The Berlin based Transmediale festival is for many years an explicitly politically engaged event. Although it focuses on media art and digital culture – or maybe simply because of that fact – its curators see the entanglements of technology, its devilish use as tools of oppression and control, but also possibilities of hope and building a better future. If you are an admirer of autonomy of art, keep out of the festival venue, Haus der Kulturen den Welt. The neighborhood of German Chancellor Office, Bundestag and historical Reichstag seems to be significant.

In this spirit of engagement and taking clear and distinct critical positions, curators invented an extraordinary opening ceremony. Instead of boring talking heads, officials and distinguished guests, sending their thanks and regards, audience was supposed to see and hear political manifestos and calls for action. That was, at least, what I thought after reading the festival schedule, but I fell asleep numerous times (forgive me the night spent on a bus) during the first speeches by Marie Luise-Angerer, media studies professor at the University of Potsdam, and Bernd Scherer, director of the HKW. Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t say a bad word about those traditional opening lectures-speeches, if it wasn’t for term “rally” in the title of the event. Okay, maybe it indeed reminded me of some recent rallies I attended in Poland, but certainly not those which had any potential of being successful in their postulates. They may have contained some valuable diagnosis and philosophical references, but not an imagined vision of the future.

Fortunately, I was awakened instantaneously by Alex Foti’s anticapitalist and antifascist rap. Maybe the Italian activist and researcher of precariat lacked the abilities necessary to make a hip-hop career, but at least he seemed true in what he said (and funny in the way he did it). Most of the following speakers (in one way or another) tried to continue the manifesto-performative attitude: Marc Garrett’s presented the updated version of “Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England” from 1649, addressed to Google and other corporations privatizing the internet, Nina Power proposed unlearning and decapitalism (connotations with decapitation unknown), while Penny Travlou added some feminist threads to the discussions – all culminating in the most performative piece of the evening, by an unclear entity called Goo Goo Muck Analytics and someone called Sergey Schmidt (connotations with Google co-founder Eric Schmidt confirmed).

Those two anonymous persons, dressed up in white protective suits covering their whole bodies, where representers of an initiative named plainly: “Fuck of Google”. As it seemed, the American corporation was probably the most hated figure of the opening event (what happened to Apple and Facebook?), but in this case, the resistance and critique was more focused and down-to-earth than in previous speeches. This time it concerned building a new Google campus in Berlin, specifically in the famous Kreuzberg district, which has become gentrified in recent years even without Google. Dressed up, wearing also animal masks and holding flowers in their hands, Goo Goo Muck really looked like the fight with tech giant might be not only morally appropriate, but also good fun. However we needed a cold shower of realism from Jilian C. York, writer and activist, working for the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Even if we acknowledge that social media are capitalist, misogynistic bastards, people we try to reach with the right message are out there, paradoxically often on social media. So what now? Pragmatism instead of utopian thinking? Maybe yes.

You may have wondered why I devoted so much words to the opening part of the festival. The answer is simple: Transmediale is an event that bounds theory, art and activism. In this light, it is hard to not associate the activities of speakers with art, or just add #postartistic to them. However, there is of course more pieces we could far more easily call art in a more traditional way. The first of such works to notice was visible just after I entered the Haus der Kulturen den Welt. It was an installation by Nick Thurston, a British artist self-described as “the author of two books, one chapbook, one pocketbook, and co-author of two more pocketbooks.” Yes, he certainly works with words.

Even if we acknowledge that social media are capitalist, misogynistic bastards, people we try to reach with the right message are out there, paradoxically often on social media.

His piece in Transmediale was entitled “Hate Library,” which was first produced for last year’s exhibition in Foksal Gallery in Warsaw. The installation focused on one of the most dangerous political trends in recent years – the global rise of nationalism – showing that it is not so recent after all. Screenshots from unspecified online forums, which covered the inside walls of an open, rectangular, u-shaped construction, depicts threads and topics from 2007 – ten years ago, before the financial crisis, Brexit, and Trump. What Thurston’s piece seemed to show was the absurd yet real unionizing and networking of international nationalistic groups, in forums where they are having conversations about supremacy, conspiracy theories and glorifying war heroes and criminals.

The work was not visually entrancing, but it didn’t have to be, or maybe it should not have been. Such understanding corresponds perversely with the Transmediale 2018 main theme: “face value.” Thankfully, visitors at HKW were not overwhelmed with works interpreting the given subject in a straight way, but rather as a suggestion to dig deeper and not take everything as it seemed to be. The mentioned minimalism of Thurston’s work is repeated in the central part of his work where about a dozen stands were located, resembling those used by orchestras or choirs to place notation and text. In this particular case, songbooks are laid together with compilations of screenshots, this time very recent, and segregated according to nations. The circular arrangements of stands created a feeling of wicked community reading nationalist bullshit, this time in your mother tongue (every book was in different national language), looking at people of different nationalities and colors, doing simply the same.

The motif of face from the festival’s theme appears in a literal way only in the second independent work, a series of thirty 3D-printed faces produced by the American artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg. Spectacularly hanging down from the ceiling in relatively huge room full of light, they were not only visually appealing, but also linked many threads present at the panel discussions and in the critical digital culture discourse in general – biopolitics, facial recognition, preemptive policies, shrinking privacy and consequences of whistle-blowing. The sculptural shells/mask were thus at first made to imagine the look of Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning, who revealed secret US army cables relating to the Iraq War to Wikileaks.

“A Becoming Resemblance” is an iteration to a previous, more disturbing work by Dewey-Hagborg, in which the artist collected chewing gum and cigarette butts from the subway and streets of New York, only to extract DNA from them and, in cooperation with a bio-tech company, to create visualizations of the hypothetical look of the chewers and smokers. While it seemed as creepy as a Black Mirror episode (yes, they actually did that in the last season), the technology is not so advanced after all. This, paradoxically, allowed the artist to allow some more universal questions to emerge. The portraits on show illustrated an interview with Manning after her sex-change that took place during imprisonment and while there was an official ban on taking photographing her. Through a lawyer Dewey–Hagborg sculpted these portraits from her DNA. However, the work is not only the illustration but due to a lack of precision it must be manually adjusted in the process thereby also invoking the gender transformation process itself. In doing so, I saw the work as touching an old debate between naturalists (biological and genetic) with those of social and cultural determinism.

The main exhibition hall, dark and depressing, contained an exhibition called “Territories of Complicity” that took the notion of the “free port” as it’s starting point. Free ports are special economic zones the global financial elite use as tax free warehouses for art storage. Although theoretically and ideologically interesting, the concept lacked architectural and practical reference points. It was sometimes simply inconvenient to look at some works, and other were too rich in elements for the relative small space (e.g. Zach Blas’ “Contra-Internet” or Femke Herregraven).

Lisa Rave uncovered surprising links between tribal communities of indigenous people of Papua New Guinea, and modern technocratic societies.

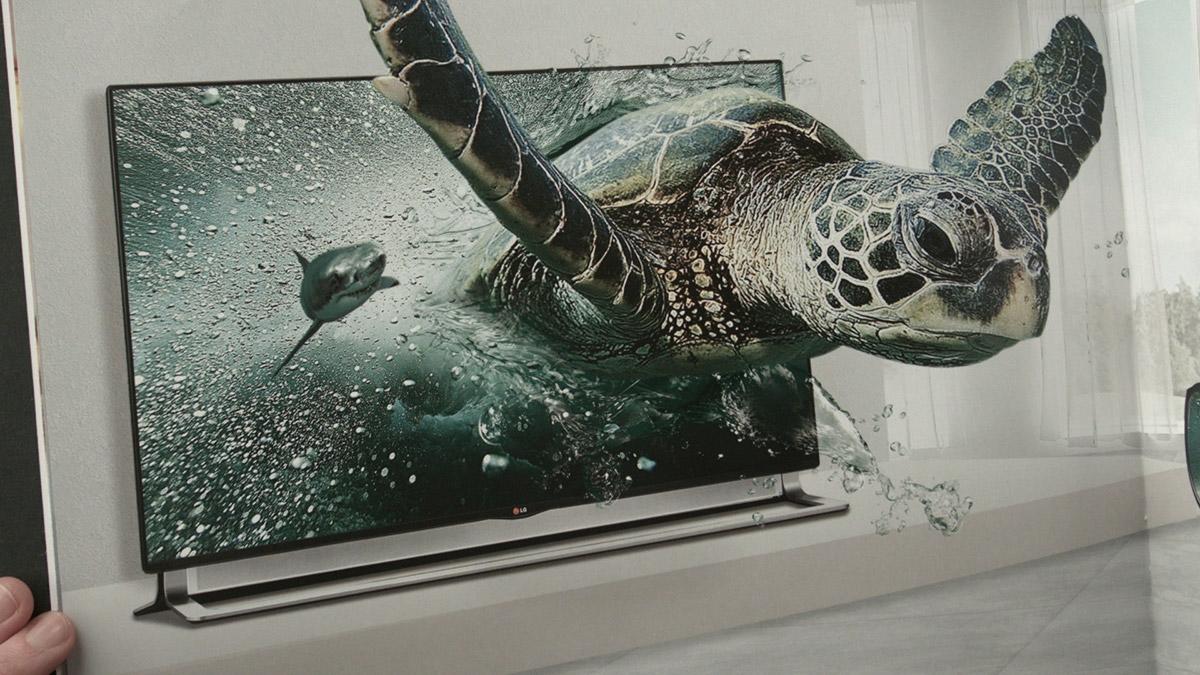

However, I was ready to forget about those problems, since the curatorial selection seemed to stand on a high level, and, at least in most cases, the research conducted by artists to produce their works impressive. Take “Europium” by Lisa Rave as an example, my personal favourite among the works. In her film—a work between documentary and video art—the director told the story of europium, a chemical element, filtered through the story of colonialism. In it, vivid colors can be seen on the screens of TVs, computers and smartphones. Rave uncovered surprising links between tribal communities of indigenous people of Papua New Guinea, and modern technocratic societies. It was not an eternal return of some kind, but rather a new materialistic loop that existed between sea shells treated as currency by Papuan communities and Euro banknotes, using the fluorescent chemical element europium, extracted from those very shells, served as an apt metaphor for security measures. The question of value, put in central position by the curators, took even more complicated character here as the video essay established yet another link between image and the world. At the beginning of the video Rave emphasized the materiality of image, showing close-ups of highly saturated tropical landscapes and exotic animals, only to confront it with methods of industrial-scale underwater mining. The way that Rave treats the notion of value and analogies between tribalism and late capitalism reminded me of Nicolas Mangan’s show “Limits to Growth”, displayed last year at Kunst Werke in Berlin, comparing large Micronesian Rai currency, carved from stone, to Bitcoin. Since Transmediale’s public and organizers seemed to be sick and tired of the global cryptocurrency hype, a topic generally avoided in most of panel discussions and artworks, apart from one panel dedicated to a book on artists rethinking the use of blockchain technology.

However, finance and capital in general were of course at the center of attention. They were also present in two works worth comparing – Femke Herregraven’s “Sprawling Swamps” and “Offshore Investigation Vehicle” by the Demystification Committee. The first of those two mentioned projects in many ways similar to Rave’s film, however, alert in a wider set of media, combining video, objects and interactive 3D simulation. The Dutch artist and designer explored the world of global finance and material and ecological entanglements of that system providing a metaphor of swamp – an unclear and destabilized territory on which the financial infrastructure not only exist, but also benefits from, as it slips through the fingers of multinational state governance. Although the work must have had some aim of making the conditions it referred to more clear, I worry that it obfuscates them in too much of speculative and imaginary fictions. Not to mention the 3D digital environment, controlled with a touchpad – lagging and unclear interface made you click randomly and see what would happen. The interface was painfully real, but I don’t suppose this was the aim of the artist.

By contrast the “Offshore Investigation Vehicle” was even more rich in elements and objects composing the installation. UK-based duo Oliver Smith and Franchesco Tachini conducted the exhibited project during a special Transmediale Residency last year. To optimize taxation and maximize profits, they decided to establish a real offshore company the main effect of which was to track their activity into an informative guide to avoiding taxes. With activist feeling and a clear aim to expose tax evasion – the notion that if ordinary people went offshore, the governments would be forced to regulate it more strictly and seriously. It was funny looking at bright yellow trunks designed by the artists, but got really serious in the accompanying publication that described in detail the whole structure involved in transferring income to overseas fiscal havens.

Talking about sea, an interesting proposition was made by Mumbai–based CAMP Studio in their work “Country of the Sea,” one of the few non-western-centric pieces at Transmediale. Unfortunately, their idea of inverting the relations between land and water represented by the huge cyanotype print of common waters between the Red Sea, Aden Gulf, Persian Gulf and Arabic Sea, were lost between other parts of the work. It was however intriguing from the perspective of alternative cartography, connecting intersectional threads from post-colonialism, alternative economies and local versus global hierarchies in international trade.

There were more works though that considered post-colonialism and globalization as central but from totally different perspectives. First of them might still have been problematic for some but maybe not for the Transmediale audience. It could be simply called activism or research, but the use of visual tools, ways of presenting, performative practices and – above all – interdisciplinary team make such strict divisions obsolete. The Forensic Oceanography (a branch of Forensic Architecture group based at Goldsmith, University of London) presented two investigations into migrant death as information visualization.

A piece of furniture placed in the middle of a small room looked like taken from some kind of business private jet, adorning Transmediale with the promise of borderless travels. But running away from politics, conflicts and disasters is just a delusion, not only here at Transmediale, but in general.

Yet another way of presenting issues of post-colonialism and race (in this case reinforced with the question of class was that of a UK duo Larry Achiampong and David Blandy in a video trilogy entitled “Finding Fanon.” Friends from London who grew up together in the 1970s and 80s, Achiampong was born the son of paperless African immigrants, while Blandy was born to a middle-class family with a colonial background, whose personal relations are weaved together in the film. The source figure for the trilogy, Frantz Fanon, was a famous psychiatrist, philosopher and writer, born in then French colony of Martinique in 1925. Based on his education, but also his personal experience of being black in a world bespoke with colonialism, Fanon implemented psychoanalysis and dialectics to describe conditions of the colonized and ways towards their liberation. Metaphorically searching for Fanon, Achiampong and Blandy are chasing utopian dreams, not fulfilled to this day. Interestingly, they decided to move action of one of their videos to the environment of a GTA series game notorious for violence, discrimination, prejudices and general lack of political correctness. The tension made the story more intriguing and placed it aesthetically in the contemporary post-digital condition, while the remaining two parts were stylized with a retro-futuristic details and post-apocalyptical look, generally sentimental. The exaggerated metaphor of children of different color having hope for the future (guided by the two main characters, played by the artists themselves), seemed to present a longing for Fanon’s return.

A piece of furniture placed in the middle of a small room looked like taken from some kind of business private jet, adorning Transmediale with the promise of borderless travels. But running away from politics, conflicts and disasters is just a delusion, not only here at Transmediale, but in general. Watching video displayed opposite the Vitra-designed sofa, you could see the whole globe simulated in miniature parks, presenting world landmarks in one place. However, the newsfeed at the bottom of the screen would painfully bring you back to the reality of world politics. The piece of furniture used by Yuri Pattison in his installation “Citizens of Nowhere” is a part of Vitra ongoing project (started in 1993) called “Citizen Office.” Does the globalized work force do not need another citizenship? What is the aim of such a concept? I will spare you the corporate newspeak and leave only one suggestion: the sofa is too small to sleep on it.

The problem with writing about artworks at Transmediale is that they are largely based on research, context and conditions in which they were developed, that talking about them in terms of aesthetics and form is not only insufficient, but simply impossible. That is why artists or groups involved in the exhibition were supposed to conduct a special presentation of their piece, and in most cases also take part in further panel discussions.

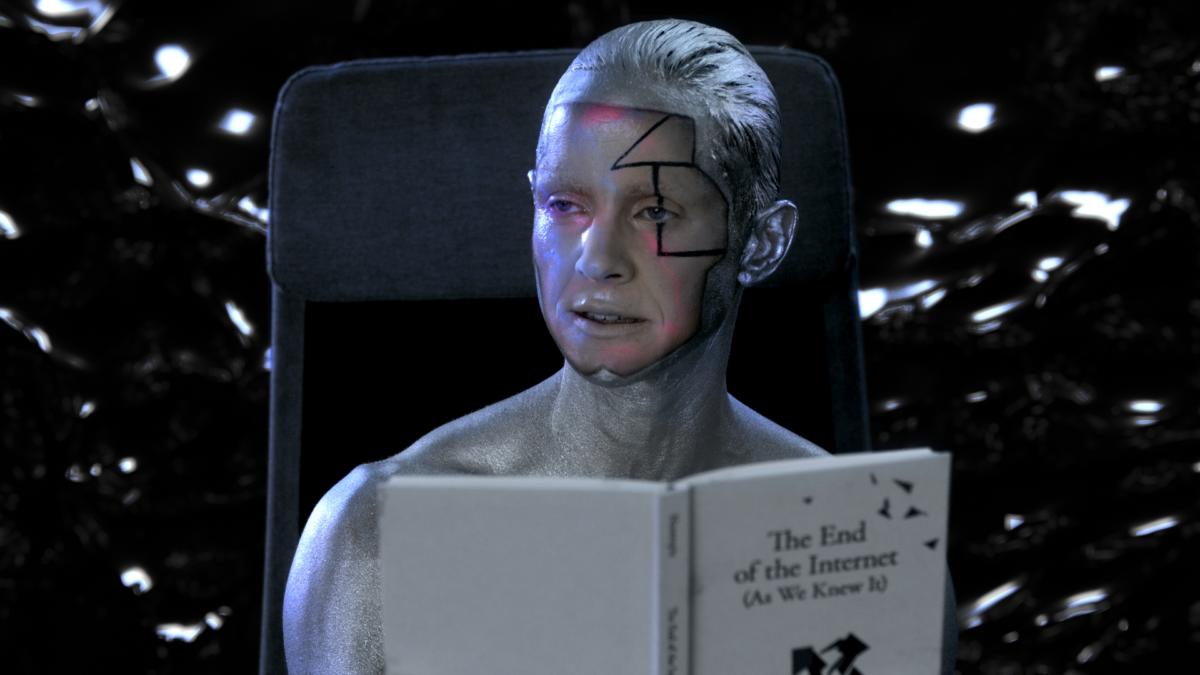

Those eager for some explicitly optimistic and affirmative vision had just one another shot – the main evening event of the Transmediale weekend. Something between a video and sound projection, performance, opera? James Ferraro’s “Plague,” a piece that left me so confused it felt bewildering. Rating by the volume of applause, however, that it was not the best way of spending the Friday night for the majority of the audience in the auditorium of Haus der Kulturen den Welt. Was it boring? At the beginning yes, recurring again and again the same sequence of video and sound during smoothing I could call a prolog. The visualized network, that was probably the title plague, gaining independence, was (as usually) presented as some neurons-gone-mad. As Alexander R. Galloway mentioned in his book „The Interface Effect”, those far-fetched default metaphors of internet as brain will lead us nowhere. Was the „Plague” kitsch? As hell, especially when in the first act a Steve Jobs look-alike entered the scene bathed with sinister red light, crawling like a dog , sometimes getting up to say a few words. Was he Dr. Faust or Mefisto? Don’t know it either, but I’m sure that a choir of bold-shaved people (to be clear, not really shaved) from the second act sold their souls to someone, or rather something, since they couldn’t release themselves from VR head sets. Fighting for freedom from an overwhelming network with their „oooo’s” and „aaaa’s” and „uuuu’s” their of course failed. The end.

Although this description might not read favourable, I must admit a had a pervert pleasure of watching the James Ferraro show. Try not to treat all this as biblical, romanticist, new-age, ponderous symbols too serious, and it will be okay. Or maybe just better. But if it was too late, there was still the last hope: Jonas Lund’s arcade game “The Internet. Express,” hidden somewhere near the festival cafe. Racing in Mario Kart-style with icons of the biggest tech companies instead of cars is fun no matter what. Having lost (it was impossible to win) I decided it was time for me to leave. And yes, I listened to one of James Ferraro albums all the way home.

Imprint

| Artist | Demystification Committee, Yuri Pattison, CAMP, Femke Herregraven, Zach Blas, Lisa Rave, Forensic Oceanography (Lorenzo Pezzani & Charles Heller), Larry Achiampong & David Blandy |

| Exhibition | transmediale festival: face value |

| Place / venue | HKW – Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin |

| Dates | 31 January – 4 February 2018 |

| Curated by | Inga Seidler |

| Website | transmediale.de |

| Index | Alex Foti CAMP Studio Demystification Committee Femke Herregraven Goo Goo Muck Analytics Heather Dewey-Hagborg James Ferraro Jilian C. York Jonas Lund Larry Achiampong and David Blandy Lisa Rave Marc Garrett Marie Luise-Angerer Nick Thurston The Forensic Oceanography transmediale Yuri Pattison |