This is the tenth edition of the festival that you started to create together in 2009. You have divided the festival into two parts for this special occasion.

Solvita Krese: Yes, after several years of discussions finally we are moving the festival to spring. In September there are at least four other festivals taking place in Riga, and we are competing with them for the same audience. In turn, there is less going on in the spring. Usually, however, the Survival Kit takes place in September, so we decided to prepare a smaller exhibition now, and the larger one is planned for the spring. Many of the artists we invited to take part in this edition will continue to work on the other part of the festival, thus they could use this time also as a research visit for a bigger production. Some of the artists have shown existing works or adaptations of existing works this time and will be producing something entirely new for the spring edition.

That’s not all, as far as I know, you are also planning to change the format of the festival into the biennial one.

SK: The biennial format is one of the most widespread forms for reoccurring festivals. Since it’s the most realistic time to prepare a large scale event, research and production-wise as well as financially successful, taking into account the fundraising time. The annual mode puts a lot of pressure on the curatorial, management teams, as well as on the artists themselves if they are supposed to do research and produce new works.

An interesting decision in a situation when just a few months ago in Riga opened other biennale – I mean RIBOCA, which by the way is quite impressive.

Inga Lāce: The more events dedicated to contemporary art there are, the better it is for the city, for both local and international audiences. Especially if we are thinking in general about encouraging a wider audience that is interested in contemporary art and the critical thinking that it enhances. An event like RIBOCA, with a massive international PR, has created a critical mass of international attention focusing on the art scene in Riga, which consequently brings the audience to other art events in the city, which are taking place simultaneously. However, Survival Kit and RIBOCA have very different scales and formats, which was especially visible this year when they overlapped. We could hear feedback from people who liked both of them or liked and completely disliked the other. But still, there was this possibility of choosing and possibility to compare. Also, RIBOCA is a new initiative, which we still need to see develop in order to create its identity, however, Survival Kit has its history and has grown from the local scene, as well as it has a strong ideological position. Having mentioned all the pluses of another art event in the city, I am also wondering why exactly one should decide on a biennale, an art event for example, instead of creating a strong art institution collaborating with the local art scene on a daily basis, which would perhaps fill in the gap of the still non-existing contemporary art museum.

SK: The artistic scene in Latvia is very vivid but at the same time its condition is very precarious. In the field of contemporary art NGOs are mainly active here, but there are no institutions subsidized by the state or the city which are responsible for the development of the sector.

And what about the local national museum? There is a possibility to see contemporary art there.

IL: Yes, they have a contemporary art programme. Moreover, often we collaborate and prepare contemporary art exhibitions at the museum. Then we also carry out research work for exhibitions, as well as do fundraising.

The artistic scene in Latvia is very vivid but at the same time its condition is very precarious.

The motto of this year’s Survival Kit festival is “Outlands” – what does it mean to you?

IL: Outlands is a term we use instead of margins or periphery which seem to have already exhausted their meaning and also associated too much with the negative characteristics. Outlands instead – as a term and also space to still inhabit – includes both elements – the geopolitical marginalization, but also the potentiality that comes with it.

This year we collaborate with two co-curators – Sumesh Sharma from Bombay and Catalan curator Angels Miralda, which were our interlocutors in a discussion about Riga, that we initiated. If we try to look at it from another perspective, we can see Riga as one of the so-called outlands, belonging to the as-yet-little-studied Eastern Europe, charged with powerful potential, where Riga, Prague and Sofia form a self-sufficient seismic zone of creative eruptions. This does not mean that Riga is the new Berlin, but rather that, if we step out of a Eurocentrically limited perspective, it is possible to suggest that Bombay is more important than Paris on the contemporary cultural map of the world, or even to admit that conventional measurements of importance – size, popularity and so on – are in themselves useless. And also that the Western metropolises like London and Paris should not be the decisive points of reference, which set measures by which one can classify the other cities.

For example, as peripheral the Latvian scene may be, life here seems easier from many other perspectives than, for example, in London, where the conditions of production for artists are much harsher.

An important context for us is also the refugee crisis and the way minorities function in Latvia. For example, in Latvia, we have a large Russian community, and many processes, also division between the two communities, is a manifestation of a failed integration policy.

What is the attitude of Latvians towards refugees?

IL: When we had to accept refugees from the division established by the European Union, we agreed to accept seven hundred people. However apart from a real problem of refugees there emerged another one, because there were simply too few of them if one compares to other EU countries. Unfortunately, there is xenophobia and racism present in Latvia, too. And if the political class is not showing an example, it’s very hard to convince part of society that one should work out a new level of tolerance.

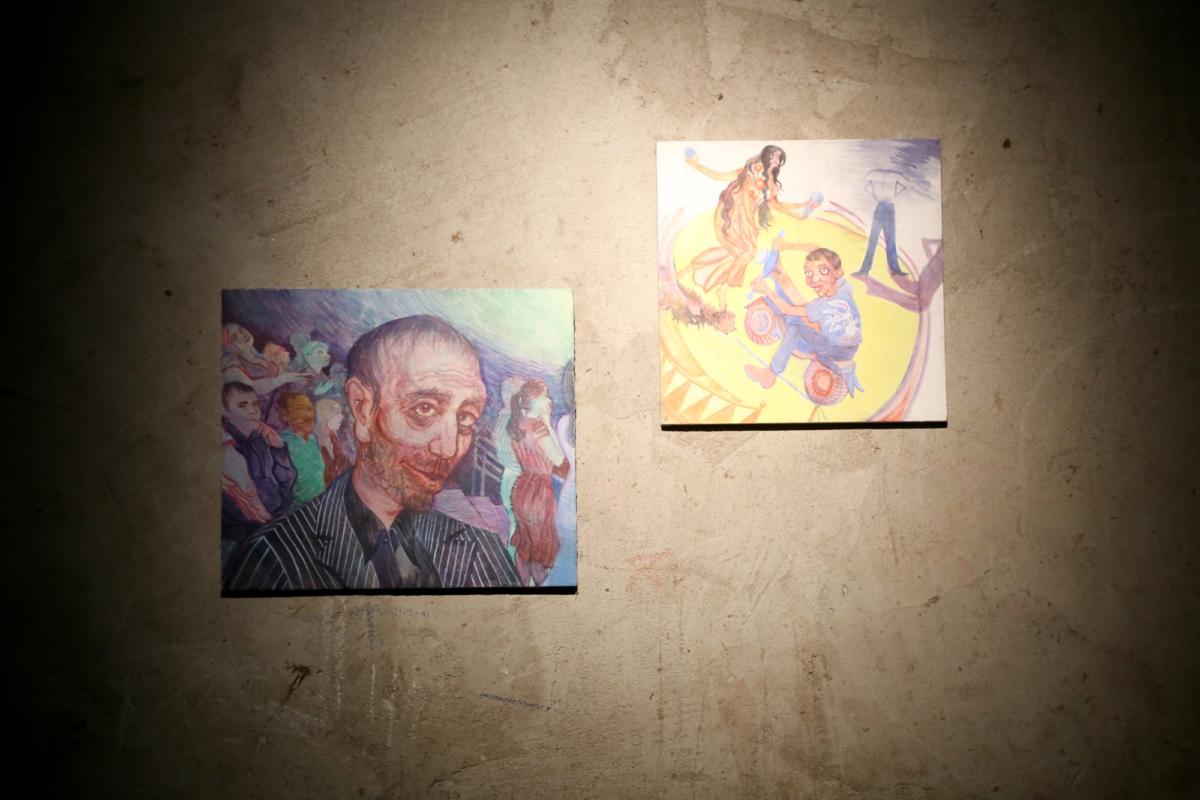

Each edition of the Survival Kit takes place in a different place. This time it is a circus. How does the context of the place relates to the main theme?

SK: Rigas Cirks is a special place, the building of this circus is 130 years old and is one of the oldest objects of this type in Europe. What interests us in the idea of a circus is the state of being on the go. Circus performers are always on their way, somewhere in between, they are migrating from one place to another. A separate issue was that while working in this building we had to deal with the treatment of animals. Since animals lived in this circus, in some rooms you can still smell them, like in a room where lions were kept. Now, however, circuses have been undergoing modernization and preparing repertoire without animals.

If we step out of a Eurocentrically limited perspective, it is possible to suggest that Bombay is more important than Paris on the contemporary cultural map of the world, or even to admit that conventional measurements of importance – size, popularity and so on – are in themselves useless.

What will the spring edition of the Survival Kit look like? Where are you planning to locate it?

SK: We plan to move to the other side of the river, to a district located outside the centre and which is living its own, separate rhythm. In a certain sense, it is still outland for many inhabitants of Riga for whom it is sometimes so difficult to cross the river considered as a border in their mental map of the core of the city.

IL: The other side of the river is a bit more residential, however, it does already have several very lively places of culture. And some new processes are planned to take place there next year. So, it has a potential to become an important place on the cultural map of Riga.

Survival Kit is 10 years old. Can you remind us of the beginnings of the festival? What are your general reflections after this time?

SK: The first edition of the festival was a response to the economic crisis that erupted in Latvia ten years ago. Many shops and companies then went bankrupt and there were plenty of vacant lots in the city. We decided to take advantage of this situation and do something in these empty spaces to somehow enliven the art scene here. It was a depressing moment, the budget for culture was cut by 60%. I remember that during the first edition of the festival one of the projects was a bar in which the artists cooked soup. This bar has become a meeting place for the local artistic community and space for exchanging views about the crisis and potential ways to get out of it.

At the beginning the Survival Kit used to have a more experimental formula, it was more based on DIY strategies. Now it is becoming more and more professional. People often ask me whether it makes sense to continue organizing the festival, but on the horizon, there are always new problems and the question “how to survive” is still valid. Survival Kit is also still the biggest event organized by the local artistic community and by other initiatives, which emerged from it. Thanks to them, the city is alive, so Survival Kit should continue.

Imprint

| Artist | Kader Attia, Nasreddine Bennacer and Krishna Reddy, Cassius Fadlabi, Cibelle Cavalli Bastos, Roman Korovin, Kris Lemsalu, Katrina Neiburga, Orbita, Judy Blum Reddy, Janek Simon, Zīle Ziemele, Anastasia Sosunova, Slavs and Tatars, Agnieszka Polska |

| Exhibition | Survival Kit 10.0 |

| Place / venue | Riga Circus |

| Dates | 6-30 September 2018 |

| Curated by | Solvita Krese, Inga Lāce, Sumesh Sharma, Àngels Miralda |

| Website | lcca.lv/en/survival-kit-10 |

| Index | Agnieszka Polska Anastasia Sosunova Àngels Miralda Cassius Fadlabi Cibelle Cavalli Bastos Inga Lāce Janek Simon Judy Blum Reddy Kader Attia Karolina Plinta Katrīna Neiburga Kris Lemsalu Nasreddine Bennacer and Krishna Reddy Orbita Roman Korovin Slavs and Tatars Solvita Krese Sumesh Sharma Survival Kit Zīle Ziemele |