The motif of a flower bed, or a clover growing on the calf of the protagonist in Karolina Breguła’s film The Offence brings to mind Franz Kafka’s topos of a hidden wound, found in his short story A Country Doctor, among other pieces. The doctor is called to examine an open wound on a boy’s hip; it is bleeding, open and teems with worms. Its cause is unknown and it cannot be healed. Its hideousness is almost beautiful. The doctor is helpless and astonished: “Poor boy, you were past helping. I had discovered your great wound; this blossom in your side was destroying you.”[1] Marta Hekselman points out that the wound is “something almost inherent, difficult to be separated from the self.”[2] It is a recurrent motif in Kafka’s writings; similar wounds are found on the bodies of Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis, of the father in The Judgement, and of Red Peter in A Report to an Academy. The clover bunch on the man’s calf in Breguła’s film may be seen as an allusion to a wound. It is rooted in the man’s body; its remains unknown when it appeared and it cannot be removed. It is invisible to outsiders, but it can be exposed for examination and assessment, or to satisfy curiosity and aesthetic desires. The person afflicted with it acts as though everything were happening independently of him; the clover grows on his body through no fault of his own, like a disease, it is as stigmatising as an anomaly, and it can be described with the words spoken by the boy in A Country Doctor: “A fine wound is all I brought into the world; that was my sole endowment.”[3]

The storyline of The Offence revolves around this obscene phenomenon, the small patch of plants on the skin, the “implant.” In the story, the word “implant” regains its original meaning as a seedling transferred to a different soil, and one that has apparently taken root and given rise to a new plantation. A plant growing on the body stirs imagination; it brings to mind both the borderline state of life as a wound in Kafka’s stories as well as the introduction of the body into the processes of natural circulation: decomposition as the beginning of a new life. The difference is that here things are happening faster than in nature. Instead of growing on a grave, the plant feeds on a living human body. Apparently, this symbiosis of human and clover brings up the question of whose life is dominant in this twosome.

Akin to most Breguła’s films, The Offence has an oneiric structure. In spite of clear similarities to daily life, in spite of places that people well acquainted with Budapest or Warsaw will instantly recognise, the piece has an aura of uncanniness, of reality “shifted one step aside.”

What is interesting is the process of dehumanisation that the owner of the clover wound undergoes. The film depicts his questionable subjectivity: he may have more of subjectivity than a lawn in front of the house because, for instance, he has a certain limited mobility. Bálint Havas, who plays the role of the man afflicted/blessed with the unique trait, fails to utter a single word. He makes sluggish movements, and at a music club he stands motionlessly with his trouser leg up. He is therefore not so much the host of the clover, but in fact he is the clover grown into a human organism, a union of two species. Ovegrown with a plant, he himself seems to be a plant, thus transgressing the border between the human and the non-human – the border that runs across what can be defined as bios. Akin to Kafka’s protagonists, by carrying the plant/wound on his leg he unites beauty and disgust anew. His wound is not a symbolic, but a real flower, a metaphorical representation of an organ or tissue transplant.

Akin to most Breguła’s films, The Offence has an oneiric structure. In spite of clear similarities to daily life, in spite of places that people well acquainted with Budapest or Warsaw will instantly recognise, the piece has an aura of uncanniness, of reality “shifted one step aside.” Narration is fragmented, removed from the constraints of common logic; according to the artist, the film was “made to resemble an exhibition, it is like a tour of a gallery where we see various images.”

It therefore seems hardly significant how the council or the management board of this both fictitious and real city finds out about the peculiar fashion among the inhabitants – growing clover beds on the skin. A meeting is convened and a member of the council even suggests capital punishment, but the mayor or the leader (the political system of the city is unknown) argues against such a radical solution. Persecution and fines are what they finally decide on because – as the representative of the legislative body points out: “We can eradicate it but can’t do anything more. Let’s not forget we want to be a modern society.” Unsurprisingly, illegal planters appear. They move to the underground; they produce seedlings and thus plantation/transplantation of clover is blooming, becoming a source to a secret code. Akin to resistors furtively attached to clothes during the Martial Law in Poland in the 1980s, clover turns into a medium of communication and establishing authentic interpersonal relations in response to the lies of the official propaganda. The decadent atmosphere of the film is charming. It is blindingly obvious that growing clover as a gesture of resistance is as absurd and hilarious as the censorship that is imposed on it. Nothing makes sense here if it is taken literally, but as an allegory the story is very telling. Its meanings are evident. This is a system of power that needs to introduce bans to stay in power. Even a democracy of sorts, which seems to work well on the surface, must be backed by a more or less severe system of repressions. Michel Foucault would call that bio-politics, and the actions taken by the city council – bio-power. He defined bio-power as “the set of mechanisms through which the basic biological features of the human species became the object of a political strategy, of a general strategy of power.”[4]

The prohibition on growing of clover is not different from the ban on abortion or offence to religious feelings, which are part of the legal system in Poland. Polish parliament might as well liberalise the Fetal Protection Act and drop the Penal Code article concerning offending other people’s religious feelings. Nothing would essentially change. The number of newborns would stay the same as today – when the law is restrictive, or, perhaps, it would even increase. The number of acts of religious insult would not grow, since the law has failed to eliminate them so far.Yet, the state would lose control over the female body, which would acquire a symbolic dimension since the patriarchal status quo would be disturbed; as for the question of religious beliefs, the state would deprive itself of a useful instrument of controlling artistic expression.

Breguła introduces a question of stigma, blemish into the context of bio-politics. Clover growing on the human body becomes a brand. Does it become a brand when those in power begin to persecute the clover bearers, or is it the other way round: do they begin to persecute them because the plant is a brand? There is no precise answer. According to Erving Goffman, a stigma is “a special kind of relationship between attribute and stereotype.”[5]

The authorities create their own stereotype in relation to the stigma and use this stereotype in order to maintain their power. Stigma must remain a stigma, or otherwise the authorities would lose their raison d’être. Therefore, the authorities believe that the most dangerous thing that may affect people would be to expose all of them to the “clover effect.” Then, the stigma would cease to stigmatise, and this situation must be prevented. For the stereotype would also lose its power..

Every now and then, the artist abandons the theme of utopia and her critical delight in the ambiguous aesthetics of Modernism. Breguła jumps out of the carousel of mystifications, masks and allegories, which she herself set in motion.

Breguła says that it was not by chance that the film was made at that moment in history. It was produced upon an invitation from the curator Magdalena Ujma and the Workshops of Culture in Lublin. The artist began to work on the film during her stay in Budapest in 2013, where she was pursuing an artistic scholarship. It was a time when the process of transformation of public institutions, initiated a few years before when the right wing Conservative Viktor Orbán had come to power, was in full swing – a process that was to make those institutions directly dependent on the political authorities. For instance, at the Budapest Mücsarnok gallery the liberal director Zsolt Petrányi was replaced by Gábor Gulyás, appointed without a competition and associated with the government circles. The director of the Ludwig Múzeum Barnabás Bencsik stepped down from his position when his five-year contract came to an end. Bencsik took part in the competition for a new director organised by the authorities but failed to secure a nomination; yet the new director Julia Fabényi was nominated in a way that was not considered transparent by the artistic circles in Budapest. In May 2013, an occupation of the Ludwig Múzeum to protest against the governmental policy began. The protest proved futile but, as Breguła claims, a unique aura of community was created as though people had been forced out of lethargy. “That was soon after a discussion broke out in Poland sparked by a suggestion of a few MPs from Lublin about fostering the so-called ‘positive educational climate.’ I was in Budapest at the time, where culture was being increasingly subjected to control. And in both places I could see the shaping of a social movement and some sort of awakening provoked by the impending danger to creative freedom. That was where the idea for The Offence came from,” Breguła explains in an interview for Szum magazine.[6]

Akin to The Tower (2016), Breguła’s film based on the opera written and staged by the artist in Warsaw in 2014, The Offence explores a peculiar sort of power – the power of modernity. The setting of the two films: Modernist estates, corridors, offices and blocks of flats, is a sign and an embodiment of this power. When we buy furniture, wear clothes, decorate our apartment and, perhaps, also when we make a film, we are all drawn into the web of the Modernist stereotype that suggests comfort, minimalism and economy of means. Breguła highlights the motif of Modernist aesthetics in exercising contemporary power. The ban on growing clover may be seen exactly as such a modern restriction. After all, the goal of Modernism was also to achieve order and cleanliness, a a harmonious yet not a very close relationship between humans and nature. “One of the highest delights of the human mind is to perceive the order of nature and to measure its own participation in the scheme of things; the work of art seems to us to be a labor of putting into order, a masterpiece of human order,” wrote Le Corbusier in his Purism manifesto.[7] Therefore, it is not by coincidence that the order to build a sugar tower in The Tower is issued by a person who looks like Le Corbusier. “The time is ripe for construction, not for foolery.”[8] Perhaps too easily decipherable for the viewers, a promise is made in the film that houses will be built of sugar, providing comfortable, warm and quiet living conditions. Seen from this perspective, Modernist architecture in Breguła’s work becomes part of Foucault’s bio-politics. How to oppose it? If we ourselves, the sisters and brothers of Modulor, are its material and tool?

Karolina Breguła, Instruments for Making Noise, 2016

Every now and then, the artist abandons the theme of utopia and her critical delight in the ambiguous aesthetics of Modernism. Breguła jumps out of the carousel of mystifications, masks and allegories, which she herself set in motion. Instruments for Making Noise, shown at the artist’s individual exhibition at the Arsenał Gallery in Białystok in early 2016, is one of such intervals. The rattles and drums,created single-handedly by Breguła from recycled materials found in artists’ studios and art galleries, could be borrowed upon signing a special form. They are meant to be taken to public protests in order to make a lot of noise. Alluringly rough, they remind us of children’s toys. They betray a solid yet home-made quality, as well as bear clear signs of their former functions. Rattles are mounted on brush handles, drums are made of jars for mixing paint. The shouting tube is made of a poster.

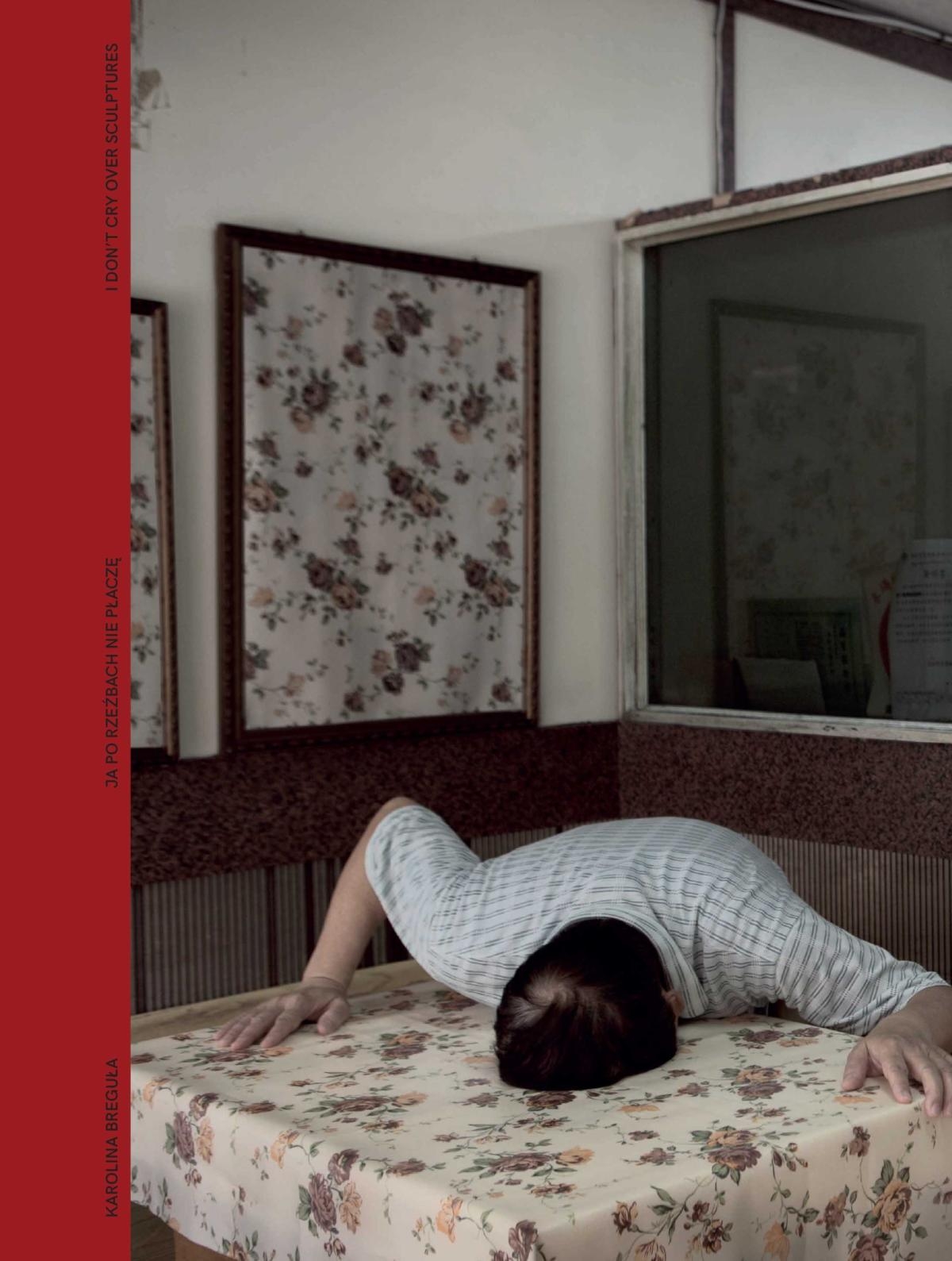

Karolina Breguła. I Don’t Cry Over Sculptures, pub. Fundacja Lokal Sztuki / lokal_30 and Arsenał Gallery in Białystok

Instruments of protest created of instruments of art stand as a deft metaphor for the potential of protest inherent in art itself. It is ironic, or rather mocking. There is no other way to interpret the gesture of distributing a post-artistic and post-aesthetic rattle but as a commentary on the numerous failures of the 20th and 21st century “participation,” perfectly described by Claire Bishop in her book Artificial Hells.[9] However, I would not only see it as a gesture of mockery, but also as a challenge posed to reality. The rattle is and is not a work of art. When used by a big crowd, it becomes something different than at an art show. The artist did not perform her gesture to make it recognisable. What seems more important is the performance of the potential participant of a protest – to take the rattle in your hand, go out on the street and shake it hard.

As I reflect on the links between the works that manifest such varied potentials and directions, for now I am able to find only one answer, certainly inconclusive very vaguely outlined – I would locate the works in the field of post-critical art. This broad and perhaps already overused concept pertains to at least two phenomena: to art that renounces and opposes the political art of the 1990s, as well as to art that adheres to its ideas despite realising the utopian character of its postulates. In other words, either “post-criticism of reaction” or “post-criticism of resistance.”[10] In this light, Breguła’s work would inhabit the latter category.

The text was first published in Karolina Breguła. I Don’t Cry Over Sculptures (pub. Fundacja Lokal Sztuki / lokal_30 and Arsenał Gallery in Białystok

[1] F. Kafka, A Country Doctor, trans. by W. and E. Muir, http://www.101bananas.com/library2/countrydoctor.html (accessed on 28 October 2016).

[2] Cf. M. Hekselman, “Mikrokosmos rany. Granica u Kafki,” Teksty Drugie, 2013, no. 6, p. 263.

[3] F. Kafka, A Country Doctor.

[4] M. Foucault: Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978, trans. by G. Burchell (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), p. 16.

[5] E. Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), p. 4.

[6] “Spojrzenia 2013: Obraz musi działać! Z Karoliną Bregułą rozmawiają Piotr Drewko & Jagna Lewandowska,” Szum, online version, uploaded on 13.09.2013,

http://magazynszum.pl/rozmowy/spojrzenia-2013-obraz-musi-dzialac-rozmowa-z-karolina-bregula (accessed on 30 March 2016).

[7] Le Corbusier, A. Ozenfant, Purism, 1921, https://modernistarchitecture.wordpress.com/2011/08/31/ (accessed on 28 October 2016).

[8] Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, trans. by F. Etchells (New York: Dover, 1986), p. 101.

[9] C. Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London and New York: Verso, 2012).

[10] To paraphrase Hal Foster’s terms applied by him in the 1990s in the discussion on Postmodernism, cf.: H. Foster, “Postmodernism: A Preface,” in Postmodern Culture, ed. H. Foster(London: Pluto Press, 1987), p. XII.

Imprint

| Artist | Karolina Breguła |

| Title | Karolina Breguła. I Don't Cry Over Sculptures |

| Publisher | lokal_30 and Arsenał Gallery in Białystok |

| Published | 2017, Warsaw |

| Website | lokal30.pl |

| Index | Dorota Jarecka Karolina Breguła |