Joanna Sokołowska: We are meeting five years after your graduation from the Dutch Art Institute. Can we start our conversation with your formal and nonformal education as an artist?

Ulufer Çelİk: Sure. First I was trained as an architect at Istanbul Bilgi University, and then I did my MA at the Dutch Art Institute, which mainly focuses on artistic research and development. I only had a studio after the completion of my studies to focus on my artistic practice. Formal education as an intellectual training is very supportive, but it could also be a trap of western academia. Non-formal education and its ways of making helped me see outside of this bubble, and break free from it in my practice.

How did you deal with it?

I felt that this kind of knowledge was like chains that were haunting me. Having European white male dominated reading lists made me feel like I need to fit into their vocabulary, that my work doesn’t belong to. I wanted to make rather joyful art but didn’t have the tools and words to describe and stand on. The breakthrough came during a master class mentored by Hypatia Vourloumis. We were dealing with collectivity and a lot of unorthodox ways of making. And I started listening to myself, to who I am, where I am from, how Anatolian women feel and see. So I refused forced texts and resources and chose those rooted in oral, peripheral, and ancestral knowledge. Subsequently, I started to feel and see more from my body, which gave me power. I realised the manipulated parts of my world view, that made me lose confidence, have hidden my own story from me. So, I started to relate myself with experience and wisdom, and not towards the words of patriarchy.

So you needed first to learn, and then to unlearn to find your own language. On the other hand you received a top-level education in one of the most globally outstanding schools of art, which also gave you the tools to contest it. What are the sources contributing to your artistic identity today?

Myths, making myths, collaboration, relations.

Tell me about myths.

For me, mythmaking is about exploring time in a non-linear, spiral form. It’s a realm in which the past, present, and future are always informing each other. It’s an experience of cyclicality and exploration of what that particular time has to offer. I say I make myths, which means, for me, I work with a subject, or I have something in mind that maybe happened back in the day in my family, or someone told me about a memory, or maybe I come to a new place and then I start collecting information about the past, present, and future. I try to bring them all together somehow in this body and explore their relations. And this, for me, is a myth. It can be a memory, an incident, an opening moment in time. Then I try to make sense of these fragments.

Would you agree that you actually refused to follow a topical myth of contemporary art of Western origins, which is criticality? I mean, the idea that art is supposed to be critical about myths, to deconstruct them to disenchant the world of illusionary ideologies. Can you elaborate, drawing on the concrete example of your concept of “radical mythocracy”?

I think that mythmaking has a potential to be critical, too. The idea of “radical mythocracy” evolved from my family history. My grandfather shared a dream of a Greek goddess revealing a hidden treasure in a mountain, when he was seven. He convinced his parents to search for it and started digging the hill until they hit a very hard stone and couldn’t continue to dig. Maybe it was a subconscious process. Years later, archaeologists from Boston excavated the area, discovering the lot of coins and treasures in this hill, which was apparently an ancient bank. I visited the Peabody Museum of Archaeology at Harvard University and found stolen items from the village in the collection. They were among objects from archeological sites all around the world, like Turkey, Mexico, and other places that were subject to colonisation, or in other unequal relationships with the West. It was possible to steal these cultural objects because of the disparity of power and money.

What was your reaction seeing your stolen cultural heritage in the American museum?

When I found a box from my village I realized the object was broken. So I started making collages using motifs of the broken pieces. I wanted to make a new myth that talks about the present with artefacts from the past. This myth is directed towards the future, so as to reverse colonialism and its trajectories, to make people realise that looted objects in American or European museums should be returned to the places where they come from.

So you create new narratives drawing on fragments from the past…

Exactly. Fragments are so interesting because they are not the outcome. From little pieces you can create your own reality with so many options. When you put different fragments together, the new montage reveals new insights. From flexible units to porous systems. They never reveal a black and white structure. You can create non-dualistic forms. You are never forced into one ultimate result. There are always multiple choices. In ‘Towards a Radical Mythocracy’ there are more than 60 arrangements of pieces that were captured in that moment. The nature of the work challenges me in the exhibition processes too, and work is benefitting from this.

Digging in the past you create new constellations of fragmented narratives that were never before composed together to modify current thinking about the past and open up new ways for the future.

Yes, exactly.

Why do you find it so important to communicate through mythology?

I think it has the potential of a learned lesson, which doesn’t belong to one generation. It is an intergenerational, collective lesson that can direct us in our path to be better humans. Because we can find wisdom from the past in myths, which is still alive, and we can relate to it. Myths can also support us in times of crisis. Take the recent (February 2023) earthquake in Turkey. You don’t know how to talk about it. You don’t even know how to feel it. What to do. Especially when you’re away as an immigrant in the Netherlands. At that moment, with my friend Merve Kılıçer, we felt that we wanted to engage in this and decided to create a performance centred around the earthquake. As we performed in a room full of people, we felt a collective connection in the way people processed their emotions. This shared experience served as a kind of forum for collective processing, acknowledging that these events are inherently collective in nature.

This brings up another closely related question about collective dreaming, archetypes, and the collective subconscious. It seems like these are recurring motifs in your work. Can you share more about this?

Joseph Campbell aptly describes myths as public dreams and dreams as private myths. To engage with collective myths, one must traverse individual experiences, often gifted through dreams. The interplay between personal and collective realms, exemplified by my grandfather’s memory and its connection to a dream, consistently draws me back to exploring dreams. Despite my limited personal engagement with dreams, this dynamic inspires my artistic exploration.

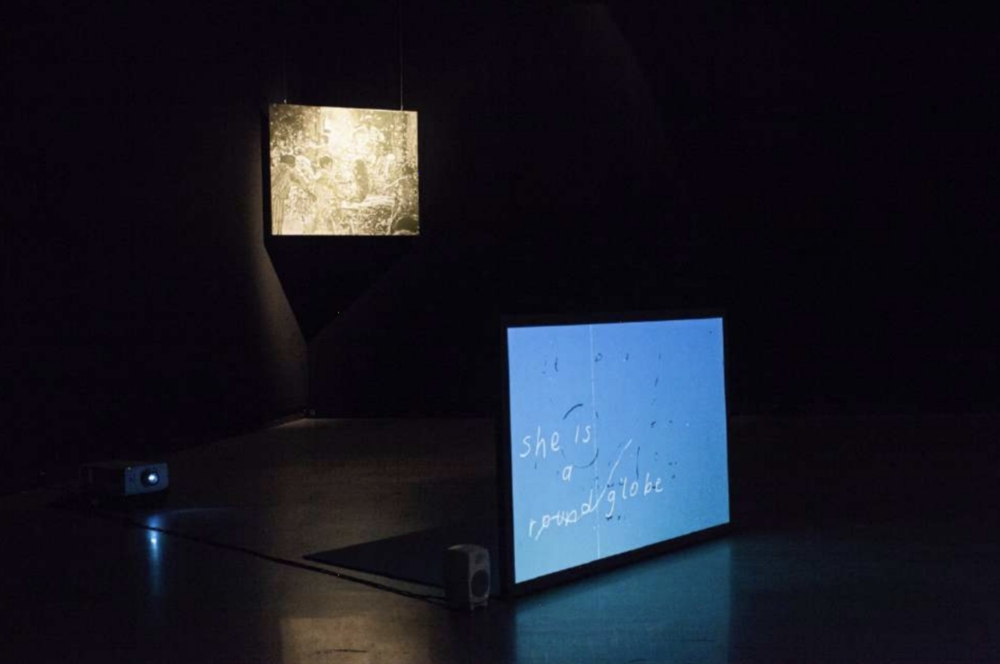

Can you elaborate on your exploration of dreaming, drawing on a concrete example? Let’s focus on your multifaceted project “Dreaming Ruins” (2019), combining poetry, moving images, and installation. How did it start?

It started with my travels in India. I met a ten year old boy called Raja, and we lived together for like two months in a temple. There were many children there who were trained to be monks. He couldn’t speak much English but, I don’t know why, we had a special connection. He didn’t have his mother, no father, and no grandmother or grandfather. This work is dedicated to him. I was trying to show him in this work, what else in this world can be a mother, aside from the body of the mother. I started thinking, what’s mother for me in the world other than my own mother. And then different layers of references started to come together. I was thinking about farmers in Turkey resisting for the land, who are like grandmothers. And then about the film “Paris is Burning” with queer, surrogate families and homes, about the meaning of phrases like being the mother of the house. And I wrote a poem trying to show Raja what mother can be. Another layer in that work was birds. In the video-poem I used a miniature of a bird carrying babies and feeding them. I was exploring and transforming sources of motherhood in the world, which would not be limited to biological kinship, but something everyone could have access to.

It’s such a liberating concept – of extended family and of inhabiting the world. If you don’t mind answering, I would like to ask you a personal question. You`ve lived for many years far away from your biological family, your home, your mother tongue and country. Do you endeavour to create new roots and a sense of home in the realm of art, irrespective of your location, by infusing your work with nourishing and healing myths?

Yes, definitely. When I do my work, I always try to connect with the home and with the mother. I feel an urge to go back there because I’m far away. And also I think about other immigrants.

One of your ways of dealing with alienation and being uprooted seems to be grounded in your collaborative practices, in sharing, caring, in being together. Can you elaborate on the role of relations and cooperation in your work?

My friends, who are very dear to me, often turn into collaborators in time. We share experiences, see the world together, and question it. It’s a way of making a family, especially when you’re far away. For instance, with Alaa Abu Asad, a dear friend and artist from Palestine. Our friendship began at art school with playful exchanges in our languages. We started collecting common words in Arabic and Turkish, which evolved into a book project over the course of a year. Initially, it was just our way of connecting with the world around us and each other. The nature of artistic collaborations start with a need for communication, then evolve in the process of experimentation, and play, using a variety of media.

This reminds me that your work is conceived in a very multifaceted, multimedia, and interdisciplinary way. Can you give some insight into any kinds of patterns, or a particular path that you might follow when you start creating new work?

I wasn’t trained as a maker so I have never worked with any single, fixed medium. I always try to find the proper medium for the idea to be materialized. My working process always starts by diving into a subject or idea. Then the research starts with collecting the hints that cross with my path, from different times, places, people and sources as much as possible. I get lost in it. I follow the tropes, which are somehow aligned with me more than the others. And I eventually make a decision of which aspects I want to take to the surface with me to construct the work on. And I select from the thousands of small motifs, just a handful of them. I try to make sense of these things. I try to relate and connect them.

With the tools or materials that spontaneously come to your mind, is that right?

Yes. I’m still open during this phase. I start writing, drawing, sketching, experimenting with sound or video…

Can you tell us about your working process during the residency in Krzyżowa. How has the place, its surroundings, and residency mode affected you?

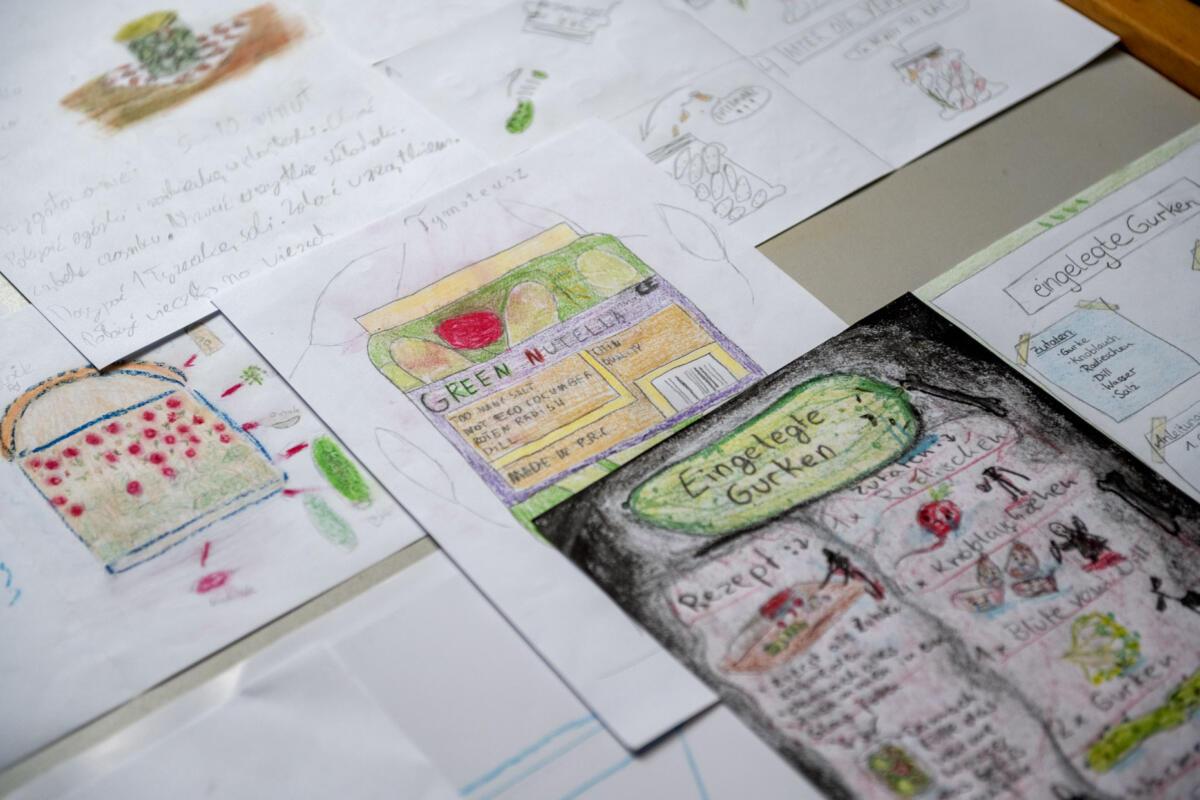

The first thing that I took notice of was the youth and the education programs. Thinking about how to connect with them, my first idea was food. In 2019, I have started a food collective called ‘Eathouse’ together with Vlada Predelina, Merve Kılıçer and Jake Caleb. Social and cultural side of food is always a great inspiration for me. So I decided to make a cookbook together with the youth. We also made a fermentation workshop and a drawing workshop in the permaculture garden, the place I became especially connected with.

Could you tell us more about it?

Agnieszka Duduś, the educator working at the foundation, is trying to use that place as a laboratory for people, for the locals and also for the students. In my workshops, I wanted to give them insight into the garden space from an architectural perspective; to notice the walls, the borders, the limits, the corridors and where the movement is happening, and to pay attention to the overall shape and plan of this garden.

And how did it work?

It worked well. Although they were prone to decorate things, it was hard to make something minimal with just a few elements. It was challenging for them to minimize what they draw and to only focus on space. But I think something shifted in their perception.

You also became interested in other ecological initiatives and farms in the region. We connected with people who are rooted here through food and their ecological practices. As you have learned, locals don’t have strong roots and long family histories here. Due to the exchange of population in Lower Silesia after WWII almost all contemporary inhabitants of the region come from families who had been relocated from other places and cultures.

Yes, I had a feeling that these people are the first generation that are really starting to have a sense of belonging here. But it’s not about national identity, but about being rooted in the land and nature here. I wanted to ask them, why do they do their work, what’s their motivation and their message for the future generations?

So in a way you also contributed to creating an ecological mythology of Lower Silesia.

Yes. I wanted to learn the wisdom these people have and connect to this new place for me through this lesson, to hear what they have to offer. But then I needed more silent time, and started walking in the fields a lot. And the land started to talk to me slowly. I started to connect with the forest nearby, with the river. It was mainly about listening. I think just being in new spaces that you’ve never been in, when you start listening, paying attention to what people are saying, then some things start speaking to you more than the others. And then it turned into the work.

In this residency we don’t put any pressure on artists to produce anything apart from workshops with the youth, but still you created some individual works here. All are very much related to the environment here. Let’s take for example the pieces you made using henna, the material resembling the soil that is here.

From the studio window I could see the fields. So I started to make drawings of the landscape around me, and to think that the landscape could be the connection that we have with the history that’s here. I decided to use pastels and henna.

Tell me about your henna works and the qualities of the material you work with.

I don’t use brushes when I work with henna, I apply it only with my hands. And then in your hand it’s red, but on paper it is a very earthy material. It indeed looks like soil. Its brown colour resonates with the landscape. It’s a living material. When you first apply it, it’s very wet and I like it. It takes three days to dry. Also, henna plays an important role in my culture, I’ve known it from my childhood. It has a dual symbolic nature of celebration and grief. People use henna for weddings, but they also apply it before they kill an animal or before they say goodbye to their son, before he goes to military service.

The visual convention and composition of the piece may evoke associations with a carpet, a form charged with mythological storytelling traditions.

That’s right. I was surprised by the final result and moved that in this work about the Earth, the surface of the Earth turns into this kind of wet carpet.

As a curator of the residency I really appreciate how you connected to the place in so many ways: through the landscape and the history of the land, the permaculture garden, local ecological initiatives and the youth learning here.

It was such a profound experience for me that I get to test every idea, and find support whenever needed. To connect with so many interesting people putting their efforts for this program was the most meaningful part for me.

About the Konrad and Paweł Jarodzki International Artists-in-Residence Programme.

Imprint

| Artist | Ulufer Çelİk |

| Place / venue | The international Konrad and Paweł Jarodzki artist-in-residence programme at the Krzyżowa Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe |

| Dates | 2023 |

| Index | Joanna Sokołowska Konrad Jarodzki Krzyżowa Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe Paweł Jarodzki Ulufer Çelİk |