although musicologists and theatrologists have repeatedly studied his work, it is the cultural studies scholars and art historians who have looked at the visual presentation of his scores, albeit to no great extent.

In the early nineteen thirties, there was a significant rise in the popularity of American horror films, where the springboard was sometimes an expressionist work like Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In 1934, and thus in the year that the Nazis seized power in Germany, Edgar R. Ulmer, an Austrian film director of Jewish origin, made a film in the USA. Entitled The Black Cat, it has often been interpreted as a reflection of those grim pages of German history. Jon Towlson, a scholar of classic horror films, has noted that the film speaks allegorically of the dark powers which possessed Germany after the First World War. He reads the moment when one of the central characters issues a warning that the slightest mistake on the part of any of the protagonists will spell absolute destruction to them all as an allusion to a widespread belief in Germany, which held that the catastrophe of that conflict was the outcome of individual errors. In Towlson’s opinion, The Black Cat foreshadowed the spectrum of the enormous tragedy which would begin just five years later as a result of Nazi ideology. Around 1933, a host of emigrants from German-speaking areas had arrived in the USA. Amongst them were makers of horror film productions which were considered to be allegories of the Nazi terror with highly uncommon frequency. The Black Cat also displays an interest in the occult, which was, after all, crucial to the politics implemented by the authorities of the Third Reich.

Shortly after the film’s box-office success, Ulmer decided to work on a remake of one of Leni Riefenstahl’s first films, The Blue Light, made in 1932. He respected her early work, even though he knew that she was the Nazis’ appointed director of fictionalised propaganda documentaries in the spirit of Olympia. Unfortunately, he was unable to return to either Austria or Germany before the war broke out. Filming of his remake of The Blue Light was scheduled to take place in Switzerland in 1948. In the end, though, it never came to fruition.

Paweł Książek, ‘Plates’, courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery

Note 7. Max Schmeling and Rudolf Belling

To a large extent, what defined cinema culture in the nineteen thirties was the relationship between the propagandist kitsch which emerged from Riefenstahl’s films and the fictionalised kitsch or, to be precise, campness, which emerged from expressionist films, on the one hand, and American B movies in the horror genre on the other. This is clearly evident when German and Hollywood productions are juxtaposed. Understandably, kitsch and campness also predominated in romantic films, as a German production, Reinhold Schünzel’s 1930 Love in the Ring, also known as The Comeback, bears out. It tells the story of a boxer called Max and his sweetheart, Hilde. As a result of the publicity surrounding his victories, Max becomes enormously popular. Then a beautiful woman seduces him. He is faced with an emotional dilemma, not knowing which of the two women he should stay with for good. In the end, as the final of the German championship is in progress, he decides to return to his sweetheart. The film, which proved to be quite a success, actually featured a real-life boxer and darling of the German public, Max Schmeling. After winning the European heavyweight championship, Schmeling went to America to develop his career.

In one of his letters to Piet Mondrian, he maintained that, despite intense experimentation, he was unable to convey the equivalent of the fourth dimension in visual art. He also emphasised a phenomenon which might prove to be vital to changing our perception, in other words, the occult.

In the nineteen twenties and thirties, his body was one of the most recognisable models for the masculine figure in German visual culture. At that stage, the German and European champion was regarded as an icon. He was an idol, the first German celebrity in the contemporary meaning of the word. He posed for portraits, including George Grosz’s famous Max Schmeling, which shows him outside the ring, gloveless, but poised to fight. The sculptor Rudolf Belling immortalised him in much the same pose, depicting him in a defensive position, waiting to take a blow. His guard is down, his fists are clenched and his muscles are taut. He is inciting his opponent to attack. His face betrays a sports professional’s intense concentration.

It is interesting to note that the sculpture in question, Belling’s Max Schmeling, created in 1929, was included in a propagandist exhibition, Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung. During the event, which was held at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich in 1937, the Nazi authorities glorified the spiritual beauty of the German people. At exactly the same time, Munich was also hosting the Entartete Kunst exhibition was showing other sculptures by Belling, such as his Triad and his Brass Head (A Portrait of Toni Freeden), as an expression of the psychological degeneration of artists and a sick, phantom imagination. The story of these two Munich exhibitions in 1937 bears witness to how very ambivalent the selections made by the Nazi officials were. They made no move to condemn an entire oeuvre once they had decided that the artist in question created works which would fit their own agitational narrative. Schmeling was an unquestioned hero of Germany. When Hitler came to power, the boxer’s victories had become an even more important tool of Nazi propaganda and he himself was the ‘face’ of the new authorities and the new, totalitarian system.

Paweł Książek, ‘Plates’, courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery

Note 8. László Moholy-Nagy – Henry Berlewi

Rudolf Belling was one of the most recognisable sculptors of the Weimar Republic era and sport was one of the most popular motifs undertaken by German artists during the interwar years. Sport also played an important role in the Bauhaus milieu. The students attended athletics and gymnastics classes which were run under the direction of famous teachers and practitioners. The topic of physical culture permeated the artistic projects. László Moholy-Nagy’s famous photomontages can serve as an example. They featured cut-out photographs of sports people in compositions with other photos, most often with a political theme.

Not long after the Bauhaus had been closed down by the Nazi authorities in 1933, Moholy-Nagy emigrated to Great Britain. Little known to this day is the fact that he spent some time preparing to film a documentary about the XI Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, not on behalf of Nazi Germany, but for a British film agency. His wife’s memoirs tell us that he made his way to Berlin in August 1936, but left again after one of his former Bauhaus students, clad in the uniform of the SS, greeted him with a Nazi salute. In the end, Moholy-Nagy refused to make a film about the games, given that the context would be that of Nazi ideology.

In the nineteen twenties and thirties, his body was one of the most recognisable models for the masculine figure in German visual culture. [Schmeling] was regarded as an icon. He was an idol, the first German celebrity in the contemporary meaning of the word.

It was no random chance that Nazi Germany received the right to organise the 1936 games. Pro-fascist sympathies were growing within the sports policies of the International Olympic Committee. When Hitler came to power, Baron Pierre de Courbertin, known as the father of the modern games, responded with delight to the fact that the authorities of the Third Reich would be responsible for the XI Olympic Games. The five Olympic rings, symbolising the fellowship of the five continents, diversity and peace, were appropriated by Nazi ideology.

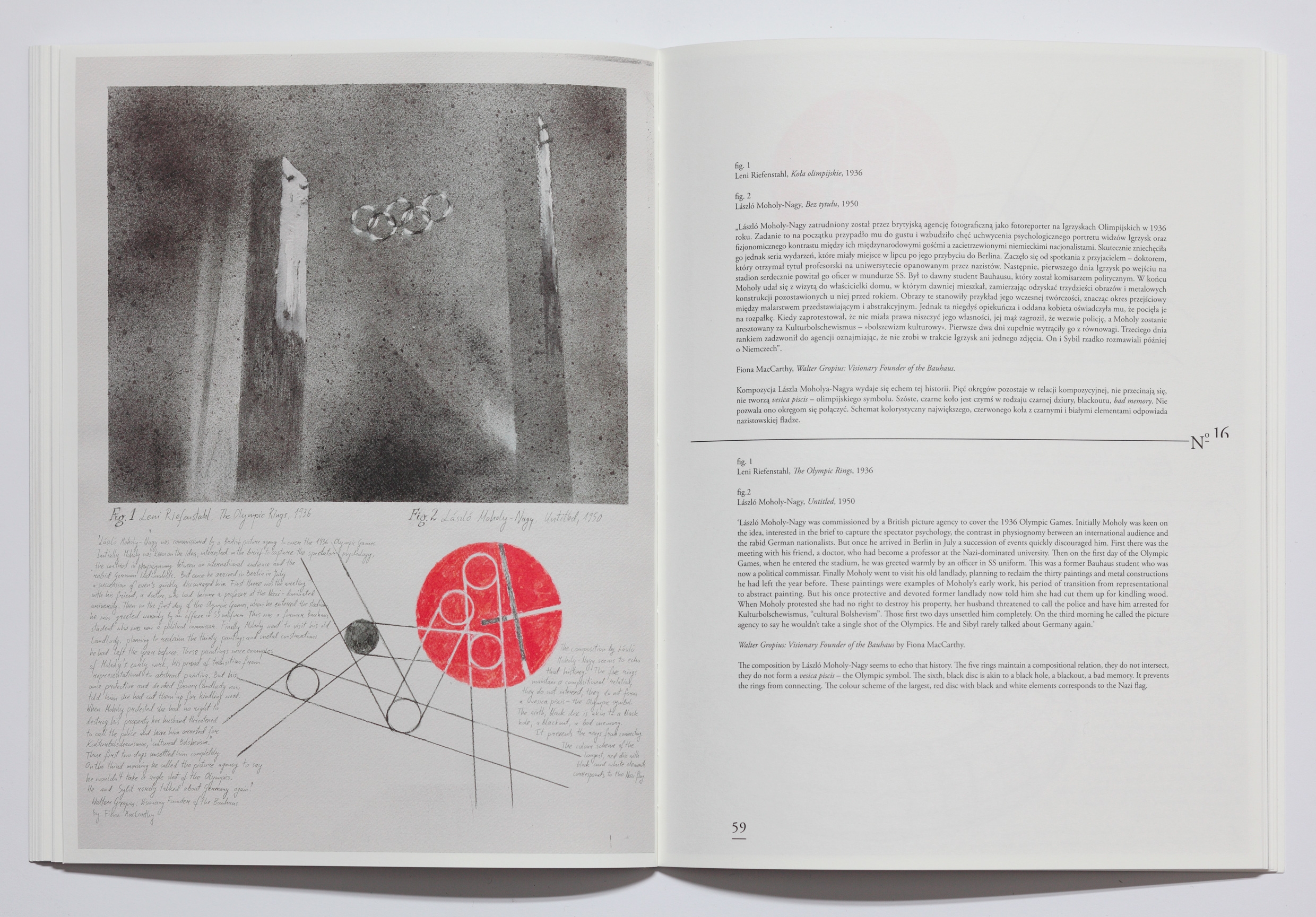

Moholy-Nagy’s Composition of 1950 seems to allude to the history of the Nazi Olympics and to be a critical look at that dark page in the history of the International Olympic Committee’s sports policy.

The five rings maintain a compositional relation, they do not intersect, they do not form a vesica piscis – the Olympic symbol. The sixth, black, disc is akin to a black hole, a blackout, a bad memory. It prevents the rings from connecting. The colour scheme of the largest, red disc with black and white elements corresponds to the Nazi flag.

At the same time, the colour scheme also corresponds to that of Berlewi’s mechano-fakturas, where the artist set out to operate with only three hues; black, white and red. In an interview, Berlewi emphasised that sport had always interested him and that he even created posters for Israel’s Maccabi football club.

His work and Moholy-Nagy’s can be seen to differ if we consider the question of their approached to exploring dimensional data. Berlewi emphasises the second dimension in his abstract works, while Moholy-Nagy emphasises the third. Theo van Doesburg, ‘the Dutch constructivist’, as Berlewi dubbed him, was also interested in this aspect. In one of his letters to Piet Mondrian, he maintained that, despite intense experimentation, he was unable to convey the equivalent of the fourth dimension in visual art. He also emphasised a phenomenon which might prove to be vital to changing our perception, in other words, the occult.

Translated by Caryl Swift

The text was published in Plates, an art book by Paweł Książek accompanying his exhibition at the Foksal Gallery in Warsaw, 5 February – 26 March 2021.

Imprint

| Artist | Paweł Książek |

| Exhibition | Plates |

| Place / venue | Foksal Gallery, Warsaw, Poland |

| Dates | 5 February – 26 March 2021 |

| Curated by | Katarzyna Krysiak, Przemysław Strożek |

| Photos | Paweł Książek |

| Publisher | Mazowiecki Instytut Kultury |

| Published | 2020, Warszawa |

| Website | www.galeriafoksal.pl |

| Index | Foksal Gallery Katarzyna Krysiak Paweł Książek Przemysław Strożek |