IPoP – Institute for Spatial Policies

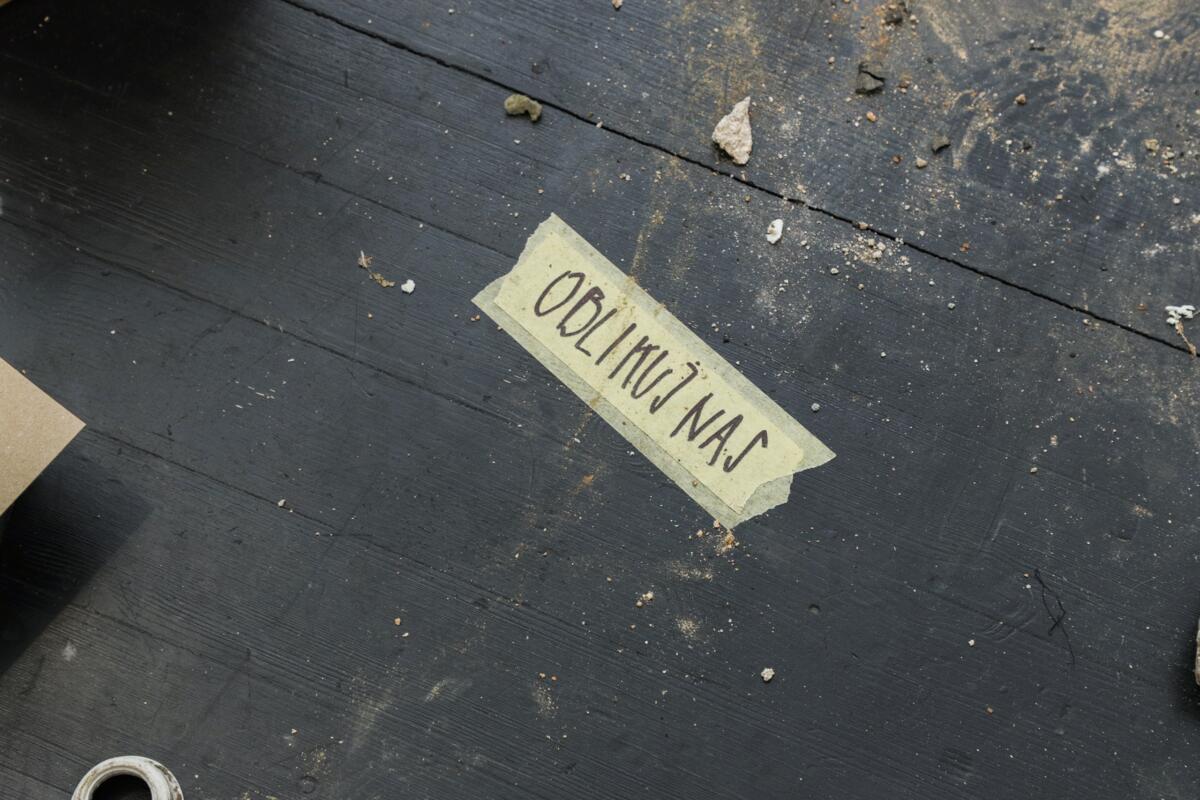

For more innovation and diversity

-

Independent production spaces

When we talk about independent production spaces, we are usually talking about community spaces. This means that they are developed based on the needs of the community of (potential) users. The bond that connects the members of the community is first and foremost the profession they do, but that is usually not the only bond between the users. As community production spaces are more likely to be found in creative, cultural and artistic professions, where the boundaries between work and leisure are blurred, users are to some extent also connected by their lifestyle and mutual trust.

Independent production spaces are more or less independent of institutional support, which does not mean that they never receive support from institutions, but that this support, when it does occur, is project-related and thus unpredictable. This enables these production spaces to work independently.

- Their development

It is quite common for such spaces to develop out of a community, which in practice often means that development depends on a few interconnected individuals, who nevertheless enjoy a great deal of support in the community of potential users. The start-up of such spaces usually depends on the investment of volunteer work and other resources (tangible: e.g. furniture and equipment, intangible: e.g. organisation, coordination, communication) by the user community.

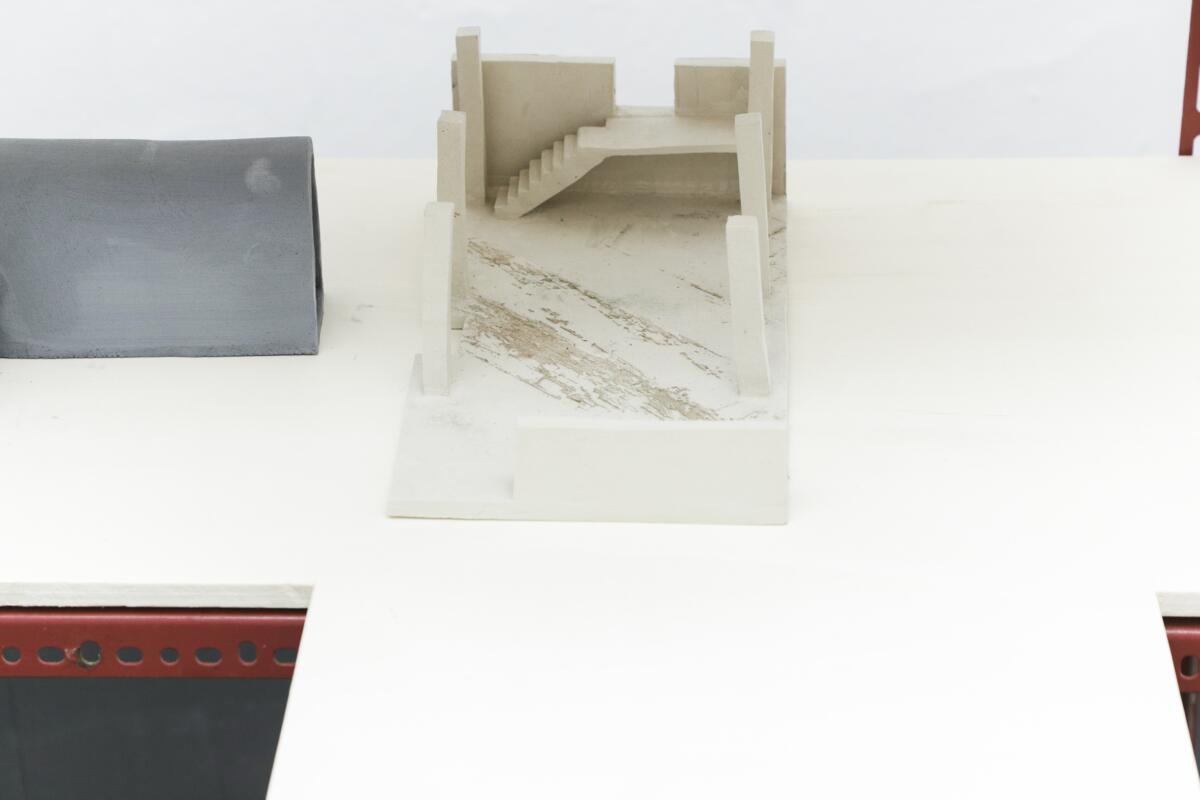

Independent production spaces are easier to develop in cheaper buildings that allow experimentation. Firstly, because these spaces are cheaper, and secondly, because these spaces allow for adaptation and experimentation, unlike expensive new buildings.[1]

It is not uncommon for these spaces to be old industrial areas or buildings. Older industrial buildings are often located near the city centre and at the same time have large production halls. An example of such areas in Ljubljana are the Tobačna factory and Rog. In both areas, there was a large concentration of production spaces at certain times, where creative or cultural activities also took place or even stood out.

- Why we need them

The provision of accessible production spaces is the most obvious service that independent production spaces provide, if that term can be used at all. However, their function is broader.

These spaces are often used by people working in the creative industries, i.e. professions that individuals often do themselves. Collaborative production spaces enable networking and potential collaboration as well as mutual learning. At the same time, these spaces are one of the few points where workers in a similar profession also meet in person. As these are often professions with the characteristics of precarious employment and project collaboration, a shared production space is one of the few constants within a particular activity and profession or professions. An essential component of these spaces is to enable collaboration and mutual exchange of skills, experience and knowledge. This is the added value of such spaces and therefore worth supporting.

However, not all users of the community space necessarily seek or want to participate. It is possible that participation in the community is only to facilitate individuals’ access to a production space because it is a way to share costs or reduce certain common costs. In such cases, the main motive of the individual user may be the production space rather than participation in the community, which is of course a perfectly legitimate approach.

- Urban policies

About fifteen years ago, the concept of the creative city came onto the agenda of cities, and this was the beginning of more strategic support for the cultural and creative industries, as it was believed that these two sectors represented the untapped potential for new jobs and economic development. As the usual way of supporting entrepreneurial development had often proved unsuccessful – cultural and creative activities are only slightly different from usual entrepreneurship – cities began to create new forms of support. Two approaches stand out in particular.

The first is the construction of large new spaces for the presentation of culture, with Bilbao often cited as a model. The second approach was based on the idea that to develop the creative professions we do not need new so-called flagships with large, expensive spaces, but affordable spaces in old buildings that allow the production and development of new ideas.[2] While the first approach was financially demanding, the complexity of the second was hidden in the organisational approach. Independent production spaces, especially collaborative spaces, develop from the bottom up or not at all, so the city administration can only support them but not develop them itself. Cities that opted for the strategic development of the cultural or creative sector pursued the development of such spaces with inclination, while indirectly supporting the development of production spaces. Either through tenders by which such spaces received funding for various programmes or through co-financing or free renting of suitable spaces. At the same time, cities kept sufficient older spaces suitable for the formation of community production spaces through urban policies and planning documents.

- The balance between expensive representative and accessible production spaces

If we spare ourselves the decision of whether it makes more sense to build or renovate expensive and luxurious large spaces for the presentation of art and culture on the one hand, or to allow the creation of affordable, sometimes neglected or older production spaces on the other, we come to the conclusion that they are two parallel, even complementary processes. Two sides of the same coin, you might say. However, the sides of the same coin are identical on the surface, which is not insignificant, as there must be a certain balance between the two approaches described above. Otherwise, if too much emphasis is placed on large and luxurious presentation spaces, over time this can hinder the development of content that could fill brilliant new buildings, as young artists cannot flourish if there are not enough production spaces. This is especially true for young artists from less affluent social backgrounds, who do not have the financial background to support artistic development. Thus, art and culture may become impoverished in the future if it becomes the domain of the middle and upper classes. However, we by no means want to make the inaccessibility of production spaces the main obstacle to the development of underprivileged artists – these obstacles are of course greater and go beyond the realm of production spaces as they are broader socio-economic issues.

- Independent production in Ljubljana

Ljubljana is a small city in terms of population. Nevertheless, Ljubljana is characterised by a developed cultural and creative scene, which cannot be taken for granted, as Ljubljana has a relatively low critical mass compared to other European capitals, for example. Due to the low critical mass, the spaces where new trends develop, i.e. independent production spaces, need to be actively supported, as their survival on the market is more difficult due to the already mentioned small size of the city and critical mass.

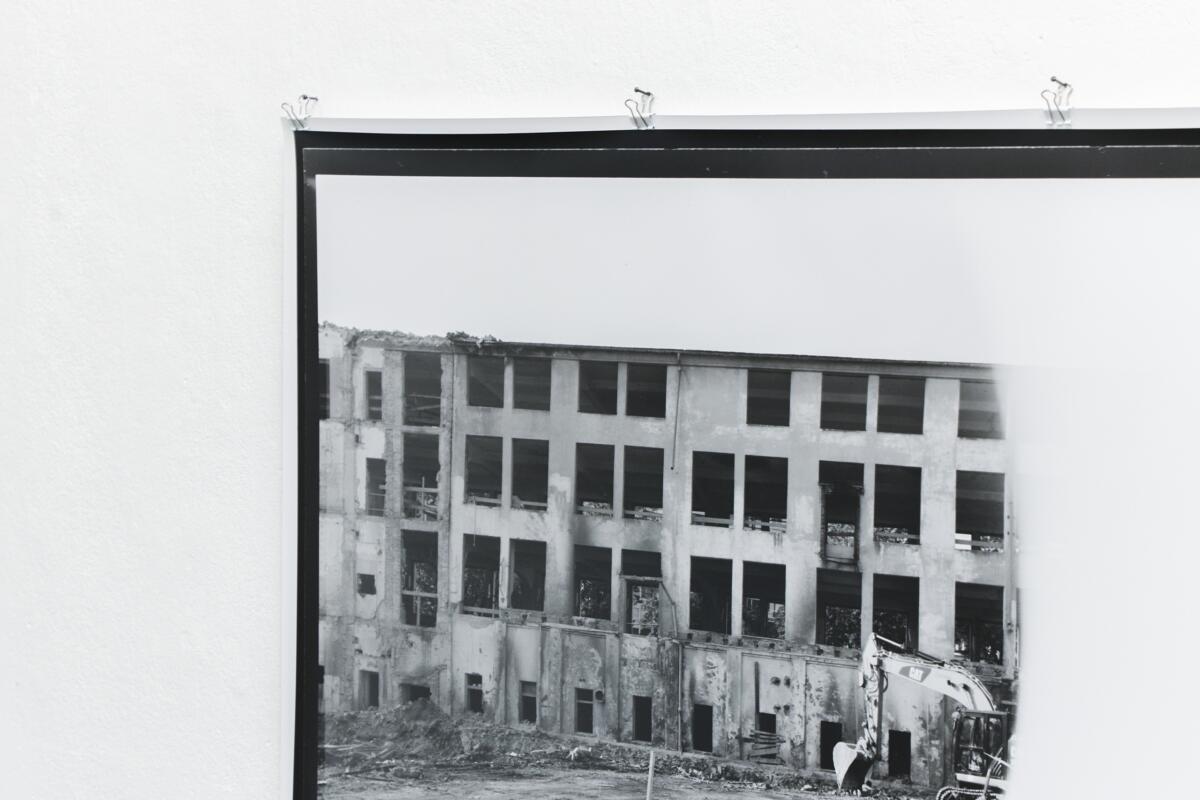

In recent years there have been two obvious processes in Ljubljana. The first is the slow closure of various independent production spaces. In recent years, Kreativna cona Šiška, Poligon and many other production spaces in the Tobačna factory have been closed, and recently the Rog factory was also demolished, which, despite all its problems and challenges, offered a huge production space to various individuals and collectives.

At the same time, the number of more or less dazzling spaces dedicated to the presentation or consumption of culture and art, so to speak, has been growing for more than a decade. Kino Dvor, Kino Šiška, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, Tobačna 001, etc., while the extensive renovation of Cukrarna was recently completed, as well as the extensive renovation of the Rog Centre, which is supposed to be a place for creative production. The question is for whom and what. The broader question, however, is whether the balance is not tipping too much towards presentation spaces, while at the same time widening the gap at the level of production spaces?

- The time for independent spaces

In one of the first lessons on the basics of economics, the transformation curve is explained, which, greatly simplified, says that the more cannons we have, the less butter we have, and vice versa. If we already have many cannons, each additional cannon is less useful, while new units of butter would be very useful, since we have few of them.

If we transfer the curve to Ljubljana, we see that the independent production space is shrinking, while the number of institutions for the presentation of art and culture is increasing, and at the same time, we are investing significant public funds in them. At the same time, these investments have intended or unintended effects on the environment – which is improved and thus made more expensive by the considerable public investment. Since access to spaces is based on a free-market, neoliberal logic, large public investments affect supply by increasing the price of spaces, which further limits access to such spaces for people with fewer resources. So, the question is whether these investments really benefit those who need production spaces. Often these are young artists who have not yet made it into the elite. We should therefore not be surprised if art develops differently as a result – there will be less diversity and innovation because there will be no production spaces where the most innovative part of art and culture can develop in cooperation, perhaps even in community. And that is ultimately a pity for the diversity of the programme of institutions that present art and culture.

Tomaž Furlan

FIND YOUR FEET or How Something Happens Out of Nothing Which Is Not Nothing!

The workspace, the studio, should be an integral part of the production process, but that is not really the case today. Digitisation has saved a lot of the resources needed for work. You might think that sooner or later it will occur to someone that they no longer need to leave the house to work. This is what we practised as students and also later. The ability to turn a corner of a room into a veritable workshop is often one of the key talents of a young artist. But still.

We are not all the same generation. Let us put it this way: in the days of my professional youth, the concept of the artist was not so cursed. Come to think of it, we were no longer treated as something special either. The poetic bohemianism and the social consensus that the artist’s behaviour was allowed to be a little more flexible were definitely in place. The glorification of talent and skill was no longer necessary. The world seemed to accept our existence. That was a right at the time. The right of the artist.

Study and all the benefits of the institution were followed by professional adolescence.

I will tell my story.

At its best, the institution gave me the opportunity to descend into the morass of professional machinery, ups and downs, an unfair world and independent survival. Some of us made the stubborn decision. We soon realised that there was no “modus operandi” for a successful career in the arts. But that does not mean I will not invent it, I often thought. Naively, this search for the ability to create something nevertheless created a kind of offshoot of the system over time.

Opportunities!

One of the most important tools for the survival of creativity was the current and uncompromising recognition of the opportunities that presented themselves. Had I been smarter and not believed in making it into a big shot artist, I probably would have been more cautious. Cultural colleague Dejan Koban’s motto, “from asshole to star”, is certainly an important part of this microsystem. It is still about the desire to work, let us be clear about that. A simple strategy required the following: a space to work, an idea, materials, tools and of course the most important ingredient – people.

Every opportunity that came my way was a good opportunity and I seized it with both hands. It all started before my studies, when a group of young “artists” managed to get funds from a local student club in a naive but cunning political campaign. For nothing more than designing sets for student theme parties and some creative contributions to student events, we were given a huge space in the abandoned pool of the Transturist hotel in Škofja Loka. A studio in an empty pool! That seems crazy to this day. But it was not that easy. Back then, student clubs had a lot of money, and a few nice artists quickly convinced the then clumsy computer people on the club’s board to scrape off part of the subsidy for sports and trips abroad and leave us “artists” some spare change. Of course, it was not all in good fun. It all went into the work. On the premises of the so-called Atelier CLOBB[3], we carried out all kinds of extroversions in addition to our creative work. Children’s workshops, the aforementioned set designs, workshops for students, etc., soon we also set up a silkscreen, print workshop, a photo darkroom, a ceramic kiln, etc., everything and more, and we did it all ourselves. The team grew quickly. In a little over half a decade, we were almost an institution. Somewhere at this point, my studies at the Academy of Fine Arts ended and I also threw myself into new opportunities.

Even more opportunities!

Sometime towards the end of my studies, another opportunity presented itself. “Game changer,” I said to myself. I was offered a completely dilapidated attic at Metelkova. I rushed in like a bull with everything I had. The room had no doors or windows, no insulation, almost no floor and no installations of any kind. But there was plenty of rubbish left by the homeless and a makeshift toilet in this corner or that. I knew almost no one. Anyway, in the following months, even though I had finished my studies, was heavily in debt and of course had no money, I dragged everything into the studio that could be scrounged or collected in the area. When I had “knocked it all together”, so to speak, I had a studio. Something else I had always known was somehow subconsciously quickly confirmed. You can not do it alone. Colleagues, neighbours and fellow sufferers were the main raw material of my studio. So were art careers. A space like Metelkova Mesto offered everything!

The opportunity presented itself quite by chance. Everything else was not a question of economics, but enthusiasm. Endless hours of investment in spaces that even today cannot be said to belong to anyone. Making contacts, creating connections, joint actions and, of course, being creative. The process really did not have a break, nor did the goal. But we created spaces, friendships, events, careers, opinions and new opportunities.

Most of all, opportunities!

Frogs boiling in the same pot probably sense the collectivity of the situation. I can not say that creating at Metelkova is much different. So far, we have not been cooked all the way through. There was definitely always something to do. The most difficult thing to understand is probably the way such a formation as Metelkova Mesto works. The set of interests that are not coordinated through the construct of rules, control and sanctions means dynamic and communicative action and, above all, a lot of collegiality and patience. In the end, everything can be agreed upon. The main thing is that such a space makes the work possible and that help is always at hand. Experts of all kinds are around every corner. So are drunks and drug addicts. A Mini Mundus of an anthropogenic ecosystem. These were ideal conditions for my production. I created the working conditions myself, the environment is not competitive, and the utopian idea of art without economics is a generally accepted concept. What more could one wish for? Of course, this kind of production potential does not exist for free. It takes a lot of effort and intelligence to sustain such an environment. Collectivity is spontaneously mandatory. It is necessary to survive all kinds of attacks. Physical, ideological and economic dangers lurk around every corner. The worst, however, is certainly the least obvious: the omnipresent need for growth. In another context, one would speak of “economic growth” or “development”. Curbing this probably requires the smartest decisions. How to grow, where to grow, why to grow? Is it really necessary to grow? If I remember correctly, all the momentum came from the need to work. Survival is the duty of everyone involved, and the concept of work is not necessarily measurable only in terms of their economic potential. Why then such an unstoppable drive for expansion, pluralisation and administrative order?

No more opportunities?!

As time goes on, the world of opportunities seems to narrow somehow. It probably simply changes. There is more and more bureaucracy, less and less collective practice. There is more and more funding for technology, less and less space for work. There is more and more “private capital”, less and less infrastructure. There are various reasons for this. Sometimes just the fact that there is less administration and more control in the acquisition of technical equipment than in spatial and infrastructural operations. But this supposed administration and bureaucracy has nothing whatsoever to do with artistic creation. It is an externally imposed construct. The origin of the resources that support creativity is certainly not an important aspect in the creative process. A studio is a studio, whether it is supported by the state, local communities, private funds or disobedience. It is a space where art is created. You could say that one big change has taken place. The collective need to create order has perfected the bureaucratic elements of professional existence to such an extent that today, it seems, heterogeneous and spontaneous creative spaces are only possible on the basis of private means. These should be called “private capital” today, even if this “capital” is often only a means of subsistence and not an accumulated means of business investment. I admit that I myself did not realise how cleverly the capitalist idiom has turned us into consumers. Find your feet, is more rarely a tool of manipulation with matter. It seems to be merely a tool of economics and bureaucracy.

The origin of the resources that create the working conditions for artists is completely irrelevant. When we talk about spaces dedicated to artistic creation, resources such as money and rights are merely a necessary evil. Workshops, studios, stages, etc. do not make an artist. An artist makes an artist. But the artist needs them. The transition into the “professional” stage of life is accompanied by a multitude of consensuses. Enthusiasm largely replaces pragmatism. The fear of failure becomes a constant. At first glance, the reckless investment of modest means and immodest energy in extremely risky situations seems to be a thing of the past. The conformism of mutual calculation becomes the modus operandi of the working strategy. Utopian combative creativity has exhausted itself. This is how I came to private means myself. My art production is driven by my savings and my inheritance.

Ergo!

Finally, I too have become a pebble in the great sandbox. This appears to be carefully ordered and managed, but time and again it turns out that the overriding guiding principle of this self-appointed system is merely the fear of the other and the need for the ultimate order. An order in which everything runs smoothly and nothing needs to be done. An order in which there is no room for deviation and experimentation. If that is not the exact opposite of everything that has driven me in my zeal for work over the past decades.

Trust is the key. Somewhere along the line, it happened that I no longer encounter it anywhere in its original, interpersonal form. The only element of trust that has remained, and at the same time seems to be the only element of the work strategy, is “added value”. This Trojan horse has finally reached even the most obscure working practices, such as art. Settling artists in run-down urban areas means gentrification and real estate profit. Squatting is slowly merging with local added value for tourists. Alternative club life is measured by the taxman. Capitalism has managed to appropriate every movement in artistic activity, no matter how small. Non-commercial practices seem to be a term from the past.

I like to observe the practices of younger colleagues, and it is not hard to see the modus operandi of “find your feet”. Either you are a tiger ready to pounce on calls for submissions and can exploit public loose change for a short while, or you are “networked” and on the lead for a cheap garage with your friends. Submission tigers (all of us) are gentle animals. Many rules and tasks have to be taken on board, so there is not much energy left to create. And this creation is as filtered and coordinated as possible, even before these “opportunities” occur. But there is nothing in a friend’s garage (or grandma’s basement). No tools, no equipment, no professionals. Often there is even no heating.

Temporary use of abandoned spaces, autonomous collective production spaces, non-governmental organisations supporting artistic creation, public technical workshops, public depots, open truly non-profit dates on stages, basements in institutions …

All these practices persist, of course. Preferably somewhere away from the public eye and criticism, otherwise they seem to commercialise themselves for their own safety. As an eternal idealist, I find it hard to understand why.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1] Numerous authors have written about this, for example Jane Jacobs, Richard Florida, Richard Lloyd, etc.

[2] At this point we could also delve into independent exhibition, theatre or performance spaces, as they have similar functions in parts, but we will limit ourselves to production spaces.

[3] CLOBB stands for “computer land overtaken by body” and goes back to a poster with this slogan that I had made and hung on the wall of the Red Oyster Youth Cultural Centre on the evening that we received the funding approval at the club meeting.

Imprint

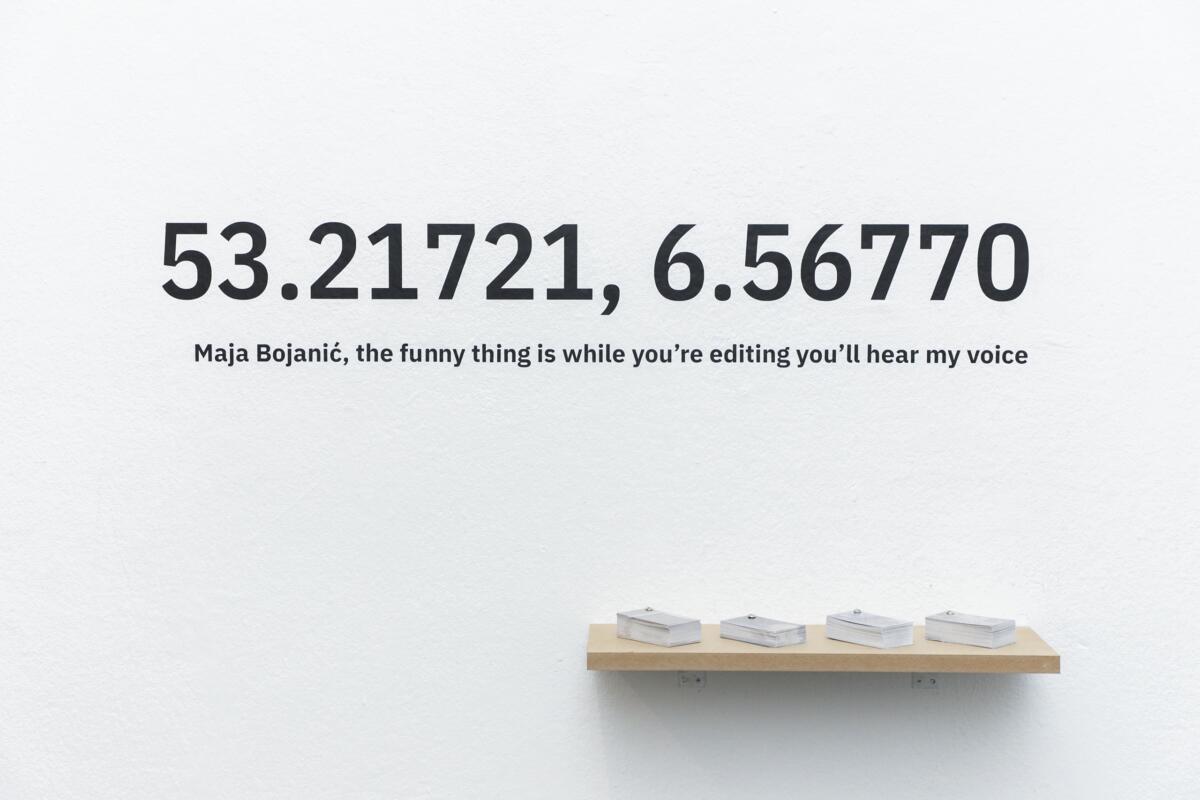

| Author | Tia Čiček, Peter Rauch, Sara Rman, Anja Seničar, Tomaž Furlan, IPoP – Inštitut za politike prostora, Maximilian Lehner |

| Artist | Peter Fettich, Lin Gerkman, Hanna Juta Kozar, Urška Preis, Luka Prijatelj, Peter Rauch, Sara Rman, Anja Seničar |

| Title | skup | photo book |

| Exhibition | SKUP |

| Place / venue | Škuc Gallery |

| Dates | 11 November - 9 December 2021 |

| Curated by | Tia Čiček |

| Photos | Marijo Zupanov © Škuc Gallery |

| Publisher | Zavod Artard, Galerija Škuc |

| Published | November 2021, Ljubljana |

| Website | www.galerijaskuc.si/publication/skup-photo-book/ |

| Index | Anja Seničar Galerija Škuc Hanna Juta Kozar IPoP – Inštitut za politike prostora Lin Gerkman Luka Prijatelj Maximilian Lehner Peter Fettich Peter Rauch Sara Rman Škuc Gallery Tia Čiček Tomaž Furlan Urška Preis |