On November 25, Galeria Labirynt in Lublin, Poland opened two exhibitions dedicated to the Russian war in Ukraine: the solo exhibition “Repeat after me” by Open Group and the collective exhibition “I dreamed of beasts,” curated by Kateryna Iakovlenko and Halyna Hleba, organized by Artsvit Gallery (Dnipro).

Open Group is a Ukrainian artistic collective that has been active since 2012. Organized in Lviv by six artists from the west of Ukraine, they were focused on invisible topics, commonness, and coexistence in time and space. Open Group has presented its works in many international platforms, including the Venice Biennale. In 2019, the collective became the curators of the Ukrainian National Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The exhibition “Repeat After Me” consists of one video installation, created in 2022, which reflects the experience of persons displaced by the Russian war in Ukraine. Ukrainian art researcher and curator Kateryna Iakovlenko explains why this artwork is essential. Being herself a temporarily displaced person because of the war, she touches on displacement and coexistence, which becomes symbolic in the context of sharing the space of one gallery.

How to talk about the cruelty of war by not showing the destruction of buildings, bombed bridges, and crashed military equipment? How to convey through artworks feelings that can help to copy the individual traumatic experience of war, to show the collective experience of a common struggle, the long and almost exhausted term expectation of a father in the war, or the hope to come back home after de-occupation of the city after eight years of its annexation? Is there a way not to reproduce the visual representation of war through ruins and death, but to show fragility, sensitivity, fatigue, hope, love, and struggle through imagery that stirs the imagination? How to make visible the invisible human experiences and feelings? Perhaps the way is to look more deeply at people’s everyday struggles and resistances and give them a voice to speak.

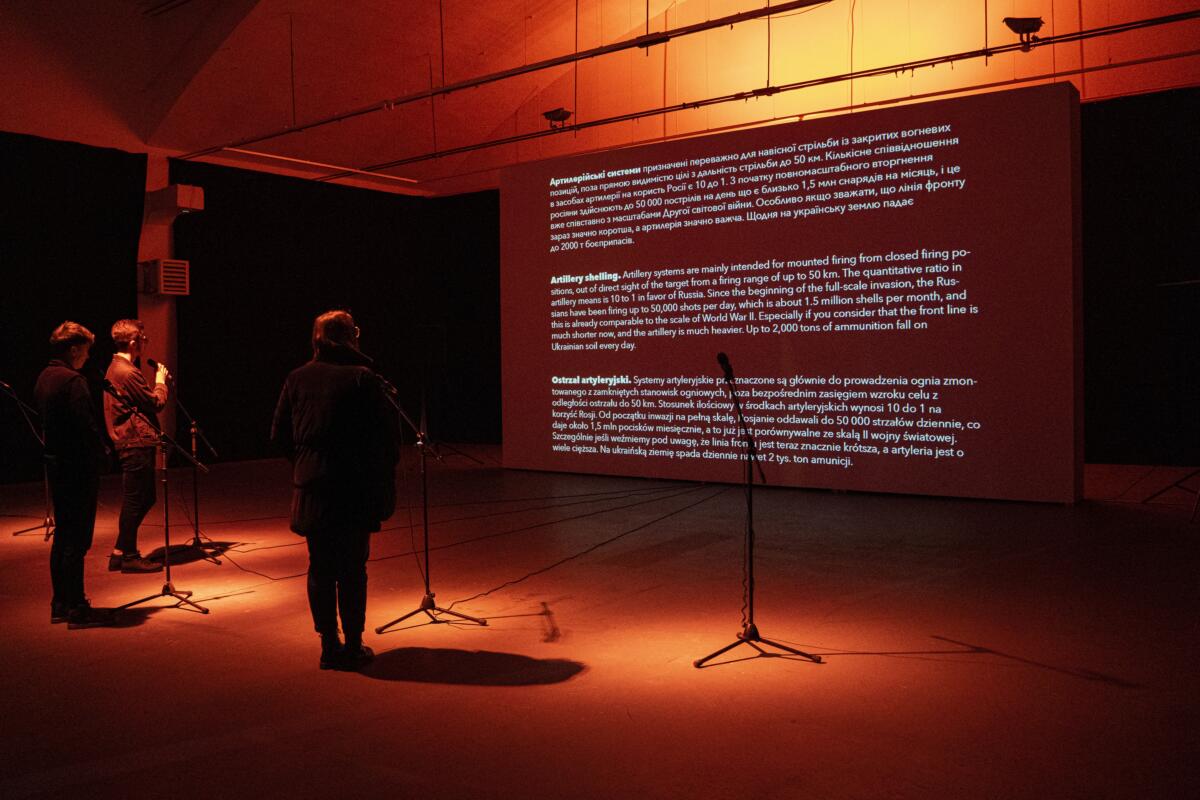

Ukrainian artistic collective Open Group opened a new exhibition at Galeria Labirynt entitled “Repeat after me.” This is an almost 16-minute video which features forcibly displaced Ukrainian people from different regions of the country’s east and south who are currently based in Lviv. They left behind burning bridges and their own houses. In this video installation, these people are talking about their own war experiences, but not in an obvious way. In these short interviews, there is no in-depth analysis of the situation or detailed testimonials of escape and survival. Instead, these people reproduce the sounds of rockets, sirens, and military weapons that the Russians used against them, the sounds they have heard and have experienced personally. The video and installation are formatted like karaoke, so everyone in the gallery can repeat an air raid signal, the sound of shelling, or various types of weaponry. And just beneath the surface, something else is hidden; the same invisible experience of loss, pain, and dignity.

In the almost nine months of full-scale invasion, practically all Ukrainians have become military experts with the ability to distinguish the sound of a fighter jet from that of an Iranian drone. Sound becomes the leading indicator of whether a person is in danger: by strength, intensity, and tone, it’s possible to reconstruct the events happening outside of the buildings. But these relationships with sound are also changing everyday. For example, if earlier, the sound of an airstrike alarm preceded explosions, shelling, or strikes, today, the Ukrainian air defense systems may not activate in time because Iranian drones fly lower and may not be noticed in time.

In the history of art, sound as a form of voice directly refers to agency and political power; it is about political subjectivity and the power of individual experience, which was often silenced and oppressed. For many Ukrainians this occurred through song; songs referring to traumatic and oppressed historical and cultural memory transmitted through words, cadence, and tone, from one generation to another. When Ukrainian culture was suppressed by Russia, traditions and culture were shared precisely through songs sung during family feasts.

Both sound and song are combined in the work of Open Group. It is not about war as geopolitics and the struggle for resources; it is about the everyday violence which touches every citizen directly. It is difficult to imagine what songs will be passed on from one generation to another if the sounds of explosions and shelling continue to drown out the voices of various communities and vulnerable groups.

What does loss consist of, and what is the most painful thing to lose? It’s not even that one won’t be able to make tea like one used to; it’s that the kettle was left in the fire, along with all other personal belongings. It means nothing is left. No favorite books or records on the shelf. No shop with cigarettes on the corner. No park where one would walk the dog. The video features mostly people of an older generation, women in their fifties, and men in their sixties. It is crucial to understand that for Ukraine, this generation has seen many things: they were born during the Khrushchev Thaw that followed censorship and subsequent liberation, Chernobyl, the student strike in the Autumn of 1990 followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Ukrainian independence. They also survived the economic crisis of the early 1990s and experienced two civil revolutions, one in 2004 and the second in 2013. This generation should be preparing for a peaceful old age, saving money for retirement, gardening, or raising children and grandchildren. But instead, today they are first and foremost survivors of war. And now in their 60s, their lives start again, from scratch. In one hand they hold pills to combat their failing health, in the other they hold the key to an apartment bombed by Russians. These people never learned how to properly arm or defend themselves, or to use military weaponry. They did not follow each UN meeting and typically did not know much about foreign policy; they were engaged in household chores and caring for their relatives. Today, their expertise lies in something else, a knowledge they did not seek.

“Repeat after me” vividly illustrates the reproduction of violence and imperialism which Ukrainians have faced for many centuries through the oppression of language and culture by the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and today, the Russian Federation, which deports people from occupied parts and settles in these lands, imposing its own understanding of culture, completely destroying what came before. Despite the call to “Repeat after me” the sounds of military equipment and warning sirens in reality demands the opposite, to stop the war and reproduction of violence. This artwork has become a solid and powerful manifesto against any imperialism.

Open Group was founded in 2012 in Lviv by artists Eugene Samborsky, Yuriy Biley, Anton Varga, Oleg Perkovsky, Pavlo Kovach, and Stanislav Turina, only three members (Varga, Biley, and Kovach) remain. All live in different cities: New York City, Berlin, Wroclaw, and Lviv. But their interest in ordinary life and invisible connections between communities, and the problems they face (like migration, memory, etc.), always remain a common thread. For Open Group, a collective experience and coexistence between generations that no longer exists and those currently living are critical. Lack of connection between artistic generations is also the result of long-term Russian tactical influence, as the collective experience was eroded through reforms, censorship, and the resettlement of people (or just plain deportation). For example, these connections between wars are shown in Open Group’s work “Backyard” (2015), which consists of re-installation and architectural mock-ups. This work tells the experiences of two women – Filomena Kuryat and Svitlana Sysoeva – who both lost their homes as a result of war. The first as a result of World War II and the second as a result of Russian aggression against Ukraine. The architectural models represented the lost houses of these women, recreated in detail. That same year, Open Group implemented another essential project in the context of the war through their performance and video work “Synonym for ‘wait’” (2015), during which surveillance cameras were installed in the homes of Ukrainian soldiers. With the families’ permission, the surveillance camera livestream from the residences of Ukrainian soldiers’ front doors were streamed to the Ukrainian national pavilion during the Venice Biennale. During the Biennale, Open Group members waited for the moment when the soldiers returned home, and refused to take food until that moment came. All day and all night during the Biennale, they were sitting in front of the monitors watching nine screens with the hope that one day the image of the closed door would be replaced by a black screen with the text “returned home”.

The work is about being present; about hoping, sharing, and believing in a better end. Indeed it is challenging to describe how waiting looks, smells, and feels, especially for people who never stood in this position. However, what is essential in these works is not a desire to call for stability and hope for the return of loved ones, but the possibility to evoke empathy in others who have never walked the same path and hopefully never will. Thus, Open Group’s work is not about recreating the same feelings and exact emotions that a family of soldiers or displaced people experience, but rather it is about sharing empathy and support. About solidarity with someone who is in this particular need. It is about a common space for relief.

Today’s shared experience of war, when the entire country and its people have suddenly found themselves both active witnesses and participants in the events of war, cannot be pushed aside. It is important that people have collectively refused to be victimized and have spoken out loud, in unison, about the need for accounts from their own voices, their particular political and cultural positions, and their need to stay in the country despite the loss and pain, which does not subside. But this is also about our hope, which is growing. This experience is a collaborative practice of presence, which is the most powerful gesture that we have seen in recent years.

How does one convey the experience of war through art during a brutal war? How is it possible for art to evoke anything close to such a powerful experience? It occurs not through image, but through sound; the sounds of resistance, sung by the people who face this oppression.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Exhibition | “Repeat after me” |

| Place / venue | Galeria Labirynt |

| Dates | 25.11.2022 - 05.02.2023 |

| Curated by | Waldemar Tatarczuk |

| Photos | Bartosz Górka, Emilia Lipa, Open Group |

| Index | Anton Varga Artsvit Gallery Bartosz Górka Emilia Lipa Eugene Samborsky Galeria Labirynt Halyna Hleba Kateryna Iakovlenko Lublin Lviv Oleg Perkovsky Open Group Pavlo Kovach Stanislav Turina Ukraine Waldemar Tatarczuk Yuriy Biley |